A Comparison of Flow Cytometry-based versus ImmunoSpot- or Supernatant-based Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-specific Memory B Cells in Peripheral Blood

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Human Donors

2.2. Recombinant Proteins

2.3. Polyclonal B Cell Stimulation

2.4. ELISA

2.5. B Cell ELISPOT Assays

2.6. ImmunoSpot® Image Acquisition and SFU Counting

2.7. Flow Cytometry Staining Procedure

2.8. Statistical Methods

3. Results

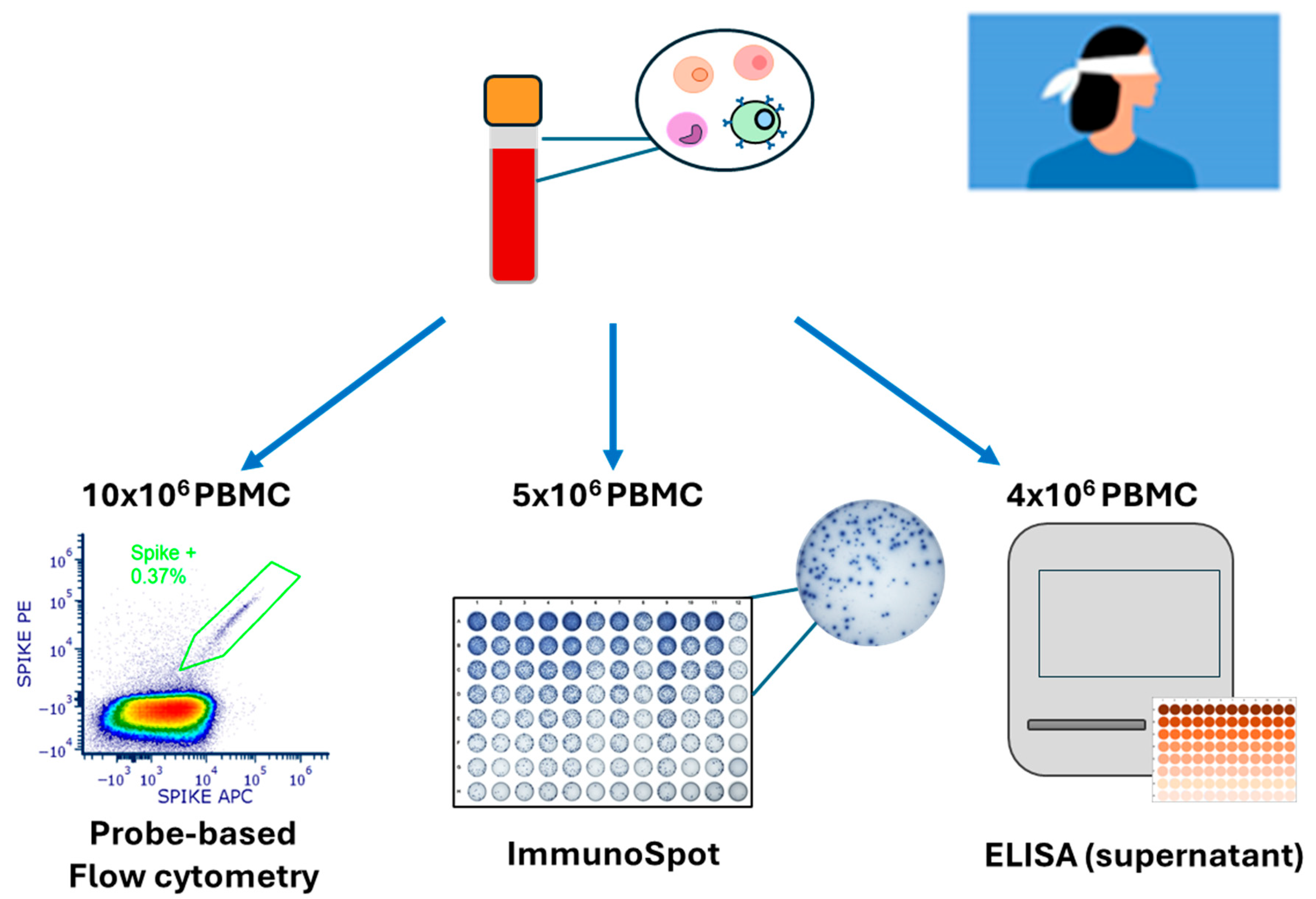

