Oral Administration of MVA-Vectored Vaccines Induces Robust, Long-Lasting Neutralizing Antibody Responses and Provides Complete Protection Against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice, Minks, and Cats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses and Cells

2.2. Redesign and Immunogenicity of the Prefusion-Stabilized S Proteins

2.3. Construction of Recombinant Viruses

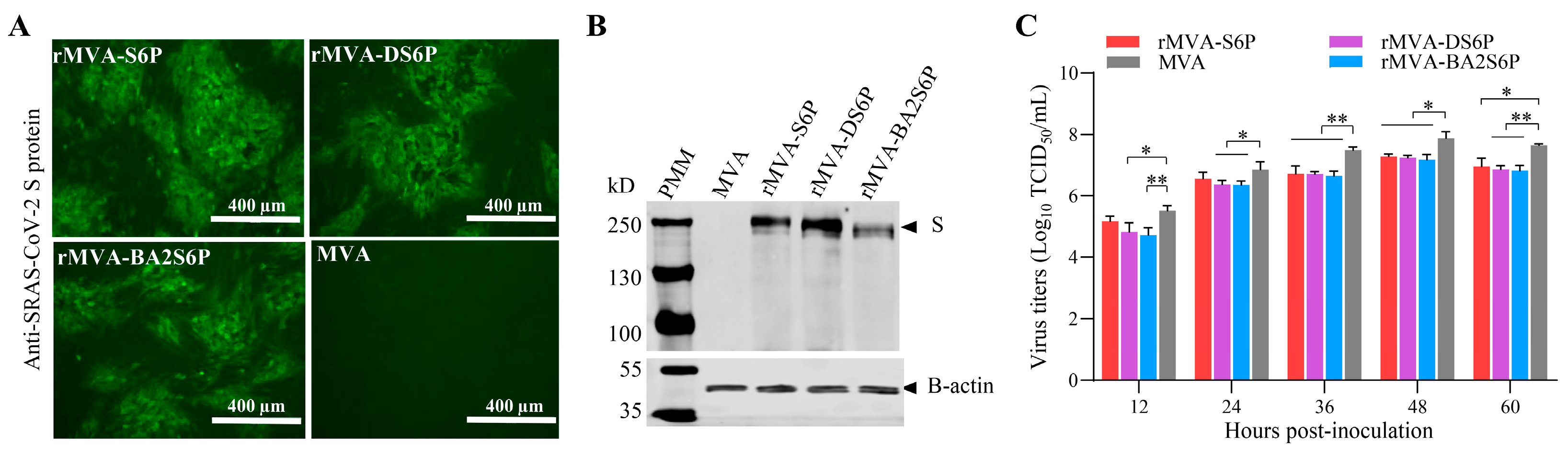

2.4. Confirmation of the SARS-CoV-2 S Gene Expression in Cells Infected with Recombinant MVAs

2.5. Growth Properties of the Recombinant MVAs

2.6. Ethics Statement

2.7. Pathogenicity in Mice

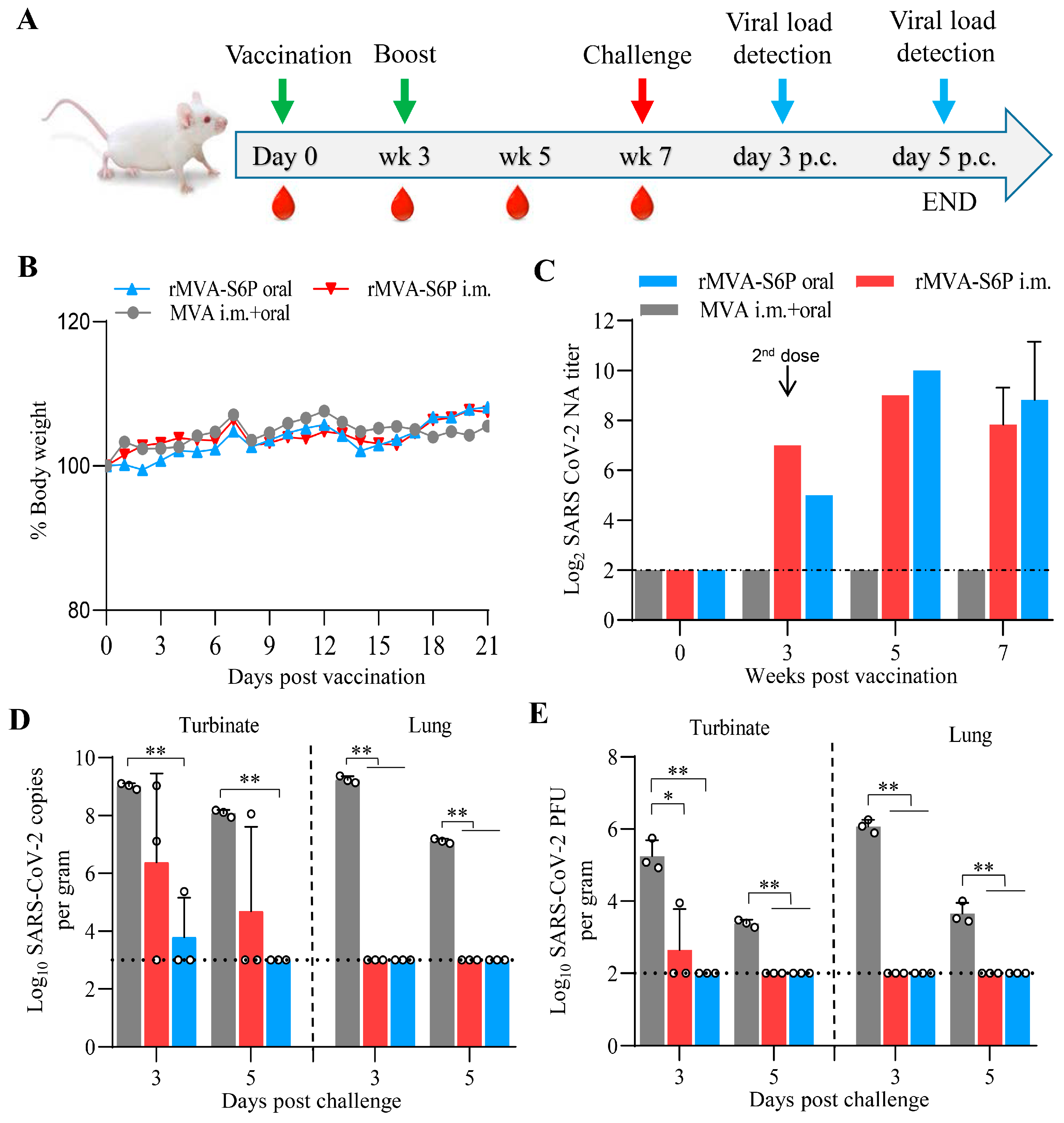

2.8. Immunization Study

2.9. Challenge Test

2.10. Serological Tests

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. COVID-19 DNA Vaccines Expressing S6P, DS6P, and BA2S6P Proteins Are Highly Immunogenic in Mice

3.2. Generation of Recombinant MVAs Expressing the S Genes of SARS-CoV-2

3.3. Introduction and Expression of SARS-CoV-2 S Genes Do Not Increase the Virulence of the MVA Vector in Mice

3.4. Recombinant Virus rMVA-S6P Elicits a Robust NA Response and Provides Complete Protection Against the SARS-CoV-2 Challenge in Mice

3.5. Combined Immunization with These Recombinant MVAs Did Not Compromise the Immunogenicity of Each Recombinant MVA in Mice

