Correlation of HPV Status with Colposcopy and Cervical Biopsy Results Among Non-Vaccinated Women: Findings from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Subjects

- n—sample size,

- Z—coefficient depending on the confidence level chosen by the researcher,

- p—proportion of respondents with the presence of the studied characteristic,

- q = 1 − p—the proportion of respondents who do not have the studied characteristic,

- ∆—maximum sampling error.

2.2. Human Papillomavirus Testing and Liquid-Based Cytology

2.3. Colposcopy and Colposcopy-Guided Biopsy

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Consideration

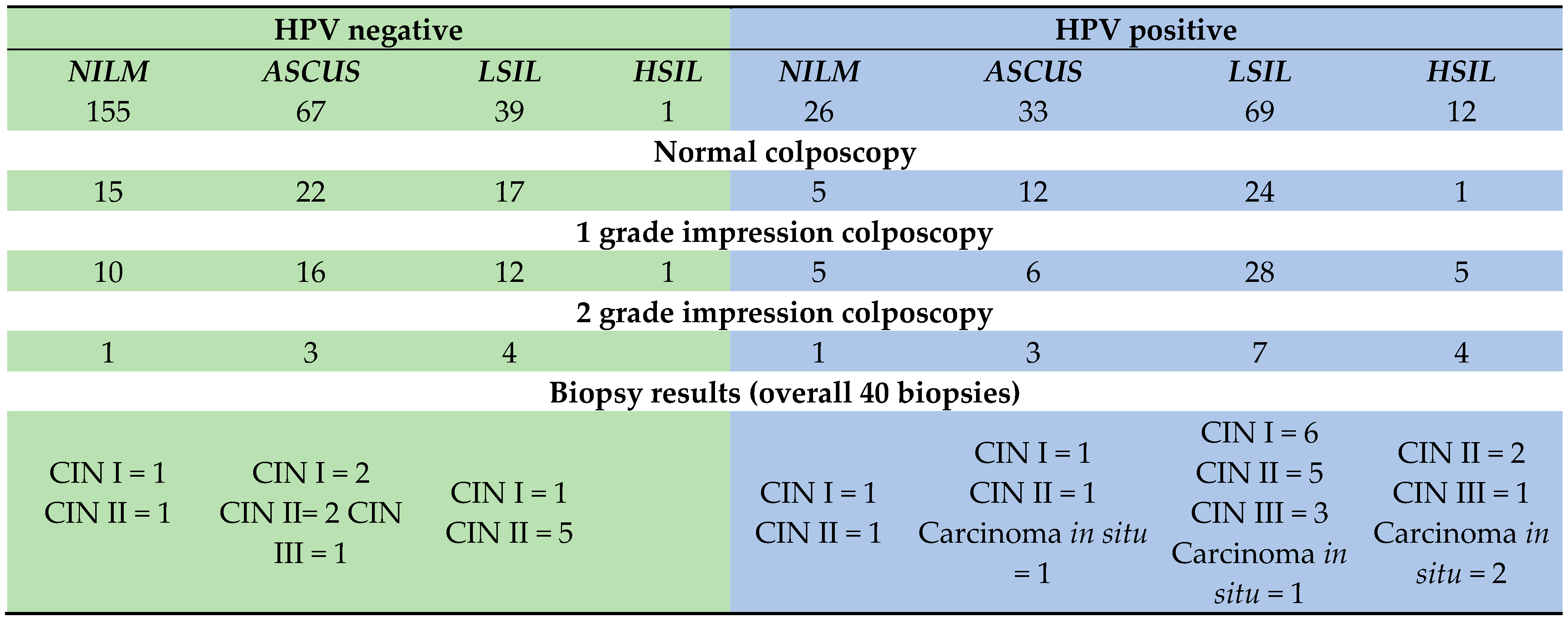

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Description of Study Subjects

3.2. Human Papillomavirus Status of Study Subjects

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Implementation of co-testing (cervical cytology and HPV genotyping) as a cervical cancer screening;

- Improve cervical cancer screening coverage and participation with community education, mobile screening teams, and electronic reminders.

