Enablers and Barriers of COVID-19 Vaccination in the Philippines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

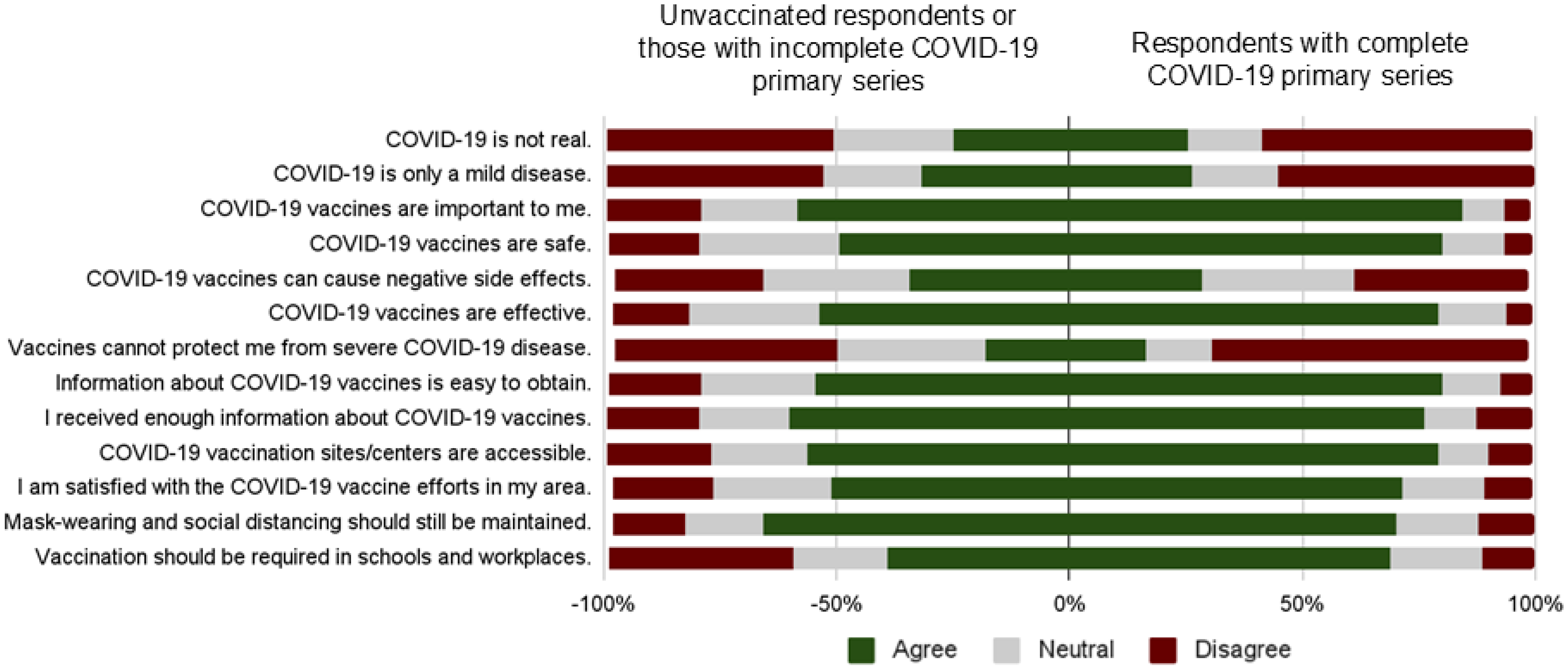

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease |

| aOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ASEAN | Association of South East Asian Nations |

| DOH | Department of Health |

| PHOC | Public Health Operations Center |

| MIMAROPA | Mindoro, Marinduque, Romblon, and Palawan |

| CHD | Centers for Health Development |

| RHUs | Rural Health Units |

| SAGE | Strategic Advisory Group of Experts |

| LRT | Likelihood ratio test |

| ORs | Odds ratio |

| Cis | Confidence intervals |

| UPMREB | University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board |

