Randomized Phase 3 Trial Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of V114, a 15-Valent PCV, Followed by PPSV23 6 Months Later (PNEU-DAY): Subgroup Analysis in Adults 18–49 Years of Age Enrolled at Center for Indigenous Health Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Vaccines and Administration

2.3. Study Assessments and Analyses

2.3.1. Safety and Immunogenicity

2.3.2. NP/OP Carriage of Vaccine-Preventable Serotypes

2.3.3. Detection and Serotyping of S. pneumoniae from NP/OP Analyses

3. Results

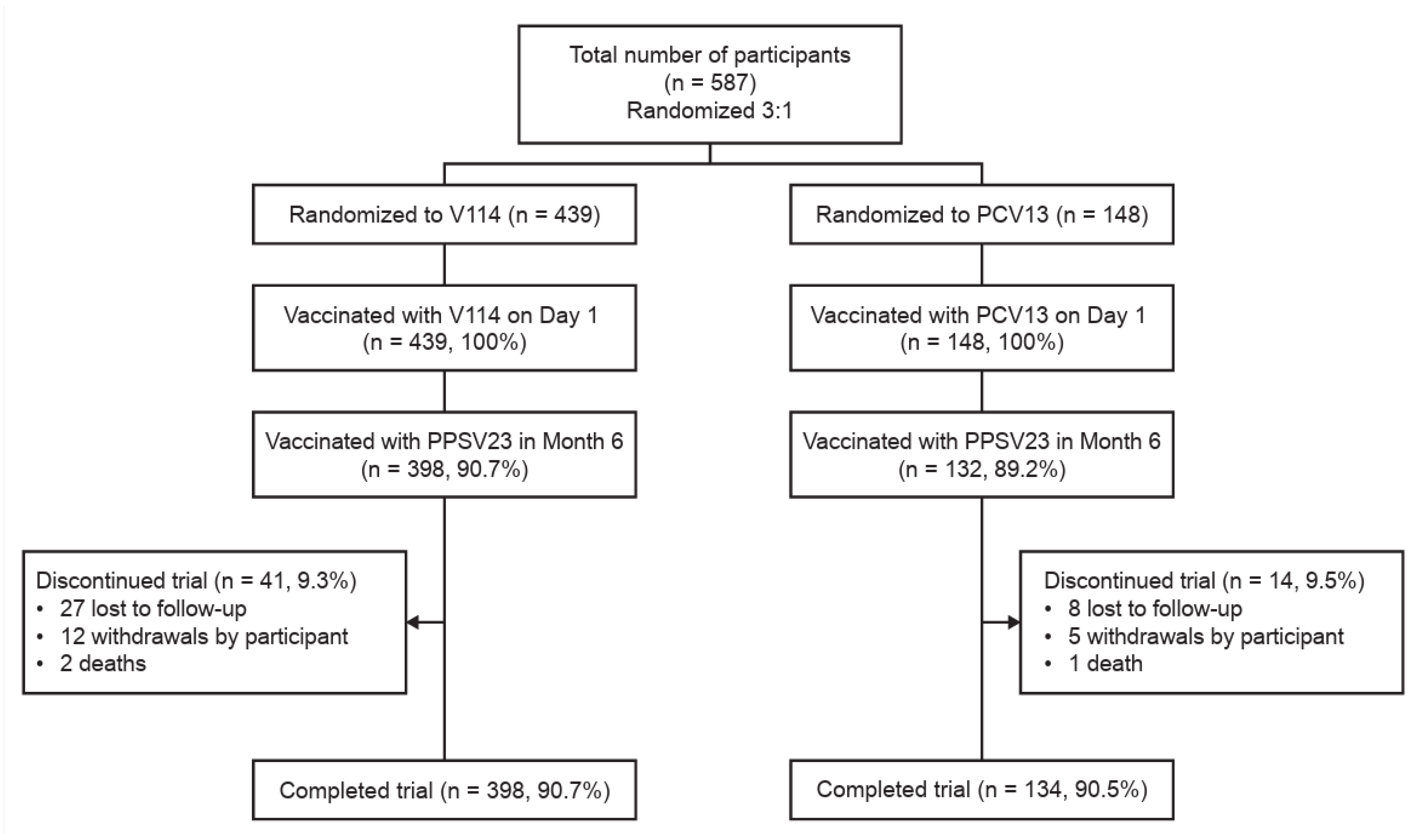

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Safety

3.2.1. Following Vaccination with PCV (Days 1–30)

3.2.2. Following Vaccination with PPSV23 (Months 6–7)

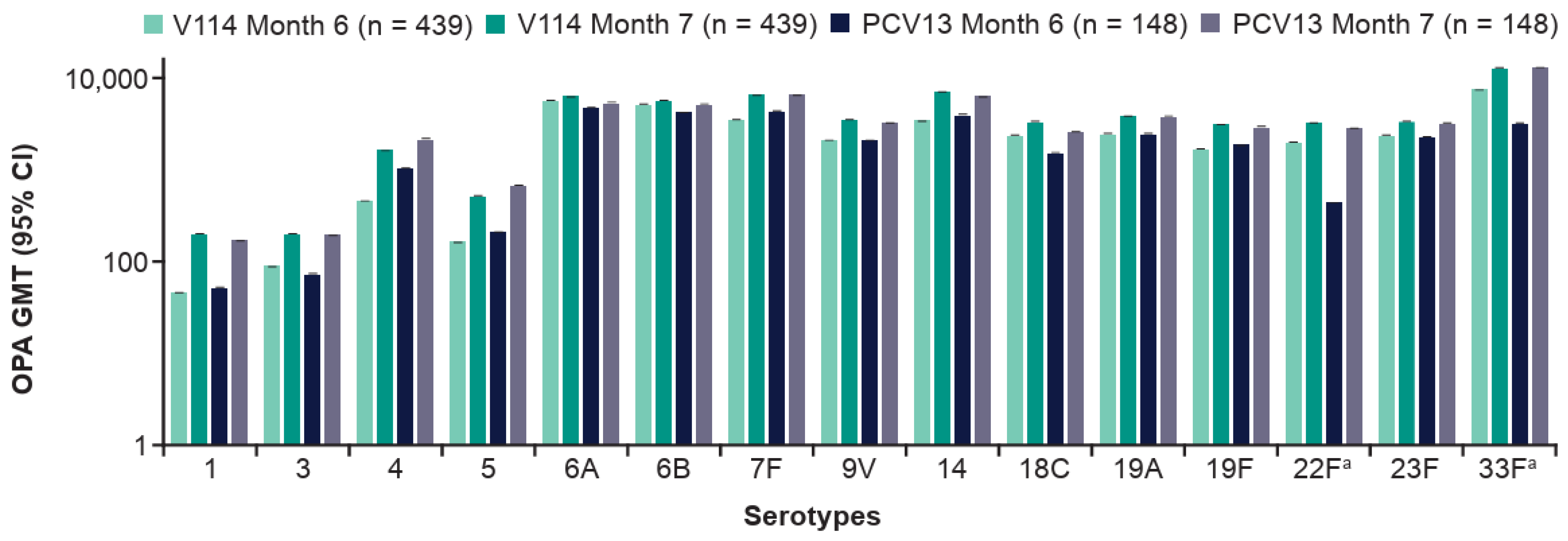

3.3. Immunogenicity

3.3.1. Following Vaccination with PCV (Days 1–30)

3.3.2. Following Vaccination with PPSV23 (Months 6–7)

3.4. NP/OP Carriage Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACIP | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices |

| AE | adverse event |

| AUDIT-C | Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test Alcohol Consumption |

| CIH | Johns Hopkins Center for Indigenous Health |

| cpsA | capsular polysaccharide synthesis gene A |

| GMC | geometric mean concentrations |

| GMT | geometric mean titers |

| IgG | immunoglobulin G |

| IPD | invasive pneumococcal disease |

| lytA | autolysin |

| MSD | Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA |

| NP | nasopharyngeal |

| OP | oropharyngeal |

| OPA | opsonophagocytic activity |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| PCV | pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

