Medical Students and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Attitude and Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

- medical studies form pro-vaccination behaviors;

- depression, anxiety, and stress related to the public debate on vaccination increase the willingness to get vaccinated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measurement Tools

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Sample Size Calculation and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Group

3.2. Experiences with COVID-19 and Related Anxiety

3.3. The Vaccination-Related Experiences

3.4. The DASS-21 Questionnaire Results

3.5. Factors Influencing Pro-Vaccination Attitudes

4. Discussion

4.1. Medical Education Regarding Vaccinology

4.2. Personal Experiences during SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic

4.3. The Current Experience and Anxiety Related to Vaccination

4.4. The Factors Influencing Pro-Vaccination Attitudes

5. Conclusions

6. Strength and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kernéis, S.; Jacquet, C.; Bannay, A.; May, T.; Launay, O.; Verger, P.; Pulcini, C.; Abgueguen, P.; Ansart, S.; Bani-Sadr, F.; et al. Vaccine Education of Medical Students: A Nationwide Cross-sectional Survey. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, e97–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediratta, R.P.; Rizal, R.E.; Xie, J.; Kambhampati, S.; Hills-Evans, K.; Montacute, T.; Zhang, M.; Zaw, C.; He, J.; Sanchez, M.; et al. Galvanizing medical students in the administration of influenza vaccines: The Stanford Flu Crew. Adv. Med. Educ. Pr. 2015, 6, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Riaz, S.; Arif, M.; Daud, S. Immunization in Medical Students: Knowledge and Practice. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 1501–1504. [Google Scholar]

