How Immunization Information Systems Inform Age-Based HPV Vaccination Recommendations in the United States: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.2. Analysis

3. Results

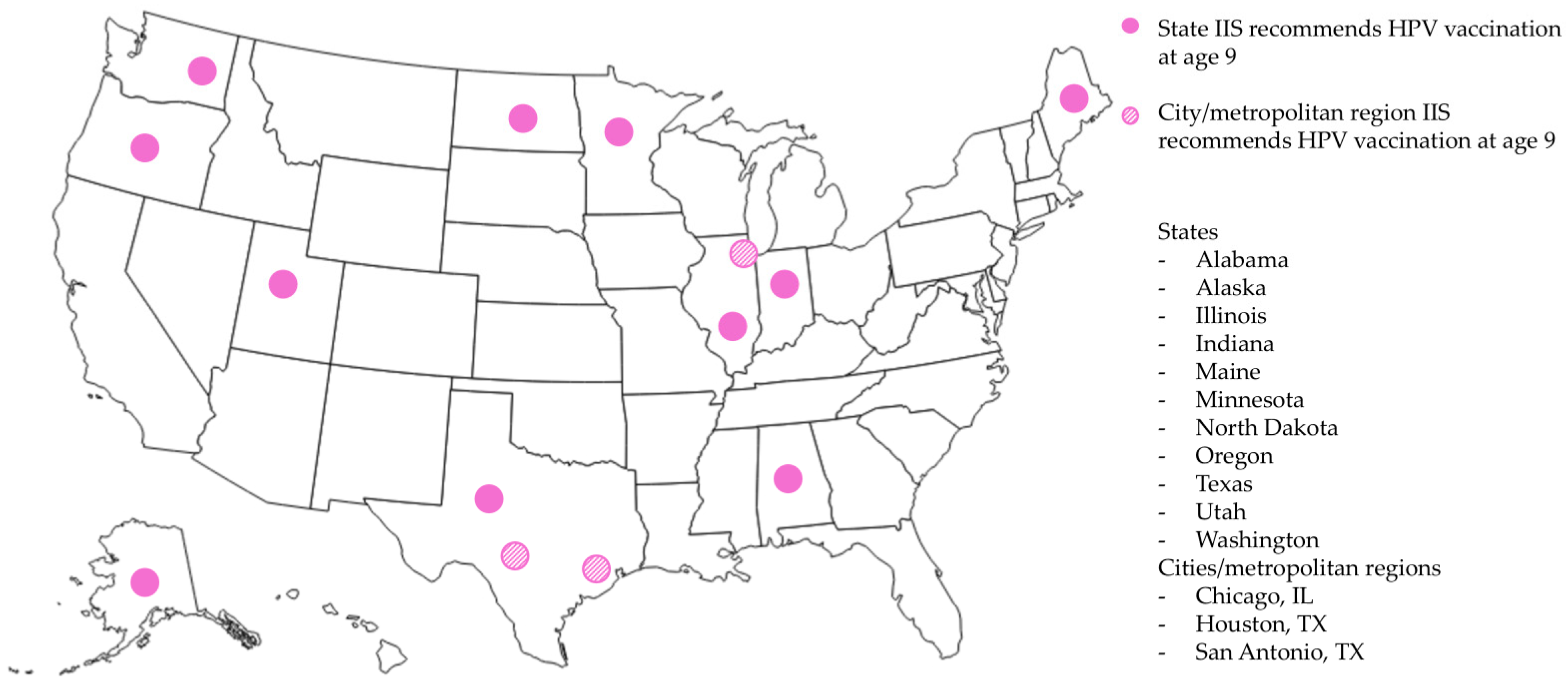

3.1. Survey of HPV Vaccination Forecasts

3.2. Focus Groups on IIS Implementation

3.2.1. Overview of Participating Jurisdictions

3.2.2. Customizability of IISs

“So they’ve really gone into a model of they need to evaluate this as a consortium as a whole and determine whether or not it’s a change that is going to benefit the whole consortium. So sometimes we don’t even have a say in that decision-making.”

“Wisconsin owns the base code and the license overall, but … we can make the changes that we need that make sense for our jurisdiction, but we need to be willing to share those with others.”