| PCV13 | 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

| PCV20 | 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

| PD | pneumococcal disease |

| piaA | pneumococcal iron acquisition |

| PPSV23 | 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine |

| SAE | serious adverse event |

| SSUAD | serotype-specific urinary antigen detection |

| V114 | 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine |

References

- GBD 2016 Lower Respiratory Infections Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1191–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1459–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drijkoningen, J.J.; Rohde, G.G. Pneumococcal infection in adults: Burden of disease. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. American Indian/Alaska Native Health Population Health Data. Available online: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/american-indianalaska-native-health (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Weatherholtz, R.; Millar, E.V.; Moulton, L.H.; Reid, R.; Rudolph, K.; Santosham, M.; O’Brien, K.L. Invasive pneumococcal disease a decade after pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use in an American Indian population at high risk for disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, J.P.; O’Brien, K.L.; Benin, A.L.; McCoy, S.I.; Donaldson, C.M.; Reid, R.; Schuchat, A.; Zell, E.R.; Hochman, M.; Santosham, M.; et al. Risk factors for invasive pneumococcal disease among Navajo adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 166, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, L.R.; Hammitt, L.L.; O’Brien, S.E.; Jacobs, M.R.; Donaldson, C.; Weatherholtz, R.C.; Reid, R.; Santosham, M.; O’Brien, K.L. Impact of the 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine on Pneumococcal Carriage Among American Indians. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2016, 35, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, E.F.G.; Chan, J.; Nguyen, C.D.; Russell, F.M. Factors associated with pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage: A systematic review. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0000327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, P.; McDonald, L.; Muus, K.; Knudson, A.; Wakefield, M.; Ludtke, R. Prevalence of Chronic Disease Among American Indian and Alaska Native Elders. Available online: https://www.nrcnaa.org/assets/6200-29399/chronic-disease-among-elders.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). CDC and Indian Country Working Together. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/44668/cdc_44668_DS1.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Groom, A.V.; Hennessy, T.W.; Singleton, R.J.; Butler, J.C.; Holve, S.; Cheek, J.E. Pneumonia and influenza mortality among American Indian and Alaska Native people, 1990–2009. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, S460–S469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M.G.; Bressler, S.S.; Apostolou, A.; Singleton, R.J. Lower respiratory tract infection hospitalizations among American Indian/Alaska Native adults, Indian Health Service and Alaska Region, 1998–2014. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 111, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, R.C.; Curns, A.T.; Singleton, R.J.; Sejvar, J.J.; Butler, J.C.; Paisano, E.L.; Schonberger, L.B.; Cheek, J.E. Infectious disease hospitalizations among older American Indian and Alaska Native adults. Public Health Rep. 2006, 121, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niederman, M.S.; Folaranmi, T.; Buchwald, U.K.; Musey, L.; Cripps, A.W.; Johnson, K.D. Efficacy and effectiveness of a 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine against invasive and noninvasive pneumococcal disease and related outcomes: A review of available evidence. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Leidner, A.J.; Gierke, R.; Farrar, J.L.; Morgan, R.L.; Campos-Outcalt, D.; Schechter, R.; Poehling, K.A.; Long, S.S.; Loehr, J.; et al. Use of 21-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine Among U.S. Adults: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2024. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Food and Drug Administration. PNEUMOVAX 23 Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/80547/download (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- World Health Organization. Vaccination Schedule for Pneumococcal Disease. Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/global/wiise-detail-page/vaccination-schedule-for-pneumococcal-disease?ISO_3_CODE=&TARGETPOP_GENERAL= (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Maeda, H.; Morimoto, K. Global distribution and characteristics of pneumococcal serotypes in adults. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2469424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matanock, A.; Lee, G.; Gierke, R.; Kobayashi, M.; Leidner, A.; Pilishvili, T. Use of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine and 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine Among Adults Aged >/=65 Years: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Food and Drug Administration. PREVNAR 13 (Pneumococcal 13-Valent Conjugate Vaccine [Diphtheria CRM197 Protein]) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM574852.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Scott, J.R.; Millar, E.V.; Lipsitch, M.; Moulton, L.H.; Weatherholtz, R.; Perilla, M.J.; Jackson, D.M.; Beall, B.; Craig, M.J.; Reid, R.; et al. Impact of more than a decade of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use on carriage and invasive potential in Native American communities. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 205, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Chen, C.L.; Su, L.H.; Chen, C.J.; Tsai, M.H.; Chiu, C.H. The microbiological characteristics and diagnosis of Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in the conjugate vaccine era. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2497611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozisik, L. The New Era of Pneumococcal Vaccination in Adults: What Is Next? Vaccines 2025, 13, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, K.; Masuda, S. Pneumococcal vaccines for prevention of adult pneumonia. Respir. Investig. 2025, 63, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Food and Drug Administration. VAXNEUVANCE™ (Pneumococcal 15-valent Conjugate Vaccine) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/vaxneuvance (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Moore, M.R.; Link-Gelles, R.; Schaffner, W.; Lynfield, R.; Lexau, C.; Bennett, N.M.; Petit, S.; Zansky, S.M.; Harrison, L.H.; Reingold, A.; et al. Effect of use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children on invasive pneumococcal disease in children and adults in the USA: Analysis of multisite, population-based surveillance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waight, P.A.; Andrews, N.J.; Ladhani, S.N.; Sheppard, C.L.; Slack, M.P.; Miller, E. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction: An observational cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tin Tin Htar, M.; Morato Martinez, J.; Theilacker, C.; Schmitt, H.J.; Swerdlow, D. Serotype evolution in Western Europe: Perspectives on invasive pneumococcal diseases (IPD). Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2019, 18, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Memari, N.; Teatero, S.; Athey, T.; Isabel, M.; Mazzulli, T.; Fittipaldi, N.; Gubbay, J.B. Whole-genome sequencing for surveillance of invasive pneumococcal diseases in Ontario, Canada: Rapid prediction of genotype, antibiotic resistance and characterization of emerging serotype 22F. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, A.R.; Adam, H.J.; Gilmour, M.W.; Baxter, M.R.; Martin, I.; Nichol, K.A.; Demczuk, W.H.; Hoban, D.J.; Zhanel, G.G. Assessment of multidrug resistance, clonality and virulence in non-PCV-13 Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes in Canada, 2011–2013. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1960–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, S.W.; Gladstone, R.A.; van Tonder, A.J.; Lees, J.A.; du Plessis, M.; Benisty, R.; Givon-Lavi, N.; Hawkins, P.A.; Cornick, J.E.; Kwambana-Adams, B.; et al. Pneumococcal lineages associated with serotype replacement and antibiotic resistance in childhood invasive pneumococcal disease in the post-PCV13 era: An international whole-genome sequencing study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Vaxneuvance: Summary of Product Characteristics. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/vaxneuvance-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Government of Canada. Pneumococcal Vaccine: Canadian Immunization Guide. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-16-pneumococcal-vaccine.html#a4 (accessed on 4 November 2024).

