Immunogenicity of HIV-1 Env-Gag VLP mRNA and Adenovirus Vector Vaccines in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. HIV-1 Env-Gag VLP mRNA and Adenovirus Vector Vaccines

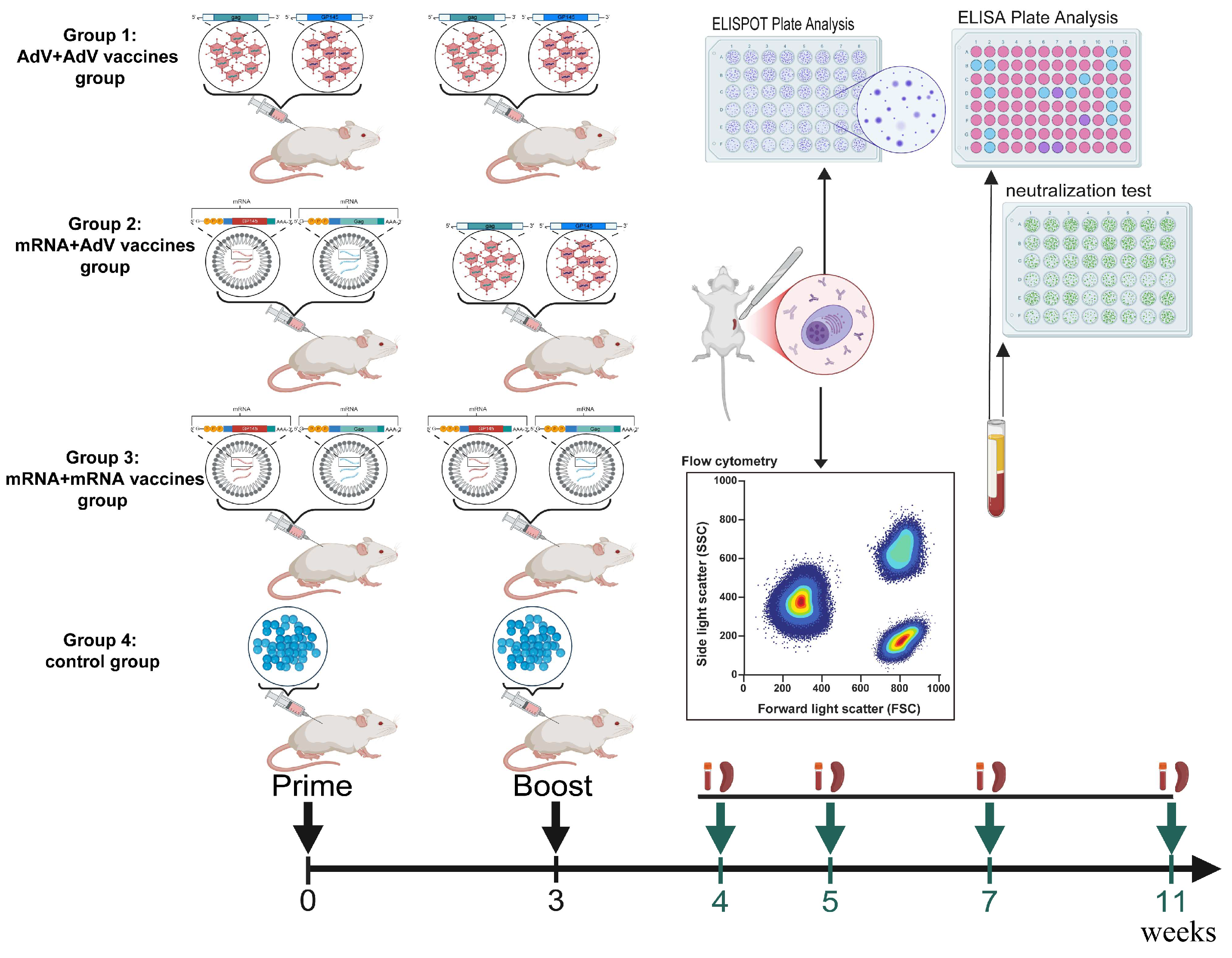

2.2. Mouse Immunization and Detection Protocols

2.3. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.4. Pseudovirus-Based Neutralization Assay