3.1. Rationale and Study Design

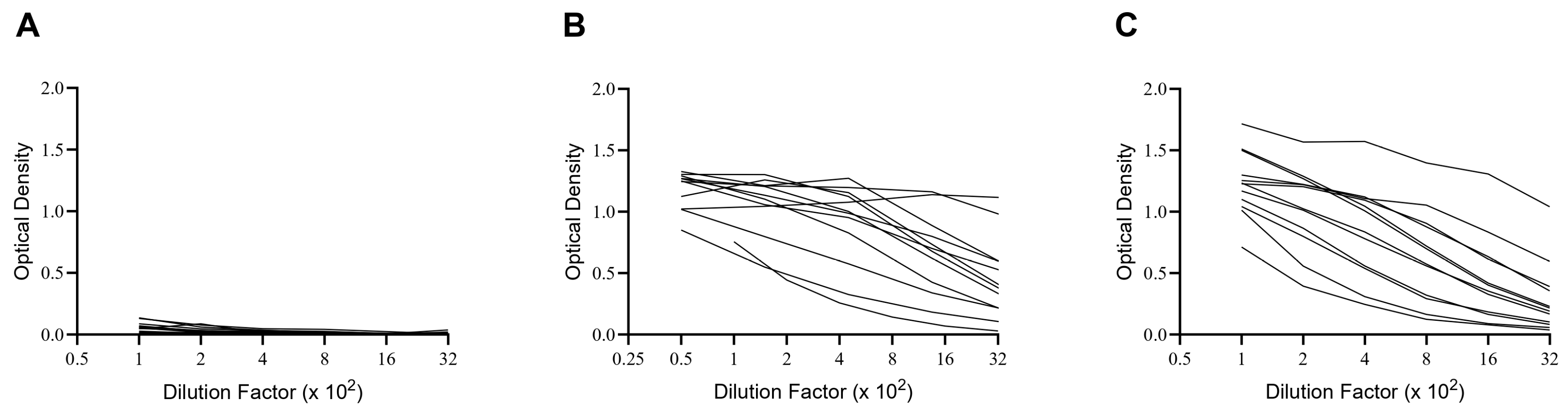

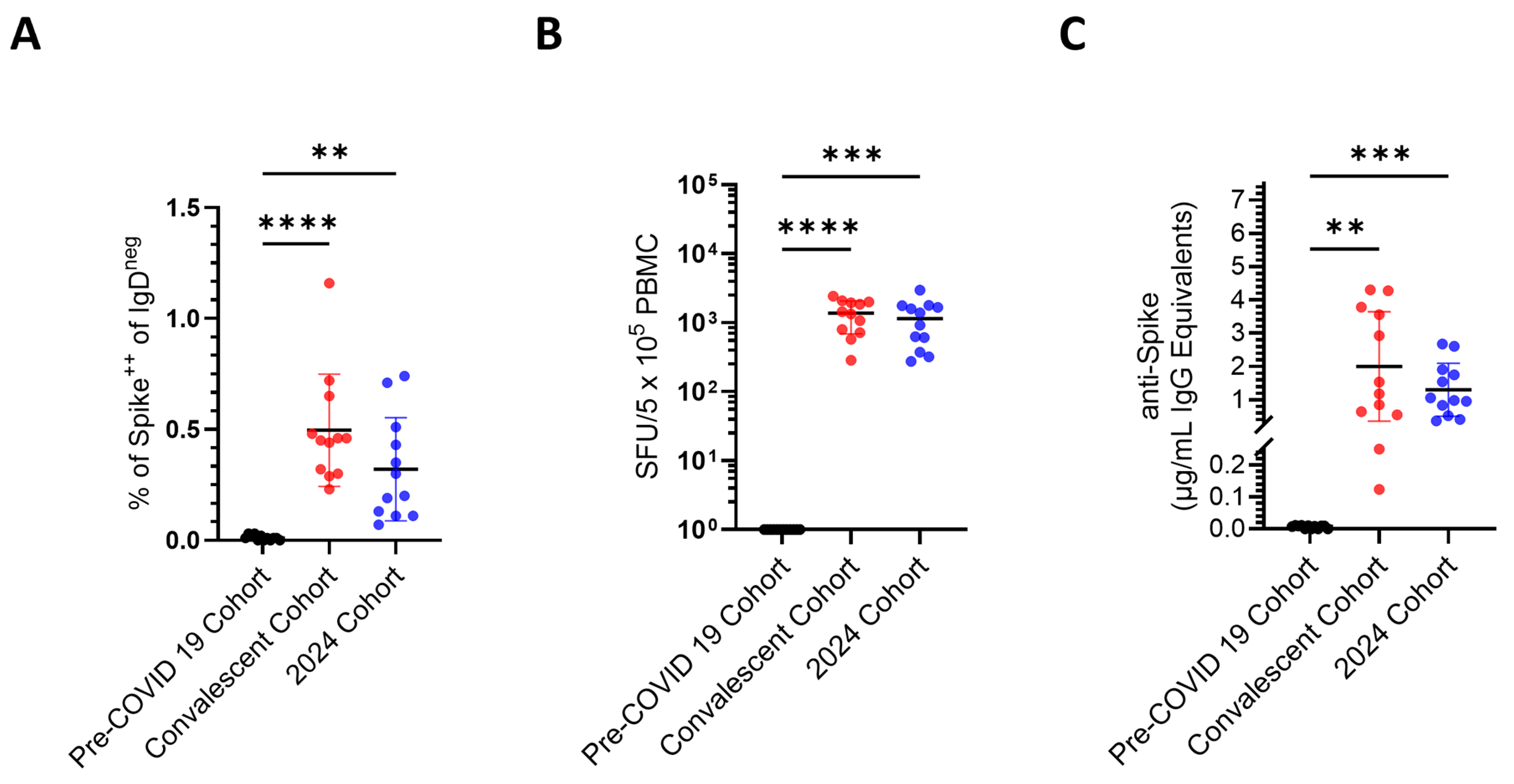

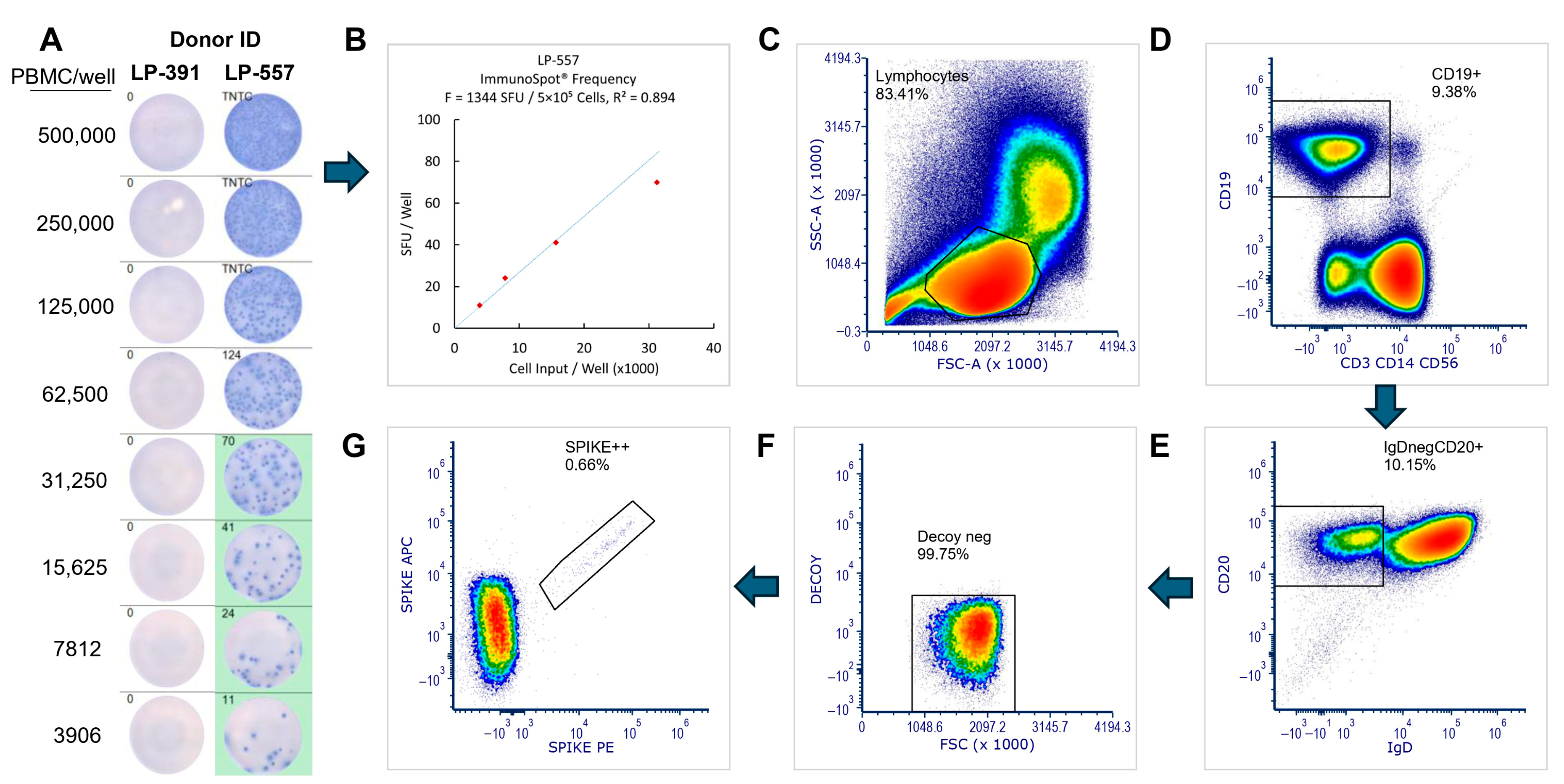

3.2. Comparison of Sensitivity, Specificity, and False Negative Results Using Three Different Techniques for Bmem Detection