- Food and Drug Administration. CAPVAXIVE. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/capvaxive (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Health Canada. CAPVAXIVE® (Pneumococcal 21-Valent Conjugate Vaccine) Injection, for Intramuscular Use, Product Monograph. Available online: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00076331.PDF (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- PMDA; Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Capvaxive Intramuscular Syringe. Available online: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2025/P20250828001/170050000_30700AMX00129000_B100_1.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Government of Canada. CAPVAXIVE. Available online: https://dhpp.hpfb-dgpsa.ca/dhpp/resource/103871 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. CAPVAXIVE Pneumococcal 21-Valent Conjugate Vaccine 0.5mL Solution for Pre-filled Syringe. Available online: http://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/servlet/xmlmillr6?dbid=ebs/PublicHTML/pdfStore.nsf&docid=429290&agid=%28PrintDetailsPublic%29&actionid=1 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Prevnar 20 Package Insert. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/prevnar-20 (accessed on 8 April 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Pneumococcal Vaccine Recommendations. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/hcp/vaccine-recommendations/index.html (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. ACIP Recommendations. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/acip/vaccine-recommendations/index.html (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Hammitt, L.L.; Quinn, D.; Janczewska, E.; Pasquel, F.J.; Tytus, R.; Rajender Reddy, K.; Abarca, K.; Khaertynova, I.M.; Dagan, R.; McCauley, J.; et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and tolerability of V114, a 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, in immunocompetent adults aged 18–49 years with or without risk factors for pneumococcal disease: A randomized phase 3 trial (PNEU-DAY). Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofab605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinicaltrials.gov. A Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of V114 Followed by PNEUMOVAX™23 in Adults at Increased Risk for Pneumococcal Disease (V114-017/PNEU-DAY). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03547167 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Rumpf, H.J.; Hapke, U.; Meyer, C.; John, U. Screening for alcohol use disorders and at-risk drinking in the general population: Psychometric performance of three questionnaires. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002, 37, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajam, G.; Zhang, Y.; Antonello, J.M.; Grant-Klein, R.J.; Cook, L.; Panemangalore, R.; Pham, H.; Cooper, S.; Steinmetz, T.D.; Nguyen, J.; et al. Development and validation of a sensitive and robust multiplex antigen capture assay to quantify Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype-specific capsular polysaccharides in urine. mSphere 2022, 7, e0011422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, K.; Buchwald, U.K.; Hammitt, L.L.; LeBlanc, J.J.; Tso, C.; Riley, D.P.; VanDeRiet, D.; Weatherholtz, R.; Musey, L.; Shekar, T.; et al. The impact of pneumococcal vaccination and nasopharyngeal colonization on the performance of a serotype-specific urine antigen detection (SSUAD) assay. Vaccine 2025, 62, 127453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Streptococcus pneumoniae Detection and Serotyping Using PCR. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/strep-lab/php/pneumococcus/serotyping-using-pcr.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/streplab/pneumococcus/resources.html (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Trzcinski, K.; Bogaert, D.; Wyllie, A.; Chu, M.L.; van der Ende, A.; Bruin, J.P.; van den Dobbelsteen, G.; Veenhoven, R.H.; Sanders, E.A. Superiority of trans-oral over trans-nasal sampling in detecting Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization in adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, H.L.; Cardona, J.F.; Haranaka, M.; Schwartz, H.I.; Narejos Perez, S.; Dowell, A.; Chang, C.J.; Dagan, R.; Tamms, G.M.; Sterling, T.; et al. A phase 3 trial of safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of V114, 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, compared with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in adults 50 years of age and older (PNEU-AGE). Vaccine 2022, 40, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Invasive Pneumococcal Disease. Annual Epidemiological Report for 2018. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AER_for_2018_IPD.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Owusu-Edusei, K.; Deb, A.; Johnson, K.D. Estimates of the health and economic burden of pneumococcal infections attributable to the 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine serotypes in the USA. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11, 987–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, C.; Littlepage, S.; Yazzie, D.; Brasinikas, G.; Christensen, L.; Damon, S.; Denny, E.; Dixon , S.L.; Grant , L.R.; Harker-Jones., M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on invasive pneumococcal disease in American Indian communities in the Southwest US. J. Med. Microbiol. 2025, 74, 001983. [Google Scholar]

