Investigating Attitudes, Motivations and Key Influencers for COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake among Late Adopters in Urban Zimbabwe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Sites and Sampling

2.3. Study Procedures

2.4. Study Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethics Approvals

3. Results

3.1. Vaccine Convenience

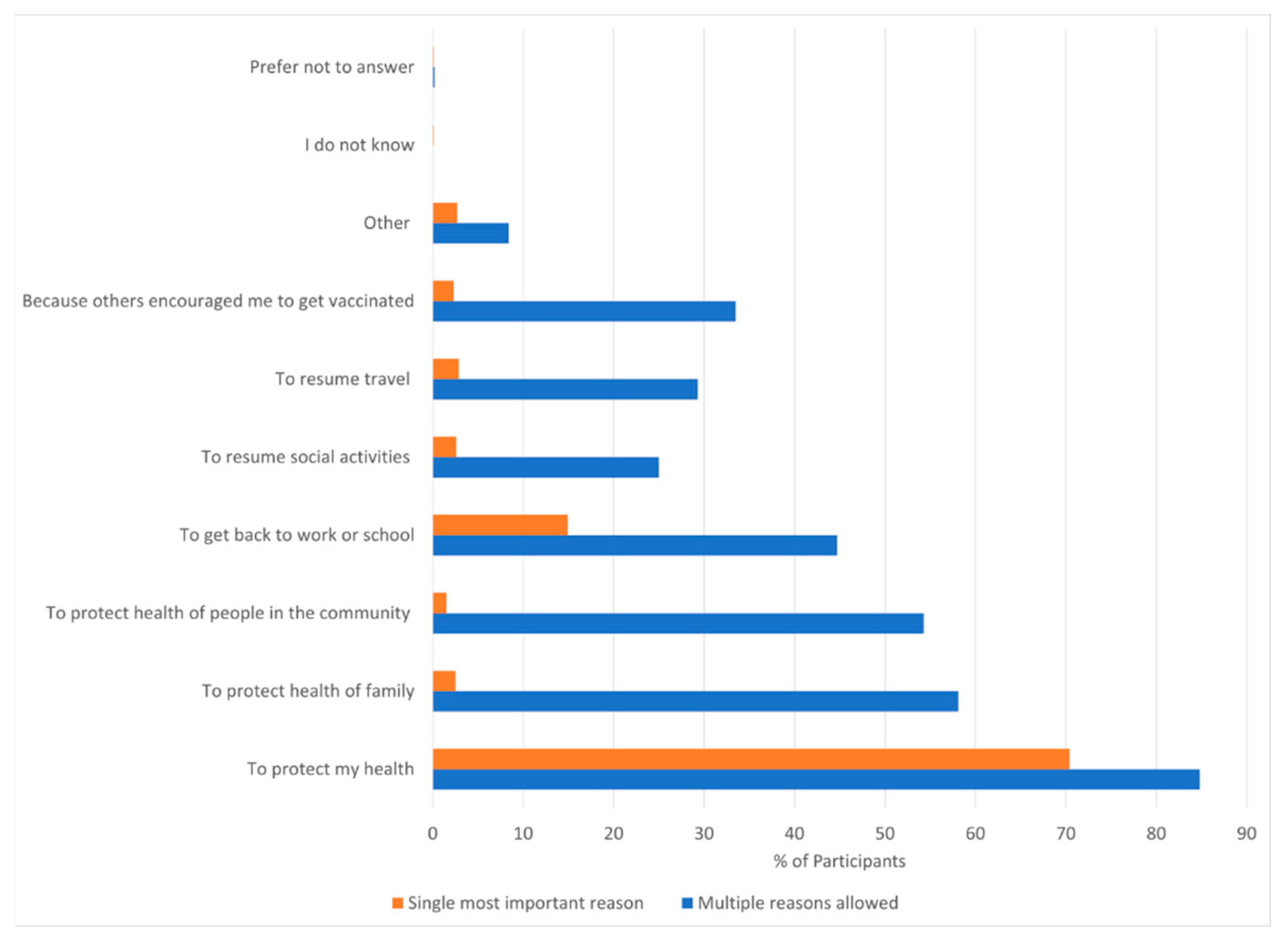

3.2. Vaccine Confidence

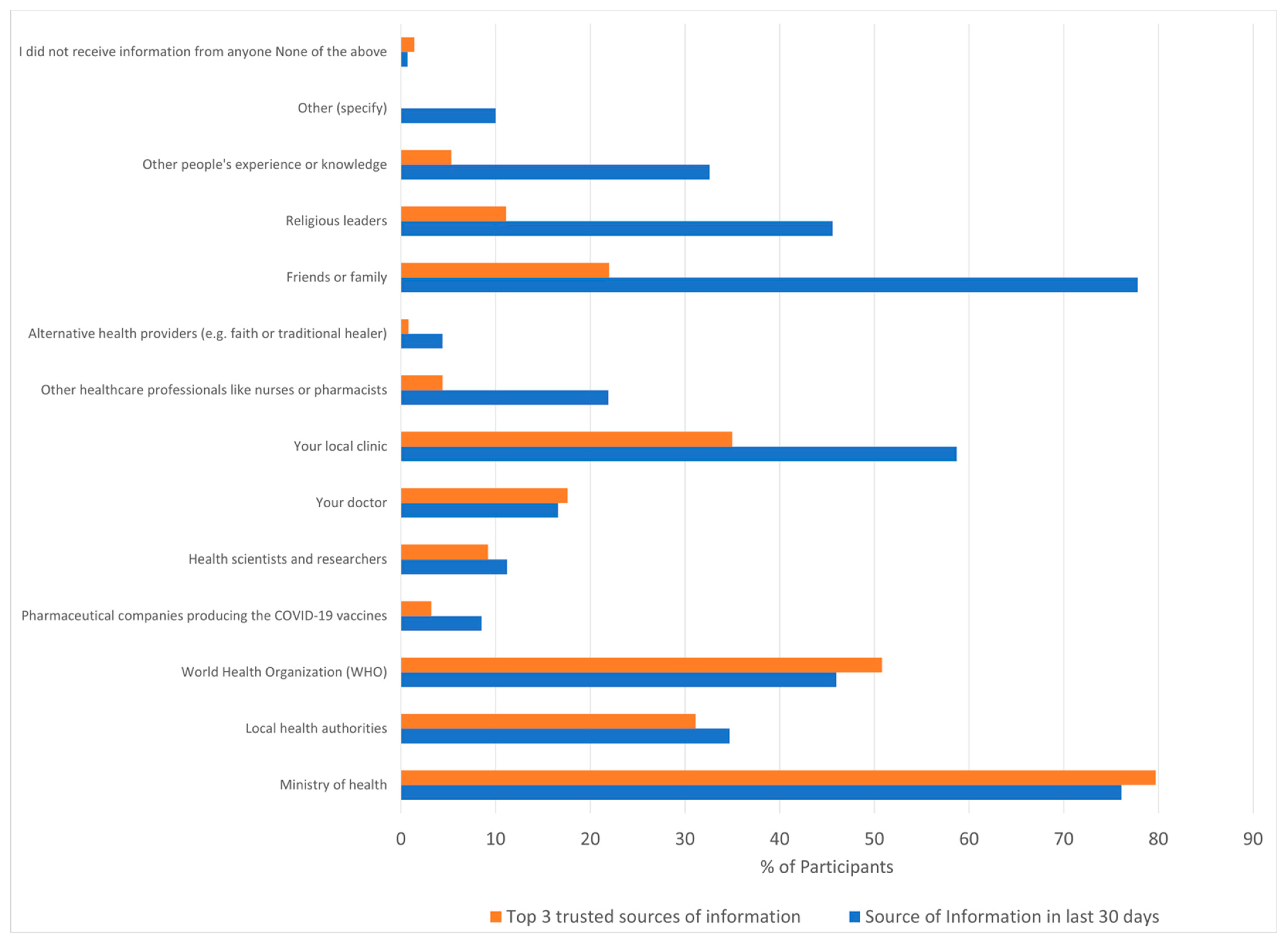

3.3. Key Influencers

3.4. Sources of Information

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2022. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- WHO. COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker and Landscape. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- WHO. COVID-19 Vaccines. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/covid-19-vaccines (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Wouters, O.J.; Shadlen, K.C.; Salcher-Konrad, M.; Pollard, A.J.; Larson, H.J.; Teerawattananon, Y.; Jit, M. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: Production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet 2021, 397, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Ten Threats to Global Health in 2019. Available online: ttps://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- WHO. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Dubé, E.; Gagnon, D.; MacDonald, N.; Bocquier, A.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Verger, P. Underlying factors impacting vaccine hesitancy in high income countries: A review of qualitative studies. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2018, 17, 989–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danis, K.; Georgakopoulou, T.; Stavrou, T.; Laggas, D.; Panagiotopoulos, T. Socioeconomic factors play a more important role in childhood vaccination coverage than parental perceptions: A cross-sectional study in Greece. Vaccine 2010, 28, 1861–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, S.; Lawan, U. Factors predicting BCG immunization status in northern Nigeria: A behavioral-ecological perspective. J. Child Health Care 2009, 13, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otieno, N.A.; Nyawanda, B.O.; Audi, A.; Emukule, G.; Lebo, E.; Bigogo, G.; Ochola, R.; Muthoka, P.; Widdowson, M.-A.; Shay, D.K.; et al. Demographic, socio-economic and geographic determinants of seasonal influenza vaccine uptake in rural western Kenya, 2011. