COVID-19 and Historic Influenza Vaccinations in the United States: A Comparative Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Outcome Measures

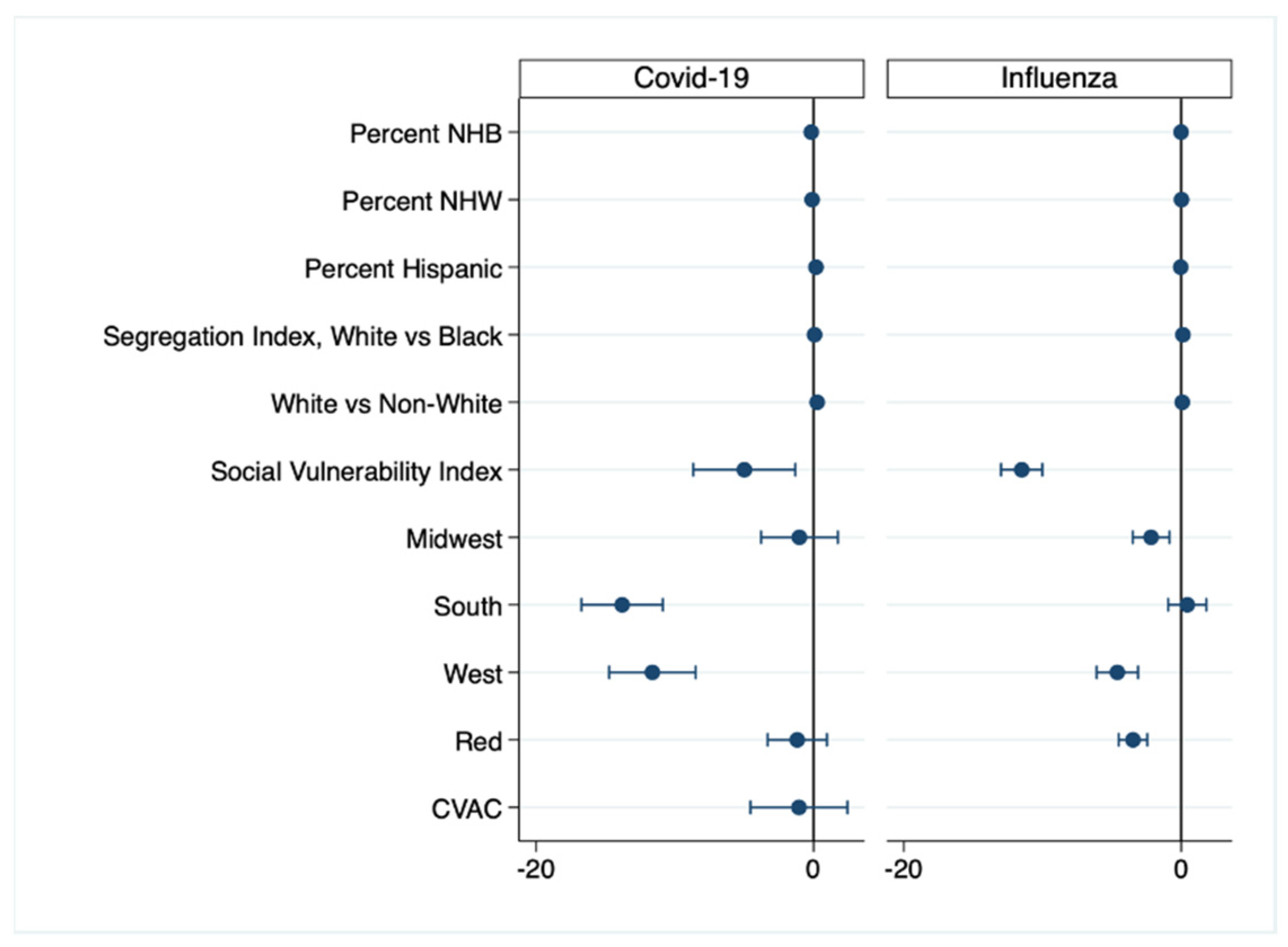

- Race-related variables: Percent of county population belonging to the following races: Nonhispanic White (NHW), Nonhispanic Black (NHB), and Hispanic.

- Median Income: A continuous variable in dollars.

- Vaccine Hesitancy Estimate: Percent of county population who are estimated to be vaccine hesitant. The CDC derived the hesitancy rates by first estimating hesitancy on a Public-Use Microdata Area level using the Census Bureau’s 2019 American Community Survey 1-year Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMA) and then on the granular county level through a PUMA-to-county crosswalk from the Missouri Census Data Center [10]. Vaccine hesitancy is complex and multifaceted; these survey-based estimates are subject to sampling error and nonresponse bias. However, since we use the hesitancy data in conjunction with actual vaccination rates and not to find geographic or temporal trends, the limitations of the dataset are somewhat mitigated.

- Social Vulnerability Index (SVI): The SVI is a multidimensional metric for a community’s ability to respond to adversity (like pandemic illness). It is created from census data and incorporates 15 factors representing socioeconomic status, household composition and disability, minority status and language, and housing type and transportation. An index value of 0 indicates little to no vulnerability, whereas a value of 1 indicates an extremely vulnerable county. The breadth of the measure makes it a uniquely powerful tool for comparison in our study. Several publications describe its use in identifying social vulnerabilities during disasters and have also qualitatively demonstrated its application [11,12].

- COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Index (CVAC): The CVAC is a measure that estimates the level of concern for difficulties in widespread COVID-19 vaccination coverage relating to supply and demand. The modular index is based on five themes including historic undervaccination, sociodemographic barriers, resource-constrained health systems, health accessibility barriers and irregular care-seeking behaviors. These themes are based on indicators such as proportion of individuals without insurance coverage, the proportion of individuals without visits to the doctor for routine checkup and the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries receiving the pneumococcal vaccine. Based on level of concern, the CVAC Index is categorized as follows: Very Low (0.0–0.19), Low (0.20–0.39), Moderate (0.40–0.59), High (0.60–0.79), or Very High (0.80–1.0). Although this measure has not been fully validated yet and there are limitations to its application, by aggregating baseline community characteristics it offers an interesting snapshot into the supply- and demand-related problems that a county might face [13].

- Segregation indices: these indices look at how evenly residents are distributed across a county’s census tracts. We include both the Black vs. White index (segblk) and the non-White vs. White index (segnonwht). The residential segregation index ranges from 0 (complete integration) to 100 (highly segregated).

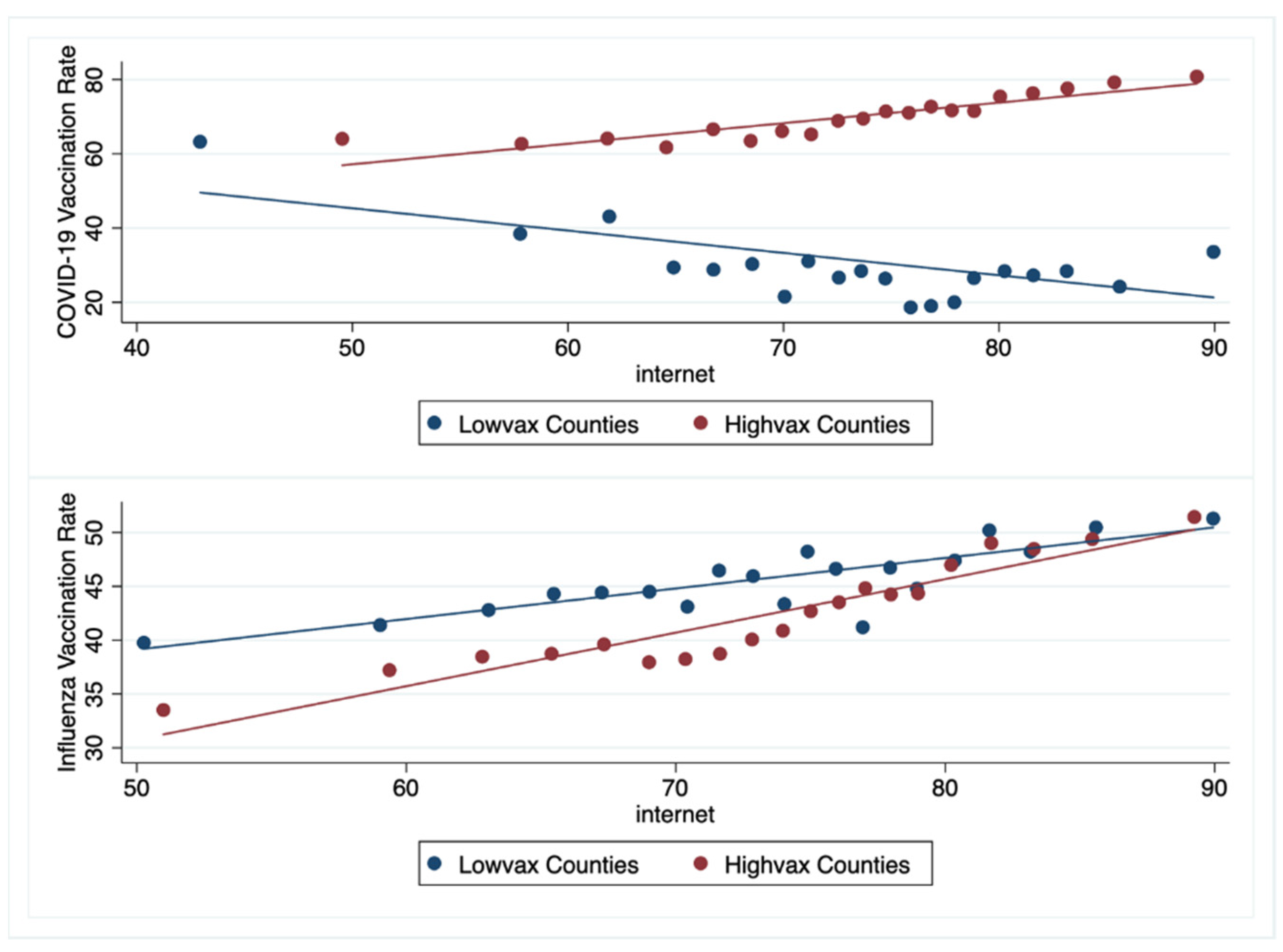

- Internet access: Percent of households in a county with a broadband internet contract.

