COVID-19 Vaccine and Social Media in the U.S.: Exploring Emotions and Discussions on Twitter

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How did the sentiment of tweets related to the COVID-19 vaccine change between November 2020 and February 2021?

- What are the main topics in tweets related to the COVID-19 vaccine?

- Is there a significant difference between topics in negative and non-negative tweets?

- What are the top topics in negative and non-negative tweets?

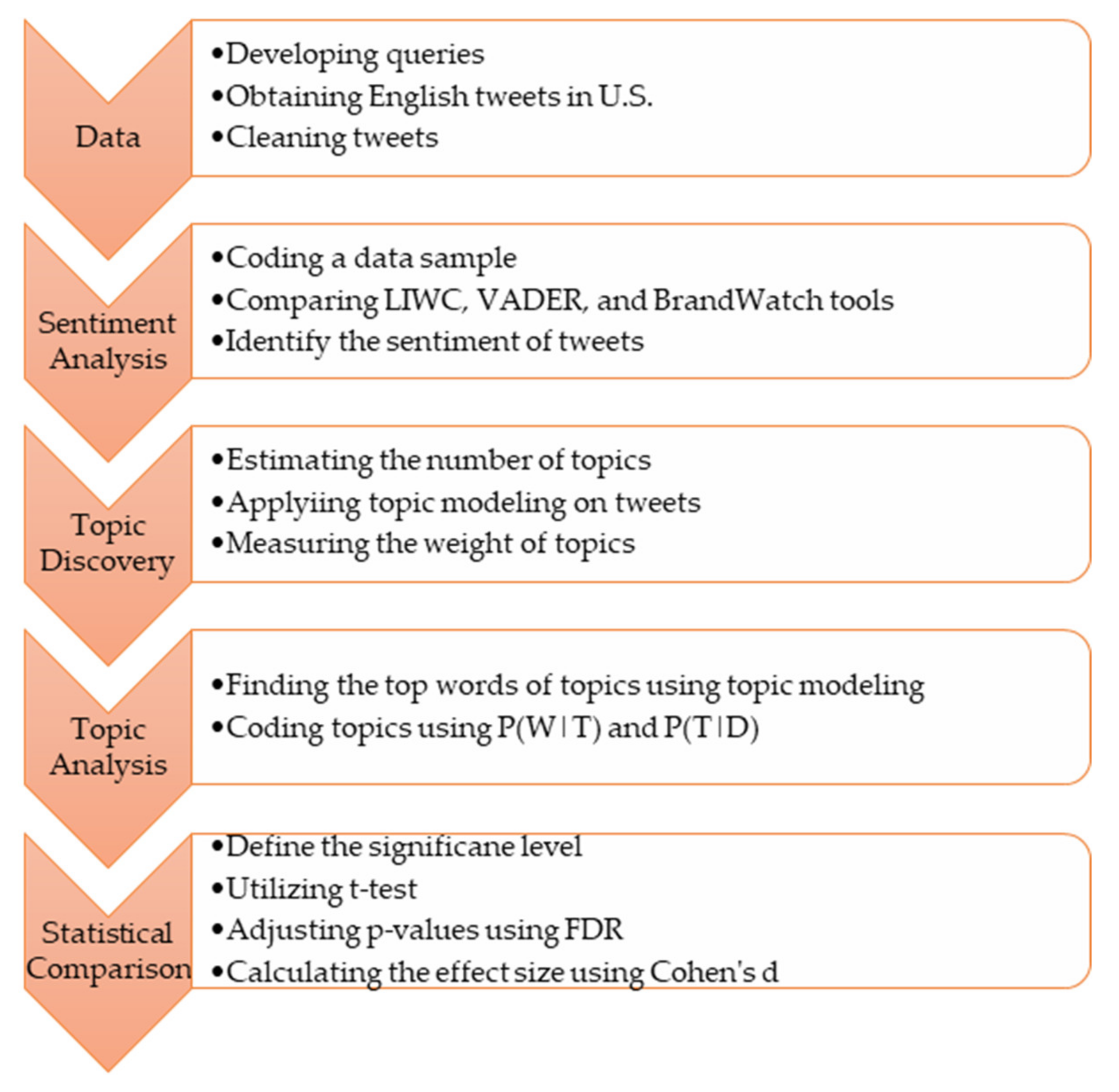

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Sentiment Analysis

2.3. Topic Discovery

| Topics | Documents |

| P(Wi|Tk) | P(Tk|Dj) |

2.4. Topic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Dashboard. 2021. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Samet, A. How the Coronavirus Is Changing US Social Media Usage. In Insider Intelligence. 2020. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/how-coronavirus-changing-us-social-media-usage (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Tweetbinder. How Many Tweets about Covid-19 and Coronavirus? 508 MM Tweets So Far. In Tweet Binder. 2021. Available online: https://www.tweetbinder.com/blog/covid-19-coronavirus-twitter/ (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- McGraw, T. Spending 2020 Together on Twitter. 2020. Available online: https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/topics/insights/2020/spending-2020-together-on-twitter.html (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Rufai, S.R.; Bunce, C. World leaders’ usage of Twitter in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A content analysis. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 510–516. [Google Scholar]

