Opportunities to Increase Influenza Vaccine Uptake Among Pregnant Women: Insights from Surveys in 2013 and 2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Study Size

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Knowledge on Influenza Disease and the Influenza Vaccine

3.3. Attitude Toward the Influenza Vaccine

3.4. Influenza Vaccination and Non-Pharmaceutical Prevention Practices

3.5. Perceptions Influencing Influenza Vaccine Uptake Among Pregnant Participants

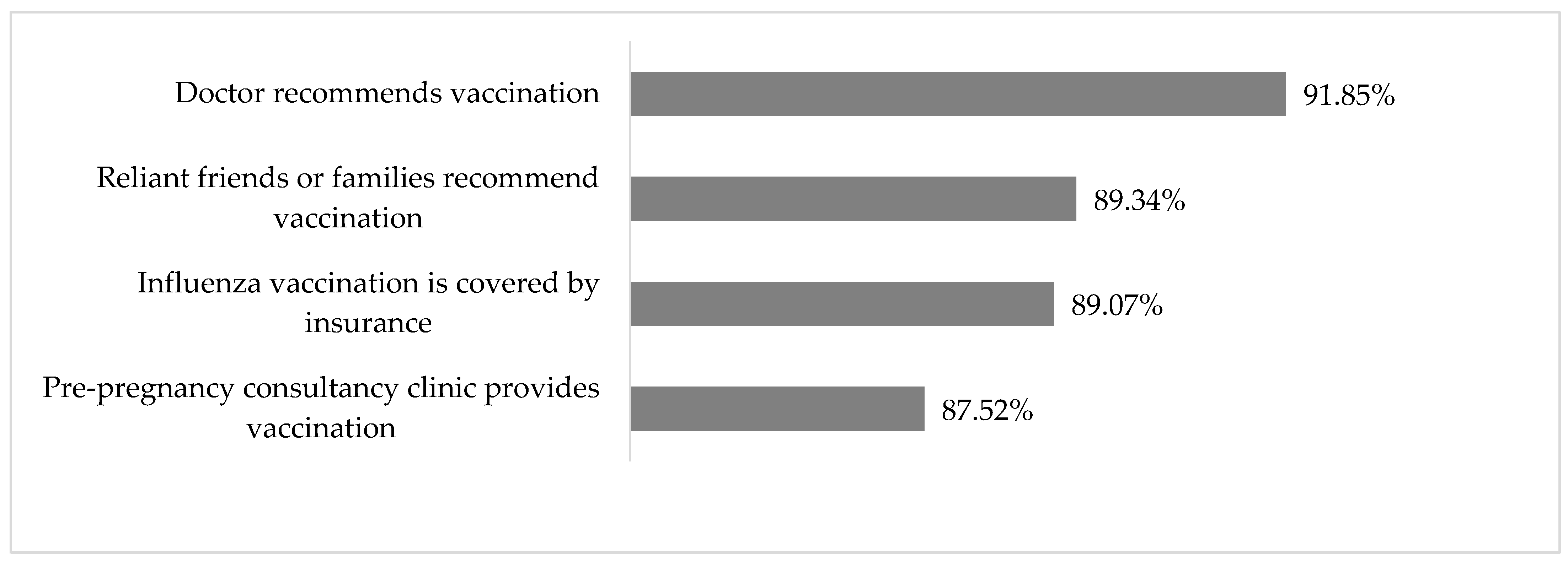

3.6. Intervention Needs

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Song, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Chen, L.; et al. Laboratory-confirmed influenza hospitalizations during pregnancy or the early postpartum period—Suzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China, 2018–2023. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Yan, W.; Du, M.; Tao, L.; Liu, J. The effect of influenza virus infection on pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 105, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fell, D.; Savitz, D.; Kramer, M.; Gessner, B.; Katz, M.; Knight, M.; Luteijn, J.; Marshall, H.; Bhat, N.; Gravett, M. Maternal influenza and birth outcomes: Systematic review of comparative studies. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 124, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.G.; Kwong, J.C.; Regan, A.K.; Katz, M.A.; Drews, S.J.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Klein, N.P.; Chung, H.; Effler, P.V.; Feldman, B.S.; et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Influenza-associated Hospitalizations During Pregnancy: A Multi-country Retrospective Test Negative Design Study, 2010–2016. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2019, 68, 1444–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irving, S.A.; Ball, S.W.; Booth, S.M.; Regan, A.K.; Naleway, A.L.; Buchan, S.A.; Katz, M.A.; Effler, P.V.; Svenson, L.W.; Kwong, J.C.; et al. A multi-country investigation of influenza vaccine coverage in pregnant individuals, 2010–2016. Vaccine 2021, 39, 7598–7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirve, S.; Lambach, P.; Paget, J.; Vandemaele, K.; Fitzner, J.; Zhang, W. Seasonal influenza vaccine policy, use and effectiveness in the tropics and subtropics—A systematic literature review. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2016, 10, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Yan, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, C.; Chen, L.; Lan, L.; Huang, C.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; et al. Global influenza vaccination rates and factors associated with influenza vaccination. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 125, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical guidelines for seasonal influenza vaccination in China (2023–2024). Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2023, 44, 1507–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Technical Guidelines for the Application of Seasonal Influenza Vaccine in China (2010–2011); Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L.; Yi, B.; Hao, X.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, R.; Greene, C. Increasing seasonal influenza vaccination among high risk groups in China: Do community healthcare workers have a role to play? Vaccine 2017, 35, 4060–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.; Kreuter, M. Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Henninger, M.L.; Irving, S.A.; Thompson, M.; Avalos, L.A.; Ball, S.W.; Shifflett, P.; Naleway, A.L. Factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnant women. J. Women’s Health (2002) 2015, 24, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Chen, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, K.; Pan, C. Seasonal Influenza Vaccination and influencing Factors in 2417 Pregnant Women in Shenzhen. J. Prev. Med. Chin. People’s Lib. Army 2018, 36, 168–170. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, S.; Bao, L.; Millman, A.J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Song, Y.; Cui, P.; Pang, Y.; et al. Incidence rates of influenza illness during pregnancy in Suzhou, China, 2015–2018. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2022, 16, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xie, R.; Yang, C.; Rainey, J.; Song, Y.; Greene, C. Identifying ways to increase seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women in China: A qualitative investigation of pregnant women and their obstetricians. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3315–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, G.J.; Sheedy, K.; Bursey, K.; Smith, T.M.; Basket, M. Promoting influenza vaccination: Insights from a qualitative meta-analysis of 14 years of influenza-related communications research by U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vaccine 2015, 33, 2741–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akmatova, R.; Dzhangaziev, B.; Ebama, M.S.; Otorbaeva, D. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) towards seasonal influenza and influenza vaccine among pregnant women in Kyrgyzstan: A cross-sectional study. Vaccine 2024, 42 (Suppl. S4), 125510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Kalhoro, S.; Khwaja, H.; Hussainyar, M.A.; Mehmood, J.; Qazi, M.F.; Abubakar, A.; Mohamed, S.; Khan, W.; Jehan, F.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards seasonal influenza vaccination among pregnant women and healthcare workers: A cross-sectional survey in Afghanistan. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2023, 17, e13101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriola, C.S.; Vasconez, N.; Bresee, J.; Ropero, A.M. Knowledge, attitudes and practices about influenza vaccination among pregnant women and healthcare providers serving pregnant women in Managua, Nicaragua. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3686–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditsungnoen, D.; Greenbaum, A.; Praphasiri, P.; Dawood, F.S.; Thompson, M.G.; Yoocharoen, P.; Lindblade, K.A.; Olsen, S.J.; Muangchana, C. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to seasonal influenza vaccine among pregnant women in Thailand. Vaccine 2016, 34, 2141–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Napolitano, P.; Angelillo, I.F. Seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnant women: Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in Italy. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erazo, C.E.; Erazo, C.V.; Grijalva, M.J.; Moncayo, A.L. Knowledge, attitudes and practices on influenza vaccination during pregnancy in Quito, Ecuador. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Greene, C.M.; Song, Y.; Zhang, R.; Rodewald, L.E.; Feng, L.; Millman, A.J. Review of the status and challenges associated with increasing influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women in China. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 16, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The General Office of the State Council. There Are More Than 4000 Prenatal Screening Institutions, and China’s Birth Defect Prevention and Treatment Network Is Constantly Improving. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/yaowen/liebiao/202407/content_6963680.htm (accessed on 20 July 2024).

