A Narrative Review on How Timing Matters: Circadian and Sleep Influences on Influenza Vaccine Induced Immunity

Abstract

1. Introduction

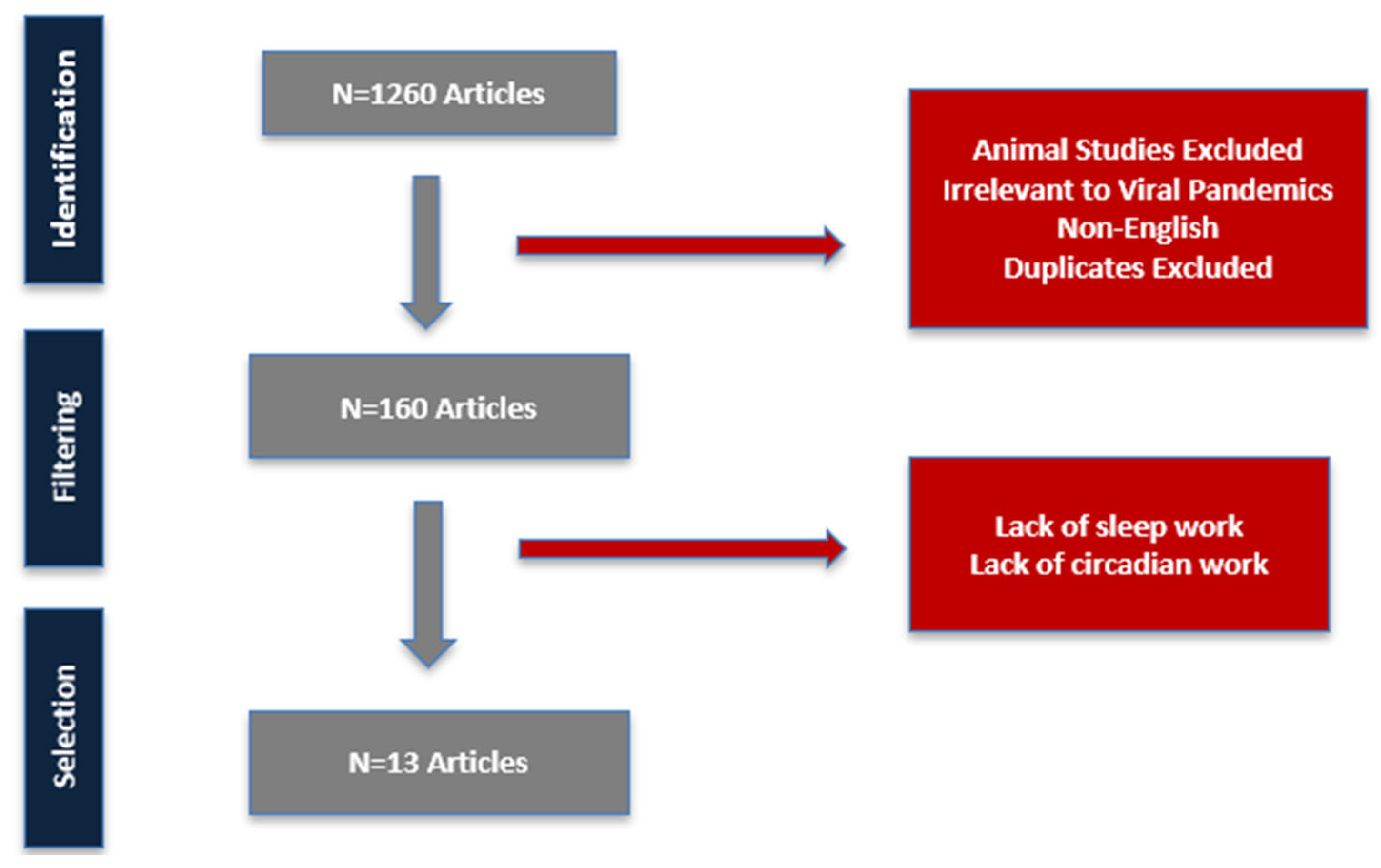

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Time-of-Day Vaccination on Immunogenicity

3.2. Sleep Findings

3.3. Light Exposure and Circadian Stability

3.4. Circadian Misalignment and Shift Work

3.5. Clinical Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanistic Basis of Morning Vaccine-Induced Immune Response