| LGUs | Local government units |

| HCWs | Healthcare workers |

References

- Department of Health—Philippines. COVID-19 Case Tracker. 2025. Available online: https://doh.gov.ph/diseases/covid-19/covid-19-case-tracker/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- WHO. WHO COVID-19 Dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/vaccines (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- DOH. The Philippine National Deployment and Vaccination Plan for COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://www.covidlawlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Phillipines_2020.01_The-Philippine-National-COVID-19-Vaccination-Deployment-Plan_EN.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Department of Health—Philippines. Department Memorandum No. 20210099: Interim Guidance on COVID-19 Case Management. August 2023. Available online: https://doh.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/dm2021-0099.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Republic of the Philippines. Proclamation No. 297, s. 2023: Lifting of the State of Public Health Emergency Throughout the Philippines Due to COVID-19. 21 July 2023. Available online: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2023/07/21/proclamation-no-297-s-2023/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- ASEAN Biodiaspora Virtual Center. COVID-19 and Mpox Situational Review in the ASEAN Region. 2023. Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/COVID-19-and-Mpox_Situational-Report_ASEAN-BioDiaspora-Regional-Virtual-Center_13Mar2023.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Tejero, L.M.S.; Seva, R.; Petelo Ilagan, B.; Almajose, K.L. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccination decision among Filipino adults. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzo, R.R.; Sami, W.; Alam, M.Z.; Acharya, S.; Jermsittiparsert, K.; Songwathana, K.; Pham, N.T.; Respati, T.; Faller, E.M.; Baldonado, A.M.; et al. Hesitancy in COVID-19 vaccine uptake and its associated factors among the general adult population: A cross-sectional study in six Southeast Asian countries. Trop. Med. Health 2022, 50, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.L.; Leung, A.W.Y.; Chung, O.M.H.; Chien, W.T. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccination uptake among community members in Hong Kong: A cross-sectional online survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gram, M.A.; Moustsen-Helms, I.R.; Valentiner-Branth, P.; Emborg, H.D. Sociodemographic differences in Covid-19 vaccine uptake in Denmark: A nationwide register-based cohort study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Gudi, N.; Nambiar, D.; Dumka, N.; Ahmed, T.; Sonawane, I.R.; Kotwal, A. A rapid review of evidence on the determinants of and strategies for COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in low- and middle-income countries. J. Glob. Health 2021, 11, 05027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Larson, H.J.; Hartigan-Go, K.; de Figueiredo, A. Vaccine confidence plummets in the Philippines following dengue vaccine scare: Why it matters to pandemic preparedness. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 15, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ulmido, M.L.; Reñosa, M.D.; Wachinger, J.; Endoma, V.; Landicho-Guevarra, J.; Landicho, J.; Bravo, T.A.; Aligato, M.; McMahon, S.A. Conflicting and complementary notions of responsibility in caregiver’s and Health Care Workers’ vaccination narratives in the Philippines. J. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 04016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. Vaccine Confidence Survey Question Bank. 2021. Available online: https://content.sph.harvard.edu/wwwhsph/sites/84/2021/07/CDC-Vaccine-Confidence-Survey-Question-Bank.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Domek, G.J.; O’Leary, S.T.; Bull, S.; Bronsert, M.; Contreras-Roldan, I.L.; Bolaños Ventura, G.A.; Kempe, A.; Asturias, E.J. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: Field testing the WHO SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy survey tool in Guatemala. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5273–5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Republic of the Philippines. Republic Act No. 11964: Institutionalizing the Automatic Income Classification of Provinces, Cities, and Municipalities. 26 October 2023. Available online: https://elibrary.judiciary.gov.ph/thebookshelf/showdocs/2/96834 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- StataCorp. Stata 18 Base Reference Manual; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, M.D.M.; Mohamed, N.A.; Solehan, H.M.; Ithnin, M.; Ariffien, A.R.; Isahak, I. Assessment of acceptability of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model among Malaysians-A qualitative approach. