An Overview of the Factors Related to Leishmania Vaccine Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

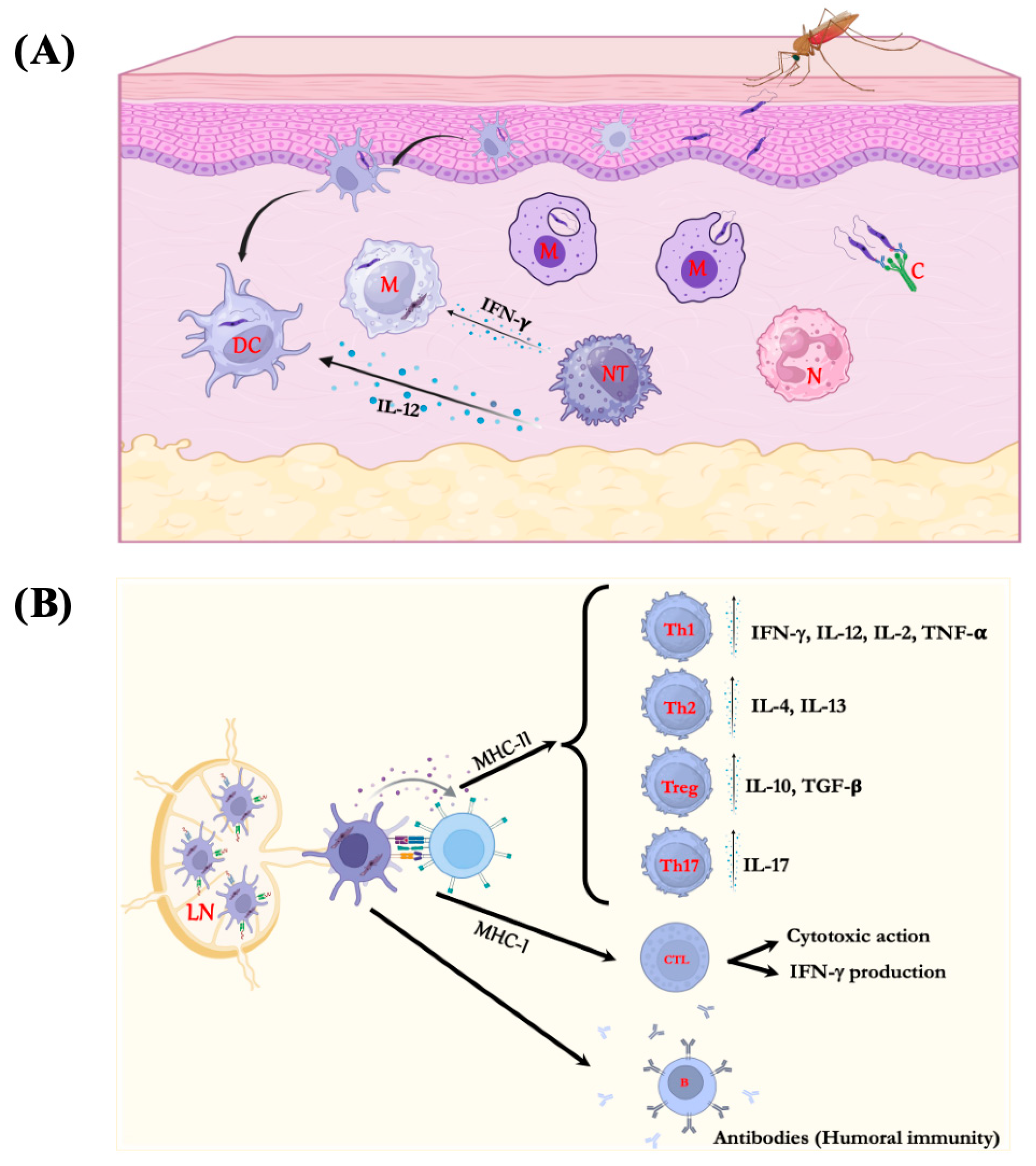

2. Immune Response in Leishmaniasis

3. Experimental Models

3.1. Experimental Models in Visceral Leishmaniasis

3.2. Experimental Models in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

4. Adjuvants

4.1. Description of Adjuvants

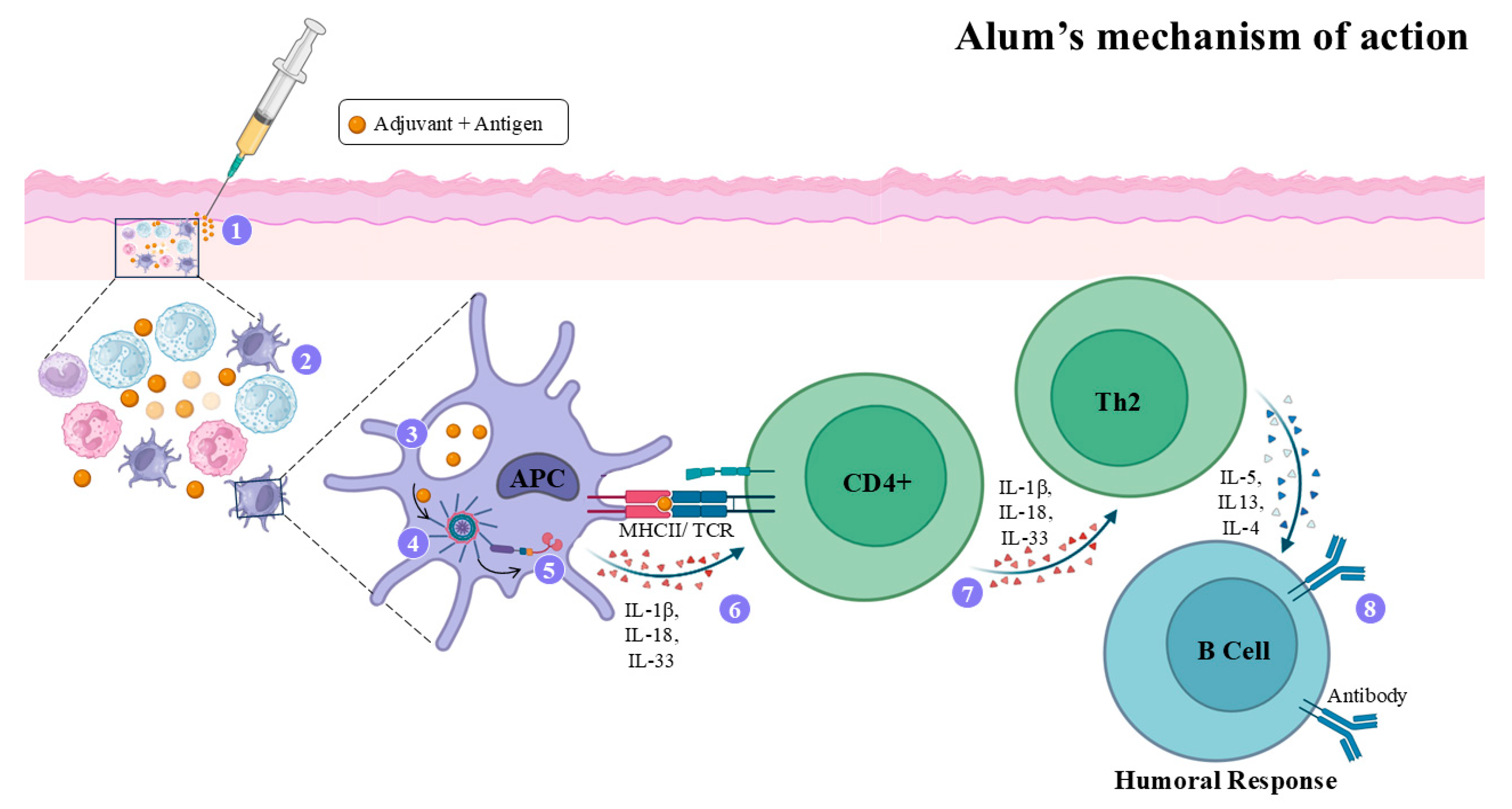

4.2. Alum Adjuvant

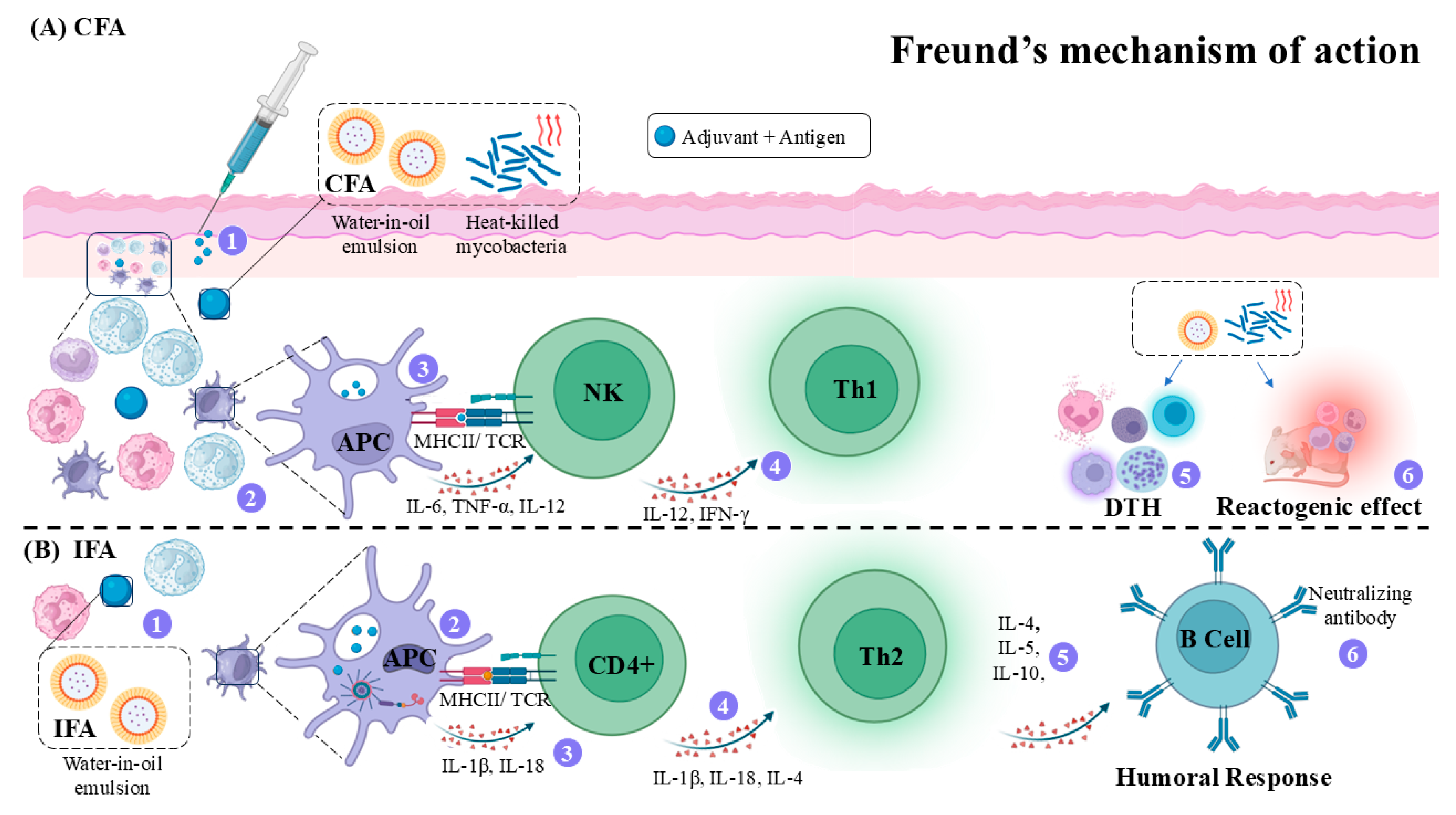

4.3. Freund’s Adjuvant (FA)

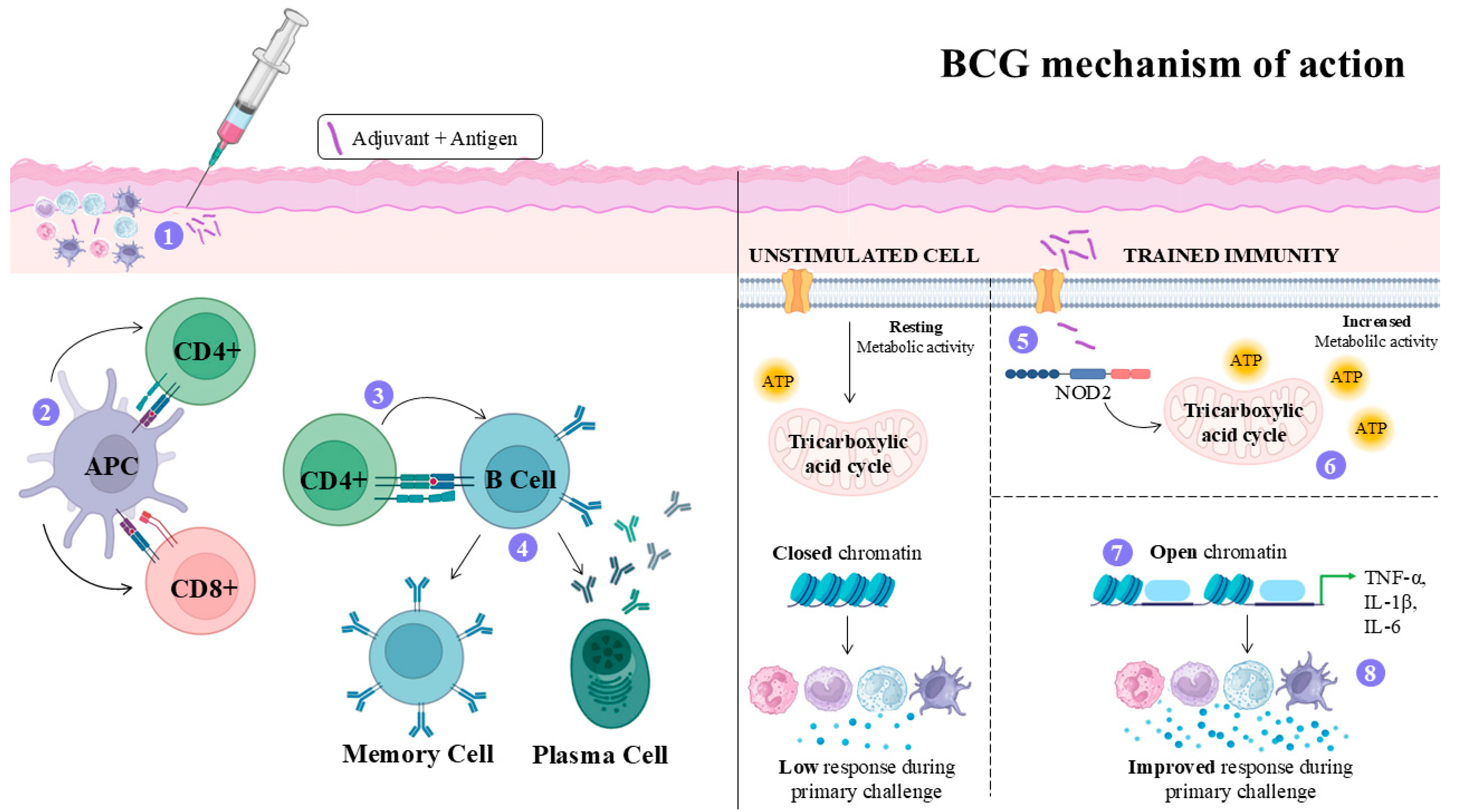

4.4. Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) Adjuvant

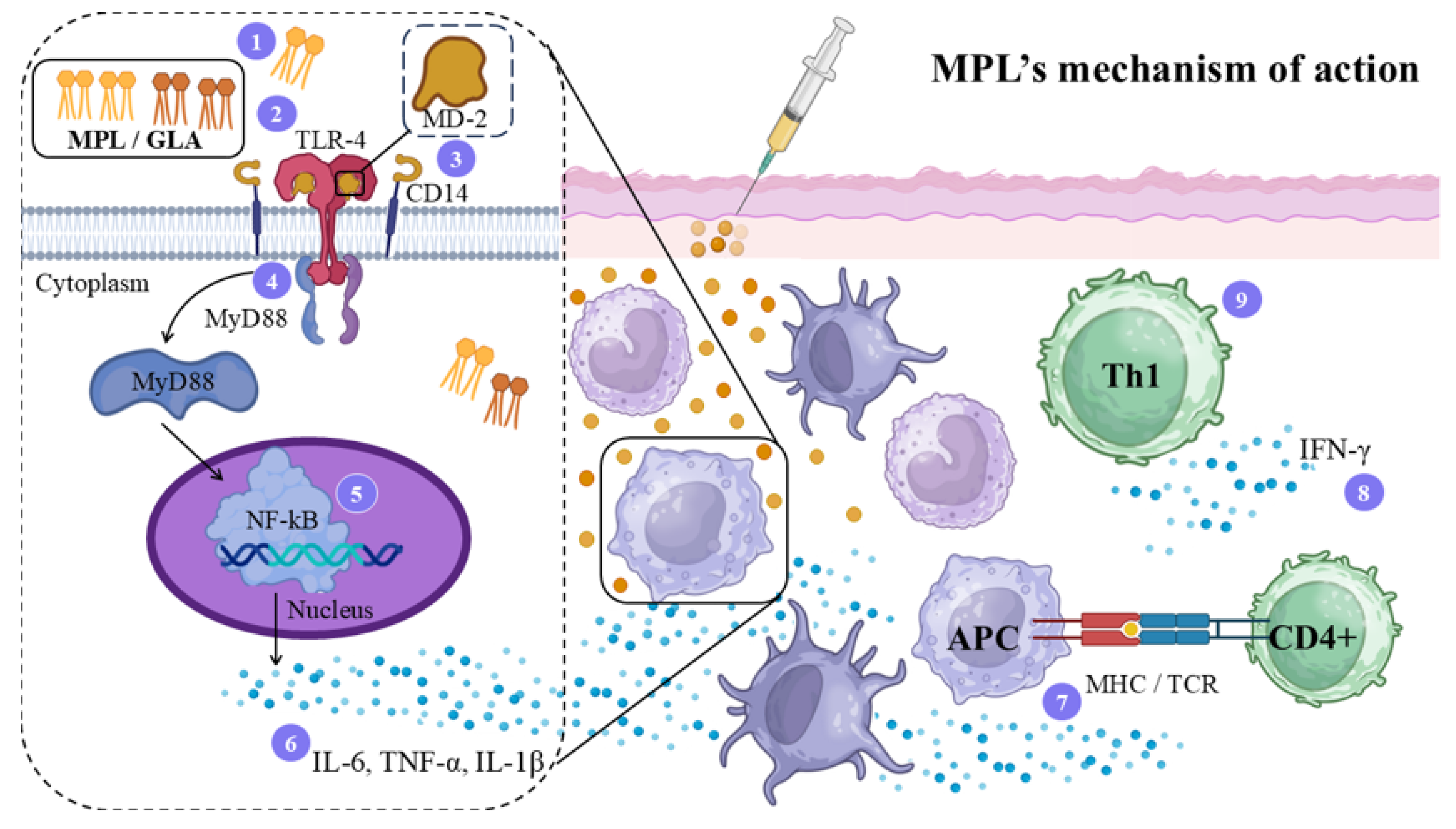

4.5. Monophosphoryl Lipid A (MPL) Adjuvant

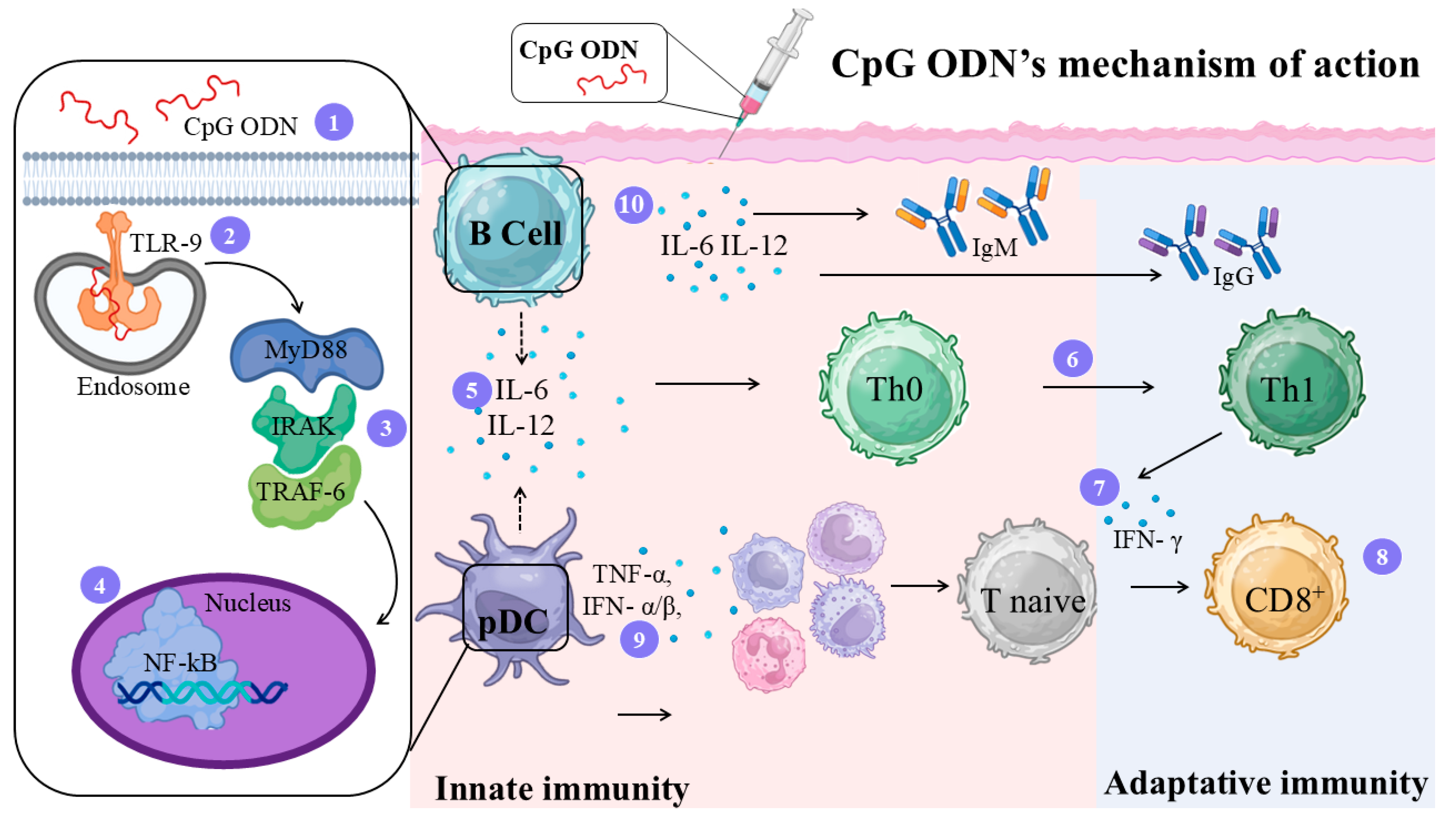

4.6. CpG-Oligodeoxynucleotides (CpG ODN) Adjuvant

5. Vaccines for Leishmaniasis—20 Years of Studies on the First, Second, and Third-Generation Vaccines

5.1. Leishmanization and the Generations of Vaccines Against Leishmaniasis

5.2. First Generation of Leishmania Vaccines

5.3. Second Generation of Leishmania Vaccines

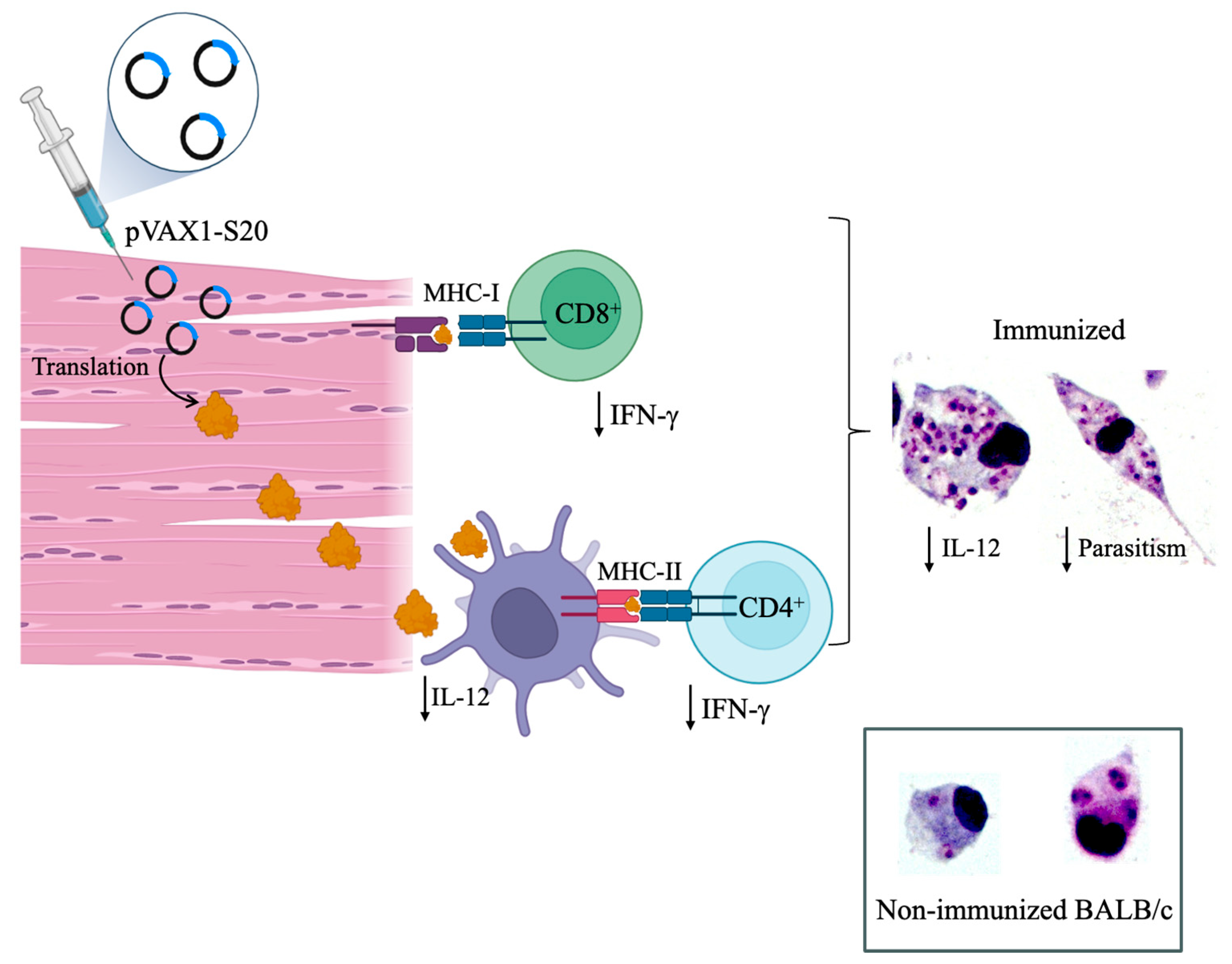

5.4. Third Generation Vaccines

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO/Leishmaniasis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Passero, L.F.D.; Cruz, L.A.; Santos-Gomes, G.; Rodrigues, E.; Laurenti, M.D.; Lago, J.H.G. Conventional Versus Natural Alternative Treatments for Leishmaniasis: A Review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, D.L.; Brodin, T.N.; Turco, S.J. Developmental Modification of the Lipophosphoglycan from Leishmania Major Promastigotes during Metacyclogenesis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1990, 42, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde, L.; Maciel, G.; de Assis, G.M.; Freire-de-Lima, L.; Nico, D.; Vale, A.; Freire-de-Lima, C.G.; Morrot, A. Humoral Response in Leishmaniasis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1063291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, C.; Röllinghoff, M. The Immune Response to Leishmania: Mechanisms of Parasite Control and Evasion. Int. J. Parasitol. 1998, 28, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Menezes, J.P.; Saraiva, E.M.; da Rocha-Azevedo, B. The Site of the Bite: Leishmania Interaction with Macrophages, Neutrophils and the Extracellular Matrix in the Dermis. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, U.; Osterloh, A. A New View on Cutaneous Dendritic Cell Subsets in Experimental Leishmaniasis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007, 196, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.K.; Carvalho, K.; Passero, L.F.D.; Sousa, M.G.T.; da Matta, V.L.R.; Gomes, C.M.C.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Kallas, G.E.; Silveira, F.T.; Laurenti, M.D. Differential Recruitment of Dendritic Cells Subsets to Lymph Nodes Correlates with a Protective or Permissive T-Cell Response during Leishmania (Viannia) Braziliensis or Leishmania (Leishmania) Amazonensis Infection. Mediators Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, U.; Meißner, A.; Scheidig, C.; Körner, H. CD8α- and Langerin-negative Dendritic Cells, but Not Langerhans Cells, Act as Principal Antigen-presenting Cells in Leishmaniasis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004, 34, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, F.T.; Muller, S.R.; de Souza, A.A.A.; Lainson, R.; Gomes, C.M.C.; Laurenti, M.D.; Corbett, C.E.P. Revisão Sobre a Patogenia Da Leishmaniose Tegumentar Americana Na Amazônia, Com Ênfase à Doença Causada Por Leishmania (V.) Braziliensis e Leishmania (L.) Amazonensis. Rev. Para. De Med. 2008, 22, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Aranha, F.C.S.; Ribeiro, U.; Basse, P.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Laurenti, M.D. Interleukin-2-Activated Natural Killer Cells May Have a Direct Role in the Control of Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis Promastigote and Macrophage Infection. Scand. J. Immunol. 