4.2. Sleep Duration, Quality and Continuity

4.3. Light Exposure

4.4. Impact of Circadian Misalignment and Shift Work

4.5. Circadian Disruption and Vulnerable Populations

4.6. Broad Vaccination Insights

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. Factors That Influence the Immune Response to Vaccination. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00084-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Chen, P.; Qi, C. Circadian rhythm regulation in the immune system. Immunology 2024, 171, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haspel, J.A.; Anafi, R.; Brown, M.K.; Cermakian, N.; Depner, C.; Desplats, P.; Gelman, A.E.; Haack, M.; Jelic, S.; Kim, B.S.; et al. Perfect timing: Circadian rhythms, sleep, and immunity—An NIH workshop summary. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e131487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermakian, N.; Stegeman, S.K.; Tekade, K.; Labrecque, N. Circadian rhythms in adaptive immunity and vaccination. Semin. Immunopathol. 2022, 44, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downton, P.; Early, J.O.; Gibbs, J.E. Circadian rhythms in adaptive immunity. Immunology 2020, 161, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reglero-Real, N.; Rolas, L.; Nourshargh, S. Leukocyte Trafficking: Time to Take Time Seriously. Immunity 2019, 50, 273–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, K.; Rey, A.E.; Cheylus, A.; Ayling, K.; Benedict, C.; Lange, T.; Prather, A.A.; Taylor, D.J.; Irwin, M.R.; Van Cauter, E. A meta-analysis of the associations between insufficient sleep duration and antibody response to vaccination. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 998–1005.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauman, R.; Henig, O.; Rosenberg, E.; Marudi, O.; Dunietz, T.M.; Grandner, M.A.; Spitzer, A.; Zeltser, D.; Mizrahi, M.; Sprecher, E.; et al. Relationship among sleep, work features, and SARS-cov-2 vaccine antibody response in hospital workers. Sleep Med. 2024, 116, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, O.; Tavella, F.; Zeitzer, J.M.; Lok, R. Beyond phase shifting: Targeting circadian amplitude for light interventions in humans. Sleep 2025, 48, zsae247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Oh, C.E. Sleep and vaccine administration time as factors influencing vaccine immunogenicity. KMJ 2022, 37, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, K.; Kusters, J.; Wallinga, J. Chrono-optimizing vaccine administration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1516523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.; Johansen, N.D.; Janstrup, K.H.; Modin, D.; Skaarup, K.G.; Nealon, J.; Samson, S.; Loiacono, M.; Harris, R.; Larsen, C.S.; et al. Time of day for vaccination, outcomes, and relative effectiveness of high-dose vs. standard-dose quadrivalent influenza vaccine: A post hoc analysis of the DANFLU-1 randomized clinical trial. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, G.; Yao, M.; Li, B.; Chen, J.; Fan, Y.; Mo, R.; Lai, F.; Chen, X.; et al. The impact of circadian rhythms on the immune response to influenza vaccination in middle-aged and older adults (IMPROVE): A randomised controlled trial. Immun. Ageing 2022, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.E.; Drayson, M.T.; Taylor, A.E.; Toellner, K.M.; Lord, J.M.; Phillips, A.C. Corrigendum to ‘Morning vaccination enhances antibody response over afternoon vaccination: A cluster-randomised trial’ [Vaccine 34 (2016) 2679–2685]. Vaccine 2016, 34, 4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Münch, M.; Goldbach, R.; Zumstein, N.; Vonmoos, P.; Scartezzini, J.L.; Wirz-Justice, A.; Cajochen, C. Preliminary evidence that daily light exposure enhances the antibody response to influenza vaccination in patients with dementia. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2022, 26, 100515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, A.C.; Gallagher, S.; Carroll, D.; Drayson, M. Preliminary evidence that morning vaccination is associated with an enhanced antibody response in men. Psychophysiology 2008, 45, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurupati, R.K.; Kossenkoff, A.; Kannan, S.; Haut, L.H.; Doyle, S.; Yin, X.; Schmader, K.E.; Liu, Q.; Showe, L.; Ertl, H.C.J. The effect of timing of influenza vaccination and sample collection on antibody titers and responses in the aged. