Childhood Vaccine Attitude and Refusal among Turkish Parents

Abstract

1. Introduction

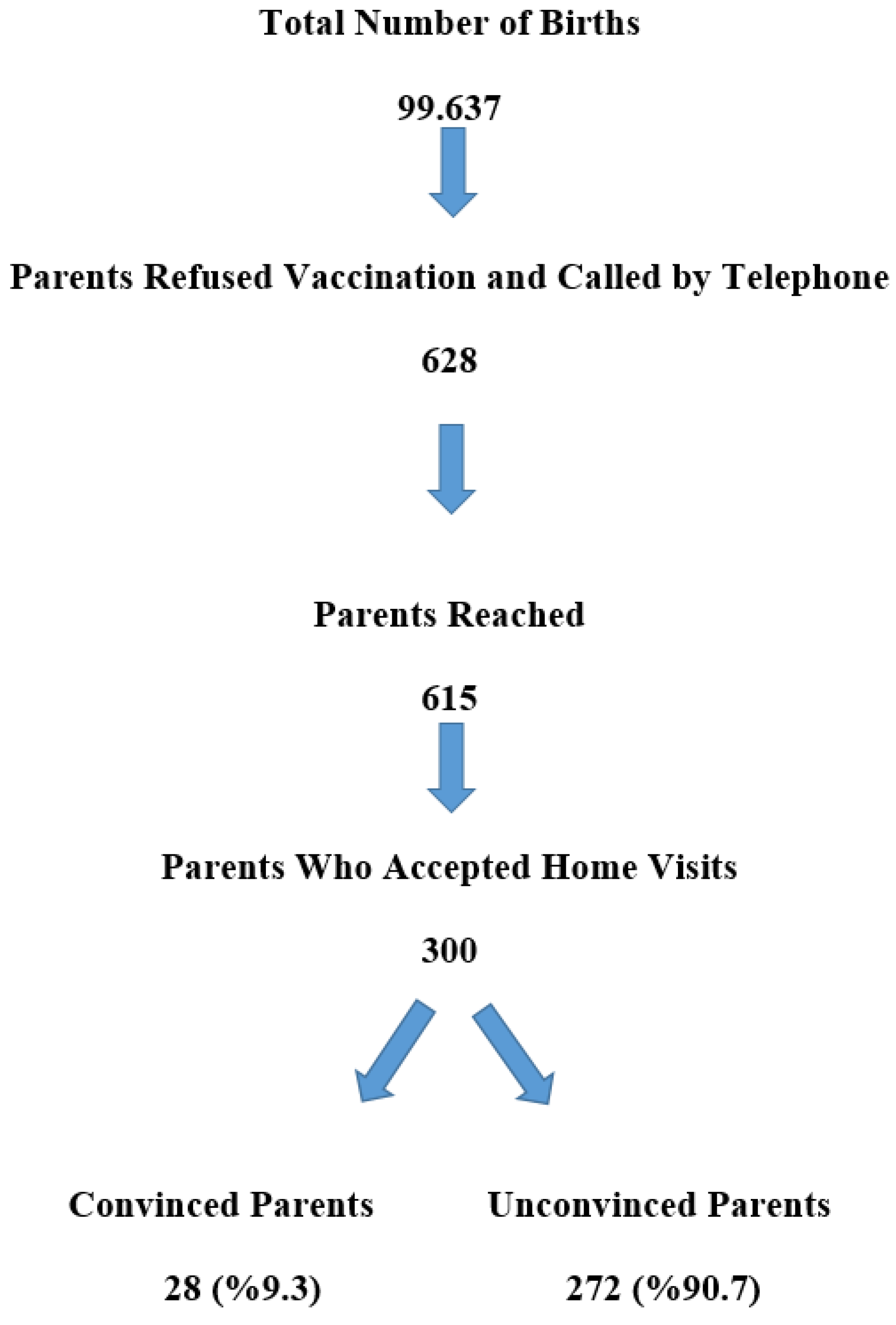

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Location

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Study Instrument

2.4. Ethics

2.5. Statistical Analysis

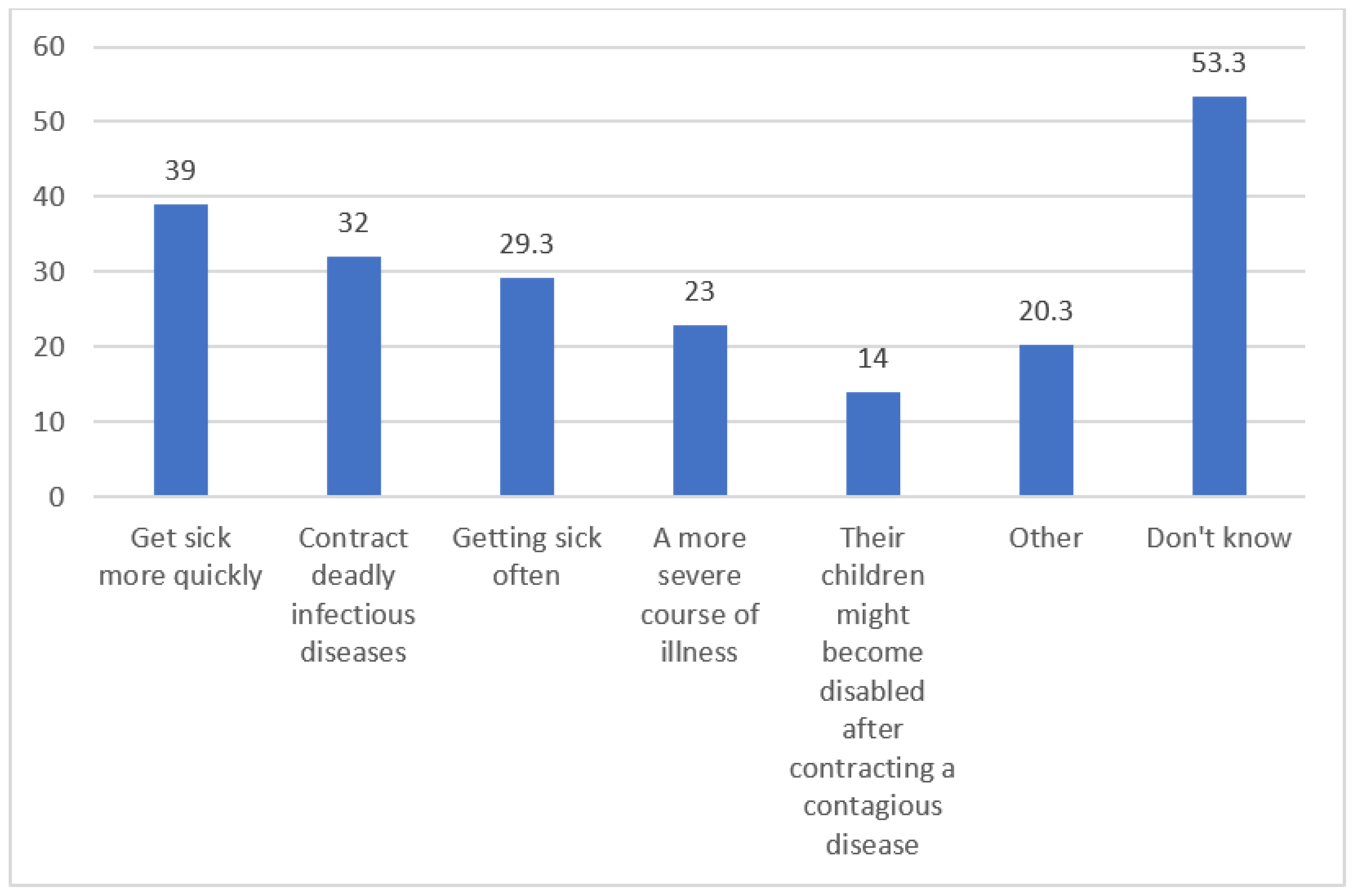

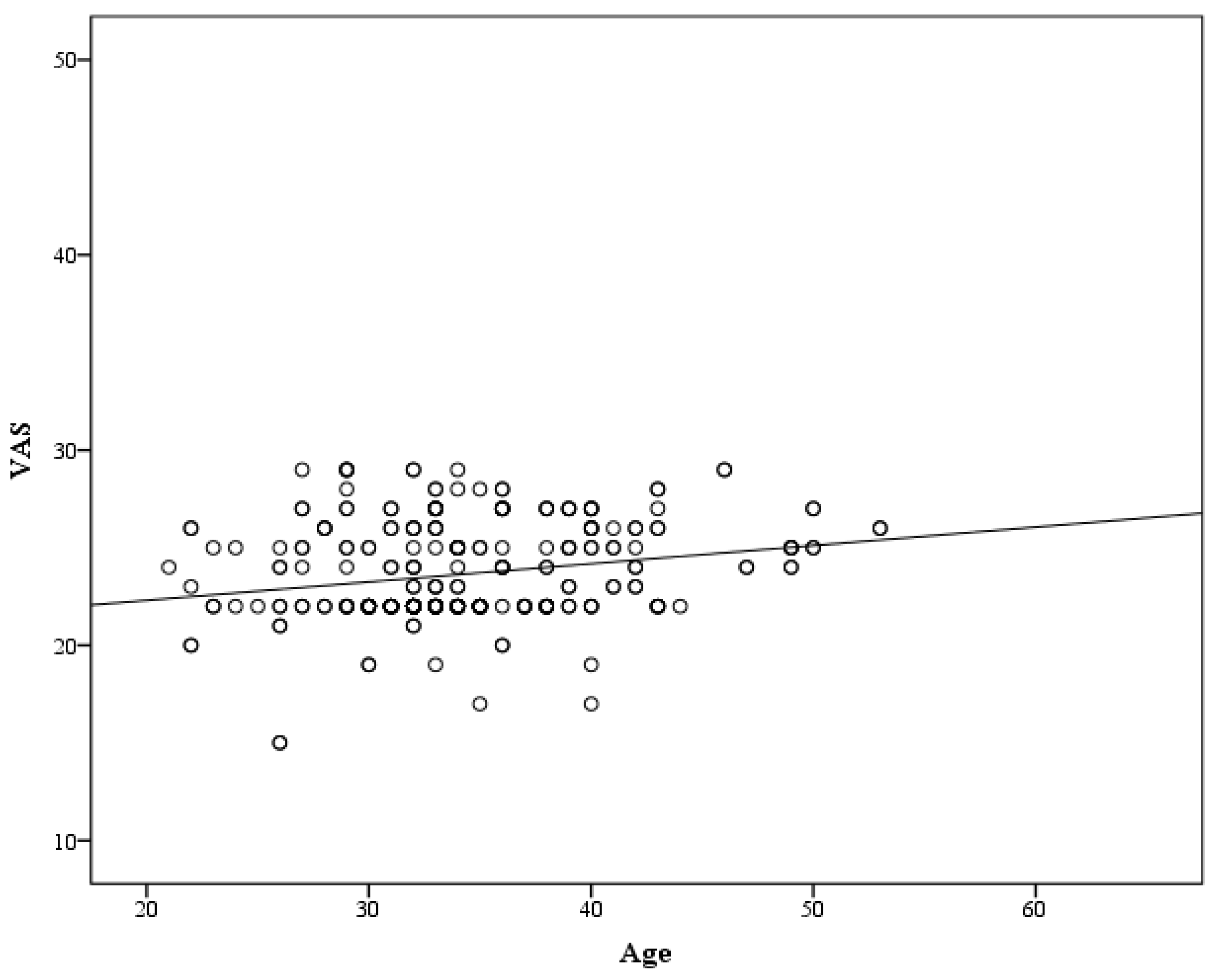

3. Results

4. Discussion

- -

- Safety concerns: Some parents express concerns about the safety of vaccines and their potential side effects [14].

- -

- Lack of need: Some parents may not see the need for vaccines or believe that their child is not at risk for vaccine-preventable diseases [19].

- -

- Negative media information: Exposure to negative information about vaccines through social media or other sources can contribute to vaccine hesitancy [20].

- -

- Fear of adverse events: Some parents may be hesitant to vaccinate their child due to the fear of adverse events following immunization (AEFIs) [21].

- -

- Time constraints: Parents may have difficulty finding time to take their child for vaccinations due to work schedules or other commitments [13].

- -

- Special physical conditions: Some parents may believe that their child’s physical condition is not suitable for vaccination [13].