2005, 62, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passero, L.F.D.; Marques, C.; Vale-Gato, I.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Laurenti, M.D.; Santos-Gomes, G. Histopathology, Humoral and Cellular Immune Response in the Murine Model of Leishmania (Viannia) shawi. Parasitol. Int. 2010, 59, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurdayal, R.; Brombacher, F. The Role of IL-4 and IL-13 in Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Immunol. Lett. 2014, 161, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passero, L.F.D.; Sacomori, J.V.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Laurenti, M.D. Response of CD4+ and CD8+ T Lymphocytes in the Evolution of Leishmania (Viannia) shawi Infection. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 21, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewig, N.; Kissenpfennig, A.; Malissen, B.; Veit, A.; Bickert, T.; Fleischer, B.; Mostböck, S.; Ritter, U. Priming of CD8+ and CD4+ T Cells in Experimental Leishmaniasis Is Initiated by Different Dendritic Cell Subtypes. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Bhattacharya, P.; Joshi, A.B.; Ismail, N.; Dey, R.; Nakhasi, H.L. Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine IL-17 in Leishmania Pathogenesis and in Protective Immunity by Leishmania Vaccines. Cell Immunol. 2016, 309, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacellar, O.; Faria, D.; Nascimento, M.; Cardoso, T.M.; Gollob, K.J.; Dutra, W.O.; Scott, P.; Carvalho, E.M. Interleukin 17 Production among Patients with American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, K.; Calzada, J.E.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Saldaña, A.; Laurenti, M.D. Involvement of the Inflammasome and Th17 Cells in Skin Lesions of Human Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis. Mediators Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 9278931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesquini, F.C.; Silveira, F.T.; Passero, L.F.D.; Tomokane, T.Y.; Carvalho, A.K.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Laurenti, M.D. Salivary Gland Homogenates from Wild-Caught Sand Flies Lutzomyia flaviscutellata and Lutzomyia (Psychodopygus) Complexus Showed Inhibitory Effects on Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis and Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis Infection in BALB/c Mice. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 95, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo Albuquerque, L.P.; da Silva, A.M.; de Araújo Batista, F.M.; de Souza Sene, I.; Costa, D.L.; Costa, C.H.N. Influence of Sex Hormones on the Immune Response to Leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 2021, 43, e12874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthianandeswaren, A.; Foote, S.J.; Handman, E. The Role of Host Genetics in Leishmaniasis. Trends Parasitol. 2009, 25, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Queiroz, N.M.G.P.; da Silveira, R.C.V.; de Noronha, A.C.F.; Oliveira, T.M.F.S.; Machado, R.Z.; Starke-Buzetti, W.A. Detection of Leishmania (L.) Chagasi in Canine Skin. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 178, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hommel, M.; Jaffe, C.L.; Travi, B.; Milon, G. Experimental Models for Leishmaniasis and for Testing Anti-Leishmanial Vaccines. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1995, 89, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvar, J.; Cañavate, C.; Molina, R.; Moreno, J.; Nieto, J. Canine Leishmaniasis. In Advances in Parasitology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 57, pp. 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Nylén, S. Immunobiology of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, C.; Nunes, M.; Cristóvão, J.; Campino, L. Experimental Canine Leishmaniasis: Clinical, Parasitological and Serological Follow-Up. Acta Trop. 2010, 116, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenti, M.D.; Rossi, C.N.; Matta, V.L.R.d.; Tomokane, T.Y.