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3700–3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlois, P.H.; Smolensky, M.H.; Glezen, W.P.; Keitel, W.A. Diurnal Variation in Responses to Influenza Vaccine. Chronobiol. Int. 1995, 12, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustini, S.E.; Backhouse, C.; Duggal, N.A.; Toellner, K.M.; Harvey, R.; Drayson, M.T.; Lord, J.M.; Richter, A.G. Time of day of vaccination does not influence antibody responses to pneumococcal and annual influenza vaccination in a cohort of healthy older adults. Vaccine 2025, 49, 126770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.U.; Watson, N.L.; Glickman, G.L.; White, L.; Isidean, S.D.; Porter, C.K.; Hollis-Perry, M.; Walther, S.R.; Maiolatesi, S.; Sedegah, M.; et al. A randomized clinical trial of the impact of melatonin on influenza vaccine: Outcomes from the melatonin and vaccine response immunity and chronobiology study (MAVRICS). Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2024, 20, 2419742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, A.A.; Pressman, S.D.; Miller, G.E.; Cohen, S. Temporal Links Between Self-Reported Sleep and Antibody Responses to the Influenza Vaccine. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 28, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, C.; Brytting, M.; Markström, A.; Broman, J.E.; Schiöth, H.B. Acute sleep deprivation has no lasting effects on the human antibody titer response following a novel influenza A H1N1 virus vaccination. BMC Immunol. 2012, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, H.Q.; Warner, N.D.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Covassin, N.; Poland, G.A.; Somers, V.K.; Kennedy, R.B. Excessive daytime sleepiness is associated with impaired antibody response to influenza vaccination in older male adults. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1229035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.J.; Kelly, K.; Kohut, M.L.; Song, K.S. Is Insomnia a Risk Factor for Decreased Influenza Vaccine Response? Behav. Sleep Med. 2017, 15, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyse, C.A.; Rudderham, L.M.; Nordon, E.A.; Ince, L.M.; Coogan, A.N.; Lopez, L.M. Circadian Variation in the Response to Vaccination: A Systematic Review and Evidence Appraisal. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2024, 39, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, G.; Duek, O.A.; Alapi, H.; Mok, H.; Ganninger, A.; Ostendorf, E.; Gierasch, C.; Chodick, G.; Greenberg, D.; Haspel, J.A. Biological rhythms in COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in an observational cohort study of 1.5 million patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e167339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, N.; Harvey, A.G.; Lockley, S.W.; Dijk, D.J. Circadian rhythms and disorders of the timing of sleep. Lancet 2022, 400, 1061–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Cho, J.W.; Kim, J.H.; Moon, H.J.; Park, H.R.; Cho, Y.W. Sleep and Circadian Rhythm in Relation to COVID-19 and COVID-19 Vaccination-National Sleep Survey of South Korea 2022. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, T.; Dimitrov, S.; Bollinger, T.; Diekelmann, S.; Born, J. Sleep after vaccination boosts immunological memory. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, T.; Perras, B.; Fehm, H.L.; Born, J. Sleep enhances the human antibody response to hepatitis A vaccination. Psychosom. Med. 2003, 65, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.J.; Gadaleta, M.; Quer, G.; Radin, J.M.; Waalen, J.; Ramos, E.; Pandit, J.; Owens, R.L. Objectively measured peri-vaccination sleep does not predict COVID-19 breakthrough infection. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayatdoost, E.; Rahmanian, M.; Sanie, M.S.; Rahmanian, J.; Matin, S.; Kalani, N.; Kenarkoohi, A.; Falahi, S.; Abdoli, A. Sufficient sleep, time of vaccination, and vaccine efficacy: A systematic review of the current evidence and a proposal for COVID-19 vaccination. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2022, 95, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lai, F.; Li, B.; Mei, J.; Zhou, Q.; Long, J.; Liang, R.; Mo, R.; Peng, S.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, H. The impact of vaccination time on the antibody response to an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 (IMPROVE-2): A randomized controlled trial. Adv. Biol. 2023, 7, e2300028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Zeng, Q.; Li, L.; Zhou, Q.; Li, M.; Mei, J.; Yang, N.; Mo, S.; et al. Time of day influences immune response to an inactivated vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Balfe, P.; Eyre, D.W.; Lumley, S.F.; O’Donnell, D.; Warren, F.; Crook, D.W.; Jeffery, K.; Matthews, P.C.; Klerman, E.B.; et al. Time of day of vaccination affects SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in an observational study of healthcare workers. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2022, 37, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loef, B.; Dollé, M.E.T.; Proper, K.I.; van Baarle, D.; Initiative, L.C.R.; van Kerkhof, L.W. Night-shift work is associated with increased susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Chronobiol. Int. 2022, 39, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otasowie, C.O.; Tanner, R.; Ray, D.W.; Austyn, J.M.; Coventry, B.J. Chronovaccination: Harnessing circadian rhythms to optimize immunisation strategies. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 977525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, N.C.M.; van der Werf, Y.D.; Lammers-van der Holst, H.M. The Importance of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms for Vaccination Success and Susceptibility to Viral Infections. Clocks Sleep 2022, 4, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghini, G.M.; Thurnheer, R.; Kahlert, C.R.; Kohler, P.; Grässli, F.; Stocker, R.; Battegay, M.; Vuichard-Gysin, D. Impact of shift work and other work-related factors on anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein serum concentrations in healthcare workers after primary mRNA vaccination—A retrospective cohort study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2024, 154, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwers, T.M.J.; Çobanoğlu, Ü.G.; Geers, D.; Rietdijk, W.J.R.; Gommers, L.; Bogers, S.; Lammers, G.J.; van der Horst, G.T.J.; Chaves, I.; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H.; et al. The effect of sleep and shift work on the primary immune response to messenger RNA-based COVID-19 vaccination. J. Sleep. Res. 2024, 34, e14431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigazzani, F.; Dyar, K.A.; Morant, S.V.; Vetter, C.; Rogers, A.; Flynn, R.W.V.; Rorie, D.A.; Mackenzie, I.S.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Manfredini, R.; et al. Effect of timed dosing of usual antihypertensives according to patient chronotype on cardiovascular outcomes: The Chronotype sub-study cohort of the Treatment in Morning versus Evening (TIME) study. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 72, 102633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiou, N.; Baou, K.; Papandreou, E.; Varsou, G.; Amfilochiou, A.; Kontou, E.; Pataka, A.; Porpodis, K.; Tsiouprou, I.; Kaimakamis, E.; et al. Association of sleep duration and quality with immunological response after vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e13656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opp, M.R. Sleep: Not getting enough diminishes vaccine responses. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R192–R194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, H.; Ostendorf, E.; Ganninger, A.; Adler, A.J.; Hazan, G.; Haspel, J.A. Circadian immunity from bench to bedside: A practical guide. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e175706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, F.S.; Rosa, D.S.; Zimberg, I.Z.; Dos Santos Quaresma, M.V.; Nunes, J.O.; Apostolico, J.S.; Weckx, L.Y.; Souza, A.R.; Narciso, F.V.; Fernandes-Junior, S.A.; et al. Night shift work and immune response to the meningococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy workers: A proof of concept study. Sleep Med. 2020, 75, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ince, L.M.; Barnoud, C.; Lutes, L.K.; Pick, R.; Wang, C.; Sinturel, F.; Chen, C.S.; de Juan, A.; Weber, J.; Holtkamp, S.J.; et al. Influence of circadian clocks on adaptive immunity and vaccination responses. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relan, P.; Motaze, N.V.; Kothari, K.; Askie, L.; Le Polain, O.; Van Kerkhove, M.D.; Diaz, J.; Tirupakuzhi Vijayaraghavan, B.K. Severity and outcomes of Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 compared to Delta variant and severity of Omicron sublineages: A systematic review and metanalysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e012328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Country (Region) | Age Range/Mean Age | Gender Stratification | Study Design | N (Sample Size) | Study Period | Vaccine Type | Other Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen J et al., 2024 [12] | Denmark | 65–79 yrs (mean 71.7 ± 3.9 yrs) | 47.1% female (5 877/12,477) | Post hoc analysis of pragmatic, open-label RCT (QIV-HD vs. QIV-SD) | 12,477 | Vaccinations 1 Oct 2021–20 Nov 2021; FU to 31 May 2022 | High-dose vs. standard-dose quadrivalent influenza | Vaccination times 07:05 AM–08:08 PM (median 11:29 AM); early vs. late groups by median; registry-based comorbidity capture; outcomes via passive registry follow-up |