- Ul Haq, M.Z.; Irfan, H.; Shah, M.S.U.; Sumbal, A.; Mughal, S.; Ashraf, S.; Basaria, A.A.A.; Abdullah; Chacho, M.A.; Ayalew, B.D. Immunogenicity, safety and tolerability of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (V114) compared to 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13) in healthy infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine X 2025, 24, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsells, E.; Guillot, L.; Nair, H.; Kyaw, M.H. Serotype distribution of Streptococcus pneumoniae causing invasive disease in children in the post-PCV era: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, A.R.; Fear, T.; Baxter, M.; Adam, H.J.; Martin, I.; Demczuk, W.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Zhanel, G.G. Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Alliance. Invasive pneumococcal disease caused by serotypes 22F and 33F in Canada: The SAVE study 2011–2018. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 101, 115447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempere, J.; de Miguel, S.; Gonzalez-Camacho, F.; Yuste, J.; Domenech, M. Clinical Relevance and Molecular Pathogenesis of the Emerging Serotypes 22F and 33F of Streptococcus pneumoniae in Spain. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, R.N.; Gurtman, A.; Frenck, R.W.; Strout, C.; Jansen, K.U.; Trammel, J.; Scott, D.A.; Emini, E.A.; Gruber, W.C.; Schmoele-Thoma, B. Sequential administration of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in pneumococcal vaccine-naive adults 60–64 years of age. Vaccine 2014, 32, 2364–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A.; Gurtman, A.; van Cleeff, M.; Frenck, R.W.; Treanor, J.; Jansen, K.U.; Scott, D.A.; Emini, E.A.; Gruber, W.C.; Schmoele-Thoma, B. Influence of initial vaccination with 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine or 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine on anti-pneumococcal responses following subsequent pneumococcal vaccination in adults 50 years and older. Vaccine 2013, 31, 3594–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwald, U.K.; Andrews, C.P.; Ervin, J.; Peterson, J.T.; Tamms, G.M.; Krupa, D.; Ajiboye, P.; Roalfe, L.; Krick, A.L.; Sterling, T.M.; et al. Sequential administration of Prevnar 13 and PNEUMOVAX 23 in healthy participants 50 years of age and older. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 2678–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J.L.; Childs, L.; Ouattara, M.; Akhter, F.; Britton, A.; Pilishvili, T.; Kobayashi, M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy and effectiveness of pneumococcal vaccines in adults. Pathogens 2023, 12, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Norton, N.; Kaushik, P.; Brandtmuller, A.; Tsoumani, E. Recent changes to adult national immunization programs for pneumococcal vaccination in Europe and how they impact coverage: A systematic review of published and grey literature. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2279394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamprasertchai, T.; Ruenroengbun, N.; Kajeekul, R. Immunogenicity and safety of the higher-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine vs the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schellenberg, J.J.; Adam, H.J.; Baxter, M.R.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Golden, A.R.; Martin, I.; Demczuk, W.; Mulvey, M.R.; Zhanel, G.G. Comparison of PCV10, PCV13, PCV15, PCV20 and PPSV23 vaccine coverage of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae isolate serotypes in Canada: The SAVE study, 2011–2020. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, i37–i47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Bennett, N.M.; Gierke, R.; Almendares, O.; Moore, M.R.; Whitney, C.G.; Pilishvili, T. Intervals between PCV13 and PPSV23 vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 64, 944–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pera, A.; Campos, C.; Lopez, N.; Hassouneh, F.; Alonso, C.; Tarazona, R.; Solana, R. Immunosenescence: Implications for response to infection and vaccination in older people. Maturitas 2015, 82, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolich-Zugich, J. The twilight of immunity: Emerging concepts in aging of the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simell, B.; Auranen, K.; Kayhty, H.; Goldblatt, D.; Dagan, R.; O’Brien, K.L. Pneumococcal Carriage Group. The fundamental link between pneumococcal carriage and disease. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2012, 11, 841–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, N.; Tempia, S.; Cohen, C.; Madhi, S.A.; Venter, M.; Moyes, J.; Walaza, S.; Malope-Kgokong, B.; Groome, M.; du Plessis, M.; et al. High nasopharyngeal pneumococcal density, increased by viral coinfection, is associated with invasive pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miellet, W.R.; Almeida, S.T.; Trzcinski, K.; Sa-Leao, R. Streptococcus pneumoniae carriage studies in adults: Importance, challenges, and key issues to consider when using quantitative PCR-based approaches. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1122276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlepage, S.J.; Grant, L.R.; Vidal, J.E.; Jacobs, M.R.; Weatherholtz, R.C.; Alexander-Parrish, R.; Colelay, J.; Charley, M.; Cutler, M.; Good, C.E.; et al. Differences in pneumococcal carriage prevalence by testing method and specimen type among Native American individuals during routine use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13). Poster #117. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Pneumococci & Pneumococcal Diseases (ISPPD-12), Toronto, ON, Canada, 19–23 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Simoes, A.S.; Tavares, D.A.; Rolo, D.; Ardanuy, C.; Goossens, H.; Henriques-Normark, B.; Linares, J.; de Lencastre, H.; Sa-Leao, R. lytA-based identification methods can misidentify Streptococcus pneumoniae. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2016, 85, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewhirst, F.E.; Chen, T.; Izard, J.; Paster, B.J.; Tanner, A.C.; Yu, W.H.; Lakshmanan, A.; Wade, W.G. The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 5002–5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abranches, J.; Zeng, L.; Kajfasz, J.K.; Palmer, S.R.; Chakraborty, B.; Wen, Z.T.; Richards, V.P.; Brady, L.J.; Lemos, J.A. Biology of oral streptococci. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryskier, A. Viridans group streptococci: A reservoir of resistant bacteria in oral cavities. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2002, 8, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navajo Epidemiology Center. Serotype 4 Invasive Pneumococcal Disease (IPD) Information for Providers. Active Bacterial Surveillance Alert—March 2024. Available online: https://nec.navajo-nsn.gov/Portals/0/Reports/ST4%20alert%20for%20NN%20providers_2024.0312.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