- Collange, F.; Fressard, L.; Pulcini, C.; Sebbah, R.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Verger, P. General practitioners’ attitudes and behaviors toward HPV vaccination: A French national survey. Vaccine 2016, 34, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalkhail, M.S.; Alzahrany, M.S.; Alghamdi, K.A.; Alsoliman, M.A.; Alzahrani, M.A.; Almosned, B.S.; Gosadi, I.M.; Tharkar, S. Uptake of influenza vaccination, awareness and its associated barriers among medical students of a University Hospital in Central Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawislak, D.; Zur-Wyrozumska, K.; Habera, M.; Skrzypiec, K.; Pac, A.; Cebula, G. Evaluation of a Polish Version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21). J. Neurosci. Cogn. Stud. 2020, 4, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoszek, A.; Walkowiak, D.; Bartoszek, A.; Kardas, G. Mental Well-Being (Depression, Loneliness, Insomnia, Daily Life Fatigue) during COVID-19 Related Home-Confinement—A Study from Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power/Sample Size Calculator. Available online: http://www.alz.org/what-is-dementia.asp (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Gabryelska, A.; Szmyd, B.; Szemraj, J.; Stawski, R.; Sochal, M.; Białasiewicz, P. Patients with obstructive sleep apnea present with chronic upregulation of serum HIF-1α protein. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabryelska, A.; Sochal, M.; Turkiewicz, S.; Białasiewicz, P. Relationship between HIF-1 and Circadian Clock Proteins in Obstructive Sleep Apnea Patients—Preliminary Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochal, M.; Małecka-Panas, E.; Gabryelska, A.; Talar-Wojnarowska, R.; Szmyd, B.; Krzywdzińska, M.; Białasiewicz, P. Determinants of Sleep Quality in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esprit, A.; De Mey, W.; Shahi, R.B.; Thielemans, K.; Franceschini, L.; Breckpot, K. Neo-Antigen mRNA Vaccines. Vaccines 2020, 8, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucia, V.C.; Kelekar, A.; Afonso, N.M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J. Public Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barello, S.; Nania, T.; Dellafiore, F.; Graffigna, G.; Caruso, R. ‘Vaccine hesitancy’ among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, G.L.; Muntean, A.-A.; Muntean, M.-M.; Popa, M.I. Knowledge and Attitudes on Vaccination in Southern Romanians: A Cross-Sectional Questionnaire. Vaccines 2020, 8, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, P.; Meurice, F.; Stanberry, L.R.; Glismann, S.; Rosenthal, S.L.; Larson, H.J. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine 2016, 34, 6700–6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarobkiewicz, M.; Zimecka, A.; Zuzak, T.; Cieślak, D.; Roliński, J.; Grywalska, E. Vaccination among Polish university students. Knowledge, beliefs and anti-vaccination attitudes. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2017, 13, 2654–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnquist, C.C.; Sawyer, M.; Calvin, K.; Mason, W.; Blumberg, D.; Luther, J.; Maldonado, Y. Communicating About Vaccines and Vaccine Safety. J. Public Health Manag. Pr. 2013, 19, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haagsma, J.; Tariq, L.; Heederik, D.; Havelaar, A. Infectious disease risks associated with occupational exposure: A systematic review of the literature. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laroche, M.; Pelissier, G.; Noël, S.; Rouveix, E. Occupational and non occupational exposure to viral risk. Rev. Med. Interne 2019, 40, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.M.L.; Salazar, L.M.; Torres, Á.; Arevalo, A.; Franco-Muñoz, C.; Mercado-Reyes, M.M.; Aristizabal, F.A. COVID-19 Infection Detection and Prevention by SARS-CoV-2 Active Antigens: A Synthetic Vaccine Approach. Vaccines 2020, 8, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakker, V.; Jadhav, P.R. Knowledge of hand hygiene in undergraduate medical, dental, and nursing students: A cross-sectional survey. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2015, 4, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Morcillo, A.J.; Moreno-Martínez, F.J.; Susarte, A.M.H.; Hueso-Montoro, C.; Ruzafa–Martínez, M.; Martínez, M.; Martínez, R. Social Determinants of Health, the Family, and Children’s Personal Hygiene: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ograniczenie Prowadzenia Zajęć w Siedzibie Uczelni w Związku z COVID-19—Ministerstwo Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego—Portal Gov.pl. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/nauka/ograniczenie-prowadzenia-zajec-w-siedzibie-uczelni-w-zwiazku-z-covid-19 (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Nechita, F.; Nechita, D. Stress in medical students. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2014, 55, 1263–1266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumar, B.; Shah, M.A.A.; Kumari, R.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, J.; Tahir, A. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Final-year Medical Students. Cureus 2019, 11, e4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoufi, A.; Alsuyihili, A.; Msherghi, A.; Elhadi, A.; Atiyah, H.; Ashini, A.; Ashwieb, A.; Ghula, M.; Ben Hasan, H.; Abudabuos, S.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: Medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding electronic learning. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studenci Zaliczą Zajęcia, Pracując na Rzecz Walki z koronawirusem—Nowelizacja Rozporządzenia ws. Studiów Weszła W Życie—Ministerstwo Edukacji i Nauki—Portal Gov.pl. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/edukacja-i-nauka/studenci-zalicza-zajecia-pracujac-na-rzecz-walki-z-koronawirusem--nowelizacja-rozporzadzenia-ws-studiow-weszla-w-zycie (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Fisher, K.A.; Bloomstone, S.J.; Walder, J.; Crawford, S.; Fouayzi, H.; Mazor, K.M. Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 173, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, B.L.; Felter, E.M.; Chu, K.-H.; Shensa, A.; Hermann, C.; Wolynn, T.; Williams, D.; Primack, B.A. It’s not all about autism: The emerging landscape of anti-vaccination sentiment on Facebook. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2216–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E.; Spina, G.; Tozzi, A.E.; Villani, A. Global Measles Epidemic Risk: Current Perspectives on the Growing Need for Implementing Digital Communication Strategies. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 2819–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanna, I.; Slifka, M.K. Public Fear of Vaccination: Separating Fact from Fiction. Viral Immunol. 2005, 18, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafuri, S.; Gallone, M.S.; Cappelli, M.G.; Martinelli, D.; Prato, R.; Germinario, C. Addressing the anti-vaccination movement and the role of HCWs. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4860–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, N.; Coomes, E.A.; Haghbayan, H.; Gunaratne, K. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: New updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2586–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellens, E.; Bosward, K.L.; Willis, S.; Heller, J.; Cobbold, R.N.; Comeau, J.L.; Norris, J.M.; Dhand, N.K.; Wood, N. Frequency of Adverse Events Following Q Fever Immunisation in Young Adults. Vaccines 2018, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, L.; Newall, A.; Heywood, A.E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Australian medical students towards influenza vaccination. Vaccine 2016, 34, 6193–6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasper, A. Strategies to overcome the public’s fear of vaccinations. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 588–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Choe, Y.J.; Choi, E.H.; Cho, E.H. Sustained Vaccination Coverage during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Epidemic in in the Republic of Korea. Vaccines 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szkopek, P.; Dębowska, M.D. Poziom lęku a postawa wobec obowiązkowych szczepień u kobiet w ciąży. Psychiatria 2020, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkaya, E.; Eker, H.H.; Aycan, N.; Samanci, N. Impact of maternal anxiety level on the childhood vaccination coverage. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2010, 169, 1397–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkiewicz, J.; Michałek, D.; Ryk, A.; Swacha, Z.; Szmyd, B.; Smolewska, E. SLCO1B1 variants as predictors of methotrexate-related toxicity in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkiewicz, J.; Michałek, D.; Ryk, A.; Swacha, Z.; Szmyd, B.; Smolewska, E. The impact of single nucleotide polymorphisms in ADORA2A and ADORA3 genes on the early response to methotrexate and presence of therapy side effects in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Results of a preliminary study. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 23, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, R.; Robles, T.F.; Sheridan, J.; Malarkey, W.B.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Mild Depressive Symptoms Are Associated with Amplified and Prolonged Inflammatory Responses After Influenza Virus Vaccination in Older Adults. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmyd, B.; Rogut, M.; Białasiewicz, P.; Gabryelska, A. The impact of glucocorticoids and statins on sleep quality. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 55, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Medical Students | Non-Medical Students | |

