Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Immune Regulation and Disease: Therapeutic Promise for Next-Generation Vaccines

Abstract

1. Introduction

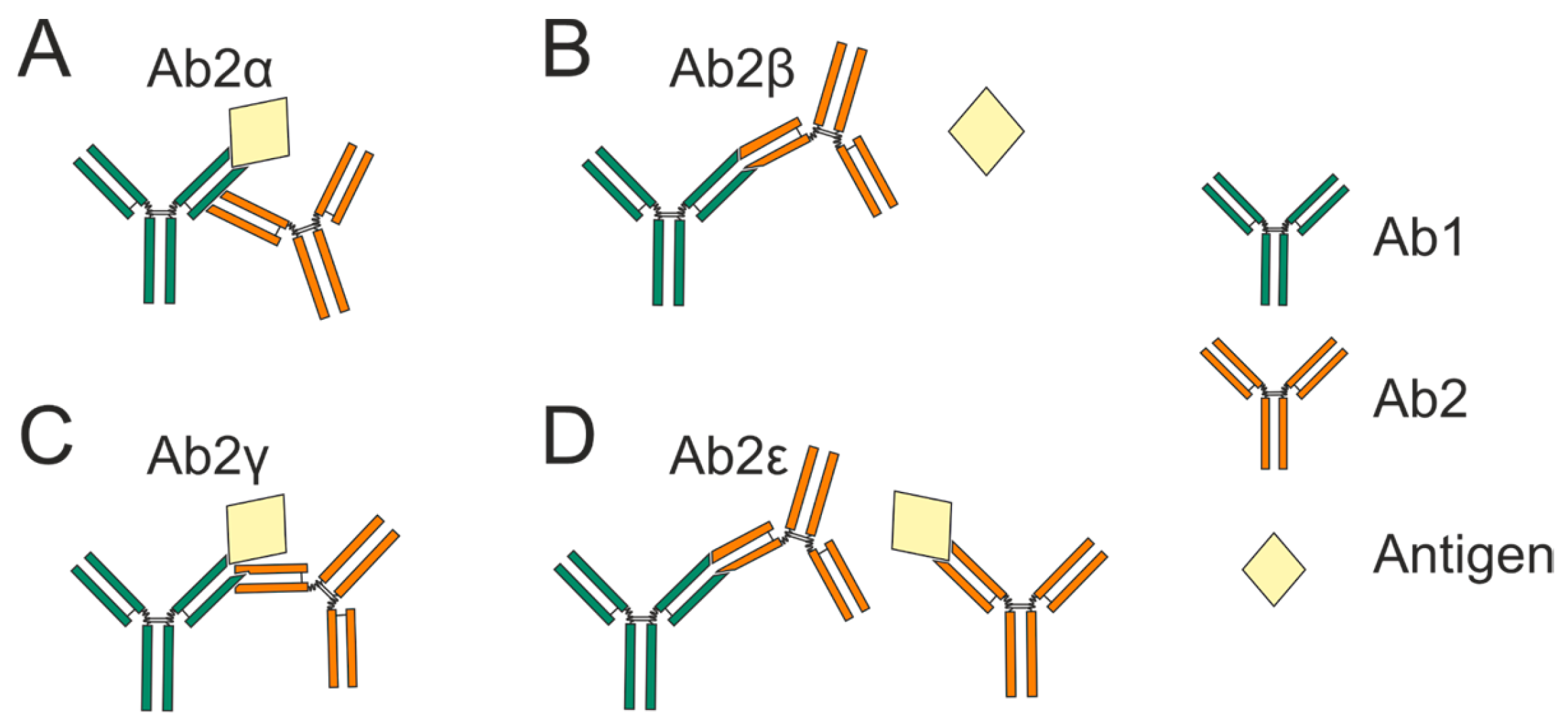

- (a)

- Ab2α binds outside the Ab1 antigen-binding site.

- (b)

- Ab2β antibodies bind specifically to the complementarity-determining region (CDR) of Ab1.This allows them to functionally mimic the antigen and directly compete with it for occupancy of the Ab1 binding site.

- (c)

- (d)

- Ab2ε antibodies demonstrate dual reactivity by recognizing both Ab1 and the cognate antigen itself [4]. Subsequent research has revealed antibodies with expanded polyreactivity that, while similar to Ab2ε, also possess self-binding activity in addition to anti-idiotypic and antigen-binding capabilities [5,6].

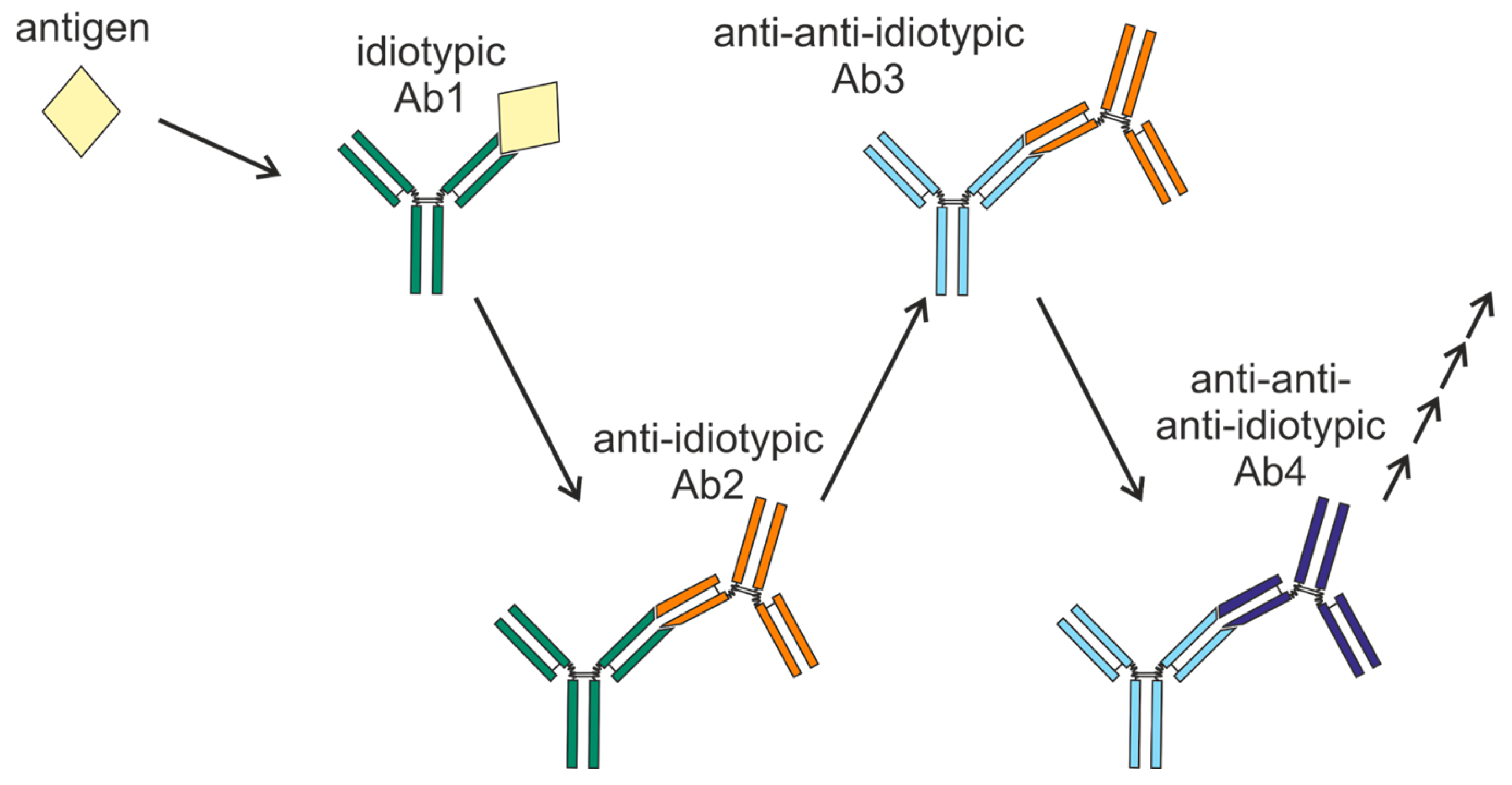

2. Network Concept and Idiotypic Cascades

Similarity in Epitopes Between Antigens and Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies

3. Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Normal and Pathological Conditions

3.1. Autoimmune Diseases: The Balance Between Autoantibodies and Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies

3.2. Therapeutic Applications of Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Autoimmune Diseases

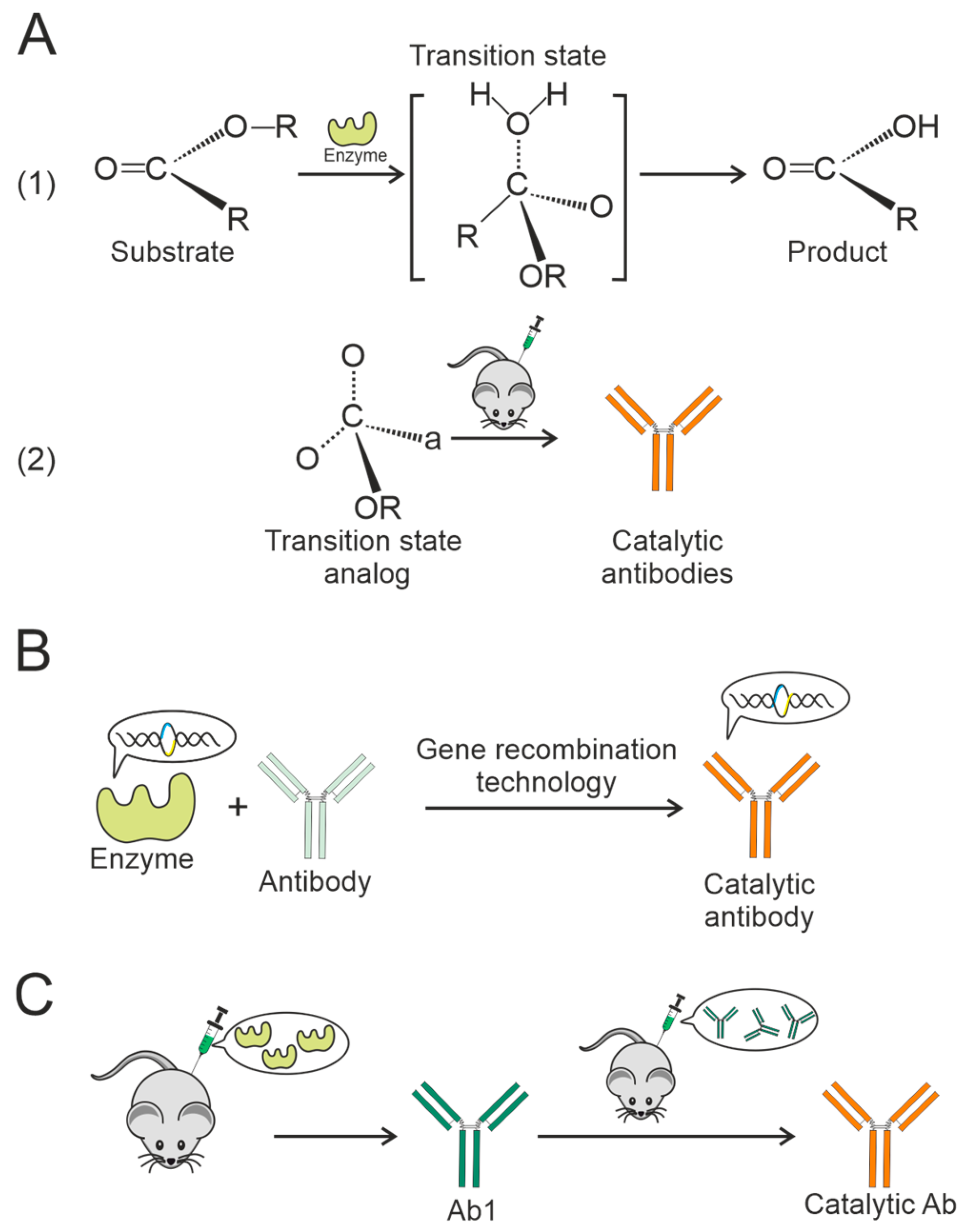

3.3. Formation of Catalytic Antibodies via an Anti-Idiotypic Mechanism

3.4. Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in COVID-19

4. Antibodies with Anti-Drug Activity

Techniques for Detecting Anti-Drug Antibodies

5. Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies That Can Mimic Diverse Molecules

6. Therapeutic Potential of Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Vaccine Development

6.1. Antidiotypic Vaccines Targeting Tumor-Associated Carbohydrate Antigens

6.2. Anti-Idiotypic Vaccines Designed to Target Tumor-Associated Protein Antigens

6.3. Anti-Idiotypic HIV-1 Vaccines

6.4. Anti-Idiotypic Antibody-Based Vaccines: Prospects and Challenges

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ab | Antibody |

| ADAs | Anti-drug antibodies |

| anti-Id Abs | Anti-idiotypic antibodies |

| CD4bs | CD4 binding site |

| CDR | Complementarity-determining region |

| dsDNA | Double-stranded DNA |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EMA (EMA) | European Medicines Agency |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GAD65 | 65-kDa isoform of glutamate decarboxylase |

| HMGF | Human milk fat globule protein |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| NOD | Non-obese diabetic |

| RBD | Receptor-binding domain |

| S | Spike |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| VH | Variable domain |

References

- Cazenave, P.A. Idiotypic-Anti-Idiotypic Regulation of Antibody Synthesis in Rabbits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5122–5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, N.; Oiwa, H.; Kubota, K.; Sakoda, S.; Goto, J. Monoclonal Antibodies Generated against an Affinity-Labeled Immune Complex of an Anti-Bile Acid Metabolite Antibody: An Approach to Noncompetitive Hapten Immunoassays Based on Anti-Idiotype or Anti-Metatype Antibodies. J. Immunol. Methods 2000, 245, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerne, N.K.; Roland, J.; Cazenave, P.A. Recurrent Idiotopes and Internal Images. EMBO J. 1982, 1, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, C.A.; Finley, S.; Waters, S.; Kunkel, H.G. Anti-Immunoglobulin Antibodies. III. Properties of Sequential Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies to Heterologous Anti-Gamma Globulins. Detection of Reactivity of Anti-Idiotype Antibodies with Epitopes of Fc Fragments (Homobodies) and with Epitopes and Idiotopes (Epibodies). J. Exp. Med. 1982, 156, 986–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.-Y.; Brunck, T.K.; Kieber-Emmons, T.; Blalock, J.E.; Kohler, H. Inhibition of Self-Binding Antibodies (Autobodies) by a VH-Derived Peptide. Science 1988, 240, 1034–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.Y.; Kohler, H. Immunoglobulin with Complementary Paratope and Idiotope. J. Exp. Med. 1986, 163, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, H.E.; Jönsson, I.; Lernmark, Å.; Ivarsson, S.; Radtke, J.R.; Hampe, C.S. Decline in Titers of Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies Specific to Autoantibodies to GAD65 (GAD65Ab) Precedes Development of GAD65Ab and Type 1 Diabetes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerne, N.K. Towards a Network Theory of the Immune System. Ann. Immunol. 1974, 125C, 373–389. [Google Scholar]

