Redefining High-Risk and Mobile Population in Pakistan Polio Eradication Program; 2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

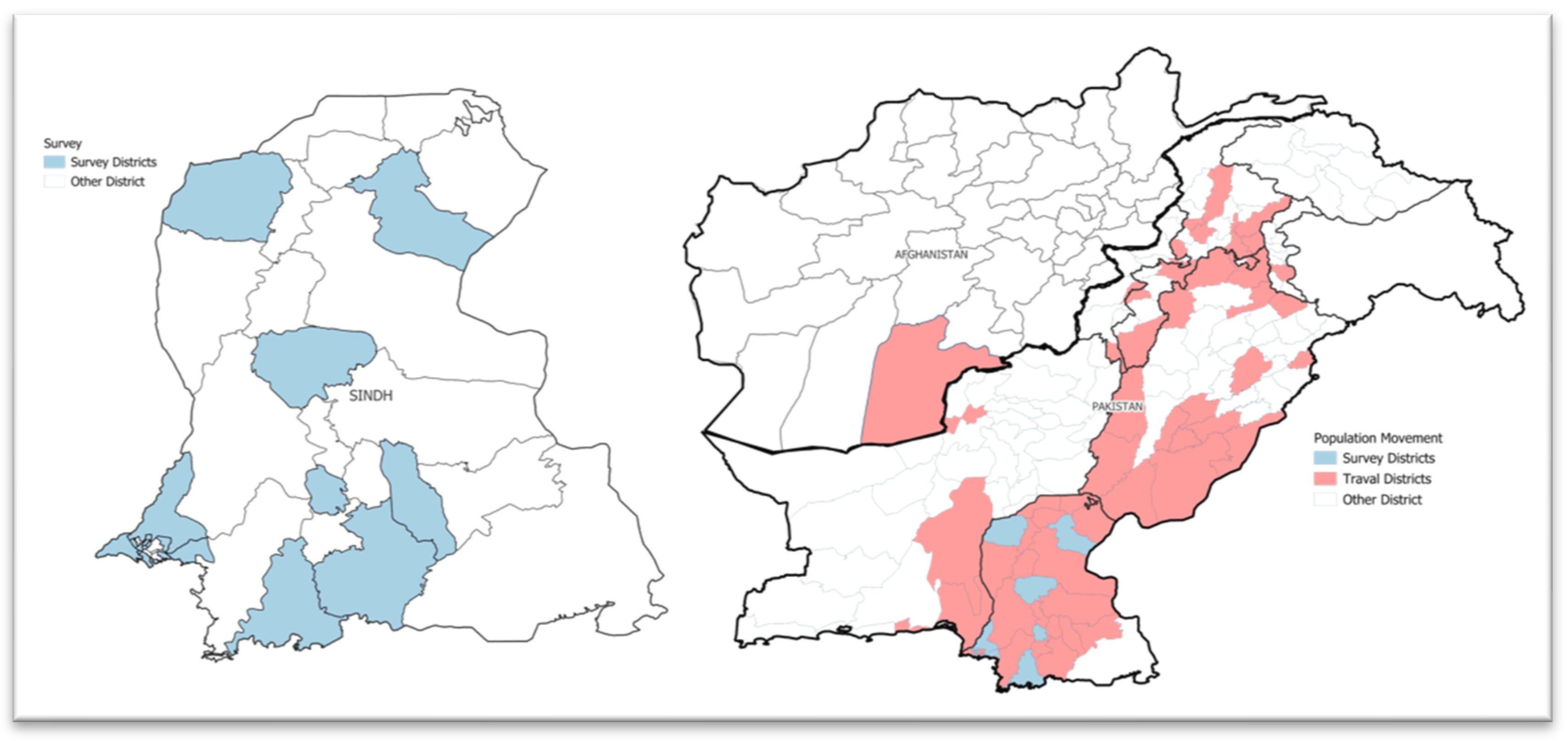

2.1. Study Design, Settings, and Population

2.2. Study Variables and Data Collection

2.3. Data Management and Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics in the Karachi Division

3.2. Participant Characteristics in Other Divisions of Sindh Province

3.3. Binary Analysis: Comparison Between Karachi Division and Other Divisions of Sindh

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Poliomyelitis. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/poliomyelitis (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Sodhar, I.A.; Hussaini, A.S.; Brown, M.J. Eradicating polio: A perspective from Pakistan. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2023, 28, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 69th World Health Assembly. Poliomyelitis: Report by the Secretariat. 2016. Available online: https://polioeradication.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/A69_25-en.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Owais, A.; Khowaja, A.R.; Ali, S.A.; Zaidi, A.K. Pakistan’s expanded programme on immunization: An overview in the context of polio eradication and strategies for improving coverage. Vaccine 2013, 31, 3313–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Immunization Schedule—Federal Directorate of Immunization, Pakistan. Available online: https://epi.gov.pk/immunization-schedule/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Ataullahjan, A.; Ahsan, H.; Soofi, S.; Habib, M.A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Eradicating polio in Pakistan: A systematic review of programs and policies. Expert. Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polio Eradication Organization Website. Available online: https://polioeradication.org/who-we-are/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Pakistan Polio Eradication Programme Vaccinating Pak-Afghan Border-Stepping Towards a Polio Free Region. Available online: https://www.endpolio.com.pk/media-room/field-stories/vaccinating-pak-afghan-border-stepping-towards-a-polio-free-region#:~:text=The%20Pakistan%20Polio%20Eradication%20Programme,the%20country%20through%20Kharlachi%20border (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Hovi, T.; Shulman, L.M.; Van Der Avoort, H.; Deshpande, J.; Roivainen, M.; De Gourville, E.M. Role of environmental poliovirus surveillance in global polio eradication and beyond. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 140, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Laboratories Division. Available online: https://www.nih.org.pk/national-health-laboratory (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- The Global Polio Laboratory Network. Available online: https://www.archive.polioeradication.org/polio-today/polio-now/surveillance-indicators/the-global-polio-laboratory-network-gpln/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- The Polio Challenge. The News International: Latest News Breaking, Pakistan News. Available online: https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/1228017-the-polio-challenge/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Hussain, I.; Umer, M.; Khan, A.; Sajid, M.; Ahmed, I.; Begum, K.; Iqbal, J.; Alam, M.M.; Safdar, R.M.; Baig, S.; et al. Exploring the path to polio eradication: Insights from consecutive seroprevalence surveys among Pakistani children. