A Psychosocial Critique of the Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on UK Care Home Staff Attitudes to the Flu Vaccination: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

Setting the Study Context

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sample and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Tension Between Autonomy and Morals in Vaccination Decisions

We were also threatened with, and it happened, that if you weren’t vaccinated by… the 16th November, you had to leave. And three members of staff left, good members of staff. And I was pleading with them to stay and get vaccinated, and they left.(CHS_002_feasibility)

I do believe that the COVID-19 mandatory vaccinations for care staff had a massive impact on the uptake of the flu vaccine this year… Because that’s what the staff was reporting to me when they weren’t going for it. They weren’t having it because they’d already had enough vaccines.(CHM_003_main)

Personally, I’ve been running this home five years, and I’ve known some staff that had the flu vaccine religiously that haven’t had it this time… Yes. [the COVID-19 mandates] had a negative impact, yes… no one’s bothered since [the flu vaccine] weren’t mandatory, yes.(CHM_003_main)

Our choice obviously was taken away from us because we work in the care sector and now you don’t have to have [vaccines] to work in the care sector so it’s a bit like, we were all forced to otherwise we would have lost our jobs and now we don’t have to so why should you have something that you don’t have to have?(CHS_018_main)

Obviously, at the beginning, when we had to have the [COVID-19] vaccines, even though the NHS didn’t, it’s always, “Why are you picking on care homes?… And now you’re making me have the flu.” It’s like, “No, no, no, we’re not making you have the flu.” … and then we’d all been encouraged to have [the flu jab] but even by the time the third and the fourth [Flu vaccination clinic] was coming now, everyone’s saying, “No, you can’t force me to have it. I’ve had enough. I want to be able to make the choice.”.(CHM_002_main)

I think that then doesn’t come down to necessarily vaccines themselves or COVID-19 vaccines or flu vaccines, but more around staff’s general feeling of being undervalued as a job role, being under valued in pay, being undervalued …it was made mandatory and then it wasn’t made mandatory in health care … I think that there may be a bit of a backlash… I suppose and that’s a way of them kicking back I suppose.(CHM_001_main)

3.2. COVID ‘Craze’ and Displacement of Flu Vaccine

I don’t know anyone who’s been really ill from flu. But I know people get ill from flu, but it’s a normal illness, not anything that’s going to make me think oh I need to protect myself … With COVID-19 there a visual, you see people getting really ill, it’s different isn’t it. It makes you want to take it. But if don’t know anybody who’s had the flu, why would you take it?(CHS_008_feasibility)

Now we all have COVID-19 vaccination, so I don’t think flu jab is needed in the future as well. So, what’s the point of flu jab when we have COVID-19 vaccinations, … Yes, before COVID-19 vaccination I agree, we should take [the flu vaccine]. But after COVID-19 vaccination I don’t think it makes any sense to take now flu jabs.(CHS_007_feasibility)

3.3. Role of the COVID ‘Craze’ in Staff Vaccine Fatigue

I think the positives in the [FluCare] idea was good. The fact that we were trying to arrange clinics in the home was good, to actually bring them to us, rather than us say, “Go to your GP or go to your pharmacy.” But I just think we just fell really short of the mark, and again, that’s the timing. That’s the timing of it, and that’s COVID-19, and that’s due to the fatigue. Nothing to do with the FluCare promotion or study at all.(CHM_002_main)

I suppose some people may be getting tired of vaccines, you know, there’s been quite a lot recently…–if you took all the COVID-19 ones. I suppose there’s been about five now altogether, if everybody took everything, and a flu on top, maybe people are thinking that’s too much.(CHS_003_main)

Everyone’s a little bit more hesitant, and especially with having both at the same time, because they were offering us [the COVID-19 and flu vaccines] at the same time. And [staff] were like “no it hasn’t really been tested, has it?” I know they say it has but until you have a long-term thing then they’re worried about two different vaccinations at the same time, what are they going to do? Are they going to react?(CHS_005_feasibility)