- Improve laboratory quality assurance through standardized training, external audit, and laboratory accreditation;

- Integrate screening and vaccination registries for patient tracking;

- Increase public acceptance of HPV vaccination by implementing consistent nationwide information/communication interventions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2023 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific all-cause mortality and life expectancy estimates for 204 countries and territories and 660 subnational locations, 1950–2023: A demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1731–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2023 Cancer Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of cancer, 1990–2023, with forecasts to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1565–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. GLOBACAN. Cancer Tomorrow. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/en/dataviz/isotype?types=0&single_unit=5000&populations=900&group_populations=0&multiple_populations=0&years=2025&cancers=23 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Human Papillomavirus and Related Cancers, Fact Sheet: Kazakhstan; IARC/ICO Information Centre on HPV and Cancer: Lyon, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhetpisbayeva, I.; Rommel, A.; Kassymbekova, F.; Semenova, Y.; Sarmuldayeva, S.; Giniyat, A.; Tanatarova, G.; Dyussupova, A.; Faizova, R.; Rakhmetova, V.; et al. Cervical cancer trend in the Republic of Kazakhstan and attitudes towards cervical cancer screening in urban and rural areas. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Igissinov, N.; Igissinova, G.; Telmanova, Z.; Bilyalova, Z.; Kulmirzayeva, D.; Kozhakhmetova, Z.; Urazova, S.; Turebayev, D.; Nurtazinova, G.; Omarbekov, A.; et al. New Trends of Cervical Cancer Incidence in Kazakhstan. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shamsutdinova, A.; Kulkayeva, G.; Karashutova, Z.; Tanabayev, B.; Tanabayeva, S.; Ibrayeva, A.; Fakhradiyev, I. Analysis of the Effectiveness and Coverage of Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Screening Programs in Kazakhstan for the Period 2021–2023: Regional Disparities and Coverage Dynamics. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2024, 25, 4371–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). CanScreen5: Country Fact Sheet, Kazakhstan; IARC: Lyon, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe. Kazakhstan Launches National HPV Vaccination Programme; WHO Europe News: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Aimagambetova, G.; Chan, C.K.; Ukybassova, T.; Imankulova, B.; Balykov, A.; Kongrtay, K.; Azizan, A. Cervical cancer screening and prevention in Kazakhstan and Central Asia. J. Med. Screen. 2021, 28, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbyn, M.; Smith, S.B.; Temin, S.; Sultana, F.; Castle, P. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching under-screened women by using HPV testing on self samples: Updated meta-analyses. BMJ 2022, 376, e068532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassymbekova, F.; Kadirova, A.; Sarsenbayeva, G. Developing HPV vaccination communication strategies in Kazakhstan: Lessons learned from the 2013 pilot. Vaccine 2024, 42, 780–788. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Kazakhstan’s Roadmap to Cervical Cancer Elimination; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Babi, A.; Issa, T.; Issanov, A.; Akilzhanova, A.; Nurgaliyeva, K.; Abugalieva, Z.; Ukybassova, T.; Daribay, Z.; Khan, S.A.; Chan, C.K.; et al. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection among Kazakhstani women attending gynecological outpatient clinics. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 109, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aimagambetova, G.; Babi, A.; Issanov, A.; Akhanova, S.; Udalova, N.; Koktova, S.; Balykov, A.; Sattarkyzy, Z.; Abakasheva, Z.; Azizan, A.; et al. The Distribution and Prevalence of High-Risk HPV Genotypes Other than HPV-16 and HPV-18 among Women Attending Gynecologists’ Offices in Kazakhstan. Biology 2021, 10, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Drolet, M.; Bénard, É.; Pérez, N.; Brisson, M.; HPV Vaccination Impact Study Group. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kohale, M.G.; Dhobale, A.V.; Hatgoankar, K.; Bahadure, S.; Salgar, A.H.; Bandre, G.R. Comparison of Colposcopy and Histopathology in Abnormal Cervix. Cureus 2024, 16, e54274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadoran, E.; Rahmani, B.; Nazari, E.; Hosseinnezhad, A.; Samieerad, F. Comparison of Diagnostic Methods in Patients with Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion in Women Infected with Multiple High-Risk Human Papillomaviruses. Iran. J. Pathol. 2025, 20, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aimagambetova, G.; Babi, A.; Issa, T.; Issanov, A. What Factors are Associated with Attitudes Towards HPV Vaccination Among Kazakhstani Women? Exploratory Analysis of Cross-Sectional Survey Data. Vaccines 2022, 10, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Babi, A.; Issa, T.; Issanov, A.; Akhanova, S.; Udalova, N.; Koktova, S.; Balykov, A.; Sattarkyzy, Z.; Imankulova, B.; Kamzayeva, N.; et al. Knowledge and attitudes of mothers toward HPV vaccination: A cross-sectional study in Kazakhstan. Women’s Health 2023, 19, 17455057231172355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imankulova, B.; Babi, A.; Issa, T.; Zhumakanova, Z.; Knaub, L.; Yerzhankyzy, A.; Aimagambetova, G. Prevalence of Precancerous Cervical Lesions Among Nonvaccinated Kazakhstani Women: The National Tertiary Care Hospital Screening Data (2018). Healthcare 2023, 11, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.B.; Dunton, C.J. Colposcopy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564514/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ronco, G.; Dillner, J.; Elfström, K.M.; Tunesi, S.; Snijders, P.J.; Arbyn, M.; Kitchener, H.; Segnan, N.; Gilham, C.; Giorgi-Rossi, P. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: Follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014, 383, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Serrano, B.; Mena, M.; Collado, J.J.; Gómez, D.; Muñoz, J.; Bosch, F.X.; de Sanjosé, S. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in the World. Summary Report 10 March 2023. Available online: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/XWX.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Clifford, G.M.; Tully, S.; Franceschi, S. Carcinogenicity of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Types in HIV-Positive Women: A Meta-Analysis from HPV Infection to Cervical Cancer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekalegn, Y.; Sahiledengle, B.; Woldeyohannes, D.; Atlaw, D.; Degno, S.; Desta, F.; Bekele, K.; Aseffa, T.; Gezahegn, H.; Kene, C. High parity is associated with increased risk of cervical cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Women’s Health 2022, 18, 17455065221075904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombe Kombe, A.J.; Li, B.; Zahid, A.; Mengist, H.M.; Bounda, G.A.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, T. Epidemiology and Burden of Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases, Molecular Pathogenesis, and Vaccine Evaluation. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 552028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, F.X.; Broker, T.R.; Forman, D.; Moscicki, A.B.; Gillison, M.L.; Doorbar, J.; Stern, P.L.; Stanley, M.; Arbyn, M.; Poljak, M.; et al. Comprehensive control of human papillomavirus infections and related diseases. Vaccine 2013, 31 (Suppl. 7), H1–H31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, P.; Howell-Jones, R.; Li, N.; Bruni, L.; de Sanjosé, S.; Franceschi, S.; Clifford, G.M. Human papillomavirus types in 115,789 HPV-positive women: A meta-analysis from cervical infection to cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auvray, C.; Douvier, S.; Caritey, O.; Bour, J.B.; Manoha, C. Relative distribution of HPV genotypes in histological cervical samples and associated grade lesion in a women population over the last 16 years in Burgundy, France. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1224400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, V.; Hörner, L.; Nkurunziza, T.; Rank, S.; Tanaka, L.F.; Klug, S.J. Global prevalence of cervical human papillomavirus in women aged 50 years and older with normal cytology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Microbe 2025, 6, 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babi, A.; Issa, T.; Gusmanov, A.; Akilzhanova, A.; Issanov, A.; Makhmetova, N.; Marat, A.; Iztleuov, Y.; Aimagambetova, G. Prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus infection and genotype distribution among Kazakhstani women with abnormal cervical cytology. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2304649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Aluloski, I.; Aluloski, D.; Dizdarevic Maksumic, A.; Ghayrat Umarzoda, S.; Gutu, V.; Ilmammedova, M.; Janashia, A.; Kocinaj-Berisha, M.; Matylevich, O.; et al. Update on HPV Vaccination Policies and Practices in 17 Eastern European and Central Asian Countries and Territories. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 4227–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Warsi, S.K.; Nielsen, S.M.; Franklin, B.A.K.; Abdullaev, S.; Ruzmetova, D.; Raimjanov, R.; Nagiyeva, K.; Safaeva, K. Formative Research on HPV Vaccine Acceptance Among Health Workers, Teachers, Parents, and Social Influencers in Uzbekistan. Vaccines 2023, 11, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharipova, I.P.; Mirzaev, U.K.; Kasimova, R.I.; Yoshinaga, Y.; Shrapov, S.M.; Suyarkulova, D.T.; Musabaev, E.I. Optimizing Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Screening: Urine Sample Analysis and Associated Factors in Uzbekistan. Cureus 2024, 16, e69816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Simion, L.; Rotaru, V.; Cirimbei, C.; Gales, L.; Stefan, D.C.; Ionescu, S.O.; Luca, D.; Doran, H.; Chitoran, E. Inequities in Screening and HPV Vaccination Programs and Their Impact on Cervical Cancer Statistics in Romania. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koliopoulos, G.; Nyaga, V.N.; Santesso, N.; Bryant, A.; Martin-Hirsch, P.P.; Mustafa, R.A.; Schünemann, H.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Arbyn, M. Cytology versus HPV testing for cervical cancer screening in the general population. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 8, CD008587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleş, L.; Radosa, J.C.; Sima, R.M.; Chicea, R.; Olaru, O.G.; Poenaru, M.O. The Accuracy of Cytology, Colposcopy and Pathology in Evaluating Precancerous Cervical Lesions. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wentzensen, N.; Massad, L.S.; Mayeaux, E.J., Jr.; Khan, M.J.; Waxman, A.G.; Einstein, M.H.; Conageski, C.; Schiffman, M.H.; Gold, M.A.; Apgar, B.S.; et al. Evidence-Based Consensus Recommendations for Colposcopy Practice for Cervical Cancer Prevention in the United States. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2017, 21, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentzensen, N.; Walker, J.L.; Gold, M.A.; Smith, K.M.; Zuna, R.E.; Mathews, C.; Dunn, S.T.; Zhang, R.; Moxley, K.; Bishop, E.; et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Variable | Statistics | HPV Negative | HPV Positive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean ± SD | 35.25 ± 6.18 | 33.17 ± 6.60 |