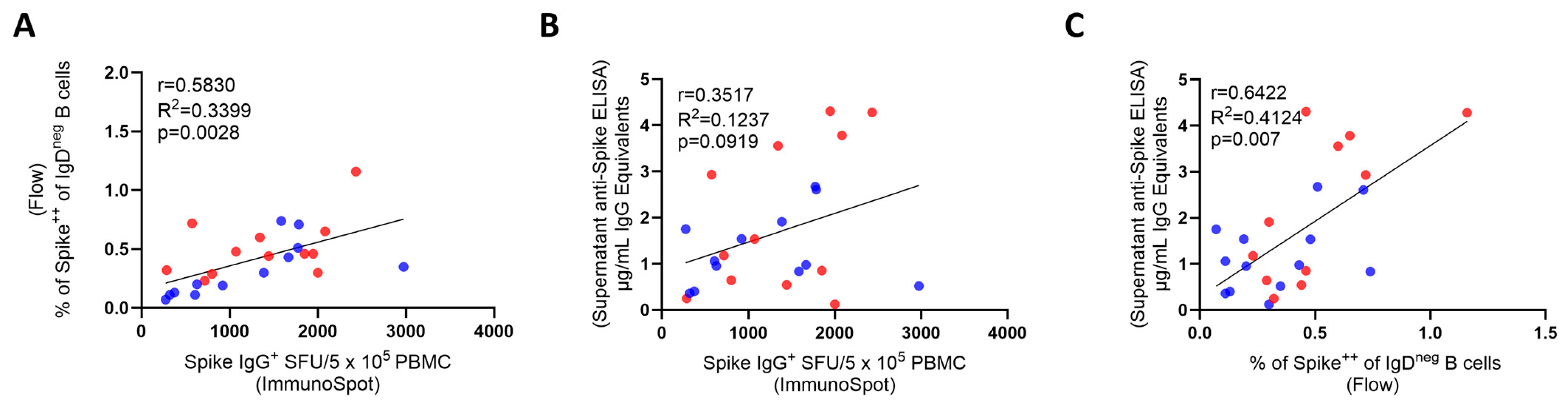

3.3. Inter-Bmem Assay Correlations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Bmem | memory B cell(s) |

| PBMCs | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| ASC | antibody-secreting cells |