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1384410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodhar, I.A.; Mehraj, J.; Hussaini, A.S.; Aamir, M.; Mahsaud, J.; Ahmed, S.; Shaikh, A.A.; Zardari, A.A.; Rasool, S.; Chandio, S.A.; et al. Population Movement and Poliovirus Spread across Pakistan and Afghanistan in 2023. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtar, R.; Mahmood, N.; Alam, M.M.; Naeem, M.; Zaidi, S.S.; Sharif, S.; Khattak, Z.; Arshad, Y.; Khurshid, A.; Mujtaba, G.; et al. Genetic epidemiology reveals 3 chronic reservoir areas with recurrent population mobility challenging poliovirus eradication in Pakistan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, e58–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.M.; Sharif, S.; Shaukat, S.; Angez, M.; Khurshid, A.; Rehman, L.; Zaidi, S.S. Genomic surveillance elucidates persistent wild poliovirus transmission during 2013–2015 in major reservoir areas of Pakistan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molodecky, N.A.; Usman, A.; Javaid, A.; Wahdan, A.; Parker, E.P.; Ahmed, J.A.; Shah, N.; Agbor, J.; Mahamud, A.; Safdar, R.M. Quantifying movement patterns and vaccination status of high-risk mobile populations in Pakistan and Afghanistan to inform poliovirus risk and vaccination strategy. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2124–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaukat, S.; Angez, M.; Alam, M.M.; Sharif, S.; Khurshid, A.; Malik, F.; Rehman, L.; Zaidi, S.S. Molecular characterization and phylogenetic relationship of wild type 1 poliovirus strains circulating across Pakistan and Afghanistan bordering areas during 2010–2012. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, D.; Pons-Salort, M.; Shaw, A.G.; Grassly, N.C. The role of genetic sequencing and analysis in the polio eradication programme. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, veaa040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, S.S.; Zaidi, S.; Riaz, A.; Tahir, H.N.; Mazhar, L.A.; Memon, Z. Social determinants of low uptake of childhood vac-cination in high-risk squatter settlements in Karachi, Pakistan—A step towards addressing vaccine inequity in urban slums. Vaccine X 2024, 17, 100427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.; Mohammed, R.; Butt, E.; Butt, S.; Xiang, J. Why Have Immunization Efforts in Pakistan Failed to Achieve Global Standards of Vaccination Uptake and Infectious Disease Control? Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aga Khan University. Third Party Verification Immunization Coverage Survey (TPVICS). Survey Report June 2021. Available online: https://www.aku.edu/coe-wch/Documents/TPVICS%20Survey%20Report.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Paul, Y. Why has polio eradication program failed in India? Indian Pediatr. 2008, 45, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paul, Y. Role of genetic factors in polio eradication: New challenge for policy makers. Vaccine 2007, 25, 8365–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gushulak, B.D.; MacPherso, D.W. Population Mobility and Infectious Diseases: The Diminishing Impact of Classical Infectious Diseases and New Approaches for the 21st Century. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2000, 31, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Central | Keamari | Malir | South | West | Karachi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 636) | (N = 231) | (N = 240) | (N = 60) | (N = 225) | (N = 1392) | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 480 (75.5%) | 152 (65.8%) | 103 (42.9%) | 50 (83.3%) | 187 (83.1%) | 972 (69.9%) |