“We can make changes more quickly instead of a vendor. And the look and feel, and everything, is totally customizable.”

3.2.3. Decision-Making Around IIS Functions

“We do have close coordination with our Chapter of the AAP, with our Medicaid agencies, [the jurisdiction immunization coalition]. We have all of our Vaccines for Children (VFC) providers that have certain requirements in order to be VFC providers. We work closely with pharmacies as well. There are lots of different entities that we hear feedback from and engage with that help to inform policies and things.”

“There was lots of different advocacy groups coming out pushing 9. …Multiple people had come to us saying, hey, can this change? Providers were asking for it, which was pretty great.”

“I like standards, I like for the forecaster and for the system to behave according to ACIP recommendations pretty strictly. I personally wish the routine recommendation was at 9, that would clear up a lot of confusion.”

3.2.4. Changes to HPV Vaccination Forecast

“…we still saw significant gaps between HPV initiation and the Tdap and meningococcal vaccinations and also significant gaps between HPV completion and HPV initiation… That started broader conversations for us about what we can do to increase both initiation and completion rates. And I think that strategically we were also seeing it as starting earlier at age 9 gives providers more time to achieve completion by age 13.”

“We changed all our media and followed what the ACS was doing and changed our recommendation to 9. And we felt like, because we were recommending at 9, we should probably make that change [to the IIS]. And we actually did take it to the vaccine advisory board, and we had to get approval from them to do it.”

“So we really utilized our HPV Free Task Force to start to spread that message that people were allowed to start at 9. And because the actual recommendation from [the Department of Health] had not actually made that formal change in IIS, we really just shared this message as, this is an allowable thing.”

“But we said what if it [IIS] actually said that they’re due at 9 … would that make a difference? And we made sure that we had widespread support for it in our immunization community, and then it got brought to the vaccine advisory committee: let’s discuss this. Is there enough support behind this?”

“…How would we do the wording so that we don’t lose CDC funding, break some kind of contract? It’s just like, we don’t want to make an enemy, so how do we do this in concert with them, so that we have their approval? …So we were able to basically say we’re swimming with the CDC, we’re not going against them, we’re all going in the same direction.”

“…There can be some provider anxiety because it feels very different to them, but I think that our provider communication plan really acknowledges that difference in how to explain this to providers in a way that doesn’t feel like this is a massive switch but an expansion upon the work that they are already implementing.”

“…the culture has definitely shifted. I was in a meeting yesterday where everybody was talking about, ‘Oh, it’s a lot easier, and, you know, I didn’t think it would be.’”

“We have actually partnered with a provider who has been a long-time champion of vaccinating starting at age 9, well before any of this conversation, as it was up to a clinician’s discretion to be able to vaccinate at age 9. And so he has done a statewide webinar that was pretty well-received and is helping us think about how we frame out that clinician educational piece of implementation at a clinic level of the strategy of 9.”

“When we were made aware that we could have it as optional starting at age 9, because it used to say, “Not yet due until age 11,” … we talked about it, and we said, ‘Yeah, we definitely want to do that’….”

“Every state [that uses STC Health] has the option to override the CDC requirements or ACIP requirements….”

“…changing the earliest recommendation age for a vaccine schedule like that is super simple. I went in and moved it from 11 down to 9.”

“And of course, then there was the cost of publicizing it, making a training video, and making the dashboard. There are those downstream costs to promoting it at age 9, for sure.”

“We’d have to go through a pretty involved partner engagement process to look at the pros and cons of setting something in place like that here.”

3.2.5. Interoperability with EHR

“…we print the forecast [from the IIS] and put it on the clipboard when we go in the room, and we look at the actual IIS forecast more than we’re actually looking at our EHR. And there’s historical reasons for that, because the EHR, when it was getting built with the recommendations in the EHR sometimes weren’t accurate, and so it didn’t build a ton of trust for pediatricians in navigating that system initially.”

