Limited Predictive Utility of Baseline Peripheral Blood Bulk Transcriptomics for Influenza Vaccine Responsiveness in Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing

2.3. Statistical Analysis

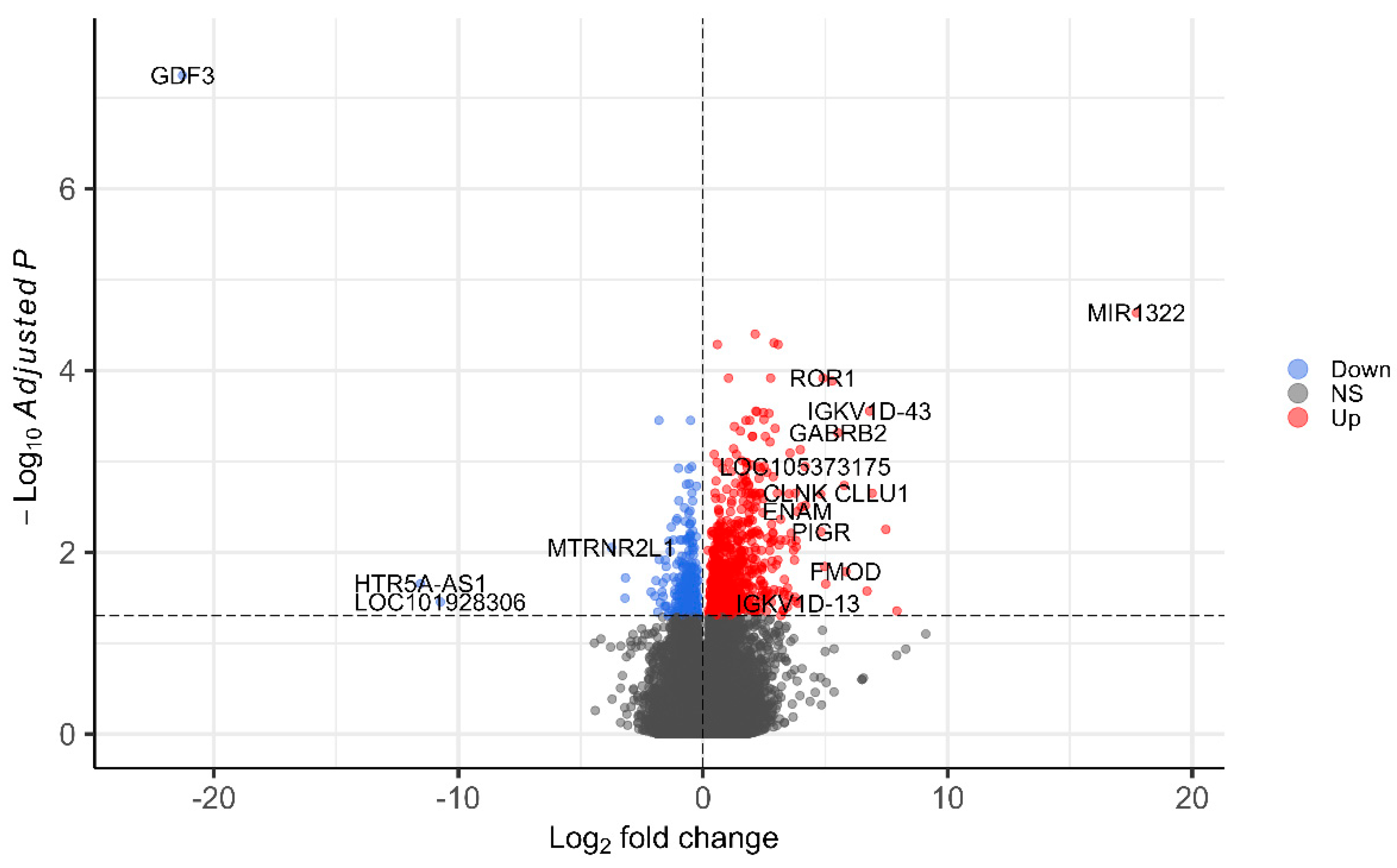

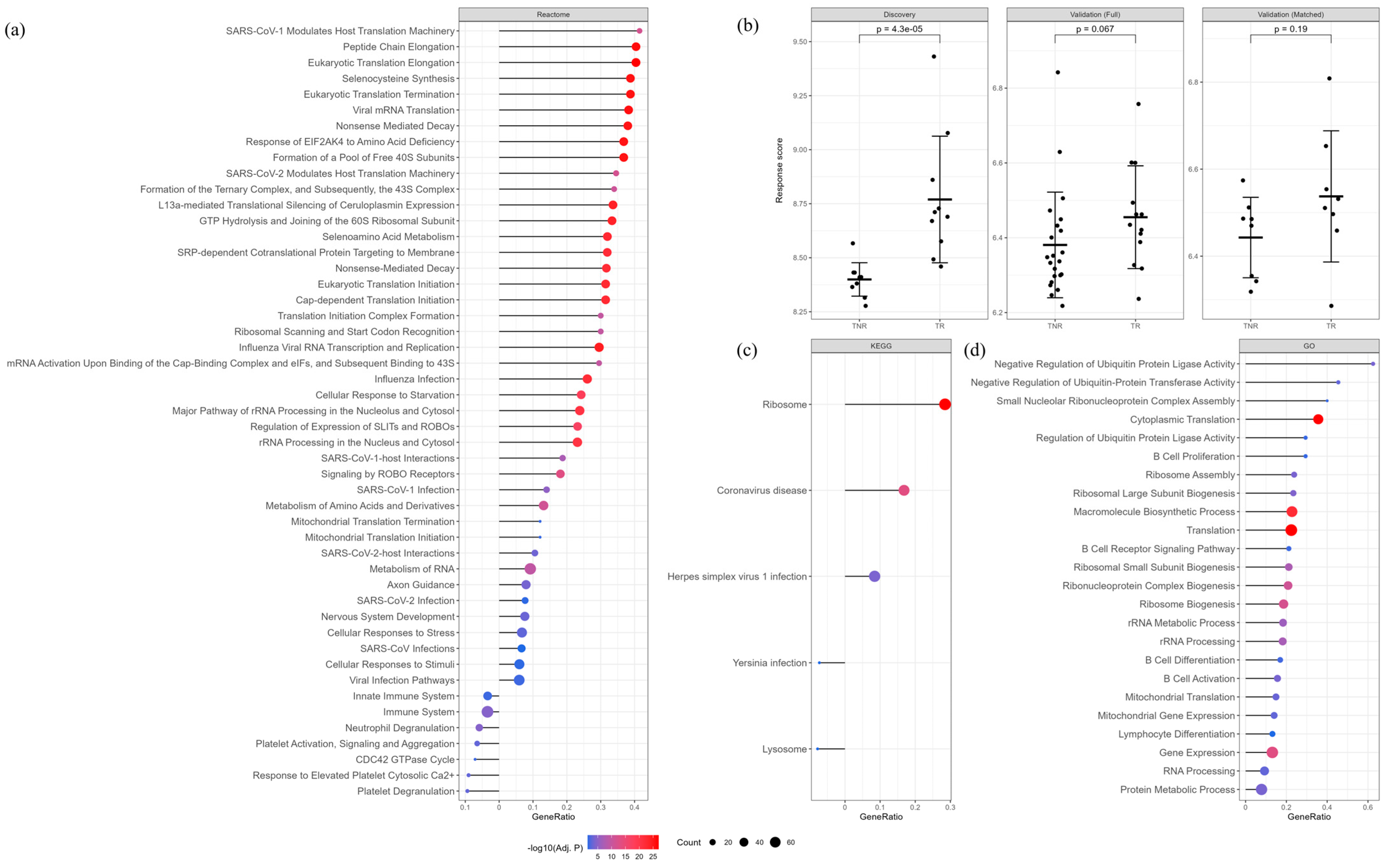

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| DEG | Differentially Expressed Gene |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GMT | Geometric Mean Titer |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HAI | Hemagglutination Inhibition Assay |

