The Addis Declaration on Immunization: Assessing the Effectiveness and Efficiency of Immunization Service Delivery Systems in Africa as of the End of 2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Presentation of the Fourth ADI Commitment

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Sources and Measurement

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

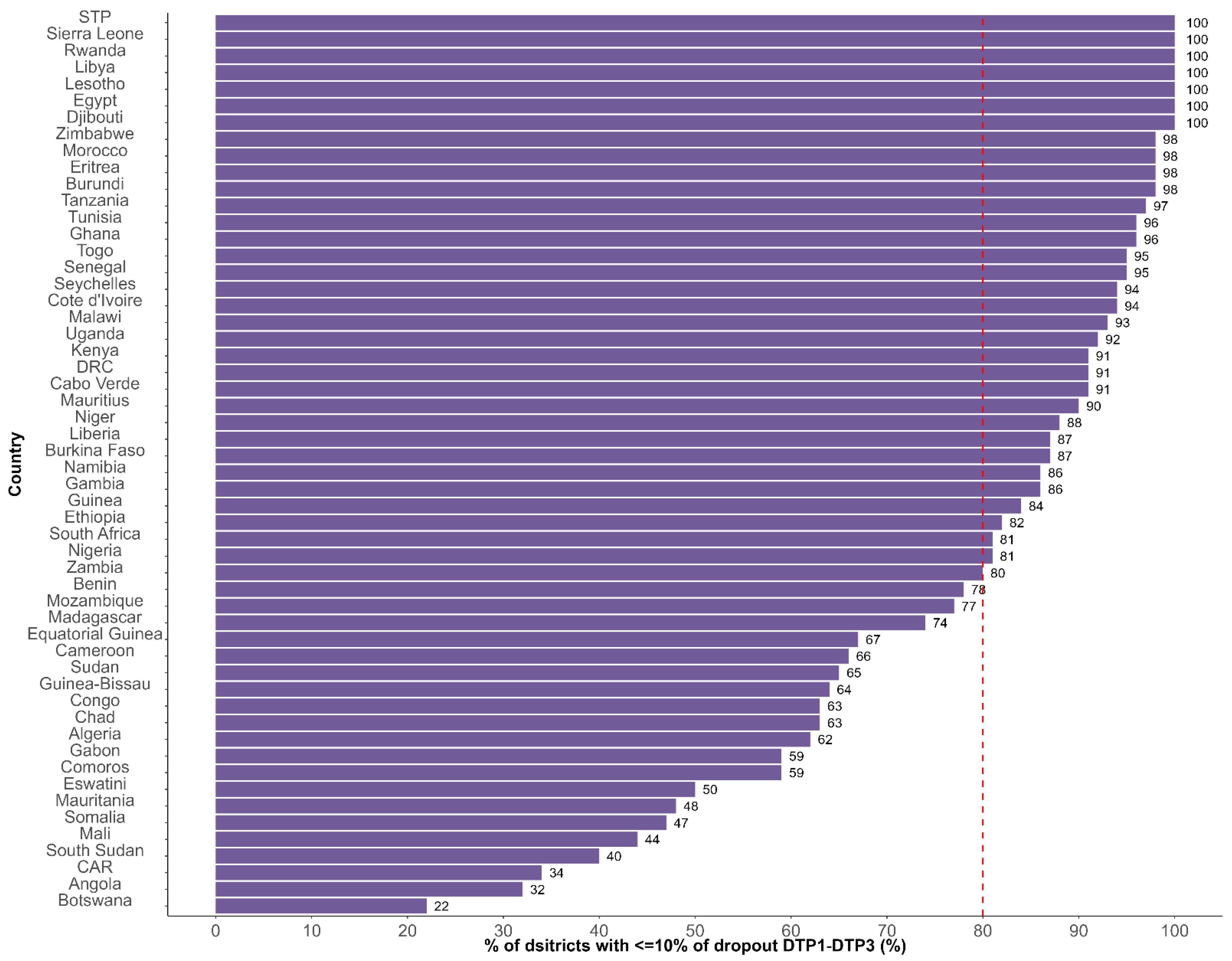

3.1. Indicator 1: Proportion of Countries with More than 80% of Districts Recording Less than 10% Dropout Rate Between DTP1 and DTP3

