What Motivates the Vaccination Rift Effect? Psycho-Linguistic Features of Responses to Calls to Get Vaccinated Differ by Source and Recipient Vaccination Status

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

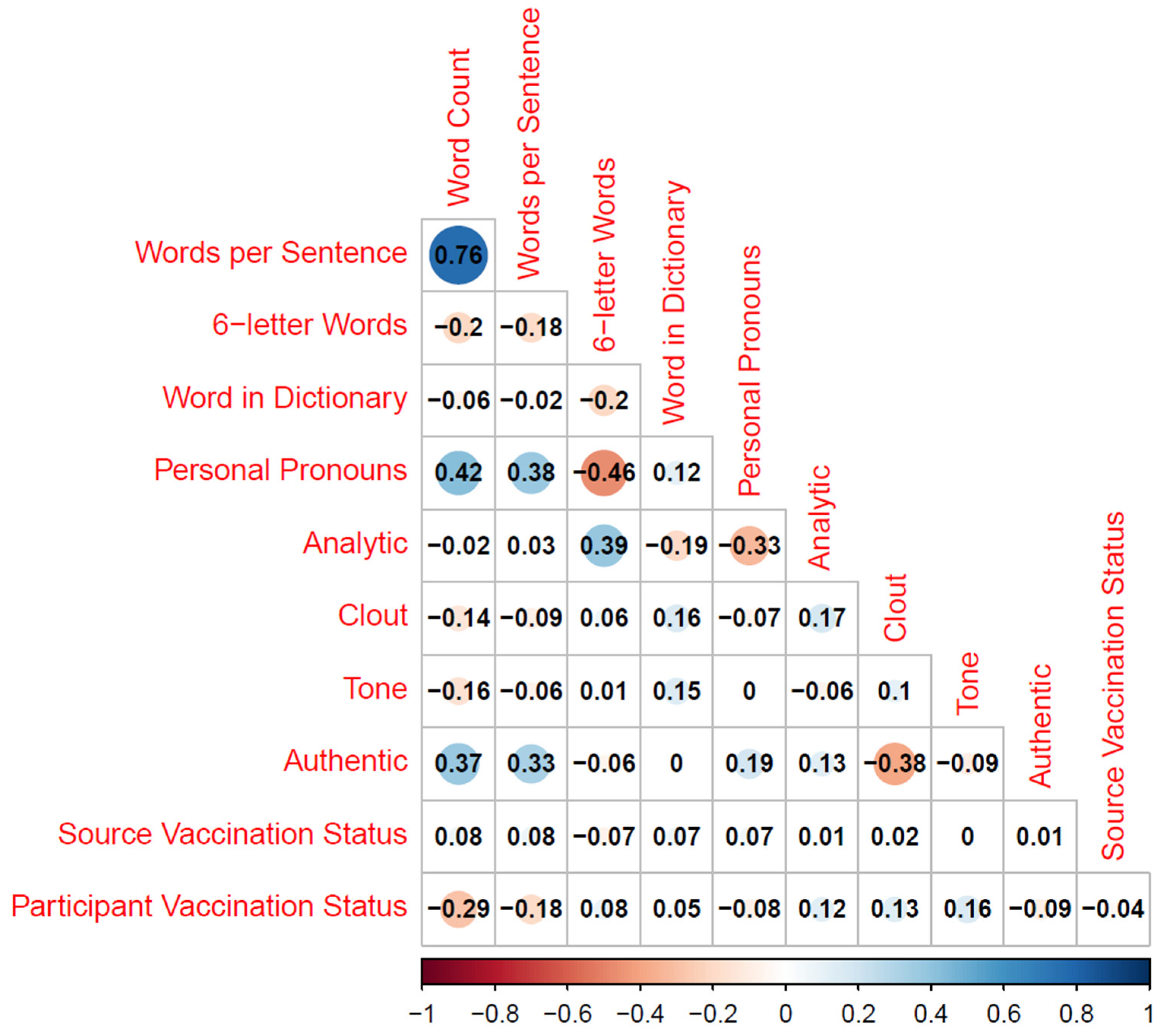

3. Results

3.1. Vaccination Rift

- Were more elaborate (longer and more words/sentence), but simpler (fewer words with six letters or more and more words in the dictionary)

- Addressed things more, but there was no indication for group processes

- Were not more emotional or less thought-through but included more drive-related words, especially those related to achievement, and more words related to general social processes.

