EU Member States’ Institutional Twitter Campaigns on COVID-19 Vaccination: Analyses of Germany, Spain, France and Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Political and Institutional Communication 2.0

1.2. Digital Communication on Twitter

1.3. Pandemic and Vaccination Institutional Strategies Management

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objectives and Hypotheses

O1. Observe the level of interaction (one-way or two-way) between prime ministers, health ministers, governments and health ministries and users on Twitter, measuring the degree of commitment or engagement through retweets, likes and comments.

O2. Study the use that these politicians and institutions make of Twitter’s discursive resources (images, videos, links, etc.).

O3. Identify whether vaccination constituted the thematic agenda raised by the official profiles of the selected politicians and institutions and, if so, assess to what extent.

O4. Examine the sentiments attached to the vaccine messages of these politicians and institutions.

H1. In the digital interactions (about vaccination) of politicians and institutions with citizens, uni-directionality prevails over bi-directionality. Therefore, politicians and institutions consolidate the use of Twitter as part of their vaccination communication strategy. Both participate actively and exploit the resources offered by the tool, such as the inclusion of images or links that redirect to the corporate website for further information.

H2. The main content of the messages focuses on issues related to the political and institutional agenda, leaving vaccine-related issues in the background.

H3. The messages published by the European institutions and leading European officials do not present an accentuated positive polarity of a hopeful nature.

H4. The contents of publications related to the vaccine tend to generate more engagement than those that differ from the vaccine.