|---|---|---|

| Total; n | 687 | 1284 |

| Male; n (%) | 242 (35.23%) | 728 (56.70%) |

| Median age | 21 (20–24) | 20 (19–22) |

| Population of the place of employment/study; n (% of complete data): | ||

| City > 500,000 residents | 502 (75.83%) | 588 (50.56%) |

| City > 250,000 residents | 69 (10.42%) | 175 (15.05%) |

| City > 100,000 residents | 29 (4.38%) | 143 (12.3%) |

| City > 50,000 residents | 14 (2.12%) | 63 (5.42%) |

| City < 50,000 residents | 23 (3.48%) | 126 (10.83%) |

| Countryside | 25 (3.77%) | 68 (5.84%) |

| Place of residence as a child; n (% of complete data) | ||

| City > 500,000 residents | 145 (21.90%) | 215 (18.49%) |

| City > 250,000 residents | 50 (7.55%) | 87 (7.48%) |

| City > 100,000 residents | 74 (11.18%) | 155 (13.33%) |

| City > 50,000 residents | 72 (10.87%) | 121 (10.4%) |

| City < 50,000 residents | 151 (22.80%) | 296 (25.45%) |

| Countryside | 170 (25.70%) | 289 (24.85%) |

| Medical Students | Non-Medical Students | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection | 59 (8.59%) | 95 (7.39%) | 0.349 (Chi2) |

| Tested for SARS-CoV-2 | 296 (43.1%) | 197 (15.34%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Tested for SARS-CoV-2: | |||

| PCR: | |||

| Nose | 110 (16.01%) | 52 (4.05%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Mouth | 61 (8.88%) | 42 (3.27%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Mouth and nose | 139 (20.23%) | 82 (6.39%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Quick antigen test | 34 (4.95%) | 24 (1.87%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| ELISA | 47 (6.84%) | 24 (1.87%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Family member with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection | 404 (58.81%) | 745 (57.80%) | 0.736 (chi2) |

| Family member deceased in the course of COVID-19: | 47 (6.84%) | 90 (7.00%) | 0.889 (chi2) |

| How often do you visit elderly family members? | |||

| Never | 95 (13.93%) | 213 (16.81%) | 0.096 (chi2) |

| <1×/month | 303 (44.43%) | 443 (34.96%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| 1–2×month | 156 (22.87%) | 312 (24.63%) | 0.388 (chi2) |