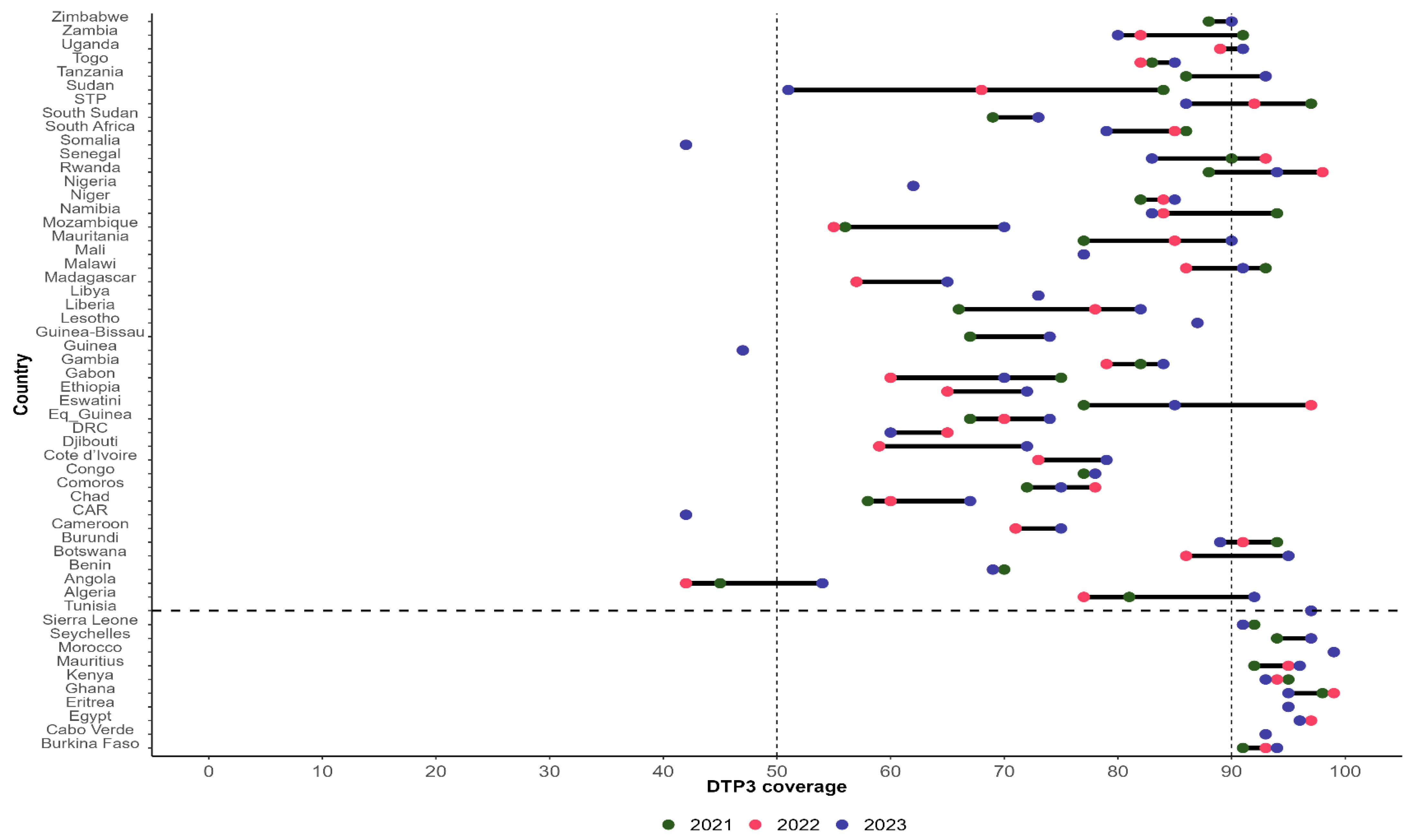

3.2. Indicator 2: Proportion of Countries with Sustained Coverage of at Least 90% for DPT3 in the Past Three Years (2021, 2022, and 2023)

