Vaccine Platform-Dependent Differential Impact on Microbiome Diversity: Potential Advantages of Protein Subunit Vaccines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental Model and Participant Details

2.1.1. NVX-CoV2373 Booster Cohort

2.1.2. BNT162b2 Booster Cohort

2.2. Sample Collection and Processing

2.3. Immunoassay for Quantitative Determination of Antibodies Against the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein

2.4. Microbiological Analysis

2.4.1. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Sequencing

2.4.2. DNA Analysis Pipeline

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. NVX-CoV2373 Booster Increases Gut Microbiome Alpha Diversity

3.2. Taxonomic and Functional Shifts Following NVX-CoV2373 Booster

3.3. Comparative Analysis with mRNA and Adenovirus Vector Vaccines

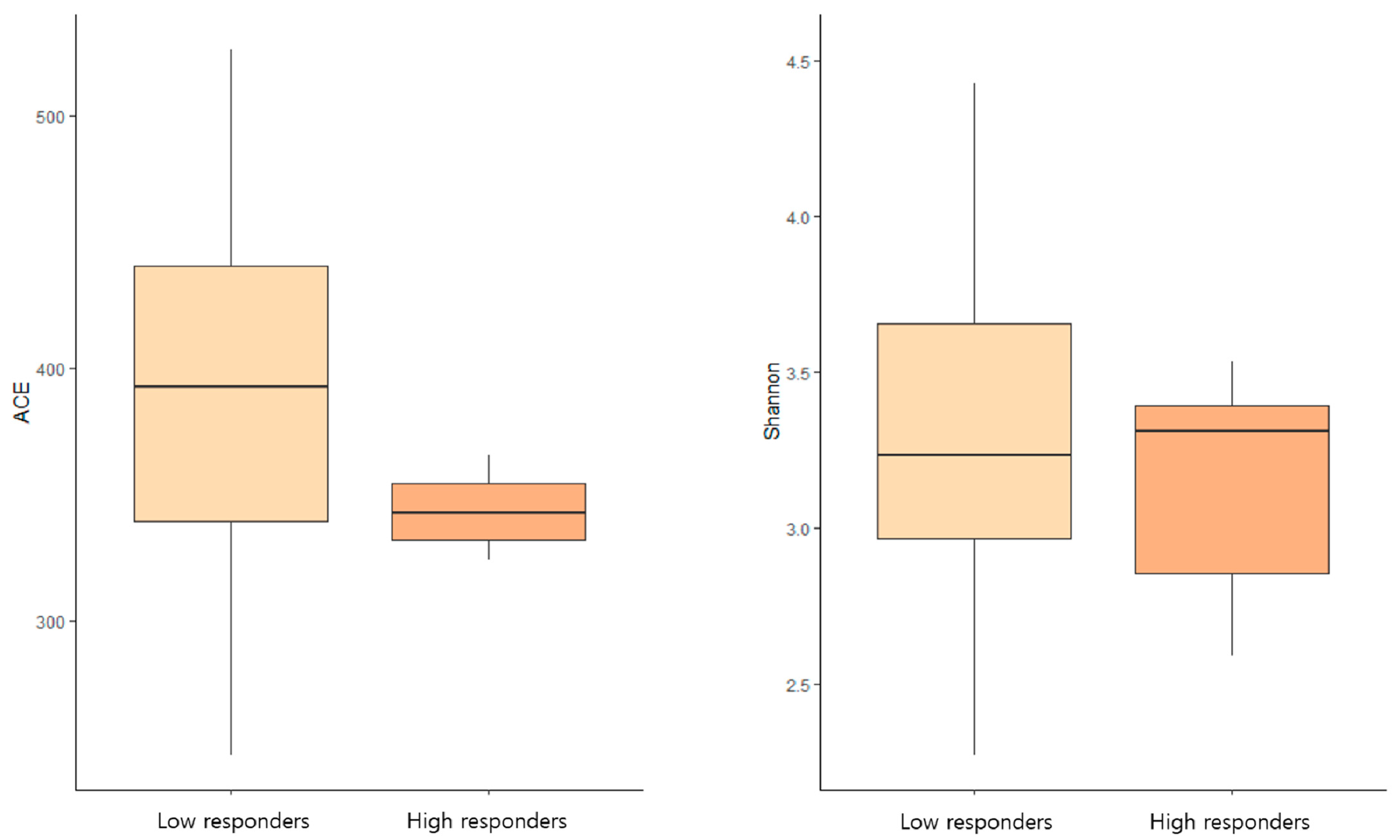

3.4. Microbiome Diversity and Humoral Immune Response

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Keech, C.; Albert, G.; Cho, I.; Robertson, A.; Reed, P.; Neal, S.; Plested, J.S.; Zhu, M.; Cloney-Clark, S.; Zhou, H.; et al. Phase 1–2 trial of a sars-cov-2 recombinant spike protein nanoparticle vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2320–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Y.; Choi, W.S.; Heo, J.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Jung, D.S.; Kim, S.W.; Park, K.H.; Eom, J.S.; Jeong, S.J.; Lee, J.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a sars-cov-2 recombinant protein nanoparticle vaccine (gbp510) adjuvanted with as03: A randomised, placebo-controlled, observer-blinded phase 1/2 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 51, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jae Kyu, L.; Ok Sarah, S. Coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19) vaccine platforms: How novel platforms can prepare us for future pandemics: A narrative review. J. Yeungnam Med. Sci. 2022, 39, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, S.E.; Olin, A.; Pulendran, B. The impact of the microbiome on immunity to vaccination in humans. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Z.; Ravindran, R.; Chassaing, B.; Carvalho, F.A.; Maddur, M.S.; Bower, M.; Hakimpour, P.; Gill, K.P.; Nakaya, H.I.; Yarovinsky, F.; et al. Tlr5-mediated sensing of gut microbiota is necessary for antibody responses to seasonal influenza vaccination. Immunity 2014, 41, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, V.C.; Armah, G.; Fuentes, S.; Korpela, K.E.; Parashar, U.; Victor, J.C.; Tate, J.; de Weerth, C.; Giaquinto, C.; Wiersinga, W.J.; et al. Significant correlation between the infant gut microbiome and rotavirus vaccine response in rural ghana. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 215, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagan, T.; Cortese, M.; Rouphael, N.; Boudreau, C.; Linde, C.; Maddur, M.S.; Das, J.; Wang, H.; Guthmiller, J.; Zheng, N.-Y.; et al. Antibiotics-driven gut microbiome perturbation alters immunity to vaccines in humans. Cell 2019, 178, 1313–1328.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, H.; Choi, B.K.; Han, Y.H.; Kim, J.H.; Gim, J.A.; Lim, S.; Noh, J.Y.; Cheong, H.J.; Kim, W.J.; Song, J.Y. Gut microbiota as a potential key to modulating humoral immunogenicity of new platform covid-19 vaccines. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, D.J.; Benson, S.C.; Lynn, M.A.; Pulendran, B. Modulation of immune responses to vaccination by the microbiota: Implications and potential mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stertman, L.; Palm, A.E.; Zarnegar, B.; Carow, B.; Lunderius Andersson, C.; Magnusson, S.E.; Carnrot, C.; Shinde, V.; Smith, G.; Glenn, G.; et al. The matrix-m™ adjuvant: A critical component of vaccines for the 21st century. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2023, 19, 2189885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 1964, 187, 441–444. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, E.W.; Miller, W. Optimal alignments in linear space. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1988, 4, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.J.; Eddy, S.R. Nhmmer: DNA homology search with profile hmms. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2487–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. Vsearch: A versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.H.; Ha, S.M.; Kwon, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.; Chun, J. Introducing ezbiocloud: A taxonomically united database of 16s rrna gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. Uchime improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, A.; Lee, S.-M. Estimating the number of classes via sample coverage. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1992, 87, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A. Estimating the population size for capture-recapture data with unequal catchability. Biometrics 1987, 43, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Overton, W.S. Robust estimation of population size when capture probabilities vary among animals. Ecology 1979, 60, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, A.; Shen, T.-J. Nonparametric estimation of shannon’s index of diversity when there are unseen species in sample. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2003, 10, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faith, D.P. Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol. Conserv. 1992, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Divergence measures based on the shannon entropy. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1991, 37, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beals, E.W. Bray-curtis ordination: An effective strategy for analysis of multivariate ecological data. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1984, 14, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Bittinger, K.; Charlson, E.S.; Hoffmann, C.; Lewis, J.; Wu, G.D.; Collman, R.G.; Bushman, F.D.; Li, H. Associating microbiome composition with environmental covariates using generalized unifrac distances. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2106–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamady, M.; Lozupone, C.; Knight, R. Fast unifrac: Facilitating high-throughput phylogenetic analyses of microbial communities including analysis of pyrosequencing and phylochip data. ISME J. 2010, 4, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Doak, T.G. A parsimony approach to biological pathway reconstruction/inference for genomes and metagenomes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2009, 5, e1000465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langille, M.G.; Zaneveld, J.; Caporaso, J.G.; McDonald, D.; Knights, D.; Reyes, J.A.; Clemente, J.C.; Burkepile, D.E.; Thurber, R.L.V.; Knight, R. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16s rrna marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, C.; Kujawski, M.; Chu, H.; Li, L.