The Evolution of Annual Immunization Recommendations Against Influenza in Italy: The Path to Precision Vaccination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

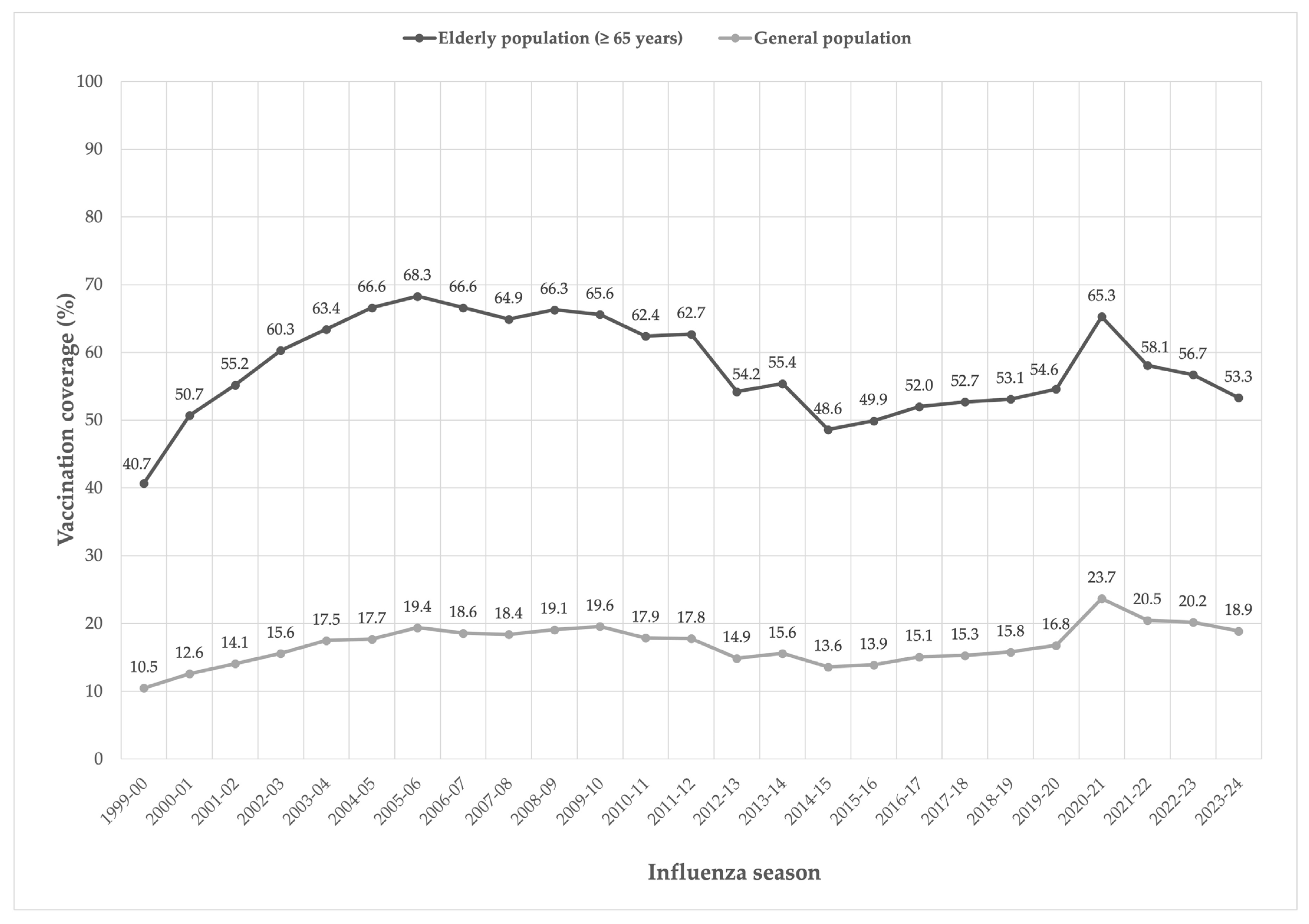

3. Results

3.1. Target Population for Vaccination

3.2. Vaccines Available for Use

3.3. Indications of Use

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Influenza (Seasonal). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Influenza Strategy 2019–2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241515320 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Factsheet About Seasonal Influenza. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/seasonal-influenza/facts/factsheet (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Epicentro. Influenza. General Information. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/influenza/influenza (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Hayward, A.C.; Fragaszy, E.B.; Bermingham, A.; Wang, L.; Copas, A.; Edmunds, W.J.; Ferguson, N.; Goonetilleke, N.; Harvey, G.; Kovar, J.; et al. Comparative community burden and severity of seasonal and pandemic influenza: Results of the Flu Watch cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- People at Increased Risk for Flu Complications. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/highrisk/index.htm (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Boccalini, S.; Bechini, A. Assessment of Epidemiological Trend of Influenza-Like Illness in Italy from 2010/2011 to 2023/2024 Season: Key Points to Optimize Future Vaccination Strategies against Influenza. Vaccines 2024, 12, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E. Influenza. In The Pink Book, 14th ed.; CDC: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021; Chapter 12. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/pinkbook/hcp/table-of-contents/chapter-12-influenza.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/flu.html (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Boccalini, S.; Bechini, A.; Innocenti, M.; Sartor, G.; Manzi, F.; Bonanni, P.; Panatto, D.; Lai, P.L.; Zangrillo, F.; Rizzitelli, E.; et al. La vaccinazione universale dei bambini contro l’influenza con il vaccino Vaxigrip Tetra® in Italia: Risultati di una valutazione di Health Technology Assessment (HTA) [The universal influenza vaccination in children with Vaxigrip Tetra® in Italy: An evaluation of Health Technology Assessment]. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2018, 59 (Suppl. S1), E1–E86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- SItI; SIP; FIMP; FIMG; SIMG. Vaccine Calendar for Life, 2025. V Edition. [Italian] Calendario Vaccinale per la vita. Available online: https://www.simg.