“So I talk to a lot of providers that look in both systems all of the time, maybe they don’t know that they have the functionality to view it in their EHR, maybe they don’t like the display, that [the IIS] is easier for them… So I would say there’s a lot of variation among workflows, too.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAP | American Academy of Pediatrics |

| ACIP | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices |

| ACS | American Cancer Society |

| CDC | U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| EHR | Electronic health records |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| IIS | Immunization information system |

| Tdap | Tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis vaccine |

References

- Martin, D.W.; Lowery, N.E.; Brand, B.; Gold, R.; Horlick, G. Immunization information systems: A decade of progress in law and policy. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2015, 21, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Immunization Finance Policies and Practices. Calling the Shots: Immunization Finance Policies and Practices; Appendix A. Public Health Services Act; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Groom, H.; Hopkins, D.P.; Pabst, L.J.; Murphy Morgan, J.; Patel, M.; Calonge, N.; Coyle, R.; Dombkowski, K.; Groom, A.V.; Kurilo, M.B.; et al. Immunization information systems to increase vaccination rates: A community guide systematic review. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2015, 21, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. IIS Policy and Legislation [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/iis/policy-legislation/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Sekar, K. Immunization Information Systems: Overview and Current Issues; CRS Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Immunization Managers. Awardee IIS and Vendors [Internet]. AIM Policy Maps. 2025. Available online: https://www.immunizationmanagers.org/resources/aim-policy-maps/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Decision Support for Immunization (CDSi) [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/iis/cdsi/index.html (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Dombkowski, K.J.; Patel, P.N.; Peng, H.K.; Cowan, A.E. The Effect of Electronic Health Record and Immunization Information System Interoperability on Medical Practice Vaccination Workflow. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2025, 16, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, M.S.; Natarajan, K.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Holleran, S.; Forney, K.; Aponte, A.; Vawdrey, D.K. Immunization data exchange with electronic health records. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woinarowicz, M.A.; Howell, M. The impact of electronic health record (EHR) interoperability on immunization information system (IIS) data quality. Online J. Public Health Inform. 2016, 8, e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrader, L.; Myerburg, S.; Larson, E. Clinical Decision Support for Immunization Uptake and Use in Immunization Health Information Systems. Online J. Public Health Inform. 2020, 12, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. December 10, 2014 Approval Letter—GARDASIL 9 [Internet]; U.S. Food & Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2014. Available online: https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20190425005410/https:/www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm426520.htm (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccine Recommendations [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/vaccination-considerations/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Increase the Proportion of Adolescents Who Get Recommended Doses of the HPV Vaccine—IID-08 [Internet]. Healthy People 2030. 2023. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/vaccination/increase-proportion-adolescents-who-get-recommended-doses-hpv-vaccine-iid-08 (accessed on 16 November 2013).