3.2. Participant Vaccination Status

- Were more elaborate (longer and more words/sentence), but simpler (fewer words with six letters or more)

- Were less analytic, less confident, and less positive in tone, but more authentic

- Addressed things more, but showed no greater indicators of group processes

- Showed less positive and more negative emotions

- Referred more to spatial as well as social relations.

3.3. Matching of Participant and Source Vaccination Status

- The matching of source and participant vaccination status had no consistent effects on the observed psycho-linguistic processes.

- Apparently, the vaccination rift elicits psycho-linguistic processes that are independent of those elicited by recipients’ own vaccination status.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Critical Calls to Get Vaccinated

References

- World Health Organization. Report of the meeting of the WHO Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety (GACVS), 8–9 June 2021–July 2021. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2021, 96, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Rutten, L.J.F.; Zhu, X.; Leppin, A.L.; Ridgeway, J.L.; Swift, M.D.; Griffin, J.M.; St Sauver, J.L.; Virk, A.; Jacobson, R.M. Evidence-Based Strategies for Clinical Organizations to Address COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, H.; Attwell, K.; Danchin, M.; Marshall, H.; Corben, P.; Leask, J. Vaccine hesitancy, refusal and access barriers: The need for clarity in terminology. Vaccine 2018, 36, 6556–6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mohandes, A.; White, T.M.; Wyka, K.; Rauh, L.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.H.; Ratzan, S.C.; Lazarus, J.V. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among adults in four major US metropolitan areas and nationwide. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thürmer, J.L.; McCrea, S.M. The vaccination rift effect provides evidence that source vaccination status determines the rejection of calls to get vaccinated. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tu, P.; Beitsch, L.M. Confidence and Receptivity for COVID-19 Vaccines: A Rapid Systematic Review. Vaccines 2021, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Takahashi, M.; Luu, L.-A.N.; Borsfay, K.; Kovács, M.; Hou, W.K.; Hamama-Raz, Y.; Levin, Y. Psychological factors underpinning vaccine willingness in Israel, Japan and Hungary. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geipel, J.; Grant, L.H.; Keysar, B. Use of a language intervention to reduce vaccine hesitancy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsch, C.; Schmid, P.; Heinemeier, D.; Korn, L.; Holtmann, C.; Böhm, R. Beyond confidence: Development of a measure assessing the 5C psychological antecedents of vaccination. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggeri, K.; Većkalov, B.; Bojanić, L.; Andersen, T.L.; Ashcroft-Jones, S.; Ayacaxli, N.; Barea-Arroyo, P.; Berge, M.L.; Bjørndal, L.D.; Bursalıoğlu, A.; et al. The general fault in our fault lines. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 1369–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, J.N.; Klar, S.; Krupnikov, Y.; Levendusky, M.; Ryan, J.B. Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer, A.; Martel, C.; Brady, W.J.; Pärnamets, P.; Freedman, I.G.; Knowles, E.D.; Van Bavel, J.J. Partisan differences in physical distancing are linked to health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilewicz, M.; Soral, W. The politics of vaccine hesitancy: An ideological dual-process approach. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2021. online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrea, S.M.; Sherrin-Helm, M.; Thürmer, J.L.; Erion, C.J.G.; Krueger, K. Apologizing for intergroup criticism reduces rejection of government officials’ pro-vaccine messages. submitted.

- McCrea, S.M.; Thürmer, J.L.; Sherrin-Helm, M.; Erion, C.J.G.; Krueger, K. Ill-intended communication: Shared identity and conversational norm adherence reduce COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. submitted.