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Cantin, E.M. Bacteroides fragilis polysaccharide a induces il-10 secreting b and t cells that prevent viral encephalitis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Wang, D.; Long, J.; Yang, X.; Lin, J.; Song, Y.; Xie, F.; Xun, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Gut microbiome is associated with the clinical response to anti-pd-1 based immunotherapy in hepatobiliary cancers. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e003334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, P.; van Baarle, L.; Gianluca, M.; Kristin, V. How microbial food fermentation supports a tolerant gut. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, 2000036. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen, E.B.; Emanuel, E.C.; Stephan, T.; Frost, G.; Albert, K.G.; Albert, K.G.; Gilles, M.; Arjen, N.; Karen, P.S.; Stahl, B.; et al. Short chain fatty acids in human gut and metabolic health. Benef. Microbes 2020, 11, 411–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piero, P.; Leonilde, B.; Mirco, V.; Maria De, A.; Ilaria, F.; Elisa, L.; Mohamad, K.; David, Q.H.W.; Markus, S.; Agostino Di, C. Gut microbiota and short chain fatty acids: Implications in glucose homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, L.; Ting, W.; Jingzhi, W.; Yi, T.; Zhongbin, D. Commensal bacterial glycosylation at the interface of host-bacteria interactions. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2545421. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.; Li, J.; Ying, S. Tryptophan metabolism and gut microbiota: A novel regulatory axis integrating the microbiome, immunity, and cancer. Metabolites 2023, 13, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar, J.S.; Ota, N.; Pokorzynski, N.D.; Peng, Y.; Jaochico, A.; Sangaraju, D.; Skippington, E.; Lekkerkerker, A.N.; Rothenberg, M.E.; Tan, M.-W.; et al. Il-22 alters gut microbiota composition and function to increase aryl hydrocarbon receptor activity in mice and humans. Microbiome 2023, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyan, L.; Max, N.; Willem, M.d.V.; Elena, R. Microbial tryptophan metabolism tunes host immunity, metabolism, and extraintestinal disorders. Metabolites 2022, 12, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, R. Gut microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolites maintain gut and systemic homeostasis. Cells 2022, 11, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, N.; Ge, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ren, F.; Wu, Z. Tryptophan and the innate intestinal immunity: Crosstalk between metabolites, host innate immune cells, and microbiota. Eur. J. Immunol. 2022, 52, 856–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, N.; Su, X.; Gao, Y.; Yang, R. Gut-microbiota-derived metabolites maintain gut and systemic immune homeostasis. Cells 2023, 12, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su-Kil, S.; Byungsuk, K. Immune regulation through tryptophan metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claus, S.P.; Guillou, H.; Ellero-Simatos, S. The gut microbiota: A major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2016, 2, 16003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimer, J.M.; Karlsson, K.H.; Lövgren-Bengtsson, K.; Magnusson, S.E.; Fuentes, A.; Stertman, L. Matrix-m™ adjuvant induces local recruitment, activation and maturation of central immune cells in absence of antigen. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | B1 (n = 35) | B2 (n = 35) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65 ± 4.2 | ||