2.5. Enzyme Linked Immunospot (ELISPOT) Assay

2.6. Intracellular Cytokine Staining (ICS) by Flow Cytometry

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

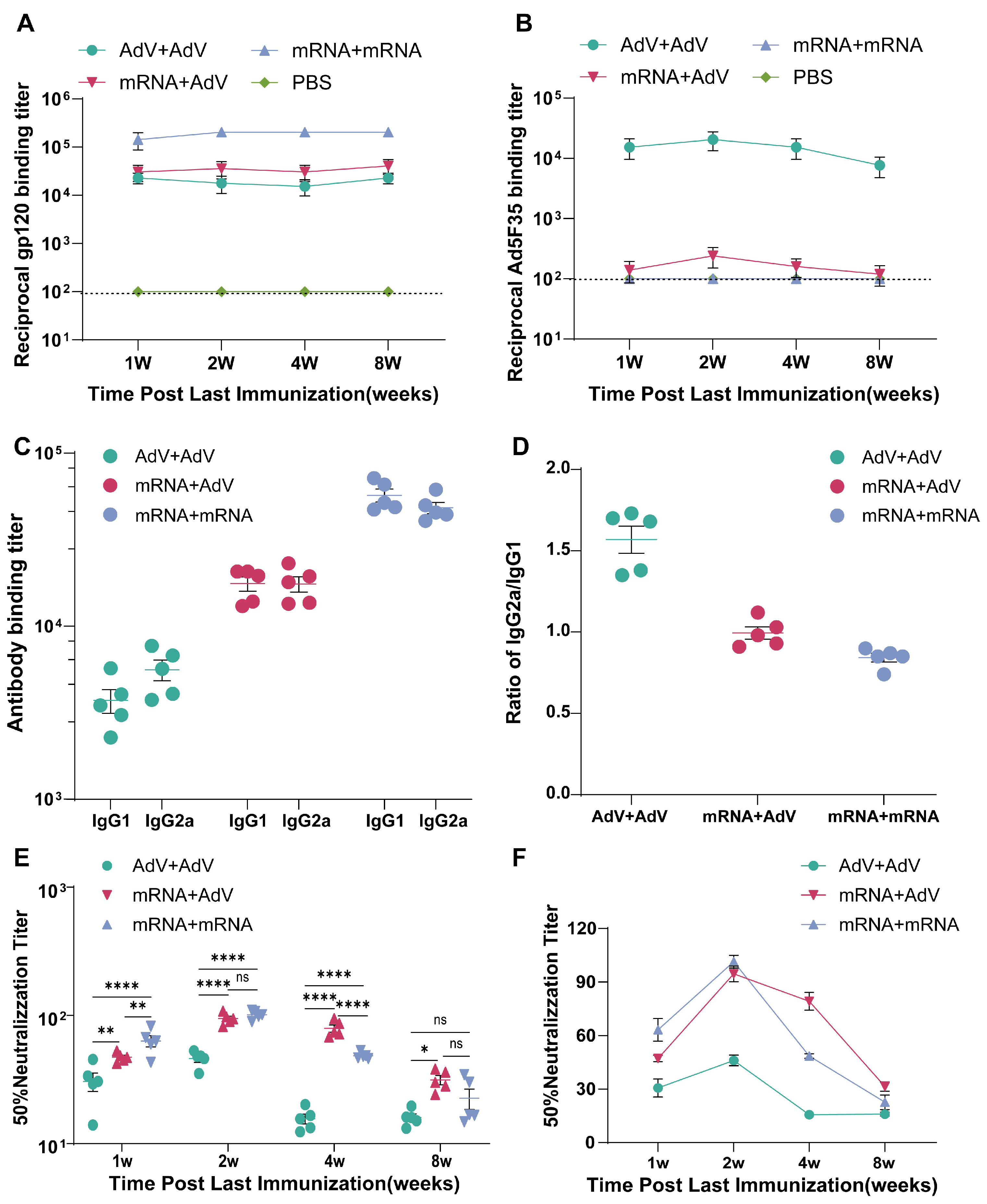

3.1. Immune Response Types Triggered by Homologous and Heterologous Immunization with mRNA and Adenovirus Vector Vaccine

3.2. The Levels of Adenovirus Ad5F35-Binding Antibodies in Mice Following Vaccination

3.3. Detection of HIV-1 Subtype AE-Specific Neutralizing Antibodies in Immunized Mouse Serum

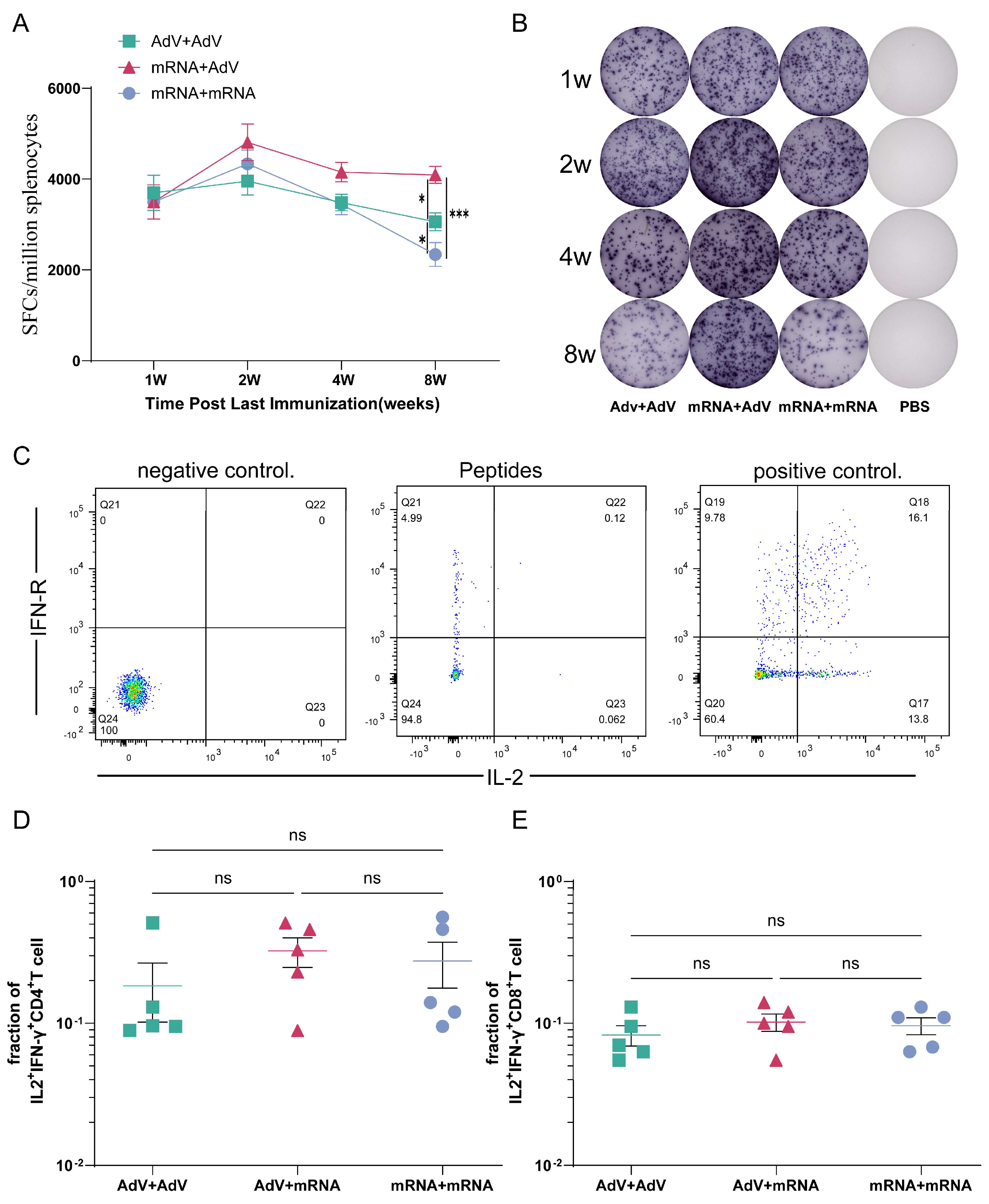

3.4. Detection of Cellular Immune Responses in Mice After Immunization

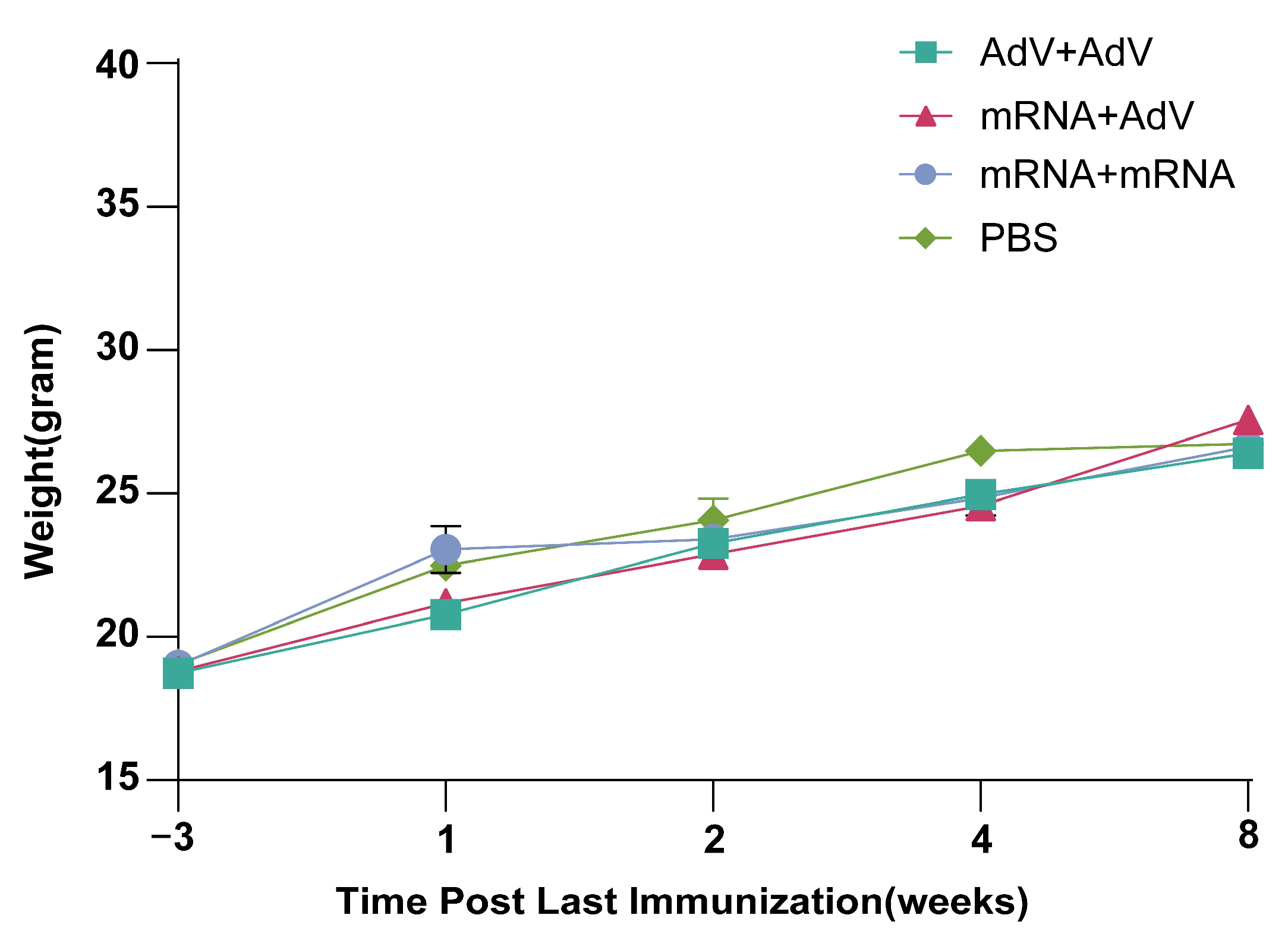

3.5. Safety Testing of Mice After Vaccine Immunization

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kardani, K.; Bolhassani, A.; Shahbazi, S. Prime-boost vaccine strategy against viral infections: Mechanisms and benefits. Vaccine 2016, 34, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, L.; Maue, A.C. Effects of aging on T cell function. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009, 21, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bot, A.; Qiu, Z.; Wong, R.; Obrocea, M.; Smith, K.A. Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) at the heart of heterologous prime-boost vaccines and regulation of CD8+ T cell immunity. J. Transl. Med. 2010, 8, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, K.M.; Agrawal, N.; Du, S.X.; Muranaka, J.E.; Bauer, K.; Leaman, D.P.; Phung, P.; Limoli, K.; Chen, H.; Boenig, R.I.; et al. Prime-boost immunization of rabbits with HIV-1 gp120 elicits potent neutralization activity against a primary viral isolate. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e52732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Arthos, J.; Lawrence, J.M.; Van Ryk, D.; Mboudjeka, I.; Shen, S.; Chou, T.H.; Montefiori, D.C.; Lu, S. Enhanced immunogenicity of gp120 protein when combined with recombinant DNA priming to generate antibodies that neutralize the JR-FL primary isolate of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 7933–7937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burm, R.; Maravelia, P.; Ahlen, G.; Ciesek, S.; Caro