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/calendario-per-la-vita-2025.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Bonanni, P.; Boccalini, S.; Zanobini, P.; Dakka, N.; Lorini, C.; Santomauro, F.; Bechini, A. The appropriateness of the use of influenza vaccines: Recommendations from the latest seasons in Italy. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2024–2025. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2024&codLeg=100738&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/new/it/tema/influenza/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2013–2014. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=0&codLeg=46769&parte=1%20&serie= (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2014–2015. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=0&codLeg=49871&parte=1%20&serie= (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2015–2016. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=0&codLeg=52703&parte=1%20&serie= (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2016–2017. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2016&codLeg=55586&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2017–2018. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf;jsessionid=JCEbZYZ6VGHBhyATrnouzg__.sgc4-prd-sal?anno=2017&codLeg=60180&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2018–2019. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2018&codLeg=64381&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2019–2020. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2019&codLeg=70621&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2020–2021. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2020&codLeg=74451&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2021–2022. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2021&codLeg=79647&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2022&codLeg=87997&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Prevention and Control: Recommendations for the Season 2023–2024. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2023&codLeg=93294&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Ministry of Health. Recommended Vaccinations for Women of Reproductive Age And pregnancy. Update November 2019. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/renderNormsanPdf?anno=2019&codLeg=71540&parte=1%20&serie=null (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- WHO Recommended Composition of Influenza Virus Vaccines for Use in the 2024–2025 Northern Hemisphere Influenza Season. 