- -

- Beliefs about risk: Some parents may believe that their child is not at risk for vaccine-preventable diseases or that the risk of severe illness from the disease is low [13].

- -

- Medical mistrust: Some parents may have a general mistrust of medical establishments or healthcare providers [22].

- -

- Cultural or religious beliefs: Some parents may have cultural or religious beliefs that conflict with vaccination [23].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nguyen, K.H.; Srivastav, A.; Lindley, M.C.; Fisher, A.; Kim, D.; Greby, S.M.; Lee, J.; Singleton, J.A. Parental vaccine hesitancy and association with childhood diphtheria, tetanus toxoid, and acellular pertussis; measles, mumps, and rubella; rotavirus; and combined 7-series vaccination. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2022, 62, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokce, A.; Ozdemir, A.T.; Boz, G.; Aslan, M.; Ozer, A. The knowledge and behaviours of the healthcare staff regarding vaccine rejection. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, ckaa166.1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Mack, W.J.; Neely, M.; Lewis, L.; Anand, V. Parental perspectives on immunizations: Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on childhood vaccine hesitancy. J. Community Health 2022, 1, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, L.; Li, B.; Lu, Y. Association between adult vaccine hesitancy and parental acceptance of childhood COVID-19 vaccines: A web-based survey in a northwestern region in China. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, E. Aşı kararsızlığı. In Asılar, 1st ed.; Türkiye Klinikleri: Ankara, Turkey, 2021; pp. 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Salali, G.; Uysal, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Is Associated with Beliefs on the Origin of The Novel Coronavirus In The UK and Turkey. Psychol. Med. 2020, 15, 3750–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendau, A.; Plag, J.; Petzold, M.; Ströhle, A. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Related Fears and Anxiety. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 97, 107724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, Y.; Yalman, F. The Effect of Health Professionals’ Attitudes Towards COVID-19 Vaccines on Hesitance Situations: The Mediator Role of Vaccine Confidence. Afet Ve Risk Dergisi. 2023, 1, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.; Sahin, M.; Parildar, H.; Güvenç, I. The Willingness to Accept the COVID-19 Vaccine and Affecting Factors Among Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-sectional Study in Turkey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçu, S.; Almış, H.; Başkan, S.; Turgut, M.; Orhon, F.Ş.; Ulukol, B. Evaluation of childhood vaccine refusal and hesitancy intentions in Turkey. Indian J. Pediatr. 2019, 86, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.S.; Wannemuehler, K.; Bonsu, G.; Wardle, M.; Nyaku, M.; Amponsah-Achiano, K.; Dadzie, J.F.; Sarpong, F.O.; Orenstein, W.A.; Rosenberg, E.S.; et al. Development of a valid and reliable scale to assess parents’ beliefs and attitudes about childhood vaccines and their association with vaccination uptake and delay in Ghana. Vaccine 2019, 37, 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, S.S.; Erdoğan, Ç.; Turan, T.; Ergin, A.; Akçay, G. Aşı Tutumları Ölçeğinin Türkçe Formunun Geçerlilik ve Güvenirliliği. Türkiye Klin. Pediatri Derg. 2021, 30, 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Xu, D.; Luo, L.; Ma, F.; Wang, P.; Li, H.; Wei, L.; Diao, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. A cross-sectional survey on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among parents from Shandong vs. Zhejiang. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 779720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, T.; Pandit, R.; Goyal, L. Uncommon Side Effects of COVID-19 Vaccination in the Pediatric Population. Cureus 2022, 14, e30276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pippert, C.H.; Lin, J.; Lazer, D.; Perlis, R.; Simonson, M.D.; Ognyanova, K.; Druckman, J.; Tandon, U.; Baum, M.A.; Santillana, M. The COVID States Project# 61: Parental Concerns About COVID-19 Vaccines. osfpreprints 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Miraglia del Giudice, G.; Angelillo, S.; Fattore, I.; Licata, F.; Pelullo, C.P.; Di Giuseppe, G. Hesitancy towards childhood vaccinations among parents of children with underlying chronic medical conditions in Italy. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijjambu, A.; Mulogo, E.M. Determinants of Hesitancy to Childhood Immunizations in a Peri-Urban Settlement; A Case Study of Nansana Municipality, Uganda. TIJPH 2013, 3, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, A.; Saville, A.W.; Albertin, C.; Zimet, G.; Breck, A.; Helmkamp, L.; Vangala, S.; Dickinson, L.M.; Rand, C.; Szilagyi, P.G. Parental hesitancy about routine childhood and influenza vaccinations: A national survey. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20200961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghasham, Y.A.; Al-Feraidi, A.D. Perception regarding routine childhood vaccinations: A cross-sectional study in Al-Qassim married population. IJMDC 2023, 7, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, N.; Suman, M.; Ersoy, M.; Örün, E. Parents’ Attitudes toward Childhood Vaccines and COVID-19 Vaccines in a Turkish Pediatric Outpatient Population. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erchick, D.J.; Gupta, M.; Blunt, M.; Bansal, A.; Sauer, M.; Gerste, A.; Holroyd, T.A.; Wahl, B.; Santosham, M.; Limaye, R.J. Understanding determinants of vaccine hesitancy and acceptance in India: A qualitative study of government officials and civil society stakeholders. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, C.; Bohannon, K. Exploring the reasons behind parental refusal of vaccines. J. Pediatr. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 21, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soysal, G.; Akdur, R. Investigating Vaccine Hesitancy and Refusal Among Parents of Children Under Five: A Community-based Study. J. Curr. Pediatr. 2022, 20, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skitarelić, N.; Vidaić, M.; Skitarelić, N. Parents’ versus Grandparents’ Attitudes about Childhood Vaccination. Children 2022, 9, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şen, M.; AKIN, B.; Özaydin, T. The Attitudes of Undergraduate Nursing Students to Childhood Vaccines. J. Contemp. Med. 2022, 3, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Gu, W.; Xie, H.; Wang, X.; Cao, L.; Shan, M.; Wu, P.; Tian, Y.; Zhou, K. Parental Attitudes Towards Vaccination Against COVID-19 In China During Pandemic. IDR 2022, 15, 4541–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loncarevic, G.; Jovanovic, A.; Kanazir, M.; Tepavcevic, D.; Maric, G.; Pekmezovic, T. Are Pediatricians Responsible for Maintaining High Mmr Vaccination Coverage? Nationwide Survey on Parental Knowledge and Attitudes Towards Mmr Vaccine in Serbia. PLoS ONE 2023, 2, e0281495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedin, M.; Islam, M.; Rahman, F.; Reza, H.; Hossain, M.; Hossain, M.; Arefin, A.; Hossain, A. Willingness to Vaccinate Against COVID-19 Among Bangladeshi Adults: Understanding the Strategies to Optimize Vaccination Coverage. PLoS ONE 2021, 4, e0250495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamara, F.; Fajar, J.; Soegiarto, G.; Wulandari, L.; Kusuma, A.; Pasaribu, E.; Putra, R.P.; Rizky, M.; Anshor, T.; Harapan, H.; et al. The Refusal of COVID-19 Vaccination and Its Associated Factors: A Systematic Review. F1000Research 2023, 12, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, M.; Ms, K.; Mughal, A.; Tariq, A.; Yaseen, M.; Fayyaz, T. Effectiveness of Health Education Message in Improving Tetanus Health Literacy Among Women of Childbearing Age: A Quasi-experimental Study. JRMC 2020, 1, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, P.; Rauber, D.; Betsch, C.; Lidolt, G.; Denker, M. Barriers of Influenza Vaccination Intention and Behavior—A Systematic Review of Influenza Vaccine Hesitancy, 2005–2016. PLoS ONE 2017, 1, e0170550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, N.; Chapman, G.; Rothman, A.; Leask, J.; Kempe, A. Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science into Action. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2017, 3, 149–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.; Loe, B.; Yu, L.; Freeman, J.; Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C.; Shanyinde, M.; Harris, V.; Waite, F.; Lambe, S.; et al. Effects of Different Types of Written Vaccination Information on COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy In the Uk (Oceans-iii): A Single-blind, Parallel-group, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e416–e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, A.; Denman, D.; Sala, M.; Marks, E.; Shay, L.; Fuller, S.; Persaud, D.; Lee, S.C.; Skinner, C.S.; Tiro, J.; et al. Translating Self-persuasion Into an Adolescent Hpv Vaccine Promotion Intervention for Parents Attending Safety-net Clinics. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 4, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyris, Y.; Monu, K.; Tan, P.; Aarts, C.; Jiang, F.; Wiseley, K. Using Machine Learning to Compare Provaccine and Antivaccine Discourse Among the Public on Social Media: Algorithm Development Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 6, e23105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Cheng, P.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X. Hpv Vaccine Hesitancy Among Medical Students in China: A Multicenter Survey. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 774767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellithorpe, M.; Adams, R.; Aladé, F. Parents’ Behaviors and Experiences Associated with Four Vaccination Behavior Groups for Childhood Vaccine Hesitancy. Matern. Child Health J. 2022, 2, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raof, A. Parental Attitude and Beliefs Towards Child Vaccination: Identifying Vaccine Hesitant Groups in A Family Health Center, Erbil City, Iraq. ME-JFM 2018, 6, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallas, D.; Altman, S.; Mandel, E.; Fletcher, J. Vaccine Hesitancy in Prenatal Women and Mothers of Newborns. Nurse Pract. 2023, 3, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitaresmi, M.N.; Rozanti, N.M.; Simangunsong, L.B.; Wahab, A. Improvement of Parent’s Awareness, Knowledge, Perception, and Acceptability of HPV Vaccination After an Educational Intervention. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesiama, E.; Vopni, R.; Fuentes, N.; Prabhu, F.; Bennett, K. Assessing and Addressing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in A West Texas Free Clinic Through Motivational Interview-guided Intervention. Chronicles 2022, 45, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, J.; Kinnersley, P.; Jackson, C.; Cheater, F.; Bedford, H.; Rowles, G. Communicating with parents about vaccination: A framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomares, T.D.; Buttenheim, A.M.; Amin, A.B.; Joyce, C.M.; Porter, R.M.; Bednarczyk, R.A.; Omer, S.B. Association of cognitive biases with human papillomavirus vaccine hesitancy: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nia, H.S.; Allen, K.A.; Arslan, G.; Kaur, H.; She, L.; Fomani, F.K.; Gorgulu, O.; Froelicher, E.S. The predictive role of parental attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines and child vulnerability: A multi-country study on the relationship between parental vaccine hesitancy and financial well-being. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1085197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, R.; Aitken, D.; Freedman, J.L.; Einstein, G. Mistrust of the medical profession and higher disgust sensitivity predict parental vaccine hesitancy. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean ± SD | 34.2 ± 5.8 | ||

