Changed Trends in Utilization and Substitution Pattern of Non-National Immunization Program Vaccines in Central China, 2011–2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Non-NIP Vaccine Categories

2.3. Substitutions with Non-NIP Vaccines

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overall Utilization of Non-National Immunization Program (Non-NIP) Vaccines

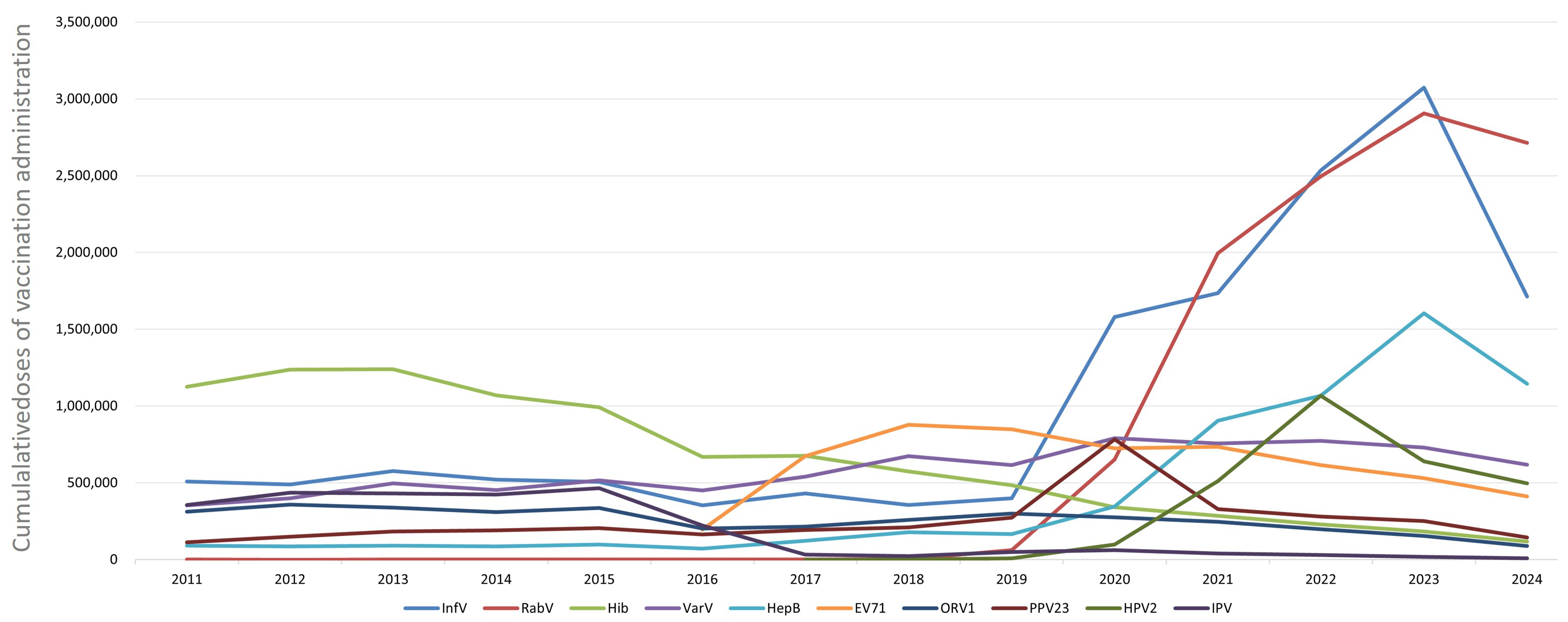

3.2. Administration of Different Non-NIP Vaccines

3.3. Non-NIP Vaccine Administration by Districts

3.4. Administration of Non-NIP Vaccines in Children and Adults

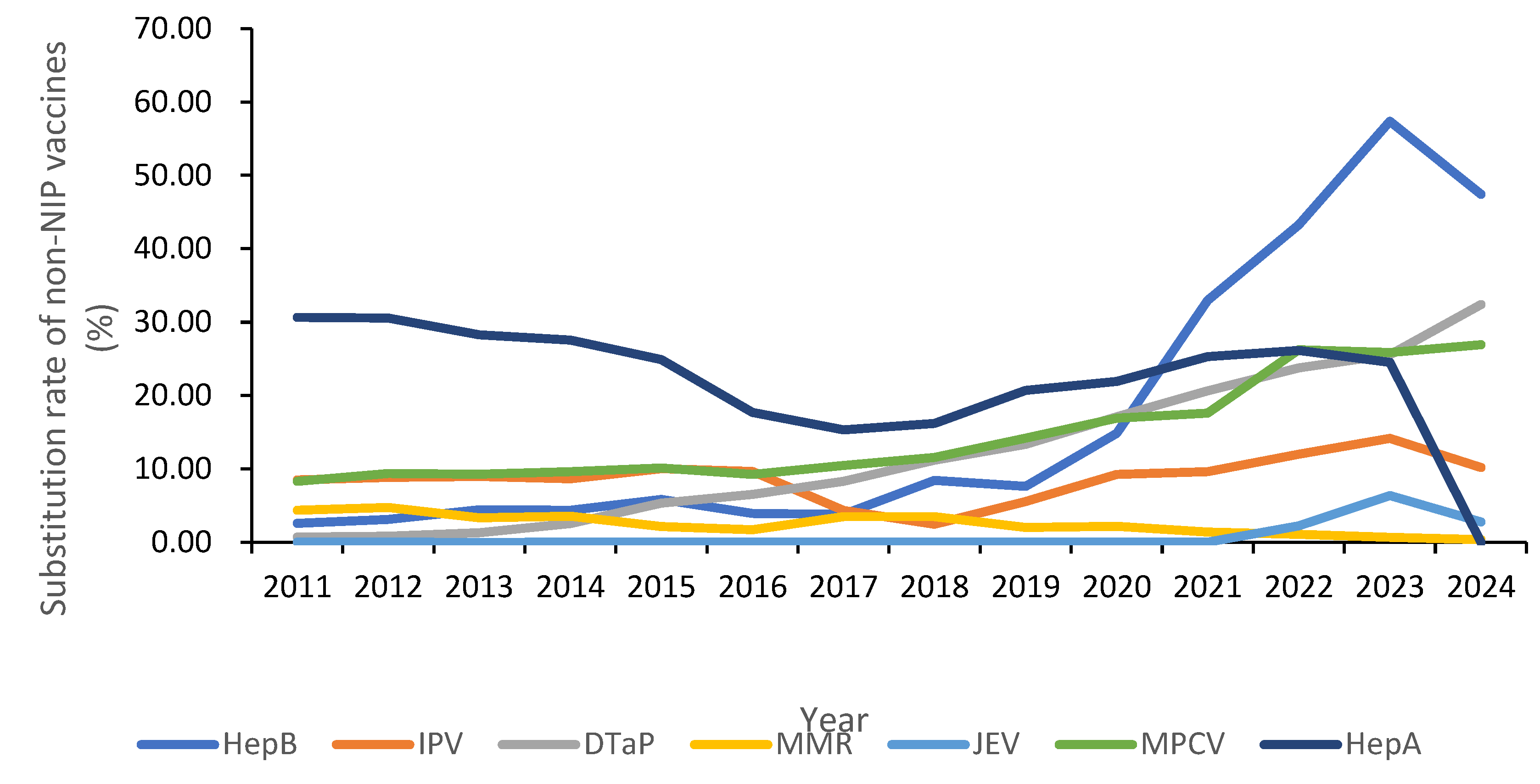

3.5. Administration of Substitutive Non-NIP Vaccines

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, S.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Quddus, S.; Manning, S.H.; Brandt, H.M. Analysis of factors driving HPV vaccination coverage and associated cost savings in the united States. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinardi, J.R.; Thakkar, K.B.; Welch, V.L.; Jagun, O.; Kyaw, M.H. The need for novel influenza vaccines in low- and middle-income countries: A narrative review. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 29, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bußmann, A.; Speckemeier, C.; Schlesiger, P.; Wasem, J.; Bekeredjian-Ding, I.; Ultsch, B. Demand planning for vaccinations using the example of seasonal influenza vaccination—country comparison and implications for Germany. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić-Rajčević, S.; Cvjetković, S.; Oot, L.; Tasevski, D.; Meghani, A.; Wallace, H.; Cotelnic, T.; Popović, D.; Ebeling, E.; Cullen Balogun, T.; et al. Using Behavior Integration to Identify Barriers and Motivators for COVID-19 Vaccination and Build a Vaccine Demand and Confidence Strategy in Southeastern Europe. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranee, S.; Oyindamola Bidemi, Y.; Devon, D.; Kayla, C.; Agnes, M.-K.; Cynthia, L.K. Coverage with Selected Vaccines and Exemption from School Vaccine Requirements Among Children in Kindergarten—United, States, 2022–2023 School Year. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, J.C.D.; França, A.P.; Guibu, I.A.; Barata, R.B.; Silva, A.I.D.; Ramos, A.N., Jr.; Oliveira, A.D.N.M.; Boing, A.F.; Domingues, C.M.A.S.; Oliveira, C.S.D.; et al. Reliability of information recorded on the National Immunization Program Information System. Epidemiol. E Serv. Saude Rev. Sist. Unico Saude Bras. 2024, 33, e20231309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Dong, S.; Gong, J.; Xie, J.; Yan, H. Human papillomavirus vaccination willingness and influencing factors among women in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. Rep. 2025, 58, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lai, X.; Abbas, K.; Pouwels, K.B.; Zhang, H.; Jit, M.; Fang, H. Health impact and economic evaluation of the Expanded Program on Immunization in China from 1974 to 2024: A modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Wang, Q.; Jia, M.; Leng, Z.; Xie, S.; Feng, L.; Yang, W. Driving more WHO-recommended vaccines in the National Immunization Program: Issues and challenges in China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2194190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawelczyk, I.W.; Gołębiewska, A.; Ronkiewicz, P.; Kiedrowska, M.; Błaszczyk, K.; Kuch, A.; Skoczyńska, A. Changes in the Streptococcus pneumoniae population responsible for invasive disease of young children after the implementation of conjugated vaccines in the National Immunization Program in Poland. Vaccine 2025, 64, 127759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, A.E.; Tristán Urrutia, A.G.; Vargas-Zambrano, J.C.; López Castillo, H. Pertussis vaccine effectiveness following country-wide implementation of a hexavalent acellular pertussis immunization schedule in infants and children in Panama. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2389577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, T.T.; Li, Y.J.; Tang, W.J.; Hu, W.J. Analysis of non-national immunization program vaccines inoculated in Shaanxi Province from 2019 to 2023. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi Chin. J. Prev. Med. 2025, 59, 697–701. [Google Scholar]

- Seong-Heon, W.; Jaehun, J.; Joo, W.K. Effective Vaccination and Education Strategies for Emerging Infectious Diseases Such as COVID-19. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2023, 38, e371. [Google Scholar]