- Asgary, A.; Najafabadi, M.M.; Karsseboom, R.; Wu, J. A drive-through simulation tool for mass vaccination during COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare 2020, 8, 469. [Google Scholar]

- Asgary, A.; Valtchev, S.Z.; Chen, M.; Najafabadi, M.M.; Wu, J. Artificial Intelligence Model of Drive-Through Vaccination Simulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 268. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Lundy, M.; Webb, F.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Twitter and research: A systematic literature review through text mining. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 67698–67717. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Lundy, M.; Webb, F.; Boyajieff, H.R.; Zhu, M.; Lee, D. Automatic Categorization of LGBT User Profiles on Twitter with Machine Learning. Electronics 2021, 10, 1822. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, M.J.; Dredze, M. Social monitoring for public health. In Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, C.; Eysenbach, G. Pandemics in the age of Twitter: Content analysis of Tweets during the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14118. [Google Scholar]

- Moorhead, S.A.; Hazlett, D.E.; Harrison, L.; Carroll, J.K.; Irwin, A.; Hoving, C. A new dimension of health care: Systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e1933. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.K.; Hawkins, J.B.; Nguyen, L.; Nsoesie, E.O.; Tuli, G.; Mansour, R.; Brownstein, J.S. Research brief report: Using twitter to identify and respond to food poisoning: The food safety stl project. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2017, 23, 577. [Google Scholar]

- Scanfeld, D.; Scanfeld, V.; Larson, E.L. Dissemination of health information through social networks: Twitter and antibiotics. Am. J. Infect. Control 2010, 38, 182–188. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Lundy, M.; Webb, F.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; McKeever, B.W.; McKeever, R. Identifying and Analyzing Health-Related Themes in Disinformation Shared by Conservative and Liberal Russian Trolls on Twitter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2159. [Google Scholar]

- Salathé, M.; Khandelwal, S. Assessing vaccination sentiments with online social media: Implications for infectious disease dynamics and control. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002199. [Google Scholar]

- Corley, C.D.; Cook, D.J.; Mikler, A.R.; Singh, K.P. Text and structural data mining of influenza mentions in web and social media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 596–615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Li, Z.; Yu, Z.; He, J.; Zhou, J. Communication related health crisis on social media: A case of COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Yu, X.; Xu, H. Chinese public’s attention to the COVID-19 epidemic on social media: Observational descriptive study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Alhuwail, D.; Househ, M.; Hamdi, M.; Shah, Z. Top concerns of Tweeters during the COVID-19 pandemic: Infoveillance study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19016. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Chen, J.; Hu, R.; Chen, C.; Zheng, C.; Su, Y.; Zhy, T. Twitter Discussions and Emotions About the COVID-19 Pandemic: Machine Learning Approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e20550. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Anderson, M. Social media and COVID-19: Characterizing anti-quarantine comments on Twitter. Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, e349. [Google Scholar]

- Shahi, G.K.; Dirkson, A.; Majchrzak, T.A. An exploratory study of covid-19 misinformation on twitter. Online Soc. Netw. Media 2021, 22, 100104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.; Karami, A.; Bozorgi, P. Social media and COVID-19: Can social distancing be quantified without measuring human movements? Proc. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, e378. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.M.; Vegvari, C.; Truscott, J.; Collyer, B.S. Challenges in creating herd immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection by mass vaccination. Lancet 2020, 396, 1614–1616. [Google Scholar]

- Moehring, A.; Collis, A.; Garimella, K.; Rahimian, M.A.; Aral, S.; Eckles, D. Surfacing Norms to Increase Vaccine Acceptance. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3782082 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, J.; Featherstone, J.D.; Barnett, G.A. Identifying Vaccine Hesitant Communities on Twitter and their Geolocations: A Network Approach. In Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2021; p. 3964. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Dredze, M. Vaccine images on twitter: Analysis of what images are shared. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e130. [Google Scholar]