- Pingali, C.; Yankey, D.; Chen, M.; Elam-Evans, L.; Markowitz, L.E.; DeSisto, C.; Schillie, S.F.; Hughes, M.; Valier, M.R.; Stokley, S.; et al. National Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years—National Immunization Survey-Teen, United States, 2023. Morb. Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024, 73, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, N.L.; Biddell, C.B.; Rhodes, B.E.; Brewer, N.T. Provider communication and HPV vaccine uptake: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Prev. Med. 2021, 148, 106554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasserie, T.; Bendavid, E. Systematic identification and replication of factors associated with human papillomavirus vaccine initiation among adolescents in the United States using an environment-wide association study approach. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2022, 98, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, P.A.; Logie, C.H.; Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Baiden, P.; Tepjan, S.; Rubincam, C.; Doukas, N.; Asey, F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, K.; Kathe, N.; Sardana, P.; Yao, L.; Chen, Y.T.; Brewer, N.T. HPV vaccine initiation at 9 or 10 years of age and better series completion by age 13 among privately and publicly insured children in the US. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2161253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minihan, A.K.; Bandi, P.; Star, J.; Fisher-Borne, M.; Saslow, D.; Jemal, A. The association of initiating HPV vaccination at ages 9–10 years and up-to-date status among adolescents ages 13–17 years, 2016–2020. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2175555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarczyk, R.A.; Brandt, H.M. Descriptive epidemiology of age at HPV vaccination: Analysis using the 2020 NIS-Teen. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2204784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biancarelli, D.L.; Drainoni, M.L.; Perkins, R.B. Provider Experience Recommending HPV Vaccination Before Age 11 Years. J. Pediatr. 2020, 217, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, S.T.; Nyquist, A.C. Why AAP Recommends Initiating HPV Vaccination as Early as Age 9. AAP News [Internet]. 2019, pp. 8–9. Available online: https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/14942?autologincheck=redirected (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Saslow, D.; Andrews, K.S.; Manassaram-Baptiste, D.; Smith, R.A.; Fontham, E.T.H. Human papillomavirus vaccination 2020 guideline update: American Cancer Society guideline adaptation. Ca Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization Information Systems Annual Report (IISAR) [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/iis/annual-report-iisar/index.html (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Stefanos, R. Evidence to Recommendations Framework: Wording of the Age for Routine HPV Vaccination [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/acip/downloads/slides-2025-04-15-16/06-Stefanos-HPV-508.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Christensen, T.; Zorn, S.; Bay, K.; Treend, K.; Averette, C.; Rhodes, N. Effect of immunization registry-based provider reminder to initiate HPV vaccination at age 9, Washington state. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2274723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tietbohl, C.K.; Gur, D.; Duran, D.; Saville, A.; Clark, E.; Leary, S.O.; Albertin, C.; Beaty, B.; Vangala, S.; Szilagyi, P.G.; et al. Feasibility and Acceptability of Recommending HPV Vaccine at Ages 9–10 Years. Pediatrics 2025, 156, e2024069625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.Y.; Huang, Q.; Thompson, P.; Grabert, B.K.; Brewer, N.T.; Gilkey, M.B. Recommending Human Papillomavirus Vaccination at Age 9: A National Survey of Primary Care Professionals. Acad. Pediatr. 2022, 22, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagemann, C. Preventing Cancer with Earlier HPV Vaccination. Epic Share [Internet]. Available online: https://www.epicshare.org/share-and-learn/multi-site-hpv-vaccines-2 (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Richwine, C.; Strawley, C. Electronic Access to Immunization Information Among Primary Care Physicians [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.healthit.gov/data/data-briefs/electronic-access-immunization-information-among-primary-care-physicians (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Mansfield, L.N.; Vance, A.; Nikpour, J.A.; Gonzalez-Guarda, R.M. A Systematic Review of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Among, U.S. Adolescents. Res. Nurs. Health 2021, 44, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietro, V.G.; Maggioni, E.; Clavario, L.; Clerico, L.; Raso, E.; Marjin, C.; Parrini, A.; Carbone, M.; Fugazza, S.; Marchisio, A.; et al. Immunization information systems’ implementation and characteristics across the world: A systematic review of the literature. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Offers one age or date option for HPV vaccination | 6 (12) |

| Offers a range of age or date options for HPV vaccination | 43 (88) |

| Recommended age is 9 years | 14 (29) |

| Recommended age is 11 years | 33 (67) |

| Recommended age is 12 years | 1 (2) |

| Recommended age is 15 years | 1 (2) |

| Offers a minimum age or date (n = 42) | |

| Minimum age is 9 years | 40 (95) |

| Minimum age is 12 years | 1 (2) |

| Minimum age is 15 years | 1 (2) |

| Offers an overdue age or date (n = 34) | |

| Overdue age is 12 years | 1 (3) |

| Overdue age is 13 years | 30 (88) |

| Overdue age is 14 years | 1 (3) |

| Overdue age is 15 years | 2 (6) |

| Job Title | n * |

|---|---|

| IIS manager | 6 |

| Public health nurse consultant | 4 |

| Immunization branch director/deputy director/supervisor | 5 |

| Immunization coordinator | 4 |

| Public health educator/manager/director | 2 |

| CDC field designee/public health advisor | 2 |

| Epidemiologist | 2 |

| Data quality/quality improvement coordinator | 2 |

| Business analyst | 2 |

| Clinical application/services coordinator * | 2 |

| Pediatrician * | 2 |

| Cancer control program coordinator | 1 |

| Vaccine systems and support manager | 1 |

| Health promotion specialist | 1 |

| Age 9 Forecast | Age ≥ 11 Forecast | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| North Dakota | 78.5 (69.3 to 85.6) | Rhode Island | 80.4 (68.8 to 88.3) |