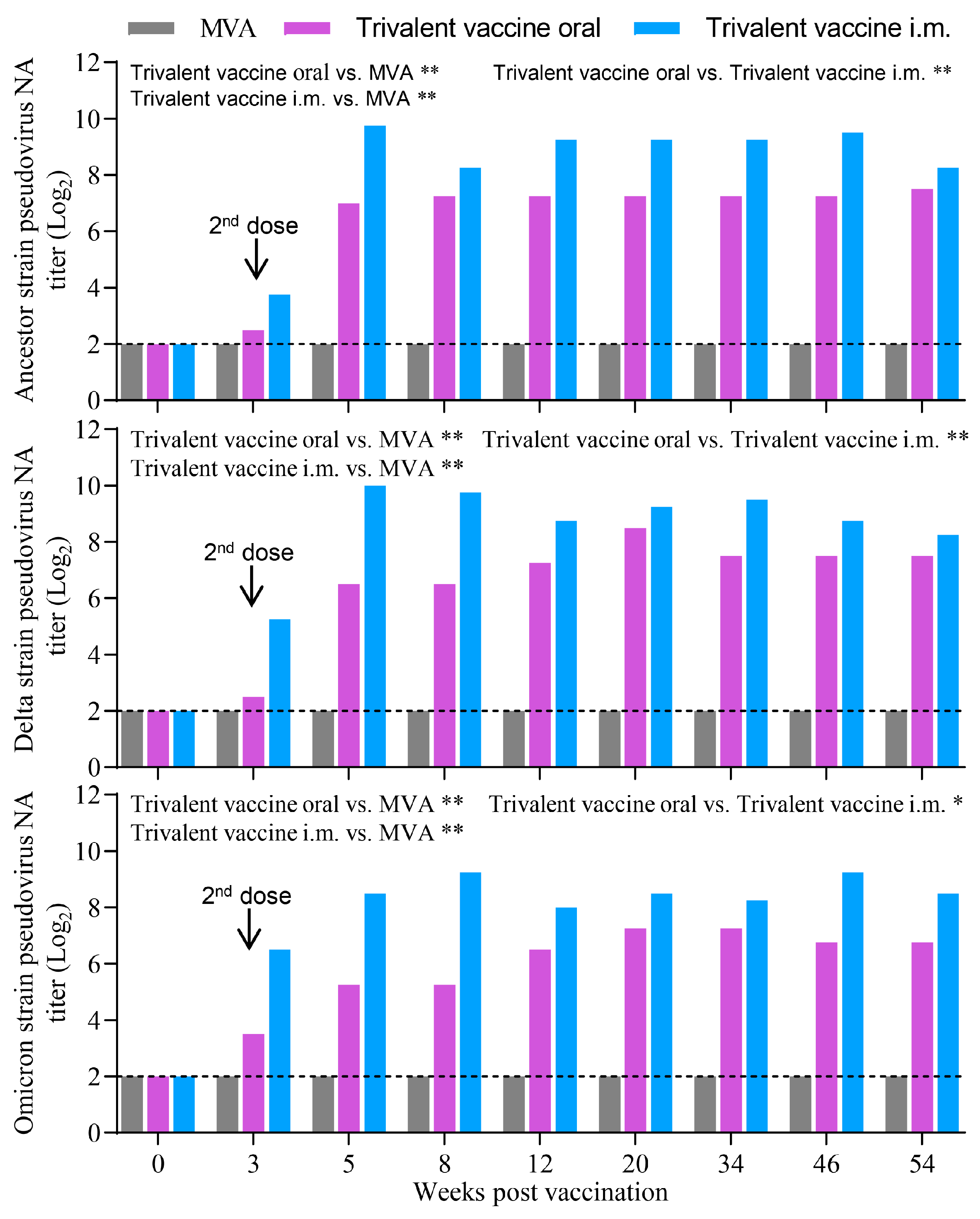

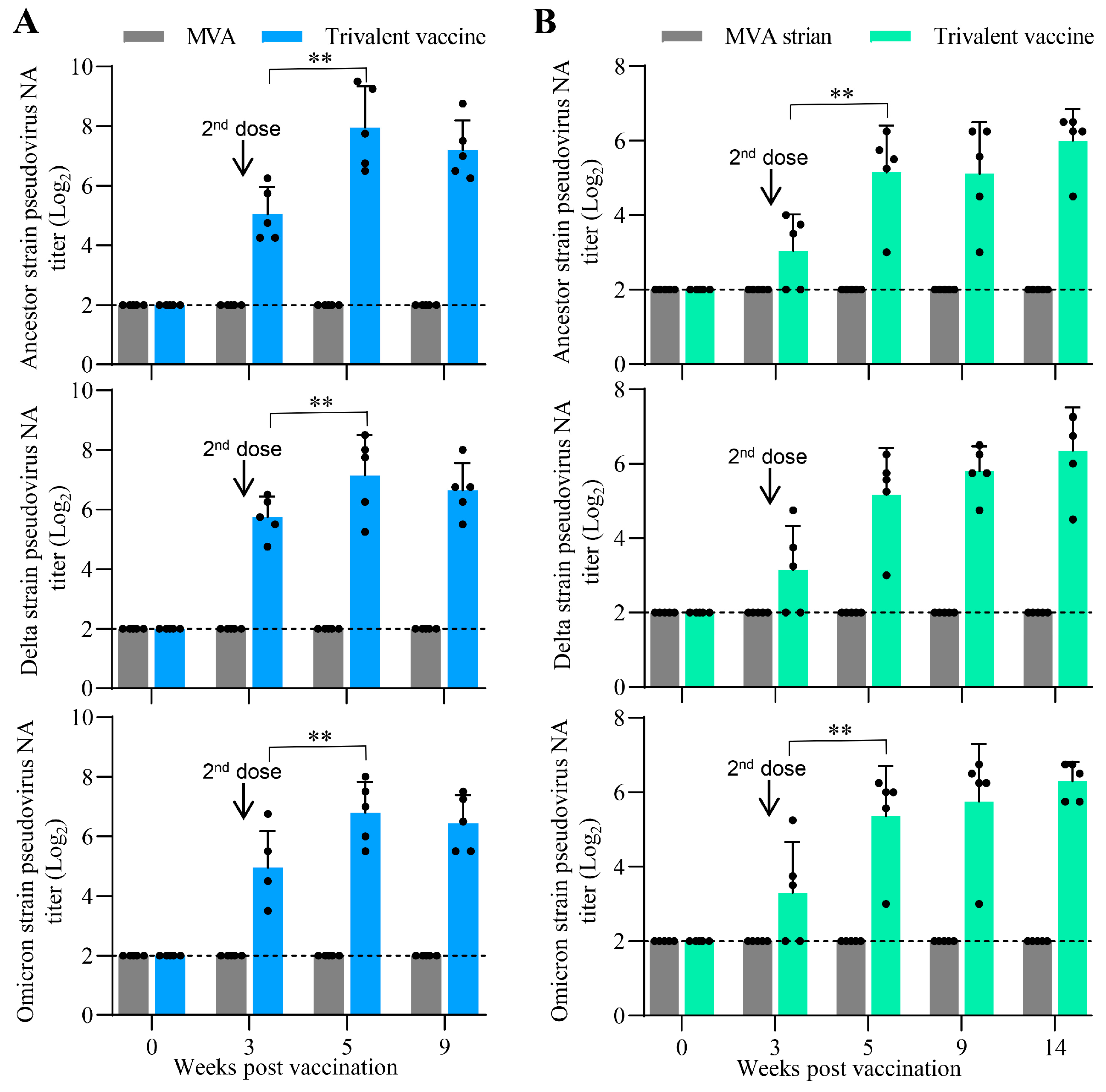

3.6. Oral Vaccination with the Trivalent Vaccine Induced a Robust Neutralizing Antibody Response Against SARS-CoV-2 Pseudovirus in Minks and Cats