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Secundino, N.F.C.; Pimenta, P.F.P.; Marcondes, M. Asymptomatic Dogs Are Highly Competent to Transmit Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum Chagasi to the Natural Vector. Vet. Parasitol. 2013, 196, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melby, P.C.; Chandrasekar, B.; Zhao, W.; Coe, J.E.; Teitelbaum, R.; Hariprashad, J.; Murray, H.W. The Hamster as a Model of Human Visceral Leishmaniasis: Progressive Disease and Impaired Generation of Nitric Oxide in the Face of a Prominent Th1-like Cytokine Response. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 1912–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Chard, L.S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Syrian Hamster as an Animal Model for the Study on Infectious Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Dube, A. Animal Models for Vaccine Studies for Visceral Leishmaniasis. Indian J. Med. Res. 2006, 123, 439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Corbett, C.E.; Paes, R.A.; Laurenti, M.D.; Andrade Júnior, H.F.; Duarte, M.I. Histopathology of Lymphoid Organs in Experimental Leishmaniasis. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 1992, 73, 417–433. [Google Scholar]

- Laurenti, M.D.; Sotto, M.N.; Corbett, C.E.; da Matta, V.L.; Duarte, M.I. Experimental Visceral Leishmaniasis: Sequential Events of Granuloma Formation at Subcutaneous Inoculation Site. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 1990, 71, 791–797. [Google Scholar]

- Olobo, J.O.; Gicheru, M.M.; Anjili, C.O. The African Green Monkey Model for Cutaneous and Visceral Leishmaniasis. Trends Parasitol. 2001, 17, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porrozzi, R.; Pereira, M.S.; Teva, A.; Volpini, A.C.; Pinto, M.A.; Marchevsky, R.S.; Barbosa, A.A.; Grimaldi, G. Leishmania Infantum-Induced Primary and Challenge Infections in Rhesus Monkeys (Macaca mulatta): A Primate Model for Visceral Leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006, 100, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baneth, G.; Koutinas, A.F.; Solano-Gallego, L.; Bourdeau, P.; Ferrer, L. Canine Leishmaniosis-New Concepts and Insights on an Expanding Zoonosis: Part One. Trends Parasitol. 2008, 24, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, A.; Mathur, R.K.; Saha, B. Immune Response to Leishmania Infection. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2004, 119, 238–258. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Colmenares, M.; Soong, L.; Goldsmith-Pestana, K.; Munstermann, L.; Molina, R.; McMahon-Pratt, D. Intradermal Infection Model for Pathogenesis and Vaccine Studies of Murine Visceral Leishmaniasis. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loría-Cervera, E.N.; Andrade-Narvaez, F.J. Animal models for the study of leishmaniasis immunology. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2014, 56, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.I.; Laurenti, M.D.; Andrade Júnior, H.F.; Corbett, C.E. Comparative Study of the Biological Behaviour in Hamster of Two Isolates of Leishmania Characterized Respectively as L. Major-like and L. Donovani. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 1988, 30, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, L.A.; Silveira, F.T.; Campos, M.B.; Brígido, M.d.C.d.O.; Gomes, C.M.C.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Laurenti, M.D. Susceptibility of Cebus Apella Monkey (Primates: Cebidae) to Experimental Leishmania (L.) Infantum Chagasi-Infection. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2011, 53, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.C.G.; Valle, T.Z. Modelos Experimentais Na Leishmaniose Tegumentar Americana. In Leishmanioses do Continente Americano; Conceição-SILVA, F., Alves, C.R., Eds.; SciELO - Editora FIOCRUZ: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014; pp. 293–307. ISBN 9788575415689. [Google Scholar]