Perez, N.; Pasetto, A.; Urban, S.; Van Houtte, F.; Verhoye, L.; Wedemeyer, H.; et al. Novel prime-boost immune-based therapy inhibiting both hepatitis B and D virus infections. Gut 2023, 72, 1186–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Shaw, R.H.; Stuart, A.S.V.; Greenland, M.; Aley, P.K.; Andrews, N.J.; Cameron, J.C.; Charlton, S.; Clutterbuck, E.A.; Collins, A.M.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of heterologous versus homologous prime-boost schedules with an adenoviral vectored and mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Com-COV): A single-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2021, 398, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excler, J.L.; Kim, J.H. Novel prime-boost vaccine strategies against HIV-1. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2019, 18, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleshin, S.E.; Timofeev, A.V.; Khoretonenko, M.V.; Zakharova, L.G.; Pashvykina, G.V.; Stephenson, J.R.; Shneider, A.M.; Altstein, A.D. Combined prime-boost vaccination against tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) using a recombinant vaccinia virus and a bacterial plasmid both expressing TBE virus non-structural NS1 protein. BMC Microbiol. 2005, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priddy, F.H.; Brown, D.; Kublin, J.; Monahan, K.; Wright, D.P.; Lalezari, J.; Santiago, S.; Marmor, M.; Lally, M.; Novak, R.M.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a replication-incompetent adenovirus type 5 HIV-1 clade B gag/pol/nef vaccine in healthy adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 1769–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catanzaro, A.T.; Koup, R.A.; Roederer, M.; Bailer, R.T.; Enama, M.E.; Moodie, Z.; Gu, L.; Martin, J.E.; Novik, L.; Chakrabarti, B.K.; et al. Phase 1 safety and immunogenicity evaluation of a multiclade HIV-1 candidate vaccine delivered by a replication-defective recombinant adenovirus vector. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 194, 1638–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, R.M.; Kim, J.H.; Robb, M.L.; Michael, N.L. Prime-boost immunization with poxvirus or adenovirus vectors as a strategy to develop a protective vaccine for HIV-1. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2010, 9, 1055–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooraei, S.; Bahrulolum, H.; Hoseini, Z.S.; Katalani, C.; Hajizade, A.; Easton, A.J.; Ahmadian, G. Virus-like particles: Preparation, immunogenicity and their roles as nanovaccines and drug nanocarriers. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, H.; Batool, S.; Asif, S.; Ali, M.; Abbasi, B.H. Virus-Like Particles: Revolutionary Platforms for Developing Vaccines Against Emerging Infectious Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 790121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheirvari, M.; Liu, H.; Tumban, E. Virus-like Particle Vaccines and Platforms for Vaccine Development. Viruses 2023, 15, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Wang, Y.; Du, J. Human Papillomavirus Vaccines: An Updated Review. Vaccines 2020, 8, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzzi, F.; Semprini, M.S.; Scalambra, L.; Palladini, A.; Angelicola, S.; Cappello, C.; Pittino, O.M.; Nanni, P.; Lollini, P.L. Virus-like Particle (VLP) Vaccines for Cancer Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengarten, J.F.; Schatz, S.; Wolf, T.; Barbe, S.; Stitz, J. Components of a HIV-1 vaccine mediate virus-like particle (VLP)-formation and display of envelope proteins exposing broadly neutralizing epitopes. Virology 2022, 568, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Narayanan, E.; Liu, Q.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Boswell, K.; Ding, S.; Hu, Z.; Follmann, D.; Lin, Y.; Miao, H.; et al. A multiclade env-gag VLP mRNA vaccine elicits tier-2 HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies and reduces the risk of heterologous SHIV infection in macaques. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 2234–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.; Teeuwsen, V.J.; Deml, L.; Notka, F.; Haaksma, A.G.; Jhagjhoorsingh, S.S.; Niphuis, H.; Wolf, H.; Heeney, J.L. Cytotoxic T cells and neutralizing antibodies induced in rhesus monkeys by virus-like particle HIV vaccines in the absence of protection