| Female sex (%) | 23 (65.7) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 2.5 | ||

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S IgG (U/mL) | 12,146.1 ± 11,573.2 | 15,156.5 ± 13,015.8 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory test results | |||

| WBC (103/µL) | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 0.180 |

| ANC (/µL) | 2966.8 ± 846.0 | 2900.5 ± 862.3 | 0.878 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.6 ± 1.1 | 13.4 ± 1.1 | 0.217 |

| MCV (fL) | 93.9 ± 3.2 | 93.7 ± 3.3 | 0.787 |

| MCH (pg) | 32.2 ± 1.4 | 32.0 ± 1.3 | 0.029 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 34.3 ± 0.8 | 34.2 ± 0.6 | 0.198 |

| Platelet count (103/µL) | 245.1 ± 86.1 | 239.7 ± 82.4 | 0.112 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 15.5 ± 3.3 | 18.0 ± 4.3 | 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.471 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 0.007 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 190.6 ± 43.5 | 190.6 ± 49.3 | 0.675 |

| AST (IU/L) | 26.3 ± 6.2 | 27.6 ± 6.0 | 0.110 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 20.9 ± 5.4 | 22.9 ± 10.3 | 0.234 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 28.7 ± 35.4 | 30.0 ± 36.6 | 0.462 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.497 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.533 |

| Underlying diseases | |||

| Hypertension | 5 (14.3) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (14.3) |

| Increased | |||||

| Taxon Name | Taxon Rank | B1 | B2 | LDA Effect Size | p value |

| Verrucomicrobiae | Class | 0.05867 | 0.48008 | 3.35640 | 0.03572 |

| Coriobacteriia | Class | 0.30181 | 0.33425 | 2.91045 | 0.04755 |

| Verrucomicrobiales | Order | 0.05867 | 0.48008 | 3.32644 | 0.03572 |

| Coriobacteriales | Order | 0.30181 | 0.33425 | 2.91045 | 0.04755 |

| Akkermansiaceae | Family | 0.05867 | 0.48008 | 3.34064 | 0.03572 |

| Coriobacteriaceae | Family | 0.30181 | 0.33425 | 2.91045 | 0.04755 |

| Akkermansia | Genus | 0.05867 | 0.48008 | 3.34346 | 0.03572 |

| Collinsella | Genus | 0.07894 | 0.21245 | 2.75135 | 0.04464 |

| Anaerotruncus | Genus | 0.00388 | 0.02863 | 2.23196 | 0.01588 |

| Bacteroides fragilis | Species | 1.36713 | 2.93033 | 4.03647 | 0.02999 |

| Fusobacterium necrogenes | Species | 0.71276 | 1.39400 | 3.89480 | 0.02290 |

| Akkermansia muciniphila | Species | 0.05867 | 0.46066 | 3.31958 | 0.04992 |

| Ruminococcaceae PAC000661_g PAC001052_s | Species | 0.11072 | 0.19429 | 2.84822 | 0.02400 |

| Collinsella aerofaciens | Species | 0.07894 | 0.21245 | 2.75135 | 0.04464 |

| Oscillibacter KI271778_s | Species | 0.04889 | 0.14275 | 2.70632 | 0.04564 |

| Decreased | |||||

| Taxon name | Taxon Rank | B1 | B2 | LDA Effect Size | p value |

| Bacteroidetes | Phylum | 50.18577 | 41.78608 | 4.63612 | 0.01297 |

| Bacteroidia | Class | 50.18534 | 41.78566 | 4.63612 | 0.01297 |

| Bacteroidales | Order | 50.18534 | 41.78566 | 4.63612 | 0.01297 |

| Lachnospiraceae_uc | Genus | 0.02531 | 0.01802 | 2.02576 | 0.00082 |

| Prevotella bivia | Species | 1.87355 | 0.28048 | 4.00505 | 0.03145 |

| Increased | ||||

| Taxon | B1 Average | B2 Average | t value | p value |

| Bacteria; Bacteroidetes; Bacteroidia; Bacteroidales; Bacteroidaceae; Bacteroides; Bacteroides fragilis | 524.44118 | 933.64706 | −2.09804 | 0.04364 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Lachnospiraceae; Blautia; Blautia glucerasea | 0.00000 | 0.14706 | −2.38530 | 0.02296 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Christensenellaceae; PAC001360_g; FJ367045_s | 0.97059 | 3.44118 | −2.30547 | 0.02757 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Ruminococcaceae; Pseudoflavonifractor; Flavonifractor plautii | 43.23529 | 114.41176 | −2.48175 | 0.01834 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Ruminococcaceae; Oscillibacter; KI271778_s | 18.47059 | 43.91176 | −2.17134 | 0.03720 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Bacilli; Lactobacillales; Lactobacillaceae; Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus intestinalis | 0.00000 | 0.11765 | −2.09762 | 0.04368 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Bacilli; Lactobacillales; Lactobacillaceae; Lactobacillus; Lactobacillus murinus | 0.00000 | 0.11765 | −2.09762 | 0.04368 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Ruminococcaceae; PAC001637_g; PAC001637_s | 4.23529 | 8.08824 | −2.17707 | 0.03673 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Lachnospiraceae; PAC002152_g; PAC002152_s | 0.02941 | 0.20588 | −2.24364 | 0.03169 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Bacilli; Lactobacillales; Streptococcaceae; Streptococcus; Streptococcus salivarius | 22.20588 | 42.94118 | −2.21749 | 0.03359 |