2.2. Methodology

3. Results

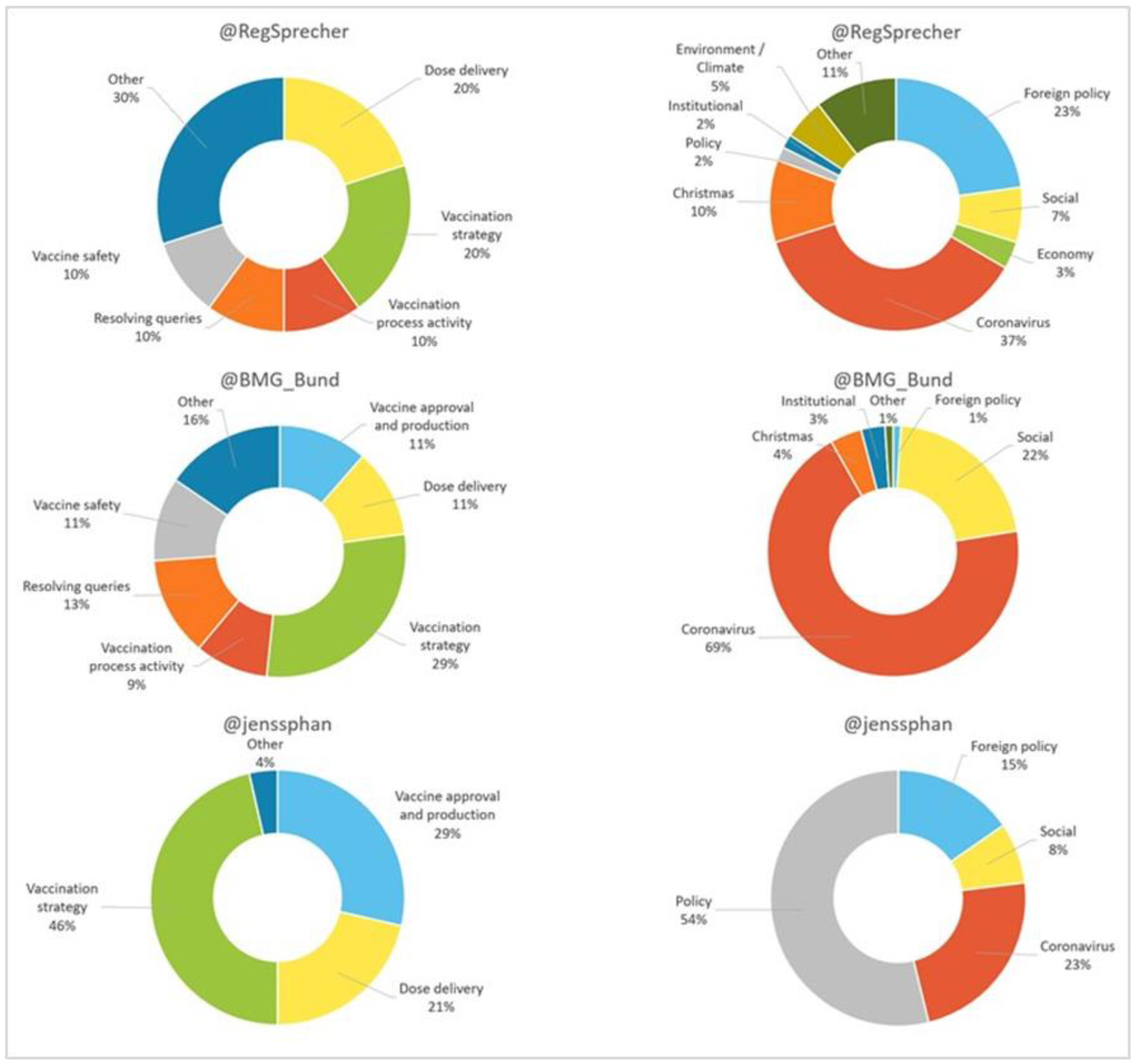

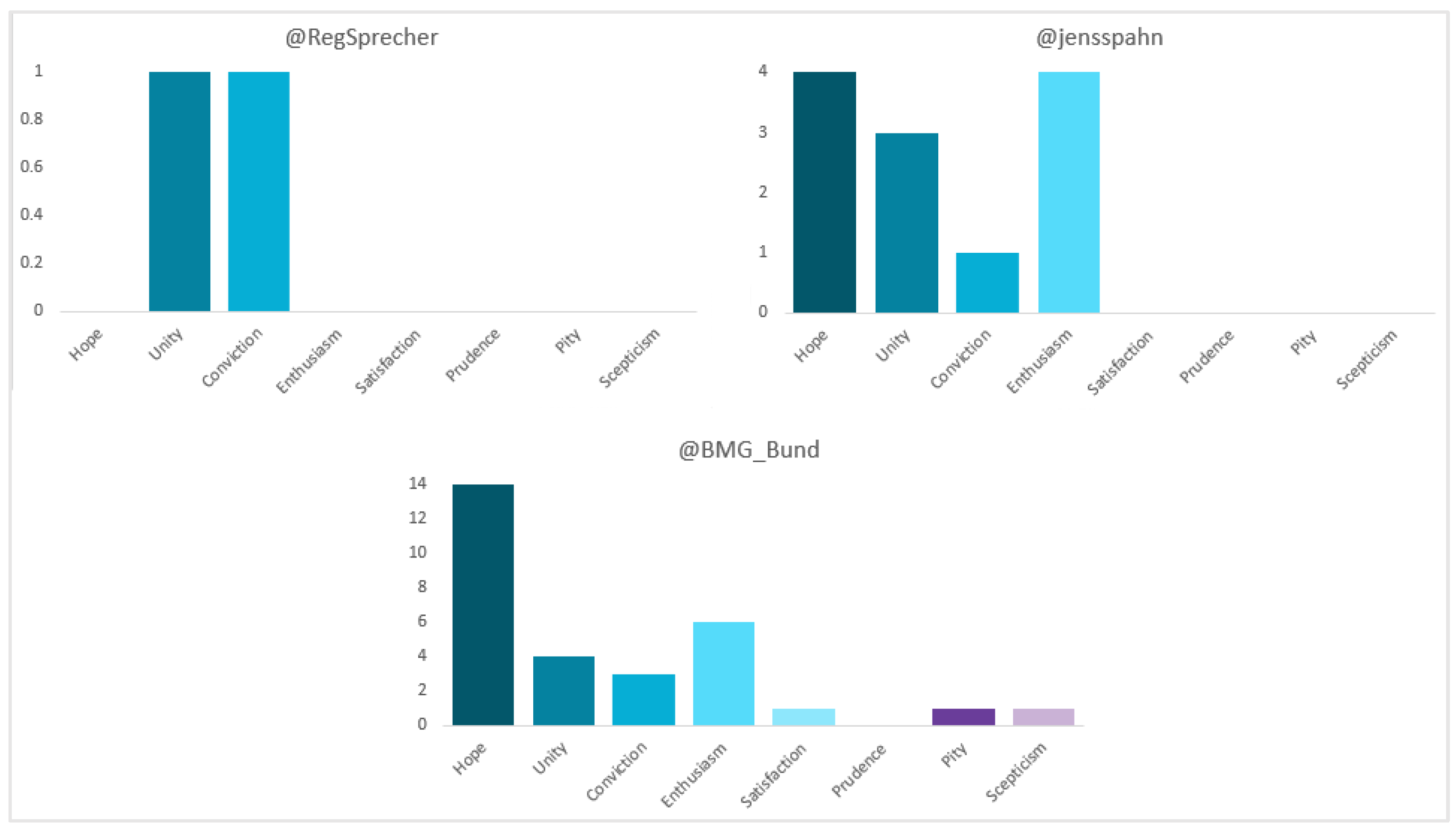

3.1. Case Study: Germany

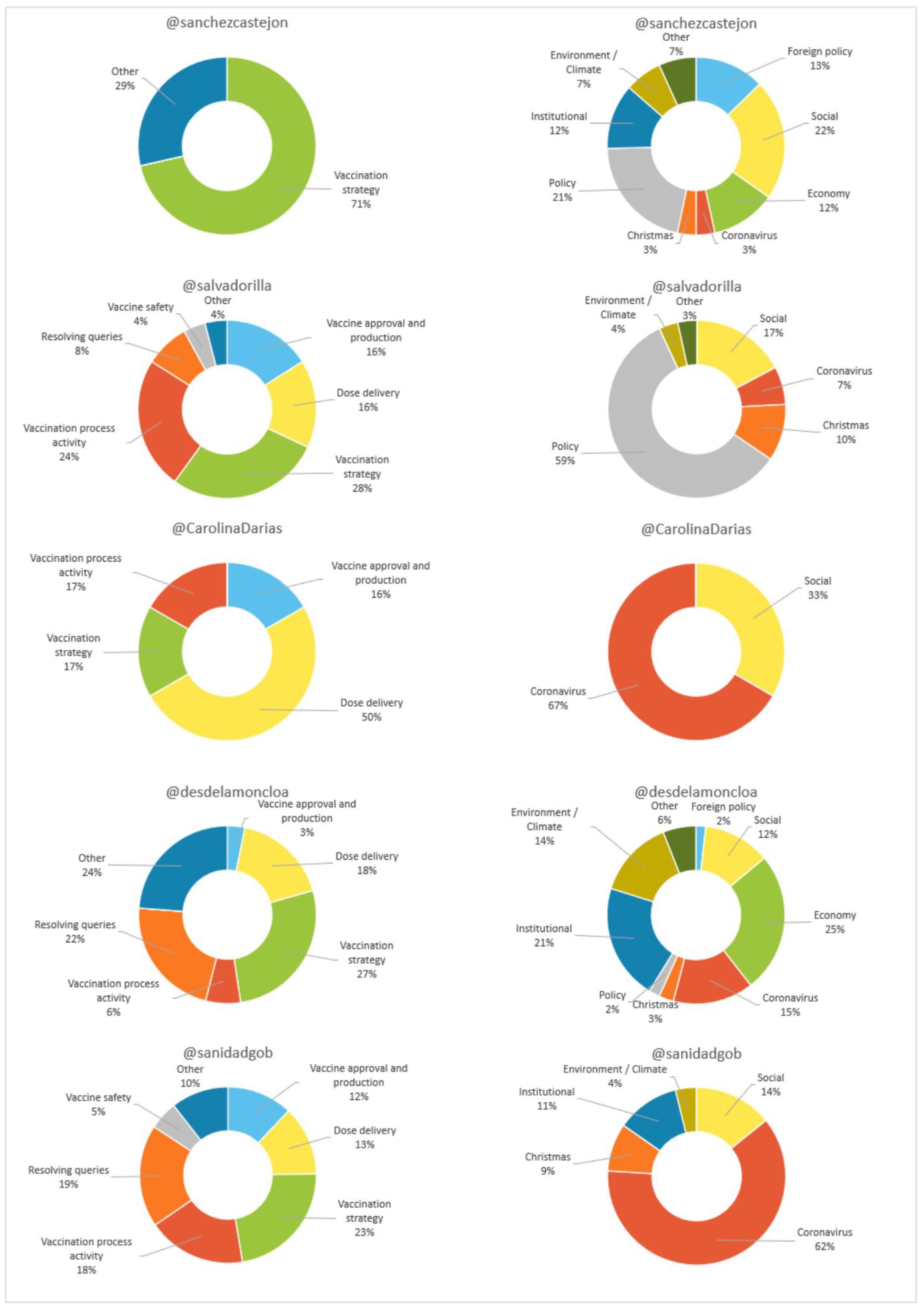

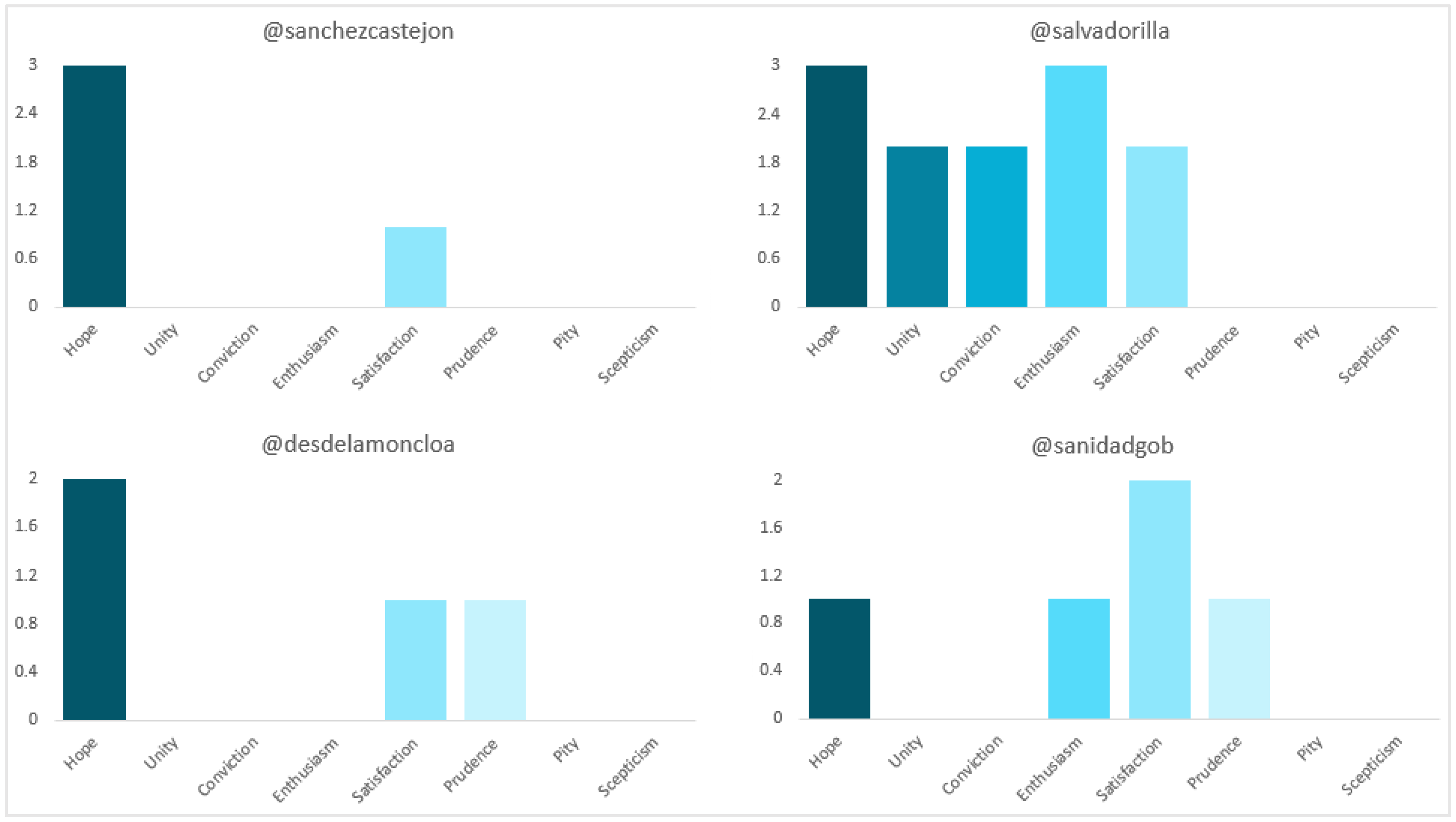

3.2. Case Study: Spain

3.3. Case Study: France

3.4. Case Study: Italy

4. Discussion and Conclusions

H1. stated that, in the digital interactions of politicians and institutions with citizens, uni-directionality prevails over bi-directionality, and therefore they consolidated the use of Twitter as part of their communication strategy.

H2. stated that the main content of the messages focuses on issues related to the political and institutional agenda, leaving vaccine-related issues in the background.

H3. argued that the messages published by the European institutions and leading European officials do not present an accentuated positive polarity of a hopeful nature.