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Machida, M.; Nakamura, I.; Kojima, T.; Saito, R.; Nakaya, T.; Hanibuchi, T.; Takamiya, T.; Odagiri, Y.; Fukushima, N.; Kikuchi, H.; et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Japan during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2021, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bauer, S.; Contreras, S.; Dehning, J.; Linden, M.; Iftekhar, E.; Mohr, S.B.; Olivera-Nappa, A.; Priesemann, V. Relaxing restrictions at the pace of vaccination increases freedom and guards against further COVID-19 waves. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1009288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bardosh, K.; de Figueiredo, A.; Gur-Arie, R.; Jamrozik, E.; Doidge, J.; Lemmens, T.; Keshavjee, S.; Graham, J.E.; Baral, S. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: Why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e008684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Afrifa-Anane, G.F.; Larbi, R.T.; Addo, B.; Agyekum, M.W.; Kyei-Arthur, F.; Appiah, M.; Agyemang, C.O.; Sakada, I.G. Facilitators and barriers to COVID-19 vaccine uptake among women in two regions of Ghana: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mendoza, R.U.; Dayrit, M.M.; Alfonso, C.R.; Ong, M.M.A. Public trust and the COVID-19 vaccination campaign: Lessons from the Philippines as it emerges from the Dengvaxia controversy. Int. J. Health Plann Manag. 2021, 36, 2048–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Utami, A.; Margawati, A.; Pramono, D.; Nugraheni, A.; Pramudo, S.G. Determinant Factors of COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Adult and Elderly Population in Central Java, Indonesia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nomura, S.; Eguchi, A.; Yoneoka, D.; Kawashima, T.; Tanoue, Y.; Murakami, M.; Sakamoto, H.; Maruyama-Sakurai, K.; Gilmour, S.; Shi, S.; et al. Reasons for being unsure or unwilling regarding intention to take COVID-19 vaccine among Japanese people: A large cross-sectional national survey. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 14, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.F.W.; Woon, Y.L.; Leong, C.T.; Teh, H.S. Factors influencing acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine in Malaysia: A web-based survey. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2021, 12, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Okubo, R.; Yoshioka, T.; Ohfuji, S.; Matsuo, T.; Tabuchi, T. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Its Associated Factors in Japan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Purvis, R.S.; Moore, R.; Willis, D.E.; Hallgren, E.; McElfish, P.A. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine decision-making among hesitant adopters in the United States. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2114701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gehrau, V.; Fujarski, S.; Lorenz, H.; Schieb, C.; Blöbaum, B. The impact of health information exposure and source credibility on COVID-19 vaccination intention in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Massey, P.M.; Stimpson, J.P. Primary Source of Information About COVID-19 as a Determinant of Perception of COVID-19 Severity and Vaccine Uptake: Source of Information and COVID-19. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021, 36, 3088–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Williams, S.; Dienes, K. Public attitudes to COVID-19 vaccines: A qualitative study. MedRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denford, S.; Mowbray, F.; Towler, L.; Wehling, H.; Lasseter, G.; Amlôt, R.; Oliver, I.; Yardley, L.; Hickman, M. Exploration of attitudes regarding uptake of COVID-19 vaccines among vaccine hesitant adults in the UK: A qualitative analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Mudatsir, M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Southeast Asia: A cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, W.; Poon, P.K.; Kwok, K.O.; Chui, T.W.; Hung, P.H.Y.; Ting, B.Y.T.; Chan, D.C.; Wong, S.Y. Vaccine resistance and hesitancy among older adults who live alone or only with an older partner in community in the early stage of the fifth wave of COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, J.W.J.; Vaithilingam, S.; Nair, M.; Hwang, L.-A.; Musa, K.I. Key predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Malaysia: An integrated framework. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwary, M.M.; Bardhan, M.; Disha, A.S.; Hasan, M.; Haque, M.Z.; Sultana, R.; Hossain, M.R.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Alam, M.A.; Sallam, M. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among the adult population of Bangladesh using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprengholz, P.; Korn, L.; Eitze, S.; Felgendreff, L.; Siegers, R.; Goldhahn, L.; De Bock, F.; Huebl, L.; Böhm, R.; Betsch, C. Attitude toward a mandatory COVID-19 vaccination policy and its determinants: Evidence from serial cross-sectional surveys conducted throughout the pandemic in Germany. Vaccine 2022, 40, 7370–7377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 290 | 37.5 |