| Male | 156 (24.4%) | 79 (34.2%) | 137 (57.1%) | 10 (16.7%) | 38 (16.9%) | 420 (30.2%) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 33.364 (9.2543) | 34.872 (8.6133) | 34.963 (10.2877) | 35.317 (8.8825) | 34.576 (10.2688) | 34.170 (9.5103) |

| Language | ||||||

| Balochi | 18 (2.8%) | 16 (6.9%) | 5 (2.1%) | 19 (31.7%) | 23 (10.2%) | 81 (5.8%) |

| Pashto | 107 (16.8%) | 121 (52.4%) | 19 (7.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 89 (39.6%) | 336 (24.1%) |

| Punjabi | 68 (10.7%) | 13 (5.6%) | 64 (26.7%) | 4 (6.7%) | 6 (2.7%) | 155 (11.1%) |

| Sindhi | 61 (9.6%) | 11 (4.8%) | 49 (20.4%) | 5 (8.3%) | 4 (1.8%) | 130 (9.3%) |

| Siraiki | 96 (15.1%) | 6 (2.6%) | 15 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 118 (8.5%) |

| Urdu | 180 (28.3%) | 17 (7.4%) | 67 (27.9%) | 23 (38.3%) | 89 (39.6%) | 376 (27.0%) |

| Others | 106 (16.7%) | 47 (20.3%) | 21 (8.8%) | 9 (15.0%) | 13 (5.8%) | 196 (14.1%) |

| Number of children under five years of age (mean ± SD) | 1.602 (0.8734) | 1.632 (0.8840) | 1.533 (0.9545) | 1.617 (0.8456) | 1.622 (1.3108) | 1.599 (0.9706) |

| OPV vaccination in SIA status | ||||||

| No response | 5 (0.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | 5 (2.1%) | 1 (1.7%) | 3 (1.3%) | 15 (1.1%) |

| No | 27 (4.2%) | 9 (3.9%) | 10 (4.2%) | 3 (5.0%) | 18 (8.0%) | 67 (4.8%) |

| Yes | 604 (95.0%) | 221 (95.7%) | 225 (93.8%) | 56 (93.3%) | 204 (90.7%) | 1310 (94.1%) |

| RI status | ||||||

| No | 55 (8.6%) | 11 (4.8%) | 30 (12.5%) | 3 (5.0%) | 32 (14.2%) | 131 (9.4%) |

| Yes partial | 144 (22.6%) | 67 (29.0%) | 60 (25.0%) | 6 (10.0%) | 67 (29.8%) | 344 (24.7%) |

| Yes complete | 437 (68.7%) | 153 (66.2%) | 150 (62.5%) | 51 (85.0%) | 126 (56.0%) | 917 (65.9%) |

| Guest arrival | ||||||

| No | 147 (23.1%) | 66 (28.6%) | 56 (23.3%) | 16 (26.7%) | 49 (21.8%) | 334 (24.0%) |

| Yes | 489 (76.9%) | 165 (71.4%) | 184 (76.7%) | 44 (73.3%) | 176 (78.2%) | 1058 (75.9%) |

| Any Guest children vaccinated | ||||||

| No response | 224 (35.2%) | 27(11.7%) | 56 (23.3%) | 16 (26.7%) | 22 (9.8%) | 345 (24.8%) |

| No | 177 (27.8%) | 50 (21.6%) | 54 (22.5%) | 21 (35.0%) | 62 (27.6%) | 364 (26.1%) |

| Yes | 235 (36.9%) | 154 (66.7%) | 130 (54.2%) | 23 (38.3%) | 141 (62.7%) | 683 (49.1%) |