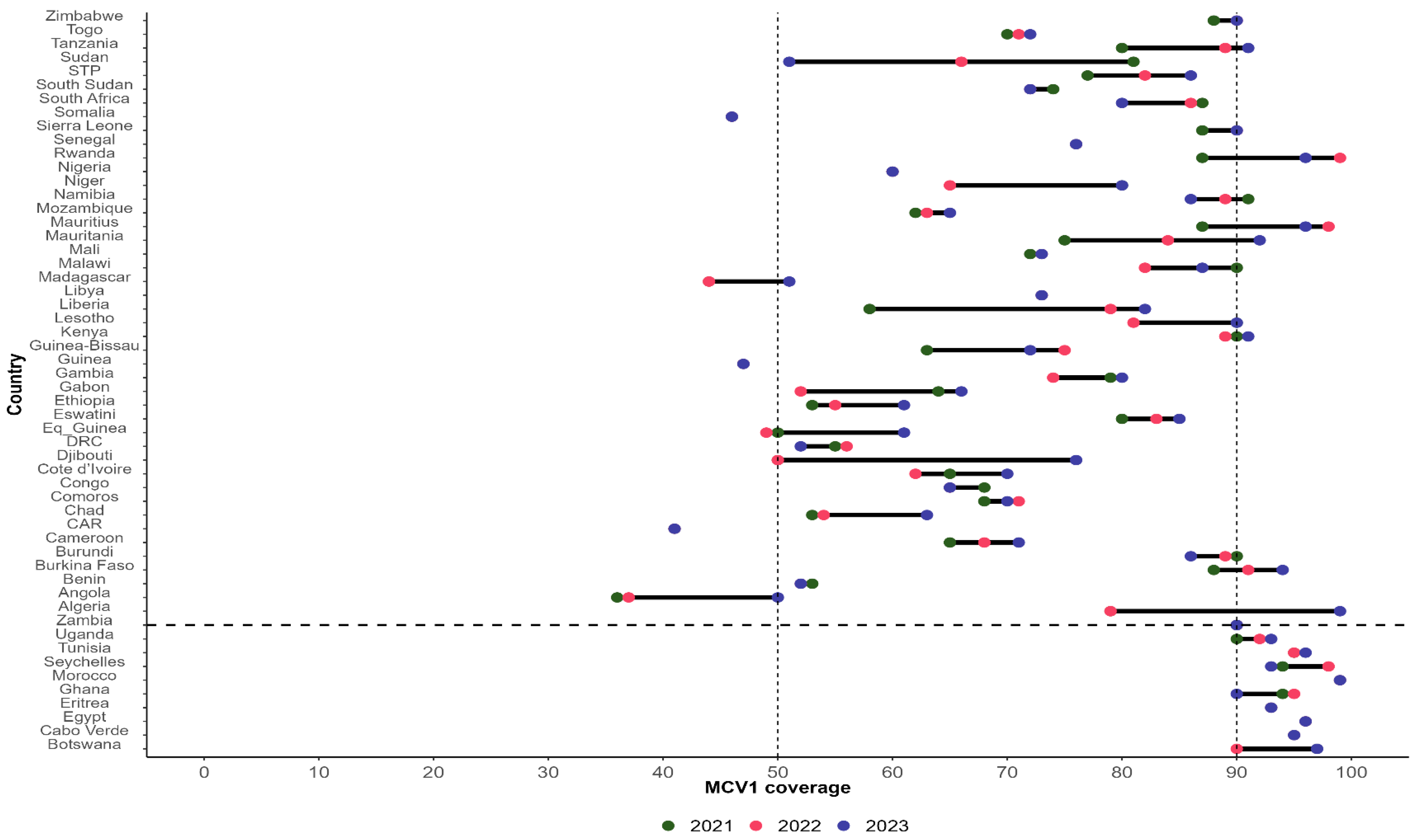

3.3. Indicator 3: Proportion of Countries with Sustained Coverage of at Least 90% for MCV1 in the Past Three Years (2021, 2022, and 2023)

3.4. Indicator 4: Proportion of Countries with a Minimum Threshold of 44.5 Skilled Health Workers per 10,000 People at the National Level in 2022

3.5. Achievement of the Commitment

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feldstein, L.R.; Mariat, S.; Gacic-Dobo, M.; Diallo, M.S.; Conklin, L.M.; Wallace, A.S. Global Routine Vaccination Coverage, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 1252–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. 1 in 5 Children in Africa do Not Have Access to Life-Saving Vaccines. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/1-5-children-africa-do-not-have-access-life-saving-vaccines (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Mihigo, R.M.; Okeibunor, J.C.; Karmal, F.; O’Malley, H.; Godinho, N.; Okero, L.; Poy, A.N.; Onyango, O.; Fitzgerald, N. The Addis Declaration on Immunization: A binding reminder of the political support needed to achieve universal immunization in Africa. Vaccine 2022, 40, 5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Roadmap for Implementing the Addis Declaration on Immunization: Advocacy, Action, and Accountability. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/roadmap-implementing-addis-declaration-immunization-advocacy-action-and-accountability (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Fulfilling a Promise: Ensuring Immunization for all in Africa. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-12/MCIA%20Report.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- Sharma, M.; Singh, S.K.; Sharma, L.; Dwiwedi, M.K.; Agarwal, D.; Gupta, G.K.; Dhiman, R. Magnitude and causes of routine immunization disruptions during COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burki, T. WHO ends the COVID-19 public emergency. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giorgio, L.; Moses, M.W.; Fullman, N.; Wollum, A.; Conner, R.O.; Achan, J.; Achoki, T.; Bannon, K.A.; Burstein, R.; Dansereau, E.; et al. The potential to expand antiretroviral therapy by improving health facility efficiency: Evidence from Kenya, Uganda, and Zambia. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Countries. Available online: https://www.who.int/countries (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Process. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/immunization-analysis-and-insights/global-monitoring/who-unicef-joint-reporting-process (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- World Health Organization. Subnational Immunization Coverage Data. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/immunization-analysis-and-insights/surveillance (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Burton, A.; Monasch, R.; Lautenbach, B.; Gacic-Dobo, M.; Neill, M.; Karimov, R.; Wolfson, L.; Jones, G.; Birmingham, M. WHO and UNICEF estimates of national infant immunization coverage: Methods and processes. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009, 87, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Immunization Data Portal. Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/global?topic=&location= (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- World Health Organization. National Health Workforce Accounts Data Portal. Available online: https://apps.who.int/nhwaportal/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- R Core Team. The R Project for Statistical Computing. 2020. Available online: https://www.r-project.org (accessed on 18 November 2024).