| HIPC | Human Immunology Project Consortium |

| NPV | Negative Predictive Value |

| PPV | Positive Predictive Value |

| TNR | Triple Non-Responder |

| TR | Triple Responder |

| Treg | Regulatory T cells |

References

- Feng, J.-N.; Zhao, H.-Y.; Zhan, S.-Y. Global burden of influenza lower respiratory tract infections in older people from 1990 to 2019. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 35, 2739–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, M.K.; Pott, H.; Staadegaard, L.; Paget, J.; Chaves, S.S.; Ortiz, J.R.; McCauley, J.; Bresee, J.; Nunes, M.C.; Baumeister, E.; et al. Age Differences in Comorbidities, Presenting Symptoms, and Outcomes of Influenza Illness Requiring Hospitalization: A Worldwide Perspective From the Global Influenza Hospital Surveillance Network. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10, ofad244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, A.E.; McElhaney, J.E.; Chaves, S.S.; Nealon, J.; Nunes, M.C.; Samson, S.I.; Seet, B.T.; Weinke, T.; Yu, H. The disease burden of influenza beyond respiratory illness. Vaccine 2021, 39, A6–A14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smetana, J.; Chlibek, R.; Shaw, J.; Splino, M.; Prymula, R. Influenza vaccination in the elderly. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.A.; Klassen, A.C.; Ahmed, S.; Agree, E.M.; Louis, T.A.; Naumova, E.N. Trends for influenza and pneumonia hospitalization in the older population: Age, period, and cohort effects. Epidemiol. Infect. 2010, 138, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawelec, G. Age and immunity: What is “immunosenescence”? Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 105, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liang, Q.; Ren, Y.; Guo, C.; Ge, X.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Q.; Luo, P.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X. Immunosenescence: Molecular mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudsmit, J.; van den Biggelaar, A.H.J.; Koudstaal, W.; Hofman, A.; Koff, W.C.; Schenkelberg, T.; Alter, G.; Mina, M.J.; Wu, J.W. Immune age and biological age as determinants of vaccine responsiveness among elderly populations: The Human Immunomics Initiative research program. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joosten, S.A. Individual- and population-associated heterogeneity in vaccine-induced immune responses. The impact of inflammatory status and diabetic comorbidity. Semin. Immunol. 2025, 78, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.-H.; Mohanty, S.; Kang, H.A.; Kong, L.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Joshi, S.R.; Ueda, I.; Devine, L.; Raddassi, K.; Pierce, K.; et al. Metabolomic and transcriptomic signatures of influenza vaccine response in healthy young and older adults. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourati, S.; Tomalin, L.E.; Mulè, M.P.; Chawla, D.G.; Gerritsen, B.; Rychkov, D.; Henrich, E.; Miller, H.E.R.; Hagan, T.; Diray-Arce, J.; et al. Pan-vaccine analysis reveals innate immune endotypes predictive of antibody responses to vaccination. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 1777–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riese, P.; Trittel, S.; Akmatov, M.K.; May, M.; Prokein, J.; Illig, T.; Schindler, C.; Sawitzki, B.; Elfaki, Y.; Floess, S.; et al. Distinct immunological and molecular signatures underpinning influenza vaccine responsiveness in the elderly. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HIPC-CHI Signatures Project Team; HIPC-I Consortium; Avey, S.; Cheung, F.; Fermin, D.; Frelinger, J.; Gaujoux, R.; Gottardo, R.; Khatri, P.; Kleinstein, S.H.; et al. Multicohort analysis reveals baseline transcriptional predictors of influenza vaccination responses. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, eaal4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Pickering, H.; Rubbi, L.; Ross, T.M.; Reed, E.F.; Pellegrini, M. Longitudinal analysis of influenza vaccination implicates regulation of RIG-I signaling by DNA methylation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forst, C.V.; Chung, M.; Hockman, M.; Lashua, L.; Adney, E.; Hickey, A.; Carlock, M.; Ross, T.; Ghedin, E.; Gresham, D. Vaccination History, Body Mass Index, Age, and Baseline Gene Expression Predict Influenza Vaccination Outcomes. Viruses 2022, 14, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, I.G.; Subbarao, K. Implications of the apparent extinction of B/Yamagata-lineage human influenza viruses. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakar, J.; Mohanty, S.; West, A.P.; Joshi, S.R.; Ueda, I.; Wilson, J.; Meng, H.; Blevins, T.P.; Tsang, S.; Trentalange, M.; et al. Aging-dependent alterations in gene expression and a mitochondrial signature of responsiveness to human influenza vaccination. Aging 2015, 7, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknam, B.A.; Zubizarreta, J.R. Using Cardinality Matching to Design Balanced and Representative Samples for Observational Studies. JAMA 2022, 327, 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, P.C. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2011, 46, 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres-Terre, M.; McGuire, H.M.; Pouliot, Y.; Bongen, E.; Sweeney, T.E.; Tato, C.M.; Khatri, P. Integrated, Multi-cohort Analysis Identifies Conserved Transcriptional Signatures across Multiple Respiratory Viruses. Immunity 2015, 43, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Yang, S.; Tu, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, R.; Huang, P. Leveraging baseline transcriptional features and information from single-cell data to power the prediction of influenza vaccine response. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avey, S.; Mohanty, S.; Chawla, D.G.; Meng, H.; Bandaranayake, T.; Ueda, I.; Zapata, H.J.; Park, K.; Blevins, T.P.; Tsang, S.; et al. Seasonal Variability and Shared Molecular Signatures of Inactivated Influenza Vaccination in Young and Older Adults. J. Immunol. 2020, 204, 1661–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farber, D.L. Tissues, not blood, are where immune cells function. Nature 2021, 593, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Lin, F.; Jiang, Z.; Tan, X.; Lin, X.; Liang, Z.; Xiao, C.; Xia, Y.; Guan, W.; Yang, Z.; et al. The impact of pre-existing influenza antibodies and inflammatory status on the influenza vaccine responses in older adults. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2023, 17, e13172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, E.A.; Grill, D.E.; Zimmermann, M.T.; Simon, W.L.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Kennedy, R.B.; Poland, G.A. Transcriptomic signatures of cellular and humoral immune responses in older adults after seasonal influenza vaccination identified by data-driven clustering. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakaya, H.I.; Hagan, T.; Duraisingham, S.S.; Lee, E.K.; Kwissa, M.; Rouphael, N.; Frasca, D.; Gersten, M.; Mehta, A.K.; Gaujoux, R.; et al. Systems Analysis of Immunity to Influenza Vaccination across Multiple Years and in Diverse Populations Reveals Shared Molecular Signatures. Immunity 2015, 43, 1186–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Tamayo, P.; Nakaya, H.; Pulendran, B.; Mesirov, J.P.; Haining, W.N. Gene signatures related to B-cell proliferation predict influenza vaccine-induced antibody response. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 44, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, D.; Jojic, V.; Kidd, B.; Shen-Orr, S.; Price, J.; Jarrell, J.; Tse, T.; Huang, H.; Lund, P.; Maecker, H.T.; et al. Apoptosis and other immune biomarkers predict influenza vaccine responsiveness. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2013, 9, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Discovery | Validation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Population | Matched Population | |||||