| Travel history | ||||||

| No | 346 (54.4%) | 91 (39.4%) | 120 (50.0%) | 39 (65.0%) | 110 (48.9%) | 706 (50.7%) |

| Yes | 290 (45.6%) | 140 (60.6%) | 120 (50.0%) | 21 (35.0%) | 115 (51.1%) | 686 (49.3%) |

| Purpose of travel | ||||||

| Business | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 5 (0.4%) |

| Education | 0 (0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Job | 12 (1.9%) | 8 (3.5%) | 28 (11.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.9%) | 50 (3.6%) |

| Family event | 82 (12.9%) | 56 (24.2%) | 48 (20.0%) | 4 (6.7%) | 55 (24.4%) | 245 (17.6%) |

| Religious event | 8 (1.3%) | 19 (8.2%) | 6 (2.5%) | 1 (1.7%) | 4 (1.8%) | 38 (2.7%) |

| Other | 26 (4.1%) | 15 (6.5%) | 30 (12.5%) | 2 (3.3%) | 48 (21.3%) | 121 (8.7%) |

| No information | 162 (25.5%) | 41 (17.7%) | 4 (1.7%) | 14 (23.3%) | 5 (2.2%) | 226 (16.2%) |

| NA | 346 (54.4%) | 91 (39.4%) | 120 (50.0%) | 39 (65.0%) | 110 (48.9%) | 706 (50.7%) |

| Witnessing polio vaccination at another location in the City | ||||||

| No | 340 (53.5%) | 102 (44.2%) | 128 (53.3%) | 46 (76.7%) | 73 (32.4%) | 689 (49.5%) |

| Yes | 296 (46.5%) | 129 (55.8%) | 112 (46.7%) | 14 (23.3%) | 152 (67.6%) | 703 (50.5%) |

| Witnessing polio vaccination at another location outside the City | ||||||

| No | 368 (57.9%) | 145 (62.8%) | 158 (65.8%) | 54 (90.0%) | 114 (50.7%) | 839 (60.3%) |

| Yes | 268 (42.1%) | 86 (37.2%) | 82 (34.2%) | 6 (10.0%) | 111 (49.3%) | 553 (39.7%) |

| Dual Houses | ||||||

| No | 472 (74.2%) | 214 (92.6%) | 199 (82.9%) | 52 (86.7%) | 199 (88.4%) | 1136 (81.6%) |

| Yes | 164 (25.8%) | 17 (7.4%) | 41 (17.1%) | 8 (13.3%) | 26 (11.6%) | 256 (18.4%) |

| Frequency of visit to hometown | ||||||

| Every weekend | 7 (1.1%) | 2 (0.9%) | 2 (0.8%) | 10 (16.7%) | 5(2.2%) | 26 (1.9%) |

| Every month | 17 (2.7%) | 3 (1.3%) | 5 (2.1%) | 9 (15.0%) | 10 (4.4%) | 44 (3.2%) |

| On Eid holidays | 32 (5.0%) | 14 (6.1%) | 16 (6.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 4 (1.8%) | 67 (4.8%) |

| Summer holidays | 14 (2.2%) | 8 (3.5%) | 5 (2.1%) | 5 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 32 (2.3%) |

| Family events | 205 (32.2%) | 47 (20.3%) | 56 (23.3%) | 24 (40.0%) | 33 (14.7%) | 365 (26.2%) |

| Other | 110 (17.3%) | 21 (9.1%) | 75 (31.3%) | 10 (16.7%) | 85 (37.8%) | 301 (21.6%) |

| No information | 251 (39.4%) | 136 (58.8%) | 81 (33.8%) | 1 (1.7%) | 88 (39.1%) | 557 (40.0%) |

| Purpose of staying here | ||||||

| Business | 26 (4.1%) | 53 (22.9%) | 43 (17.9%) | 2 (3.3%) | 59 (26.2%) | 183 (13.2%) |

| Education | 9 (1.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 6 (2.5%) | 4 (6.7%) | 3 (1.3%) | 23 (1.7%) |

| Family event | 7 (1.1%) | 6 (2.6%) | 6 (2.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.3%) | 22 (1.6%) |

| Job | 143 (22.5%) | 79 (34.2%) | 136 (56.7%) | 51 (85.0%) | 101 (44.9%) | 510 (36.6%) |

| Other | 30 (4.7%) | 8 (3.5%) | 12 (5.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 18 (8.0%) | 69 (5.0%) |

| No information | 421 (66.1%) | 84 (36.4%) | 37 (15.4%) | 2 (3.3%) | 41 (18.2%) | 585 (42.0%) |