H4. stated that the contents of publications related to the vaccine tend to generate more engagement than those that differ from the vaccine.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Content | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category of Analysis | |

| Type | 1. Tweet | |

| 2. Mention | ||

| 3. Response/reply | ||

| Format | 1. Text | |

| 2. Image (photograph, infographics and animated GIFs) | ||

| 3. Video | ||

| 4. Link to external website/other networks | ||

| 5. Link to media | ||

| 6. Other tweet | ||

| Content | 0. No mention of the vaccine | 1. Foreign policy (Brexit, China, USA, etc.) |

| 2. Social (education, feminism, health, etc.) | ||

| 3. Economy (agriculture, employment, tourism, etc.) | ||

| 4. Coronavirus | ||

| 5. Christmas | ||

| 6. Policy | ||

| 7. Institutional (agenda events, visits to venues) | ||

| 8. Environment/climate | ||

| 9. Other (science, culture, sport, etc.) | ||

| 1. Talk about the vaccine | 1. Vaccine approval and production | |

| 2. Delivery of doses | ||

| 3. Vaccination strategy | ||

| 4. Vaccination process activity | ||

| 5. Resolution of doubts | ||

| 6. Vaccine safety | ||

| 7. Other | ||

| Sentiment | ||

| Variable | Category of analysis | |

| Polarity | 1. Positive | 1. Hope |

| 2. Unity | ||

| 3. Conviction | ||

| 4. Enthusiasm | ||

| 5. Satisfaction | ||

| 6. Prudence | ||

| 2. Negative | 1. Pity | |

| 2. Scepticism | ||

| 3. Neutral | ||

Appendix B

| Retweet | ‘Likes’ | Commentaries | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1.913 | 1.913 | 1.913 | |

| Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P E R C E N T I L | 10 | 10 | 25 | 3 |

| 20 | 18 | 36 | 6 | |

| 30 | 25 | 49 | 10 | |

| 40 | 34 | 68 | 16 | |

| 50 | 47 | 103 | 27 | |

| 60 | 72 | 169 | 48 | |

| 70 | 116 | 329 | 97 | |

| 80 | 196 | 742 | 207 | |

| 90 | 420 | 1.891 | 492 | |

| Maximum | 15.700 | 86.400 | 8.800 | |

References

- Dubé, E.; Laberge, C.; Guay, M.; Bramadat, P.; Roy, R.; Bettinger, J.A. Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consuegra, M. El movimiento antivacunas: Un aliado de la COVID-19. Rev. Int. De Pensam. Político 2021, 15, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Diez Cuestiones de Salud Que la OMS Abordará Este Año. OMS. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Larson, H.J. The biggest pandemic risk? Viral misinformation. Nature 2018, 562, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, N.; Coomes, E.A.; Haghbayan, H.; Gunaratne, K. Social media and vaccine hesitancy: New updates for the era of COVID-19 and globalized infectious diseases. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2586–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rufai, S.R.; Bunce, C. World leaders’ usage of Twitter in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A content analysis. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castells, M. La Sociedad Red: Una Visión Global; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- We Are Social and Hootsuite. (January, 2021). Digital 2021: Global Digital Overview. We Are Social. Available online: https://wearesocial.com/digital-2021 (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- O’Reilly, T. What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. 2005. Available online: https://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Holtz, C. Web 2.0: Nuevos Desafíos en Comunicación Política. Diálogo Político 2013, 30, 11–27. Available online: https://www.kas.de/documents/252038/253252/7_dokument_dok_pdf_34654_4.pdf/b0a1db76-a257-ed22-6420-6349f41a3720?version=1.0&t=1539655632653 (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Rodríguez, R.; Ureña, D. Diez Razones Para el uso de Twitter Como Herramienta en la Comunicación Política y Electoral. Comun. Y Plur. 2021, 10, 89–116. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/50605323.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Cancelo, M.; Almansa, A. Estrategias comunicativas en redes sociales. Estudio comparativo entre las universidades de España y México. Hist. Y Comun. Soc. 2014, 18, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergeer, M. Twitter and political campaigning. Sociol. Compass 2015, 9, 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, L.; Miquel, S.; Casero, A. Un potencial comunicativo desaprovechado. Twitter como mecanismo generador de diálogo en campaña electoral. Obra Digit. Rev. De Comun. 2016, 11, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, L.M. El uso de Twitter Por Los Partidos Políticos Durante la Campaña del 20D. Sphera Publica 2017, 1, 111–131. Available online: http://sphera.ucam.edu/index.php/sphera-01/article/view/304/275 (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Mancera, A.; Pano, A. El discurso Político en Twitter: Análisis de Mensajes que “Trinan”; Anthropos: Springfield, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, E. Twitter y la comunicación política. El Prof. De La Inf. 2017, 26, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, B. Twitter as method: Using Twitter as a tool to conduct research. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods; Sloan, L., Quan Haase, A., Eds.; SAGE Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Tuñón, J.; Carral, U. Twitter como solución a la comunicación europea. Análisis comparado en Alemania, Reino Unido y España. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2019, 74, 1219–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, J.; Carral, U. Has COVID-19 promoted or discouraged a European Public Sphere? Comparative analysis in Twitter between German, French, Italian and Spanish MEPSs during the pandemic. Commun. Soc. 2021, 34, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmelee, J.H.; Bichard, S.L. Politics and the Twitter Revolution: How Tweets Influence the Relationship between Political Leaders and the Public; Lexington Books: Plymouth, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh, B.; Froio, C. A “Europe des Nations”: Far right imaginative geographies and the politization of cultural crisis on Twitter in Western Europe. J. Eur. Integr. 2020, 42, 715–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Casero, A.; Feenstra, R.A.; Tormey, S. Old and new media logics in an electoral campaign: The case of Podemos and the two-way Street mediatization of politics. Int. J. Press/Politics 2016, 21, 378–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouza, L.; Tuñón, J. Personalización, distribución, impacto y recepción en Twitter del discurso de Macron ante el Parlamento Europeo el 17/04/18. El Prof. De La Inf. 2018, 27, 1239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A. Online all the time? A quantitative assessment of the permanent campaign on Facebook. New Media Soc. 2016, 8, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.; Marcos, S.; Casero, A. What do politicians do on Twitter? Functions and communication strategies in the Spanish electoral campaign of 2016. El Prof. De La Inf. 2017, 26, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainous, J.; Wagner, K.M. Tweeting to Power: The Social Media Revolution in American Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Caldevilla, D. Democracia 2.0: La Política se Introduce en Las Redes Sociales. Pensar la Publicidad. Rev. Int. De Investig. Public. 2010, 3, 31–48. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/PEPU/article/view/PEPU0909220031A (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Andre, F.E.; Booy, R.; Bock, H.L.; Clemens, J.; Datta, S.K.; John, T.J.; Lee, B.W.; Lolekha, S.; Peltola, H.; Ruff, T.A.; et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018, 86, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubé, E.; Vivion, M.; MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: Influence, impact and implications. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2015, 14, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornsey, M.; Harris, E.; Fielding, K. The psychological roots of anti-vaccination attitudes: A 24-nation investigation. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, P.; Nera, K.; Delouvée, S. Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloro-quine: A conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spier, R.E. Perception of risk of vaccine adverse events: A historical perspective. Vaccine 2001, 20, S78–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, G.; Spier, R. Fear, misinformation, and innumerates: How the Wakefield paper, the press, and advocacy groups damaged the public health. Vaccine 2010, 28, 2361–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, M.J. WHO’s Top Health Threats for 2019. JAMA 2019, 321, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A.; Betsch, C.; Quattrociocchi, W. Polarization of the vaccination debate on Facebook. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3606–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Cambra, U.