| Illinois—City of Chicago | 75.6 (65.0 to 83.8) | Massachusetts | 80.2 (72.8 to 86.0) |

| Texas—City of Houston | 68.1 (57.8 to 76.8) | Hawaii | 68.1 (59.7 to 75.5) |

| Oregon | 65.3 (56.3 to 73.4) | South Dakota | 65.6 (55.8 to 74.2) |

| Minnesota | 65.0 (56.4 to 72.6) | Colorado | 65.2 (57.0 to 72.6) |

| Illinois | 63.0 (56.8 to 68.9) | Michigan | 64.9 (54.3 to 74.2) |

| Alabama | 59.1 (51.1 to 66.7) | New Mexico | 64.3 (55.0 to 72.6) |

| Maine | 58.8 (50.7 to 66.5) | Wisconsin | 63.6 (55.6 to 70.9) |

| Washington | 58.6 (48.4 to 68.1) | Maryland | 63.6 (55.0 to 71.4) |

| Utah | 58.4 (47.4 to 68.6) | Iowa | 63.2 (53.2 to 72.2) |

| Indiana | 57.1 (47.5 to 66.3) | Connecticut | 63.1 (49.7 to 74.8) |

| Texas | 54.3 (45.7 to 62.6) | New York State | 61.7 (55.2 to 67.8) |

| Texas—Bexar County | 52.6 (43.5 to 61.5) | Vermont | 61.5 (50.3 to 71.7) |

| Alaska | 47.5 (37.7 to 57.6) | New Hampshire | 61.3 (51.9 to 70.0) |

| North Carolina | 61.2 (51.3 to 70.2) | ||

| Ohio | 60.6 (50.7 to 69.7) | ||

| Nebraska | 58.4 (48.8 to 67.5) | ||

| Florida | 58.4 (48.1 to 68.1) | ||

| Louisiana | 58.1 (48.5 to 67.1) | ||

| Arizona | 57.6 (48.2 to 66.5) | ||

| South Carolina | 56.3 (47.4 to 64.9) | ||

| California | 56.1 (45.7 to 66.0) | ||

| Virginia | 56 (44.5 to 66.9) | ||

| Tennessee | 54.2 (42.9 to 65.1) | ||

| Missouri | 50.4 (39.4 to 61.4) | ||

| Idaho | 50.0 (40.6 to 59.4) | ||

| West Virginia | 48.2 (40.2 to 56.3) | ||

| Wyoming | 47.9 (38.9 to 56.9) | ||

| U.S. Virgin Islands | 45.9 (28.5 to 64.4) | ||

| Kentucky | 44.5 (36.0 to 53.4) | ||

| Nevada | 44.1 (35.2 to 53.4) | ||

| New Jersey | 42.7 (34.9 to 50.9) | ||

| Georgia | 40.1 (29.3 to 52.0) | ||

| Oklahoma | 36.1 (27.6 to 45.6) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vielot, N.A.; Bucklin, I.K.; Westfall, K.; Kepka, D.; Zimet, G.; Zorn, S. How Immunization Information Systems Inform Age-Based HPV Vaccination Recommendations in the United States: A Mixed-Methods Study. Vaccines 2025, 13, 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070716

Vielot NA, Bucklin IK, Westfall K, Kepka D, Zimet G, Zorn S. How Immunization Information Systems Inform Age-Based HPV Vaccination Recommendations in the United States: A Mixed-Methods Study. Vaccines. 2025; 13(7):716. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070716

Chicago/Turabian StyleVielot, Nadja A., Isabelle K. Bucklin, Kristy Westfall, Deanna Kepka, Gregory Zimet, and Sherri Zorn. 2025. "How Immunization Information Systems Inform Age-Based HPV Vaccination Recommendations in the United States: A Mixed-Methods Study" Vaccines 13, no. 7: 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070716

APA StyleVielot, N. A., Bucklin, I. K., Westfall, K., Kepka, D., Zimet, G., & Zorn, S. (2025). How Immunization Information Systems Inform Age-Based HPV Vaccination Recommendations in the United States: A Mixed-Methods Study. Vaccines, 13(7), 716. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13070716