| 30–45 | 382 | 38.4 |

| 46–59 | 86 | 11.1 |

| ≥60 | 16 | 2.1 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 752 | 97 |

| Male | 20 | 2.6 |

| Civil status | ||

| Single | 25 | 3.2 |

| Married | 371 | 47.9 |

| Live-in | 327 | 42.2 |

| Separated | 14 | 1.8 |

| Widowed | 25 | 3.2 |

| Unspecified | 13 | 1.7 |

| Municipal Class | ||

| First Class Municipality | 263 | 33.9 |

| Second Class Municipality | 198 | 25.6 |

| Third Class Municipality | 260 | 33.6 |

| Fifth Class Municipality | 54 | 6.9 |

| Religion | ||

| Catholic | 649 | 83.7 |

| Other Christian denominations | 110 | 14.2 |

| Islam | 9 | 1.2 |

| Others | 6 | 0.8 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Elementary Level | 210 | 27.1 |

| High School Level | 458 | 59.1 |

| College Level | 107 | 13.8 |

| Employment status | ||

| Unemployed | 455 | 58.7 |

| Student | 6 | 0.8 |

| Pensioner | 5 | 0.6 |

| Self-employed | 75 | 9.7 |

| Employed | 233 | 30.1 |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated | 189 | 24.4 |

| Incomplete primary COVID-19 vaccine series | 26 | 3.3 |

| Complete primary series | 443 | 57.2 |

| Complete primary series with one booster dose | 79 | 10.2 |

| Complete primary series with two booster doses | 38 | 4.9 |

| Reasons for Vaccination Among Those Respondents Who Received at Least One Dose (n = 586) * | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Protection of self, family, and community | 545 | 93 |

| Influence of government-mandated regulations ** | 238 | 40.6 |

| Recommendation of family, friends, neighbors, etc. | 35 | 6 |

| Provision of incentives and rewards | 15 | 2.6 |

| Requirement for giving birth | 2 | 0.3 |

| Unspecified | 4 | 0.7 |

| Reasons for non-vaccination among unvaccinated respondents (n = 189) * | n | % |

| Distrust in vaccine safety/fear of side effects | 154 | 81.4 |

| Lack of time | 15 | 7.9 |

| Being pregnant | 14 | 7.4 |

| Doubt in vaccine effectiveness | 10 | 5.3 |

| Perception of COVID-19 vaccines being in experimental stage | 8 | 4.2 |

| Influence of religion/culture | 7 | 3.7 |

| Dislike of vaccine brand offered in the area | 6 | 3.2 |

| Perception that COVID-19 is not severe | 4 | 2.1 |

| Inaccessibility of vaccination sites | 2 | 1.1 |

| Others *** | 6 | 3.2 |

| Reasons for incomplete vaccination among respondents with incomplete primary vaccine series (n = 26) * | n | % |

| Fear of side effects | 6 | 23.1 |

| Low perceived need of vaccination | 3 | 1.2 |

| Inaccessibility of vaccination sites | 3 | 1.2 |

| Doubt in vaccine effectiveness | 3 | 1.2 |

| Difficulty in arranging schedules/long queues | 2 | 0.8 |

| Lack of time | 2 | 0.8 |

| Doubt in the quality of vaccine | 1 | 0.0 |

| Unvaccinated or Incomplete Primary Series (n = 215) | Complete Primary Series with or Without Boosters (n = 560) | Total (n = 775) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOH announcements | 100 (46.5%) | 404 (72.1%) | 504 (65%) |

| Mass media outlets | 139 (64.7%) | 315 (56.3%) | 454 (58.6%) |

| LGU/health center and healthcare workers | 69 (32.1%) | 288 (51.4%) | 357 (46.1%) |

| Social media | 82 (38.1%) | 198 (35.4%) | 280 (36.1%) |

| Online articles/pages of legitimate news outlets | 20 (9.3%) | 67 (12%) | 87 (11.2%) |

| International agencies (e.g., WHO and CDC) | 13 (6.1%) | 54 (9.6%) | 67 (8.7%) |

| Family and friends | 21 (9.8%) | 41 (7.3%) | 63 (8.1%) |

| Own reading/research | 11 (5.1%) | 33 (5.9%) | 44 (5.7%) |

| School | 10 (4.7%) | 22 (3.4%) | 32 (4.1%) |

| Church and religious leaders | 10 (4.7%) | 17 (3%) | 27 (3.5%) |

| Workplace | 2 (0.9%) | 11 (2%) | 13 (1.7%) |

| Celebrities and influencers | 2 (0.9%) | 8 (1.4%) | 10 (1.3%) |

| Tribal chief/leader | 3 (1.4%) | 5 (0.9%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Unspecified | 3 (1.4%) | 5 (0.9%) | 9 (1.2%) |