23 February 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/recommended-composition-of-influenza-virus-vaccines-for-use-in-the-2024-2025-northern-hemisphere-influenza-season (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Dipartimento della Programmazione e dell’Ordinamento del Servizio Sanitario Nazionale; Direzione Generale della Programmazione Sanitaria Ufficio III ex D.G.PROGS. Manuale di formazione per il governo clinico: Appropriatezza; 2012. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1826_allegato.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Appropriateness in Health Care Services. Report on a WHO Workshop, Koblenz, Germany 23–25 March 2000. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/108350 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Kheiraoui, F.; Cadeddu, C.; Quaranta, G.; Poscia, A.; Raponi, M.; de Waure, C.; Boccalini, S.; Pellegrino, E.; Bellini, I.; Pieri, L.; et al. Health Technology Assessment del vaccino antinfluenzale quadrivalente FLU-QIV (Fluarix Tetra®). Ital. J. Public Health 2015, 4, 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Di Pietro, M.L.; Poscia, A.; Specchia, M.L.; de Waure, C.; Zace, D.; Gasparini, R.; Amicizia, D.; Lai, P.L.; Panatto, D.; Arata, L.; et al. Valutazione di Health Technology Assessment (HTA) del vaccino antinfluenzale adiuvato nella popolazione anziana italiana. Ital. J. Public Health 2017, 6, 1–104. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrò, G.E.; Boccalini, S.; Del Riccio, M.; Ninci, A.; Manzi, F.; Bechini, A.; Bonanni, P.; Panatto, D.; Lai, P.L.; Amicizia, D.; et al. Valutazione di Health Technology Assessment (HTA) del vaccino antinfluenzale quadrivalente da coltura cellulare: Flucelvax Tetra. Ital. J. Public Health 2019, 8, 1–170. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrò, G.E.; Boccalini, S.; Bonanni, P.; Bechini, A.; Panatto, D.; Lai, P.L.; Amicizia, D.; Rizzo, C.; Ajelli, M.; Trentini, F.; et al. Valutazione di Health Technology Assessment (HTA) del vaccino antinfluenzale quadrivalente adiuvato: Fluad Tetra. Ital. J. Public Health 2021, 10, 1–168. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti, A.; Rumi, F.; Basile, M.; Orsini, F.; Gualano, M.R.; Bert, F.; Orsi, A.; Refolo, P.; Sacchini, D.; Casini, M.; et al. Report HTA del vaccino quadrivalente ad alto dosaggio (QIV-HD) EFLUELDA® per la prevenzione dell’influenza stagionale e delle sue complicanze nella popolazione over 65. Ital. J. Public Health 2021, 10, 1–170. [Google Scholar]