- Broniatowski, D.A.; Jamison, A.M.; Qi, S.; AlKulaib, L.; Chen, T.; Benton, A.; Quinn, S.C.; Drezde, M. Weaponized health communication: Twitter bots and Russian trolls amplify the vaccine debate. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Piedrahita-Valdés, H.; Piedrahita-Castillo, D.; Bermejo-Higuera, J.; Guillem-Saiz, P.; Bermejo-Higuera, J.R.; Guillem-Saiz, J.; Sicilia-Montalvo, J.A.; Machio-Redígor, F. Vaccine Hesitancy on Social Media: Sentiment Analysis from June 2011 to April 2019. Vaccines 2021, 9, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, P.M.; Leader, A.; Yom-Tov, E.; Budenz, A.; Fisher, K.; Klassen, A.C. Applying multiple data collection tools to quantify human papillomavirus vaccine communication on Twitter. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Griffith, J.; Marani, H.; Monkman, H. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Canada: Content Analysis of Tweets Using the Theoretical Domains Framework. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26874. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eibensteiner, F.; Ritschl, V.; Nawaz, F.A.; Fazel, S.S.; Tsagkaris, C.; Kulnik, S.T.; Crutzen, R.; Klager, E.; Völkl-Kernstock, S.; Schaden, E.; et al. People’s Willingness to Vaccinate Against COVID-19 Despite Their Safety Concerns: Twitter Poll Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28973. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwok, S.W.H.; Vadde, S.K.; Wang, G. Tweet Topics and Sentiments Relating to COVID-19 Vaccination Among Australian Twitter Users: Machine Learning Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hussain, A.; Tahir, A.; Hussain, Z.; Sheikh, Z.; Gogate, M.; Dashtipour, K.; Ali, A.; Sheikh, A. Artificial Intelligence–Enabled Analysis of Public Attitudes on Facebook and Twitter Toward COVID-19 Vaccines in the United Kingdom and the United States: Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26627. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Liu, S. Understanding Behavioral Intentions Toward COVID-19 Vaccines: A Theory-based Content Analysis of Tweets. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28118. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, R.G.; Hagen, L.; Walker, K.; O’Leary, H.; Lengacher, C. The COVID-19 vaccine social media infodemic: Healthcare providers’ missed dose in addressing misinformation and vaccine hesitancy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Atehortua, N.A.; Patino, S. COVID-19, a tale of two pandemics: Novel coronavirus and fake news messaging. Health Promot. Int. 2021, 36, 524–534. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Peco, I.; Jiménez-Gómez, B.; Peña Deudero, J.J.; Benitez De Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Núñez, C. Healthcare Professionals’ Role in Social Media Public Health Campaigns: Analysis of Spanish Pro Vaccination Campaign on Twitter. Healthcare 2021, 9, 662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- To, Q.G.; To, K.G.; Huynh, V.-A.N.; Nguyen, N.T.; Ngo, D.T.; Alley, S.J.; Tran, A.N.Q.; Tran, A.N.P.; Pham, N.T.T.; Bui, T.X.; et al. Applying Machine Learning to Identify Anti-Vaccination Tweets during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Criss, S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Norton, S.; Virani, I.; Titherington, E.; Tillmanns, E.L.; Kinnae, C.; Maiolo, G.; Kirby, A.B.; Gee, G.C. Advocacy, Hesitancy, and Equity: Exploring US Race-Related Discussions of the COVID-19 Vaccine on Twitter. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Boyd, R.L.; Jordan, K.; Blackburn, K. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC2015; Pennebaker Conglomerates: Austin, TX, USA, 2015; Available online: www.LIWC.net (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. Vader: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bannister, K. Understanding Sentiment Analysis: What It Is & Why It’s Used. In Brandwatch [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/understanding-sentiment-analysis/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Zhou, B.; Kharrazi, H. FLATM: A Fuzzy Logic Approach Topic Model for Medical Documents. In Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Meeting of the North American Fuzzy Information Processing Society (NAFIPS), Redmond, WA, USA, 17–19 August 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jungherr, A. Twitter use in election campaigns: A systematic literature review. J. Inf. Technol. Politics 2016, 13, 72–91. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, A.; Bookstaver, B.; Nolan, M.; Bozorgi, P. Investigating Diseases and Chemicals in COVID-19 Literature with Text Mining. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2021, 1, 100016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Dahl, A.A.; Shaw, G.; Valappil, S.P.; Turner-McGrievy, G.; Kharrazi, H.; Bozorgi, P. Analysis of Social Media Discussions on (#)Diet by Blue, Red, and Swing States in the U.S. Healthcare 2021, 9, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, A.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Zhou, B.; Kharrazi, H. Fuzzy approach topic discovery in health and medical corpora. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 20, 1334–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Rehurek, R.; Sojka, P. Software framework for topic modelling with large corpora. In Proceedings of the LREC 2010 Workshop on New Challenges for NLP Frameworks, Valleta, Malta, 22 May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Röder, M.; Both, A.; Hinneburg, A. Exploring the space of topic coherence measures. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Shanghai, China, 2–6 February 2015; pp. 399–408. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, A.K. Mallet: A Machine Learning for Language Toolkit. 2002. Available online: http://mallet.cs.umass.edu/ (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Lim, B.H.; Valdez, C.E.; Lilly, M.M. Making meaning out of interpersonal victimization: The narratives of IPV survivors. Violence Against Women 2015, 21, 1065–1086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pruim, R.; Kaplan, D.; Horton, N. Mosaic: Project MOSAIC Statistics and Mathematics Teaching Utilities. R Package Version 06-2. 2012. Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=mosaic (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Kim, J.H.; Ji, P.I. Significance testing in empirical finance: A critical review and assessment. J. Empir. Financ. 2015, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Good, I.J. C140. Standardized tail-area prosabilities. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 1982, 16, 65–66. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using effect size—Or why the P value is not enough. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2012, 4, 279. [Google Scholar]