| Decreased | ||||

| Taxon | B1 Average | B2 Average | t value | p value |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Tissierellia; Tissierellales; Peptoniphilaceae; Anaerococcus; Anaerococcus lactolyticus | 0.58824 | 0.08824 | 2.15322 | 0.03870 |

| Bacteria; Actinobacteria; Coriobacteriia; Coriobacteriales; Coriobacteriaceae; Gordonibacter; Gordonibacter pamelaeae | 0.11765 | 0.00000 | 2.09762 | 0.04368 |

| Bacteria; Proteobacteria; Betaproteobacteria; Burkholderiales; Oxalobacteraceae; Oxalobacter; KI392030_s | 1.67647 | 0.41176 | 2.10603 | 0.04289 |

| Bacteria; Fusobacteria; Fusobacteria_c; Fusobacteriales; Leptotrichiaceae; Sneathia; Leptotrichia amnionii | 2.44118 | 0.67647 | 2.11907 | 0.04170 |

| Bacteria; Firmicutes; Clostridia; Clostridiales; Lachnospiraceae; Marvinbryantia; PAC002376_s | 1.94118 | 0.82353 | 2.08135 | 0.04524 |

| Bacteria; Bacteroidetes; Bacteroidia; Bacteroidales; Porphyromonadaceae; Parabacteroides; Parabacteroides_uc | 24.64706 | 12.79412 | 2.12536 | 0.04113 |

| Increased | |||

| Ortholog | Definition | LDA Effect Size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Module (PICRUSt) | Definition | LDA Effect Size | p value |

| M00207 | Putative multiple sugar transport system | 2.57795109 | 0.026388634 |

| M00038 | Tryptophan metabolism, tryptophan => kynurenine => 2-aminomuconate | 2.539665479 | 0.047659036 |

| Module (MinPath) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Pathway (PICRUSt) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Pathway (MinPath) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Decreased | |||

| Ortholog | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Module (PICRUSt) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| M00126 | Tetrahydrofolate biosynthesis, GTP ≥ THF | 2.60949489 | 0.022580649 |

| Module (MinPath) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Pathway (PICRUSt) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| ko01100 | Metabolic pathways | 3.204292376 | 0.033634627 |

| Pathway (MinPath) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| ko04210 | Apoptosis | 2.855686688 | 0.005164992 |

| ko04974 | Protein digestion and absorption | 2.748775013 | 0.040129783 |

| Characteristics | Low Responders (n = 27) | High Responders (n = 8) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.1 ± 4.0 | 64.5 ± 4.8 | 0.527 |

| Female sex (%) | 8 (29.6) | 4 (50.0) | 0.402 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.8 ± 2.7 | 23.4 ± 1.8 | 0.582 |

| Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S IgG (U/mL) | 15,213.8 ± 11,500.9 | 1792.5 ± 679.5 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory test results | |||

| WBC (103/µL) | 5.6 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 0.783 |

| ANC (/µL) | 2961.4 ± 775.0 | 2985.2 ± 1116.0 | 0.773 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.5 ± 1.0 | 13.8 ± 1.4 | 0.651 |

| MCV (fL) | 93.1 ± 3.0 | 96.6 ± 2.4 | 0.006 |

| MCH (pg) | 31.8 ± 1.2 | 33.5 ± 1.5 | 0.015 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 34.2 ± 0.6 | 34.7 ± 1.1 | 0.145 |

| Platelet count (103/uL) | 244.8 ± 92.8 | 246.1 ± 63.5 | 0.922 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 15.0 ± 3.4 | 17.2 ± 2.4 | 0.065 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.568 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | 0.281 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 195.3 ± 45.1 | 174.8 ± 35.5 | 0.179 |

| AST (IU/L) | 25.4 ± 3.3 | 29.2 ± 11.5 | 0.363 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 20.8 ± 5.4 | 21.2 ± 5.7 | 0.768 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 22.5 ± 12.8 | 49.8 ± 69.4 | 0.129 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | >0.999 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.316 |

| Underlying diseases | |||

| Hypertension | 3 (11.1) | 2 (25.0) | 0.568 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (14.8) | 1 (12.5) | >0.999 |

| Dyslipidemia | |||

| HBV carrier |

| Low Responders > High Responders | |||||

| Taxon Name | Taxon Rank | Low Responders | High Responders | LDA Effect Size | p value |