3.4. Conspiracies, (Mis)information, and the Significance of Trust

You get all the social media don’t you where they say that they’re going to add stuff into the flu vaccine to cover COVID-19 and all that. Because obviously some of our staff didn’t want the COVID-19… so they’re worried that they’re then going to put something in there which made them a little bit worried.(CHS_005_feasibility)

With the controversy that we all had the AstraZeneca… where they were claiming that it was perfectly safe, there’s no evidence of the blood clots… and they adamantly said that, and they were told that by [the governmental department] Infection Control, the same people that are telling them to have the flu vaccination. So, they were told by those same people that there was no issues, and then it all came out that, actually, there were, and it got taken off the market. By that time, [staff] felt they had been put in danger by people that they trusted, and they do not trust them anymore.(CHS_005_main)

People are used to the same poster and the same leaflets, and we’ve seen it in the NHS hospitals and the posters are everywhere … I think that the better thing that you can do is have proponents of it that will talk about [the flu vaccine] in coffee times, over clearing up, looking after someone … And I think that that does more than the same old leaflet or poster … so I think it’s the spoken voice, the reasoning, and the discussion that people will have that will, if anything, perhaps get those last two or three members of staff through to saying yes to [the flu vaccine].(CHS_002_feasibility)

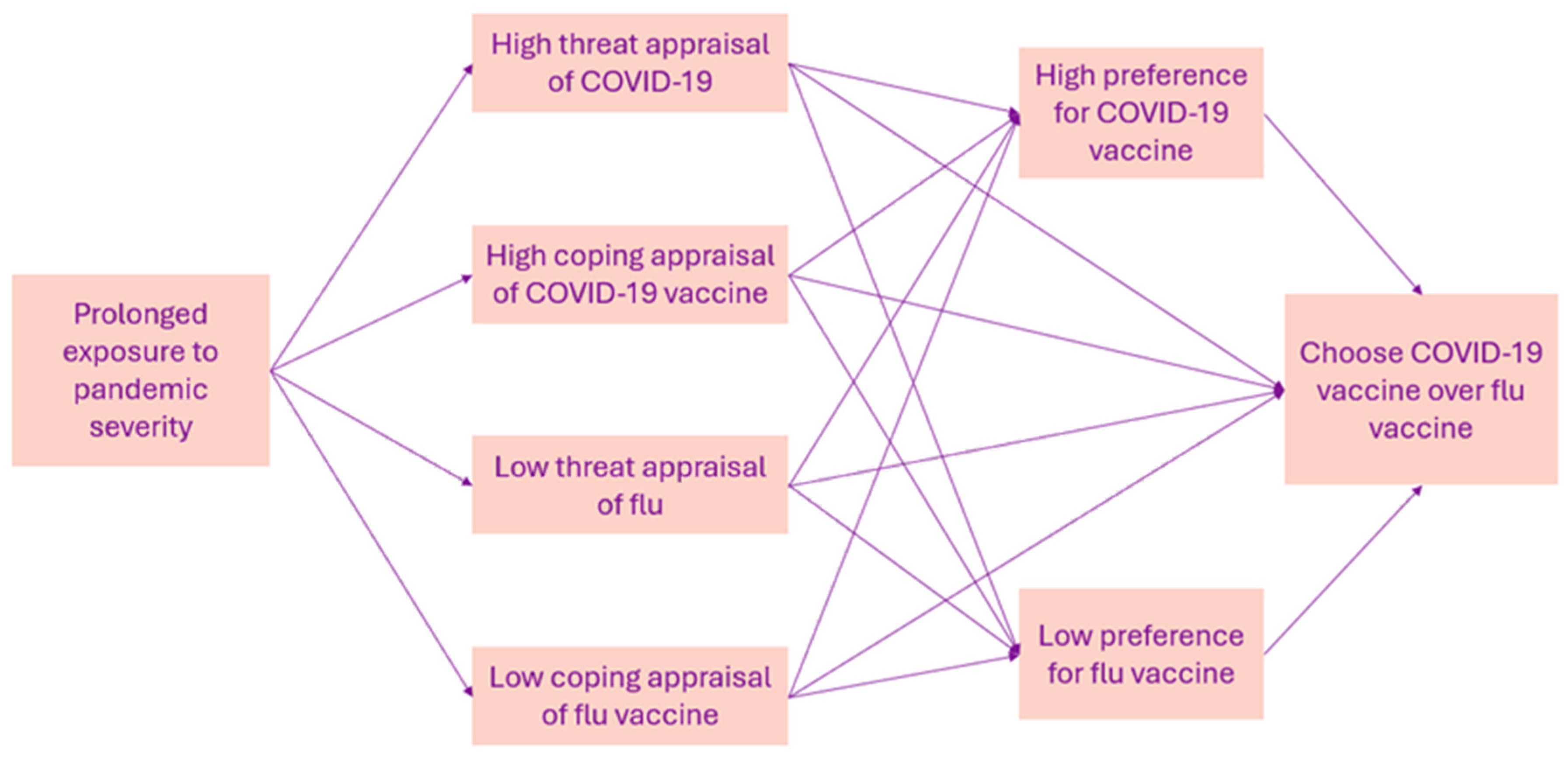

4. Discussion: Theoretical Application

4.1. Desire for Autonomy in Decision Making

4.2. Overexposure and Risk Perception

4.3. Fatigue and Risk Perception

4.4. Source Trustworthiness

4.5. Study Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Clinical Implications and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Vaccination of Health Workers 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/essential-programme-on-immunization/integration/health-worker-vaccination (accessed on 9 October 2024).