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, J.Z.; Wen, Z.Y.; Zhong, G.X.; Yang, H.L.; Wang, C.; Huang, B.Y.; Liu, R.Q.; He, X.J.; Shuai, L.; Sun, Z.R.; et al. Susceptibility of Ferrets, Cats, Dogs, and Other Domesticated Animals to Sars-Coronavirus 2. Science 2020, 368, 1016–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Zhong, G.X.; Yuan, Q.; Wen, Z.Y.; Wang, C.; He, X.J.; Liu, R.Q.; Wang, J.L.; Zhao, Q.J.; Liu, Y.X.; et al. Replication, Pathogenicity, and Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Minks. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwaa291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcbride, D.S.; Garushyants, S.K.; Franks, J.; Magee, A.F.; Overend, S.H.; Huey, D.; Williams, A.M.; Faith, S.A.; Kandeil, A.; Trifkovic, S.; et al. Accelerated Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in Free-Ranging White-Tailed Deer. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WOAH. SARS-CoV-2 in Animals-Situation Report 22; WOAH: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Enserink, M. Coronavirus Rips through Dutch Mink Farms, Triggering Culls. Science 2020, 368, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oreshkova, N.; Molenaar, R.J.; Vreman, S.; Harders, F.; Munnink, B.B.O.; Hakze-van Der Honing, R.W.; Gerhards, N.; Tolsma, P.; Bouwstra, R.; Sikkema, R.S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Farmed Minks, the Netherlands, April and May 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2001005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preska Steinberg, A.; Silander, O.K.; Kussell, E. Correlated Substitutions Reveal Sars-Like Coronaviruses Recombine Frequently with a Diverse Set of Structured Gene Pools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2206945119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arevalo-Romero, J.A.; Chingate-Lopez, S.M.; Camacho, B.A.; Almeciga-Diaz, C.J.; Ramirez-Segura, C.A. Next-Generation Treatments: Immunotherapy and Advanced Therapies for COVID-19. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.J.; Rouphael, N.G.; Widge, A.T.; Jackson, L.A.; Roberts, P.C.; Makhene, M.; Chappell, J.D.; Denison, M.R.; Stevens, L.J.; Pruijssers, A.J.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Mrna-1273 Vaccine in Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2427–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, K.S.; Edwards, D.K.; Leist, S.R.; Abiona, O.M.; Boyoglu-Barnum, S.; Gillespie, R.A.; Himansu, S.; Schäfer, A.; Ziwawo, C.T.; DiPiazza, A.T.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Mrna Vaccine Design Enabled by Prototype Pathogen Preparedness. Nature 2020, 586, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.O.; Kafai, N.M.; Dmitriev, I.P.; Fox, J.M.; Smith, B.K.; Harvey, I.B.; Chen, R.E.; Winkler, E.S.; Wessel, A.W.; Case, J.B.; et al. A Single-Dose Intranasal Chad Vaccine Protects Upper and Lower Respiratory Tracts against SARS-CoV-2. Cell 2020, 183, 169–184.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.C.; Li, Y.H.; Guan, X.H.; Hou, L.H.; Wang, W.J.; Li, J.X.; Wu, S.P.; Wang, B.S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; et al. Safety, Tolerability, and Immunogenicity of a Recombinant Adenovirus Type-5 Vectored COVID-19 Vaccine: A Dose-Escalation, Open-Label, Non-Randomised, First-in-Human Trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseda, C.A.; Stauft, C.B.; Selvaraj, P.; Lien, C.Z.; Pedro, C.; Nunez, I.A.; Woerner, A.M.; Wang, T.T.; Weir, J.P. Mva Vector Expression of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Protection of Adult Syrian Hamsters against SARS-CoV-2 Challenge. npj Vaccines 2021, 6, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.C.; Wang, H.; Tian, L.L.; Pang, Z.H.; Yang, Q.K.; Huang, T.Q.; Fan, J.F.; Song, L.H.; Tong, Y.G.; Fan, H.H. COVID-19 Vaccine Development: Milestones, Lessons and Prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosatte, R. Evolution of Wildlife Rabies Control Tactics. Adv. Virus Res. 2011, 79, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Volz, A.; Sutterand, G. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara: History, Value in Basic Research, and Current Perspectives for Vaccine Development. Adv. Virus Res. 2017, 97, 187–243. [Google Scholar]