| Mogibacterium_f | Family | 0.13663 | 0.03862 | 2.68501 | 0.01903 |

| Alloprevotella | Genus | 1.34650 | 0.00423 | 3.88420 | 0.00919 |

| Agathobacter | Genus | 1.22359 | 0.10317 | 3.68815 | 0.01125 |

| Paraprevotella | Genus | 0.27037 | 0.00053 | 3.10451 | 0.00408 |

| Agathobacter rectalis | Species | 1.22112 | 0.10317 | 3.68731 | 0.01125 |

| Oscillibacter PAC001129_s | Species | 0.60892 | 0.04868 | 3.43149 | 0.01566 |

| Paraprevotella clara | Species | 0.25281 | 0.00053 | 3.07496 | 0.00660 |

| PAC001052_s | Species | 0.14143 | 0.00000 | 2.85678 | 0.04837 |

| Oscillibacter_uc | Species | 0.10069 | 0.03545 | 2.58717 | 0.04359 |

| Low Responders < High Responders | |||||

| Taxon name | Taxon rank | Low Responders | High Responders | LDA effect size | p value |

| Pasteurellales | Order | 0.13045 | 0.21111 | 2.76005 | 0.01753 |

| Pasteurellaceae | Family | 0.13045 | 0.21111 | 2.75910 | 0.01753 |

| Ruminococcus_g5 | Genus | 0.28285 | 0.39735 | 3.21498 | 0.02741 |

| Haemophilus | Genus | 0.13045 | 0.20847 | 2.75605 | 0.01753 |

| Romboutsia | Genus | 0.05624 | 0.13862 | 2.65415 | 0.02366 |

| Agathobaculum | Genus | 0.12757 | 0.22116 | 2.63919 | 0.04995 |

| Faecalimonas | Genus | 0.00027 | 0.09841 | 2.62938 | 0.01406 |

| Ruminococcus gnavus | Species | 0.28285 | 0.39735 | 3.21498 | 0.02741 |

| Bacteroides PAC002300_s | Species | 0.00014 | 0.33016 | 3.17412 | 0.03772 |

| Bacteroides PAC002364_s | Species | 0.00069 | 0.30053 | 3.12731 | 0.00062 |

| Alistipes finegoldii | Species | 0.01084 | 0.18783 | 3.00748 | 0.01906 |

| Faecalimonas umbilicata | Species | 0.00027 | 0.09841 | 2.61101 | 0.01406 |

| Agathobaculum butyriciproducens | Species | 0.10082 | 0.17460 | 2.56622 | 0.04077 |

| Clostridium_g24 PAC001295_s | Species | 0.03429 | 0.10635 | 2.55174 | 0.01099 |

| Low Responders > High Responders | |||

| Ortholog | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Module (PICRUSt) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Module (MinPath) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| M00389 | APC/C complex | 2.54234332 | 0.01271625 |

| Pathway (PICRUSt) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Pathway (MinPath) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Low Responders < High Responders | |||

| Ortholog | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Module (PICRUSt) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Module (MinPath) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Pathway (PICRUSt) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| - | - | - | - |

| Pathway (MinPath) | Definition | LDA effect size | p value |

| ko05014 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | 2.756572204 | 0.020273273 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seong, H.; Yoon, J.G.; Nham, E.; Choi, Y.J.; Noh, J.Y.; Cheong, H.J.; Kim, W.J.; Lim, S.; Song, J.Y. Vaccine Platform-Dependent Differential Impact on Microbiome Diversity: Potential Advantages of Protein Subunit Vaccines. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121248

Seong H, Yoon JG, Nham E, Choi YJ, Noh JY, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ, Lim S, Song JY. Vaccine Platform-Dependent Differential Impact on Microbiome Diversity: Potential Advantages of Protein Subunit Vaccines. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121248

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeong, Hye, Jin Gu Yoon, Eliel Nham, Yu Jung Choi, Ji Yun Noh, Hee Jin Cheong, Woo Joo Kim, Sooyeon Lim, and Joon Young Song. 2025. "Vaccine Platform-Dependent Differential Impact on Microbiome Diversity: Potential Advantages of Protein Subunit Vaccines" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121248

APA StyleSeong, H., Yoon, J. G., Nham, E., Choi, Y. J., Noh, J. Y., Cheong, H. J., Kim, W. J., Lim, S., & Song, J. Y. (2025). Vaccine Platform-Dependent Differential Impact on Microbiome Diversity: Potential Advantages of Protein Subunit Vaccines. Vaccines, 13(12), 1248. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121248