from SHIV infection. Virology 1998, 245, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chackerian, B.; Lowy, D.R.; Schiller, J.T. Induction of autoantibodies to mouse CCR5 with recombinant papillomavirus particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 2373–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabel, F.; Kündig, T.M.; Bachmann, M.F. Virus-induced humoral immunity: On how B cell responses are initiated. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2013, 3, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, H.J.; Jegerlehner, A.; Bachmann, M.F. Pattern recognition by B cells: The role of antigen repetitiveness versus Toll-like receptors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 319, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.L.; Klaniecki, J.; Dykers, T.; Sridhar, P.; Travis, B.M. Neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 BRU and SF2 isolates generated in mice immunized with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing HIV-1 (BRU) envelope glycoproteins and boosted with homologous gp160. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 1991, 7, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Hao, Y.; Feng, X. Immunogenicity of HIV-1 Env mRNA and Env-Gag VLP mRNA Vaccines in Mice. Vaccines 2025, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, D.; Ma, Q.; Hao, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Feng, X. Decade-Long Sustained Cellular Immunity Induced by Sequential and Repeated Vaccination with Four Heterologous HIV Vaccines in Rhesus Macaques. Vaccines 2025, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Ma, Q.; Yang, J.; Li, H. Immunogenicity of Multiple Vaccines Expressing HIV-1 AEgp145 Administered Alone or in Combination with gag Vaccine in Mice. bingduxuebao 2025, 41, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, F.; Atasoy, B.T.; Yalcin, S.; Bitirim, V.C. Membrane-targeted immunogenic compositions using exosome mimetic approach for vaccine development against SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riou, C.; Bhiman, J.N.; Ganga, Y.; Sawry, S.; Ayres, F.; Baguma, R.; Balla, S.R.; Benede, N.; Bernstein, M.; Besethi, A.S.