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6699–6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- de Figueiredo, A.; Simas, C.; Karafillakis, E.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Mapping global trends in vaccine confidence and investigating barriers to vaccine uptake: A large-scale retrospective temporal modelling study. Lancet 2020, 396, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solis Arce, J.S.; Warren, S.S.; Meriggi, N.F.; Scacco, A.; McMurry, N.; Voors, M.; Syunyaev, G.; Malik, A.A.; Aboutajdine, S.; Adeojo, O.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. COVID-19 Vaccination Bulletin. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus-covid-19/vaccines/monthly-bulletin (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- WHO. Achieving 70% COVID-19 Immunization Coverage by Mid-2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-12-2021-achieving-70-covid-19-immunization-coverage-by-mid-2022#:~:text=%5B4%5D%20These%20targets%20were%20then,population%20coverage%20by%20mid%2D2022.2021 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Anjorin, A.A.; Odetokun, I.A.; Abioye, A.I.; Elnadi, H.; Umoren, M.V.; Damaris, B.F.; Eyedo, J.; Umar, H.I.; Nyandwi, J.B.; Abdalla, M.M.; et al. Will Africans take COVID-19 vaccination? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D.E.; Kasprzyk, D. Theory of Reasoned Action, Theory of Planned Behavior, and the Integrated Behavioral Model. In Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th ed.; Glanz, K., Rimer, K.B., Viswanath, K.V., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, I.M.; Strecher, V.J.; Becker, M.H. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, H.J.; de Figueiredo, A.; Xiahong, Z.; Schulz, W.S.; Verger, P.; Johnston, I.G.; Cook, A.R.; Jones, N.S. The State of Vaccine Confidence 2016: Global Insights Through a 67-Country Survey. EBioMedicine 2016, 12, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briss, P.A.; Rodewald, L.E.; Hinman, A.R.; Shefer, A.M.; Strikas, R.A.; Bernier, R.R.; Carande-Kulis, V.G.; Yusuf, H.R.; Ndiaye, S.M.; Williams, S.M. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to improve vaccination coverage in children, adolescents, and adults. The Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000, 18, 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkdale, C.L.; Nebout, G.; Megerlin, F.; Thornley, T. Benefits of pharmacist-led flu vaccination services in community pharmacy. Ann. Pharm. Fr. 2017, 75, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, S.B.; Benjamin, R.M.; Brewer, N.T.; Buttenheim, A.M.; Callaghan, T.; Caplan, A.; Carpiano, R.M.; Clinton, C.; DiResta, R.; Elharake, J.A.; et al. Promoting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: Recommendations from the Lancet Commission on Vaccine Refusal, Acceptance, and Demand in the USA. Lancet 2021, 398, 2186–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.S.; Mohareb, A.M.; Valdes, C.; Price, C.; Jollife, M.; Regis, C.; Munshi, N.; Taborda, E.; Lautenschlager, M.; Fox, A.; et al. Expanding COVID-19 vaccine access to underserved populations through implementation of mobile vaccination units. Prev. Med. 2022, 163, 107226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economist. Informal Employment Dominates: Economist Intelligence Unit. 2015. Available online: http://country.eiu.com/article.aspx?articleid=453276029&Country=Zimbabwe&topic=Economy (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Tlale, L.B.; Gabaitiri, L.; Totolo, L.K.; Smith, G.; Puswane-Katse, O.; Ramonna, E.; Mothowaeng, B.; Tlhakanelo, J.; Masupe, T.; Rankgoane-Pono, G.; et al. Acceptance rate and risk perception towards the COVID-19 vaccine in Botswana. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, B.; Biddle, N.; Gray, M.; Sollis, K. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance: Correlates in a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the Australian population. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, E.; Reeve, K.S.; Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Moore, J.; Blake, M.; Green, M.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Benzeval, M.J. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 94, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detoc, M.; Bruel, S.; Frappe, P.; Tardy, B.; Botelho-Nevers, E.; Gagneux-Brunon, A. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7002–7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypsa, V.; Roussos, S.; Engeli, V.; Paraskevis, D.; Tsiodras, S.; Hatzakis, A. Trends in COVID-19 Vaccination Intent, Determinants and Reasons for Vaccine Hesitancy: Results from Repeated Cross-Sectional Surveys in the Adult General Population of Greece during November 2020-June 2021. Vaccines 2022, 10, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murewanhema, G.; Dzinamarira, T.; Herrera, H.; Musuka, G. COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant women in Zimbabwe: A public health challenge that needs an urgent discourse. Public Health Pr. 2021, 2, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germani, F.; Biller-Andorno, N. The anti-vaccination infodemic on social media: A behavioral analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZIMPHIA. Zimbabwe Population Based HIV Impact Assessment. 2020. Available online: https://phia.icap.columbia.edu (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Yang, X.; Sun, J.; Patel, R.C.; Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Zheng, Q.; Olex, A.L.; Olatosi, B.; Weissman, S.B.; Islam, J.Y.; et al. Associations between HIV infection and clinical spectrum of COVID-19: A population level analysis based on US National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C) data. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e690–e700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomah, D.K.; Reyes-Uruena, J.; Diaz, Y.; Moreno, S.; Aceiton, J.; Bruguera, A.; Vivanco-Hidalgo, R.M.; Llibre, J.M.; Domingo, P.; Falco, V.; et al. Sociodemographic, clinical, and immunological factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and severe COVID-19 outcomes in people living with HIV: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e701–e710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corey, L.; Beyrer, C.; Cohen, M.S.; Michael, N.L.; Bedford, T.; Rolland, M. SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Patients with Immunosuppression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 562–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulda, E.S.; Fitch, K.V.; Overton, E.T.; Zanni, M.V.; Aberg, J.A.; Currier, J.S.; Lu, M.T.; Malvestutto, C.; Fichtenbaum, C.J.; Martinez, E.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Rates in a Global HIV Cohort. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 225, 603–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, L.M.; Ojikutu, B.O.; Tyagi, K.; Klein, D.J.; Mutchler, M.G.; Dong, L.; Lawrence, S.J.; Thomas, D.R.; Kellman, S. COVID-19 Related Medical Mistrust, Health Impacts, and Potential Vaccine Hesitancy Among Black Americans Living with HIV. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2021, 86, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Guidelines for Managing Advanced HIV Disease and Rapid Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550062 (accessed on 26 June 2022).