| 3–10×/month | 88 (12.9%) | 184 (14.52%) | 0.325 (chi2) |

| >10×/month | 40 (5.87%) | 115 (9.08%) | 0.013 (chi2) |

| Fear of contracting SARS-Cov-2 on a 10-point scale: | |||

| General | 5 (3–6) | 4 (2–6) | <0.001 (UMW) |

| After illness | 4 (3–6) | 3 (2–5) | 0.055 (UMW) |

| Main COVID-19-related concerns | |||

| Health or academic problems | 283 (41.19%) | 341 (26.56%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Health deterioration | 292 (42.50%) | 513 (39.95%) | 0.272 (chi2) |

| Post-COVID syndrome | 369 (53.71%) | 564 (43.93%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Health deterioration in family members | 510 (74.24%) | 809 (63.01%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Social stigma | 32 (4.66%) | 104 (8.10%) | 0.004 (chi2) |

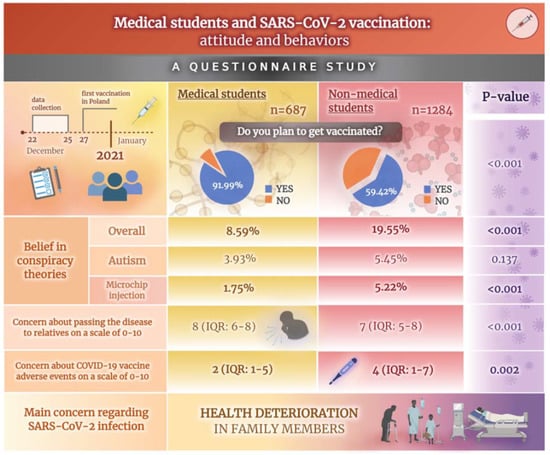

| How concerned are you about passing on the disease to your relatives on a scale of 0–10? | |||

| Overall | 8 (6–8) | 7 (5–8) | <0.001 (UMW) |

| After illness | 8 (6–9) | 7 (4–8) | <0.001 (UMW) |

| Medical Students | Non-Medical Students | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you plan to get vaccinated? | Yes vs. no | ||

| Yes–overall | 632 (91.99%) | 763 (59.42%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| As soon as possible | 524 (76.27%) | 389 (30.3%) | As soon as |

| At some point in the future | 90 (13.1%) | 374 (29.13%) | possible vs. at |

| No | 28 (4.08%) | 279 (21.73%) | some point in the future: |

| I do not know | 27 (3.93%) | 242 (18.85%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| How much are you worried about vaccination side effects on a scale of 0–10? | |||

| overall | 2 (1–5) | 4 (1–7) | <0.001 (UMW) |

| After previous SARS-CoV-2 infection | 2 (1–4) | 5 (1–7) | 0.002 (UMW) |

| What are you most concerned about regarding vaccination? | |||

| Severe hypersensitivity reaction | 66 (9.61%) | 88 (6.85%) | 0.030 (chi2) |

| Fever and malaise | 98 (14.26%) | 176 (13.71%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Swelling and reddening around point of injection | 27 (3.93%) | 71 (5.53%) | 0.112 (chi2) |

| Long-term complications | 273 (39.74%) | 594 (46.26%) | 0.005 (chi2) |

| Conspiracy theories (overall): | 59 (8.59%) | 251 (19.55%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Microchip injection | 12 (1.75%) | 67 (5.22%) | <0.001(Yates) |

| Belief that herd immunity does not exist | 6 (0.87%) | 35 (2.73%) | 0.061 (Yates) |

| Limitation of civil rights | 17 (2.47%) | 150 (11.68%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Control of births by vaccine manufacturers | 5 (0.73%) | 51 (3.97%) | <0.001(Yates) |

| Autism | 27 (3.93%) | 70 (5.45%) | 0.137 (chi2) |

| Have you ever experienced any vaccination side effects? | 146 (21.25%) | 234 (18.22%) | 0.105 (chi2) |