| Median [Q1–Q3] | 34.96 [31.60–40.00] | 33.86 [27.92–37.48] | |

| Min–Max | 19.93–45.88 | 19.90–46.03 | |

| Statistic (p) | t = 3.13 | p = 0.0019 | |

| Ethnicity | Kazakh | 236 (91.8%) | 125 (89.9%) |

| Russian | 12 (4.7%) | 8 (5.8%) | |

| Others | 9 (3.5%) | 6 (4.3%) | |

| Statistic (p) | Chi-square: 11.09 | p = 0.4354 | |

| Education | Incomplete secondary | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Secondary professional | 42 (16.3%) | 17 (12.2%) | |

| Bachelor | 178 (69.3%) | 98 (70.5%) | |

| Masters | 32 (12.5%) | 21 (15.1%) | |

| PhD | 3 (1.2%) | 2 (1.4%) | |

| Statistic (p) | Chi-square: 1.58 | p = 0.8130 | |

| Marital status | Single | 48 (18.7%) | 43 (30.9%) |

| Married | 184 (71.6%) | 77 (55.4%) | |

| Divorced | 22 (8.6%) | 18 (12.9%) | |

| Widow | 3 (1.2%) | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Statistic (p) | Chi-square: 11.39 | p = 0.0098 | |

| BMI | Mean ± SD | 23.85 ± 4.62 | 23.36 ± 4.56 |

| Median [Q1–Q3] | 23.14 [20.57–26.35] | 22.31 [20.26–25.56] | |

| Min–Max | 15.78–43.26 | 14.88–42.80 | |

| Statistic (p) | t = 1.03 | p = 0.3037 | |

| Number of sexual partners | Mean ± SD | 1.57 ± 1.79 | 2.18 ± 5.42 |

| Median [Q1–Q3] | 1.00 [1.00–1.00] | 1.00 [1.00–2.00] | |

| Min–Max | 0.00–20.00 | 0.00–60.00 | |

| Statistic (p) | t = −1.65 | p = 0.0991 | |

| Number of pregnancies | Mean ± SD | 2.38 ± 1.91 | 1.51 ± 1.60 |

| Median [Q1–Q3] | 2.00 [1.00–4.00] | 1.00 [0.00–2.00] | |

| Min–Max | 0.00–8.00 | 0.00–9.00 | |

| Statistic (p) | U = 22,720.00 | p = 0.0000 | |

| Number of deliveries | Mean ± SD | 1.74 ± 1.39 | 1.20 ± 1.26 |

| Median [Q1–Q3] | 2.00 [0.00–3.00] | 1.00 [0.00–2.00] | |

| Min–Max | 0.00–5.00 | 0.00–5.00 | |

| Statistic (p) | t = 3.81 | p = 0.0002 | |

| Number of abortions | Mean ± SD | 0.36 ± 0.74 | 0.13 ± 0.43 |

| Median [Q1–Q3] | 0.00 [0.00–0.00] | 0.00 [0.00–0.00] | |

| Min–Max | 0.00–4.00 | 0.00–3.00 | |

| Statistic (p) | U = 20,258.00 | p = 0.0011 | |

| Abortions | 0 | 198 (77.0%) | 125 (89.9%) |

| 1 | 59 (23.0%) | 14 (10.1%) | |

| Statistic (p) | Chi-square: 9.12 | p = 0.0025 | |

| Barrier contraception | 0 | 182 (70.8%) | 82 (59.0%) |

| 1 | 75 (29.2%) | 57 (41.0%) | |

| Statistic (p) | Chi-square: 5.16 | p = 0.0232 | |