- Boccalini, S.; Pariani, E.; Calabrò, G.E.; De Waure, C.; Panatto, D.; Amicizia, D.; Lai, P.L.; Rizzo, C.; Amodio, E.; Vitale, F.; et al. Health Technology Assessment (HTA) dell’introduzione della vaccinazione antinfluenzale per la popolazione giovanile italiana con il vaccino Fluenz Tetra®. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2021, 62 (Suppl. S1), E1–E118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, G.E.; Boccalini, S.; Bechini, A.; Panatto, D.; Domnich, A.; Lai, P.L.; Amicizia, D.; Rizzo, C.; Pugliese, A.; Di Pietro, M.L.; et al. L’Health Technology Assessment come strumento value based per la valutazione delle tecnologie sanitarie. Reassessment del vaccino antinfluenzale quadrivalente da coltura cellulare: Flucelvax Tetra® 2.0. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63 (Suppl. S1), E1–E138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iob, A.; Brianti, G.; Zamparo, E.; Gallo, T. Evidence of increased clinical protection of an MF-59-adjuvant influenza vaccine compared to a non adjuvant vaccine among elderly residents of long term care facilities in Italy. Epidemiol. Infect. 2005, 133, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansaldi, F.; Zancolli, M.; Durando, P.; Montomoli, E.; Sticchi, L.; Del Giudice, G.; Icardi, G. Antibody response against heterogeneous circulating influenza virus strains elicited by MF59- and non-adjuvanted vaccines during seasons with good or partial matching between vaccine strain and clinical isolates. Vaccine 2010, 28, 4123–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannino, S.; Villa, M.; Apolone, G.; Weiss, N.S.; Groth, N.; Aquino, I.; Boldori, L.; Caramaschi, F.; Gattinoni, A.; Malchiodi, G.; et al. Effectiveness of adjuvanted influenza vaccination in elderly subjects in Northern Italy. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 176, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilloni, B.; Neri, M.; Lepri, E.; Iorio, A.M. Cross-reactive antibodies in middle-aged and elderly volunteers after MF59-adjuvanted subunit trivalent influenza vaccine against B viruses of the B/Victoria or B/Yamagata lineages. Vaccine 2009, 27, 4099–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Buynder, P.G.; Konrad, S.; Van Buynder, J.L.; Brodkin, E.; Krajden, M.; Ramler, G.; Bigham, M. The comparative effectiveness of adjuvanted and unadjuvanted trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) in the elderly. Vaccine 2013, 31, 6122–6128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira-Iglesias, A.; López-Labrador, F.X.; Baselga-Moreno, V.; Tortajada-Girbés, M.; Mollar-Maseres, J.; Carballido-Fernández, M.; Schwarz-Chavarri, G.; Puig-Barberà, J.; Díez-Domingo, J. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza in hospitalised adults aged 60 years or older, Valencia Region, Spain, 2017/18 influenza season. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebody, R.; Whitaker, H.; Zhao, H.; Andrews, N.; Ellis, J.; Donati, M.; Zambon, M. Protection provided by influenza vaccine against influenza-related hospitalisation in ≥65 year olds: Early experience of introduction of a newly licensed adjuvanted vaccine in England in 2018/19. Vaccine 2020, 38, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pebody, R.G.; Whitaker, H.; Ellis, J.; Andrews, N.; Marques, D.F.P.; Cottrell, S.; Reynolds, A.J.; Gunson, R.; Thompson, C.; Galiano, M.; et al. End of season influenza vaccine effectiveness in primary care in adults and children in the United Kingdom in 2018/19. Vaccine 2020, 38, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondy, M.; Larrauri, A.; Casado, I.; Alfonsi, V.; Pitigoi, D.; Launay, O.; Syrjänen, R.K.; Gefenaite, G.; Machado, A.; Vučina, V.V.; et al. 2015/16 seasonal vaccine effectiveness against hospitalisation with influenza a(H1N1)pdm09 and B among elderly people in Europe: Results from the I-MOVE+ project. Eurosurveillance 2017, 22, 30580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartvickson, R.; Cruz, M.; Ervin, J.; Brandon, D.; Forleo-Neto, E.; Dagnew, A.F.; Chandra, R.; Lindert, K.; Mateen, A.A. Non-inferiority of mammalian cell-derived quadrivalent subunit influenza virus vaccines compared to trivalent subunit influenza virus vaccines in healthy children: A phase III randomized, multicenter, double-blind clinical trial. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 41, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bart, S.; Cannon, K.; Herrington, D.; Mills, R.; Forleo-Neto, E.; Lindert, K.; Abdul Mateen, A. Immunogenicity and safety of a cell culture- based quadrivalent influenza vaccine in adults: A Phase III, double-blind, multicenter, randomized, non-inferiority study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 2278–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruxvoort, K.J.; Luo, Y.; Ackerson, B.; Tanenbaum, H.C.; Sy, L.S.; Gandhi, A.; Tseng, H.F. Comparison of vaccine effectiveness against influenza hospitalization of cell-based and egg-based influenza vaccines, 2017–2018. Vaccine 2019, 37, 5807–5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N.P.; Fireman, B.; Goddard, K.; Zerbo, O.; Asher, J.; Zhou, J.; King, J.; Lewis, N. Vaccine effectiveness of cell-culture relative to egg-based inactivated influenza vaccine during the 2017−18 influenza season. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.T.; Cheng, C.; Petrie, J.G.; Alyanak, E.; Gaglani, M.; Middleton, D.B.; Ghamande, S.; Silveira, F.P.; Murthy, K.; Zimmerman, R.K.; et al. Low Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Against A(H3N2)-Associated Hospitalizations in 2016−2017 and 2017−2018 of the Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN). J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, 2062–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.H.; Lam, G.K.L.; Shin, T.; Kim, J.; Krishnan, A.; Greenberg, D.P.; Chit, A. Efficacy and effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccination for older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2018, 17, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.K.H.; Lam, G.K.L.; Yin, J.K.; Loiacono, M.M.; Samson, S.I. High-dose influenza vaccine in older adults by age and seasonal characteristics: Systematic review and meta-analysis update. Vaccine X 2023, 14, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- DiazGranados, C.A.; Dunning, A.J.; Kimmel, M.; Kirby, D.; Treanor, J.; Collins, A.; Pollak, R.; Christoff, J.; Earl, J.; Landolfi, V.; et al. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasubramani, G.K.; Choi, W.S.; Nowalk, M.P.; Zimmerman, R.K.; Monto, A.S.; Martin, E.T.; Belongia, E.A.; McLean, H.Q.; Gaglani, M.; Murthy, K.; et al. Relative effectiveness of high dose versus standard dose influenza vaccines in older adult outpatients over four seasons, 2015−16 to 2018−19. Vaccine 2020, 38, 6562–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.D.; Beacham, L.; Martin, E.T.; Talbot, H.K.; Monto, A.; Gaglani, M.; Middleton, D.B.; Silveira, F.P.; Zimmerman, R.K.; Alyanak, E.; et al. Relative and Absolute Effectiveness of High-Dose and Standard-Dose Influenza Vaccine Against Influenza-Related Hospitalization Among Older Adults-United States, 2015–2017. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021, 72, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, L.M.; Izikson, R.; Patriarca, P.; Goldenthal, K.L.; Muse, D.; Callahan, J.; Cox, M.M. Efficacy of recombinant influenza vaccine in adults 50 years of age or older. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2427–2436. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, R.K.; Dauer, K.; Clarke, L.; Nowalk, M.P.; Raviotta, J.M.; Balasubramani, G.K. Vaccine effectiveness of recombinant and standard dose influenza vaccines against outpatient illness during 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 calculated using a retrospective test-negative design. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2177461. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle, L.M.; Izikson, R.; Patriarca, P.A.; Goldenthal, K.L.; Muse, D.; Cox, M.M.J. Randomized comparison of immunogenicity and safety of quadrivalent recombinant versus inactivated influenza vaccine in healthy adults 18-49 years of age. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.P.Y.; Cohen, C.A.; Leung, N.H.L.; Fang, V.J.; Gangappa, S.; Sambhara, S.; Levine, M.Z.; Iuliano, A.D.; Perera, R.A.P.M.; Ip, D.K.M.; et al. Immunogenicity of standard, high-dose, MF59-adjuvanted, and recombinant-HA seasonal influenza vaccination in older adults. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Vaccine Against Influenza: WHO Position Paper–May 2022. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/354264/WER9719-eng-fre.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Recommendations by the Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO) at the Robert Koch Institute–2023. Available online: https://www.rki.de/EN/Topics/Infectious-diseases/Immunisation/STIKO/STIKO-recommendations/stiko-recommendations-node.html (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Australian Government. Department of Health and Aged Care. Statement on the Administration of Seasonal Influenza Vaccines in 2024. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-02/atagi-statement-on-the-administration-of-seasonal-influenza-vaccines-in-2024.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- National Immunisation Programme 2024, UK. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-flu-immunisation-programme-plan-2024-to-2025/national-flu-immunisation-programme-2024-to-2025-letter (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. Minute of the Meeting on 07 June 2023. Available online: https://app.box.com/s/iddfb4ppwkmtjusir2tc/file/1262409204637 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Izurieta, H.S.; Lu, M.; Kelman, J.; Lu, Y.; Lindaas, A.; Loc, J.; Pratt, D.; Wei, Y.; Chillarige, Y.; Wernecke, M.; et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccines Among US Medicare Beneficiaries Ages 65 Years and Older During the 2019–2020 Season. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e4251–e4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grohskopf, L.A.; Blanton, L.H.; Ferdinands, J.M.; Chung, J.R.; Broder, K.R.; Talbot, H.K. Prevention and Control of Seasonal Influenza with Vaccines: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023–2024 Influenza Season. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2023, 72, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI). Statement on Seasonal Influenza Vaccine for 2023–2024. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/vaccines-immunization/national-advisory-committee-immunization-statement-seasonal-influenza-vaccine-2023-2024.html (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Ministry of Health. Piano Nazionale Prevenzione Vaccinale 2023–2025. Available online: https://www.trovanorme.salute.gov.it/norme/dettaglioAtto.spring?id=95963&page=newsett (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Ministry of Health. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Data. Available online: https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/influenza/dettaglioContenutiInfluenza.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=679&area=influenza&menu=vuoto (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Boccalini, S.; Tacconi, F.M.; Lai, P.L.; Bechini, A.; Bonanni, P.; Panatto, D. Appropriateness and preferential use of different seasonal influenza vaccines: A pilot study on the opinion of vaccinating physicians in Italy. Vaccine 2019, 37, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellino, S.; Piovesan, C.; Bella, A.; Rizzo, C.; Pezzotti, P.; Ramigni, M. Determinants of vaccination uptake, and influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing deaths and hospital admissions in the elderly population; Treviso, Italy, 2014/2015-2016/2017 seasons. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Buja, A.; Grotto, G.; Taha, M.; Cocchio, S.; Baldo, V. Use of Information and Communication Technology Strategies to Increase Vaccination Coverage in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuurman, A.L.; Ciampini, S.; Vannacci, A.; Bella, A.; Rizzo, C.; Muñoz-Quiles, C.; Pandolfi, E.; Liyanage, H.; Haag, M.; Redlberger-Fritz, M.; et al. Factors driving choices between types and brands of influenza vaccines in general practice in Austria, Italy, Spain and the UK. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ecarnot, F.; Maggi, S.; Michel, J.P. Strategies to Improve Vaccine Uptake throughout Adulthood. Interdiscip. Top. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2020, 43, 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanza, T.E.; Paladini, A.; Marziali, E.; Gianfredi, V.; Blandi, L.; Signorelli, C.; Odone, A.; Ricciardi, W.; Damiani, G.; Cadeddu, C. Training needs assessment of European frontline health care workers on vaccinology and vaccine acceptance: A systematic review. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Capodici, A.; Montalti, M.; Soldà, G.; Salussolia, A.; La Fauci, G.; Di Valerio, Z.; Scognamiglio, F.; Fantini, M.P.; Odone, A.; Costantino, C.; et al. Influenza vaccination landscape in Italy: A comprehensive study through the OBVIOUS project lens. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2252250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holford, D.; Anderson, E.C.; Biswas, A.; Garrison, A.; Fisher, H.; Brosset, E.; Gould, V.C.; Verger, P.; Lewandowsky, S. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of challenges in vaccine communication and training needs: A qualitative study. BMC Prim. Care. 2024, 25, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Target Population of Influenza Vaccination Program | |