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; Niño-González, J.I. An analysis of pro-vaccine and anti-vaccine information on social networks and the internet: Visual and emotional patterns. Prof. De La Inf. 2019, 28, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rico, C.; González-Esteban, J.; Hernández-Martínez, A. Consumo de información en redes sociales durante la crisis de la COVID-19 en España. Rev. De Comun. Y Salud 2020, 10, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Vidal Alaball, J.; Downing, J.; López, F. COVID-19 and the 5G conspiracy theory: Social network analysis of Twitter data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, H.; Syed, S.; Rezaie, S. The Twitter pandemic: The critical role of Twitter in the dissemination of medical information and misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 22, 418–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuñón, J. Europa Frente al Brexit, el Populismo y la Desinformación Supervivencia en Tiempos de Fake News; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2021; ISBN 978-84-18534-06-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tuñón, J.; Elías, C. Comunicar Europa en tiempos de pandemia sanitaria y desinformativa: Periodismo paneuropeo frente a la crisis. In Europa en Tiempos de Desinformación y Pandemia. Periodismo y Política Paneuropeos Ante la Crisis del COVID-19 y Las Fake News; en Tuñón, J., Bouza, L., Eds.; Comares: Granada, Spain, 2021; ISBN 978-84-1369-063-6. [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi, J.L.; Amado, A.; Waisbord, S. Presidential Twitter in the fase of COVID-19: Between populism and pop politics. Comunicar 2021, 29, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, M.; Hernández, V.; Lozano, A. Uso institucional de Twitter para combatir la infodemia causada por la crisis sanitaria de la COVID-19. El Prof. De La Inf. 2021, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas de Roca, R.; García, M.; Rojas, J.L. Estrategias comunicativas en Twitter y portales institucionales durante la segunda ola de COVID-19: Análisis de los gobiernos de Alemania, España, Portugal y Reino Unido. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2021, 79, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuñón, J.; Bouza, L. Europa en Tiempos de Desinformación y Pandemia. Periodismo y Política Paneuropeos Ante la Crisis del COVID-19 y Las Fake News; Comares: Granada, Spain, 2021; ISBN 978-84-1369-063-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A.W.; Connors, C.; Everly, G.S. COVID-19: Peer Support and Crisis Communication Strategies to Promote Institutional Resilience. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 822–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnevie, E.; Gallegos, A.; Goldbarg, J.; Byrd, B.; Smyser, J. Quantifying the rise of vaccine opposition on Twitter during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Commun. Healthc. 2020, 14, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M.; Kousha, K.; Thelwall, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy on English-language Twitter. El Prof. De La Inf. 2021, 30, e300212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neumann-Böhme, S.; Varghese, N.E.; Sabat, I.; Barros, P.P.; Brouwer, W.; van Exel, J.; Schreyögg, J.; Stargardt, T. Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID19. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 977–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, M.; Eid, M.A.; Falkenbach, M.; Rosenbluth, S.T.; Prieto, P.A.; Brammli-Greenberg, S.; McMeekin, P.; Paolucci, F. An analysis of the COVID-19 vaccination campaigns in France, Israel, Italy and Spain and their impact on health and economic outcomes. Health Policy Technol. 2022, 11, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graeber, D.; Schmidt-Petri, C.; Schröder, C. Attitudes on voluntary and mandatory vaccination against COVID-19: Evidence from Germany. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehrau, V.; Fujarski, S.; Lorenz, H.; Schieb, C.; Blöbaum, B. The Impact of Health Information Exposure and Source Credibility on COVID-19 Vaccination Intention in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, G.; Herold, D.; Klotz, P.-A.; Schäfer, J.T. Efficiency in COVID-19 Vaccination Campaigns—A Comparison across Germany’s Federal States. Vaccines 2021, 9, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambon, M.; Schwarzinger, F. Alla Increasing acceptance of a vaccination program for coronavirus disease 2019 in France: A challenge for one of the world’s most vaccine-hesitant countries. Vaccine 2022, 40, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, M.; Kergall, P. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccination intentions and attitudes in France. Public Health 2021, 198, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbo, C.; Candini, V.; Ferrari, C.; d’Addazio, M.; Calamandrei, G.; Starace, F.; Caserotti, M.; Gavaruzzi, T.; Lotto, L.; Tasso, A.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Italy: Predictors of Acceptance, Fence Sitting and Refusal of the COVID-19 Vaccination. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 873098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucchi, M.; Fattorini, E.; Saracino, B. Public Perception of COVID-19 Vaccination in Italy: The Role of Trust and Experts’ Communication. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benis, A.; Seidmann, A.; Ashkenazi, S. Reasons for Taking the COVID-19 Vaccine by US Social Media Users. Vaccines 2021, 9, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, I.; Ruiz, C.; Jiménez, B.; Romero, C.S.; Benítez de Gracia, E. COVID-19 y Vacunación: Análisis del Papel de Las Instituciones Públicas en la Difusión de Información a Través de Twitter. Rev. Española De Salud Pública 2021, 95, 1–16. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/biblioPublic/publicaciones/recursos_propios/resp/revista_cdrom/VOL95/ORIGINALES/RS95C_202106084.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Arcila, C.; Ortega, F.; Jiménez, J.; Trullenque, S. Análisis supervisado de sentimientos políticos en español: Clasificación en tiempo real de tweets basada en aprendizaje automático. El Prof. De La Inf. 2017, 26, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guix, J. El análisis de contenidos: ¿Qué nos están diciendo? Rev. De Calid. Asist. 2008, 23, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M. Sentiment analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods; Sloan, L., Quan haase, A., Eds.; SAGE Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 545–557. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Otero, J.M.; Lagares Diez, N.; Jaráiz Gulías, E.; López-López, P.C. Emociones y Engagement en Los Mensajes Digitales de Los Candidatos a Las Elecciones Generales de 2019; Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación, 2021; Volume XXVI, pp. 229–245. ISSN 1697-7750 · E-ISSN 2340-498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moret Soler, D.; Alonso-Muñoz, L.; Casero-Ripollés, A. La Negatividad Digital Como Estrategia de Campaña en Las Elecciones de la Comunidad de Madrid de 2021 en Twitter. Rev. Prism. Soc. 2022, 39, 48–73. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/4860 (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Carrasco-Polaino, R.; Martín-Cárdaba, M.; Villar-Cirujano, E. Citizen participation in Twitter: Anti-vaccine controversies in times of COVID-19. [Participación ciudadana en Twitter: Polémicas anti-vacunas en tiempos de COVID-19]. Comunicar 2021, 69, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Curiel, C.; García-Gordillo, M. Indicadores de influencia de los políticos españoles en Twitter. Un análisis en el marco de las elecciones en Cataluña. Estud. Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico 2020, 26, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carral, U.; Tuñón, J. Estrategia de comunicación organizacional en redes sociales: Análisis electoral de la extrema derecha francesa en Twitter. El Prof. De La Inf. 2020, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, R. Twitter y Facebook en la Campaña Electoral del PP y del PSOE: Elecciones Autonómicas de Castilla y León 2015. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, C.A. El índice de engagement en redes sociales como predictor de los resultados en las elecciones generales de 2015 y 2016. IC-Rev. Científica De Inf. Y Comun. 2019, 16, 615–646. [Google Scholar]