| Hormonal contraception | 0 | 249 (96.9%) | 136 (97.8%) |

| 1 | 8 (3.1%) | 3 (2.2%) | |

| Statistic (p) | Fisher: 0.69 | p = 0.7536 | |

| Any contraception | 0 | 174 (67.7%) | 79 (56.8%) |

| 1 | 83 (32.3%) | 60 (43.2%) | |

| Statistic (p) | Chi-square: 4.16 | p = 0.0414 | |

| STI negative | 53 (20.6%) | 35 (25.2%) | |

| STI status | STI positive | 204 (79.4%) | 104 (74.8%) |

| Statistic (p) | Chi-square: 0.84 | p = 0.3604 |

| Variable | Statistic | Overall | Normal Colposcopy | 1 Grade Impression Colposcopy | 2 Grade Impression Colposcopy | Chi2 Statistic | Chi2 p-Value (FDR-BH) | Cramér’s V | CATT p-Value (FDR-BH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV-16 | Negative | 162 (81.8%) | 87 (90.6%) | 65 (80.2%) | 10 (47.6%) | 21.65 | 0.000259 | 0.331 | 0.000226 |

| Positive | 36 (18.2%) | 9 (9.4%) | 16 (19.8%) | 11 (52.4%) | |||||

| Group 0 vs. 1 | OR = 0.42 [0.17–1.01], p (Holm) = 0.0541 | ||||||||

| Group 0 vs. 2 | OR = 0.09 [0.03–0.28], p (Holm) = 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Group 1 vs. 2 | OR = 0.22 [0.08–0.62], p (Holm) = 0.0095 | ||||||||

| HPV-18 | Negative | 185 (93.4%) | 90 (93.8%) | 75 (92.6%) | 20 (95.2%) | 0.22 | 0.969078 | 0.033 | 0.974141 |

| Positive | 13 (6.6%) | 6 (6.2%) | 6 (7.4%) | 1 (4.8%) | |||||

| HPV-31 | Negative | 189 (95.5%) | 92 (95.8%) | 77 (95.1%) | 20 (95.2%) | 0.06 | 0.969078 | 0.018 | 0.974141 |

| Positive | 9 (4.5%) | 4 (4.2%) | 4 (4.9%) | 1 (4.8%) | |||||

| HPV-33 | Negative | 182 (91.9%) | 89 (92.7%) | 72 (88.9%) | 21 (100.0%) | 2.93 | 0.740104 | 0.122 | 0.974141 |

| Positive | 16 (8.1%) | 7 (7.3%) | 9 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| HPV-35 | Negative | 193 (97.5%) | 93 (96.9%) | 81 (100.0%) | 19 (90.5%) | 6.42 | 0.262658 | 0.180 | 0.974141 |

| Positive | 5 (2.5%) | 3 (3.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (9.5%) | |||||

| Group 0 vs. 1 | OR = 6.10 [0.31–119.90], p (Holm) = 0.4377 | ||||||||

| Group 0 vs. 2 | OR = 0.31 [0.05–1.96], p (Holm) = 0.4377 | ||||||||

| Group 1 vs. 2 | OR = 0.05 [0.00–1.04], p (Holm) = 0.1223 | ||||||||

| HPV-39 | Negative | 187 (94.4%) | 90 (93.8%) | 77 (95.1%) | 20 (95.2%) | 0.17 | 0.969078 | 0.029 | 0.974141 |