| Liu Y et al., 2022 [13] | China | 50–75 yrs (mean 62.8 ± 7.2 yrs) | 37.5% male, 62.5% female | Individual RCT; morning (9–11 AM) vs. afternoon (3–5 PM) vaccination with stratified block randomization | 418 | Enrolment 27 Oct 2020–22 Dec 2020; FU at 1 mo and 3 mo post-vax | Trivalent inactivated influenza (Sanofi split virion: H1N1 pdm09, H3N2, B/Victoria) | Baseline blood draw 8–10 AM; subgroup by age and sex; no serious AEs |

| Long JE et al., 2016 [14] | UK (West Midlands) | ≥65 yrs (mean 71.3 ± 5.5 yrs) | 52.2% female overall | Cluster RCT: 24 GP surgeries randomized annually to morning (9–11 AM) vs. afternoon (3–5 PM); baseline and 1 mo blood draws | 298 consented; 276 analyzed | Enrolment 28 Oct 2011–12 Nov 2013; FU Dec 2013 | Trivalent inactivated seasonal influenza (2011/12–2013/14; Pfizer Enzira®, Sanofi, BGP, GSK, Janssen formulations) | No acute infection/immunosuppressants; combined H1N1/H3N2/B analysis |

| Münch M et al., 2022 [15] | Switzerland (Wetzikon, Zurich) | 55–95 yrs (mean 78.3 ± 8.9 yrs) | 67.5% female, 32.5% male | Cross-sectional: 8 wk light monitoring; split into high- vs. low-illuminance groups; vaccination wk 44; 4 wk post-vax titers | 80 | Fall/winter 2012; vaccination wk 44; 4-wk FU | Trivalent inactivated influenza (Fluarix®: H3N2, H1N1, IB; 2012/13 WHO) | Institutionalized dementia; median illuminance 392.7 lux; HAI assay; no serious AEs |

| Phillips AC et al., 2008 [16] | UK (Birmingham) | Study 1: 22.9 ± 3.9 yrs; Study 2: 73.1 ± 5.5 yrs | Study 1: 34 M/41 F; Study 2: 38 M/51 F | (1) RCT: hepatitis A (10–12 PM vs. 4–6 PM); (2) observational: influenza (8–11 AM vs. 1–4 PM); ~1 mo blood draws | 75/89 | Baseline and ~28–31 days post-vax | Trivalent influenza (2003–04: A/New Caledonia; A/Panama; B/Shangdong) | Predominantly White; enzyme immunoassay and HAI; men showed higher AM responses |

| Kurupati RK et al., 2017 [17] | USA (Durham,) | Younger: 30–40 yrs; elderly: ≥65 yrs | Not stratified | 5 yr cohort: AM vs. PM grouping; VNA, IgG/IgM/IgA, B-cell subsets, transcriptomics from matched samples | 59/80 | 2011–2015 seasons; pre-vax, days 7, 14/28 draws | Trivalent inactivated influenza (Fluarix™ trivalent or quadrivalent) | Community adults; higher baseline PM titers in elderly patients drove fold-response patterns |

| Langlois PH et al., 1995 [18] | USA (Princeton,) | Adult volunteers (N/A) | N/A | Field trials: summer 1984 and revaccination 1985 (Princeton); autumn 1985 (Houston); AM vs. PM injections; antibody and local reaction assessment | N/A | Summer 1984; revaccination 1985; autumn 1985 | Trivalent inactivated influenza (A/Philippines; A/Chile; B/USSR) | Diurnal pattern for A/Philippines only; more local reactions PM |

| Faustini SE et al., 2025 [19] | UK (Birmingham) | > 50 yrs (mean 57.0 ± 6.7 yrs) | 65.0% female, 35.0% male | Observational: self-selected AM (8–10 AM) vs. PM (4–6 PM); co-admin of PPV23+quadrivalent influenza; multiplex Luminex, HAI, cytokines, hsCRP, cortisol | 140 | Jun 2018–Feb 2020; seasons 2018–19 and 2019–20; FU to 52 wks | PPV23 (Pneumovax®) & quadrivalent influenza (2018–19 Sanofi); 2019–20 Flucelvax-tetra) | Healthy > 50; excluded recent PPV23 or current-year flu; no diurnal effect; sustained immunity at 1 yr |