- Papagianneas, S. Rebranding Europe. Fundamentals for Leadership Communication; ASP Editions: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- García, M.; Rivas de Roca, R. Estudio de la comunicación política en las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de 2019: La campaña ‘This time I’m voting’ y el sistema de ‘Spitzenkandidaten’ [Comunicación en congreso]. Comunicación y diversidad. In Proceedings of the Selección de comunicaciones del VII Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Española de Investigación de la Comunicación (AE-IC), Valencia, España, 27–30 June 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.; Castromil, A.R. Elecciones 2015 y 2016 en España: El debate de los temas a los “meta-temas” de agenda. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2020, 76, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugasti, R.; Sabés, F. Los issues de los candidatos en Twitter durante la campaña de las elecciones generales de 2011. ZER Rev. De Estud. De Comun. 2015, 20, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Comunicación y Poder; Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Caiani, M.; Guerra, S. Euroescepticism, Democracy and the Media: Communicating Europe, Contesting Europe; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fazekas, Z.; Adrian, S.; Schmitt, H.; Barberá, P.; Theocharis, Y. Elite-Public Interaction on Twitter: EU Issue Expansion in the Campaign. Eur. J. Political Res. 2022, 60, 376–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suau, G.; Pont, C. Microblogging electoral: Los usos de Twitter de Podemos y Ciudadanos y sus líderes Pablo iglesias y Albert Rivera en las elecciones generales españolas de 2016. Estud. Sobre El Mensaje Periodístico 2019, 25, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name/Institution | Account | Sector/Function | Country | Analysed Tweets |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steffen Seibert | @RegSprecher | Government Spokesperson | Germany | 67 |