| No information | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.3%) |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics and Perceptions on COVID-19 Infection and COVID-19 Vaccination | n (%) † | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR Final Model †† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–29 | 290 (37.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 30–45 | 382 (38.4) | 2.37 (1.69–3.32) *** | 2.23 (1.49–3.35) *** |

| 46–59 | 86 (11.1) | 4.05 (2.11–7.79) *** | 2.84 (1.36–5.95) ** |

| ≥60 | 16 (2.1) | 1.97 (0.62–6.26) | 1.41 (0.33–6.06) |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Elementary level | 210 (27.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| High school level | 458 (59.1) | 2.27 (1.61–3.21) *** | 2.25 (1.47–3.43) *** |

| College level | 107 (13.8) | 4.89 (2.62–9.13) *** | 4.93 (2.37–19.27) ** |

| Employment status | |||

| Unemployed | 455 (58.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Student | 6 (0.8) | 2.51 (0.29–21.66) | 1.39 (0.12–15.81) |

| Pensioner | 5 (0.6) | 0.75 (0.12–4.55) | 0.21 (0.03–1.80) |

| Self-employed | 75 (9.7) | 1.48 (0.85–2.58) | 1.27 (0.64–2.46) |

| Employed | 233 (30.1) | 2.35 (1.59–3.47) *** | 1.99 (1.24–3.19) ** |

| Statements on COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| COVID-19 vaccines are safe. | |||

| Neutral | 139 (17.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Disagree | 75 (9.7) | 0.73 (0.41–1.28) | 0.93 (0.47–1.85) |

| Agree | 554 (71.5) | 3.71 (2.50–5.51) *** | 1.92 (1.16–3.18) * |

| Vaccines cannot protect me from severe COVID-19 disease. | |||

| Neutral | 146 (18.8) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Disagree | 485 (62.7) | 3.23 (2.19–4.78) *** | 2.23 (1.38–3.63) ** |

| Agree | 132 (17.0) | 2.08 (1.27–3.41) ** | 1.58 (0.86–2.88) |

| I am satisfied with COVID-19 vaccination efforts in my area. | |||

| Neutral | 122 (15.7) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Disagree | 82 (10.6) | 0.73 (0.42–1.28) | 1.34 (0.67–2.68) |

| Agree | 565 (72.9) | 2.94 (1.95–4.40) *** | 2.39 (1.14–4.06) ** |

| Vaccination should be required in schools and workplaces. | |||

| Neutral | 154 (19.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Disagree | 146 (18.8) | 0.28 (0.17–0.45) *** | 0.31 (0.18–0.55) *** |

| Agree | 470 (60.7) | 1.78 (1.17–2.72) * | 1.10 (0.65–1.86) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roxas, E.; Acacio-Claro, P.J.; Lota, M.M.; Abeleda, A.; Dalisay, S.N.; Landicho, M.; Fujimori, Y.; Rosuello, J.Z.; Kaufman, J.; Danchin, M.; et al. Enablers and Barriers of COVID-19 Vaccination in the Philippines. Vaccines 2025, 13, 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070719

Roxas E, Acacio-Claro PJ, Lota MM, Abeleda A, Dalisay SN, Landicho M, Fujimori Y, Rosuello JZ, Kaufman J, Danchin M, et al. Enablers and Barriers of COVID-19 Vaccination in the Philippines. Vaccines. 2025; 13(7):719. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070719

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoxas, Evalyn, Paulyn Jean Acacio-Claro, Maria Margarita Lota, Alvin Abeleda, Soledad Natalia Dalisay, Madilene Landicho, Yoshiki Fujimori, Jan Zarlyn Rosuello, Jessica Kaufman, Margaret Danchin, and et al. 2025. "Enablers and Barriers of COVID-19 Vaccination in the Philippines" Vaccines 13, no. 7: 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070719

APA StyleRoxas, E., Acacio-Claro, P. J., Lota, M. M., Abeleda, A., Dalisay, S. N., Landicho, M., Fujimori, Y., Rosuello, J. Z., Kaufman, J., Danchin, M., Belizario, V., Jr., & Vogt, F. (2025). Enablers and Barriers of COVID-19 Vaccination in the Philippines. Vaccines, 13(7), 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070719