| Positive | 11 (5.6%) | 6 (6.2%) | 4 (4.9%) | 1 (4.8%) | |||||

| HPV-45 | Negative | 187 (94.4%) | 92 (95.8%) | 76 (93.8%) | 19 (90.5%) | 1.04 | 0.857886 | 0.073 | 0.925942 |

| Positive | 11 (5.6%) | 4 (4.2%) | 5 (6.2%) | 2 (9.5%) | |||||

| HPV-51 | Negative | 189 (95.5%) | 93 (96.9%) | 77 (95.1%) | 19 (90.5%) | 1.67 | 0.803843 | 0.092 | 0.925942 |

| Positive | 9 (4.5%) | 3 (3.1%) | 4 (4.9%) | 2 (9.5%) | |||||

| HPV-52 | Negative | 181 (91.4%) | 89 (92.7%) | 74 (91.4%) | 18 (85.7%) | 1.07 | 0.857886 | 0.074 | 0.925942 |

| Positive | 17 (8.6%) | 7 (7.3%) | 7 (8.6%) | 3 (14.3%) | |||||

| HPV-56 | Negative | 187 (94.4%) | 91 (94.8%) | 76 (93.8%) | 20 (95.2%) | 0.11 | 0.969078 | 0.023 | 0.974141 |

| Positive | 11 (5.6%) | 5 (5.2%) | 5 (6.2%) | 1 (4.8%) | |||||

| HPV-59 | Negative | 183 (92.4%) | 89 (92.7%) | 73 (90.1%) | 21 (100.0%) | 2.34 | 0.740104 | 0.109 | 0.974141 |

| Positive | 15 (7.6%) | 7 (7.3%) | 8 (9.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| HPV-58 | Negative | 190 (96.0%) | 92 (95.8%) | 79 (97.5%) | 19 (90.5%) | 2.15 | 0.740104 | 0.104 | 0.974141 |

| Positive | 8 (4.0%) | 4 (4.2%) | 2 (2.5%) | 2 (9.5%) | |||||

| HPV status | Negative | 98 (49.5%) | 53 (55.2%) | 38 (46.9%) | 7 (33.3%) | 3.66 | 0.693801 | 0.136 | 0.388964 |

| Positive | 100 (50.5%) | 43 (44.8%) | 43 (53.1%) | 14 (66.7%) | |||||

| Variable | Status | Overall | CIN I | CIN II | CIN III | Carcinoma In Situ | Fisher’s Exact p-Value (MC) | Fisher’s Exact p-Value (MC) (FDR-BH) | Cramér’s V | CATT p-Value (FDR-BH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV-16 | Negative | 24 (63.2%) | 10 (83.3%) | 12 (70.6%) | 1 (20.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 0.031197 | 0.181982 | 0.487 | 0.078658 |

| Positive | 14 (36.8%) | 2 (16.7%) | 5 (29.4%) | 4 (80.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | |||||

| CIN I vs. CIN II | OR = 0.48 [0.08–3.03], p (Holm) = 1.0000 | |||||||||

| CIN I vs. CIN III | OR = 0.05 [0.00–0.72], p (Holm) = 0.1658 | |||||||||

| CIN I vs. CIS | OR = 0.07 [0.00–1.02], p (Holm) = 0.3159 | |||||||||

| CIN II vs. CIN III | OR = 0.10 [0.01–1.18], p (Holm) = 0.4634 | |||||||||

| CIN II vs. CIS | OR = 0.14 [0.01–1.68], p (Holm) = 0.7584 | |||||||||

| CIN III vs. CIS | OR = 1.33 [0.06–31.12], p (Holm) = 1.0000 | |||||||||

| HPV-18 | Negative | 36 (94.7%) | 11 (91.7%) | 17 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0.208579142 | 0.625737426 | 0.347 | 0.836420 |

| Positive | 2 (5.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | |||||

| HPV-33 | Negative | 35 (92.1%) | 10 (83.3%) | 16 (94.1%) | 5 (100.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0.837216278 | 1 | 0.237 | 0.847951 |

| Positive | 3 (7.9%) | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| HPV-35 | Negative | 37 (97.4%) | 12 (100.0%) | 16 (94.1%) | 5 (100.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 1 | 1 | 0.183 | 0.847951 |