- Ahmed, F.; Lindley, M.C.; Allred, N.; Weinbaum, C.M.; Grohskopf, L. Effect of influenza vaccination of healthcare personnel on morbidity and mortality among patients: Systematic review and grading of evidence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Dool, C.; Bonten, M.J.M.; Hak, E.; Heijne, J.C.M.; Wallinga, J. The Effects of Influenza Vaccination of Health Care Workers in Nursing Homes: Insights from a Mathematical Model. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dini, G.; Toletone, A.; Sticchi, L.; Orsi, A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Durando, P. Influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: A comprehensive critical appraisal of the literature. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Northam, H.; Webster, A.; Strickland, K. Determinants of seasonal influenza vaccination hesitancy among healthcare personnel: An integrative review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 2112–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, S.; Paton, D. COVID-19 vaccines as a condition of employment: Impact on uptake, staffing, and mortality in elderly care homes. Manag. Sci. 2023, 70, 2882–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, A.; Robin, C.; Jones, L.; Carter, H. Exploring Vaccine Hesitancy in Care Home Employees in North West England: A Qualitative Study. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, K.; Gogoi, M.; Martin, C.A.; Papineni, P.; Lagrata, S.; Nellums, L.B.; McManus, I.C.; Guyatt, A.L.; Melbourne, C.; Bryant, L. Healthcare workers’ views on mandatory SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in the UK: A cross-sectional, mixed-methods analysis from the UK-REACH study. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 46, 101346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, L.; Haloub, R.; Reid, H.; Masson, D.; McCalmont, H.; Fodey, K.; Conway, B.R.; Lattyak, W.J.; Lattyak, E.A.; Bain, A.; et al. Exploration of the Experience of Care Home Managers of COVID-19 Vaccination Programme Implementation and Uptake by Residents and Staff in Care Homes in Northern Ireland. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, B.; Forbes, G.; Jhass, A.; Lorencatto, F.; Shallcross, L.; Antonopoulou, V. Factors influencing staff attitudes to COVID-19 vaccination in care homes in England: A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulloch, J.S.; Lawrenson, K.; Gordon, A.L.; Ghebrehewet, S.; Ashton, M.; Peddie, S.; Parvulescu, P. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in care home staff: A survey of Liverpool care homes. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1290–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Sims, E.; Blacklock, J.; Birt, L.; Bion, V.; Clark, A.; Griffiths, A.; Guillard, C.; Hammond, A.; Holland, R.; et al. Cluster randomised control trial protocol for estimating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a complex intervention to increase care home staff influenza vaccination rates compared to usual practice (FLUCARE). Trials 2022, 23, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Department of Health and Social Care. Consultation Outcome: Making Covid Vaccination a Condition of Deployment in Care Home: Government Response; Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Skivington, K.; Matthews, L.; Simpson, S.A.; Craig, P.; Baird, J.; Blazeby, J.M.; Boyd, K.A.; Craig, N.; French, D.P.; McIntosh, E. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2021, 374, n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birt, L.; Katangwe-Chigamba, T.; Scott, S.; Wright, D.J.; Wagner, A.P.; Sims, E.; Bion, V.; Seeley, C.; Alsaif, F.; Clarke, A.; et al. Protocol of the process evaluation of cluster randomised control trial for estimating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a complex intervention to increase care home staff influenza vaccination rates compared to usual practice (FluCare). Trials 2023, 24, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, J.W. A theory of Psychological Reactance; Academic Press: Academic, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Steindl, C.; Jones, E.; Sittenthaler, S.; Traut-Mattausch, E.; Greenberg, J. Understanding Psychological Reactance. Z. Psychol. 2015, 223, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriss, L.A.; Quick, B.L.; Rains, S.A.; Barbati, J.L. Psychological Reactance Theory and COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates: The Roles of Threat Magnitude and Direction of Threat. J. Health Commun. 2022, 27, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokhari, R.; Shazad, K. Explaining Resistance to the COVID-19 Preventive Measures: A Psychological Reactance Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Sun, Y. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: The effects of combining direct and indirect online opinion cues on psychological reactance to health campaigns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodger, D.; Blackshaw, B.P. COVID-19 Vaccination Should not be Mandatory for Health and Social Care Workers. New Bioeth. 