2.2. Statistical Methods

3. Results

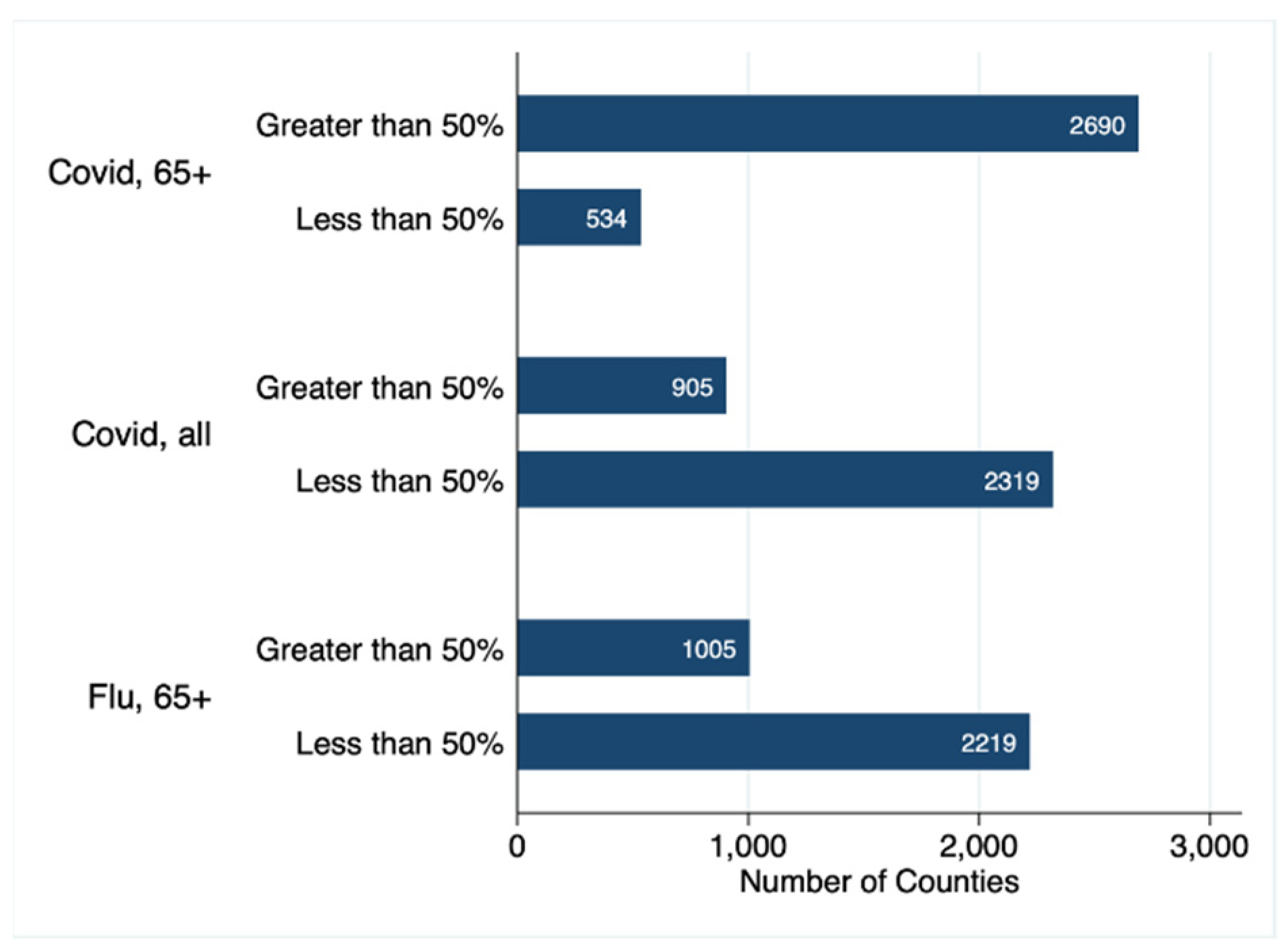

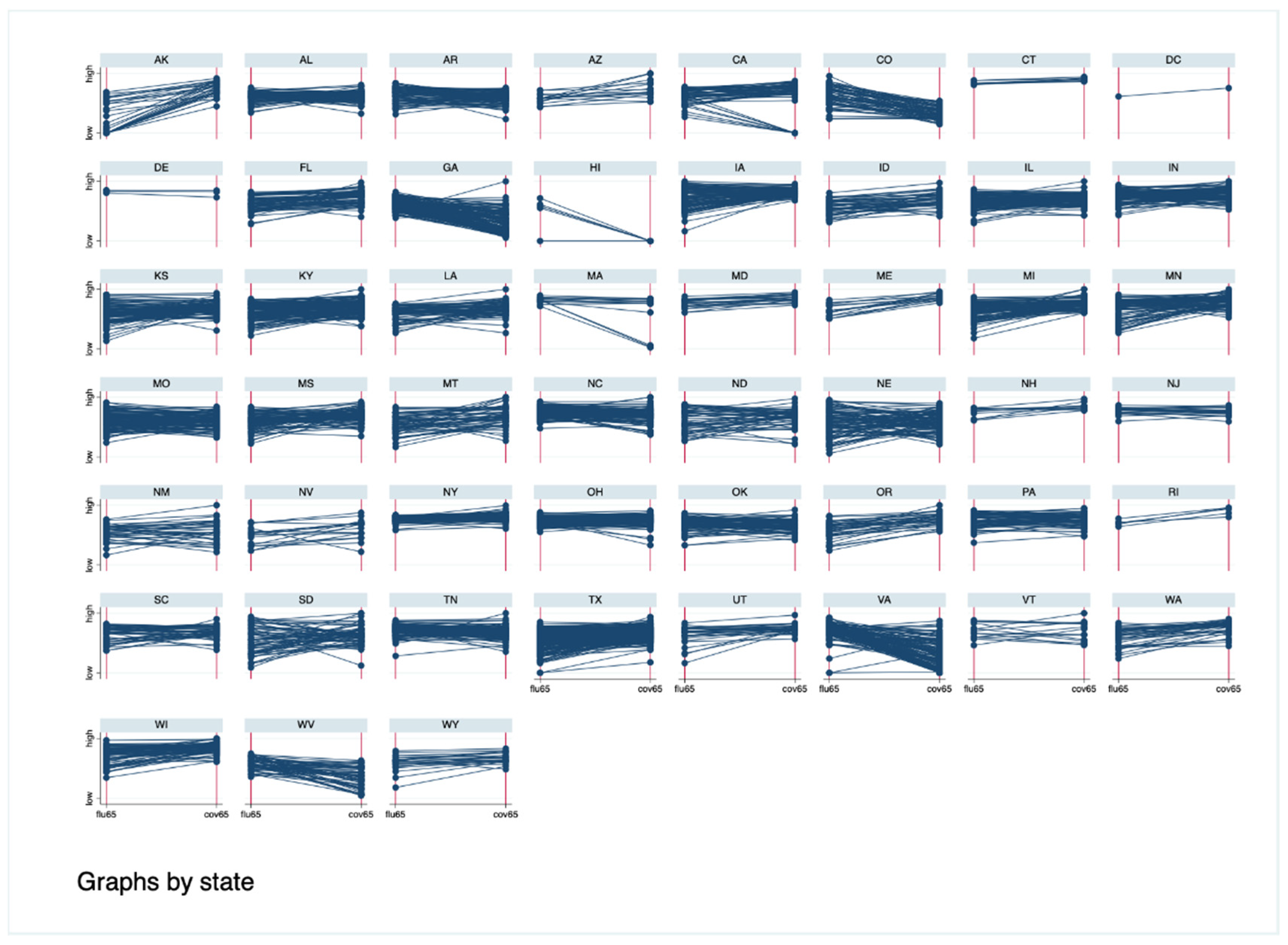

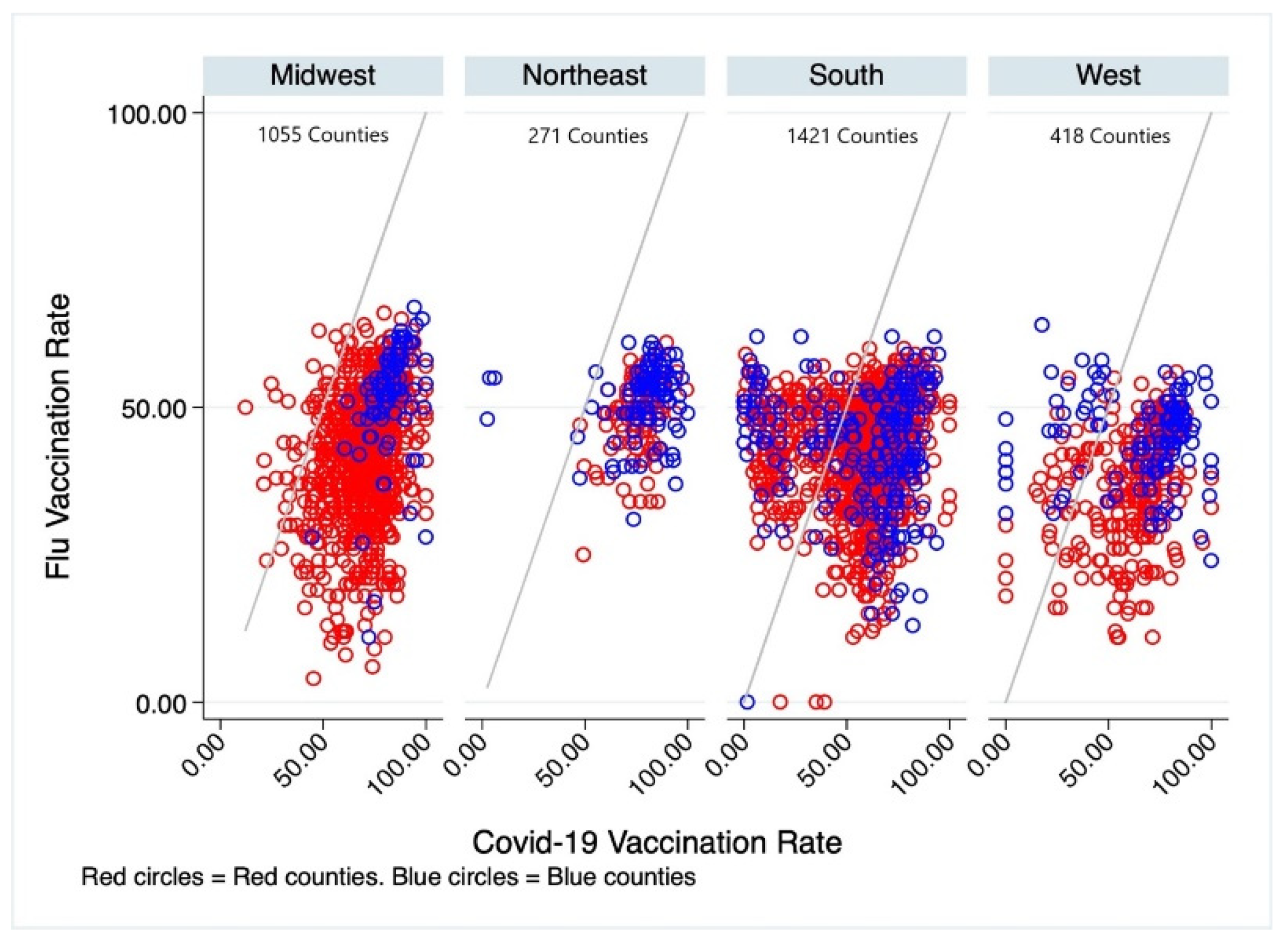