- ESRI. ArcGIS: The Mapping and Analytics Platform. Available online: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/about-arcgis/overview (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Dhalaria, P.; Kapur, S.; Singh, A.K.; Priyadarshini, P.; Dutta, M.; Arora, H.; Taneja, G. Exploring the Pattern of Immunization Dropout among Children in India: A District-Level Comparative Analysis. Vaccines 2023, 11, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Routine Immunization Strategies and Practices (GRISP): A Companion Document to the Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP). Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/essential-programme-on-immunization/implementation/global-routine-immunization-strategies-and-practices-(grisp) (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- Kirkby, K.; Bergen, N.; Schlotheuber, A.; Sodha, S.V.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C.; Hosseinpoor, A.R. Subnational inequalities in diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunization in 24 countries in the African Region. Bull. World Health Organ. 2021, 99, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mboussou, F.; Kada, S.; Danovaro-Holliday, M.C.; Farham, B.; Gacic-Dobo, M.; Shearer, J.C.; Bwaka, A.; Amani, A.; Ngom, R.; Vuo-Masembe, Y.; et al. Status of Routine Immunization Coverage in the World Health Organization African Region Three Years into the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2024, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okesanya, O.J.; Olatunji, G.; Olaleke, N.O.; Mercy, M.O.; Ilesanmi, A.O.; Kayode, H.H.; Manirambona, E.; Ahmed, M.; Ukoaka, B.M.; Lucero-Prisno Iii, D.E. Advancing Immunization in Africa: Overcoming Challenges to Achieve the 2030 Global Immunization Targets. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2024, 15, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaFond, A.; Kanagat, N.; Steinglass, R.; Fields, R.; Sequeira, J.; Mookherji, S. Drivers of routine immunization coverage improvement in Africa: Findings from district-level case studies. Health Policy Plan. 2015, 30, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Reaching Every District (RED)-A Guide to Increasing Coverage and Equity in All Communities in the African Region. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/reaching-every-district-red-guide-increasing-coverage-and-equity-all-communities (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Vandelaer, J.; Bilous, J.; Nshimirimana, D. Reaching Every District (RED) approach: A way to improve immunization performance. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008, 86, A–B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cometto, G.; Campbell, J. Investing in human resources for health: Beyond health outcomes. Hum Resour Health 2016, 14, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Eligibility. Available online: https://www.gavi.org/types-support/sustainability/eligibility (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Fund for Peace. Fragile States Index Annual Report 2023. Available online: https://fragilestatesindex.org/2023/06/14/fragile-states-index-2023-annual-report/ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

| Commitment Number | Commitment Description |

|---|---|

| 01 | Keep universal access to immunization at the forefront of efforts to reduce child mortality. |

| 02 | Increase and sustain domestic investments and funding allocations for immunization. |

| 03 | Address the persistent barriers in vaccine and healthcare delivery systems, especially in the poorest, vulnerable, and most marginalized communities. |

| 04 | Increase the effectiveness and efficiency of immunization delivery systems as an integrated part of strong and sustainable primary health care systems. |

| 05 | Attain and maintain high-quality surveillance for targeted vaccine-preventable diseases. |

| 06 | Monitor progress toward achieving the goals of the global and regional immunization plans. |

| 07 | Ensure polio legacy transition plans are in place. |

| 08 | Develop a capacitated African research sector to enhance immunization implementation and uptake. |

| 09 | Promote and invest in regional capacity for the development and production of vaccines. |

| 10 | Build broad political will for universal access to life-saving vaccines. |

| ADI Indicator | Country Level Indicator | Country Target | Source of Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Proportion of countries with over 80% of districts that recorded less than 10% dropout rate between DTP1 and DTP3 | % of districts with a dropout rate of less than 10% between DTP1 and DTP3 | ≥80% | JRF * [10], accessible on WIISE Mart ** [11] |

| 2. Proportion of countries with sustained coverage of 90% or above for DPT3 in the past three years | DTP3 coverage in the past three years | ≥90% in each of the past three years | WUENIC *** [12] accessible on the WHO Immunization Data Portal [13] |

| 3. Proportion of countries with sustained coverage of at least 90% for MCV1 in the past three years. | MCV1 coverage in the past 3 years | ≥90% in each of the past three years | WUENIC |

| 4. Proportion of countries with a minimum threshold of 44.5 skilled health workers per 10,000 people at the national level | Skilled health workers per 10,000 people at the national level | ≥44.5/10,000 | NHWA **** [14] |