| Source of income | ||||||

| Business | 0 (0.0%) | 38 (16.4%) | 39 (16.3%) | 6 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 83 (6.0%) |

| Farmer | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.3%) | 8 (13.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (0.8%) |

| Govt. job | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (3.5%) | 11 (4.6%) | 1(1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 20 (1.5%) |

| Job | 143 (22.5%) | 9 (3.9%) | 3 (1.3%) | 1(1.7%) | 101 (44.9%) | 257 (18.5%) |

| Private job | 0 (0.0%) | 66 (28.6%) | 134 (55.8%) | 38 (63.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 238 (17.1%) |

| Shopkeeper | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (4.8%) | 9 (3.8%) | 4 (6.7%) | 0(0.0%) | 24 (1.7%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 45 (195%) | 28 (11.7%) | 2 (3.3%) | 0(0.0%) | 75 (5.4%) |

| No information | 493 (77.4%) | 53 (22.9%) | 13 (5.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 124 (55.1%) | 683 (49.1%) |

| Variable | Badin | Hyderabad | Kambar | Mirpurkhas | SBA | Sujawal | Sukkur | Sindh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 146) | (N = 498) | (N = 136) | (N = 228) | (N = 89) | (N = 60) | (N = 314) | (N = 1471) | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 102 (69.9%) | 313 (62.9%) | 10 (7.4%) | 127 (55.7%) | 26 (29.2%) | 11 (18.3%) | 205 (65.3%) | 749 (54.0%) |

| Male | 44 (30.1%) | 184 (36.9%) | 126 (92.6%) | 100 (43.9%) | 63 (70.8%) | 49 (81.7%) | 109 (34.7%) | 675 (45.9%) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 38.838 (10.9597) | 35.192 (7.7780) | 36.978 (7.7378) | 34.119 (10.4921) | 36.865 (9.9569) | 33.750 (8.0478) | 36.965 (9.7752) | 35.973 (9.2622) |

| Language | ||||||||

| Balochi | 2 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 25 (11.0%) | 15 (16.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 38 (12.1%) | 80 (5.4%) |

| Pashto | 20 (13.7%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 31 (9.9%) | 53 (3.6%) |

| Punjabi | 12 (8.2%) | 13 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 18 (7.9%) | 11 (12.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (1.0%) | 57 (3.9%) |

| Sindhi | 90 (61.6%) | 68 (13.7%) | 96 (70.6%) | 106 (46.5%) | 6 (6.7%) | 58 (96.7%) | 77 (24.5%) | 501 (34.1%) |

| Siraiki | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (0.1%) | 16 (18.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 28 (8.9%) | 49 (3.3%) |

| Urdu | 22 (15.1%) | 412 (82.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 64 (28.1%) | 38 (42.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 97 (30.9%) | 633 (43.0%) |

| Others | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.4%) | 39 (28.7%) | 12 (5.3%) | 3 (3.4%) | 2 (3.3%) | 40 (12.7%) | 98 (6.7%) |

| Number of children under five years of age (mean ± SD) | 1.589 (0.9371) | 1.596 (0.7922) | 2.213 (1.0357) | 1.732 (0.9020) | 1.708 (0.9909) | 1.800 (0.9881) | 2.226 (1.5407) | 1.823 (1.0955) |

| OPV vaccination in SIA status | ||||||||

| No response | 4 (2.7%) | 2 (0.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (2.2%) | 2 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (0.9%) |

| No | 2 (1.4%) | 15 (3.0%) | 3 (2.2%) | 7 (3.1%) | 2 (2.2%) | 2 (3.3%) | 5 (1.6%) | 36 (2.4%) |

| Yes | 140 (95.9%) | 481 (96.6%) | 133 (97.8%) | 216 (94.7%) | 85 (95.5%) | 58 (96.7%) | 309 (98.4%) | 1422 (96.7%) |

| RI status | ||||||||

| No | 6 (4.1%) | 59 (11.8%) | 33 (24.3%) | 25 (11.0%) | 5 (5.6%) | 3 (5.0%) | 67 (21.3%) | 198 (13.5%) |

| Yes partial | 14 (9.6%) | 30 (6.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 102 (44.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 92 (29.3%) | 238 (16.2%) |

| Yes complete | 126 (86.3%) | 409 (82.1%) | 103 (75.7%) | 101 (44.3%) | 84 (94.4%) | 57 (95.0%) | 155 (49.4%) | 1035 (70.4%) |