| If so, which one of the following: | |||

| Local reaction | 88 (12.81%) | 63 (4.91%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Fever, malaise | 92 (13.39%) | 133 (10.36%) | 0.436 (chi2) |

| Severe reaction | 14 (2.04%) | 39 (3.04%) | 0.246 (Yates) |

| Long-term side effects | 10 (1.46%) | 46 (3.58%) | 0.007(Yates) |

| I do not remember | 2 (0.29%) | 26 (2.02%) | - (Fisher) |

| Has anyone from your family experienced any side effects of vaccines? | |||

| Local reaction | 88 (12.81%) | 63 (4.91%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Fever, malaise | 92 (13.39%) | 133 (10.36%) | 0.044 (chi2) |

| Severe reaction | 14 (2.04%) | 39 (3.04%) | 0.326 (Yates) |

| Long-term side effects | 10 (1.46%) | 46 (3.58%) | 0.010(Yates) |

| I do not remember | 2 (0.29%) | 26 (2.02%) | - (Fisher) |

| Past medical history of mandatory vaccinations: | Complete vs rest: | ||

| Complete | 665 (96.8%) | 1155 (89.95%) | |

| Incomplete | 19 (2.77%) | 121 (9.42%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| None | 3 (0.44%) | 8 (0.62%) | |

| Past medical history of recommended vaccinations (e.g., influenza one), n (%) | 248 (36.1%) | 354 (27.57%) | <0.001 (chi2) |

| Own children vaccination according to immunization schedule, n (%) | 30 (88.24%) | 51 (77.27%) | 0.145 (Fisher) |

| A. Mental Well-Being According to the DASS-21 Questionnaire | |||

| Medical Students | Non-Medical Students | p-Value | |

| Depression | 6 (3–9) | 6 (3–10) | 0.009 (UMW) |

| Anxiety | 3 (2–6) | 3 (1–6) | 0.035 (UMW) |

| Stress | 7 (4–10) | 6 (4–9) | <0.001 (UMW) |

| B. Binary Logistic Regression Model | |||

| OR | 95%CI | p-Value | |

| Intercept | 0.713 | 0.597–0.850 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 0.945 | 0.920–0.969 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1.006 | 0.968–1.044 | 0.757 |

| Stress | 1.090 | 1.054–1.127 | <0.001 |

| Binary Logistic Regression Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p-Value | |

| Intercept | 1.822 | 0.467–7.099 | 0.387 |

| Family member with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (No) | 0.995 | 0.622–1.589 | 0.984 |

| Family member deceased in the course of COVID-19 (No) | 0.847 | 0.320–2.239 | 0.737 |

| Past medical history of recommended vaccinations (No) | 1.083 | 0.661–1.773 | 0.751 |

| The fear of COVID-19 (0–10) | 1.110 | 0.980–1.256 | 0.101 |

| The fear of passing on the disease to relatives (0–10) | 1.255 | 1.113–1.413 | <0.001 |

| The fear of vaccination side-effects (0–10) | 0.616 | 0.562–0.675 | <0.001 |

| Year of medical study | 1.270 | 1.110–1.451 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 0.930 | 0.867–0.997 | 0.043 |

| Stress | 1.068 | 0.990–1.152 | 0.086 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szmyd, B.; Bartoszek, A.; Karuga, F.F.; Staniecka, K.; Błaszczyk, M.; Radek, M. Medical Students and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Attitude and Behaviors. Vaccines 2021, 9, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020128

Szmyd B, Bartoszek A, Karuga FF, Staniecka K, Błaszczyk M, Radek M. Medical Students and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Attitude and Behaviors. Vaccines. 2021; 9(2):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020128

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzmyd, Bartosz, Adrian Bartoszek, Filip Franciszek Karuga, Katarzyna Staniecka, Maciej Błaszczyk, and Maciej Radek. 2021. "Medical Students and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Attitude and Behaviors" Vaccines 9, no. 2: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020128

APA StyleSzmyd, B., Bartoszek, A., Karuga, F. F., Staniecka, K., Błaszczyk, M., & Radek, M. (2021). Medical Students and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination: Attitude and Behaviors. Vaccines, 9(2), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9020128