- Hornsey, M.J.; Esposo, S. Resistance to group criticism and recommendations for change: Lessons from the intergroup sensitivity effect. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2009, 3, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J.; Imani, A. Criticizing groups from the inside and the outside: An identity perspective on the intergroup sensitivity effect. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004, 30, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thürmer, J.L.; McCrea, S.M. Disentangling the Intergroup Sensitivity Effect: Defending the ingroup or enforcing general norms? Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 51, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrea, S.M.; Erion, C.J.G.; Thürmer, J.L. Why punish critical outgroup commenters? Social identity, general norms, and retribution. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2022, 61, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, L.; Verkuyten, M. Rules of engagement: Reactions to internal and external criticism in public debate. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 59, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallis, M.; Bacon, S.; Corace, K.; Joyal-Desmarais, K.; Sheinfeld Gorin, S.; Paduano, S.; Presseau, J.; Rash, J.; Mengistu Yohannes, A.; Lavoie, K. Ending the pandemic: How behavioural science can help optimize global COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Vaccines 2022, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamm, T.A.; Partheymüller, J.; Mosor, E.; Ritschl, V.; Kritzinger, S.; Eberl, J.-M. Coronavirus vaccine hesitancy among unvaccinated Austrians: Assessing underlying motivations and the effectiveness of interventions based on a cross-sectional survey with two embedded conjoint experiments. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2022, 17, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Mehl, M.R.; Niederhoffer, K.G. Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanning, K.; Pauletti, R.E.; King, L.A.; McAdams, D.P. Personality development through natural language. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keblusek, L.; Giles, H.; Maass, A. Communication and group life: How language and symbols shape intergroup relations. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2017, 20, 632–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Swol, L.M.; Kane, A.A. Language and group processes: An integrative, interdisciplinary review. Small Group Res. 2019, 50, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.A.; van Swol, L.M. Using linguistic inquiry and word count software to analyze group interaction language data. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2022. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.L.; Blackburn, K.G.; Pennebaker, J.W. The narrative arc: Revealing core narrative structures through text analysis. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanning, K.; Wetherell, G.; Warfel, E.A.; Boyd, R.L. Changing channels? A comparison of Fox and MSNBC in 2012, 2016, and 2020. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2021, 21, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thürmer, J.L.; McCrea, S.M.; McIntyre, B.M. Motivated collective defensiveness: Group members prioritize counterarguing out-group criticism over getting their work done. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2019, 10, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thürmer, J.L.; McCrea, S.M. Beyond motivated reasoning: Hostile reactions to critical comments from the outgroup. Motiv. Sci. 2018, 4, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Swol, L.M.; Carlson, C.L. Language use and influence among minority, majority, and homogeneous group members. Commun. Res. 2017, 44, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Swol, L.M.; Ahn, P.H.; Prahl, A.; Gong, Z. Language use in group discourse and its relationship to group processes. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211001852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdue, C.W.; Dovidio, J.F.; Gurtman, M.B.; Tyler, R.B. Us and them: Social categorization and the process of intergroup bias. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thürmer, J.L.; McCrea, S.M. Intergroup sensitivity in a divided society: Calls for unity and reconciliatory behavior during the 2020 US presidential election. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2022. Manuscript accepted for publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W.; Nijstad, B.A. Mental set and creative thought in social conflict: Threat rigidity versus motivated focus. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, A.; Jørgensen, F.; Petersen, M.B. Discriminatory attitudes against unvaccinated people during the pandemic. Nature 2023, 613, 704–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, R.C.; Walther, M.P.; Tata, C.S. formr: A study framework allowing for automated feedback generation and complex longitudinal experience-sampling studies using R. Behav. Res. Methods 2020, 52, 376–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Booth, R.J.; Francis, M.E. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC, 2015; Pennebaker Conglomerates, Inc.: Austin, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M.; Horn, A.B.; Mehl, M.R.; Haug, S.; Pennebaker, J.W.; Kordy, H. Computergestützte quantitative Textanalyse. Diagnostica 2008, 54, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, T.; Boyd, R.L.; Pennebaker, J.W.; Mehl, M.R.; Martin, M.; Wolf, M.; Horn, A.B. “LIWC auf Deutsch”: The Development, Psychometrics, and Introduction of DE-LIWC2015. PsyArXiv 2018. preprint. [Google Scholar]

- R-Core-Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; RStudio, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Revelle, W.R. Psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research, R package version 1.0.8; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2020.