|---|---|

| Subjects at high risk of complications or hospitalizations related to influenza: |

|

| Subjects employed in public services of primary collective interest and categories of workers: |

|

| Personnel who, for work-related reasons, come into contact with animals that could serve as a source of infection from non-human influenza viruses: |

|

| Other categories: |

|

| Types of Vaccines Reported in the Annual Italian Circulars for the Prevention and Control of Influenza | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza Season | Inactivated Split or Subunit Vaccine | Virosome-Adjuvanted Trivalent Inactivated Influenza Vaccine | Adjuvanted Inactivated Vaccine (MF59) | Trivalent Inactivated Intradermal Vaccine (Split) | Cell-Based Vaccine | Live-Attenuated Vaccine | High-Dose Quadrivalent Split Inactivated Vaccine | Recombinant Quadrivalent Vaccine |

| 2013–2014 | TIV | VATIIV | aTIV | IDTIIV | ||||

| 2014–2015 | TIV o QIV | aTIV | IDTIIV | |||||

| 2015–2016 | TIV o QIV | aTIV | IDTIIV | TIVcc | ||||

| 2016–2017 | TIV o QIV | aTIV | IDTIIV | |||||

| 2017–2018 | TIV o QIV | aTIV | IDTIIV | |||||

| 2018–2019 | TIV o QIV | aTIV | ||||||

| 2019–2020 | TIV o QIV | aTIV | QIVcc | |||||

| 2020–2021 | TIV o QIV | aTIV | QIVcc | QIVhd | ||||

| 2021–2022 | QIV | aQIV | QIVcc | LAIV (quadrivalent) | QIVhd | rQIV | ||

| 2022–2023 | QIV | aQIV | QIVcc | LAIV (quadrivalent) | QIVhd | rQIV | ||

| 2023–2024 | QIV | aQIV | QIVcc | LAIV (quadrivalent) | QIVhd | rQIV | ||

| 2024–2025 | QIV | aQIV | QIQcc | LAIV (trivalent) | QIVhd | rQIV | ||

| Influenza Season | Age Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Months– 9 Years Old | 10–17 Years Old | 18–59 Years Old | 60–64 Years Old | ≥65 Years Old | |

| 2013–2014 | TIV VATIIV | TIV VATIIV | TIV VATIIV IDTIIV | TIV VATIIV IDTIIV | TIV VATIIV IDTIIV aTIV |

| 2014–2015 | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV IDTIIV | TIV or QIV IDTIIV | TIV or QIV aTIV |

| 2015–2016 | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV TIVcc | TIV or QIV IDTIIV TIVcc | TIV or QIV IDTIIV TIVcc aTIV |

| 2016–2017 | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV IDTIIV | TIV or QIV IDTIIV aTIV |

| 2017–2018 | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV IDTIIV | TIV or QIV IDTIIV aTIV |

| 2018–2019 | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV aTIV |

| 2019–2020 | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV QIVcc | TIV or QIV QIVcc | TIV or QIV QIVcc | TIV or QIV QIVcc aTIV |

| 2020–2021 | TIV or QIV | TIV or QIV QIVcc | TIV or QIV QIVcc | TIV or QIV QIVcc | TIV or QIV QIVcc aTIV QIVhd |

| 2021–2022 | QIV QIVcc (≥2 years) LAIV (≥2 years) | QIV QIVcc LAIV | QIV QIVcc rQIV | QIV QIVcc rQIV | QIV QIVcc rQIV QIVhd aQIV |

| 2022–2023 | QIV QIVcc (≥2 years) LAIV (≥2 years) | QIV QIVcc LAIV | QIV QIVcc rQIV QIVhd | QIV QIVcc rQIV QIVhd | QIV QIVcc rQIV QIVhd aQIV |

| 2023–2024 | QIV QIVcc (≥2 years) LAIV (≥2 years) | QIV QIVcc LAIV | QIV QIVcc rQIV | QIV QIVcc rQIV QIVhd | QIV QIVcc rQIV QIVhd aQIV |

| 2024–2025 | QIV QIVcc (≥2 years) LAIV (≥2 years) | QIV QIVcc LAIV | QIV QIVcc rQIV aQIV (≥50 years) | QIV QIVcc rQIV QIVhd aQIV | QIV QIVcc rQIV QIVhd aQIV |

| Target Population | Influenza Vaccines | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QIV | aQIV | rQIV | QIVhd | LAIV | QIVcc | |