- Conceição Silva, F.; De Luca, P.M.; Lima-Junior, J.D.C. Vaccine Development against Infectious Diseases: State of the Art, New, Insights and Future Directions. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, A.; Ta, A.; Vinand, E.; Purdel, V.; Zdrafcovici, A.M.; Ilic, A.; Perdrizet, J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of implementing 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine into the Romanian pediatric national immunization program. J. Med. Econ. 2025, 28, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, D.; Cao, Y.; Lai, F.; Wang, Y.; Long, Q.; Zhang, Z.; An, C.; Xu, X. Immunization, coverage, knowledge, satisfaction, and associated factors of non-National Immunization Program vaccines among migrant and left-behind families in China: Evidence from Zhejiang and Henan provinces. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.; Florencia Lución, M.; Becker Feijo, R.; Luevanos, A.; Gutierrez Tobar, I.F.; Estripeaut, D.; Schilling, A.; Webster, J.; Eugenia Perez, M.; Hirata, L.; et al. Characterizing adolescent vaccination in publicly funded national immunization programs in Latin America and the Caribbean: A review of the literature. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2528403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, M.S.A.; Sutan, R.; Harrun, N.H.; Daud, F.; Merican, N.N.; Abidin, S.I.Z.; Kiau, H.B.; Radzi, A.M.; Thiagarajan, N.; Ishak, N.; et al. Challenges in Integrating Influenza Vaccination Among Older People in National Immunisation Program: A Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Study on, Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices, and Acceptance of a Free Annual Program. Vaccines 2025, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumengen, A.A.; Cakir, G.N.; Tekkas-Kerman, K.; Sahin, R.S.; Subasi, D.O.; Ayaz, V. Pediatric vaccine information on YouTube: A nursing-led content analysis of quality and vaccine hesitancy. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2025, 86, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Yan, X.; Ren, S.; Wang, L. Impact of a Free Influenza Vaccination Policy on Older Adults in, Zhejiang.; China: Cross-Sectional Survey of Vaccination Willingness and Determinants. JMIR Hum. Factors 2025, 12, e73940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, K.; Jia, C.; Zhang, W.; Tan, J.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; et al. The Safety and Immunogenicity of a Quadrivalent Influenza Subunit Vaccine in Healthy Children Aged 6–35 Months: A, Randomized, Blinded and Positive-Controlled Phase III Clinical Trial. Vaccines 2025, 13, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostinov, M.P.; Latysheva, E.A.; Kostinova, A.M.; Akhmatova, N.K.; Latysheva, T.V.; Vlasenko, A.E.; Dagil, Y.A.; Khromova, E.A.; Polichshuk, V.B. Immunogenicity and Safety of the Quadrivalent Adjuvant Subunit Influenza Vaccine in Seropositive and Seronegative Healthy People and Patients with Common Variable Immunodeficiency. Vaccines 2020, 8, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparini, C.; Acunzo, M.; Biuso, A.; Roncaglia, S.; Migliavacca, F.; Borriello, C.R.; Bertolini, C.; Allen, M.R.; Orenti, A.; Boracchi, P.; et al. Nasal spray live attenuated influenza vaccine: The first experience in Italy in children and adolescents during the 2020–21 season. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, Z.; Lou, Q.; Li, T.; Huang, Z.; Yin, W.; Lou, C.; Xiang, Y. Development Strategies for Influenza Vaccines Utilizing Phage RNA Polymerase and Capping Enzyme NP868R. Chem. Bio Eng. 2025, 2, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, E.A.; Lugelo, A.; Czupryna, A.; Anderson, D.; Lankester, F.; Sikana, L.; Dushoff, J.; Hampson, K. Improved effectiveness of vaccination campaigns against rabies by reducing spatial heterogeneity in coverage. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23, e3002872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard for Rabies Exposure Prophylaxis (2023 Edition). Chin. J. Viral Dis. 2024, 14, 22–24.