3.1. COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccination Rates

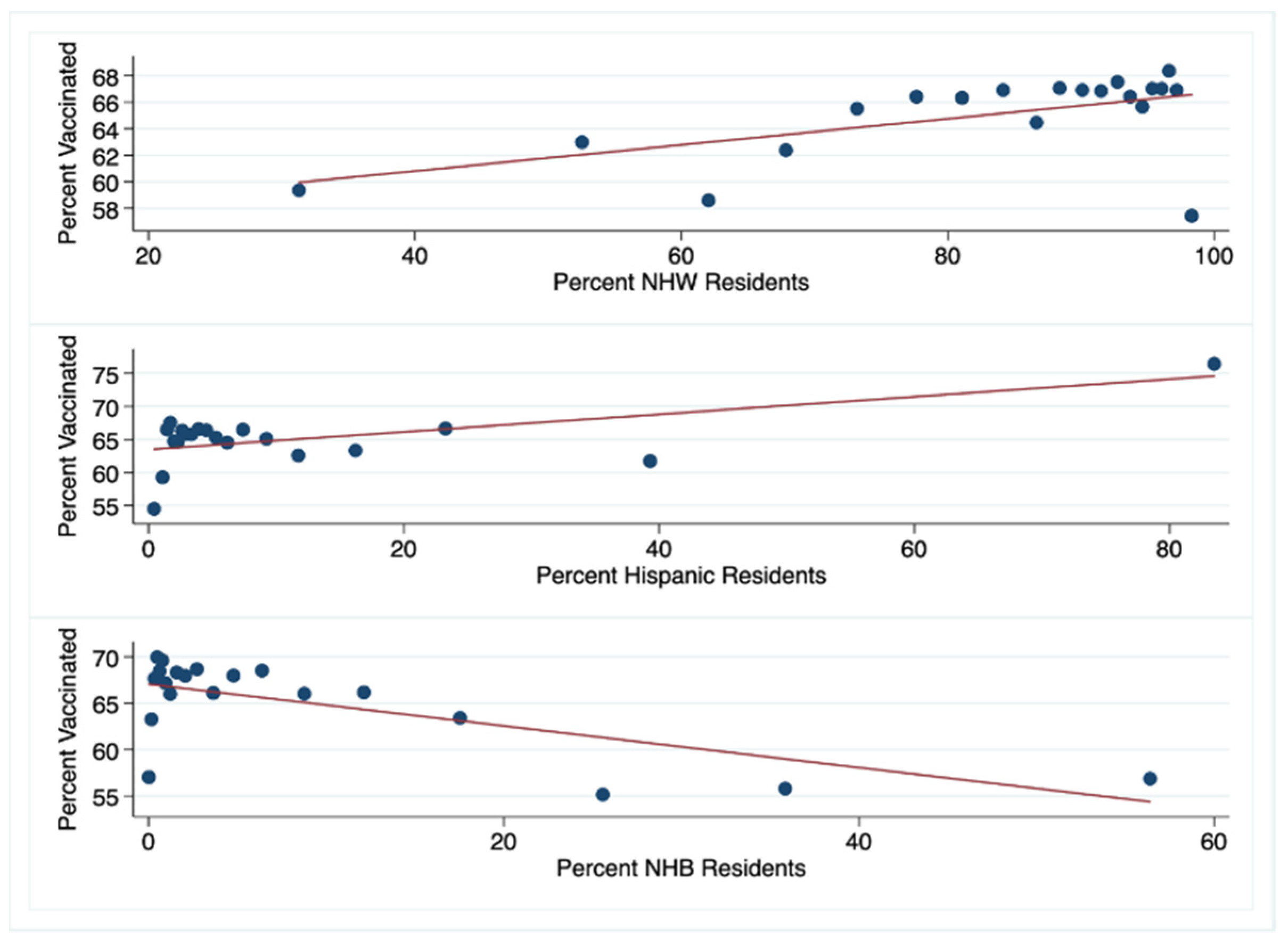

3.2. County-Level Characteristics and Vaccination Rates

3.3. Predictors of COVID-19 and Influenza Vaccination Rates in the 65 Years and Older Population

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Dataset Sources and Noteworthy Limitations