References

- Breiteneder, H.; Peng, Y.Q.; Agache, I.; Diamant, Z.; Eiwegger, T.; Fokkens, W.J.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Nadeau, K.; O’HEhir, R.E.; O’MAhony, L.; et al. Biomarkers for diagnosis and prediction of therapy responses in allergic diseases and asthma. Allergy 2020, 75, 3039–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendeiro, A.F.; Vorkas, C.K.; Krumsiek, J.; Singh, H.K.; Kapadia, S.N.; Cappelli, L.V.; Cacciapuoti, M.T.; Inghirami, G.; Elemento, O.; Salvatore, M. Metabolic and Immune Markers for Precise Monitoring of COVID-19 Severity and Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 809937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South, A.M.; Grimm, P.C. Transplant immuno-diagnostics: Crossmatch and antigen detection. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2016, 31, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stylianou, G.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V.; Pearce, S.; Todryk, S. Measuring Human Memory B Cells in Autoimmunity Using Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSpot. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettelli, F.; Vallerini, D.; Lagreca, I.; Barozzi, P.; Riva, G.; Nasillo, V.; Paolini, A.; D’Amico, R.; Forghieri, F.; Morselli, M.; et al. Identification and validation of diagnostic cut-offs of the ELISpot assay for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in high-risk patients. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreto-Binaghi, L.E.; Nieto-Ponce, M.; Palencia-Reyes, A.; Chavez-Dominguez, R.L.; Blancas-Zaragoza, J.; Franco-Mendoza, P.; Garcia-Ramos, M.A.; Hernandez-Lazaro, C.I.; Torres, M.; Carranza, C. Validation of the Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSpot Analytic Method for the Detection of Human IFN-gamma from Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells in Response to the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapporto, F.; De Tommaso, D.; Marrocco, C.; Piu, P.; Semplici, C.; Fantoni, G.; Ferrigno, I.; Piccini, G.; Monti, M.; Vanni, F.; et al. Validation of a double-color ELISpot assay of IFN-gamma and IL-4 production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J. Immunol. Methods 2024, 524, 113588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantet-Blaudez, F.; Ruiz, J.; Gautheron, S.; Pagnon, A. Evaluation of the viability and functionality of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells cryopreserved up to 2 years in animal-protein-free freezing media compared to the FBS-supplemented reference medium. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1627973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, J.R.; Wilson, K.L.; Fialho, J.; Goodchild, G.; Prakash, M.D.; McLeod, C.; Richmond, P.C.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Flanagan, K.L.; Plebanski, M. Optimisation of the cultured ELISpot/Fluorospot technique for the selective investigation of SARS-CoV-2 reactive central memory T cells. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1547220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, N.; Behrends, U.; Hapfelmeier, A.; Protzer, U.; Bauer, T. Validation of an IFNgamma/IL2 FluoroSpot assay for clinical trial monitoring. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauthe, A.; Cedrone, E.; Villar-Hernandez, R.; Rusch, E.; Springer, M.; Schuster, M.; Preyer, R.; Dobrovolskaia, M.A.; Gutekunst, M. IFN-gamma/IL-2 Double-Color FluoroSpot Assay for Monitoring Human Primary T Cell Activation: Validation, Inter-Laboratory Comparison, and Recommendations for Clinical Studies. AAPS J. 2025, 27, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waerlop, G.; Leroux-Roels, G.; Pagnon, A.; Begue, S.; Salaun, B.; Janssens, M.; Medaglini, D.; Pettini, E.; Montomoli, E.; Gianchecchi, E.; et al. Proficiency tests to evaluate the impact on assay outcomes of harmonized influenza-specific Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS) and IFN-ɣ Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSpot (ELISpot) protocols. J. Immunol. Methods 2023, 523, 113584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winklmeier, S.; Eisenhut, K.; Taskin, D.; Rubsamen, H.; Gerhards, R.; Schneider, C.; Wratil, P.R.; Stern, M.; Eichhorn, P.; Keppler, O.T.; et al. Persistence of functional memory B cells recognizing SARS-CoV-2 variants despite loss of specific IgG. iScience 2022, 25, 103659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, C.; Koppert, S.; Becza, N.; Kuerten, S.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V. Antibody Levels Poorly Reflect on the Frequency of Memory B Cells Generated following SARS-CoV-2, Seasonal Influenza, or EBV Infection. Cells 2022, 11, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Kurosaki, T. Memory B cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeda, M.Z.; Hong, T.; Huang, C.; Huang, W.; Mu, Q. B cell memory: From generation to reactivation: A multipronged defense wall against pathogens. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, M.; Kwak, K.; Pierce, S.K. B cell memory: Building two walls of protection against pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightman, S.M.; Utley, A.; Lee, K.P. Survival of Long-Lived Plasma Cells (LLPC): Piecing Together the Puzzle. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, A.E.; Henry, C. Remembrance of Things Past: Long-Term B Cell Memory After Infection and Vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, A.; Terry, W.D.; Waldmann, T.A. Metabolic properties of IgG subclasses in man. J. Clin. Investig. 1970, 49, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, R.A.; Hauser, A.E.; Hiepe, F.; Radbruch, A. Maintenance of serum antibody levels. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 23, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P.; Zeng, C.; Carlin, C.; Lozanski, G.; Saif, L.J.; Oltz, E.M.; Gumina, R.J.; Liu, S.L. Neutralizing antibody responses elicited by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination wane over time and are boosted by breakthrough infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabn8057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, D.H.; Minn, D.; Lim, J.; Lee, K.D.; Kang, Y.M.; Choe, K.W.; Kim, K.N. Rapidly Declining SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Titers within 4 Months after BNT162b2 Vaccination. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, E.G.; Lustig, Y.; Cohen, C.; Fluss, R.; Indenbaum, V.; Amit, S.; Doolman, R.; Asraf, K.; Mendelson, E.; Ziv, A.; et al. Waning Immune Humoral Response to BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine over 6 Months. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, J.; Graham, C.; Merrick, B.; Acors, S.; Pickering, S.; Steel, K.J.A.; Hemmings, O.; O’Byrne, A.; Kouphou, N.; Galao, R.P.; et al. Longitudinal observation and decline of neutralizing antibody responses in the three months following SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Pawelec, G.; Lehmann, P.V. The Importance of Monitoring Antigen-Specific Memory B Cells, and How ImmunoSpot Assays Are Suitable for This Task. Cells 2025, 14, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becza, N.; Yao, L.; Lehmann, P.V.; Kirchenbaum, G.A. Optimizing PBMC Cryopreservation and Utilization for ImmunoSpot((R)) Analysis of Antigen-Specific Memory B Cells. Vaccines 2025, 13, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, P.V.; Karulin, A.Y.; Becza, N.; Yao, L.; Liu, Z.; Chepke, J.; Maul-Pavicic, A.; Wolf, C.; Koppert, S.; Valente, A.V.; et al. Theoretical and practical considerations for validating antigen-specific B cell ImmunoSpot assays. J. Immunol. Methods 2025, 537, 113817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonyaratanakornkit, J.; Taylor, J.J. Techniques to Study Antigen-Specific B Cell Responses. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozhkova, M.; Gardzheva, P.; Rangelova, V.; Taskov, H.; Murdjeva, M. Cutting-edge assessment techniques for B cell immune memory: An overview. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2024, 38, 2345119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A.; Crowe, J.E., Jr. Use of Human Hybridoma Technology To Isolate Human Monoclonal Antibodies. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantin, R.F.; Clark, J.J.; Cohn, H.; Jaiswal, D.; Bozarth, B.; Rao, V.; Civljak, A.; Lobo, I.; Nardulli, J.R.; Srivastava, K.; et al. Mapping of human monoclonal antibody responses to XBB.1.5 COVID-19 monovalent vaccines: A B cell analysis. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, A.; Pazos-Castro, D.; Urselli, F.; Grydziuszko, E.; Mann-Delany, O.; Fang, A.; Walker, T.D.; Guruge, R.T.; Tome-Amat, J.; Diaz-Perales, A.; et al. Production and use of antigen tetramers to study antigen-specific B cells. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 727–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinna, D.; Corti, D.; Jarrossay, D.; Sallusto, F.; Lanzavecchia, A. Clonal dissection of the human memory B-cell repertoire following infection and vaccination. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 1260–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astakhova, E.A.; Byazrova, M.G.; Yusubalieva, G.M.; Kulemzin, S.V.; Kruglova, N.A.; Prilipov, A.G.; Baklaushev, V.P.; Gorchakov, A.A.; Taranin, A.V.; Filatov, A.V. Functional Profiling of In Vitro Reactivated Memory B Cells Following Natural SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Gam-COVID-Vac Vaccination. Cells 2022, 11, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Becza, N.; Maul-Pavicic, A.; Chepke, J.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V. Four-Color ImmunoSpot((R)) Assays Requiring Only 1–3 mL of Blood Permit Precise Frequency Measurements of Antigen-Specific B Cells-Secreting Immunoglobulins of All Four Classes and Subclasses. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2768, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holshue, M.L.; DeBolt, C.; Lindquist, S.; Lofy, K.H.; Wiesman, J.; Bruce, H.; Spitters, C.; Ericson, K.; Wilkerson, S.; Tural, A.; et al. First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.L.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Schaub, J.M.; DiVenere, A.M.; Kuo, H.C.; Javanmardi, K.; Le, K.C.; Wrapp, D.; Lee, A.G.; Liu, Y.; et al. Structure-based Design of Prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spikes. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, R.B.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Clutter, E.F.; Sautto, G.A.; Ross, T.M. Preexisting subtype immunodominance shapes memory B cell recall response to influenza vaccination. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e132155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Becza, N.; Stylianou, G.; Tary-Lehmann, M.; Todryk, S.M.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V. SARS-CoV-2 Infection or COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination Elicits Partially Different Spike-Reactive Memory B Cell Responses in Naive Individuals. Vaccines 2025, 13, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppert, S.; Wolf, C.; Becza, N.; Sautto, G.A.; Franke, F.; Kuerten, S.; Ross, T.M.; Lehmann, P.V.; Kirchenbaum, G.A. Affinity Tag Coating Enables Reliable Detection of Antigen-Specific B Cells in Immunospot Assays. Cells 2021, 10, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karulin, A.Y.; Katona, M.; Megyesi, Z.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V. Artificial Intelligence-Based Counting Algorithm Enables Accurate and Detailed Analysis of the Broad Spectrum of Spot Morphologies Observed in Antigen-Specific B-Cell ELISPOT and FluoroSpot Assays. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2768, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weskamm, L.M.; Dahlke, C.; Addo, M.M. Flow cytometric protocol to characterize human memory B cells directed against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein antigens. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorkander, S.; Du, L.; Zuo, F.; Ekstrom, S.; Wang, Y.; Wan, H.; Sherina, N.; Schoutens, L.; Andrell, J.; Andersson, N.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific B- and T-cell immunity in a population-based study of young Swedish adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 65–75.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafizoglu, M.; Bas, A.O.; Tavukcuoglu, E.; Sahiner, Z.; Oytun, M.G.; Uluturk, S.; Yanik, H.; Dogu, B.B.; Cankurtaran, M.; Esendagli, G.; et al. Memory T cell responses in seronegative older adults following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Clin. Immunol. Commun. 2022, 2, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terlutter, F.; Caspell, R.; Nowacki, T.M.; Lehmann, A.; Li, R.; Zhang, T.; Przybyla, A.; Kuerten, S.; Lehmann, P.V. Direct Detection of T- and B-Memory Lymphocytes by ImmunoSpot(R) Assays Reveals HCMV Exposure that Serum Antibodies Fail to Identify. Cells 2018, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, J.M.; Mateus, J.; Kato, Y.; Hastie, K.M.; Yu, E.D.; Faliti, C.E.; Grifoni, A.; Ramirez, S.I.; Haupt, S.; Frazier, A.; et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 2021, 371, eabf4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cohort | Pre-COVID-19 Donors | Convalescent Donors | 2024 Donors |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Age | 36.58 (SD 10.93) | 47.58 (SD 9.376) | 41.33 (SD 7.075) |