- Sawilowsky, S.S. New effect size rules of thumb. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2009, 8, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, A.C.; Slavin, R.E. How methodological features affect effect sizes in education. Educ. Res. 2016, 45, 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Funk, C.; Tyson, A. Growing Share of Americans Say They Plan To Get a COVID-19 Vaccine—Or Already Have. In Pew Research Center Science & Society. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/03/05/growing-share-of-americans-say-they-plan-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-or-already-have/ (accessed on 6 May 2021).

- Thelwall, M.; Kousha, K.; Thelwall, S. Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy on English-language Twitter. Prof. Inf. EPI 2021, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, J. Over 1 Billion Worldwide Unwilling to Take COVID-19 Vaccine. In Gallup.com. 2021. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/348719/billion-unwilling-covid-vaccine.aspx (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Hughes, A.; Wojcik, S. 10 Facts about Americans and Twitter; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Han, B.; Zhao, T.; Liu, H.; Liu, B.; Chen, L.; Xie, M.; Liu, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, S.; et al. Vaccination willingness, vaccine hesitancy, and estimated coverage at the first round of COVID-19 vaccination in China: A national cross-sectional study. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2833–2842. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Label | Short Description | Topic |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Vaccine Exemption Bill | COVID-19 Vaccine Exemption Bill | vaccine gates people bill COVID government trust control chip forced |

| T2 | Vaccine Distribution | COVID-19 Vaccine Distribution | distribution vaccine rollout state vaccination plan COVID governor gov federal |

| T3 | Death and Vaccine | COVID-19 Death and Vaccine | COVID vaccine coronavirus news health deaths doctor cases reaction |

| T4 | Vaccine Information Sharing | COVID-19 Vaccine Information Sharing | vaccine COVID black questions information women community read vaccination vaccines public |

| T5 | Politician Hoax | Politician Hoax on COVID-19 Vaccine | vaccine line people COVID white house wait front ill hoax |

| T6 | Vaccination Sites | COVID-19 Vaccination Sites | vaccination county COVID appointments health sites mass state week clinic |

| T7 | Vaccination Hesitancy | COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy | vaccine people make good sense thing point understand bad science |

| T8 | Emergency Approval of Vaccines | Emergency Approval of COVID-19 Vaccines | vaccine COVID johnson fda emergency pfizer distribution approval panel moderna |

| T9 | Vaccines’ Mechanism | COVID-19 Vaccines’ Mechanism | vaccine flu virus immune COVID system mrna body response antibodies |

| T10 | Vaccine for Teachers | COVID-19 Vaccine for Teachers | vaccine teachers people school risk vaccination high COVID priority group |

| T11 | Vaccination, Mask, and Social Distancing | COVID-19 Vaccine, Mask, and Social Distancing | vaccine mask wear people stay social safe work virus distancing |

| T12 | Vaccine Immunity | COVID-19 Vaccine Immunity | vaccine virus immunity people rate herd COVID spread death effective |

| T13 | Vaccine Effectiveness | COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness | vaccine COVID pfizer effective trial data moderna test results study |

| T14 | Friends and Family Vaccination | COVID-19 Vaccination Stories of Friends and Family | vaccine COVID year family told friends mom expect wait friend |

| T15 | Vaccination and Election | COVID-19 Vaccination and Election | vaccine trump speed election plan COVID virus promised biden healthcare |

| T16 | Trump Administration Performance | Performance of Trump Administration and COVID-19 Vaccine | vaccine people lives trump americans pandemic country virus thousands dead |