| Positive | 1 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| HPV-39 | Negative | 36 (94.7%) | 11 (91.7%) | 16 (94.1%) | 5 (100.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0.342365763 | 0.732526747 | 0.140 | 0.847951 |

| Positive | 2 (5.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| HPV-45 | Negative | 35 (92.1%) | 12 (100.0%) | 16 (94.1%) | 5 (100.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 0.04549545 | 0.181981802 | 0.545 | 0.118364 |

| Positive | 3 (7.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | |||||

| CIN I vs. CIN II | OR = 0.44 [0.02–11.74], p (Holm) = 1.0000 | |||||||||

| CIN I vs. CIS | OR = 0.04 [0.00–1.11], p (Holm) = 0.2500 | |||||||||

| CIN II vs. CIN III | OR = 1.00 [0.04–28.30], p (Holm) = 1.0000 | |||||||||

| CIN II vs. CIS | OR = 0.06 [0.00–1.04], p (Holm) = 0.3188 | |||||||||

| CIN III vs. CIS | OR = 0.09 [0.00–2.68], p (Holm) = 0.5000 | |||||||||

| HPV-51 | Negative | 35 (92.1%) | 11 (91.7%) | 16 (94.1%) | 5 (100.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0.620437956 | 0.930656934 | 0.237 | 0.836420 |

| Positive | 3 (7.9%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | |||||

| HPV-52 | Negative | 36 (94.7%) | 11 (91.7%) | 16 (94.1%) | 5 (100.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 1 | 1 | 0.140 | 0.847951 |

| Positive | 2 (5.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| HPV-56 | Negative | 36 (94.7%) | 10 (83.3%) | 17 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 0.366263374 | 0.732526747 | 0.347 | 0.847951 |

| Positive | 2 (5.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| HPV-59 | Negative | 36 (94.7%) | 11 (91.7%) | 16 (94.1%) | 5 (100.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | 1 | 1 | 0.140 | 0.847951 |

| Positive | 2 (5.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| HPV-58 | Negative | 36 (94.7%) | 12 (100.0%) | 17 (100.0%) | 5 (100.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 0.00879912 | 0.105589441 | 0.687 | 0.118364 |

| Positive | 2 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | |||||

| CIN I vs. CIS | OR = 0.04 [0.00–1.11], p (Holm) = 0.1000 | |||||||||

| CIN II vs. CIS | OR = 0.03 [0.00–0.78], p (Holm) = 0.0857 | |||||||||

| CIN III vs. CIS | OR = 0.09 [0.00–2.68], p (Holm) = 0.1667 | |||||||||

| HPV status | Negative | 13 (34.2%) | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (47.1%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.462653735 | 0.793120688 | 0.315 | 0.836420 |

| Positive | 25 (65.8%) | 8 (66.7%) | 9 (52.9%) | 4 (80.0%) | 4 (100.0%) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ukybassova, T.; Aimagambetova, G.; Kongrtay, K.; Kassymbek, K.; Terzic, M.; Makhambetova, S.; Galym, M.; Kamzayeva, N. Correlation of HPV Status with Colposcopy and Cervical Biopsy Results Among Non-Vaccinated Women: Findings from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kazakhstan. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111151

Ukybassova T, Aimagambetova G, Kongrtay K, Kassymbek K, Terzic M, Makhambetova S, Galym M, Kamzayeva N. Correlation of HPV Status with Colposcopy and Cervical Biopsy Results Among Non-Vaccinated Women: Findings from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kazakhstan. Vaccines. 2025; 13(11):1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111151

Chicago/Turabian StyleUkybassova, Talshyn, Gulzhanat Aimagambetova, Kuralay Kongrtay, Kuat Kassymbek, Milan Terzic, Sanimkul Makhambetova, Makhabbat Galym, and Nazira Kamzayeva. 2025. "Correlation of HPV Status with Colposcopy and Cervical Biopsy Results Among Non-Vaccinated Women: Findings from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kazakhstan" Vaccines 13, no. 11: 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111151

APA StyleUkybassova, T., Aimagambetova, G., Kongrtay, K., Kassymbek, K., Terzic, M., Makhambetova, S., Galym, M., & Kamzayeva, N. (2025). Correlation of HPV Status with Colposcopy and Cervical Biopsy Results Among Non-Vaccinated Women: Findings from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Kazakhstan. Vaccines, 13(11), 1151. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13111151