| Collection date (start to end) | Apr-2017 to Oct-2019 | Jul-2020 to Dec-2020 | Feb-2024 to June-2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stylianou, G.; Cookson, S.; Nassif, J.T.; Kirchenbaum, G.A.; Lehmann, P.V.; Todryk, S.M. A Comparison of Flow Cytometry-based versus ImmunoSpot- or Supernatant-based Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-specific Memory B Cells in Peripheral Blood. Vaccines 2026, 14, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010020

Stylianou G, Cookson S, Nassif JT, Kirchenbaum GA, Lehmann PV, Todryk SM. A Comparison of Flow Cytometry-based versus ImmunoSpot- or Supernatant-based Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-specific Memory B Cells in Peripheral Blood. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleStylianou, Georgia, Sharon Cookson, Justin T. Nassif, Greg A. Kirchenbaum, Paul V. Lehmann, and Stephen M. Todryk. 2026. "A Comparison of Flow Cytometry-based versus ImmunoSpot- or Supernatant-based Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-specific Memory B Cells in Peripheral Blood" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010020

APA StyleStylianou, G., Cookson, S., Nassif, J. T., Kirchenbaum, G. A., Lehmann, P. V., & Todryk, S. M. (2026). A Comparison of Flow Cytometry-based versus ImmunoSpot- or Supernatant-based Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Spike-specific Memory B Cells in Peripheral Blood. Vaccines, 14(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010020