- Obtained From: CDC COVID Data Tracker|Workbook: COVID-19 Vaccine in Texas (Dashboard).

- Source: CDC and Texas Department of Human Health Services.

- Limitations:

- ○

- The COVID-19 Vaccination Rates are in flux as the vaccination effort is still actively underway. This is a preliminary research project aimed at identifying inequitable delivery of the vaccination and at informing interventions designed to decrease vaccine hesitancy.

- ○

- Reporting County-Level COVID-19 Vaccination Data|CDC.

- ▪

- California does not report the county of residence for persons receiving a vaccine when the resident’s county has a population of fewer than 20,000 persons.

- ▪

- Hawaii does not provide CDC with county-of-residence information.

- Obtained From: Vaccine Hesitancy for COVID-19|Data|Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov (accessed on 20 September 2021)).

- Source: CDC.

- Obtained From: Vaccine Hesitancy for COVID-19|Data|Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov (accessed on 20 September 2021)).

- Source: CDC in association with Surgo Surgo Precision For Covid.

- Limitation: All supply and demand related factors are not available at a granular county level consistently across all US counties. Indicators with more than 20% missing data across geographies were not included in the index. Instead, values were imputed with medial values across all counties for county level CVAC.

- Obtained From: CHR&R Program: County Health Rankings & Roadmaps.

- Source: The American Community Survey (ACS) is a nationwide survey designed to provide communities with a fresh look at how they are changing.

- Obtained From: CHR&R Program: County Health Rankings & Roadmaps.

- Source: The US Census Bureau, with support from other federal agencies, created the Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) program to provide more current estimates of selected income and poverty statistics than those from the most recent decennial census.

- Limitation: “Receipts from the following sources are not included as income: capital gains; money received from the sale of property (unless the recipient was engaged in the business of selling such property); the value of income “in kind” from food stamps, public housing subsidies, medical care, employer contributions for individuals, etc.; withdrawal of bank deposits; money borrowed; tax refunds; exchange of money between relatives living in the same household; and gifts and lump-sum inheritances, insurance payments, and other types of lump-sum receipts” [31].

- Obtained From: CDC/ATSDR SVI Data and Documentation Download|Place and Health|ATSDR.

- Source: CDC/Agency for Toxic Diseases and Substances Registry (ATSDR).

- Limitations: Data is from 2018 and may not accurately represent rapidly changing counties. Use of census data only is a limitation as the census counts only where people live, not where they work or play [32].

- Obtained From: CHR&R Program: County Health Rankings & Roadmaps.

- Source: The American Community Survey (ACS) is a nationwide survey designed to provide communities with a fresh look at how they are changing.

- Obtained From: CHR&R Program: County Health Rankings & Roadmaps.

- Source: The American Community Survey (ACS) is a nationwide survey designed to provide communities with a fresh look at how they are changing.

- Limitation: The index was calculated only for counties with a black population greater than 100 persons.

- Obtained From: CHR&R Program: County Health Rankings & Roadmaps.

- Source: The US Census Bureau’s Small Area Health Insurance Estimates (SAHIE) program produces estimates of health insurance coverage for all states and counties. SAHIE (census.gov (accessed on 20 September 2021)).

- Obtained From: CHR&R Program: County Health Rankings & Roadmaps.

- Source: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Office of Minority Health’s Mapping Medicare Disparities (MMD).

- Limitation: This measure includes only the percentage of Medicare FFS enrollees who have received a flu vaccine and may potentially miss trends and disparities among younger age groups or people not enrolled in Medicare.

- Obtained From: GitHub—tonmcg/US_County_Level_Election_Results_08-20: United States General Election Presidential Results by County from 2008 to 2016.

- Source: 2020 election results published by Fox News, Politico and the New York Times.