| Jens Spahn | @jensspahn | Minister of Health | 41 | |

| BMG | @BMG_Bund | Ministry of Health | 247 | |

| Pedro Sánchez | @sanchezcastejon | Prime Minister | Spain | 125 |

| Salvador Illa | @salvadorilla | Minister of Health | 54 | |

| Carolina Darias | @CarolinaDarias | Minister of Health | 9 | |

| La Moncloa | @desdelamoncloa | Government | 514 | |

| Ministerio de Sanidad | @sanidadgob | Ministry of Health | 316 | |

| Emmanuel Macron | @EmmanuelMacron | Prime Minister | France | 110 |

| Olivier Véran | @olivierveran | Minister of Health | 86 | |

| Élysée | @Elysee | Government | 46 | |

| Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé | @Sante_Gouv | Ministry of Health | 140 | |

| Giuseppe Conte | @GiuseppeConteIT | Prime Minister | Italy | 34 |

| Roberto Speranza | @robersperanza | Minister of Health | 28 | |

| Palazzo Chigi | @Palazzo_Chigi | Government | 36 | |

| Ministero della Salute | @MinisteroSalute | Ministry of Health | 60 |

| Name/Institution | Tweets | Following | Followers | Followers/Following | Tweets/Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steffen Seibert | 13.800 | 154 | 1000 K | 6.493 | 1, 34 |

| Jens Spahn | 12.000 | 648 | 254, 5 K | 392 | 0, 82 |

| BMG | 11.000 | 995 | 276, 2 K | 277 | 4, 94 |

| Name/Institution | Tweets | Following | Followers | Followers/Following | Tweets/Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pedro Sánchez | 29.400 | 6.032 | 1.500 K | 248 | 2, 50 |

| Salvador Illa | 3.875 | 473 | 103,4 K | 218 | 1, 46 |

| Carolina Darias | 14.700 | 1.748 | 271 K | 15 | 0, 69 |

| La Moncloa | 46.300 | 199 | 756,8 K | 3.803 | 10, 28 |

| Ministerio de Sanidad | 18.800 | 691 | 651 K | 942 | 6, 32 |

| Name/Institution | Tweets | Following | Followers | Followers/Following | Tweets/Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emmanuel Macron | 10.200 | 722 | 7.000 K | 9.695 | 2, 20 |

| Olivier Véran | 8.740 | 463 | 329 K | 710 | 1, 72 |

| Élysée | 24.100 | 302 | 2.600 K | 8.609 | 0, 92 |

| Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé | 16.100 | 652 | 284, 2 K | 435 | 2, 80 |

| Name/Institution | Tweets | Following | Followers | Followers/Following | Tweets/Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giuseppe Conte | 1.460 | 135 | 1.000 K | 7.407 | 0, 68 |

| Roberto Speranza | 3.739 | 2.991 | 153, 4 K | 51 | 0, 56 |

| Palazzo Chigi | 7.012 | 1.814 | 804, 6 K | 443 | 0, 72 |

| Ministero della Salute | 4.536 | 225 | 259, 3 K | 1.152 | 1, 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tuñón Navarro, J.; Oporto Santofimia, E. EU Member States’ Institutional Twitter Campaigns on COVID-19 Vaccination: Analyses of Germany, Spain, France and Italy. Vaccines 2023, 11, 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030619

Tuñón Navarro J, Oporto Santofimia E. EU Member States’ Institutional Twitter Campaigns on COVID-19 Vaccination: Analyses of Germany, Spain, France and Italy. Vaccines. 2023; 11(3):619. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030619

Chicago/Turabian StyleTuñón Navarro, Jorge, and Emma Oporto Santofimia. 2023. "EU Member States’ Institutional Twitter Campaigns on COVID-19 Vaccination: Analyses of Germany, Spain, France and Italy" Vaccines 11, no. 3: 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030619

APA StyleTuñón Navarro, J., & Oporto Santofimia, E. (2023). EU Member States’ Institutional Twitter Campaigns on COVID-19 Vaccination: Analyses of Germany, Spain, France and Italy. Vaccines, 11(3), 619. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030619