- Albers, A.N.; Fox, E.R.; Michels, S.Y.; Daley, M.F.; Glanz, J.M.; Newcomer, S.R. Late initiation of pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccinations. Vaccine 2025, 62, 127611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barret, A.S.; François, C.; Deghmane, A.E.; Lefrançois, R.; Mercuriali, L.; Thabuis, A.; Marie, C.; Carraz-Billat, E.; Zanetti, L.; du Châtelet, I.P.; et al. Increase in invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in young children despite high vaccination, coverage, France, 2018–2024. Vaccine 2025, 62, 127499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amimo, F. Rejoinder to comments on “Acceptance and willingness to pay for DTaP-HBV-IPV-Hib hexavalent vaccine among parents: A cross-sectional survey in China”. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2375668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.J.; Cha, H.R.; Kwon, D.; Kang, A.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.E.; Chung, H.W.; Park, S.; Shim, D.H.; et al. Development and Evaluation of Five-in-One Vaccine Microneedle Array Patch for, Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis, Hepatitis, B, Haemophilus influenzae Type b: Immunological Efficacy and Long-Term Stability. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miazga, W.; Tatara, T.; Gujski, M.; Pinkas, J.; Ostrowski, J.; Religioni, U. Global Guidelines and Trends in HPV Vaccination for Cervical Cancer Prevention. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2025, 31, e947173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumakov, K.; Plotkin, S.A. Inactivated Polio Vaccine Must Be an Essential Part of Polio Eradication. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, ciaf215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, W.; Li, W.; Hu, X.; Li, X.; Fan, Q.; Tang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. Immunogenicity evaluation of primary polio vaccination schedule with inactivated poliovirus vaccines and bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsangaise, M.M.; Burnett, R.J.; Ismail, Z.; Meyer, J.C. Negative vaccine sentiments on South African social media platforms before the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed methods study. Front. Health Serv. 2025, 5, 1578992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruoyan, S.; Henna, B. Negative sentiments toward novel coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccines. Vaccine 2022, 40, 6895–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, B.; He, Q.; Ma, J.; Zhang, G. A preliminary analysis of global neonatal disorders burden attributable to PM2. 5 from 1990 to 2019. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 870, 161608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosson, J.F. Medicare Coverage of Vaccines-A Work in Progress. JAMA Intern. Med. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Chen, J.; Mei, Q.; Sun, Y.; Yang, T. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the free vaccination policy on seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among older adults in, Ningbo, Eastern China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2370999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, J. Influencing factors of influenza vaccination willingness among the elderly in Wuxi city: A study based on the Behavioral and Social Drivers (BeSD) framework and structural equation modeling. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2025, 21, 2559508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takata, T.; Enomoto, T.; Matsuo, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Yagi, A.; Kimura, T. Internet Survey: Factors Affecting Human Papillomavirus Vaccination in Japan After Adverse Media Reports. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 114S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Kapre, K.; Andi-Lolo, I.; Kapre, S. Multi-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for global health: From problem to platform to production. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2117949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seinfeld, J.; Sobrevilla, A.; Rosales, M.L.; Ibañez, M.; Munayco, C.; Ruiz, D. Introduction of a hexavalent vaccine containing acellular pertussis into the national immunization program for infants in Peru: A cost-consequence analysis of vaccination coverage. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Number of Vaccine Types | Population (10,000 Persons) | Non-NIP Vaccine Doses | Proportion of Non-NIP Vaccines (%) | Per Capita Utilization of Non-NIP Vaccines (Doses/10,000 Population) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 23 | 5760 | 3,784,730 | 25.52 | 657.07 |

| 2012 | 25 | 5781 | 4,141,160 | 24.38 | 716.34 |

| 2013 | 25 | 5798 | 4,314,150 | 25.11 | 744.08 |

| 2014 | 24 | 5816 | 4,026,918 | 24.31 | 692.39 |

| 2015 | 24 | 5850 | 4,173,382 | 24.92 | 713.40 |

| 2016 | 27 | 5885 | 3,125,483 | 20.91 | 531.09 |

| 2017 | 28 | 5904 | 4,029,452 | 23.96 | 682.50 |

| 2018 | 30 | 5917 | 4,387,819 | 26.63 | 741.56 |

| 2019 | 30 | 5927 | 4,774,901 | 29.88 | 805.62 |

| 2020 | 28 | 5775 | 7,612,584 | 43.41 | 1318.20 |

| 2021 | 28 | 5830 | 9,934,268 | 53.63 | 1703.99 |

| 2022 | 27 | 5844 | 12,494,007 | 62.18 | 2137.92 |

| 2023 | 27 | 5838 | 13,971,544 | 65.95 | 2393.21 |

| 2024 | 28 | 5834 | 10,238,861 | 64.90 | 1755.03 |

| Average | 35 | 5840 | 6,500,661 | 37.98 | 1113.14 |

| District | Cumulative Doses (2011–2024) | Doses in 2011 | Doses in 2024 | Increase (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wuhan City | 18,493,669 | 500,762 | 2,907,308 | 480.58 |