| Time | Pregnant | Non-Pregnant | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of total participants | 2013 | 1673 | 401 | |

| 2023 | 2195 | 1171 | ||

| Median age (interquartile range), years | 2013 | 26 (23–29) | 24 (23–25) | |

| 2023 | 30 (27–33) | 29 (25–33) | 0.069 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Education, college or above | 2013 | 44% (741/1672) | 65% (260/399) | |

| 2023 | 74% (1632/2195) | 88% (1036/1171) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Household annual income ≥ CNY 250,000 | 2013 | 3% (47/1666) | 5% (21/401) | |

| 2023 | 27% (591/2195) | 19% (219/1171) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Median number of other persons living in the household (range) | 2013 | 3 (1–10) | 2 (1–6) | |

| 2023 | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–8) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Presence of underlying health condition | 2013 | 2.3% (39/1660) | 0.3% (1/399) | |

| 2023 | 2.6% (56/2195) | 2.4% (28/1171) | 0.867 | |

| p-value | 0.768 | 0.012 | ||

| BMI before pregnancy, mean ± standard deviation | 2013 | 20.9 ± 3.28 | 20.3 ± 2.48 | |

| 2023 | 22.4 ± 3.72 | 21.9 ± 3.86 | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Time | Pregnant | Non-Pregnant | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of influenza | ||||

| Know the main symptoms of influenza, including both fever and cough | 2013 | 91% (1525/1673) | 88% (351/401) | |

| 2023 | 95% (2093/2195) | 98% (1142/1171) | 0.003 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Know at least one of the routes by which influenza spreads, including coughing and indirect contact through hands | 2013 | 98% (1640/1673) | 96% (384/401) | |

| 2023 | 99% (2184/2195) | 100% (1169/1171) | 0.238 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Know at least one of the measures used to prevent influenza, including vaccination and non-pharmaceutical interventions | 2013 | 97% (1619/1673) | 85% (342/401) | |

| 2023 | 99% (2177/2195) | 99% (1162/1171) | 1.000 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Know that influenza and colds are different diseases | 2013 | 35% (583/1673) | 37% (148/401) | |

| 2023 | 49% (1076/2195) | 42% (495/1171) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.068 | ||

| Influenza can cause severe complications | 2013 | 80% (1335/1673) | 92% (368/401) | |

| 2023 | 62% (1351/2195) | 77% (899/1171) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Influenza can cause hospitalization | 2013 | 75% (1256/1673) | 92% (367/401) | |

| 2023 | 65% (1427/2195) | 78% (917/1171) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Influenza can cause death | 2013 | 63% (1059/1673) | 73% (294/401) | |

| 2023 | 49% (1079/2195) | 70% (824/1171) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.289 | ||

| Influenza during pregnancy may result in miscarriage/stillbirth | 2013 | 13% (213/1673) | 3% (11/401) | |

| 2023 | 44% (969/2195) | 52% (604/1171) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Influenza during pregnancy may lead to abnormal fetal development | 2013 | 28% (473/1673) | 22% (88/401) | |

| 2023 | 50% (1095/2195) | 55% (643/1171) | 0.006 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Knowledge of the influenza vaccine | ||||

| Self-report “ever heard” of the influenza vaccine | 2013 | 56% (939/1673) | 55% (222/401) | |

| 2023 | 57% (1261/2195) | 78% (914/1171) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | 0.430 | <0.001 | ||