| Lee RU et al., 2024 [20] | USA (Bethesda/Silver Spring, MD) | 18–64 yrs (mean 38 ± 12 yrs) | 50.9% female | Open-label RCT: melatonin (5 mg) vs. control for 14 days post-vax; HAI and FluoroSpot at 14–21 days | 108 (53 M; 55 C) | Oct 2022–Jan 2023; FU at 14–21 days post-vax | FluLaval® Quadrivalent 2022/23 (A/Victoria; A/Darwin; B/Austria; B/Phuket) | Melatonin 1 h pre-bed; increases IFN-γ + GzB double-secretor GMFR; no HAI differences |

| Prather A.A. et al., 2021 [21]) | USA (multiple universities) | 18–25 yrs (mean 18.3 ± 0.9 yrs) | 55.4% female (46/83) | Prospective: 13 d sleep diaries; vaccination on day 3; HAI at baseline, 1 mo, 4 mo | 83 | Sep–Nov 2000 and 2001; 13 d monitoring; FU at 1 mo and 4 mo | Fluzone® (A/New Caledonia; A/Panama; B/Yamanashi or B/Victoria) | College freshmen; shorter sleep pre-vax predicted lower titers |

| Benedict C et al., 2012 [22] | Sweden (Uppsala and Solna) | ~ 20.5 yrs | 54.2% female (13/24) | Randomized: 24 h sleep deprivation vs. normal sleep post-H1N1 (Pandemrix™); HAI at days 5, 10, 17, 52 | 24 (13 sleep; 11 SD) | Vaccination 27 Nov 2009; FU days 5, 10, 17, 52 (2010) | Pandemrix™ (H1N1) | Healthy students; reduced day 5 antibody in SD males only; no lasting difference |

| Quach H.Q. et al., 2023 [23] | USA (Rochester, MN) | ≥ 65 yrs (median 71.3 yrs) | 61.4% female (129/210) | Prospective cohort: HD Flu vs. MF59Flu; STOP/ESS/PSQI; HAI at day 0 and 28; questionnaires ~1 yr post-vax | 210 | Aug–Dec 2018; blood day 0 and 28; ~1 yr questionnaires | HD or adjuvanted trivalent influenza (A/H1N1; A/H3N2; B) | Male excessive daytime sleepiness lowers H3N2 titers at D0 and D28; no OSA or PSQI effects |

| Taylor D.J. et al., 2020 [24] | USA (Denton) | 18–29 yrs (mean 20.24 ± 2.60 yrs) | 60% female (80/133) | Repeated-measures cohort: chronic insomnia (n = 65) vs. no insomnia (n = 68); structured clinical interview; blood at baseline (12–2 PM) and 4 wk post-vax | 133 (65 Ins; 68 NoIns) | Recruitment 2011 and 2012 seasons; blood draws Sep–early Nov | Trivalent inactivated influenza (2011/12: A/California/7/2009; A/Perth/16/2009; B/Brisbane/60/2008; 2012/13: A/California/7/2009; A/Victoria/361/2011; B/Wisconsin/1/2010) | Healthy young adults; rigorous insomnia diagnosis (SCID-I/II, ISI, PSQI, ESS, MEQ); blood drawn 12–2 PM to control diurnal; insomnia group had lower baseline and post-vax H3N2 and B titers; no Group/Time interaction |

| Included Study | Primary Outcome | Times of Vaccination and Type of Vaccine | Findings | Sleep and Circadian Parameters | Contradictory Findings, Null Results, and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liu Y et al., 2022, China [13] | Antibody titer responses to influenza vaccination | 9–11 AM vs. 3–5 PM; trivalent inactivated influenza | In 65–75 yr subgroup, morning increased A/H1N1 (49.5 vs. 32.9; p = 0.050) and increased A/H3N2 (93.5 vs. 73.1; p = 0.021) | None reported | Overall null except subgroup signals; limited generalizability beyond older adults and women |

| Long JE et al., 2016, UK [14] | Change in antibody titers one month post-vaccination | 9–11 AM vs. 3–5 PM; trivalent seasonal influenza | Morning slots enhanced A/H1N1 response (263.6, 95% CI –1.62 to 525.59; p = 0.05) | None assessed | Strain-specific effect; no A/H3N2 change; cluster design and non-blinding may affect inference |