- Zaeck, L.M.; Lamers, M.M.; Verstrepen, B.E.; Bestebroer, T.M.; van Royen, M.E.; Gotz, H.; Shamier, M.C.; van Leeuwen, L.P.M.; Schmitz, K.S.; Alblas, K.; et al. Low Levels of Monkeypox Virus-Neutralizing Antibodies after Mva-Bn Vaccination in Healthy Individuals. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, G.; Moss, B. Nonreplicating Vaccinia Vector Efficiently Expresses Recombinant Genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 10847–10851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.L.; Benfield, C.T.O.; Maluquer de Motes, C.; Mazzon, M.; Ember, S.W.J.; Ferguson, B.J.; Sumner, R.P. Vaccinia Virus Immune Evasion: Mechanisms, Virulence and Immunogenicity. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 2367–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drexler, I.; Antunes, E.; Schmitz, M.; Wölfel, T.; Huber, C.; Erfle, V.; Rieber, P.; Theobald, M.; Sutter, G. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara for Delivery of Human Tyrosinase as Melanoma-Associated Antigen: Induction of Tyrosinase- and Melanoma-Specific Human Leukocyte Antigen a*0201-Restricted Cytotoxic T Cells in Vitro and Vivo. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 4955–4963. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosales, C.; Graham, V.V.; Rosas, G.A.; Merchant, H.; Rosales, R. A Recombinant Vaccinia Virus Containing the Papilloma E2 Protein Promotes Tumor Regression by Stimulating Macrophage Antibody-Dependent Cytotoxicity. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2000, 49, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, H.; Roberts, A.; Vogel, L.; Bukreyev, A.; Collins, P.L.; Murphy, B.R.; Subbarao, K.; Moss, B. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein Expressed by Attenuated Vaccinia Virus Protectively Immunizes Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6641–6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreijtz, J.H.; Suezer, Y.; van Amerongen, G.; de Mutsert, G.; Schnierle, B.S.; Wood, J.M.; Kuiken, T.; Fouchier, R.A.; Lower, J.; Osterhaus, A.D.; et al. Recombinant Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara-Based Vaccine Induces Protective Immunity in Mice against Infection with Influenza Virus H5n1. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 195, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreijtz, J.H.; Goeijenbier, M.; Moesker, F.M.; van den Dries, L.; Goeijenbier, S.; De Gruyter, H.L.; Lehmann, M.H.; de Mutsert, G.; van de Vijver, D.A.; Volz, A.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Modified-Vaccinia-Virus-Ankara-Based Influenza a H5n1 Vaccine: A Randomised, Double-Blind Phase 1/2a Clinical Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, M. Attenuated Poxvirus Vectors Mva and Nyvac as Promising Vaccine Candidates against Hiv/Aids. Human Vaccines 2009, 5, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verreck, F.A.W.; Vervenne, R.A.W.; Kondova, I.; van Kralingen, K.W.; Remarque, E.J.; Braskamp, G.; van der Werff, N.M.; Kersbergen, A.; Ottenhoff, T.H.M.; Heidt, P.J.; et al. Mva.85a Boosting of Bcg and an Attenuated, Phop Deficient M. Tuberculosis Vaccine Both Show Protective Efficacy against Tuberculosis in Rhesus Macaques. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Arriaza, J.; Arnáez, P.; Gómez, C.E.; Sorzano, C.O.S.; Esteban, M. Improving Adaptive and Memory Immune Responses of an Hiv/Aids Vaccine Candidate Mva-B by Deletion of Vaccinia Virus Genes (C6l and K7r) Blocking Interferon Signaling Pathways. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.; Fux, R.; Provacia, L.B.; Volz, A.; Eickmann, M.; Becker, S.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Haagmans, B.L.; Sutter, G. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein Delivered by Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Efficiently Induces Virus-Neutralizing Antibodies. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 11950–11954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlin, R.; Nugeyre, M.T.; Tchitchek, N.; Parenti, M.; Hocini, H.; Benjelloun, F.; Cannou, C.; Dereuddre-Bosquet, N.; Levy, Y.; Barré-Sinoussi, F.; et al. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Vector Induces Specific Cellular and Humoral Responses in the Female Reproductive Tract, the Main Hiv Portal of Entry. J. Immunol. 2017, 199, 1923–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, R.O.; Silk, S.E.; Elias, S.C.; Milne, K.H.; Rawlinson, T.A.; Llewellyn, D.; Shakri, A.R.; Jin, J.; Labbe, G.M.; Edwards, N.J.; et al. Human Vaccination against Plasmodium Vivax Duffy-Binding Protein Induces Strain-Transcending Antibodies. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e93683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T.; Dahlke, C.; Fathi, A.; Kupke, A.; Krahling, V.; Okba, N.M.A.; Halwe, S.; Rohde, C.; Eickmann, M.; Volz, A.; et al. Safety and Immunogenicity of a Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Vector Vaccine Candidate for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome: An Open-Label, Phase 1 Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.M.; Barrett, J.R.; Themistocleous, Y.; Rawlinson, T.A.; Diouf, A.; Martinez, F.J.; Nielsen, C.M.; Lias, A.M.; King, L.D.W.; Edwards, N.J.; et al. Vaccination with Plasmodium Vivax Duffy-Binding Protein Inhibits Parasite Growth During Controlled Human Malaria Infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eadf1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.L.