- de Moura, T.R.; Novais, F.O.; Oliveira, F.; Clarêncio, J.; Noronha, A.; Barral, A.; Brodskyn, C.; de Oliveira, C.I. Toward a Novel Experimental Model of Infection To Study American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania Braziliensis. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 5827–5834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilho, T.M.; Goldsmith-Pestana, K.; Lozano, C.; Valderrama, L.; Saravia, N.G.; McMahon-Pratt, D. Murine Model of Chronic L. (Viannia) Panamensis Infection: Role of IL-13 in Disease. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010, 40, 2816–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.M.G.; Larangeira, D.F.; Oliveira, P.R.S.; Sampaio, R.B.; Suzart, P.; Nihei, J.S.; Teixeira, M.C.A.; Mengel, J.O.; dos-Santos, W.L.C.; Pontes-de-Carvalho, L. Enhancement of Experimental Cutaneous Leishmaniasis by Leishmania Molecules Is Dependent on Interleukin-4, Serine Protease/Esterase Activity, and Parasite and Host Genetic Backgrounds. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, F.T.; Lainson, R.; Corbett, C.E. Clinical and Immunopathological Spectrum of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis with Special Reference to the Disease in Amazonian Brazil: A Review. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2004, 99, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, K.d.S.; da Costa, S.C.G. Enhancement of Leishmania amazonensis Infection in BCG Non-Responder Mice by BCG-Antigen Specific Vaccine. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 1992, 87, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Cardoso, F.; de Souza, C.d.S.F.; Mendes, V.G.; Abreu-Silva, A.L.; Gonçalves da Costa, S.C.; Calabrese, K.d.S. Immunopathological Studies of Leishmania amazonensis Infection in Resistant and in Susceptible Mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 1933–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, J.; Sun, J.; Soong, L. Impaired Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines at Early Stages of Infection with Leishmania amazonensis. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 4278–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, V.F.; Ransatto, V.A.O.; Conceição-Silva, F.; Molinaro, E.; Ferreira, V.; Coutinho, S.G.; McMahon-Pratt, D.; Grimaldi, G., Jr. Leishmania amazonensis:The Asian Rhesus Macaques (Macaca Mulatta) as an Experimental Model for Study of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Exp. Parasitol. 1996, 82, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenti, M.D.; Passero, L.F.D.; Tomokane, T.Y.; Francesquini, F.d.C.; Rocha, M.C.; Gomes, C.M.d.C.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Silveira, F.T. Dynamic of the Cellular Immune Response at the Dermal Site of Leishmania (L.) Amazonensis and Leishmania (V.) Braziliensis Infection in Sapajus Apella Primate. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 134236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeKrey, G.K.; Lima, H.C.; Titus, R.G. Analysis of the Immune Responses of Mice to Infection with Leishmania Braziliensis. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 827–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boroumand, H.; Badie, F.; Mazaheri, S.; Seyedi, Z.S.; Nahand, J.S.; Nejati, M.; Baghi, H.B.; Abbasi-Kolli, M.; Badehnoosh, B.; Ghandali, M.; et al. Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles Against Viral Infections. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 643953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnapriya, S.; Keerti; Sahasrabuddhe, A.A.; Dube, A. Visceral Leishmaniasis: An Overview of Vaccine Adjuvants and Their Applications. Vaccine 2019, 37, 3505–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmour, I.; Islam, N. Recent Advances on Chitosan as an Adjuvant for Vaccine Delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, A.; Preiss, S.; Da Silva, F.T.; Garçon, N. Vaccine Adjuvants: From 1920 to 2015 and Beyond. Vaccines 2015, 3, 320–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciolà, A.; Visalli, G.; Laganà, A.; Di Pietro, A. An Overview of Vaccine Adjuvants: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Vaccines 2022, 10, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, A.; Omer, S.B. Why and How Vaccines Work. Cell 2020, 183, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmick, S.; Ravindran, R.; Ali, N. IL-4 Contributes to Failure, and Colludes with IL-10 to Exacerbate Leishmania Donovani Infection Following Administration of a Subcutaneous Leishmanial Antigen Vaccine. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheat, W.H.; Arthun, E.N.; Spencer, J.S.; Regan, D.P.; Titus, R.G.; Dow, S.W. Immunization against Full-Length Protein and Peptides from the Lutzomyia Longipalpis Sand Fly Salivary Component Maxadilan Protects against Leishmania Major Infection in a Murine Model. Vaccine 2017, 35, 6611–6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Oryan, A.; Hatam, G. Immunotherapy in Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Immunol. Lett. 2021, 233, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibaki, A.; Katz, S.I. Induction of Skewed Th1/Th2 T-Cell Differentiation via Subcutaneous Immunization with Freund’s Adjuvant. Exp. Dermatol 2002, 11, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiau, A.; Matthys, P. Modes of Action of Freund’s Adjuvants in Experimental Models of Autoimmune Diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2001, 70, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerwenka, A.; Lanier, L.L. Ligands for Natural Killer Cell Receptors: Redundancy or Specificity. Immunol. Rev. 2001, 181, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.S.; Marrack, P. Old and New Adjuvants. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017, 47, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, H.C.; Karulin, A.Y.; Tary-Lehmann, M.; Hesse, M.D.; Radeke, H.; Heeger, P.S.; Trezza, R.P.; Heinzel, F.P.; Forsthuber, T.; Lehmann, P.V. Adjuvant-Guided Type-1 and Type-2 Immunity: Infectious/Noninfectious Dichotomy Defines the Class of Response. J. Immunol. 1999, 162, 3942–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, L.R.; Fox, J.G. Institutional Policies and Guidelines on Adjuvants and Antibody Production. ILAR J. 1995, 37, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Jin, S.; Gilmartin, L.; Toth, I.; Hussein, W.M.; Stephenson, R.J. Advances in Infectious Disease Vaccine Adjuvants. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchner, M.; Reinke, S.; Milicic, A. Tlr Agonists as Vaccine Adjuvants Targeting Cancer and Infectious Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabazzadeh Tehrani, N.; Mahdavi, M.; Maleki, F.; Zarrati, S.; Tabatabaie, F. The Role of Montanide ISA 70 as an Adjuvant in Immune Responses against Leishmania major Induced by Thiol-Specific Antioxidant-Based Protein Vaccine. J. Parasit. Dis. 2016, 40, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Paik, D.; Naskar, K.; Chakraborti, T. Leishmania Donovani Serine Protease Encapsulated in Liposome Elicits Protective Immunity in Experimental Visceral Leishmaniasis. Microbes Infect. 2018, 20, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdiyev, A.M.; Cakir Koc, R.; Bagirova, M.; Elcicek, S.; Baydar, S.Y.; Oztel, O.N.; Abamor, E.S.; Ates, S.C.; Topuzogullari, M.; Isoglu Dincer, S.; et al. A New Approach for Development of Vaccine against Visceral Leishmaniasis: Lipophosphoglycan and Polyacrylic Acid Conjugates. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masih, S.; Arora, S.K.; Vasishta, R.K. Efficacy of Leishmania Donovani Ribosomal P1 Gene as DNA Vaccine in Experimental Visceral Leishmaniasis. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 129, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroff, S.A.; Branch, A. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (B.C.G.): Animal Experimentation and Prophylactic Immunization of Children. Am. J. Public. Health Nations Health 1928, 18, 843–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki-Nakashimada, M.A.; Unzueta, A.; Berenise Gámez-González, L.; González-Saldaña, N.; Sorensen, R.U. BCG: A Vaccine with Multiple Faces. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020, 16, 1841–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Gao, L.; Wu, X.; Fan, Y.; Liu, M.; Peng, L.; Song, J.; Li, B.; Liu, A.; Bao, F. BCG-Induced Trained Immunity: History, Mechanisms and Potential Applications. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balodi, D.C.; Anand, A.; Ramalingam, K.; Yadav, S.; Goyal, N. Dipeptidylcarboxypeptidase of Leishmania Donovani: A Potential Vaccine Molecule against Experimental Visceral Leishmaniasis. Cell Immunol. 2022, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.H.L.; Gentil, L.G.; Dias, S.S.; Fedeli, C.E.C.; Katz, S.; Barbiéri, C.L. Immunization with the Cysteine Proteinase Ldccys1 Gene from Leishmania (Leishmania) Chagasi and the Recombinant Ldccys1 Protein Elicits Protective Immune Responses in a Murine Model of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2008, 26, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrevanian, H.; Jafary, S.P.; Nemati, S.; Farahmand, M.; Omidinia, E. Evaluation of Anti-Leishmanial Effects of Killed Leishmania Vaccine with BCG Adjuvant in BALB/c Mice Infected with Leishmania Major MRHO/IR/75/ER. FoliA Parasitol. 2013, 60, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.Y.; Fathy, F.M.; Hegazy, E.H.; Hussein, E.D.; Eissa, M.M.; Said, D.E. The Adjuvant Effects of IL-12 and BCG on Autoclaved Leishmania Major Vaccine in Experimental Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. J. Egypt Soc. Parasitol. 2006, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnapriya, S.; Keerti; Yadav, N.K.; Dube, A.; Sahasrabuddhe, A.A. A Chimera of Th1 Stimulatory Proteins of Leishmania Donovani Offers Moderate Immunotherapeutic Efficacy with a Th1-Inclined Immune Response against Visceral Leishmaniasis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 8845826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetab Boushehri, M.A.; Lamprecht, A. TLR4-Based Immunotherapeutics in Cancer: A Review of the Achievements and Shortcomings. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 4777–4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schülke, S.; Flaczyk, A.; Vogel, L.; Gaudenzio, N.; Angers, I.; Löschner, B.; Wolfheimer, S.; Spreitzer, I.; Qureshi, S.; Tsai, M.; et al. MPLA Shows Attenuated Pro-Inflammatory Properties and Diminished Capacity to Activate Mast Cells in Comparison with LPS. Allergy 2015, 70, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, V.S.; Duthie, M.S.; Fox, C.B.; Matlashewski, G.; Reed, S.G. Adjuvants for Leishmania Vaccines: From Models to Clinical Application. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 23564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Onofrio, V.; Santana, A.C.; Pauwels, M.; Waerlop, G.; Willems, A.; De Boever, F.; Müller, M.; Sehr, P.; Waterboer, T.; Leroux-Roels, I.; et al. AS04 Drives Superior Cross-Protective Antibody Response by Increased NOTCH Signaling of Dendritic Cells and Proliferation of Memory B Cells. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1623405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beran, J. Safety and Immunogenicity of a New Hepatitis B Vaccine for the Protection of Patients with Renal Insufficiency Including Pre-Haemodialysis and Haemodialysis Patients. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2008, 8, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, A.; Kaur, H.; Kaur, S. Evaluation of the Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy of Killed Leishmania Donovani Antigen along with Different Adjuvants against Experimental Visceral Leishmaniasis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 204, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Vasishta, R.K.; Arora, S.K. Vaccination with a Novel Recombinant Leishmania Antigen plus MPL Provides Partial Protection against L. Donovani Challenge in Experimental Model of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Exp. Parasitol. 2009, 121, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeiky, Y.A.W.; Coler, R.N.; Brannon, M.; Stromberg, E.; Greeson, K.; Thomas Crane, R.; Campos-Neto, A.; Reed, S.G. Protective Efficacy of a Tandemly Linked, Multi-Subunit Recombinant Leishmanial Vaccine (Leish-111f) Formulated in MPL® Adjuvant. Vaccine 2002, 20, 3292–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, R.T.; Vale, A.M.; França Da Silva, J.C.; Da Costa, R.T.; Quetz, J.D.S.; Martins Filho, O.A.; Reis, A.B.; Corrêa Oliveira, R.; Machado-Coelho, G.L.; Bueno, L.L.; et al. Immunogenicity in Dogs of Three Recombinant Antigens (TSA, LeIF and LmSTI1) Potential Vaccine Candidates for Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis. Vet. Res. 2005, 36, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradoni, L.; Foglia Manzillo, V.; Pagano, A.; Piantedosi, D.; De Luna, R.; Gramiccia, M.; Scalone, A.; Di Muccio, T.; Oliva, G. Failure of a Multi-Subunit Recombinant Leishmanial Vaccine (MML) to Protect Dogs from Leishmania Infantum Infection and to Prevent Disease Progression in Infected Animals. Vaccine 2005, 23, 5245–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanos-Cuentas, A.; Calderón, W.; Cruz, M.; Ashman, J.A.; Alves, F.P.; Coler, R.N.; Bogatzki, L.Y.; Bertholet, S.; Laughlin, E.M.; Kahn, S.J.; et al. A Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of the LEISH-F1+MPL-SE Vaccine When Used in Combination with Sodium Stibogluconate for the Treatment of Mucosal Leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2010, 28, 7427–7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Jiang, M.; Yu, W.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Jia, Q.; Guan, X.; Zhang, W. CpG-Based Nanovaccines for Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 5281–5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, C.; Zhao, G.; Steinhagen, F.; Kinjo, T.; Klinman, D.M. CpG DNA as a Vaccine Adjuvant. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2011, 10, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhu, H.; Xia, X.; Liang, Z.; Ma, X.; Vaccine, B.S. Vaccine Adjuvants: Understanding the Structure and Mechanism of Adjuvanticity. Vaccine 2019, 37, 3167–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollmer, J.; Krieg, A.M. Immunotherapeutic Applications of CpG Oligodeoxynucleotide TLR9 Agonists. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daifalla, N.S.; Bayih, A.G.; Gedamu, L. Leishmania Donovani Recombinant Iron Superoxide Dismutase B1 Protein in the Presence of TLR-Based Adjuvants Induces Partial Protection of BALB/c Mice against Leishmania Major Infection. Exp. Parasitol. 2012, 131, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafaghodi, M.; Eskandari, M.; Khamesipour, A.; Jaafari, M.R. Alginate Microspheres Encapsulated with Autoclaved Leishmania Major (ALM) and CpG-ODN Induced Partial Protection and Enhanced Immune Response against Murine Model of Leishmaniasis. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 129, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenellenbogen, I. Vaccination against Oriental Sore. Arch. Derm. Syphilol. 1944, 50, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daifalla, N.S.; Bayih, A.G.; Gedamu, L. Immunogenicity of Leishmania Donovani Iron Superoxide Dismutase B1 and Peroxidoxin 4 in BALB/c Mice: The Contribution of Toll-like Receptor Agonists as Adjuvant. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 129, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, A.; Medzhitov, R. Toll-like Receptor Control of the Adaptive Immune Responses. Nat. Immunol. 2004, 5, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutwiri, G. TLR9 Agonists: Immune Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential in Domestic Animals. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2012, 148, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaati, M.; Saidijam, M.; Soleimani, M.; Hazrati, F.; Mirzaei, R.; Amirheidari, B.; Tanzadehpanah, H.; Karampoor, S.; Kazemi, S.; Yavari, B.; et al. A Brief Review on Dna Vaccines in the Era of COVID-19. Future Virol. 2022, 17, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoumani, M.E.; Voyiatzaki, C.; Efstathiou, A. Malaria Vaccines: From the Past towards the mRNA Vaccine Era. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, I.; Joshi, J.; Kaur, S. Leishmania Vaccine Development: A Comprehensive Review. Cell Immunol. 2024, 399–400, 104826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamesipour, A.; Dowlati, Y.; Asilian, A.; Hashemi-Fesharki, R.; Javadi, A.; Noazin, S.; Modabber, F. Leishmanization: Use of an old method for evaluation of candidate vaccines against leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2005, 23, 3642–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senekji, H.A.; Beattie, C.P. Artificial Infection and Immunization of Man with Cultures of Leishmania Tropica. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1941, 34, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naggan, L.; Gunders, A.E.; Michaeli, D. Follow-up Study of a Vaccination Programme against Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1972, 66, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadirn, A.; Javadian, E.; Mohebali, M. The Experience of Leishmanization in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern IRevelent 1997, 3, 284. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, N.; Karmakar, S.; Bhattacharya, P.; Dey, R.; Nakhasi, H.L. Immunization with Leishmania major Centrin Knock-out (LmCen −/−) Parasites Induces Skin Resident Memory T Cells That Plays a Role in Protection against Wild Type Infection (LmWT). J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 196.29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laabs, E.M.; Wu, W.; Mendez, S. Vaccination with Live Leishmania major and CpG DNA Promotes Interleukin-2 Production by Dermal Dendritic Cells and NK Cell Activation. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009, 16, 1601–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, S.; Tabbara, K.; Belkaid, Y.; Bertholet, S.; Verthelyi, D.; Klinman, D.; Seder, R.A.; Sacks, D.L. Coinjection with CpG-Containing Immunostimulatory Oligodeoxynucleotides Reduces the Pathogenicity of a Live Vaccine against Cutaneous Leishmaniasis but Maintains Its Potency and Durability. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 5121–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizbani, A.; Taheri, T.; Zahedifard, F.; Taslimi, Y.; Azizi, H.; Azadmanesh, K.; Papadopoulou, B.; Rafati, S. Recombinant Leishmania Tarentolae Expressing the A2 Virulence Gene as a Novel Candidate Vaccine against Visceral Leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2009, 28, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, M.; Tremblay, M.J.; Ouellette, M.; Papadopoulou, B. Live Nonpathogenic Parasitic Vector as a Candidate Vaccine against Visceral Leishmaniasis. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 6372–6382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarzian, N.; Noroozbeygi, M.; Haji Molla Hoseini, M.; Yeganeh, F. Evaluation of Leishmanization Using Iranian Lizard Leishmania Mixed With CpG-ODN as a Candidate Vaccine Against Experimental Murine Leishmaniasis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshvar, H.; Namazi, M.J.; Kamiabi, H.; Burchmore, R.; Cleaveland, S.; Phillips, S. Gentamicin-Attenuated Leishmania Infantum Vaccine: Protection of Dogs against Canine Visceral Leishmaniosis in Endemic Area of Southeast of Iran. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoudi, N.; Khamesipour, A.; Mahboudi, F.; McMaster, W.R. A Dual Drug Sensitive L. Major Induces Protection without Lesion in C57BL/6 Mice. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrión, J.; Folgueira, C.; Soto, M.; Fresno, M.; Requena, J.M. Leishmania Infantum HSP70-II Null Mutant as Candidate Vaccine against Leishmaniasis: A Preliminary Evaluation. Parasit. Vectors 2011, 4, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Ismail, N.; Oliveira, F.; Oristian, J.; Zhang, W.W.; Kaviraj, S.; Singh, K.P.; Mondal, A.; Das, S.; Pandey, K.; et al. Preclinical Validation of a Live Attenuated Dermotropic Leishmania Vaccine against Vector Transmitted Fatal Visceral Leishmaniasis. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Karmakar, S.; Bhattacharya, P.; Sepahpour, T.; Takeda, K.; Hamano, S.; Matlashewski, G.; Satoskar, A.R.; Gannavaram, S.; Dey, R.; et al. Leishmania Major Centrin Gene-Deleted Parasites Generate Skin Resident Memory T-Cell Immune Response Analogous to Leishmanization. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCall, L.-I.; Zhang, W.-W.; Ranasinghe, S.; Matlashewski, G. Leishmanization Revisited: Immunization with a Naturally Attenuated Cutaneous Leishmania Donovani Isolate from Sri Lanka Protects against Visceral Leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2013, 31, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, N.; Tate, C.A.; Warburton, C.; Murray, A.; Mahboudi, F.; McMaster, W.R. Development of a Recombinant Leishmania Major Strain Sensitive to Ganciclovir and 5-Fluorocytosine for Use as a Live Vaccine Challenge in Clinical Trials. Vaccine 2005, 23, 1170–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, N.C.; Kimblin, N.; Secundino, N.; Kamhawi, S.; Lawyer, P.; Sacks, D.L. Vector Transmission of Leishmania Abrogates Vaccine-Induced Protective Immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrink, W.; Tavares, C.A.P.; de Deus, R.B.; Pinheiro, M.B.; Guimarães, T.M.P.D.; de Andrade, H.M.; da Costa, C.A.; de Toledo, V.d.P.C.P. Comparative Evaluation of Phenol and Thimerosal as Preservatives for a Candidate Vaccine against American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2010, 105, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutiso, J.M.; Macharia, J.C.; Mutisya, R.M.; Taracha, E. Subcutaneous Immunization against Leishmania Major—Infection in Mice: Efficacy of Formalin-Killed Promastigotes Combined with Adjuvants. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2010, 52, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germanó, M.J.; Lozano, E.S.; Sanchez, M.V.; Bruna, F.A.; García-Bustos, M.F.; Lochedino, A.L.S.; Salomón, M.C.; Fernandes, A.P.; Mackern-Oberti, J.P.; Cargnelutti, D.E. Evaluation of Different Total Leishmania amazonensis Antigens for the Development of a First-Generation Vaccine Formulated with a Toll-like Receptor-3 Agonist to Prevent Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e200067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noazin, S.; Modabber, F.; Khamesipour, A.; Smith, P.G.; Moulton, L.H.; Nasseri, K.; Sharifi, I.; Khalil, E.A.G.; Bernal, I.D.V.; Antunes, C.M.F.; et al. First Generation Leishmaniasis Vaccines: A Review of Field Efficacy Trials. Vaccine 2008, 26, 6759–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handman, E. Leishmaniasis: Current Status of Vaccine Development. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenfell, R.F.Q.; Marques-da-Silva, E.A.; Souza-Testasicca, M.C.; Coelho, E.A.F.; Fernandes, A.P.; Afonso, L.C.C.; Rezende, S.A. Antigenic Extracts of Leishmania Braziliensis and Leishmania amazonensis Associated with Saponin Partially Protects BALB/c Mice against Leishmania Chagasi Infection by Suppressing IL-10 and IL-4 Production. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2010, 105, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunchetti, R.C.; Corrêa-Oliveira, R.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Teixeira-Carvalho, A.; Roatt, B.M.; de Oliveira Aguiar-Soares, R.D.; de Souza, J.V.; das Dores Moreira, N.; Malaquias, L.C.C.; Mota e Castro, L.L.; et al. Immunogenicity of a Killed Leishmania Vaccine with Saponin Adjuvant in Dogs. Vaccine 2007, 25, 7674–7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunchetti, R.C.; Corrêa-Oliveira, R.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Teixeira-Carvalho, A.; Roatt, B.M.; Aguiar-Soares, R.D.d.O.; Coura-Vital, W.; de Abreu, R.T.; Malaquias, L.C.C.; Gontijo, N.F.; et al. A Killed Leishmania Vaccine with Sand Fly Saliva Extract and Saponin Adjuvant Displays Immunogenicity in Dogs. Vaccine 2008, 26, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunchetti, R.C.; Reis, A.B.; da Silveira-Lemos, D.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Corrêa-Oliveira, R.; Bethony, J.; Vale, A.M.; da Silva Quetz, J.; Bueno, L.L.; França-Silva, J.C.; et al. Antigenicity of a Whole Parasite Vaccine as Promising Candidate against Canine Leishmaniasis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2008, 85, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, I.D.; Gilchrist, K.; Arbelaez, M.P.; Rojas, C.A.; Puerta, J.A.; Antunes, C.M.F.; Zicker, F.; Modabber, F. Failure of a Killed Leishmania amazonensis Vaccine against American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in Colombia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005, 99, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, B.; Vadalà, M.; Roncati, L.; Garelli, A.; Scandone, F.; Bondi, M.; Cermelli, C. The Long-standing History of Corynebacterium Parvum, Immunity, and Viruses. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2429–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passero, L.F.D.; da Costa Bordon, M.L.A.; de Carvalho, A.K.; Martins, L.M.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Laurenti, M.D. Exacerbation of Leishmania (Viannia) Shawi Infection in BALB/c Mice after Immunization with Soluble Antigen from Amastigote Forms. APMIS 2010, 118, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, A.B.; Teixeira-Carvalho, A.; Giunchetti, R.C.; Guerra, L.L.; Carvalho, M.G.; Mayrink, W.; Genaro, O.; Corrêa-Oliveira, R.; Martins-Filho, O.A. Phenotypic Features of Circulating Leucocytes as Immunological Markers for Clinical Status and Bone Marrow Parasite Density in Dogs Naturally Infected by Leishmania Chagasi. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2006, 146, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, A.P.; McClellan, H.A.; Rausch, K.M.; Zhu, D.; Whitmore, M.D.; Singh, S.; Martin, L.B.; Wu, Y.; Giersing, B.K.; Stowers, A.W.; et al. Montanide® ISA 720 Vaccines: Quality Control of Emulsions, Stability of Formulated Antigens, and Comparative Immunogenicity of Vaccine Formulations. Vaccine 2005, 23, 2530–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, E.A.G.; Musa, A.M.; Modabber, F.; El-Hassan, A.M. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Candidate Vaccine for Visceral Leishmaniasis (Alum-Precipitated Autoclaved Leishmania Major + BCG) in Children: An Extended Phase II Study. Ann. Trop. Paediatr. 2006, 26, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, K.W.; Birnbaum, R.; Haskell, J.; Vanchinathan, V.; Greger, S.; Narayan, R.; Chang, P.-L.; Tran, T.A.; Hickerson, S.M.; Beverley, S.M.; et al. Killed but Metabolically Active Leishmania Infantum as a Novel Whole-Cell Vaccine for Visceral Leishmaniasis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratti, J.E.S.; Ramos, T.D.; Pereira, J.C.; da Fonseca-Martins, A.M.; Maciel-Oliveira, D.; Oliveira-Silva, G.; de Mello, M.F.; Chaves, S.P.; Gomes, D.C.O.; Diaz, B.L.; et al. Efficacy of Intranasal LaAg Vaccine against Leishmania amazonensis Infection in Partially Resistant C57Bl/6 Mice. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MALAFAIA, G.; SERAFIM, T.D.; SILVA, M.E.; PEDROSA, M.L.; REZENDE, S.A. Protein-energy Malnutrition Decreases Immune Response to Leishmania Chagasi Vaccine in BALB/c Mice. Parasite Immunol. 2009, 31, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, R.; Bhowmick, S.; Das, A.; Ali, N. Comparison of BCG, MPL and Cationic Liposome Adjuvant Systems in Leishmanial Antigen Vaccine Formulations against Murine Visceral Leishmaniasis. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trotta, T.; Fasanella, A.; Scaltrito, D.; Gradoni, L.; Mitolo, V.; Brandonisio, O.; Acquafredda, A.; Panaro, M.A. Comparison between Three Adjuvants for a Vaccine against Canine Leishmaniasis: In Vitro Evaluation of Macrophage Killing Ability. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 33, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coler, R.N.; Reed, S.G. Second-Generation Vaccines against Leishmaniasis. Trends Parasitol. 2005, 21, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stober, C.B.; Lange, U.G.; Mark, †; Roberts, T.M.; Alcami, A.; Blackwell, J.M. IL-10 from Regulatory T Cells Determines Vaccine Efficacy in Murine Leishmania Major Infection. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 2517–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didwania, N.; Bhowmick, S.; Sabur, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Ali, N. Evaluation of Leishmania Homolog of Activated C Kinase (LACK) of Leishmania Donovani in Comparison to Glycoprotein 63 as a Vaccine Candidate against Visceral Leishmaniasis. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, J.; Nieto, J.; Masina, S.; Cañavate, C.; Cruz, I.; Chicharro, C.; Carrillo, E.; Napp, S.; Reymond, C.; Kaye, P.M.; et al. Immunization with H1, HASPB1 and MML Leishmania Proteins in a Vaccine Trial against Experimental Canine Leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2007, 25, 5290–5300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhowmick, S.; Ravindran, R.; Ali, N. Gp63 in Stable Cationic Liposomes Confers Sustained Vaccine Immunity to Susceptible BALB/c Mice Infected with Leishmania Donovani. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.; Carrillo, E.; Sánchez-Sampedro, L.; Sánchez, C.; Ibarra-Meneses, A.V.; Jimenez, M.A.; Almeida, V.d.A.; Esteban, M.; Moreno, J. Antigenicity of Leishmania-Activated C-Kinase Antigen (LACK) in Human Peripheral 181-Blood Mononuclear Cells, and Protective Effect of Prime-Boost Vaccination With PCI-Neo-LACK Plus Attenuated LACK-Expressing Vaccinia Viruses in Hamsters. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, M.; Atayde, V.D.; Isnard, A.; Hassani, K.; Shio, M.T. Leishmania Virulence Factors: Focus on the Metalloprotease GP63. Microbes Infect. 2012, 14, 1377–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Sobti, R.C.; Kaur, S. Cocktail of Gp63 and Hsp70 Induces Protection against Leishmania Donovani in BALB/c Mice. Parasite Immunol. 2011, 33, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Thakur, A.; Kaur, S. Protective Immunity Using MPL-A and Autoclaved Leishmania Donovani as Adjuvants along with a Cocktail Vaccine in Murine Model of Visceral Leishmaniasis. J. Parasit. Dis. 2013, 37, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, S.; Ali, N. Identification of Novel Leishmania Donovani Antigens That Help Define Correlates of Vaccine-Mediated Protection in Visceral Leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagill, R.; Kaur, T.; Joshi, J.; Kaur, S. Immunogenicity and Efficacy of Recombinant 78 KDa Antigen of Leishmania Donovani Formulated in Various Adjuvants against Murine Visceral Leishmaniasis. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2015, 8, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, B.; Nezafat, N.; Zare, B.; Erfani, N.; Akbari, M.; Ghasemi, Y.; Rahbar, M.R.; Hatam, G.R. A New Multi-Epitope Peptide Vaccine Induces Immune Responses and Protection against Leishmania Infantum in BALB/c Mice. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020, 209, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lage, D.P.; Ribeiro, P.A.F.; Dias, D.S.; Mendonça, D.V.C.; Ramos, F.F.; Carvalho, L.M.; de Oliveira, D.; Steiner, B.T.; Martins, V.T.; Perin, L.; et al. A Candidate Vaccine for Human Visceral Leishmaniasis Based on a Specific T Cell Epitope-Containing Chimeric Protein Protects Mice against Leishmania Infantum Infection. npj Vaccines 2020, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, R.; Marques, C.; Rodrigues, O.R.; Santos-Gomes, G.M. Immunization with Leishmania Infantum Released Proteins Confers Partial Protection against Parasite Infection with a Predominant Th1 Specific Immune Response. Vaccine 2007, 25, 4525–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passero, L.F.D.; Marques, C.; Vale-Gato, I.; Corbett, C.E.P.; Laurenti, M.D.; Santos-Gomes, G. Analysis of the Protective Potential of Antigens Released by Leishmania (Viannia) Shawi Promastigotes. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2012, 304, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrah, P.A.; Patel, D.T.; De Luca, P.M.; Lindsay, R.W.B.; Davey, D.F.; Flynn, B.J.; Hoff, S.T.; Andersen, P.; Reed, S.G.; Morris, S.L.; et al. Multifunctional TH1 Cells Define a Correlate of Vaccine-Mediated Protection against Leishmania Major. Nature Medicine 2007, 13, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Cotrina, J.; Iniesta, V.; Monroy, I.; Baz, V.; Hugnet, C.; Marañon, F.; Fabra, M.; Gómez-Nieto, L.C.; Alonso, C. A Large-Scale Field Randomized Trial Demonstrates Safety and Efficacy of the Vaccine LetiFend® against Canine Leishmaniosis. Vaccine 2018, 36, 1972–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, G.; Teva, A.; Dos-Santos, C.B.; Santos, F.N.; Pinto, I.D.S.; Fux, B.; Leite, G.R.; Falqueto, A. Field Trial of Efficacy of the Leish-Tec® Vaccine against Canine Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania Infantum in an Endemic Area with High Transmission Rates. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, G.; Nieto, J.; Foglia Manzillo, V.; Cappiello, S.; Fiorentino, E.; Di Muccio, T.; Scalone, A.; Moreno, J.; Chicharro, C.; Carrillo, E.; et al. A Randomised, Double-Blind, Controlled Efficacy Trial of the LiESP/QA-21 Vaccine in Naïve Dogs Exposed to Two Leishmania Infantum Transmission Seasons. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, F.S.; Moreira, M.A.B.; Borja-Cabrera, G.P.; Santos, F.N.; Menz, I.; Parra, L.E.; Xu, Z.; Chu, H.J.; Palatnik-de-Sousa, C.B.; Luvizotto, M.C.R. Leishmune® Vaccine Blocks the Transmission of Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis: Absence of Leishmania Parasites in Blood, Skin and Lymph Nodes of Vaccinated Exposed Dogs. Vaccine 2005, 23, 4805–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de A. Luna, E.J.; de S.L. da C. Campos, S.R. O Desenvolvimento de Vacinas Contra as Doenças Tropicais Negligenciadas. Cad. Saude Publica 2020, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatnik-de-Sousa, C.B.; Paraguai-de-Souza, E.; Gomes, E.M.; Borojevic, R. Experimental Murine Leishmania Donovani Infection: Immunoprotection by the Fucose-Mannose Ligand (FML). Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologica 1994, 27, 547–551. [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes, M.; Ikeda, F.A.; Vieira, R.F.C.; Day, M.J.; Lima, V.M.F.; Rossi, C.N.; Perri, S.H.V.; Biondo, A.W. Temporal IgG Subclasses Response in Dogs Following Vaccination against Leishmania with Leishmune®. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 181, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, C.B.; Junior, J.T.M.; De Jesus, C.; Da Silva Souza, B.M.P.; Larangeira, D.F.; Fraga, D.B.M.; Tavares Veras, P.S.; Barrouin-Melo, S.M. Comparison of Two Commercial Vaccines against Visceral Leishmaniasis in Dogs from Endemic Areas: IgG, and Subclasses, Parasitism, and Parasite Transmission by Xenodiagnosis. Vaccine 2014, 32, 1287–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regina-Silva, S.; Feres, A.M.L.T.; França-Silva, J.C.; Dias, E.S.; Michalsky, É.M.; de Andrade, H.M.; Coelho, E.A.F.; Ribeiro, G.M.; Fernandes, A.P.; Machado-Coelho, G.L.L. Field Randomized Trial to Evaluate the Efficacy of the Leish-Tec® Vaccine against Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis in an Endemic Area of Brazil. Vaccine 2016, 34, 2233–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martiniano de Pádua, J.A.; Ribeiro, D.; de Aguilar, V.F.F.; Melo, T.F.; Bueno, L.L.; Grossi de Oliveira, A.L.; Fujiwara, R.T.; Keller, K.M. Overview of Commercial Vaccines Against Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis: Current Landscape and Future Directions. Pathogens 2025, 14, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.; Requena, J.M.; Quijada, L.; Alonso, C. Multicomponent Chimeric Antigen for Serodiagnosis of Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998, 36, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parody, N.; Soto, M.; Requena, J.M.; Alonso, C. Adjuvant Guided Polarization of the Immune Humoral Response against a Protective Multicomponent Antigenic Protein (Q) from Leishmania Infantum. A CpG + Q Mix Protects Balb/c Mice from Infection. Parasite Immunol. 2004, 26, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molano, I.; Alonso, M.G.; Mirón, C.; Redondo, E.; Requena, J.M.; Soto, M.; Nieto, C.G.; Alonso, C. A Leishmania Infantum Multi-Component Antigenic Protein Mixed with Live BCG Confers Protection to Dogs Experimentally Infected with L. Infantum. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2003, 92, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcelén, J.; Iniesta, V.; Fernández-Cotrina, J.; Serrano, F.; Parejo, J.C.; Corraliza, I.; Gallardo-Soler, A.; Marañón, F.; Soto, M.; Alonso, C.; et al. The Chimerical Multi-Component Q Protein from Leishmania in the Absence of Adjuvant Protects Dogs against an Experimental Leishmania Infantum Infection. Vaccine 2009, 27, 5964–5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coler, R.N.; Skeiky, Y.A.W.; Bernards, K.; Greeson, K.; Carter, D.; Cornellison, C.D.; Modabber, F.; Campos-Neto, A.; Reed, S.G. Immunization with a Polyprotein Vaccine Consisting of the T-Cell Antigens Thiol-Specific Antioxidant, Leishmania Major. Stress-Inducible Protein 1, and Leishmania Elongation Initiation Factor Protects against Leishmaniasis. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 4215–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemesre, J.L.; Holzmuller, P.; Cavaleyra, M.; Gonçalves, R.B.; Hottin, G.; Papierok, G. Protection against Experimental Visceral Leishmaniasis Infection in Dogs Immunized with Purified Excreted Secreted Antigens of Leishmania Infantum Promastigotes. Vaccine 2005, 23, 2825–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemesre, J.L.; Holzmuller, P.; Gonçalves, R.B.; Bourdoiseau, G.; Hugnet, C.; Cavaleyra, M.; Papierok, G. Long-Lasting Protection against Canine Visceral Leishmaniasis Using the LiESAp-MDP Vaccine in Endemic Areas of France: Double-Blind Randomised Efficacy Field Trial. Vaccine 2007, 25, 4223–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdoiseau, G.; Hugnet, C.; Gonçalves, R.B.; Vézilier, F.; Petit-Didier, E.; Papierok, G.; Lemesre, J.L. Effective Humoral and Cellular Immunoprotective Responses in Li ESAp-MDP Vaccinated Protected Dogs. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2009, 128, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salay, G.; Dorta, M.L.; Santos, N.M.; Mortara, R.A.; Brodskyn, C.; Oliveira, C.I.; Barbiéri, C.L.; Rodrigues, M.M. Testing of Four Leishmania Vaccine Candidates in a Mouse Model of Infection with Leishmania (Viannia) Braziliensis, the Main Causative Agent of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in the New World. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2007, 14, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamakh-Ayari, R.; Bras-Gonçalves, R.; Bahi-Jaber, N.; Petitdidier, E.; Markikou-Ouni, W.; Aoun, K.; Moreno, J.; Carrillo, E.; Salotra, P.; Kaushal, H.; et al. In Vitro Evaluation of a Soluble Leishmania Promastigote Surface Antigen as a Potential Vaccine Candidate against Human Leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Matos Guedes, H.L.; Pinheiro, R.O.; Chaves, S.P.; De-Simone, S.G.; Rossi-Bergmann, B. Serine Proteases of Leishmania amazonensis as Immunomodulatory and Disease-Aggravating Components of the Crude LaAg Vaccine. Vaccine 2010, 28, 5491–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushawaha, P.K.; Gupta, R.; Tripathi, C.D.P.; Sundar, S.; Dube, A. Evaluation of Leishmania Donovani Protein Disulfide Isomerase as a Potential Immunogenic Protein/Vaccine Candidate against Visceral Leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushawaha, P.K.; Gupta, R.; Tripathi, C.D.P.; Khare, P.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Sundar, S.; Dube, A. Leishmania Donovani Triose Phosphate Isomerase: A Potential Vaccine Target against Visceral Leishmaniasis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez, I.D.; Gilchrist, K.; Martínez, S.; Ramírez-Pineda, J.R.; Ashman, J.A.; Alves, F.P.; Coler, R.N.; Bogatzki, L.Y.; Kahn, S.J.; Beckmann, A.M.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Defined Vaccine for the Prevention of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2009, 28, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, J.; Kumar, S.; Trivedi, S.; Rai, V.K.; Singh, A.; Ashman, J.A.; Laughlin, E.M.; Coler, R.N.; Kahn, S.J.; Beckmann, A.M.; et al. A Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of the LEISH-F1+MPL-SE Vaccine for Use in the Prevention of Visceral Leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2011, 29, 3531–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Amorim, I.F.G.; Freitas, E.; Alves, C.F.; Tafuri, W.L.; Melo, M.N.; Michalick, M.S.M.; da Costa-Val, A.P. Humoral Immunological Profile and Parasitological Statuses of Leishmune® Vaccinated and Visceral Leishmaniasis Infected Dogs from an Endemic Area. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 173, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, D.S.; Ribeiro, P.A.F.; Martins, V.T.; Lage, D.P.; Ramos, F.F.; Dias, A.L.T.; Rodrigues, M.R.; Portela, Á.S.B.; Costa, L.E.; Caligiorne, R.B.; et al. Recombinant Prohibitin Protein of Leishmania Infantum Acts as a Vaccine Candidate and Diagnostic Marker against Visceral Leishmaniasis. Cell Immunol. 