References

- CDC. COVID Data Tracker. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Lau, H.; Khosrawipour, T.; Kocbach, P.; Ichii, H.; Bania, J.; Khosrawipour, V. Evaluating the Massive Underreporting and Undertesting of COVID-19 Cases in Multiple Global Epicenters. Pulmonology 2021, 27, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.W.; Lu, P.-J.; O’Halloran, A.; Bridges, C.B.; Kim, D.K.; Pilishvili, T.; Hales, C.M.; Markowitz, L.E. Vaccination Coverage Among Adults, Excluding Influenza Vaccination—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, L.A.B.; Gallant, A.J.; Cogan, N.; Rasmussen, S.; Young, D.; Williams, L. Older Adults’ Vaccine Hesitancy: Psychosocial Factors Associated with Influenza, Pneumococcal, and Shingles Vaccine Uptake. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3520–3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.O.; Li, K.-K.; Wei, W.I.; Tang, A.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Lee, S.S. Influenza Vaccine Uptake, COVID-19 Vaccination Intention and Vaccine Hesitancy among Nurses: A Survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 114, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanettini, C.; Omar, M.; Dinalankara, W.; Imada, E.L.; Colantuoni, E.; Parmigiani, G.; Marchionni, L. Influenza Vaccination and COVID19 Mortality in the USA. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilman, L.J. Seasonal Influenza (Flu). Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 54, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.; Gottlieb, L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014, 129, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roozenbeek, J.; Schneider, C.R.; Dryhurst, S.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; van der Linden, S. Susceptibility to Misinformation about COVID-19 around the World. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 201199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleche, T.; Ruhter, J.; Kolbe, A.; Marus, J.; Bush, L.; Sommers, B. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: Demographic Factors, Geographic Patterns, and Changes over Time. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/265341/aspe-ib-vaccine-hesitancy.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Wolkin, A.; Patterson, J.R.; Harris, S.; Soler, E.; Burrer, S.; McGeehin, M.; Greene, S. Reducing Public Health Risk During Disasters: Identifying Social Vulnerabilities. J. Homel Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2015, 12, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flanagan, B.E.; Hallisey, E.J.; Adams, E.; Lavery, A. Measuring Community Vulnerability to Natural and Anthropogenic Hazards: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Social Vulnerability Index. J. Environ. Health 2018, 80, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Surgo Ventures. The U.S. COVID-19 Vaccine Coverage Index (CVAC) Methodology, Version 1. Available online: http://precisionforcovid.org/cvac (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Copper, F.A.; de Vázquez, C.C.; Bell, A.; Mayigane, L.N.; Vedrasco, L.; Chungong, S. Preparing for COVID-19 Vaccine Roll-out through Simulation Exercises. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e742–e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2021, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor Dashboard. KFF. 2021. Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/dashboard/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-dashboard/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Hardeman, A.; Wong, T.; Denson, J.L.; Postelnicu, R.; Rojas, J.C. Evaluation of Health Equity in COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution Plans in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2115653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, V.G.; Huisingh-Scheetz, M.; Arora, V.M. Inequities in Technology Contribute to Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution. JAMA Health Forum 2021, 2, e210264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Rauber, D.; Betsch, C.; Lidolt, G.; Denker, M.-L. Barriers of Influenza Vaccination Intention and Behavior—A Systematic Review of Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy, 2005–2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X. Exploring the Relationship between Political Partisanship and COVID-19 Vaccination Rate. J. Public Health 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahta, L.; Ashkir, A. Addressing MMR Vaccine Resistance in Minnesota’s Somali Community. Minn. Med. 2015, 98, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fridman, A.; Gershon, R.; Gneezy, A. COVID-19 and Vaccine Hesitancy: A Longitudinal Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Health Issues. WHO Will Tackle This Year. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- The Lancet Infectious Diseases. The COVID-19 Infodemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, S.; de Figueiredo, A.; Piatek, S.J.; de Graaf, K.; Larson, H.J. Measuring the Impact of COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation on Vaccination Intent in the UK and USA. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.M.; Osterholm, M.T.; Stauffer, W.M. Critical Considerations for COVID-19 Vaccination of Refugees, Immigrants, and Migrants. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, C.M.; Liebman, A.K.; Galván, A.; Kirsch, J.D.; Stauffer, W.M. Ensuring COVID-19 Vaccines for Migrant and Immigrant Farmworkers. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 1963–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC Cases, Data, and Surveillance. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Hawkins, R.B.; Charles, E.J.; Mehaffey, J.H. Socio-Economic Status and COVID-19-Related Cases and Fatalities. Public Health 2020, 189, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Census Bureau. 2010–2019 County-Level Estimation Details. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/saipe/technical-documentation/methodology/counties-states/county-level.html (accessed on 17 October 2021).

- Flanagan, B.E.; Gregory, E.W.; Hallisey, E.J.; Heitgerd, J.L.; Lewis, B. A Social Vulnerability Index for Disaster Management. J. Homel. Secur. Emerg. Manag. 2011, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Lowvax Counties | Highvax Counties | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3223 | n = 467 | n = 2756 | ||

| COVID-19 Vaccine, eligible ages | 41.10 (33.00–51.50) * | 19.10 (9.70–36.20) | 42.60 (35.60–52.00) | <0.001 |

| COVID-19 Vaccine, 65 and older | 69.37 (57.37–78.20) | 28.50 (13.70–45.20) | 71.20 (62.30–79.10) | <0.001 |

| Influenza Vaccine, 65 and older | 44.00 (37.00–50.00) | 46.00 (41.00–51.00) | 44.00 (36.00–50.00) | <0.001 |

| Percent NHB | 2.37 (0.68–10.27) | 5.72 (1.24–23.75) | 2.04 (0.64–8.50) | <0.001 |