| Interviewed person | Father | 52 | 17.3 |

| Mother | 248 | 82.7 | |

| Educational status | Primary/secondary school | 24 | 8.0 |

| High School | 154 | 51.3 | |

| University | 122 | 40.7 | |

| Profession | Homemaker | 180 | 60.0 |

| Teacher | 36 | 12.0 | |

| Government employee | 43 | 14.3 | |

| Healthcare profession | 14 | 4.7 | |

| Artisan | 16 | 5.3 | |

| Other | 11 | 3.7 | |

| Number of Children | 1 | 42 | 14.0 |

| 2 | 107 | 35.7 | |

| 3 and above | 151 | 50.3 | |

| Presence of children under one-year-old | Yes | 51 | 17.0 |

| No | 249 | 83.0 | |

| Opinion on necessity of the vaccine | Yes | 37 | 12.3 |

| No | 249 | 83.0 | |

| Indecisive | 14 | 4.7 | |

| Having a child vaccinated previously. | Yes | 264 | 88.0 |

| No | 36 | 12.0 | |

| Having problems with vaccination before | Yes | 110 | 41.7 |

| No | 154 | 58.3 | |

| Status of getting the vaccines recommended by the Ministry | Has gotten some vaccines | 224 | 74.7 |

| Has not gotten any vaccines | 76 | 25.3 | |

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| I do not think vaccines are safe/I am worried about the side effects | 297 | 99.0 |

| I think it is not necessary | 215 | 71.7 |

| I do not think vaccines are effective in protecting from diseases | 183 | 61.0 |

| Chemical substances in vaccines are harmful to human health. | 151 | 50.3 |

| Someone else said that their child had a bad reaction after vaccination. | 133 | 44.3 |