| Guest arrival | ||||||||

| No | 34 (23.3%) | 52 (10.4%) | 62 (45.6%) | 79 (34.6%) | 43 (48.3%) | 12 (20.0%) | 95 (30.3%) | 377 (25.6%) |

| Yes | 112 (76.7%) | 446 (89.6%) | 74 (54.4%) | 149 (65.4%) | 46 (51.7%) | 48 (80.0%) | 219 (69.7%) | 1094 (74.4%) |

| Any Guest children vaccinated | ||||||||

| No response | 10 (6.8%) | 89 (17.9%) | 118 (86.8%) | 119 (52.2%) | 73 (82.0%) | 42 (70.0%) | 172 (54.8%) | 623 (42.4%) |

| No | 120 (82.2%) | 23 (4.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 52 (22.8%) | 3 (3.4%) | 1 (1.7%) | 67 (21.3%) | 266 (18.1%) |

| Yes | 16 (11.0%) | 386 (77.5%) | 18 (13.2%) | 57 (25.0%) | 13 (14.6%) | 17 (28.3%) | 75 (23.9%) | 582 (39.6%) |

| Travel history | ||||||||

| No | 40 (27.4%) | 159 (31.9%) | 123 (90.4%) | 123 (53.9%) | 31 (34.8%) | 10 (16.7%) | 120 (38.2%) | 606 (41.2%) |

| Yes | 106 (72.6%) | 339 (68.1%) | 13 (9.6%) | 105 (46.1%) | 58 (65.2%) | 50 (83.3%) | 194 (61.8%) | 865 (58.8%) |

| Purpose of travel | ||||||||

| Business | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 14 (6.1%) | 5 (5.6%) | 5 (8.3%) | 31 (9.9%) | 65 (4.4%) |

| Education | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Family event | 0 (0.0%) | 46(9.2%) | 1 (0.7%) | 38 (16.7%) | 28 (31.5%) | 13 (21.7%) | 64 (20.4%) | 190 (12.9%) |

| Job | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (1.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (2.6%) | 10 (11.2%) | 1 (1.7%) | 13 (4.1%) | 37 (2.5%) |

| Religious event | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (8.3%) | 4 (1.3%) | 24 (1.6%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 57 (11.4%) | 9 (6.6%) | 3 (1.3%) | 10 (11.2%) | 11 (18.3%) | 73(23.2%) | 163 (11.1%) |

| No information | 106 (72.6%) | 215 (43.2%) | 3 (2.2%) | 32 (14.0%) | 5 (5.6%) | 15 (25.0%) | 10 (3.2%) | 386 (26.2%) |

| NA | 40 (27.4%) | 159 (31.9%) | 123 (90.4%) | 123 (53.9%) | 31(34.8%) | 10 (16.7%) | 119 (37.9%) | 605 (41.1%) |

| Witnessing polio vaccination at another location in the City | ||||||||

| No | 18 (12.3%) | 58 (11.6%) | 132 (97.1%) | 87 (38.2%) | 55 (61.8%) | 29 (48.3%) | 150 (47.8%) | 529 (36.0%) |

| Yes | 128 (87.7%) | 440 (88.4%) | 4 (2.9%) | 141 (61.8%) | 34 (38.2%) | 31 (51.7%) | 164 (52.2%) | 942 (64.0%) |

| Witnessing polio vaccination at another location outside the City | ||||||||

| No | 82 (56.2%) | 128 (25.7%) | 132 (97.1%) | 140 (61.4%) | 62 (69.7%) | 38 (63.3%) | 191 (60.8%) | 773 (52.5%) |

| Yes | 64 (43.8%) | 370 (74.3%) | 4 (2.9%) | 88 (38.6%) | 27 (30.3%) | 22 (36.7%) | 123 (39.2) | 698 (47.5%) |

| Dual Houses | ||||||||

| No | 128 (87.7%) | 417 (83.7%) | 132 (97.1%) | 186 (81.6%) | 83 (93.3%) | 52 (86.7%) | 243 (77.4%) | 1241 (84.4%) |

| Yes | 18 (12.3%) | 81 (16.3%) | 4 (2.9%) | 42 (18.4%) | 6 (6.7%) | 8 (13.3%) | 71 (22.6%) | 230 (15.6%) |

| Frequency of visit to hometown | ||||||||

| Every month | 4 (2.7%) | 24 (4.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (5.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.7%) | 3 (1.0%) | 45 (3.1%) |