- Langman, R.; Cohn, M. The ‘Complete’ Idiotype Network Is an Absurd Immune System. Immunol. Today 1986, 7, 100–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.S. Mechanisms of Idiotype Suppression: Role of Anti-Idiotype Antibody. Surv. Immunol. Res. 1982, 1, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodkey, L.S. Autoregulation of Immune Responses via Idiotype Network Interactions. Microbiol. Rev. 1980, 44, 631–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzych, J.M.; Capron, M.; Lambert, P.H.; Dissous, C.; Torres, S.; Capron, A. An Anti-Idiotype Vaccine against Experimental Schistosomiasis. Nature 1985, 316, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlyn, D.; Somasundaram, R.; Zaloudik, J.; Jacob, L.; Harris, D.; Kieny, M.-P.; Sears, H.; Mastrangelo, M. Anti-Idotype and Recombinant Antigen in Immunotherapy of Colorectal Cancer. Cell Biophys. 1994, 24–25, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, R.C.; Adler-Storthz, K.; Henkel, R.D.; Sanchez, Y.; Melnick, J.L.; Dreesman, G.R. Immune Response to Hepatitis B Surface Antigen: Enhancement by Prior Injection of Antibodies to the Idiotype. Science 1983, 221, 853–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.C.; Dreesman, G.R. Enhancement of the Immune Response to Hepatitis B Surface Antigen. In Vivo Administration of Antiidiotype Induces Anti-HBs That Expresses a Similar Idiotype. J. Exp. Med. 1984, 159, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seledtsov, V.I.; Seledtsova, G.V. A Possible Role for Idiotype/Anti-Idiotype B–T Cell Interactions in Maintaining Immune Memory. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geha, R.S. Idiotypic-Antiidiotypic Interactions in Man. Ric. Clin. Lab. 1985, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbain, J.; Wikler, M.; Franssen, J.D.; Collignon, C. Idiotypic Regulation of the Immune System by the Induction of Antibodies against Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1977, 74, 5126–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bona, C.A.; Heber-Katz, E.; Paul, W.E. Idiotype-Anti-Idiotype Regulation. I. Immunization with a Levan-Binding Myeloma Protein Leads to the Appearance of Auto-Anti-(Anti-Idiotype) Antibodies and to the Activation of Silent Clones. J. Exp. Med. 1981, 153, 951–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, H. Immune Response Regulation by Antigen Receptors’ Clone-Specific Nonself Parts. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonelli, L.; Beninati, C.; Teti, G.; Felici, F.; Ciociola, T.; Giovati, L.; Sperindè, M.; Passo, C.L.; Pernice, I.; Domina, M.; et al. Yeast Killer Toxin-Like Candidacidal Ab6 Antibodies Elicited through the Manipulation of the Idiotypic Cascade. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, G.A.; Boulot, G.; Riottot, M.M.; Poljak, R.J. Three-Dimensional Structure of an Idiotope–Anti-Idiotope Complex. Nature 1990, 348, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, N.; Day, J.; Wang, X.; Ferrone, S.; McPherson, A. Crystal Structure of an Anti-Anti-Idiotype Shows It to Be Self-Complementary. J. Mol. Biol. 1996, 255, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.V.; Rose, D.R.; To, R.; Young, N.M.; Bundle, D.R. Exploring the Mimicry of Polysaccharide Antigens by Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies. J. Mol. Biol. 1994, 241, 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Hernandez-Guzman, F.G.; Luo, W.; Wang, X.; Ferrone, S.; Ghosh, D. Structural Basis of Antigen Mimicry in a Clinically Relevant Melanoma Antigen System. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 41546–41552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, T.N.; Bentley, G.A.; Boulot, G.; Greene, M.I.; Tello, D.; Dall, W.; Souchon, H.; Schwarz, F.P.; Mariuzza, R.A.; Poljak, R.J. Bound Water Molecules and Conformational Stabilization Help Mediate an Antigen-Antibody Association. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, B.A.; Goldbaum, F.A.; Ysern, X.; Poijak, R.J.; Mariuzza, R.A. Molecular Basis of Antigen Mimicry by an Anti-Idiotope. Nature 1995, 374, 739–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliani, W.; Polonelli, L.; Conti, S.; Salati, A.; Rocca, P.F.; Cusumano, V.; Mancuso, G.; Teti, G. Neonatal Mouse Immunity against Group B Streptococcal Infection by Maternal Vaccination with Recombinant Anti-Idiotypes. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezuglova, A.M.; Konenkova, L.P.; Doronin, B.M.; Buneva, V.N.; Nevinsky, G.A. Affinity and Catalytic Heterogeneity and Metal-Dependence of Polyclonal Myelin Basic Protein-Hydrolyzing IgGs from Sera of Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Mol. Recognit. 2011, 24, 960–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.Y.; Chia, Y.C.; Yee, H.R.; Fang Cheng, A.Y.; Anjum, C.E.; Kenisi, Y.; Chan, M.K.; Wong, M.B. Immunomodulatory Potential of Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies for the Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases. Futur. Sci. OA 2021, 7, FSO648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, N.I.; Wall, H.; Lindsley, H.B.; Halsey, J.F.; Suzuki, T. Network Theory in Autoimmunity. J. Clin. Investig. 1981, 67, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, D.S.; Bradley, R.J.; Urquhart, C.K.; Kearney, J.F. Naturally Occurring Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Myasthenia Gravis Patients. Nature 1983, 301, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, Y.S.; Ghosh, K.; Badakere, S.S.; Pathare, A.V.; Mohanty, D. Role of Antiidiotypic Antibodies on the Clinical Course of Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2003, 142, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routsias, J.G.; Touloupi, E.; Dotsika, E.; Moulia, A.; Tsikaris, V.; Sakarellos, C.; Sakarellos-Daitsiotis, M.; Moutsopoulos, H.M.; Tzioufas, A.G. Unmasking the Anti-La/SSB Response in Sera from Patients with Sjogren’s Syndrome by Specific Blocking of Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies to La/SSB Antigenic Determinants. Mol. Med. 2002, 8, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestris, F.; Bankhurst, A.D.; Searles, R.P.; Williams, R.C. Studies of Anti—F(Ab’) 2 Antibodies and Possible Immunologic Control Mechanisms in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1984, 27, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Sedykh, S.E.; Ermakov, E.A.; Matveev, A.L.; Odegova, E.I.; Sedykh, T.A.; Shcherbakov, D.N.; Merkuleva, I.A.; Volosnikova, E.A.; Nesmeyanova, V.S.; et al. Natural IgG against S-Protein and RBD of SARS-CoV-2 Do Not Bind and Hydrolyze DNA and Are Not Autoimmune. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdou, N.I.; Suenaga, R.; Hatfield, M.; Evans, M.; Hassanein, K.M. Antiidiotypic Antibodies against Anti-DNA Antibodies in Sera of Families of Lupus Patients. J. Clin. Immunol. 1989, 9, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.M.; Isenberg, D.A. Naturally Occurring Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies Reactive with Anti-DNA Antibodies in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Lupus 1998, 7, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouali, M.; Eyquem, A. Expression of Anti-Idiotypic Clones against Auto-Anti-DNA Antibodies in Normal Individuals. Cell. Immunol. 1983, 76, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampe, C.S. Protective Role of Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Autoimmunity—Lessons for Type 1 Diabetes. Autoimmunity 2012, 45, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.J.; Anderson, C.J.; Stafford, H.A. Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies Prevent the Serologic Detection of Antiribosomal P Autoantibodies in Healthy Adults. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 102, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.J.; Neas, B.R.; Pan, Z.; Taylor-Albert, E.; Reichlin, M.; Stafford, H.A. The Presence of Masked Antiribosomal P Autoantibodies in Healthy Children. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Rowley, M.J.; Mackay, I.R. Anti–Idiotypic Antibodies to Anti-Pdc-E2 in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis and Normal Subjects. Hepatology 1999, 29, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oak, S.; Gilliam, L.K.; Landin-Olsson, M.; Törn, C.; Kockum, I.; Pennington, C.R.; Rowley, M.J.; Christie, M.R.; Banga, J.P.; Hampe, C.S. The Lack of Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies, Not the Presence of the Corresponding Autoantibodies to Glutamate Decarboxylase, Defines Type 1 Diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5471–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Klyaus, N.A.; Sedykh, S.E.; Nevinsky, G.A. Antibodies Specific to Rheumatologic and Neurologic Pathologies Found in Patient with Long COVID. Rheumato 2025, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Örtqvist, E.; Brooks-Worrell, B.; Lynch, K.; Radtke, J.; Bekris, L.M.; Kockum, I.; Agardh, C.-D.; Cilio, C.M.; Lethagen, A.L.; Persson, B.; et al. Changes in GAD65Ab-Specific Antiidiotypic Antibody Levels Correlate with Changes in C-Peptide Levels and Progression to Islet Cell Autoimmunity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, E310–E318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoenfeld, Y. Idiotypic Induction of Autoimmunity: A New Aspect of the Idiotypic Network. FASEB J. 1994, 8, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.Y.; Pisoni, C.N.; Khamashta, M.A. Update on Immunotherapy for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus—What’s Hot and What’s Not! Rheumatology 2009, 48, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. Immunosuppressive Therapy in the Treatment of Immune—Mediated Disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 1992, 6, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörner, T.; Egerer, K.; Feist, E.; Burmester, G.R. Rheumatoid Factor Revisited. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2004, 16, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingegnoli, F.; Castelli, R.; Gualtierotti, R. Rheumatoid Factors: Clinical Applications. Dis. Markers 2013, 35, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, T.; Hosono, O.; Koide, J.; Homma, M.; Abe, T. Suppression of Rheumatoid Factor Synthesis by Antiidiotypic Antibody in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients with Cross—Reactive Idiotypes. Arthritis Rheum. 1985, 28, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, T.R.; Bogdani, M.; LeBoeuf, R.C.; Kirk, E.A.; Maziarz, M.; Banga, J.P.; Oak, S.; Pennington, C.A.; Hampe, C.S. Modulation of Diabetes in NOD Mice by GAD65—Specific Monoclonal Antibodies Is Epitope Specific and Accompanied by Anti—Idiotypic Antibodies. Immunology 2008, 123, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, F. Catalytic Antibodies as Designer Proteases and Esterases. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4885–4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H. Recent Advances in Abzyme Studies 1. J. Biochem. 1994, 115, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Shayakhmetova, L.S.; Nikitin, A.O.; Sedykh, T.A.; Matveev, A.L.; Shanshin, D.V.; Volosnikova, E.A.; Merkuleva, I.A.; Shcherbakov, D.N.; Tikunova, N.V.; et al. Natural Antibodies Produced in Vaccinated Patients and COVID-19 Convalescents Hydrolyze Recombinant RBD and Nucleocapsid (N) Proteins. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Sedykh, S.E.; Sedykh, T.A.; Nevinsky, G.A. Natural Antibodies Produced in Vaccinated Patients and COVID-19 Convalescents Recognize and Hydrolyze Oligopeptides Corresponding to the S-Protein of SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R.A. Antibodies of Predetermined Specificity in Biology and Medicine. Adv. Immunol. 1984, 36, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, S.J.; Jacobs, J.W.; Schultz, P.G. Selective Chemical Catalysis by an Antibody. Science 1986, 234, 1570–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, A.; Janda, K.D.; Lerner, R.A. Catalytic Antibodies. Science 1986, 234, 1566–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, E.A.; Kabirova, E.M.; Sizikov, A.E.; Buneva, V.N.; Nevinsky, G.A. IgGs-Abzymes from the Sera of Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Hydrolyzed MiRNAs. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlassov, A.; Florentz, C.; Helm, M.; Naumov, V.; Buneva, V.; Nevinsky, G.; Giege, R. Characterization and Selectivity of Catalytic Antibodies from Human Serum with RNase Activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998, 26, 5243–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Buneva, V.N.; Nevinsky, G.A. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Molecular Cloning and Analysis of 22 Individual Recombinant Monoclonal Kappa Light Chains Specifically Hydrolyzing Human Myelin Basic Protein. J. Mol. Recognit. 2015, 28, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, H.; Planque, S.; Nishiyama, Y.; Szabo, P.; Weksler, M.E.; Friedland, R.P.; Paul, S. Catalytic Antibodies to Amyloid β Peptide in Defense against Alzheimer Disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 2008, 7, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Planque, S.; Nishiyama, Y. Immunological Origin and Functional Properties of Catalytic Autoantibodies to Amyloid β Peptide. J. Clin. Immunol. 2010, 30, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planque, S.A.; Nishiyama, Y.; Sonoda, S.; Lin, Y.; Taguchi, H.; Hara, M.; Kolodziej, S.; Mitsuda, Y.; Gonzalez, V.; Sait, H.B.R.; et al. Specific Amyloid β Clearance by a Catalytic Antibody Construct. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 10229–10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, H.; Planque, S.; Nishiyama, Y.; Symersky, J.; Boivin, S.; Szabo, P.; Friedland, R.P.; Ramsland, P.A.; Edmundson, A.B.; Weksler, M.E.; et al. Autoantibody-Catalyzed Hydrolysis of Amyloid β Peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 4714–4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Y.; Taguchi, H.; Hara, M.; Planque, S.A.; Mitsuda, Y.; Paul, S. Metal-Dependent Amyloid β-Degrading Catalytic Antibody Construct. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 180, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Aulova, K.S.; Nevinsky, G.A. Modeling Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of Gene-Modified and Induced Animal Models, Complex Cell Culture Models, and Computational Modeling. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timofeeva, A.; Sedykh, S.; Nevinsky, G. Post-Immune Antibodies in HIV-1 Infection in the Context of Vaccine Development: A Variety of Biological Functions and Catalytic Activities. Vaccines 2022, 10, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planque, S.; Nishiyama, Y.; Taguchi, H.; Salas, M.; Hanson, C.; Paul, S. Catalytic Antibodies to HIV: Physiological Role and Potential Clinical Utility. Autoimmun. Rev. 2008, 7, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planque, S.; Mitsuda, Y.; Taguchi, H.; Salas, M.; Morris, M.-K.; Nishiyama, Y.; Kyle, R.; Okhuysen, P.; Escobar, M.; Hunter, R.; et al. Characterization of Gp120 Hydrolysis by IgA Antibodies from Humans without HIV Infection. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2007, 23, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, S.; Planque, S.; Zhou, Y.-X.; Taguchi, H.; Bhatia, G.; Karle, S.; Hanson, C.; Nishiyama, Y. Specific HIV Gp120-Cleaving Antibodies Induced by Covalently Reactive Analog of Gp120. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 20429–20435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uda, T.; Hifumi, E. Super Catalytic Antibody and Antigenase. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2004, 97, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odintsova, E.S.; Dmitrenok, P.S.; Timofeeva, A.M.; Buneva, V.N.; Nevinsky, G.A. Why Specific Anti-Integrase Antibodies from HIV-Infected Patients Can Efficiently Hydrolyze 21-Mer Oligopeptide Corresponding to Antigenic Determinant of Human Myelin Basic Protein. J. Mol. Recognit. 2014, 27, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.; Sedykh, S.; Maksimenko, L.; Sedykh, T.; Skudarnov, S.; Ostapova, T.; Yaschenko, S.; Gashnikova, N.; Nevinsky, G. The Blood of the HIV-Infected Patients Contains κ-IgG, λ-IgG, and Bispecific Κλ-IgG, Which Possess DNase and Amylolytic Activity. Life 2022, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, A. Immune Recognition, Antigen Design, and Catalytic Antibody Production. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1994, 47, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-W.; Xia, L.; Su, Y.; Liu, H.; Xia, X.; Lu, Q.; Yang, C.; Reheman, K. Molecular Imprint of Enzyme Active Site by Camel Nanobodies. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 13713–13721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, L.T.; Bandyopadhyay, P.; Scanlan, T.S.; Kuntz, I.D.; Kollman, P.A. Direct Hydroxide Attack Is a Plausible Mechanism for Amidase Antibody 43C9. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1371–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, F.; Berti, F.; Brady, K.; Colombatti, A.; Pauletto, A.; Pucillo, C.; Thomas, N.R. An Unprecedented Catalytic Motif Revealed in the Model Structure of Amide Hydrolyzing Antibody 312d6. ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-R.; Kim, J.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, W.-R.; Sohn, J.-N.; Chung, Y.-C.; Shim, H.-K.; Lee, S.-C.; Kwon, M.-H.; Kim, Y.-S. Heavy and Light Chain Variable Single Domains of an Anti-DNA Binding Antibody Hydrolyze Both Double- and Single-Stranded DNAs without Sequence Specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 15287–15295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendra, A.; Sharma, M.; Rao, D.N.; Peyron, I.; Planchais, C.; Dimitrov, J.D.; Kaveri, S.V.; Lacroix-Desmazes, S. Antibody-Mediated Catalysis: Induction and Therapeutic Relevance. Autoimmun. Rev. 2013, 12, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Janda, K.D. Catalytic Antibodies: Hapten Design Strategies and Screening Methods. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 5247–5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padiolleau-Lefèvre, S.; Naya, R.B.; Shahsavarian, M.A.; Friboulet, A.; Avalle, B. Catalytic Antibodies and Their Applications in Biotechnology: State of the Art. Biotechnol. Lett. 2014, 36, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friboulet, A.; Izadyar, L.; Avalle, B.; Roseto, A.; Thomas, D. Abzyme Generation Using an Anti-Idiotypic Antibody as the “Internal Image” of an Enzyme Active Site. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1994, 47, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friboulet, A.; Izadyar, L.; Avalle, B.; Roseto, A.; Thomas, D. Antiidiotypic Antibodies as Functional Internal Images of Enzyme—Active Sites. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1995, 750, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalle, B.; Thomas, D.; Friboulet, A. Functional Mimicry: Elicitation of a Monoclonal Antiidiotypic Antibody Hydrolizing Β—Lactams. FASEB J. 1998, 12, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillet, D.; Paon, M.; Vorobiev, I.I.; Gabibov, A.G.; Thomas, D.; Friboulet, A. Idiotypic Network Mimicry and Antibody Catalysis: Lessons for the Elicitation of Efficient Anti-Idiotypic Protease Antibodies. J. Immunol. Methods 2002, 269, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izadyar, L.; Friboulet, A.; Remy, M.H.; Roseto, A.; Thomas, D. Monoclonal Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies as Functional Internal Images of Enzyme Active Sites: Production of a Catalytic Antibody with a Cholinesterase Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 8876–8880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix-Desmazes, S.; Wootla, B.; Delignat, S.; Dasgupta, S.; Nagaraja, V.; Kazatchkine, M.D.; Kaveri, S.V. Pathophysiology of Catalytic Antibodies. Immunol. Lett. 2006, 103, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefevre, S.; Debat, H.; Thomas, D.; Friboulet, A.; Avalle, B. A Suicide—Substrate Mechanism for Hydrolysis of Β—Lactams by an Anti—Idiotypic Catalytic Antibody. FEBS Lett. 2001, 489, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesnikov, A.V.; Kozyr, A.V.; Alexandrova, E.S.; Koralewski, F.; Demin, A.V.; Titov, M.I.; Avalle, B.; Tramontano, A.; Paul, S.; Thomas, D.; et al. Enzyme Mimicry by the Antiidiotypic Antibody Approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13526–13531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamers-Casterman, C.; Atarhouch, T.; Muyldermans, S.; Robinson, G.; Hammers, C.; Songa, E.B.; Bendahman, N.; Hammers, R. Naturally Occurring Antibodies Devoid of Light Chains. Nature 1993, 363, 446–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, M.M.; De Haard, H.J. Properties, Production, and Applications of Camelid Single-Domain Antibody Fragments. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 77, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbel, S. Jerne’s “Immune Network Theory”, of Interacting Anti—Idiotypic Antibodies Applied to Immune Responses during COVID-19 Infection and after COVID-19 Vaccination. BioEssays 2023, 45, e2300071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.M.; Forrest, J.C.; Boehme, K.W.; Kennedy, J.L.; Owens, S.; Herzog, C.; Liu, J.; Harville, T.O. Development of ACE2 Autoantibodies after SARS-CoV-2 Infection. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, W.J.; Longo, D.L. A Possible Role for Anti-Idiotype Antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 394–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Sedykh, S.E.; Nevinsky, G.A. SARS-CoV-2 Infection as a Risk Factor for the Development of Autoimmune Pathology. Mol. Meditsina Mol. Med. 2022, 20, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timofeeva, A.M.; Aulova, K.S.; Mustaev, E.A.; Nevinsky, G.A. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Molecular Mimicry: An Immunoinformatic Screen for Cross-Reactive Autoantigen Candidates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebedin, M.; García, C.V.; Spatt, L.; Ratswohl, C.; Thibeault, C.; Ostendorf, L.; Alexander, T.; Paul, F.; Sander, L.E.; Kurth, F.; et al. Discriminating Promiscuous from Target-specific Autoantibodies in COVID-19. Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 53, 2250210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, E.; Sikora, D.; Poniedziałek, B.; Szymański, K.; Kondratiuk, K.; Żurawski, J.; Brydak, L.; Rzymski, P. IgG Autoantibodies against ACE2 in SARS-CoV-2 Infected Patients. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.P.; Herzog, C.; Vick, L.V.; Nielsen, R.; Harville, Y.I.; Longo, D.L.; Arthur, J.M.; Murphy, W.J. Sequential SARS-CoV-2 MRNA Vaccination Induces Anti-Idiotype (Anti-ACE2) Antibodies in K18 Human ACE2 Transgenic Mice. Vaccines 2025, 13, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerne, N.K. The Somatic Generation of Immune Recognition. Eur. J. Immunol. 1971, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobes, R.; Pareja, E. Could Anti-ACE2 Antibodies Alter the Results of SARS-CoV-2 Ab Neutralization Assays? Immunol. Lett. 2022, 247, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Myers, R.; Mehl, F.; Murphy, L.; Brooks, B.; Wilson, J.M.; Kadl, A.; Woodfolk, J.; Zeichner, S.L. ACE-2-like Enzymatic Activity Is Associated with Immunoglobulin in COVID-19 Patients. MBio 2024, 15, e0054124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, J.M. Antibodies to Watch in 2017. MAbs 2017, 9, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecker, D.M.; Jones, S.D.; Levine, H.L. The Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibody Market. MAbs 2015, 7, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagassé, H.A.D.; Alexaki, A.; Simhadri, V.L.; Katagiri, N.H.; Jankowski, W.; Sauna, Z.E.; Kimchi-Sarfaty, C. Recent Advances in (Therapeutic Protein) Drug Development. F1000Research 2017, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schouwenburg, P.A.; Rispens, T.; Wolbink, G.J. Immunogenicity of Anti-TNF Biologic Therapies for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2013, 9, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atzeni, F.; Talotta, R.; Salaffi, F.; Cassinotti, A.; Varisco, V.; Battellino, M.; Ardizzone, S.; Pace, F.; Sarzi-Puttini, P. Immunogenicity and Autoimmunity during Anti-TNF Therapy. Autoimmun. Rev. 2013, 12, 703–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, A.S.; Scott, D.W. Immunogenicity of Protein Therapeutics. Trends Immunol. 2007, 28, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vennegoor, A.; Rispens, T.; Strijbis, E.M.; Seewann, A.; Uitdehaag, B.M.; Balk, L.J.; Barkhof, F.; Polman, C.H.; Wolbink, G.; Killestein, J. Clinical Relevance of Serum Natalizumab Concentration and Anti-Natalizumab Antibodies in Multiple Sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2013, 19, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolbink, G.J.; Vis, M.; Lems, W.; Voskuyl, A.E.; De Groot, E.; Nurmohamed, M.T.; Stapel, S.; Tak, P.P.; Aarden, L.; Dijkmans, B. Development of Antiinfliximab Antibodies and Relationship to Clinical Response in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radstake, T.R.D.J.; Svenson, M.; Eijsbouts, A.M.; van den Hoogen, F.H.J.; Enevold, C.; van Riel, P.L.C.M.; Bendtzen, K. Formation of Antibodies against Infliximab and Adalimumab Strongly Correlates with Functional Drug Levels and Clinical Responses in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 1739–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelds, G.M. Development of Antidrug Antibodies Against Adalimumab and Association with Disease Activity and Treatment Failure During Long-Term Follow-Up. JAMA 2011, 305, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecluse, L.L.A.; Driessen, R.J.B.; Spuls, P.I.; de Jong, E.M.G.J.; Stapel, S.O.; van Doorn, M.B.A.; Bos, J.D.; Wolbink, G.-J. Extent and Clinical Consequences of Antibody Formation Against Adalimumab in Patients with Plaque Psoriasis. Arch. Dermatol. 2010, 146, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, T.T.; Kropshofer, H.; Singer, T.; Mitchell, J.A.; George, A.J.T. The Safety and Side Effects of Monoclonal Antibodies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, V.; Balsa, A.; Al-Saleh, J.; Barile-Fabris, L.; Horiuchi, T.; Takeuchi, T.; Lula, S.; Hawes, C.; Kola, B.; Marshall, L. Immunogenicity of Biologics in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: A Systematic Review. BioDrugs 2017, 31, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorovits, B.; Baltrukonis, D.J.; Bhattacharya, I.; Birchler, M.A.; Finco, D.; Sikkema, D.; Vincent, M.S.; Lula, S.; Marshall, L.; Hickling, T.P. Immunoassay Methods Used in Clinical Studies for the Detection of Anti-Drug Antibodies to Adalimumab and Infliximab. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2018, 192, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davda, J.; Declerck, P.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; Hickling, T.P.; Jacobs, I.A.; Chou, J.; Salek-Ardakani, S.; Kraynov, E. Immunogenicity of Immunomodulatory, Antibody-Based, Oncology Therapeutics. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enrico, D.; Paci, A.; Chaput, N.; Karamouza, E.; Besse, B. Antidrug Antibodies Against Immune Checkpoint Blockers: Impairment of Drug Efficacy or Indication of Immune Activation? Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 787–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vugt, M.J.H.; Stone, J.A.; De Greef, H.J.M.M.; Snyder, E.S.; Lipka, L.; Turner, D.C.; Chain, A.; Lala, M.; Li, M.; Robey, S.H.; et al. Immunogenicity of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Advanced Tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Yamanaka, H.; Takeuchi, T.; Inoue, M.; Saito, K.; Saeki, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Nambu, Y. Safety and Efficacy of CT-P13 in Japanese Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis in an Extension Phase or after Switching from Infliximab. Mod. Rheumatol. 2017, 27, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krintel, S.B.; Grunert, V.P.; Hetland, M.L.; Johansen, J.S.; Rothfuss, M.; Palermo, G.; Essioux, L.; Klause, U. The Frequency of Anti-Infliximab Antibodies in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Treated in Routine Care and the Associations with Adverse Drug Reactions and Treatment Failure. Rheumatology 2013, 52, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.S.; Lloyd, S.B.; Lee, W.S.; Kristensen, A.B.; Amarasena, T.; Center, R.J.; Keele, B.F.; Lifson, J.D.; LaBranche, C.C.; Montefiori, D.; et al. Partial Efficacy of a Broadly Neutralizing Antibody against Cell-Associated SHIV Infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaaf1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, M.B.; Cheever, T.; Malherbe, D.C.; Pandey, S.; Reed, J.; Yang, E.S.; Wang, K.; Pegu, A.; Chen, X.; Siess, D.; et al. Single-Dose BNAb Cocktail or Abbreviated ART Post-Exposure Regimens Achieve Tight SHIV Control without Adaptive Immunity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, M.S.; Lee, W.S.; Kristensen, A.B.; Amarasena, T.; Khoury, G.; Wheatley, A.K.; Reynaldi, A.; Wines, B.D.; Hogarth, P.M.; Davenport, M.P.; et al. Fc-Dependent Functions Are Redundant to Efficacy of Anti-HIV Antibody PGT121 in Macaques. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 129, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.S.; Reynaldi, A.; Amarasena, T.; Davenport, M.P.; Parsons, M.S.; Kent, S.J. Anti-Drug Antibodies in Pigtailed Macaques Receiving HIV Broadly Neutralising Antibody PGT121. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 749891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakelee, H.A.; Patnaik, A.; Sikic, B.I.; Mita, M.; Fox, N.L.; Miceli, R.; Ullrich, S.J.; Fisher, G.A.; Tolcher, A.W. Phase I and Pharmacokinetic Study of Lexatumumab (HGS-ETR2) given Every 2 Weeks in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinberg, D.A.; Straus, D.J.; Yeh, S.D.; Divgi, C.; Garin-Chesa, P.; Graham, M.; Pentlow, K.; Coit, D.; Oettgen, H.F.; Old, L.J. A Phase I Toxicity, Pharmacology, and Dosimetry Trial of Monoclonal Antibody OKB7 in Patients with Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Effects of Tumor Burden and Antigen Expression. J. Clin. Oncol. 1990, 8, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.J.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Pili, R.; Denmeade, S.R.; Rathkopf, D.; Slovin, S.F.; Farrelly, J.; Chudow, J.J.; Vincent, M.; Scher, H.I.; et al. A Phase I/IIA Study of AGS-PSCA for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2714–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, R.; Attard, G.; Pacey, S.; Li, L.; Razak, A.; Perrett, R.; Barrett, M.; Judson, I.; Kaye, S.; Fox, N.L.; et al. Phase 1 and Pharmacokinetic Study of Lexatumumab in Patients with Advanced Cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 6187–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künzel, C.; Abdolzade-Bavil, A.; Engel, A.M.; Pleitner, M.; Schick, E.; Stubenrauch, K. Assay Concept for Detecting Anti-Drug IgM in Human Serum Samples by Using a Novel Recombinant Human IgM Positive Control. Bioanalysis 2021, 13, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Brummelen, E.M.J.; Ros, W.; Wolbink, G.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H.M. Antidrug Antibody Formation in Oncology: Clinical Relevance and Challenges. Oncologist 2016, 21, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, H.; Ikeda, M.; Okusaka, T.; Inaba, Y.; Iguchi, H.; Yagawa, K.; Yamamoto, N. A Phase I Study of MEDI-575, a PDGFRα Monoclonal Antibody, in Japanese Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015, 76, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasche, L.; Duell, J.; Castro, I.C.; Dubljevic, V.; Chatterjee, M.; Knop, S.; Hensel, F.; Rosenwald, A.; Einsele, H.; Topp, M.S.; et al. GRP78-Directed Immunotherapy in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma—Results from a Phase 1 Trial with the Monoclonal Immunoglobulin M Antibody PAT-SM6. Haematologica 2015, 100, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, A.; Meredith, R.F.; Khazaeli, M.B.; Shen, S.; Grizzle, W.E.; Carey, D.; Busby, E.; LoBuglio, A.F.; Robert, F. Phase I Study of 90 Y-CC49 Monoclonal Antibody Therapy in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Effect of Chelating Agents and Paclitaxel Co-Administration. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2005, 20, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiorean, E.G.; Hurwitz, H.I.; Cohen, R.B.; Schwartz, J.D.; Dalal, R.P.; Fox, F.E.; Gao, L.; Sweeney, C.J. Phase I Study of Every 2- or 3-Week Dosing of Ramucirumab, a Human Immunoglobulin G1 Monoclonal Antibody Targeting the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitman, R.J.; Tallman, M.S.; Robak, T.; Coutre, S.; Wilson, W.H.; Stetler-Stevenson, M.; FitzGerald, D.J.; Lechleider, R.; Pastan, I. Phase I Trial of Anti-CD22 Recombinant Immunotoxin Moxetumomab Pasudotox (CAT-8015 or HA22) in Patients with Hairy Cell Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulskis, A.; Yeung, D.; Subramanyam, M.; Amaravadi, L. Solution ELISA as a Platform of Choice for Development of Robust, Drug Tolerant Immunogenicity Assays in Support of Drug Development. J. Immunol. Methods 2011, 365, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeijsters, E.H.; van der Elst, K.C.M.; Visch, A.; Göbel, C.; Loeff, F.C.; Rispens, T.; Huitema, A.D.R.; van Luin, M.; El Amrani, M. Optimization of a Quantitative Anti-Drug Antibodies against Infliximab Assay with the Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry: A Method Validation Study and Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depraetere, H.; Depla, E.; Haelewyn, J.; De Ley, M. An Anti-idiotypic Antibody with an Internal Image of Human Interferon-γ and Human Interferon-γ-like Antiviral Activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 2260–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, M.R.; Windsor, W.T.; Nagabhushan, T.L.; Lundell, D.J.; Lunn, C.A.; Zauodny, P.J.; Narula, S.K. Crystal Structure of a Complex between Interferon-γ and Its Soluble High-Affinity Receptor. Nature 1995, 376, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elazar, Z.; Kanety, H.; Schreiber, M.; Fuchs, S. Anti-Idiotypes against a Monoclonal Anti-Haloperidol Antibody Bind to Dopamine Receptor. Life Sci. 1988, 42, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, H.; Liu, K.; Hsiung, S.; Yu, P.; Kirchgessner, A.L.; Gershon, M.D. Identification of Serotonin Receptors Recognized by Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies. J. Neurochem. 1991, 57, 930–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sege, K.; Peterson, P.A. Use of Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies as Cell-Surface Receptor Probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 2443–2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, G.; Amir-Zaltsman, Y.; Barnard, G.; Kohen, F. Characterization of an Antiidiotypic Antibody Mimicking the Actions of Estradiol and Its Interaction with Estrogen Receptors. Endocrinology 1992, 130, 3633–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.-N.; Jiang, H.-L.; Li, W.; Wu, T.-C.; Hong, P.; Li, Y.M.; Zhang, H.; Cui, H.-Z.; Zheng, X. Development and Characterization of a Novel Anti-Idiotypic Monoclonal Antibody to Growth Hormone, Which Can Mimic Physiological Functions of Growth Hormone in Primary Porcine Hepatocytes. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coscia, C.J.; Szücs, M.; Barg, J.; Belcheva, M.M.; Bem, W.T.; Khoobehi, K.; Donnigan, T.A.; Juszczak, R.; McHale, R.J.; Hanley, M.R.; et al. A Monoclonal Anti-Idiotypic Antibody to μ and δ Opioid Receptors. Mol. Brain Res. 1991, 9, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasel, J.A.; Pelosi, L.A. Morphine-Mimetic Anti-Paratypic Antibodies: Cross-Reactive Properties. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986, 136, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.; Segre, M. Inhibition of Cocaine Binding to the Human Dopamine Transporter by a Single Chain Anti-Idiotypic Antibody: Its Cloning, Expression, and Functional Properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol. Basis Dis. 2003, 1638, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, A.; Rahman, S.U.; Arshad, M.I.; Aslam, B. Immune Modulatory Potential of Anti-Idiotype Antibodies as a Surrogate of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus Antigen. mSphere 2018, 3, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerink, M.A.J.; Apicella, M. Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies as Vaccines against Carbohydrate Antigens. Springer Semin. Immunopathol. 1993, 15, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhou, L.; Wang, D. Functional Mimicry of an Anti-idiotypic Antibody to Nominal Antigen on Cellular Response. Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 2002, 93, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbaum, F.A.; Velikovsky, C.A.; Dall’Acqua, W.; Fossati, C.A.; Fields, B.A.; Braden, B.C.; Poljak, R.J.; Mariuzza, R.A. Characterization of Anti-Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies That Bind Antigen and an Anti-Idiotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 8697–8701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, A.; Hakomori, S. Molecular Changes in Carbohydrate Antigens Associated with Cancer. BioEssays 1990, 12, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheever, M.A.; Allison, J.P.; Ferris, A.S.; Finn, O.J.; Hastings, B.M.; Hecht, T.T.; Mellman, I.; Prindiville, S.A.; Viner, J.L.; Weiner, L.M.; et al. The Prioritization of Cancer Antigens: A National Cancer Institute Pilot Project for the Acceleration of Translational Research. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 5323–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, T.; Cahan, L.D.; Tsuchida, T.; Saxton, R.E.; Irie, R.F.; Morton, D.L. Immunogenicity of Melanoma-associated Gangliosides in Cancer Patients. Int. J. Cancer 1985, 35, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lardone, R.D.; Alaniz, M.E.; Irazoqui, F.J.; Nores, G.A. Unusual Presence of Anti-GM1 IgG-Antibodies in a Healthy Individual, and Their Possible Involvement in the Origin of Disease-Associated Anti-GM1 Antibodies. J. Neuroimmunol. 2006, 173, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retter, M.W.; Johnson, J.C.; Peckham, D.W.; Bannink, J.E.; Bangur, C.S.; Dresser, K.; Cai, F.; Foy, T.M.; Fanger, N.A.; Fanger, G.R.; et al. Characterization of a Proapoptotic Antiganglioside GM2 Monoclonal Antibody and Evaluation of Its Therapeutic Effect on Melanoma and Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Xenografts. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 6425–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aixinjueluo, W.; Furukawa, K.; Zhang, Q.; Hamamura, K.; Tokuda, N.; Yoshida, S.; Ueda, R.; Furukawa, K. Mechanisms for the Apoptosis of Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells Induced by Anti-GD2 Monoclonal Antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 29828–29836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollert, M.; David, K.; Vollmert, C.; Juhl, H.; Erttmann, R.; Bredehorst, R.; Vogel, C.-W. Mechanisms of in Vivo Antineuroblastoma Activity of Human Natural IgM. Eur. J. Cancer 1997, 33, 1942–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, P.B.; Houghton, A.N. Induction of IgG Antibodies against GD3 Ganglioside in Rabbits by an Anti-Idiotypic Monoclonal Antibody. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 88, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, G.; Chakraborty, M.; Foon, K.A.; Reisfeld, R.A.; Bhattacharya-Chatterjee, M. Induction of IgG Antibodies by an Anti-Idiotype Antibody Mimicking Disialoganglioside GD2. J. Immunother. 1998, 21, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foon, K.A.; Lutzky, J.; Baral, R.N.; Yannelli, J.R.; Hutchins, L.; Teitelbaum, A.; Kashala, O.L.; Das, R.; Garrison, J.; Reisfeld, R.A.; et al. Clinical and Immune Responses in Advanced Melanoma Patients Immunized with an Anti-Idiotype Antibody Mimicking Disialoganglioside GD2. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, A.; Mier, E.S.; Vispo, N.S.; Vazquez, A.M.; Perez Rodríguez, R. A Monoclonal Antibody against NeuGc-Containing Gangliosides Contains a Regulatory Idiotope Involved in the Interaction with B and T Cells. Mol. Immunol. 2002, 39, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A.; Alfonso, M.; Alonso, R.; Saurez, G.; Troche, M.; Catalá, M.; Díaz, R.M.; Pérez, R.; Vázquez, A.M. Immune Responses in Breast Cancer Patients Immunized with an Anti-Idiotype Antibody Mimicking NeuGc-Containing Gangliosides. Clin. Immunol. 2003, 107, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neninger, E.; Diaz, R.M.; de la Torre, A.; Rives, R.; Diaz, A.; Saurez, G.; Gabri, M.R.; Alonso, D.F.; Wilkinson, B.; Alfonso, A.M.; et al. Active Immunotherapy with 1E10 Anti-Idiotype Vaccine in Patients with Small Cell Lung Cancer: Report of a Phase I Trial. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2007, 6, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A.M.; Toledo, D.; Martínez, D.; Griñán, T.; Brito, V.; Macías, A.; Alfonso, S.; Rondón, T.; Suárez, E.; Vázquez, A.M.; et al. Characterization of the Antibody Response against NeuGcGM3 Ganglioside Elicited in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients Immunized with an Anti-Idiotype Antibody. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 6625–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonso, S.; Valdés-Zayas, A.; Santiesteban, E.R.; Flores, Y.I.; Areces, F.; Hernández, M.; Viada, C.E.; Mendoza, I.C.; Guerra, P.P.; García, E.; et al. A Randomized, Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of Racotumomab-Alum Vaccine as Switch Maintenance Therapy in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 3660–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ko, E.C.; Peng, L.; Gillies, S.D.; Ferrone, S. Human High Molecular Weight Melanoma-Associated Antigen Mimicry by Mouse Anti-Idiotypic Monoclonal Antibody MK2-23: Enhancement of Immunogenicity of Anti-Idiotypic Monoclonal Antibody MK2-23 by Fusion with Interleukin 2. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 6976–6983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelman, A.; Chen, Z.J.; Kageshita, T.; Yang, H.; Yamada, M.; Baskind, P.; Goldberg, N.; Puccio, C.; Ahmed, T.; Arlin, Z. Active Specific Immunotherapy in Patients with Melanoma. A Clinical Trial with Mouse Antiidiotypic Monoclonal Antibodies Elicited with Syngeneic Anti-High-Molecular-Weight-Melanoma-Associated Antigen Monoclonal Antibodies. J. Clin. Investig. 1990, 86, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, U.; Schlebusch, H.; Köhler, S.; Schmolling, J.; Grünn, U.; Krebs, D. Immunological Responses to the Tumor-Associated Antigen CA15 in Patients with Advanced Ovarian Cancer Induced by the Murine Monoclonal Anti-Idiotype Vaccine ACA125. Hybridoma 1997, 16, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M.B.; Foon, K.A.; Köhler, H. Idiotypic Antibody Immunotherapy of Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 1994, 38, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, G.; Bhatnagar, A.; Cunningham, D.; Cosgriff, T.M.; Harper, P.G.; Steward, W.; Bridgewater, J.; Moore, M.; Cassidy, J.; Coleman, R.; et al. Phase III Trial of 5-Fluorouracil and Leucovorin plus Either 3H1 Anti-Idiotype Monoclonal Antibody or Placebo in Patients with Advanced Colorectal Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2006, 17, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, G.W.L.; Durrant, L.G.; Hardcastle, J.D.; Austin, E.B.; Sewell, H.F.; Robins, R.A. Clinical Outcome of Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated with Human Monoclonal Anti-idiotypic Antibody. Int. J. Cancer 1994, 57, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell-Armstrong, C.A.; Durrant, L.G.; Buckley, T.J.D.; Scholefield, J.H.; Robins, R.A.; Fielding, K.; Monson, J.R.T.; Guillou, P.; Calvert, H.; Carmichael, J.; et al. Randomized Double-Blind Phase II Survival Study Comparing Immunization with the Anti-Idiotypic Monoclonal Antibody 105AD7 against Placebo in Advanced Colorectal Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2001, 84, 1443–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Libera, M.; Caputo, V.; Laterza, G.; Moudoud, L.; Soggiu, A.; Bonizzi, L.; Diotti, R.A. The Question of HIV Vaccine: Why Is a Solution Not Yet Available? J. Immunol. Res. 2024, 2024, 2147912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, W.J.W.; Gaston, I.; Anderson, T.; Haigwood, N.; McGrath, M.S.; Rosen, J.; Steimer, K.S. Anti-Idiotypic Antisera Raised Against Monoclonal Aritibody Specific for a P24 Gag Region Epitope Detects a Common Interspecies Idiotype Associated with Anti-HIV Responses. Viral Immunol. 1990, 3, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohmann, A.; Peters, V.; Comacchio, R.; Bradley, J. Mouse Monoclonal Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies to HIV P24: Immunochemical Properties and Internal Imagery. Mol. Immunol. 1993, 30, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corre, J.; Février, M.; Thèze, J.; Zouali, M.; Chamaret, S. Anti-idiotypic Antibodies to Human Anti-gp120 Antibodies Bind Recombinant and Cellular Human CD4. Eur. J. Immunol. 1991, 21, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burioni, R.; Mancini, N.; De Marco, D.; Clementi, N.; Perotti, M.; Nitti, G.; Sassi, M.; Canducci, F.; Shvela, K.; Bagnarelli, P.; et al. Anti-HIV-1 Response Elicited in Rabbits by Anti-Idiotype Monoclonal Antibodies Mimicking the CD4-Binding Site. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, A.; Kunert, R. Evaluation of the Potency of the Anti-Idiotypic Antibody Ab2/3H6 Mimicking Gp41 as an HIV-1 Vaccine in a Rabbit Prime/Boost Study. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, V.; Negri, I.; Moudoud, L.; Libera, M.; Bonizzi, L.; Clementi, M.; Diotti, R.A. Anti-HIV Humoral Response Induced by Different Anti-Idiotype Antibody Formats: An In Silico and In Vivo Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, S.; Margolin, D.H.; Min, G.; Lou, D.; Nara, P.; Axthelm, M.K.; Kohler, H. Stimulation of Antiviral Antibody Response in SHIV-IIIB-Infected Macaques. Scand. J. Immunol. 2001, 54, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosenovic, P.; Pettersson, A.-K.; Wall, A.; Thientosapol, E.S.; Feng, J.; Weidle, C.; Bhullar, K.; Kara, E.E.; Hartweger, H.; Pai, J.A.; et al. Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies Elicit Anti-HIV-1–Specific B Cell Responses. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 2316–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya-Chatterjee, M.; Chatterjee, S.K.; Foon, K.A. Anti-Idiotype Vaccine against Cancer. Immunol. Lett. 2000, 74, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, H.; Pashov, A.; Kieber-Emmons, T. The Promise of Anti-Idiotype Revisited. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higano, C.S.; Small, E.J.; Schellhammer, P.; Yasothan, U.; Gubernick, S.; Kirkpatrick, P.; Kantoff, P.W. Sipuleucel-T. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 513–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Amrani, M.; Szanto, C.L.; Hack, C.E.; Huitema, A.D.R.; Nierkens, S.; van Maarseveen, E.M. Quantification of Total Dinutuximab Concentrations in Neuroblastoma Patients with Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018, 410, 5849–5858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkaynak, M.F. Dinutuximab in the Treatment of Neuroblastoma. Expert Opin. Orphan Drugs 2017, 5, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spertini, F.; Leimgruber, A.; Morel, B.; Khazaeli, M.B.; Yamamoto, K.; Dayer, J.M.; Weisbart, R.H.; Lee, M.L. Idiotypic Vaccination with a Murine Anti-DsDNA Antibody: Phase I Study in Patients with Nonactive Systemic Lupus Erythematosus with Nephritis. J. Rheumatol. 1999, 26, 2602–2608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lipman, N.S.; Jackson, L.R.; Trudel, L.J.; Weis-Garcia, F. Monoclonal Versus Polyclonal Antibodies: Distinguishing Characteristics, Applications, and Information Resources. ILAR J. 2005, 46, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foon, K.A.; Chakraborty, M.; John, W.J.; Sherratt, A.; Köhler, H.; Bhattacharya-Chatterjee, M. Immune Response to the Carcinoembryonic Antigen in Patients Treated with an Anti-Idiotype Antibody Vaccine. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 96, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Eck, S.; Gutzmer, R.; Smith, A.J.; Birebent, B.; Purev, E.; Staib, L.; Somasundaram, R.; Zaloudik, J.; Li, W.; et al. Colorectal Cancer Vaccines: Antiidiotypic Antibody, Recombinant Protein, and Viral Vector. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 910, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Status | Antibody | Official Title | Conditions | Last Update Posted | ClinicalTrials.gov ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed | BEC2 | The SILVA Study: Survival in an International Phase III Prospective Randomized LD Small Cell Lung Cancer Vaccination Study with Adjuvant BEC2 and BCG | Lung Cancer | 6 March 2012 | NCT00003279 |