| Subjects aged 65 years or older | A | R | A | R | A | |

| People in the 60–64 years age group | A | A | A | A | A | |

| Subjects aged between 50 years and 59 years who are included in the categories listed in Table 1 | A | A | A | A | ||

| Subjects aged between 18 years and 49 years who are included in the categories listed in Table 1 | A | A | A | |||

| Children aged between 7 and 17 years who are included in the categories listed in Table 1 | A | A | A | |||

| Children in the 2–6 years age group | A | A | A | |||

| Children in the 6 months–2 years age group | A | |||||

| Women who, at the beginning of the epidemic season, are in any trimester of pregnancy or the “postpartum” period | A | A | A | |||

| Reference | Authors | Type of Study | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| [50] | Lee JKH et al. (2018) | Systematic review | High-dose inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine is more effective than standard-dose trivalent influenza vaccine at reducing the clinical outcomes associated with influenza infection in adults ≥ 65. |

| [51] | Lee JKH et al. (2023) | Systematic review | High-dose inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine is more effective than standard-dose trivalent influenza vaccine at reducing influenza and associated serious outcomes in people aged ≥ 65 years, irrespective of age or characteristics of the influenza season. |

| [52] | DiazGranados CA et al. (2014) | Phase IIIb-IV, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled trial | Assessments of relative efficacy, effectiveness, safety, and immunogenicity were performed during the 2011–2012 and the 2012–2013 northern hemisphere influenza seasons. Among persons 65 years of age or older, high-dose inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine induced significantly higher antibody responses and provided better protection against laboratory-confirmed influenza illness than did standard-dose trivalent influenza vaccine. |

| [53] | Balasubramani GK et al. (2020) | Test-negative case–control study | US Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Network data from the 2015–2016 through 2018–2019 seasons were analyzed to determine relative vaccine effectiveness between high-dose inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine and standard-dose trivalent influenza vaccine among outpatients ≥ 65 years old presenting with acute respiratory illness. High-dose vaccine offered more protection against A/H3N2 and borderline significant protection against all influenza A infections requiring outpatient care during the 2015–2018 influenza. |

| [54] | Doyle JD et al. (2021) | Observational study | Hospitalized patients with acute respiratory illness were enrolled in an observational vaccine effectiveness study during the 2015–2016 and 2016–2017 influenza seasons. Enrolled patients were tested for influenza, and receipt of influenza vaccine by type was recorded. Effectiveness of standard-dose vaccine and high-dose vaccine was estimated using a test-negative design. High-dose vaccine offered greater effectiveness. |

| [58] | Li APY et al. (2021) | Randomized controlled trial | The cellular and antibody responses of standard-dose vaccines versus enhanced vaccines, MF59-adjuvanted, high-dose, and recombinant vaccines were compared in adults ≥ 65. Enhanced (high-dose and adjuvanted) influenza vaccines increase the polyfunctional CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell response. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boccalini, S.; de Waure, C.; Martorella, L.; Orlando, P.; Bonanni, P.; Bechini, A. The Evolution of Annual Immunization Recommendations Against Influenza in Italy: The Path to Precision Vaccination. Vaccines 2025, 13, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13040356

Boccalini S, de Waure C, Martorella L, Orlando P, Bonanni P, Bechini A. The Evolution of Annual Immunization Recommendations Against Influenza in Italy: The Path to Precision Vaccination. Vaccines. 2025; 13(4):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13040356

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoccalini, Sara, Chiara de Waure, Linda Martorella, Paolo Orlando, Paolo Bonanni, and Angela Bechini. 2025. "The Evolution of Annual Immunization Recommendations Against Influenza in Italy: The Path to Precision Vaccination" Vaccines 13, no. 4: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13040356

APA StyleBoccalini, S., de Waure, C., Martorella, L., Orlando, P., Bonanni, P., & Bechini, A. (2025). The Evolution of Annual Immunization Recommendations Against Influenza in Italy: The Path to Precision Vaccination. Vaccines, 13(4), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13040356