- Muhindo, R.; Okoboi, S.; Kiragga, A.; King, R.; Arinaitwe, W.J.; Castelnuovo, B. COVID-19 vaccine acceptability, and uptake among people living with HIV in Uganda. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0278692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, B.; Sayılır, M.Ü.; Zengin, N.Y.; Küçük, Ö.N.; Soylu, A.R. Does the COVID-19 Vaccination Rate Change According to the Education and Income: A Study on Vaccination Rates in Cities of Turkey between 2021-September and 2022-February. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownstein, N.C.; Reddy, H.; Whiting, J.; Kasting, M.L.; Head, K.J.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Giuliano, A.R.; Gwede, C.K.; Meade, C.D.; Christy, S.M. COVID-19 vaccine behaviors and intentions among a national sample of United States adults ages 18-45. Prev. Med. 2022, 160, 107038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairat, S.; Zou, B.; Adler-Milstein, J. Factors and reasons associated with low COVID-19 vaccine uptake among highly hesitant communities in the US. Am. J. Infect. Control 2022, 50, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, M.E.; Christy, S.M.; Winger, J.G.; Vadaparampil, S.T.; Mosher, C.E. Self-efficacy and HPV Vaccine Attitudes Mediate the Relationship Between Social Norms and Intentions to Receive the HPV Vaccine Among College Students. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, S.C.; Hilyard, K.M.; Jamison, A.M.; An, J.; Hancock, G.R.; Musa, D.; Freimuth, V.S. The influence of social norms on flu vaccination among African American and White adults. Health Educ. Res. 2017, 32, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.A.; Cook, R.E.; Button, J.A. Parent and Peer Norms are Unique Correlates of COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions in a Diverse Sample of U.S. Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agranov, M.; Elliott, M.; Ortoleva, P. The importance of Social Norms against Strategic Effects: The case of Covid-19 vaccine uptake. Econ. Lett. 2021, 206, 109979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunçgenç, B.; El Zein, M.; Sulik, J.; Newson, M.; Zhao, Y.; Dezecache, G.; Deroy, O. Social influence matters: We follow pandemic guidelines most when our close circle does. Br. J. Psychol. 2021, 112, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Parker, T.; Pejavara, K.; Smith, D.; Tu, R.; Tu, P. “I Would Never Push a Vaccine on You”: A Qualitative Study of Social Norms and Pressure in Vaccine Behavior in the U.S. Vaccines 2022, 10, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, P.A.; Logie, C.H.; Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Baiden, P.; Tepjan, S.; Rubincam, C.; Doukas, N.; Asey, F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.L.; Wiysonge, C. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 National Preparedness Collaborators. Pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: An exploratory analysis of infection and fatality rates, and contextual factors associated with preparedness in 177 countries, from Jan 1, 2020, to Sept 30, 2021. Lancet 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lamot, M.; Kerman, K.; Kirbiš, A. Distrustful, Dissatisfied, and Conspiratorial: A Latent Profile Analysis of COVID-19 Vaccination Rejection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, M.; Seale, H.; Chughtai, A.A.; Salmon, D.; MacIntyre, C.R. Trust in government, intention to vaccinate and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A comparative survey of five large cities in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2498–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu, E.K.; Oloruntoba, R.; Osuagwu, U.L.; Bhattarai, D.; Miner, C.A.; Goson, P.C.; Langsi, R.; Nwaeze, O.; Chikasirimobi, T.G.; Ovenseri-Ogbomo, G.O.; et al. Risk perception of COVID-19 among sub-Sahara Africans: A web-based comparative survey of local and diaspora residents. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, R.; Nguse, T.M.; Habte, B.M.; Fentie, A.M.; Gebretekle, G.B. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Ethiopian healthcare workers. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiysonge, C.S.; Alobwede, S.M.; de Marie, C.K.P.; Kidzeru, E.B.; Lumngwena, E.N.; Cooper, S.; Goliath, R.; Jackson, A.; Shey, M.S. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy among healthcare workers in South Africa. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2022, 21, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (Female) | 508 (50%) |