| Country | Indicator 1 Achieved? | Indicator 2 Achieved? | Indicator 3 Achieved? | Indicator 4 Achieved? | Total Indicators Achieved | % Indicators Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Angola | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Benin | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Botswana | No | No | Yes | No | 1 | 25 |

| Burkina Faso | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 | 50 |

| Burundi | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Cabo Verde | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | 100 |

| Cameroon | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Central African Republic | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Chad | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Comoros | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Congo | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Cote d’Ivoire | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Djibouti | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Egypt | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 75 |

| Equatorial Guinea | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Eritrea | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 75 |

| Eswatini | No | No | No | Yes | 1 | 25 |

| Ethiopia | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Gabon | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Gambia | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Ghana | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 75 |

| Guinea | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Guinea-Bissau | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Kenya | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 | 50 |

| Lesotho | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Liberia | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Libya | Yes | No | No | Yes | 2 | 50 |

| Madagascar | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Malawi | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Mali | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Mauritania | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Mauritius | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 | 50 |

| Morocco | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 75 |

| Mozambique | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Namibia | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Niger | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Nigeria | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Rwanda | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Sao Tome and Principe | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Senegal | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Seychelles | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 | 100 |

| Sierra Leone | Yes | Yes | No | No | 2 | 50 |

| Somalia | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| South Africa | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| South Sudan | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Sudan | No | No | No | No | 0 | 0 |

| Togo | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Tunisia | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | 75 |

| Uganda | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 | 50 |

| Tanzania | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Zambia | Yes | No | Yes | No | 2 | 50 |

| Zimbabwe | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | 25 |

| Total countries that achieved the indicator | 34 | 11 | 10 | 4 | ||

| % countries that achieved the indicator | 63 | 20 | 19 | 7 | ||

| Legend | ||||||

| Achieved | ||||||

| Not achieved |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© World Health Organization 2024. Licensee MDPI. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution IGO License. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In any reproduction of this article there should not be any suggestion that WHO or this article endorse any specific organization or products. The use of WHO logo is not permitted.

Share and Cite

Mboussou, F.; Wiysonge, C.S.; Farham, B.; Bwaka, A.; Wanyoike, S.; Petu, A.; Ndiaye, S.; Bita Fouda, A.; Ticha, J.M.; Amani, A.; et al. The Addis Declaration on Immunization: Assessing the Effectiveness and Efficiency of Immunization Service Delivery Systems in Africa as of the End of 2023. Vaccines 2025, 13, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13010013

Mboussou F, Wiysonge CS, Farham B, Bwaka A, Wanyoike S, Petu A, Ndiaye S, Bita Fouda A, Ticha JM, Amani A, et al. The Addis Declaration on Immunization: Assessing the Effectiveness and Efficiency of Immunization Service Delivery Systems in Africa as of the End of 2023. Vaccines. 2025; 13(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleMboussou, Franck, Charles Shey Wiysonge, Bridget Farham, Ado Bwaka, Sarah Wanyoike, Amos Petu, Sidy Ndiaye, Andre Bita Fouda, Johnson Muluh Ticha, Adidja Amani, and et al. 2025. "The Addis Declaration on Immunization: Assessing the Effectiveness and Efficiency of Immunization Service Delivery Systems in Africa as of the End of 2023" Vaccines 13, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13010013

APA StyleMboussou, F., Wiysonge, C. S., Farham, B., Bwaka, A., Wanyoike, S., Petu, A., Ndiaye, S., Bita Fouda, A., Ticha, J. M., Amani, A., Obiang, R., Bagayoko, M. M., & Impouma, B. (2025). The Addis Declaration on Immunization: Assessing the Effectiveness and Efficiency of Immunization Service Delivery Systems in Africa as of the End of 2023. Vaccines, 13(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines13010013