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of booster vaccination and fractional dosing with Ad26.COV2.S or BNT162b2 in Ad26.COV2.S-vaccinated participants. medRxiv 2023, 4, e0002703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Mateus, J.; Coelho, C.H.; Dan, J.M.; Moderbacher, C.R.; Gálvez, R.I.; Cortes, F.H.; Grifoni, A.; Tarke, A.; Chang, J.; et al. Humoral and cellular immune memory to four COVID-19 vaccines. Cell 2022, 185, 2434–2451.e2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J. Adenovirus Vectors: Excellent Tools for Vaccine Development. Immune Netw. 2021, 21, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, S.A.; Lorincz, R.; Boucher, P.; Curiel, D.T. Adenoviral vector vaccine platforms in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qureshi, H.; Ma, Z.M.; Huang, Y.; Hodge, G.; Thomas, M.A.; DiPasquale, J.; DeSilva, V.; Fritts, L.; Bett, A.J.; Casimiro, D.R.; et al. Low-dose penile SIVmac251 exposure of rhesus macaques infected with adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) and then immunized with a replication-defective Ad5-based SIV gag/pol/nef vaccine recapitulates the results of the phase IIb step trial of a similar HIV-1 vaccine. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 2239–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, L.; Pan, W.; Zhang, M.; Hong, Z.; Ma, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, L. Epidemiology of adenovirus type 5 neutralizing antibodies in healthy people and AIDS patients in Guangzhou, southern China. Vaccine 2011, 29, 3837–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlandi, C.; Stefanetti, G.; Barocci, S.; Buffi, G.; Diotallevi, A.; Rocchi, E.; Ceccarelli, M.; Peluso, S.; Vandini, D.; Carlotti, E.; et al. Comparing Heterologous and Homologous COVID-19 Vaccination: A Longitudinal Study of Antibody Decay. Viruses 2023, 15, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.H.; Chang, S.Y.; Lin, P.H.; Hsieh, M.J.; Chang, H.H.; Cheng, C.Y.; Yang, H.C.; Pan, C.F.; Ieong, S.M.; Chao, T.L.; et al. Immune response and safety of heterologous ChAdOx1-nCoV-19/mRNA-1273 vaccination compared with homologous ChAdOx1-nCoV-19 or homologous mRNA-1273 vaccination. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2022, 121, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.M.; Sun, S.H.; Hu, Z.L.; Yin, M.; Xiao, C.J.; Zhang, J.C. Improved immunogenicity of a tuberculosis DNA vaccine encoding ESAT6 by DNA priming and protein boosting. Vaccine 2004, 22, 3622–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, J.I.; Bagarazzi, M.; Pachuk, C.; Weiner, D.B. DNA priming-protein boosting enhances both antigen-specific antibody and Th1-type cellular immune responses in a murine herpes simplex virus-2 gD vaccine model. DNA Cell Biol. 1999, 18, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, J.E.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Panchal, R.G.; Bavari, S.; Lyons, C.R.; Lovchik, J.A.; Golding, B.; Shiloach, J.; Lu, S. Passive immunotherapy of Bacillus anthracis pulmonary infection in mice with antisera produced by DNA immunization. Vaccine 2006, 24, 5872–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Sun, S.; Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y. Augmented humoral and cellular immune responses of a hepatitis B DNA vaccine encoding HBsAg by protein boosting. Vaccine 2005, 23, 1649–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Ma, Q.; He, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Hao, Y.; Feng, X. Immunogenicity of HIV-1 Env-Gag VLP mRNA and Adenovirus Vector Vaccines in Mice. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121242

Yang J, Ma Q, He X, Li H, Zhang X, Hao Y, Feng X. Immunogenicity of HIV-1 Env-Gag VLP mRNA and Adenovirus Vector Vaccines in Mice. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121242

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jing, Qi Ma, Xiaozhou He, Hongxia Li, Xiaoguang Zhang, Yanzhe Hao, and Xia Feng. 2025. "Immunogenicity of HIV-1 Env-Gag VLP mRNA and Adenovirus Vector Vaccines in Mice" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121242

APA StyleYang, J., Ma, Q., He, X., Li, H., Zhang, X., Hao, Y., & Feng, X. (2025). Immunogenicity of HIV-1 Env-Gag VLP mRNA and Adenovirus Vector Vaccines in Mice. Vaccines, 13(12), 1242. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121242