2018, 323, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Emerick, S.; Vieira de Carvalho, T.; Meirelles Miranda, B.; Carneiro da Silva, A.; Viana Fialho Martins, T.; Licursi de Oliveira, L.; de Almeida Marques-da-Silva, E. Lipophosphoglycan-3 Protein from Leishmania Infantum Chagasi plus Saponin Adjuvant: A New Promising Vaccine against Visceral Leishmaniasis. Vaccine 2021, 39, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iniguez, E.; Schocker, N.S.; Subramaniam, K.; Portillo, S.; Montoya, A.L.; Al-Salem, W.S.; Torres, C.L.; Rodriguez, F.; Moreira, O.C.; Acosta-Serrano, A.; et al. An α-Gal-Containing Neoglycoprotein-Based Vaccine Partially Protects against Murine Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania Major. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0006039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, R.W.; Felgner, P.L.; Verma, I.M. Cationic Liposome-Mediated RNA Transfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 6077–6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neeli, P.; Chai, D.; Roy, D.; Prajapati, S.; Bonam, S.R. DNA Vaccines in the Post-MRNA Era: Engineering, Applications, and Emerging Innovations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neefjes, J.; Jongsma, M.L.M.; Paul, P.; Bakke, O. Towards a Systems Understanding of MHC Class I and MHC Class II Antigen Presentation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 823–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.A. DNA Vaccines: A Review. J. Intern. Med. 2003, 253, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Jiang, L.; Liao, S.; Wu, F.; Yang, G.; Hou, L.; Liu, L.; Pan, X.; Jia, W.; Zhang, Y. Vaccines’ New Era-RNA Vaccine. Viruses 2023, 15, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Liew, F.Y. Protection against Leishmaniasis by Injection of DNA Encoding a Major Surface Glycoprotein, Gp63, of L. Major. Immunology 1995, 84, 173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman, W.M.; Shen, H.; Brandsma, J.L. DNA Vaccines: Methods and Protocols; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 1588294846. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, S.; Maji, M.; Das, A.; Ali, N. Potency, Efficacy and Durability of DNA/DNA, DNA/Protein and Protein/Protein Based Vaccination Using Gp63 Against Leishmania Donovani in BALB/c Mice. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e14644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, R.; Banerjea, A.C.; Malla, N.; Dubey, M.L. Immunogenicity and Efficacy of Single Antigen Gp63, Polytope and PolytopeHSP70 DNA Vaccines against Visceral Leishmaniasis in Experimental Mouse Model. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.A.; Rezvan, H.; Mcardle, S.E.; Khodadadi, A.; Asteal, F.A.; Rees, R.C. CTL Responses to Leishmania Mexicana Gp63-cDNA Vaccine in a Murine Model. Parasite Immunol. 2009, 31, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; He, J.; Liao, X.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, C.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, H.; Zheng, Z.; Qin, H.; Chen, D.; et al. Development of Dominant Epitope-Based Vaccines Encoding Gp63, Kmp-11 and Amastin against Visceral Leishmaniasis. Immunobiology 2021, 226, 152085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.L.; Stetson, D.B.; Locksley, R.M. Leishmania Major LACK Antigen Is Required for Efficient Vertebrate Parasitization. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Sacks, D.L.; Brown, D.R.; Reiner, S.L.; Charest, H.; Glaichenhaus, N.; Seder, R.A. Vaccination with DNA Encoding the Immunodominant LACK Parasite Antigen Confers Protective Immunity to Mice Infected with Leishmania Major. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 186, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Stobie, L.; Prussin, C.; Sacks, D.L.; Glaichenhaus, N.; Fowell, D.J.; Locksley, R.M.; Chang, J.T.; Wu, C.-Y.; Seder, R.A. Requirements for the Maintenance of Th1 Immunity In Vivo Following DNA Vaccination: A Potential Immunoregulatory Role for CD8+ T Cells. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melby, P.C.; Yang, J.; Zhao, W.; Perez, L.E.; Cheng, J. Leishmania donovani P36(LACK) DNA Vaccine Is Highly Immunogenic but Not Protective against Experimental Visceral Leishmaniasis. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 4719–4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-da-Silva, E.A.; Coelho, E.A.F.; Gomes, D.C.O.; Vilela, M.C.; Masioli, C.Z.; Tavares, C.A.P.; Fernandes, A.P.; Afonso, L.C.C.; Rezende, S.A. Intramuscular Immunization with P36(LACK) DNA Vaccine Induces IFN-γ Production but Does Not Protect BALB/c Mice against Leishmania Chagasi Intravenous Challenge. Parasitol. Res. 2005, 98, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, E.F.; Pinheiro, R.O.; Rayol, A.; Larraga, V.; Rossi-Bergmann, B. Intranasal Vaccination against Cutaneous Leishmaniasis with a Particulated Leishmanial Antigen or DNA Encoding LACK. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 4521–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, D.C.d.O.; Pinto, E.F.; de Melo, L.D.B.; Lima, W.P.; Larraga, V.; Lopes, U.G.; Rossi-Bergmann, B. Intranasal Delivery of Naked DNA Encoding the LACK Antigen Leads to Protective Immunity against Visceral Leishmaniasis in Mice. Vaccine 2007, 25, 2168–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira Gomes, D.C.; Da Silva Costa Souza, B.L.; De Matos Guedes, H.L.; Lopes, U.G.; Rossi-Bergmann, B. Intranasal Immunization with LACK-DNA Promotes Protective Immunity in Hamsters Challenged with Leishmania Chagasi. Parasitology 2011, 138, 1892–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa Souza, B.L.S.; Pinto, E.F.; Bezerra, I.P.S.; Gomes, D.C.O.; Martinez, A.M.B.; Ré, M.I.; de Matos Guedes, H.L.; Rossi-Bergmann, B. Crosslinked Chitosan Microparticles as a Safe and Efficient DNA Carrier for Intranasal Vaccination against Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Vaccine X 2023, 15, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, D.C.O.; Souza, B.L.d.S.C.; Schwedersky, R.P.; Covre, L.P.; de Matos Guedes, H.L.; Lopes, U.G.; Ré, M.I.; Rossi-Bergmann, B. Intranasal Immunization with Chitosan Microparticles Enhances LACK-DNA Vaccine Protection and Induces Specific Long-Lasting Immunity against Visceral Leishmaniasis. Microbes Infect. 2022, 24, 104884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Jiménez, E.; Kochan, G.; Gherardi, M.M.; Esteban, M. MVA-LACK as a Safe and Efficient Vector for Vaccination against Leishmaniasis. Microbes Infect. 2006, 8, 810–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, I.; Alonso, A.; Peris, A.; Marcen, J.M.; Abengozar, M.A.; Alcolea, P.J.; Castillo, J.A.; Larraga, V. Antibiotic Resistance Free Plasmid DNA Expressing LACK Protein Leads towards a Protective Th1 Response against Leishmania Infantum Infection. Vaccine 2009, 27, 6695–6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.; Alcolea, P.J.; Larraga, J.; Peris, M.P.; Esteban, A.; Cortés, A.; Ruiz-García, S.; Castillo, J.A.; Larraga, V. A Non-Replicative Antibiotic Resistance-Free DNA Vaccine Delivered by the Intranasal Route Protects against Canine Leishmaniasis. Front Immunol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Almonacid, C.C.; Kellogg, M.K.; Karamyshev, A.L.; Karamysheva, Z.N. Ribosome Specialization in Protozoa Parasites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.; Alonso, C.; Requena, J.M. The Leishmania Infantum Acidic Ribosomal Protein LiP2a Induces a Prominent Humoral Response in Vivo and Stimulates Cell Proliferation in Vitro and Interferon-Gamma (IFN-γ) Production by Murine Splenocytes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2008, 122, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena, J.M.; Alonso, C.; Soto, M. Evolutionarily Conserved Proteins as Prominent Immunogens during Leishmania Infections. Parasitol. Today 2000, 16, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iborra, S.; Soto, M.; Carrión, J.; Nieto, A.; Fernández, E.; Alonso, C.; Requena, J.M. The Leishmania Infantum Acidic Ribosomal Protein P0 Administered as a DNA Vaccine Confers Protective Immunity to Leishmania Major Infection in BALB/c Mice. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 6562–6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.; Abbehusen, M.; Teixeira, C.; Cunha, J.; Nascimento, I.P.; Fukutani, K.; dos-Santos, W.; Barral, A.; de Oliveira, C.I.; Barral-Netto, M.; et al. Vaccination with Leishmania Infantum Acidic Ribosomal P0 but Not with Nucleosomal Histones Proteins Controls Leishmania Infantum Infection in Hamsters. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reverte, M.; Eren, R.O.; Jha, B.; Desponds, C.; Snäkä, T.; Prevel, F.; Isorce, N.; Lye, L.-F.; Owens, K.L.; Gazos Lopes, U.; et al. The Antioxidant Response Favors Leishmania Parasites Survival, Limits Inflammation and Reprograms the Host Cell Metabolism. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stober, C.B.; Lange, U.G.; Roberts, M.T.M.; Alcami, A.; Blackwell, J.M. Heterologous Priming-Boosting with DNA and Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Expressing Tryparedoxin Peroxidase Promotes Long-Term Memory against Leishmania Major in Susceptible BALB/c Mice. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, A.; Castilho, T.M.; Park, E.; Goldsmith-Pestana, K.; Blackwell, J.M.; McMahon-Pratt, D. TLR1/2 Activation during Heterologous Prime-Boost Vaccination (DNA-MVA) Enhances CD8+ T Cell Responses Providing Protection against Leishmania (Viannia). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, I.A.; Cabelli, D.E. Superoxide dismutases-a review of the metal-associated mechanistic variations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plewes, K.A.; Barr, S.D.; Gedamu, L. Iron Superoxide Dismutases Targeted to the Glycosomes of Leishmania Chagasi Are Important for Survival. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 5910–5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, F.; Gedamu, L. Leishmania Donovani Iron Superoxide Dismutase A Is Targeted to the Mitochondria by Its N-Terminal Positively Charged Amino Acids. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2007, 154, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufernez, F.; Yernaux, C.; Gerbod, D.; Noël, C.; Chauvenet, M.; Wintjens, R.; Edgcomb, V.P.; Capron, M.; Opperdoes, F.R.; Viscogliosi, E. The Presence of Four Iron-Containing Superoxide Dismutase Isozymes in Trypanosomatidae: Characterization, Subcellular Localization, and Phylogenetic Origin in Trypanosoma Brucei. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 40, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayih, A.G.; Daifalla, N.S.; Gedamu, L. Immune Response and Protective Efficacy of a Heterologous DNA-Protein Immunization with Leishmania Superoxide Dismutase B1. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2145386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, B.L.S.; Silva, T.N.; Ribeiro, S.P.; Carvalho, K.I.L.; KallÁs, E.G.; Laurenti, M.D.; Passero, L.F.D. Analysis of Iron Superoxide Dismutase-encoding DNA Vaccine on the Evolution of the Leishmania amazonensis Experimental Infection. Parasite Immunol. 2015, 37, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffarifar, F.; Jorjani, O.; Sharifi, Z.; Dalimi, A.; Hassan, Z.M.; Tabatabaie, F.; Khoshzaban, F.; Hezarjaribi, H.Z. Enhancement of Immune Response Induced by DNA Vaccine Cocktail Expressing Complete LACK and TSA Genes against Leishmania Major. APMIS 2013, 121, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maspi, N.; Ghaffarifar, F.; Sharifi, Z.; Dalimi, A.; Khademi, S.Z. DNA Vaccination with a Plasmid Encoding LACK-TSA Fusion against Leishmania Major Infection in BALB/c Mice. Malays. J. Pathol. 2017, 39, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Campos-Neto, A.; Webb, J.R.; Greeson, K.; Coler, R.N.; Skeiky, Y.A.W.; Reed, S.G. Vaccination with Plasmid DNA Encoding TSA/LmSTI1 Leishmanial Fusion Proteins Confers Protection against Leishmania Major Infection in Susceptible BALB/c Mice. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 2828–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga, O.A.; Travi, B.L.; Park, W.; Perez, L.E.; Melby, P.C. Immunogenicity of a Multicomponent DNA Vaccine against Visceral Leishmaniasis in Dogs. Vaccine 2006, 24, 1928–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Freier, A.; Boussoffara, T.; Das, S.; Oswald, D.; Losch, F.O.; Selka, M.; Sacerdoti-Sierra, N.; Schönian, G.; Wiesmüller, K.-H.; et al. Modular Multiantigen T Cell Epitope–Enriched DNA Vaccine Against Human Leishmaniasis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cortés, A.; Ojeda, A.; López-Fuertes, L.; Timón, M.; Altet, L.; Solano-Gallego, L.; Sánchez-Robert, E.; Francino, O.; Alberola, J. Vaccination with Plasmid DNA Encoding KMPII, TRYP, LACK and GP63 Does Not Protect Dogs against Leishmania Infantum Experimental Challenge. Vaccine 2007, 25, 7962–7971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.R.; Campos-Neto, A.; Ovendale, P.J.; Martin, T.I.; Stromberg, E.J.; Badaro, R.; Reed, S.G. Human and Murine Immune Responses to a Novel Leishmania Major Recombinant Protein Encoded by Members of a Multicopy Gene Family. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 3279–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Y.; Bhatia, A.; Raman, V.S.; Liang, H.; Mohamath, R.; Picone, A.F.; Vidal, S.E.Z.; Vedvick, T.S.; Howard, R.F.; Reed, S.G. KSAC, the First Defined Polyprotein Vaccine Candidate for Visceral Leishmaniasis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Animal Model | Causative Agent | Key Features of VL Infection | Relevance to Human VL | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dog (Canis familiaris) | L. (L.) infantum | Natural domestic reservoir Infection mimics human VL clinical progression Symptoms: weight loss, anemia, lymphadenopathy, fever Skin lesions present (absent in humans) Parasites in spleen and skin even in asymptomatic dogs | Similar disease progression Important for epidemiology and experimental models Useful for vaccine and drug testing | High maintenance cost Ethical concerns Limited animal numbers per study | [23,24,25,26,27,30,35] |