| Percent NHW | 89.24 (75.68–94.96) | 80.49 (64.46–92.45) | 90.26 (78.12–95.21) | <0.001 |

| Percent Hispanic | 4.23 (2.14–10.24) | 5.80 (2.54–18.37) | 4.05 (2.11–9.56) | <0.001 |

| Segregation Index, White vs. Black | 32.37 (0.00–50.29) | 18.06 (0.00–36.52) | 34.84 (0.00–51.74) | <0.001 |

| Segregation Index, White vs. non-White | 27.83 (15.91–37.47) | 18.81 (0.00–30.75) | 29.07 (18.50–38.33) | <0.001 |

| Unemployment | 3.17 (2.40–3.99) | 3.30 (2.43–4.67) | 3.16 (2.39–3.92) | <0.001 |

| High School Completion | 34.42 (29.67–39.15) | 32.90 (28.00–38.38) | 34.62 (29.93–39.28) | <0.001 |

| Median Income (USD) | 49,491 (41,865–57,333) | 43,918 (35,096–55,439) | 50,179.5 (42,835–57,478.5) | <0.001 |

| Uninsured | 9.04 (6.10–12.54) | 9.74 (6.35–13.21) | 8.93 (6.07–12.45) | 0.17 |

| Social Vulnerability Index | 0.5 (0.25–0.75) | 0.49 (0.24–0.8) | 0.5 (0.25–0.74) | 0.85 |

| Internet Access | 74 (68–79) | 70 (61–78) | 75 (69–79) | <0.001 |

| Vaccine Hesitancy | 0.13 (0.098–0.16) | 0.099 (0.068–0.16) | 0.13 (0.1–0.16) | <0.001 |

| CVAC Index | 0.5 (0.25–0.75) | 0.48 (0.25–0.74) | 0.5 (0.25–0.75) | 0.73 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent NHB | −0.262 *** | −0.278 *** | −0.303 *** | −0.171 *** | −0.169 *** |

| Percent NHW | −0.051 | −0.013 | −0.147 *** | −0.106 * | −0.106 ** |

| Percent Hispanic | 0.114 *** | 0.192 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.170 *** | 0.173 *** |

| Segregation Index | |||||

| White vs. Black | 0.041 * | 0.064 *** | 0.070 *** | 0.070 *** | |

| White vs. non-White | 0.304 *** | 0.327 *** | 0.259 *** | 0.257 *** | |

| Social Vulnerability Index | −13.592 *** | −5.609 *** | −4.995 ** | ||

| Region (Index = Northeast) | |||||

| Midwest | −1.161 | −1.022 | |||

| South | −14.025 *** | −13.806 *** | |||

| West | −11.783 *** | −11.624 *** | |||

| Red County (Index = Blue) | −1.283 | −1.179 | |||

| CVAC Index | −1.055 | ||||

| Constant | 70.289 *** | 57.146 *** | 74.423 *** | 76.304 *** | 76.346 *** |

| n | 3224 | 3224 | 3142 | 3111 | 3111 |

| R-squared | 0.0415 | 0.1121 | 0.1372 | 0.2079 | 0.208 |

| aR-squared | 0.0406 | 0.1107 | 0.1355 | 0.2053 | 0.2052 |

| Degrees of Freedom | 3220 | 3218 | 3135 | 3100 | 3099 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent NHB | 0.140 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.173 *** | −0.01 |

| Percent NHW | 0.160 *** | 0.177 *** | 0.119 *** | 0.021 |

| Percent Hispanic | −0.073 *** | −0.074 *** | 0.007 | −0.038 ** |

| Segregation Index | ||||

| White vs. Black | 0.135 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.123 *** | |

| White vs. non-White | 0.075 *** | 0.099 *** | 0.079 *** | |

| Social Vulnerabiliity Index | −11.712 *** | −11.499 *** | ||

| Region (Index = Northeast) | ||||

| Midwest | −2.175 ** | |||

| South | 0.435 | |||

| West | −4.606 *** | |||

| Red Counties (Index = Blue) | −3.478 *** | |||

| Constant | 28.966 *** | 21.785 *** | 30.367 *** | 45.707 *** |

| n | 3142 | 3142 | 3142 | 3111 |

| R-squared | 0.0412 | 0.1948 | 0.2562 | 0.2735 |

| aR-squared | 0.0403 | 0.1936 | 0.2548 | 0.2711 |

| Degrees of Freedom | 3138 | 3136 | 3135 | 3100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mirpuri, P.; Rovin, R.A. COVID-19 and Historic Influenza Vaccinations in the United States: A Comparative Analysis. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111284

Mirpuri P, Rovin RA. COVID-19 and Historic Influenza Vaccinations in the United States: A Comparative Analysis. Vaccines. 2021; 9(11):1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111284

Chicago/Turabian StyleMirpuri, Pranav, and Richard A. Rovin. 2021. "COVID-19 and Historic Influenza Vaccinations in the United States: A Comparative Analysis" Vaccines 9, no. 11: 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111284

APA StyleMirpuri, P., & Rovin, R. A. (2021). COVID-19 and Historic Influenza Vaccinations in the United States: A Comparative Analysis. Vaccines, 9(11), 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9111284