| Every weekend | 6 (4.1%) | 4 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 13 (0.9%) |

| Family events | 8 (5.5%) | 153 (30.7%) | 2 (1.5%) | 25 (11.0%) | 21 (23.6%) | 5 (8.3%) | 99 (31.5%) | 313 (21.3%) |

| Summer holidays | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (2.0%) | 3 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (3.2%) | 23 (1.6%) |

| On Eid holidays | 14 (9.6%) | 18 (3.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 19 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (3.8%) | 63 (4.3%) |

| Other | 32 (21.9%) | 33 (6.6%) | 4 (2.9%) | 17 (7.5%) | 4 (4.5%) | 1 (1.7%) | 66 (21.0%) | 157 (10.7%) |

| No information | 82 (56.2%) | 175 (35.1%) | 4 (2.9%) | 153 (67.1%) | 50 (56.2%) | 2 (3.3%) | 123 (39.2%) | 589 (40.0%) |

| NA | 0 (0.0%) | 81 (16.3%) | 123 (90.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (14.6%) | 51(85.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 268 (18.2%) |

| Purpose of staying here | ||||||||

| Business | 0 (0.0%) | 47 (9.4%) | 4 (2.9%) | 80 (35.1%) | 48 (53.9%) | 9 (15.0%) | 90 (28.7%) | 278 (18.9%) |

| Education | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 4 (0.3%) |

| Family event | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (1.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 8 (2.5%) | 18 (1.2%) |

| Job | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 24 (10.5%) | 20 (22.5%) | 3 (5.0%) | 39 (12.4%) | 95 (6.5%) |

| Any other | 0 (0.0%) | 61 (12.2%) | 11 (8.1%) | 4 (1.8%) | 13 (14.6%) | 14 (23.3%) | 118 (37.6%) | 221 (15.0%) |

| No Information | 146 (100.0%) | 375 (75.3%) | 120 (88.2%) | 115 (50.4%) | 8 (9.0%) | 33 (55.0%) | 58 (18.5%) | 855 (58.1%) |

| Source of income | ||||||||

| Business | 0 (0.0%) | 53 (10.6%) | 5 (3.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 18 (20.2%) | 13 (21.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 89 (6.1%) |

| Farmer | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | 88 (64.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (3.4%) | 3 (5.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 95 (6.5%) |

| Govt. job | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (5.6%) | 2 (3.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (0.7%) |

| Job | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 24 (10.5%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 39 (12.4%) | 64 (4.4%) |

| Private job | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (7.9%) | 8(13.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 27 (1.8%) |

| Shopkeeper | 0 (0.0%) | 25 (5.0%) | 3 (2.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 24 (27.0%) | 4 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 56 (3.8%) |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 73 (14.7%) | 40 (29.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 25 (28.1%) | 29 (48.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 167 (11.4%) |

| No information | 146 (100.0%) | 331 (66.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 204 (89.5%) | 6 (6.7%) | 1 (1.7%) | 275 (87.6%) | 963 (65.5%) |

| Variable | Karachi | Sindh | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 1392) | (N = 1471) | (N = 2863) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 972 (55.0%) | 794 (45.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Male | 420 (38.4%) | 675 (61.6%) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 34.170 (9.5103) | 35.973 (9.2622) | <0.0001 |

| Language | |||

| Balochi | 81 (50.3%) | 80 (49.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Pashto | 336 (86.4%) | 53 (13.6%) | |

| Punjabi | 155 (73.1%) | 57 (26.9%) | |

| Sindhi | 130 (20.6%) | 501 (79.4%) | |

| Siraiki | 118 (70.7%) | 49 (29.3%) | |

| Urdu | 376 (37.3%) | 633 (62.7%) | |

| Others | 196 (66.7%) | 98 (33.3%) | |

| Number of children under five years of age (mean ± SD) | 1.599 (0.9706) | 1.823 (1.0955) | <0.0001 |

| OPV vaccination in SIA status | |||

| No response | 15 (53.6%) | 13 (46.4%) | 0.003 |

| No | 67 (65.0%) | 36 (35.0%) | |

| Yes | 1310 (48.0%) | 1422 (52.0%) | |

| RI status | |||

| No | 131 (39.8%) | 198 (60.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Yes partial | 344 (59.1%) | 238 (40.9%) | |