2022, 28, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprengholz, P.; Betsch, C.; Böhm, R. Reactance revisited: Consequences of mandatory and scarce vaccination in the case of COVID-19. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021, 13, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze, A.; Nightingale, E.; Evans, D.; Hulme, W.; Rosello, A.; Bates, C.; Cockburn, J.; MacKenna, B.; Curtis, H.J.; Morton, C.E.; et al. Mortality among Care Home Residents in England during the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic: An observational study of 4.3 million adults over the age of 65. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2022, 14, 100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, R.W. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In Social Psychology: A Sourcebook; Cacioppo, J.R., Petty, R.E., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bottemanne, H.; Friston, K.J. An active inference account of protective behaviours during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 21, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, M.; Kothe, E.J.; Mullan, B.A. Predicting intention to receive a seasonal influenza vaccination using Protection Motivation Theory. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 233, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Yen, C.-F.; Chang, Y.-P.; Wang, P.-W. Comparisons of Motivation to Receive COVID-19 Vaccination and Related Factors between Frontline Physicians and Nurses and the Public in Taiwan: Applying the Extended Protection Motivation Theory. Vaccines 2021, 9, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Pandemic Fatigue—Reinvigorating the Public to Prevent COVID-19: Policy Framework for Supporting Pandemic Prevention and Management; Contract No.: WHO/EURO:2020-1160-40906-55390; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Okuhara, T.; Okada, H.; Kiuchi, T. Addressing message fatigue for encouraging COVID-19 vaccination. J. Commun. Healthc. 2023, 16, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassen, J.; Nowak, T.J.; Henderson, A.D.; Weaver, S.P.; Baker, E.J.; Muehlenbein, M.P. Longitudinal changes in COVID-19 concern and stress: Pandemic fatigue overrides individual differences in caution. J. Public Health Res. 2022, 11, 22799036221119011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Deng, J.; Du, M.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yan, W.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Pandemic Fatigue and Vaccine Hesitancy among People Who Have Recovered from COVID-19 Infection in the Post-Pandemic Era: Cross-Sectional Study in China. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, D.D.; Bader, M.; Betsch, C.; Böhm, R.; Lilleholt, L.; Sprengholz, P.; Zettler, I. The moderating role of trust in pandemic-relevant institutions on the relation between pandemic fatigue and vaccination intentions. J. Health Psychol. 2024, 29, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Katsoulas, T.; Kaitelidou, D. Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Intention among Nurses Who Have Been Fully Vaccinated against COVID-19: Evidence from Greece. Vaccines 2023, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.; Purvis, R.; Hallgren, E.; Willis, D.; Hall, S.; Reece, S.; CarlLee, S.; Judkins, H.; McElfish, P. Motivations to Vaccinate Among Hesitant Adopters of the COVID-19 Vaccine. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.; Luminet, O.; Klein, O.; Morbée, S.; Van den Bergh, O.; Van Oost, P.; Waterschoot, J.; Yzerbyt, V.; Vansteenkiste, M. Predicting vaccine uptake during COVID-19 crisis: A motivational approach. Vaccine 2022, 40, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.A.; Morse, B.S.; Tsai, L.L. Public health and public trust: Survey evidence from the Ebola Virus Disease epidemic in Liberia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 172, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinck, P.; Pham, P.N.; Bindu, K.K.; Bedford, J.; Nilles, E.J. Institutional trust and misinformation in the response to the 2018-19 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu, DR Congo: A population-based survey. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadeddu, C.; Regazzi, L.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Rosano, A.; Unim, B.; Griebler, R.; Link, T.; De Castro, P.; D’Elia, R.; Mastrilli, V.; et al. The Determinants of Vaccine Literacy in the Italian Population: Results from the Health Literacy Survey 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collini, F.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Del Riccio, M.; Bruschi, M.; Forni, S.; Galletti, G.; Gemmi, F.; Ierardi, F.; Lorini, C. Does Vaccine Confidence Mediate the Relationship between Vaccine Literacy and Influenza Vaccination? Exploring Determinants of Vaccination among Staff Members of Nursing Homes in Tuscany, Italy, during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Chu, H. Examining the direct and indirect effects of trust in motivating COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 2096–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Managers (n = 10) | Staff (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 6 (75%) | 7 (70%) |