| Mouse (mus musculus) | L. (L.) donovani and L. (L.) infantum | Subclinical and limited infection Effective cellular immune response Chronic fever, hepatosplenomegaly, cachexia absent Useful for studying protective immunity and genetic factors | Model for self-controlled or oligosymptomatic human cases Widely used due to availability of immunological tools | Does not fully reproduce human VL pathology | [36,37] |

| Golden hamster (mesocricetus auratus) | L. (L.) donovani | Highly susceptible to Leishmania Develops cachexia, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia Granulomas in liver, progressive spleen infection Failure to produce NO despite Th1 cytokine response - Ascites and renal complications rare in humans | Reproduces many human VL clinical and immunopathological features | Limited immunological reagents Some pathological features not typical of humans | [28,29,38,39] |

| Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) | L. (L.) infantum | Systemic disease similar to human VL Symptoms: fever, diarrhea, weight loss, anemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly Hepatic granuloma formation with epithelioid and Langhans giant cells Useful for vaccine and drug evaluation | High phylogenetic similarity Similar immune responses Mimics human infection | High cost and ethical issues Complex maintenance Some differences in disease control | [34] |

| Cebus apella monkey | L. (L.) infantum chagasi | Transient infection Effective cellular immune response controls parasite spread | Not recommended to mimic natural infection but useful to study resistance mechanisms | Does not adequately mimic human natural infection | [40] |

| Experimental Model | Causative Agent | Human Clinical Form(S) | Model Characteristics | Relevance to Human Disease | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOUSE (MUS MUSCULUS, BALB/C) | L. (L.) amazonensis | LCL MCL (rare) DCL | Progressive ulcerative lesions cutaneous metastasis Th2-type immune response associated with susceptibility | Mimics progressive disease in some human cases Useful for immunological studies | Limited chronic disease features | [46] |

| MOUSE (MUS MUSCULUS, C57BL/10, C57BL/6, DBA/2) | Chronic disease or subclinical infection depending on strain Eosinophil and mast cell infiltration. Th1 or Th2 immune responses | Mimics spectrum of human disease Allows study of genetic and immune response variability | Strain-dependent variability; some immune responses differ from humans | [47,48] | ||

| RHESUS MONKEYS (MACACA MULATTA) |

Progressive ulcerative lesions Lesions display mononuclear cell infiltrates composed of macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, along with tuberculoid-type granuloma formation There is a shift in circulating T cell subpopulations, initially a predominance of CD4+ T cells, followed by an increase in CD8+ T cells as the infection progresses |

Mimics progressive of the cutaneous leishmaniasis in humans Useful for immunological studies Useful to evaluate the efficacy of new vaccines |

High cost and ethical issues Complex maintenance Limited availability and sample sizes Longer experimental timelines | [49] | ||

| MOUSE (MUS MUSCULUS, BALB/C) | L. (V.) braziliensis |

LCL MCL | Transient or ulcerated lesions depending on inoculation site (hind footpad or ear) | Some infection features resemble human disease including lesion ulceration and parasite persistence | Resistance in many mouse strains; difficulty obtaining infectious stages | [42,51] |

| SAPAJUS APELLA MONKEYS |

Parasite persistence during infection Cutaneous lesions present |

Mimics human infection dynamics well. Useful for immunopathology and vaccine studies |

High cost and ethical issues Complex maintenance Limited availability and sample sizes Longer experimental timelines | [50] | ||

| MOUSE (MUS MUSCULUS, BALB/C) | L. (V.) panamensis |

LCL Rare mucosal involvement | Lower virulence observed in rodents |

Limited data Less commonly used models | Low virulence limits study of full disease spectrum | [43] |

| MOUSE (MUS MUSCULUS, BALB/C) | L. (V.) shawi | LCL |

Higher susceptibility with footpad swelling Severe inflammation Th1 response |

Represents natural infection in humans Useful for drug and vaccine development | Species-specific response; may not represent all human cases | [12] |

| Name | Vaccine Parasite | Adjuvant | Host | Route | Doses | Challenge | Protection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ld | L. donovani | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | Single dose | L. donovani | <50% less liver parasite burden | [120] | |

| Li | L. infantum | Dog | Subcutaneous | Single dose | L. infantum | 100% without Leishmania DNA; 97.8% without clinical signs | [115] | |

| Li HSP70-II−/− | L. infantum | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | Single dose | L. major | 90% less spleen parasite burden | [117] | |

| Lm | L. major | CpG | C57BL/6 | Intradermal | Single dose | 100% without lesion | [110] | |

| Lm | L. major | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | Single dose | L. major | 50% less skin parasite burden | [122] | |

| Lm Cen−/− | L. major | Hamster | Intradermal | Single dose | L. donovani | 90% less liver and spleen parasite burden | [118] | |

| Lm tkcd+/+ | L. major | C57BL/6 | Subcutaneous | Single dose | L. major | 90% spleen parasite burden; 100% without lesion | [116] | |

| Lt | L. tarentolae | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | Single dose | L. donovani | 80% spleen and liver parasite burden | [113] | |

| Lt | L. tarentolae | CpG | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | Single dose | L. major | 87% spleen parasite burden | [114] |

| Lt | L. tarentolae | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | Single dose | L. infantum | 90% spleen and liver parasite burden | [112] |

| Name | Vaccine Parasite | Adjuvant | Host | Route | Doses | Challenge | Protection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KBMA Li | L. infantum | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. infantum | 30% less liver parasite burden | [138] | |

| La | L. amazonensis | C57BL/6 | Intranasal | 2 doses | L. amazonensis | 50% less lesion size and parasite burden | [139] | |

| La | L. amazonensis | ADDAVAX® | C57BL/6 | Intranasal | 2 doses | L. amazonensis | Ineffective | [139] |

| La | L. amazonensis | Saponin | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. chagasi | 25% less liver parasite burden; 50% less spleen parasite burden | [128] |

| La-phVac and La-mtVac | L. amazonensis | C57BL/10 | Subcutaneous | 2 doses | L. amazonensis | 50% without lesion | [123] | |

| Lb | L. braziliensis | Saponin | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | Indeterminate | [129] | |

| Lb | L. braziliensis | Saponin | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. chagasi | 25% less liver parasite burden; 50% less spleen parasite burden | [128] |

| Lb-Sal | L. braziliensis | Saponin | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | Indeterminate | [130] | |

| Lc | L. chagasi | Saponin | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. chagasi | 90% less liver and spleen parasite burden | [140] |

| Ld | L. donovani | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. donovani | 15% less liver parasite burden; 24% less spleen parasite burden | [141] | |

| Ld | L. donovani | BCG | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. donovani | 30% less liver parasite burden; 40% less spleen parasite burden | [141] |

| Ld | L. donovani | MPL/TDM | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. donovani | 30% less liver parasite burden; 40% less spleen parasite burden | [141] |

| Ld-Lip | L. donovani | Cationic liposomes | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. donovani | 80% less liver parasite burden; 60% less spleen parasite burden | [141] | |

| Leishvacin® | L. amazonensis | Human | Intramuscular | 3 doses | L. panamensis | Indeterminate | [132] | |

| Li | L. infantum | BCG | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | Indeterminate | [142] | |

| Li | L. infantum | AdjuPrimeTM | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | Indeterminate | [142] | |

| Li | L. infantum | MPL/TDM/CWS | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | Indeterminate | [142] | |

| Lm | L.major | BCG | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. major | 50% less lesion size; 90% less skin parasite burden | [124] |

| Lm | L. major | Alum | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. major | 50% less lesion size; 70% less skin parasite burden | [124] |

| Lm | L.major | Montanide ISA 720 | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. major | 80% less lesion size; 90% less skin parasite burden | [124] |

| Lm | L.major | BCG | Human | Intradermal | Single dose | Indeterminate | [137] | |

| Lm | L. major | CpG | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. major | 50% less skin parasite burden | [122] |

| Lm(FKP) | L. major | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. major | 50% less lesion size; 30% less skin parasite burden | [124] | |

| sTLAVac | L. amazonensis | C57BL/6 | Subcutaneous | 2 doses | L. amazonensis | Indeterminate | [125] | |

| LsAmaAg | L. shawi | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 2 doses | L. shawi | Ineffective | [134] | |

| LsProAg | L. shawi | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 2 doses | L. shawi | 60% less lesion size; 70% less skin parasite burden | [134] | |

| WPV | L. amazonensis and L. braziliensis | BCG | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | Indeterminate | [131] |

| Name | Vaccine Parasite | Adjuvant | Host | Route | Doses | Challenge | Protection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LsPass1 | L. shawi | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 2 doses | L. shawi | Ineffective | [157] | |

| LsPass2 | L. shawi | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 2 doses | L. shawi | 50% less lesion size; 70% less skin parasite burden | [157] | |

| LsPass3 | L. shawi | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 2 doses | L. shawi | 75% less lesion size; 90% less skin parasite burden | [157] | |

| LiRic1 | L. infantum | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 4 doses | L. infantum | 50% less spleen parasite burden | [156] | |

| LiRic2 | L. infantum | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 4 doses | L. infantum | 66% less spleen parasite burden | [156] | |

| CaniLeish®/ESP | L. infantum | QA-21 | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | 92.7% healthy | [161] | |

| ChimeraT | Leishmania | Saponin | BALB/c | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. infantum | 80% less liver and spleen parasite burden; 90% less bone marrow and lymph node parasite burden | [155] |

| His6/LACK | L. braziliensis | CpG+Alumen | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. braziliensis | Ineffective | [177] |

| His6/LbSTI | L. braziliensis | CpG+Alumen | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. braziliensis | Ineffective | [177] |

| His6/LeIF | L. braziliensis | CpG+Alumen | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. braziliensis | Ineffective | [177] |

| His6/TSA, | L. braziliensis | CpG+Alumen | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. braziliensis | Ineffective | [177] |

| LaPSA-38S | L. amazonensis | In vitro | Indeterminate | [178] | ||||

| LaSP | L. amazonensis | Saponin | BALB/c | Intramuscular | 3 doses | L. amazonensis | Ineffective | [179] |

| Ld31 | L. donovani | Cationic liposomes | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. donovani | 70% less liver and spleen parasite burden | [152] |

| Ld51 | L. donovani | Cationic liposomes | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. donovani | 70% less liver and spleen parasite burden | [152] |

| Ld72 | L. donovani | Cationic liposomes | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. donovani | 60% less liver and spleen parasite burden | [152] |

| Ld78 | L. donovani | Cationic liposomes | BALB/c | 3 doses | L. donovani | 97% less liver parasite burden | [152] | |

| Ld79 | L. donovani | MPL | BALB/c | 3 doses | L. donovani | 96% less liver parasite burden | [153] | |

| Ld91 | L. donovani | Cationic liposomes | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. donovani | 40% less liver and spleen parasite burden | [152] |

| LdGP63 | L. donovani | Cationic liposomes | BALB/c | Intraperitoneal | 3 doses | L. donovani | 80% less liver and spleen parasite burden | [147] |

| LdPDI | L. donovani | Hamster | Intramuscular | 3 doses | L. donovani | 90% less spleen, liver and bone marrow parasite burden | [180] | |

| LdrA2 | L. donovani | Saponin | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | 43% no parasite burden detected; 72% asymptomatic | [178] | |

| LdTPI | L. donovani | Hamster | Intramuscular | 3 doses | L. donovani | ~90% less spleen and liver parasite burden | [181] | |

| Leish-111f(MML) or LEISH-F1 | Leishmania | CpG | C57BL/6 | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. major | 83% less lesion size; 45% less skin parasite burden | [158] |

| Leish-111f(MML) or LEISH-F1 | Leishmania | MPL-SE | Dog | Intradermal | 3 doses | L. infantum | 29% healthy | [146] |

| Leish-111f(MML) or LEISH-F1 | Leishmania | MPL-SE | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. infantum | Ineffective | [90] |

| Leish-111f(MML) or LEISH-F1 | Leishmania | Adjuprime | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | L. infantum | Ineffective | [90] |

| Leish-111f(MML) or LEISH-F1 | Leishmania | MPL-SE | Human | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | Indeterminate | [182] | |

| Leish-111f(MML) or LEISH-F1 | Leishmania | MPL-SE | Human | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | Indeterminate | [183] | |

| Leishmune® | L. donovani | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | 100% asymptomatic | [184] | ||

| Leishmune®/FML | L. donovani | Saponin | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | 89% healthy | [166] | |

| Leishmune®/FML | L. donovani | Saponin | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | 100% asymptomatic; 100% without Leishmania DNA | [162] | |

| Leishmune®/FML | L. donovani | Saponin | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | Indeterminate | [165] | |

| LeishTec®/rA2 | Leishmania | Saponin | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | 92% healthy | [166] | |

| LeishTec®/rA2 | Leishmania | Saponin | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | 69% healthy | [160] | |

| LeishTec®/rA2 | Leishmania | Saponin | Dog | Subcutaneous | 3 doses | 63.7% healthy | [167] | |

| LetiFend®/Q protein | L. infantum | Dog | Subcutaneous | Single dose | 95.3% healthy | [159] | ||

| Q protein | Leishmania | Dog | Subcutaneous | Single dose | 57% asymptomatic | [172] | ||

| Q protein | Leishmania | Dog | Subcutaneous | 2 doses | 28% asymptomatic | [172] | ||