| Median age (IQR) | 30 (22–39) |

| Age groups | |

| 18–25 (Youth) | 368 (36.2%) |

| 26–39 (Young adults) | 409 (40.3%) |

| ≥40 (Older adults) | 239 (23.5%) |

| Ethnicity (Black African) | 1016 (100%) |

| Highest Level of Education | |

| No formal schooling | 5 (0.5%) |

| Primary school 1 | 84 (8.3%) |

| Lower Secondary school 2 | 735 (72.4%) |

| Higher Secondary 3 | 117 (11.5%) |

| Tertiary Education | 74 (7.3%) |

| Co-morbid conditions | |

| Diabetes | 15 (1.5%) |

| Cardiac Disease | 4 (0.4%) |

| Respiratory Illness | 23 (2.3%) |

| Hypertension | 67 (6.6%) |

| HIV | 126 (12.4%) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| High 4 | 172 (16.9%) |

| Middle 5 | 598 (58.9%) |

| Low 6 | 246 (24.2%) |

| Internet use | |

| In the past 30 days have you used the Internet? | 420 (41.4%) |

| Personal COVID experience | |

| Know someone who became seriously ill or died as a result of COVID | 428 (42.1%) |

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Frequency (N, %) | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| Gender | Male | 508 (50.0%) | 1 | |||

| Female | 508 (50.0%) | 1.573 (1.209, 2.045) | 0.001 | 1.508 (1.156,1.967) | 0.002 | |

| Age (y) | 18–25 | 368 (36.2%) | 1 | |||

| 26–39 | 409 (40.3%) | 1.446 (1.069, 1.957) | 0.017 | 1.371 (1.01, 1.862) | 0.043 | |

| ≥40 | 239 (23.5%) | 0.931 (0.665, 1.304) | 0.679 | 0.869 (0.617, 1.223) | 0.42 | |

| Education | Primary * | 89 (8.8%) | 1 | |||

| Lower secondary | 735 (72.4%) | 1.179 (0.747, 1.861) | 0.481 | |||

| Higher Secondary | 117 (11.5%) | 1.326 (0.741, 2.374) | 0.342 | |||

| Tertiary | 74 (7.3%) | 1.026 (0.541, 1.945) | 0.938 | |||

| Economic status | High | 172 (16.9%) | 1 | |||

| Middle | 598 (58.9%) | 0.885 (0.618, 1.270) | 0.508 | |||

| Low | 246 (24.2%) | 1.122 (0.738, 1.707) | 0.590 | |||

| Personal COVID Experience | No | 428 (42.1%) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 588 (57.9%) | 0.669 (0.514, 0.870) | 0.003 | 0.693 (0.53, 0.905) | 0.007 | |

| HIV status | Negative | 126 (12.4%) | 1 | |||

| Positive | 890 (87.6%) | 1.054 (0.708, 1.569) | 0.795 | |||

| Internet use in last 30 days | No | 420 (41.4%) | 1 | |||

| Yes | 594 (58.6%) | 0.773 (0.594, 1.006) | 0.056 | |||

| Major Concerns | Immediate Side Effects | Long-Term Health Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| Gender | Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Female | 1.454 (1.098, 1.923) | 0.009 * | 1.342 (1.044, 1.725) | 0.022 * | 1.416 (1.106, 1.812) | 0.006 * | |

| Age (years) | 18–25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 26–39 | 1.439 (1.036, 1.998) | 0.030 * | 1.48 (1.109, 1.975) | 0.008 * | 1.608 (1.211, 2.135) | 0.001 * | |

| ≥40 | 2.329 (1. 585, 3.422) | <0.001 * | 1.055 (0.76, 1.465) | 0.749 | 1.142 (0.824, 1.582) | 0.426 | |

| Education | Primary | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Lower secondary | 0.938 (0.576, 1.526) | 0.796 | 0.949 (0.603, 1.491) | 0.819 | 1.172 (0.754, 1.821) | 0.48 | |

| Higher Secondary | 1.162 (0.614, 2.199) | 0.645 | 0.773 (0.441, 1.355) | 0.369 | 1.219 (0.702, 2.117) | 0.482 | |

| Tertiary | 1.338 (0.665, 2.688) | 0.414 | 0.586 (0.313, 1.094) | 0.093 | 1.317(0.709, 2.443) | 0.383 | |

| Economic status | High | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Middle | 0.842 (0.577, 1.228) | 0.371 | 1.075 (0.709, 1.560) | 0.803 | 1.28 (0.866, 1.891) | 0.215 | |

| Low | 1.142 (0.733, 1.779) | 0.558 | 0.905 (0.642, 1.278) | 0.572 | 1.016 (0.723, 1.427) | 0.926 | |

| Personal Covid Experience | No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.710 (0.536, 0.940) | 0.017 * | 0.852 (0.661, 1.097) | 0.215 | 0.688 (0.536, 0.884) | 0.003 * | |

| HIV status | Negative | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Positive | 1. 250 (0.83, 1.884) | 0.285 | 1.558 (1.047, 2.23) | 0.029 * | 1.527 (1.044, 2.233) | 0.029 * | |

| Internet use in last 30 days | No | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.210 (0.896, 1.635) | 0.214 | 0.778 (0.604, 1.003) | 0.053 | 1.158 (0.902, 1.488) | 0.25 | |