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Schaub, J.M.; DiVenere, A.M.; Kuo, H.C.; Javanmardi, K.; Le, K.C.; Wrapp, D.; Lee, A.G.; Liu, Y.T.; et al. Structure-Based Design of Prefusion-Stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spikes. Science 2020, 369, 1501–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Arriaza, J.; Garaigorta, U.; Perez, P.; Lazaro-Frias, A.; Zamora, C.; Gastaminza, P.; Del Fresno, C.; Casasnovas, J.M.; Sorzano, C.O.S.; Sancho, D.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Candidates Based on Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Expressing the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Induce Robust T- and B-Cell Immune Responses and Full Efficacy in Mice. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e02260-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Americo, J.L.; Cotter, C.A.; Earl, P.L.; Erez, N.; Peng, C.; Moss, B. One or Two Injections of Mva-Vectored Vaccine Shields Hace2 Transgenic Mice from SARS-CoV-2 Upper and Lower Respiratory Tract Infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2026785118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routhu, N.K.; Cheedarla, N.; Gangadhara, S.; Bollimpelli, V.S.; Boddapati, A.K.; Shiferaw, A.; Rahman, S.A.; Sahoo, A.; Edara, V.V.; Lai, L.; et al. A Modified Vaccinia Ankara Vector-Based Vaccine Protects Macaques from SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Immune Pathology, and Dysfunction in the Lungs. Immunity 2021, 54, 542–556.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaro-Frias, A.; Perez, P.; Zamora, C.; Sanchez-Cordon, P.J.; Guzman, M.; Luczkowiak, J.; Delgado, R.; Casasnovas, J.M.; Esteban, M.; Garcia-Arriaza, J. Full Efficacy and Long-Term Immunogenicity Induced by the SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Candidate Mva-Cov2-S in Mice. npj Vaccines 2022, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.; Edwards, R.J.; Mansouri, K.; Janowska, K.; Stalls, V.; Gobeil, S.M.C.; Kopp, M.; Li, D.P.; Parks, R.; Hsu, A.L.; et al. Controlling the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.S.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.L.; Abiona, O.; Graham, B.S.; McLellan, J.S. Cryo-Em Structure of the 2019-Ncov Spike in the Prefusion Conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Americo, J.L.; Cotter, C.A.; Earl, P.L.; Liu, R.; Moss, B. Intranasal Inoculation of an Mva-Based Vaccine Induces Iga and Protects the Respiratory Tract of Hace2 Mice from SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2202069119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiuppesi, F.; Nguyen, V.H.; Park, Y.; Contreras, H.; Karpinski, V.; Faircloth, K.; Nguyen, J.; Kha, M.; Johnson, D.; Martinez, J.; et al. Synthetic Multiantigen Mva Vaccine Coh04s1 Protects against SARS-CoV-2 in Syrian Hamsters and Non-Human Primates. npj Vaccines 2022, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routhu, N.K.; Gangadhara, S.; Lai, L.; Davis-Gardner, M.E.; Floyd, K.; Shiferaw, A.; Bartsch, Y.C.; Fischinger, S.; Khoury, G.; Rahman, S.A.; et al. A Modified Vaccinia Ankara Vaccine Expressing Spike and Nucleocapsid Protects Rhesus Macaques against SARS-CoV-2 Delta Infection. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabo0226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, L.; Weskamm, L.M.; Fathi, A.; Kono, M.; Heidepriem, J.; Krahling, V.; Mellinghoff, S.C.; Ly, M.L.; Friedrich, M.; Hardtke, S.; et al. Mva-Based Vaccine Candidates Encoding the Native or Prefusion-Stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spike Reveal Differential Immunogenicity in Humans. npj Vaccines 2024, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, H.; Xiao, S.; Wang, J.M.; Wang, X.J.; Ge, J.Y.; Zhong, G.X.; Wen, Z.Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.L.; Wang, H.; et al. Rabies Virus-Based Oral and Inactivated Vaccines Protect Minks against SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Transmission. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 1198–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela Ramirez, J.E.; Sharpe, L.A.; Peppas, N.A. Current State and Challenges in Developing Oral Vaccines. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 114, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryawanshi, R.K.; Chen, I.P.; Ma, T.; Syed, A.M.; Brazer, N.; Saldhi, P.; Simoneau, C.R.; Ciling, A.; Khalid, M.M.; Sreekumar, B.; et al. Limited Cross-Variant Immunity from SARS-CoV-2 Omicron without Vaccination. Nature 2022, 607, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, L.; Huo, H.; Wang, Y.; Shuai, L.; Zhong, G.; Wen, Z.; Peng, L.; Ge, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; et al. Oral Administration of MVA-Vectored Vaccines Induces Robust, Long-Lasting Neutralizing Antibody Responses and Provides Complete Protection Against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice, Minks, and Cats. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121207