- Sutton, R.M.; Elder, T.J.; Douglas, K.M. Reactions to internal and external criticism of outgroups: Social convention in the intergroup sensitivity effect. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 32, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thürmer, J.L.; McCrea, S.M. Behavioral consequences of intergroup sensitivity. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2023, 17, e12716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thürmer, J.L.; Stadler, J.; McCrea, S.M. Intergroup sensitivity and promoting sustainable consumption: Meat eaters reject vegans’ call for a plant-based diet. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thürmer, J.L. Catholic Christians reject Protestants’ criticism and retaliate in their prayers. submitted.

- Holtzman, N.S.; Tackman, A.M.; Carey, A.L.; Brucks, M.S.; Küfner, A.C.P.; Deters, F.G.; Back, M.D.; Donnellan, M.B.; Pennebaker, J.W.; Sherman, R.A.; et al. Linguistic Markers of Grandiose Narcissism: A LIWC Analysis of 15 Samples. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 38, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, C.S.; Mujeeb, A.A.; Mirza, M.S.; Chaudhry, B.; Khan, S.J. Global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: A systematic review of associated social and behavioral factors. Vaccines 2022, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, G.; Balgobin, K.; Michel, A.; Limaye, R.J. Vaccine communication: Appeals and messengers most effective for COVID-19 vaccine uptake in Ukraine. Vaccines 2023, 11, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, D.; Ilie, D.-G.; Constantinescu, C.; Fîrțală, V. Vaccinating against COVID-19: The correlation between pro-vaccination attitudes and the belief that our peers want to get vaccinated. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro-Ascuy, D.; Cifuentes-Muñoz, N.; Avaria, A.; Pereira-Montecinos, C.; Cruzat, G.; Peralta-Arancibia, K.; Zorondo-Rodríguez, F.; Fuenzalida, L.F. Factors influencing the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines in a country with a high vaccination rate. Vaccines 2022, 10, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N.; Costa, D.; Costa, D.; Keating, J.; Arantes, J. Predicting COVID-19 vaccination intention: The determinants of vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Zain, A.; Chen, Y.; Kim, S.-H. Adverse mentions, negative sentiment, and emotions in COVID-19 vaccine tweets and their association with vaccination uptake: Global comparison of 192 countries. Vaccines 2022, 10, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unvaccinated/Recovered Participants | Vaccinated Participants | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Source | |||||||

| Unvaccinated | Vaccinated | Unvaccinated | Vaccinated | |||||

| M (SD) | Mdn [Range] | M (SD) | Mdn [Range] | M (SD) | Mdn [Range] | M (SD) | Mdn [Range] | |

| Summary Scores and Grammar | ||||||||

| Word count | 54.28 (69.60) | 30 [0; 516] | 53.61 (81.75) | 33 [0; 1101] | 24.14 (34.65) | 14 [0; 294] | 32.03 (64.60) | 17 [0; 786] |

| Words per sentence | 12.53 (6.88) | 12.39 [0; 29] | 13.08 (7.12) | 12.43 [0; 52] | 9.95 (7.50) | 9 [0; 54] | 11.39 (7.56) | 10.94 [0; 43] |

| 6-letter words | 34.93 (19.69) | 31.77 [0; 100] | 30.72 (14.09) | 30.35 [0; 100] | 38.17 (21.93) | 33.33 [0; 100] | 34.81 (20.23) | 32.84 [0; 100] |

| Words in dictionary | 80.98 (18.58) | 84.62 [0; 100] | 83.33 (12.20) | 84.34 [0; 100] | 80.92 (18.07) | 83.59 [0; 100] | 85.07 (13.39) | 86.67 [0; 100] |

| Analytic | 46.47 (39.83) | 41.25 [0; 99] | 43.93 (39.43) | 34.88 [0; 99] | 52.23 (42.07) | 57.23 [0; 99] | 57.31 (41.22) | 75.12 [0; 99] |

| Clout | 42.89 (27.13) | 42.96 [0; 99] | 46.14 (28.90) | 46.52 [0; 99] | 51.49 (27.67) | 61.81 [0; 99] | 51.53 (28.92) | 57.43 [0; 99] |

| Authentic | 46.96 (40.14) | 44.95 [0; 99] | 43.84 (38.32) | 39.33 [0; 99] | 37.48 (41.02) | 16.77 [0; 99] | 38.67 (40.57) | 16.23 [0; 99] |