| TR (N = 10) | TNR (N = 10) | TR (N = 13) | TNR (N = 22) | TR (N = 8) | TNR (N = 8) | |

| Age (years) | 70.6 {65.0–77.0} | 73.1 {67.0–80.0} | 71.7 {65.0–80.0} | 71.7 {65.0–80.0} | 71.3 {65.0–80.0} | 71.5 {65.0–80.0} |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 7 (70.0) | 8 (80.0) | 2 (15.4) | 14 (63.6) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (12.5) |

| Female | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) | 11 (84.6) | 8 (36.4) | 7 (87.5) | 7 (87.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | - | - | 29.0 [5.7] | 26.8 [5.7] | 27.4 [3.9] | 26.8 [4.5] |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | - | - | 11 (84.6) | 22 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| Other | - | - | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Vaccine dose | ||||||

| Standard | - | - | 5 (38.5) | 5 (22.7) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| High dose | - | - | 8 (61.5) | 17 (77.3) | 6 (75.0) | 6 (75.0) |

| Baseline GMT | 6.30 [6.43] | 45.2 [36.6] | 8.0 [1.6] | 10.0 [9.0] | 7.9 [2.15] | 10.0 [7.4] |

| Dataset | Population | Model | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery | Full population | ~Response score | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.95 |

| ~Baseline GMT | 0.89 | 1.00 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.85 | ||

| ~Baseline GMT + Age + Sex | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.90 | ||

| Validation | Full population | ~Response score | 0.69 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.82 | 0.69 |

| ~Baseline GMT | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.83 | ||

| ~Baseline GMT + Covariates | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.93 | 0.74 | ||

| ~Response score + Baseline GMT + Covariates | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 0.93 | 0.74 | ||

| Matched population | ~Response score | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | |

| ~Baseline GMT | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 | ||

| ~Response score + Baseline GMT | 0.80 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Boissiere-O’Neill, T.; Srihari, S.; Macia, L. Limited Predictive Utility of Baseline Peripheral Blood Bulk Transcriptomics for Influenza Vaccine Responsiveness in Older Adults. Vaccines 2026, 14, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010012

Boissiere-O’Neill T, Srihari S, Macia L. Limited Predictive Utility of Baseline Peripheral Blood Bulk Transcriptomics for Influenza Vaccine Responsiveness in Older Adults. Vaccines. 2026; 14(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoissiere-O’Neill, Thomas, Sriganesh Srihari, and Laurence Macia. 2026. "Limited Predictive Utility of Baseline Peripheral Blood Bulk Transcriptomics for Influenza Vaccine Responsiveness in Older Adults" Vaccines 14, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010012

APA StyleBoissiere-O’Neill, T., Srihari, S., & Macia, L. (2026). Limited Predictive Utility of Baseline Peripheral Blood Bulk Transcriptomics for Influenza Vaccine Responsiveness in Older Adults. Vaccines, 14(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines14010012