Feng L, Huo H, Wang Y, Shuai L, Zhong G, Wen Z, Peng L, Ge J, Wang J, Wang C, et al. Oral Administration of MVA-Vectored Vaccines Induces Robust, Long-Lasting Neutralizing Antibody Responses and Provides Complete Protection Against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice, Minks, and Cats. Vaccines. 2025; 13(12):1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121207

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Linya, Hong Huo, Yunlei Wang, Lei Shuai, Gongxun Zhong, Zhiyuan Wen, Liyan Peng, Jinying Ge, Jinliang Wang, Chong Wang, and et al. 2025. "Oral Administration of MVA-Vectored Vaccines Induces Robust, Long-Lasting Neutralizing Antibody Responses and Provides Complete Protection Against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice, Minks, and Cats" Vaccines 13, no. 12: 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121207

APA StyleFeng, L., Huo, H., Wang, Y., Shuai, L., Zhong, G., Wen, Z., Peng, L., Ge, J., Wang, J., Wang, C., Chen, W., He, X., Wang, X., & Bu, Z. (2025). Oral Administration of MVA-Vectored Vaccines Induces Robust, Long-Lasting Neutralizing Antibody Responses and Provides Complete Protection Against SARS-CoV-2 in Mice, Minks, and Cats. Vaccines, 13(12), 1207. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13121207