| Huangshi City | 3,276,900 | 187,534 | 346,204 | 84.61 |

| Shiyan City | 5,231,190 | 254,528 | 621,176 | 144.05 |

| Yichang City | 4,477,825 | 198,243 | 649,621 | 227.69 |

| Xiangyang City | 8,790,521 | 449,574 | 979,797 | 117.94 |

| Ezhou City | 1,170,955 | 59,408 | 154,802 | 160.57 |

| Jingmen City | 3,234,638 | 174,668 | 366,531 | 109.84 |

| Xiaogan City | 5,489,735 | 291,669 | 636,960 | 118.38 |

| Jingzhou City | 7,188,469 | 410,665 | 777,796 | 89.40 |

| Huanggang City | 8,274,753 | 432,590 | 935,984 | 116.37 |

| Xianning City | 3,661,528 | 206,442 | 418,850 | 102.89 |

| Suizhou City | 2,359,823 | 114,138 | 303,913 | 166.27 |

| Enshi Autonomous Prefecture | 4,355,147 | 220,854 | 538,740 | 143.93 |

| Xiantao | 1,821,521 | 114,883 | 268,354 | 133.59 |

| Qianjiang City | 1,460,333 | 79,327 | 157,298 | 98.29 |

| Tianmen Autonomous Prefecture | 1,341,270 | 85,249 | 158,869 | 86.36 |

| Shennongjia Forest District | 142,121 | 4196 | 16,658 | 297.00 |

| Total | 80,770,398 | 3,784,730 | 10,238,861 | 170.53 |

| Types of Vaccines | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccines only for children | ||||||||||||||

| Subtotal of vaccine doses (only for children) | 2,495,119 | 2,893,522 | 2,950,745 | 2,764,276 | 2,954,322 | 2,266,925 | 3,050,409 | 3,416,424 | 3,621,217 | 3,747,499 | 3,740,072 | 3,817,855 | 3,663,276 | 2,994,387 |

| Subtotal of vaccine types (only for children) | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 16 |

| Vaccines only for adults | ||||||||||||||

| Subtotal of vaccine doses (only for adults) | 7370 | 5366 | 11,104 | 9077 | 9819 | 3459 | 4220 | 219 | 21 | 1598 | 11,894 | 35,474 | 51,440 | 36,693 |

| Subtotal of vaccine types (only for adults) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Vaccines for both children and adults | ||||||||||||||

| Subtotal of vaccine doses (for both adults and children) | 904,162 | 956,514 | 1,102,166 | 1,036,501 | 1,034,821 | 731,389 | 864,919 | 889,349 | 1,100,217 | 3,813,551 | 6,171,569 | 8,640,642 | 10,250,423 | 7,207,726 |

| Subtotal of vaccine types (for both adults and children) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Total of vaccine doses | 3,784,730 | 4,141,160 | 4,314,150 | 4,026,918 | 4,173,382 | 3,125,483 | 4,029,452 | 4,387,819 | 4,774,901 | 7,612,584 | 9,934,268 | 12,494,007 | 13,971,544 | 10,238,806 |

| Total of vaccine types | 24 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 28 | 27 | 30 | 31 | 28 | 28 | 27 | 27 | 28 |

| Year | Doses of Substitutive Non-EPI Vaccines | Doses of EPI Vaccines Replaced | Substitution Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 651,004 | 11,046,036 | 5.57% |

| 2012 | 794,998 | 12,844,473 | 5.83% |

| 2013 | 823,368 | 12,864,922 | 6.02% |

| 2014 | 844,782 | 12,535,131 | 6.31% |

| 2015 | 946,738 | 12,574,205 | 7.00% |

| 2016 | 768,901 | 11,819,310 | 6.11% |

| 2017 | 780,419 | 12,786,676 | 5.75% |

| 2018 | 884,305 | 12,089,572 | 6.82% |

| 2019 | 1,007,996 | 11,203,367 | 8.25% |

| 2020 | 1,237,888 | 9,922,820 | 11.09% |

| 2021 | 1,513,621 | 8,590,187 | 14.98% |

| 2022 | 1,817,594 | 7,600,859 | 19.30% |

| 2023 | 2,371,146 | 7,213,081 | 24.74% |

| 2024 | 2,175,995 | 5,587,471 | 28.03% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, D. Changed Trends in Utilization and Substitution Pattern of Non-National Immunization Program Vaccines in Central China, 2011–2024. Vaccines 2026, 14, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010016

Wang L, Li H, Zhang L, Li D. Changed Trends in Utilization and Substitution Pattern of Non-National Immunization Program Vaccines in Central China, 2011–2024. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lei, Hao Li, Ling Zhang, and Dan Li. 2026. "Changed Trends in Utilization and Substitution Pattern of Non-National Immunization Program Vaccines in Central China, 2011–2024" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010016

APA StyleWang, L., Li, H., Zhang, L., & Li, D. (2026). Changed Trends in Utilization and Substitution Pattern of Non-National Immunization Program Vaccines in Central China, 2011–2024. Vaccines, 14(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010016