| T17 | Vaccine Development Timeline | COVID-19 Vaccine Development Timeline | vaccine time months years weeks long takes work make fast |

| T18 | Vaccination for Health Workers and Nursing Home Residents | COVID-19 Vaccine for Health Workers and Nursing Home Residents | vaccine workers COVID healthcare essential nursing home residents staff hospital |

| T19 | Vaccine Management | Management of COVID-19 Vaccines | vaccine doses million COVID people week states supply shots administration |

| T20 | Travel Mandatory Testing and Vaccine | Mandatory COVID-19 Testing and Vaccine for Travel | vaccine COVID mandatory travel make proof order testing require law |

| T21 | Getting Vaccines Stories | Stories of Getting COVID-19 Vaccines | vaccine COVID today dose good shot received day tomorrow week |

| T22 | Vaccination Impact on Market | Impact of COVID-19 Vaccination on Market | vaccine end back COVID news year normal pandemic bring market |

| T23 | Biden vs. Trump on Vaccine | Biden vs. Trump on COVID-19 Vaccine | trump vaccine biden president credit administration distribution plan office team |

| T24 | Unrelated (Sport) | Unrelated (Sport) | vaccine game time watch back show play live dolly COVID |

| T25 | Supporting Pharmaceutical Companies | Supporting Pharmaceutical Companies for COVID-19 Vaccine Production | vaccine government COVID companies big pay make pharma funding research |

| T26 | Vaccine Side Effects | COVID-19 Vaccine Side Effects | vaccine side COVID effects shot long arm feel dose days |

| ID | Topic | t-Test Result | Cohen’s d Mean | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | Vaccine Exemption Bill | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T2 | Vaccine Distribution | NS | NS | NS |

| T3 | Death and Vaccine | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T4 | Vaccine Information Sharing | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.6 | Large |

| T5 | Politician Hoax | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.3 | Small |

| T6 | Vaccination Sites | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.3 | Medium |

| T7 | Vaccination Hesitancy | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T8 | Emergency Approval of Vaccines | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T9 | Vaccines’ Mechanism | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T10 | Vaccine for Teachers | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.1 | Very Small |

| T11 | Vaccination, Mask, and Social Distancing | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.3 | Medium |

| T12 | Vaccine Immunity | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T13 | Vaccine Effectiveness | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.3 | Medium |

| T14 | Friends and Family Vaccination | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T15 | Vaccination and Election | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T16 | Trump Administration Performance | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.4 | Medium |

| T17 | Vaccine Development Timeline | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T18 | Vaccination for Health Workers and Nursing Home Residents | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.1 | Very Small |

| T19 | Vaccine Management | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T20 | Travel Mandatory Testing and Vaccine | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.2 | Small |

| T21 | Getting Vaccines Stories | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.3 | Small |

| T22 | Vaccination Impact on Market | * Neg < NonNeg | 0.1 | Very Small |

| T23 | Biden vs. Trump on Vaccine | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.1 | Very Small |

| T25 | Supporting Pharmaceutical Companies | NS | NS | NS |

| T26 | Vaccine Side Effects | * Neg > NonNeg | 0.1 | Very Small |

| Negative Tweets | Non-Negative Tweets |

|---|---|

| Trump Administration Performance | Vaccination Sites |

| Vaccination Hesitancy | Stories of Getting Vaccines |

| Vaccine Immunity | Vaccine Effectiveness |

| Vaccination, Mask, and Social Distancing | Vaccine Information |

| Biden vs. Trump on Vaccine | Vaccine Management |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karami, A.; Zhu, M.; Goldschmidt, B.; Boyajieff, H.R.; Najafabadi, M.M. COVID-19 Vaccine and Social Media in the U.S.: Exploring Emotions and Discussions on Twitter. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101059

Karami A, Zhu M, Goldschmidt B, Boyajieff HR, Najafabadi MM. COVID-19 Vaccine and Social Media in the U.S.: Exploring Emotions and Discussions on Twitter. Vaccines. 2021; 9(10):1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101059

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarami, Amir, Michael Zhu, Bailey Goldschmidt, Hannah R. Boyajieff, and Mahdi M. Najafabadi. 2021. "COVID-19 Vaccine and Social Media in the U.S.: Exploring Emotions and Discussions on Twitter" Vaccines 9, no. 10: 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101059

APA StyleKarami, A., Zhu, M., Goldschmidt, B., Boyajieff, H. R., & Najafabadi, M. M. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccine and Social Media in the U.S.: Exploring Emotions and Discussions on Twitter. Vaccines, 9(10), 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9101059