| Phillips AC et al., 2008, UK [16] | Antibody titer response to influenza vaccine | 8–11 AM vs. 1–4 PM; 2003–04 trivalent influenza | Men vaccinated AM had higher A/Panama GMT (F(1,84) = 5.93; p = 0.02); no effect in women | Diurnal rhythm inference only | Effects limited to men; small n; potential for unmeasured confounding |

| Kurupati RK et al., 2017, USA [17] | Antibody titer responses to influenza vaccination | 8 AM–12 PM vs. 12–5 PM; Fluarix™ tri-/quadrivalent | In elderly group, morning increased H1N1 titers vs. PM; but higher baseline PM titers confounded fold-rise calculations (p < 0.05) | Timing of blood draw | Confounded by sample-collection time; limits clear assignment of vaccine-time effect |

| Langlois P.H. et al., 1995, USA [18] | Hemagglutination-inhibition titers (three flu strains) | Morning vs. afternoon IM injections across normal work hours | Princeton 1984: AM > PM for A/Philippines only; no effect for other strains or in revaccination cohorts | Clock-time of injection only | Strain- and year-specific; non-random time assignment; possible site/season confounding |

| Faustini S.E. et al., 2025, UK [19] | Pneumococcal IgG/IgA/IgM and influenza HAI titers over 1 year | AM (08:00–10:00) vs. PM (16:00–18:00); PPV-23 + quadrivalent influenza | Both groups increased pneumococcal and influenza titers; no time-of-day differences in magnitude or durability for any isotype/strain | Questionnaire on sleep duration, activity, diet; cortisol/cytokine profiling | Null contrasts earlier elderly findings; self-selected slots; younger cohort; co-administration may dilute effect; only two time windows tested |

| Included Study | Primary Outcome | Intervention/Exposure and Vaccine | Findings | Sleep and Circadian Parameters | Contradictory Findings, Null Results, and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benedict C et al., 2012, Sweden [22] | HAI titer response to H1N1 vaccination | Sleep 8 h vs. total sleep deprivation; Pandemrix™ | SD males only showed lower day-5 HAI (60% lower; p ≤ 0.05); no lasting differences by day 10, 17, 52 | 24 h sleep deprivation | Small sample size; sex-specific transient effect; no sustained impact |

| Lee R.U. et al., 2024, USA [20] | Humoral (HAI) and cellular (FluoroSpot) responses | 5 mg melatonin nightly × 14 days post-flu shot | No HAI differences; melatonin increased IFN-γ + GzB double-secretor GMFR at 14–21 days | Melatonin taken about57 min before sleep | Small pilot; only cellular endpoints positive; requires replication |

| Prather A.A. et al., 2021, USA [21] | HAI titers at 1 mo and 4 mo post-vaccination | 13 days self-reported sleep diaries; trivalent influenza | Shorter sleep nights 2–3 pre-vax predicted ↓ 1 mo and 4 mo HAI titers; no effect of sleep efficiency or quality | Sleep duration, efficiency, quality via diary | Subjective reporting; small sample; no sleep quality effects |

| Quach H.Q. et al., 2023, USA [23] | HAI titers to A/H3N2 at Day 0 and 28 | HDFlu or MF59Flu; ESS, STOP-BANG, PSQI | Excessive daytime sleepiness in men lowered H3N2 titers at D0 (p = 0.03) and D28 (p = 0.019); no effect in women; no OSA/sleep quality associations | ESS, STOP-BANG, PSQI; daytime sleepiness | Male-specific; observational/recall bias; cannot infer causation |

| Taylor D.J. et al., 2020, USA [24] | HAI titers at baseline and 4 wk post-vax | Chronic insomnia vs. no insomnia; trivalent influenza | Insomnia group ↓ baseline and 4 wk H3N2 (p = 0.008) and B (p = 0.009) titers; no Group andTime interaction | SCID, ISI, PSQI, ESS, MEQ; sleep diaries | Healthy young cohort; subjective measures; no analysis of acute sleep deprivation |