| Missing data | 2 | 1 | |

| Characteristics | Managers (n = 13) | Staff (n = 18) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 13 (100%) | 16 (88.9%) |

| Age range | 20–29 | 0 | 1 |

| 30–39 | 0 | 3 | |

| 40–49 | 5 | 5 | |

| 50–59 | 3 | 8 | |

| 60–69 | 2 | 1 | |

| Missing data | 3 | 0 | |

| Ethnicity | White British | 8 | 16 |

| White other | 2 | 1 | |

| South Asian | 0 | 1 | |

| Missing data | 1 | 0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anyiam-Osigwe, A.; Katangwe-Chigamba, T.; Scott, S.; Seeley, C.; Patel, A.; Sims, E.J.; Holland, R.; Bion, V.; Clark, A.B.; Griffiths, A.W.; et al. A Psychosocial Critique of the Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on UK Care Home Staff Attitudes to the Flu Vaccination: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12121437

Anyiam-Osigwe A, Katangwe-Chigamba T, Scott S, Seeley C, Patel A, Sims EJ, Holland R, Bion V, Clark AB, Griffiths AW, et al. A Psychosocial Critique of the Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on UK Care Home Staff Attitudes to the Flu Vaccination: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study. Vaccines. 2024; 12(12):1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12121437

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnyiam-Osigwe, Adaku, Thando Katangwe-Chigamba, Sion Scott, Carys Seeley, Amrish Patel, Erika J. Sims, Richard Holland, Veronica Bion, Allan B. Clark, Alys Wyn Griffiths, and et al. 2024. "A Psychosocial Critique of the Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on UK Care Home Staff Attitudes to the Flu Vaccination: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study" Vaccines 12, no. 12: 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12121437

APA StyleAnyiam-Osigwe, A., Katangwe-Chigamba, T., Scott, S., Seeley, C., Patel, A., Sims, E. J., Holland, R., Bion, V., Clark, A. B., Griffiths, A. W., Jones, L., Wagner, A. P., Wright, D. J., & Birt, L. (2024). A Psychosocial Critique of the Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on UK Care Home Staff Attitudes to the Flu Vaccination: A Qualitative Longitudinal Study. Vaccines, 12(12), 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines12121437