| n (%) | V114 | PCV13 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccinated participants | 439 (100) | 148 (100) | 587 (100) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 258 (58.8) | 81 (54.7) | 339 (57.8) |

| Male | 181 (41.2) | 67 (45.3) | 248 (42.2) |

| Age, years | |||

| 18–29 | 179 (40.8) | 64 (43.2) | 243 (41.4) |

| 30–39 | 161 (36.7) | 48 (32.4) | 209 (35.6) |

| 40–49 | 99 (22.6) | 36 (24.3) | 135 (23.0) |

| Mean | 32.7 | 32.1 | 32.6 |

| Range | 19–49 | 18–49 | 18–49 |

| Race | |||

| American Indian | 439 (100) | 148 (100) | 587 (100) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 422 (96.1) | 137 (92.6) | 559 (95.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 17 (3.9) | 11 (7.4) | 28 (4.8) |

| Participants by risk factors a | |||

| No risk factors | 285 (64.9) | 96 (64.9) | 381 (64.9) |

| with ≥1 risk factors | 154 (35.1) | 52 (35.1) | 206 (35.1) |

| n (%) | Following Vaccination with V114/PCV13 (Day 1–Month 6) | Following Vaccination with PPSV23 (Month 6–Month 7) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V114 n = 439 | PCV13 n = 148 | V114 n = 398 | PCV13 n = 132 | |

| Unsolicited or solicited AEs | ||||

| Any AE | 356 (81.1) | 114 (77.0) | 250 (62.8) | 85 (64.4) |

| Injection-site a | 324 (73.8) | 98 (66.2) | 225 (56.5) | 78 (59.1) |

| Systemic | 246 (56.0) | 91 (61.5) | 157 (39.4) | 54 (40.9) |

| Any vaccine-related AE b | 335 (76.3) | 105 (70.9) | 237 (59.5) | 80 (60.6) |

| Systemic | 193 (44.0) | 65 (43.9) | 125 (31.4) | 45 (34.1) |

| Any SAE | 25 (5.7) | 8 (5.4) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.8) |

| Any vaccine-related SAE b | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Deaths | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Solicited AEs | ||||

| Solicited injection-site AEs c | 323 (73.6) | 98 (66.2) | 225 (56.5) | 78 (59.1) |