| Unknown status | Racotumomab | A Prospective, Randomized, Multicenter, Open Label Phase III Study of Active Specific Immunotherapy with Racotumomab Plus Best Support Treatment Versus Best Support Treatment in Patients with Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. | NSCLC Lung Cancer, Non-small Cell | 29 July 2016 | NCT01460472 |

| Completed | 3H1 | Phase II Study of Postoperative Adjuvant Immunotherapy and Radiation in Patients with Completely Resected Stage II and Stage IIIA Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Lung Cancer | 13 August 2013 | NCT00006470 |

| Completed | ACA-125 | A Phase I/II Trial of ACA 125 in Patients with Recurrent Epithelial Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Peritoneal Cancer | Ovarian Cancer Fallopian Tube Neoplasms Peritoneal Neoplasms | 2 October 2006 | NCT00103545 |

| Completed | ACA-125 | Phase I Trial of the Monoclonal Anti-Idiotype Antibody ACA125 in Patients with Epithelial Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, or Peritoneal Cancer | Fallopian Tube Cancer Ovarian Cancer Primary Peritoneal Cavity Cancer | 5 June 2013 | NCT00058435 |

| Unknown status | 105AD7 | A Phase I/II Trial of an Allogeneic Cell-Based Vaccine and an Anti-Idiotypic Antibody Vaccine Approach for Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Colon or Rectum | Colorectal Cancer | 20 September 2013 | NCT00007826 |

| Completed | 4B5 | A Phase I/II Trial of a Human Anti-Idiotypic Monoclonal Antibody Vaccine (4B5) Which Mimics the GD2 Antigen, in Patients with Melanoma | Melanoma (Skin) | 12 April 2013 | NCT00004184 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Timofeeva, A.M.; Sedykh, S.E.; Nevinsky, G.A. Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Immune Regulation and Disease: Therapeutic Promise for Next-Generation Vaccines. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121224

Timofeeva AM, Sedykh SE, Nevinsky GA. Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Immune Regulation and Disease: Therapeutic Promise for Next-Generation Vaccines. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121224

Chicago/Turabian StyleTimofeeva, Anna M., Sergey E. Sedykh, and Georgy A. Nevinsky. 2025. "Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Immune Regulation and Disease: Therapeutic Promise for Next-Generation Vaccines" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121224

APA StyleTimofeeva, A. M., Sedykh, S. E., & Nevinsky, G. A. (2025). Anti-Idiotypic Antibodies in Immune Regulation and Disease: Therapeutic Promise for Next-Generation Vaccines. Vaccines, 13(12), 1224. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121224