| Included Study | Primary Outcome | Exposure and Vaccine | Findings | Sleep and Circadian Parameters | Contradictory Findings, Null Results, and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Münch M et al., 2022, Switzerland [15] | HAI titers to H1N1, H3N2, IB | High vs. low daily light; Fluarix® seasonal influenza | High-light group increased H3N2 GMT by ratio 9.9 (95% CI 3.2; p = 0.01) vs. low-light; no serious AEs | Higher light increased relative amplitude and inter-daily stability of rest and activity | Preliminary in dementia; small n; needs replication |

| Included Study | Primary Outcome | Times of Vaccination and Type of Vaccine | Findings | Sleep and Circadian Parameters | Contradictory Findings, Null Results, and Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christensen J et al., 2024, Denmark [12] | Incidence of respiratory hospitalizations and allcause mortality | 7:05 AM–8:08 PM; QIV-HD vs. QIV-SD; early vs. late (median 11:29 AM) | Early vaccination leads to fewer respiratory hospitalizations; QIV-HD decreased pneumonia/influenza admissions (IRR 0.30; 95% CI 0.14–0.64) | Explored circadian timing; no sleep outcomes directly measured | Exploratory post hoc; observational nature; no time/vaccine type interaction; needs confirmation |

| Section | Parameter | Impact on Vaccine Outcome | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of Time-of-Day Vaccination | Time of Vaccination | Morning vaccinations yield stronger immune responses, especially in older adults | Morning shots generally produce higher antibody titers—particularly in older subgroups—but effect size and strain specificity vary (e.g., no significant difference for influenza A/H3N2 in some trials). |

| Sleep Findings | Sleep Duration | Shorter sleep duration reduces vaccine-induced antibody responses | Consistent evidence shows that shorter sleep—especially the 1–2 nights before vaccination—significantly impairs antibody production. Acute 24 h deprivation causes transient titer drops that recover by day 10–17. |

| Sleep Quality | Poor sleep quality (fragmented sleep) may compromise vaccine-induced immunity | Findings are mixed: some studies link fragmented sleep to greater post-vaccine infection risk, but not all show significant antibody-titer reductions. | |

| Chronic Insomnia | Chronic insomnia and fragmented sleep may impair vaccine responses | Insomnia cohorts often have lower baseline and post-vax titers for select strains; sleep fragmentation more clearly impacts cellular markers. Melatonin boosts cellular responses but not consistently antibody titers. | |

| Light Exposure and Circadian Stability | Light Exposure | Higher daily light exposure enhances antibody responses via improved circadian stability | Preliminary data in institutionalized dementia patients show high-light groups mount significantly greater H3N2 titers at 4 weeks—likely via strengthened rest-activity rhythms. |

| Circadian Misalignment and Shift Work | Circadian Disruption | Immune response may be blunted in individuals with disrupted rhythms (e.g., shift workers) | Evidence is mixed: some report reduced antibody responses under misalignment, while others find no humoral change but altered cellular markers in night-shift groups. Older adults appear particularly vulnerable to misalignment, compounding immunosenescence. |

| Clinical Outcomes | Clinical Endpoints | Morning vaccination linked to reduced hospitalizations and mortality | Early quadrivalent influenza vaccination was associated with fewer respiratory hospitalizations and lower pneumonia/influenza admissions but findings are exploratory. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Livieratos, A.; Zeitzer, J.M.; Tsiodras, S. A Narrative Review on How Timing Matters: Circadian and Sleep Influences on Influenza Vaccine Induced Immunity. Vaccines 2025, 13, 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080845

Livieratos A, Zeitzer JM, Tsiodras S. A Narrative Review on How Timing Matters: Circadian and Sleep Influences on Influenza Vaccine Induced Immunity. Vaccines. 2025; 13(8):845. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080845

Chicago/Turabian StyleLivieratos, Achilleas, Jamie M. Zeitzer, and Sotirios Tsiodras. 2025. "A Narrative Review on How Timing Matters: Circadian and Sleep Influences on Influenza Vaccine Induced Immunity" Vaccines 13, no. 8: 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080845

APA StyleLivieratos, A., Zeitzer, J. M., & Tsiodras, S. (2025). A Narrative Review on How Timing Matters: Circadian and Sleep Influences on Influenza Vaccine Induced Immunity. Vaccines, 13(8), 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13080845