| Tone | 35.18 (36.90) | 17.39 [0; 99] | 34.48 (37.67) | 17.39 [0; 99] | 43.89 (40.76) | 17.39 [0; 99] | 47.18 (41.92) | 17.39 [0; 99] |

| Personal pronouns | 5.46 (5.82) | 4.55 [0; 33.33] | 6.30 (5.98) | 5.12 [0; 33.33] | 5.23 (6.89) | 2.95 [0; 50] | 5.75 (6.52) | 4.65 [0; 36.36] |

| Impersonal pronouns | 6.65 (6.84) | 5.58 [0; 50] | 8.15 (7.89) | 6.85 [0; 50] | 4.24 (8.33) | 0.00 [0; 100] | 5.13 (6.96) | 2.82 [0; 50] |

| Emotion and Cognition | ||||||||

| Positive emotion | 3.21 (5.64) | 2.06 [0; 50] | 3.11 (5.00) | 1.89 [0; 50] | 7.67 (16.97) | 0.79 [0; 100] | 8.80 (18.79) | 2.76 [0; 100] |

| Negative emotion | 3.06 (7.60) | 1.87 [0; 100] | 3.11 (7.19) | 1.44 [0; 100] | 1.55 (3.11) | 0.00 [0; 20] | 1.76 (3.18) | 0.00 [0; 25] |

| Cognitive processes | 27.03 (16.09) | 25.00 [0; 100] | 25.48 (14.40) | 23.17 [0; 100] | 29.40 (23.11) | 25.00 [0; 100] | 28.62 (21.61) | 24.07 [0; 100] |

| General Processes | ||||||||

| Social | 10.56 (8.94) | 10.00 [0; 50] | 12.31 (8.90) | 11.11 [0; 50] | 9.12 (9.70) | 9.00 [0; 50] | 10.74 (11.03) | 9.58 [0; 60] |

| Perception | 0.98 (1.89) | 0 [0; 14.29] | 0.87 (1.58) | 0 [0; 12.50] | 1.18 (6.12) | 0 [0; 100] | 2.03 (10.00) | 0 [0; 100] |

| Biological | 3.96 (5.35) | 2.88 [0; 50] | 4.09 (4.49) | 3.45 [0; 33.33] | 3.62 (6.20) | 0 [0; 50] | 4.13 (6.75) | 1.94 [0; 50] |

| Relative | 11.98 (10.73) | 11.90 [0; 75] | 11.89 (8.40) | 12.04 [0; 66.67] | 10.43 (10.63) | 10.00 [0; 50] | 11.23 (10.13) | 10.35 [0; 50] |

| Informal | 1.55 (8.87) | 0 [0; 100] | 1.62 (7.37) | 0 [0; 100] | 1.71 (8.27) | 0 [0; 100] | 2.82 (12.76) | 0 [0; 100] |

| Drives/Motives | 8.85 (8.77) | 7.84 [0; 100] | 9.23 (8.58) | 8.33 [0; 100] | 11.66 (16.72) | 7.24 [0; 100] | 11.85 (14.28) | 9.09 [0; 100] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thürmer, J.L.; McCrea, S.M. What Motivates the Vaccination Rift Effect? Psycho-Linguistic Features of Responses to Calls to Get Vaccinated Differ by Source and Recipient Vaccination Status. Vaccines 2023, 11, 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030503

Thürmer JL, McCrea SM. What Motivates the Vaccination Rift Effect? Psycho-Linguistic Features of Responses to Calls to Get Vaccinated Differ by Source and Recipient Vaccination Status. Vaccines. 2023; 11(3):503. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030503

Chicago/Turabian StyleThürmer, J. Lukas, and Sean M. McCrea. 2023. "What Motivates the Vaccination Rift Effect? Psycho-Linguistic Features of Responses to Calls to Get Vaccinated Differ by Source and Recipient Vaccination Status" Vaccines 11, no. 3: 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030503

APA StyleThürmer, J. L., & McCrea, S. M. (2023). What Motivates the Vaccination Rift Effect? Psycho-Linguistic Features of Responses to Calls to Get Vaccinated Differ by Source and Recipient Vaccination Status. Vaccines, 11(3), 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11030503