| The data below represent those who ever heard of the influenza vaccine | ||||

| Know to get the influenza vaccine annually | 2013 | 39% (366/939) | 49% (109/222) | |

| 2023 | 33% (421/1261) | 41% (373/914) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | 0.043 | 0.030 | ||

| Know September–November is the time to get the influenza vaccine in Suzhou | 2013 | 14% (134/939) | 6% (14/222) | |

| 2023 | 12% (153/1261) | 20% (180/914) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | 0.008 | <0.001 | ||

| Know that pregnant women or those planning pregnancy constitute a priority group who should receive the influenza vaccine | 2013 | 12% (109/939) | 6% (13/222) | |

| 2023 | 20% (257/1261) | 25% (226/914) | 0.019 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Know community health centers are the location for influenza vaccination in Suzhou | 2013 | 34% (317/939) | 10% (22/222) | |

| 2023 | 66% (832/1261) | 73% (663/914) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Attitude regarding influenza vaccination | ||||

| Think the influenza vaccine works well or works sometimes | 2013 | 91% (851/939) | 84% (186/222) | |

| 2023 | 76% (960/1261) | 82% (750/914) | 0.001 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.612 | ||

| Think the influenza vaccine is safe or very safe | 2013 | 64% (601/939) | 64% (142/222) | |

| 2023 | 69% (867/1261) | 81% (744/914) | <0.001 | |

| p-value | 0.022 | <0.001 | ||

| Time | Pregnant | Non-Pregnant | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey respondent vaccinated with the influenza vaccine in the past 12 months | 2013 | 0.6% (10/1673) * | 0.0% (0/401) | ||

| 2023 | 1.9% (42/2195) * | 5.3% (62/1171) | <0.001 | ||

| p-value | 0.001 * | <0.001 | |||

| Family members vaccinated with the influenza vaccine in the past 12 months | 2013 | 8% (127/1673) | 1% (5/401) | ||

| 2023 | 7% (150/2195) | 13% (147/1171) | <0.001 | ||

| p-value | 0.400 | <0.001 | |||

| Large chance of being willing or almost certainly willing to receive an influenza vaccine while pregnant (among participants who had ever heard of the influenza vaccine) | 2013 | 9% (87/939) | 3% (7/222) | ||

| 2023 | 4% (45/1261) | 9% (86/914) | <0.001 | ||

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.004 | |||

| Among participants with a family member who had a fever and cough | |||||

| Try to avoid close contact with patient | 2013 | 25% (86/349) | 11% (10/92) | ||

| 2023 | 87% (680/781) | 88% (462/527) | 0.815 | ||

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Increase hand-washing frequency | 2013 | 10% (36/349) | 0% (0/92) | ||

| 2023 | 76% (591/781) | 76% (402/527) | 0.852 | ||

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Wear a mask | 2013 | 6% (22/349) | 0% (0/92) | ||

| 2023 | 82% (637/781) | 81% (427/527) | 0.863 | ||

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Percentage (n/N) | |

|---|---|

| Perceived “very relevant” or “extremely relevant” reasons to receive an influenza vaccination | |

| I get sick with the flu more easily than other people my age. | 17 (213/1261) |

| My doctor has recommended that I get a flu vaccination before or during my pregnancy. | 27 (342/1261) |

| I am worried that flu will bring harm to my fetus. | 36 (455/1261) |

| I think flu is high-risk for pregnant participants. | 29 (360/1261) |

| It is good for my family members. | 12 (148/1261) |

| Perceived “very relevant” or “extremely relevant” reasons not to receive an influenza vaccination | |

| I had a severe reaction following a prior vaccination. | 20 (245/1219) |

| I had concerns about side effects. | 15 (187/1219) |

| I had concerns about getting the flu from the flu shot. | 9 (108/1219) |

| I think flu vaccines do not work. | 9 (112/1219) |

| Flu vaccination is not needed. | 9 (107/1219) |

| I’m allergic to the vaccine. | 20 (238/1219) |

| Flu is not a very serious illness. | 11 (131/1219) |

| I do not have chances to have contact with people who get the flu. | 8 (97/1219) |