| Negative things about the vaccine I read or heard from the media | 110 | 36.7 |

| Bad experiences with healthcare professionals or healthcare provider | 71 | 23.7 |

| Religious reasons | 24 | 8.0 |

| Those Who Are Convinced | p * | VAS | p ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Mean ± SD | ||||

| Interviewed person | Father | 9 | 17.3 | 0.038 | 24.3 ± 3.5 | 0.007 |

| Mother | 19 | 7.7 | 23.5 ± 2.1 | |||

| Educational status | Primary/secondary school | 6 | 25.0 a | 0.02 | 23.5 ± 2.5 | 0.258 |

| High School | 11 | 7.1 b | 23.5 ± 2.1 | |||

| University | 11 | 9.0 b | 23.8 ± 2.8 | |||

| Profession | Homemaker | 19 | 10.6 | 0.745 | 23.0 ± 2.0 a | <0.001 |

| Teacher | 3 | 8.3 | 25.0 ± 2.6 b | |||

| Government employee | 4 | 9.3 | 24.2 ± 2.5 b | |||

| Healthcare profession | 2 | 14.3 | 24.2 ± 4.5 b | |||

| Artisan | 0 | 0.0 | 24.4 ± 2.1 b | |||

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | 26.1 ± 1.8 b | |||

| Number of Children | 1 | 8 | 19.0 a | 0.024 | 23.5 ± 1.7 | 0.480 |

| 2 | 5 | 4.7 b | 23.9 ± 2.7 | |||

| 3 and above | 15 | 9.9 ab | 23.5 ± 2.4 | |||

| Presence of children under one-year-old | Yes | 9 | 17.6 | 0.034 | 24.0 ± 3.1 | 0.280 |

| No | 19 | 7.6 | 23.6 ± 2.3 | |||

| Perception on necessity of the vaccine | Yes | 8 | 21.6 a | 0.031 | 23.4 ± 3.0 | 0.128 |

| No | 19 | 7.6 b | 23.6 ± 2.3 | |||

| Indecisive | 1 | 7.1 b | 24.5 ± 2.8 | |||

| Having a child vaccinated previously. | Yes | 26 | 9.8 | 0.551 | 23.7 ± 2.5 | 0.202 |

| No | 2 | 5.6 | 23.2 ± 1.7 | |||

| Having problems with vaccination before | Yes | 5 | 4.5 | 0.015 | 23.7 ± 2.4 | 0.937 |

| No | 21 | 13.6 | 23.7 ± 2.7 | |||

| Is there any side effect? | Yes | 19 | 7.1 a | <0.001 | 23.8 ± 2.3 a | 0.044 |

| No | 8 | 44.4 b | 21.8 ± 3.4 b | |||

| I do not know | 1 | 6.7 a | 22.9 ± 2.2 ab | |||

| Status of getting the vaccines recommended by the Ministry | Has gotten some vaccines | 26 | 11.6 | 0.02 | 23.7 ± 2.5 | 0.320 |

| Has not gotten any vaccines | 2 | 2.6 | 23.5 ± 2.4 | |||

| Those Who Are Convinced | Those Who Are Not Convinced | p * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| VAS | 20.7 ± 2.2 | 23.9 ± 2.3 | <0.001 |

| Age | 31.4 ± 5.3 | 34.5 ± 5.8 | 0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurt, O.; Küçükkelepçe, O.; Öz, E.; Doğan Tiryaki, H.; Parlak, M.E. Childhood Vaccine Attitude and Refusal among Turkish Parents. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081285

Kurt O, Küçükkelepçe O, Öz E, Doğan Tiryaki H, Parlak ME. Childhood Vaccine Attitude and Refusal among Turkish Parents. Vaccines. 2023; 11(8):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081285

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurt, Osman, Osman Küçükkelepçe, Erdoğan Öz, Hülya Doğan Tiryaki, and Mehmet Emin Parlak. 2023. "Childhood Vaccine Attitude and Refusal among Turkish Parents" Vaccines 11, no. 8: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081285

APA StyleKurt, O., Küçükkelepçe, O., Öz, E., Doğan Tiryaki, H., & Parlak, M. E. (2023). Childhood Vaccine Attitude and Refusal among Turkish Parents. Vaccines, 11(8), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11081285