| Concern | Frequency (N = 293) | Example Statements and Thematic Areas Regarding “Other Concerns” |

|---|---|---|

| Death | 75 (25.6%) | Feared from hearsay that vaccines would kill after a certain time Feared death and becoming a “Zombie” after vaccination Feared dying soon after vaccination I am afraid that I will not survive for 2 years after receiving the vaccine |

| Health Effect of vaccination | 43 (14.68%) | “Someone in Bulawayo got vaccinated and experienced necrosis” Feared fainting or stroke due to vaccination, too many people at site Husband was saying no-one in his house gets vaccinated because he has family members who “got sick” after vaccination Feared that vaccine would distort body parts Blindness Blood clotting |

| Prevailing conspiracy theories | 27 (9.22%) | Feared vaccine was to depopulate Some doctors from affected countries spoke negatively about vaccines. It is a created disease to wipe out people, dosage for Africans may be deadly Feared some foreign agent instead of the vaccine being injected into him “I think the whites want to depopulate Africans” |

| Pregnant or Breastfeeding concerns/interactions | 27 (9.22%) | Was pregnant so feared for baby I was pregnant when it started so was afraid to affect baby Effects of vaccine on pregnant wife Breast milk may dry off I was pregnant so was told l can’t |

| Lack of trust or understanding of vaccine/manufacturer | 26 (8.87%) | Was not trusting the vaccine Feared the coronavirus being injected into him instead of actual vaccine Concerned about manufacturers of the vaccine, that it came from China Feared that the vaccine was fake |

| Effect on Fertility | 21 (7.17%) | The vaccine causes infertility |

| Drug-Drug interactions and/or comorbid conditions | 21 (7.17%) | Feared negative interactions between vaccine and underlying diabetes issue Won’t it affect my BP? Feared contraindications between TB medication he was taking and vaccine |

| Injection site pain/swelling, fear of needles | 16 (5.46%) | Fear of needles |

| Convenience of vaccination | 11 (3.75%) | “Social media was saying bad things so we were afraid to come, it’s also taking too long in the queue, 1 nurse dealing with too many people” The vaccine site a bit far from home Identification documents were not close to him, so he couldn’t get vaccinated |

| HIV infection and/or co-interaction with ART | 10 (3.41%) | Fear since I am HIV positive Did not understand the whole vaccination issue, was afraid of vaccination during ART |

| Fear | 7 (2.39%) | Was afraid of the COVID 19 test that is done before vacation; |

| Worse COVID disease and concern of virus in vaccine | 6 (2.05%) | You get COVID Feared being injected by the virus itself whilst they pose it as a “vaccine” Feared the coronavirus being injected into him instead of actual vaccine |

| No need for vaccine/Did not want vaccine | 2 (0.68%) | |

| Social impact | 1 (0.34%) | Fear that people will gossip that am vaccinated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makadzange, A.T.; Gundidza, P.; Lau, C.; Dietrich, J.; Myburgh, N.; Elose, N.; James, W.; Stanberry, L.; Ndhlovu, C. Investigating Attitudes, Motivations and Key Influencers for COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake among Late Adopters in Urban Zimbabwe. Vaccines 2023, 11, 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020411

Makadzange AT, Gundidza P, Lau C, Dietrich J, Myburgh N, Elose N, James W, Stanberry L, Ndhlovu C. Investigating Attitudes, Motivations and Key Influencers for COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake among Late Adopters in Urban Zimbabwe. Vaccines. 2023; 11(2):411. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020411

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakadzange, Azure Tariro, Patricia Gundidza, Charles Lau, Janan Dietrich, Nellie Myburgh, Nyasha Elose, Wilmot James, Lawrence Stanberry, and Chiratidzo Ndhlovu. 2023. "Investigating Attitudes, Motivations and Key Influencers for COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake among Late Adopters in Urban Zimbabwe" Vaccines 11, no. 2: 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020411

APA StyleMakadzange, A. T., Gundidza, P., Lau, C., Dietrich, J., Myburgh, N., Elose, N., James, W., Stanberry, L., & Ndhlovu, C. (2023). Investigating Attitudes, Motivations and Key Influencers for COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake among Late Adopters in Urban Zimbabwe. Vaccines, 11(2), 411. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11020411