| Yes complete | 917 (47.0%) | 1035 (53.0%) | |

| Guest arrival | |||

| No | 334 (47.0%) | 377 (53.0%) | 0.312 |

| Yes | 1058 (49.2%) | 1094 (50.08%) | |

| Any Guest children vaccinated | |||

| No response | 683 (52.3%) | 623 (47.7%) | <0.0001 |

| No | 345 (56.5%) | 266 (43.5%) | |

| Yes | 364 (38.5%) | 582 (61.5%) | |

| Travel history | |||

| No | 706 (53.8%) | 606 (46.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 686 (44.2%) | 865 (55.8%) | |

| Purpose of travel | |||

| Business | 5 (7.1%) | 65 (92.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Education | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | |

| Family event | 245 (56.3%) | 190 (43.7%) | |

| Job | 50 (57.5%) | 37 (42.5%) | |

| Religious event | 38 (61.3%) | 24 (38.7%) | |

| Other | 121 (42.6%) | 163 (57.4%) | |

| No information | 226 (36.9%) | 386 (63.1%) | |

| NA | 706 (53.9%) | 605 (46.1%) | |

| Witnessing polio vaccination at another location in the City | |||

| No | 689 (56.6%) | 529 (43.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 703 (42.7%) | 942 (57.3%) | |

| Witnessing polio vaccination at another location outside the City | |||

| No | 839 (52.0%) | 773 (48.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 553 (44.2%) | 698 (55.8%) | |

| Dual Houses | |||

| No | 1136 (47.8%) | 1241 (52.2%) | 0.050 |

| Yes | 256 (52.7%) | 230 (47.3%) | |

| Frequency of visit to hometown | |||

| Every month | 44 (49.4%) | 45 (50.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Every weekend | 26 (66.7%) | 13 (33.3%) | |

| Family events | 365 (53.8%) | 313 (46.2%) | |

| Summer holidays | 32 (58.2%) | 23 (41.8%) | |

| On Eid holidays | 67 (51.5%) | 63 (48.5%) | |

| Other | 301 (65.7%) | 157 (34.3%) | |

| No information | 557 (48.6%) | 589 (51.4%) | |

| NA | 0 (0%) | 268 (100.0%) | |

| Purpose of staying here | |||

| Business | 183 (39.7%) | 278 (60.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Education | 23 (85.2%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| Family event | 22 (55.0%) | 18 (45.0%) | |

| Job | 510 (84.3%) | 95 (15.7%) | |

| Other | 69 (23.8%) | 221 (76.2%) | |

| No information | 585 (40.6%) | 855 (59.4%) | |

| Source of income | |||

| Business | 83 (48.3%) | 89 (51.7%) | <0.0001 |

| Farmer | 12 (11.2%) | 95 (88.8%) | |

| Govt. job | 20 (66.7%) | 10 (33.3%) | |

| Job | 257 (80.1%) | 64 (19.9%) | |

| Private job | 238 (89.8%) | 27 (10.2%) | |

| Shopkeeper | 24 (30.0%) | 56 (70.0%) | |

| Other | 75 (31.0%) | 167 (69.0%) | |

| No information | 683 (41.5%) | 963 (58.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sodhar, I.A.; Mehraj, J.; Hussaini, A.S.; Ahmed, S.; Shaikh, A.A.; Zardari, A.A.; Sahitia, S.; Rasool, S.; Khowaja, A.; Stuckey, E.M. Redefining High-Risk and Mobile Population in Pakistan Polio Eradication Program; 2024. Vaccines 2025, 13, 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13101016

Sodhar IA, Mehraj J, Hussaini AS, Ahmed S, Shaikh AA, Zardari AA, Sahitia S, Rasool S, Khowaja A, Stuckey EM. Redefining High-Risk and Mobile Population in Pakistan Polio Eradication Program; 2024. Vaccines. 2025; 13(10):1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13101016

Chicago/Turabian StyleSodhar, Irshad Ali, Jaishri Mehraj, Anum S. Hussaini, Shabbir Ahmed, Ahmed Ali Shaikh, Asif Ali Zardari, Sundeep Sahitia, Shumaila Rasool, Azeem Khowaja, and Erin M. Stuckey. 2025. "Redefining High-Risk and Mobile Population in Pakistan Polio Eradication Program; 2024" Vaccines 13, no. 10: 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13101016

APA StyleSodhar, I. A., Mehraj, J., Hussaini, A. S., Ahmed, S., Shaikh, A. A., Zardari, A. A., Sahitia, S., Rasool, S., Khowaja, A., & Stuckey, E. M. (2025). Redefining High-Risk and Mobile Population in Pakistan Polio Eradication Program; 2024. Vaccines, 13(10), 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13101016