| Injection-site pain | 316 (72.0) | 96 (64.9) | 219 (55.0) | 74 (56.1) |

| Injection-site swelling | 102 (23.2) | 31 (20.9) | 71 (17.8) | 25 (18.9) |

| Injection-site erythema | 60 (13.7) | 17 (11.5) | 53 (13.3) | 22 (16.7) |

| Solicited systemic AEs d | 212 (48.3) | 77 (52.0) | 141 (35.4) | 50 (37.9) |

| Fatigue | 146 (33.3) | 56 (37.8) | 99 (24.9) | 31 (23.5) |

| Headache | 105 (23.9) | 40 (27.0) | 68 (17.1) | 26 (19.7) |

| Myalgia | 111 (25.3) | 38 (25.7) | 56 (14.1) | 20 (15.2) |

| Arthralgia | 69 (15.7) | 20 (13.5) | 44 (11.1) | 17 (12.9) |

| Pneumococcal Carriage Prevalence, % (n/N) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit | V114 | PCV13 | Total |

| Day 1 | 23.9 (54/226) | 18.7 (14/75) | 22.6 (68/301) |

| Day 3 | 22.4 (47/210) | 15.5 (11/71) | 20.6 (58/281) |

| Day 8 | 20.7 (42/203) | 16.7 (11/66) | 19.7 (53/269) |

| Day 15 | 20.2 (42/208) | 9.0 (6/67) | 17.5 (48/275) |

| Day 30 | 18.6 (41/220) | 10.3 (7/68) | 16.7 (48/288) |

| Month 6 | 18.6 (37/199) | 20.3 (13/64) | 19.0 (50/263) |

| Day 183 | 18.0 (34/189) | 15.3 (9/59) | 17.3 (43/248) |

| Day 188 | 17.8 (33/185) | 19.3 (11/57) | 18.2 (44/242) |

| Day 195 | 20.4 (39/191) | 10.9 (6/55) | 18.3 (45/246) |

| Month 7 | 20.7 (42/203) | 11.3 (7/62) | 18.5 (49/265) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hammitt, L.L.; Buchwald, U.K.; McCauley, J.; Shekar, T.; Fu, W.; Cheon, K.; Sterling, T.; Tamms, G.; Banniettis, N.; Musey, L.; et al. Randomized Phase 3 Trial Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of V114, a 15-Valent PCV, Followed by PPSV23 6 Months Later (PNEU-DAY): Subgroup Analysis in Adults 18–49 Years of Age Enrolled at Center for Indigenous Health Sites. Vaccines 2026, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010003

Hammitt LL, Buchwald UK, McCauley J, Shekar T, Fu W, Cheon K, Sterling T, Tamms G, Banniettis N, Musey L, et al. Randomized Phase 3 Trial Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of V114, a 15-Valent PCV, Followed by PPSV23 6 Months Later (PNEU-DAY): Subgroup Analysis in Adults 18–49 Years of Age Enrolled at Center for Indigenous Health Sites. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleHammitt, Laura L., Ulrike K. Buchwald, Jennifer McCauley, Tulin Shekar, Wei Fu, Kyeongmi Cheon, Tina Sterling, Gretchen Tamms, Natalie Banniettis, Luwy Musey, and et al. 2026. "Randomized Phase 3 Trial Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of V114, a 15-Valent PCV, Followed by PPSV23 6 Months Later (PNEU-DAY): Subgroup Analysis in Adults 18–49 Years of Age Enrolled at Center for Indigenous Health Sites" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010003

APA StyleHammitt, L. L., Buchwald, U. K., McCauley, J., Shekar, T., Fu, W., Cheon, K., Sterling, T., Tamms, G., Banniettis, N., Musey, L., LeBlanc, J. J., Weatherholtz, R., Riley, D. P., Denny, E., Tso, C., Roessler, K., & Santosham, M. (2026). Randomized Phase 3 Trial Evaluating the Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of V114, a 15-Valent PCV, Followed by PPSV23 6 Months Later (PNEU-DAY): Subgroup Analysis in Adults 18–49 Years of Age Enrolled at Center for Indigenous Health Sites. Vaccines, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010003