| I had had the flu earlier in the season. | 8 (100/1219) |

| Pregnant N = 2195 | Non-Pregnant N = 1171 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| What influenza-related knowledge and information do you want? | |||

| Prevention and control methods | 83 (1817) | 81 (946) | 0.165 |

| Transmission route | 80 (1759) | 78 (913) | 0.151 |

| Harm | 77 (1690) | 78 (916) | 0.441 |

| Characteristics of transmission | 76 (1673) | 77 (898) | 0.794 |

| Treatment methods | 71 (1567) | 73 (860) | 0.221 |

| What influenza vaccine-related knowledge and information do you want to receive? | |||

| Side effects | 84 (1852) | 83 (969) | 0.242 |

| Vaccination contraindications | 83 (1829) | 86 (1006) | 0.056 |

| Effectiveness of the vaccine | 77 (1682) | 77 (902) | 0.827 |

| Vaccination time and location | 73 (1607) | 78 (910) | 0.005 |

| Vaccination policy (e.g., priority populations) | 51 (1130) | 59 (687) | <0.001 |

| How do you hope to access knowledge about flu prevention? | |||

| Networks | 79 (1744) | 84 (978) | 0.005 |

| TV | 55 (1215) | 62 (721) | 0.001 |

| Doctor | 47 (1039) | 48 (567) | 0.573 |

| Family/friends | 37 (807) | 38 (442) | 0.601 |

| Broadcast | 35 (772) | 47 (552) | <0.001 |

| Newspapers/magazines | 27 (589) | 37 (434) | <0.001 |

| Billboards/manuals | 24 (526) | 30 (349) | <0.001 |

| Others | 1 (16) | 1 (9) | 1.000 |

| How do you access knowledge about flu prevention? | |||

| Networks, Internet | 78 (1718) | 81 (948) | 0.074 |

| TV | 63 (1381) | 69 (806) | 0.001 |

| Family/friends | 51 (1121) | 51 (598) | 1.000 |

| Doctor | 36 (797) | 48 (559) | <0.001 |

| Broadcast | 35 (766) | 49 (574) | <0.001 |

| Newspapers/magazines | 24 (534) | 39 (455) | <0.001 |

| Billboards/manuals | 18 (396) | 24 (283) | <0.001 |

| Others | 1 (22) | 1 (7) | 0.311 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wang, R.; Bao, L.; Liu, C.; Cui, P.; Tan, Y.; Hang, H.; Pang, Y.; Xu, Q.; et al. Opportunities to Increase Influenza Vaccine Uptake Among Pregnant Women: Insights from Surveys in 2013 and 2023. Vaccines 2025, 13, 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13060589

Zhang Y, Hong W, Wang R, Bao L, Liu C, Cui P, Tan Y, Hang H, Pang Y, Xu Q, et al. Opportunities to Increase Influenza Vaccine Uptake Among Pregnant Women: Insights from Surveys in 2013 and 2023. Vaccines. 2025; 13(6):589. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13060589

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuanyuan, Wanting Hong, Rui Wang, Lin Bao, Cheng Liu, Pengwei Cui, Yayun Tan, Hui Hang, Yuanyuan Pang, Qian Xu, and et al. 2025. "Opportunities to Increase Influenza Vaccine Uptake Among Pregnant Women: Insights from Surveys in 2013 and 2023" Vaccines 13, no. 6: 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13060589

APA StyleZhang, Y., Hong, W., Wang, R., Bao, L., Liu, C., Cui, P., Tan, Y., Hang, H., Pang, Y., Xu, Q., Tian, G., Jiang, J., Zhang, S., & Chen, L. (2025). Opportunities to Increase Influenza Vaccine Uptake Among Pregnant Women: Insights from Surveys in 2013 and 2023. Vaccines, 13(6), 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13060589