Abstract

Conventional vaccines are widely used to boost human natural ability to defend against foreign invaders, such as bacteria and viruses. Recently, therapeutic cancer vaccines attracted the most attention for anti-cancer therapy. According to the main components, it can be divided into five types: cell, DNA, RNA, peptide, and virus-based vaccines. They mainly perform through two rationales: (1) it trains the host immune system to protect itself and effectively eradicate cancer cells; (2) these vaccines expose the immune system to molecules associated with cancer that enable the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. In this review, we thoroughly summarized the potential strategies and technologies for developing cancer vaccines, which may provide critical achievements for overcoming the suppressive tumor microenvironment through vaccines in solid tumors.

1. Introduction

Vaccines provide a new opportunity for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. The pandemic of COVID-19 promoted the rapid development of vaccine technology and made cancer vaccines re-emerge in public focus [1]. Cancer vaccines are active immunotherapies that use nucleic acid sequences, peptides, proteins, and exosomes containing tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) or tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) to induce a specific immune response and eventually suppress tumor growth. With the successful identification of tumor antigens, personalized neoantigens vaccines and immune checkpoint inhibitors that reverse tumor-induced immune depletion, cancer vaccines have been regarded as a potentially promising therapeutic strategy in the immunotherapy of solid tumors [2]. However, the antitumor efficiency of cancer vaccines is weakened and impaired due to the highly immunosuppressive characteristics of the tumor microenvironment (TME) (Figure 1) [3,4]. In recent years, combined cancer vaccines with various immunotherapies or standardized therapies have become an effective strategy to reverse immunosuppressive TME and improve clinical outcomes [5,6]. Moreover, the availability and low cost of high-throughput sequencing technology have led to the identification of many tumor neoantigens. The in-depth research on immune mechanisms and various new vaccine platforms have widely promoted the research of cancer vaccines. In this review, we thoroughly discussed various potential tumor vaccines and its action mechanisms. Especially for solid tumors with immunosuppressive TME, we hope this review may help overcome this obstacle for cancer immunotherapy.

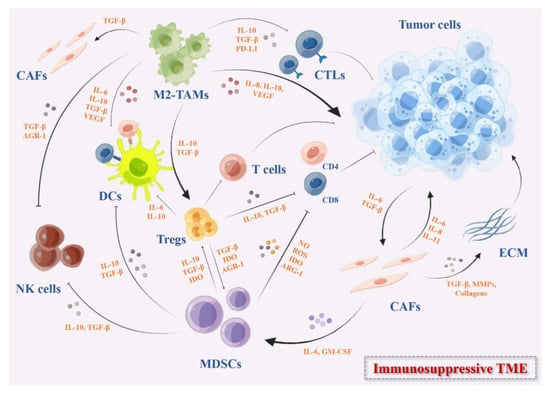

Figure 1.

The immunosuppressive TME in solid tumors. These immunosuppressive cells include MDSCs, DCs, M2-TAMs, Tregs, and CAFs. They secrete immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-10, IDO, TGF-β, growth factors such as VEGF, the checkpoints ligands such as PD-L1, or express checkpoints on the cell surface that can inhibit the activation of DC-mediated T cells and effector T cells directly or indirectly, remodel the ECM, and promote the angiogenesis in TME.

1.1. Cell-Based Cancer Vaccines

Cell-based cancer vaccines are the main form of original cancer vaccine. For instance, dendritic cell [7] is a specialized antigen-presenting cell and plays a vital role in initiating a specific T cell response in innate antitumor immunity [8]. The dendritic cell-based [7] vaccine has achieved significant results in clinical trials. It is capable of presenting cancer antigens through MHC-I and MHC-II molecules, thereby initiating an antigen-specific immune response [9,10]. The first FDA-approved DC-based vaccine Sipuleucel-T was successfully used for the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer in 2020 [11]. Studies have indicated that Sipuleucel-T prolonged the overall survival of patients with prostate cancer and reduced the risk of death [12]. Although DCs inhibit tumor growth, tumor-infiltrating DCs usually show impaired or defective function in various tumors which exacerbate immunosuppressive effects and promote tumor development [13,14]. In addition, various types of immune cells such as tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myelogenous inhibitory cells (MDSCs), and regulatory T cells (Tregs) in TME also inhibit the effector T cell response and release cytokines to affect the function of DCs [15].

To enhance the anti-cancer immune response, many DC vaccines have been prepared and loaded with various TAAs or adjuvants to development of vaccines against TME, which mainly focuses on five categories: autologous dendritic cells, autologous dendritic cells loaded with tumor lysates, autologous DC transfected or pulsed with TAA-encoded RNA, autologous DC loaded with recombinant TAAs or TAA-derived peptides, and other DCs [16]. TAA targets are expressed at high levels in different tumor cells, and the most common TAAs include MUC1, WT1, CEA, mesothelin, and mutated KRAS [17]. It is generally suggested that immature DCs induce tolerance to itself, while mature DCs resist foreign antigens and exercise immune response. Therefore, stimulating mature DCs is the primary key factor for vaccine preparation [18]. The activation of DC vaccine currently mainly adopts “mature cocktail” therapy composed of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and Toll-like receptor agonists. The monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs) exposure to a “maturation cocktail” while loaded with antigens enhances antigens capture, processing, and presentation on MHC I and MHC II molecules, increases the expression of co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, and induces DCs to initiate immature T cells [19].

The selection of appropriate antigens and antigens loading methods is crucial for DC vaccine to stimulate immune response. Common tumor antigens include tumor lysates, specific TAA-based peptides, protein, mRNA, and even whole tumor [20]. The whole tumor lysates contain a variety of tumor antigens, such as TSAs. However, other unrelated antigens are also present in the tumor lysates, resulting in decreased specificity that hinders antigens processing and presentation of DCs [21]. Peptide- or protein-based DC vaccines can reduce the incidence of autoimmune-related adverse reactions while maintaining tumor selectivity [17]. Peptides can be loaded directly onto MHC-I and MHC-II molecules on the DCs surface whereas protein and tumor cell MHC-I pathways are not specifically targeted and need to be processed and presented by DCs to induce T cells [22]. In contrast to peptide-based DC vaccines, the advantage of protein-based DC vaccines is not limited to selected haplotypes. Multiple epitopes appear on different haplotypes, thereby inducing an immune response against a broad spectrum of antigens [23]. Gene-edited DC is another effective antigen-loading method, transfecting mRNA encoding TSAs or TAAs into DCs, which avoids the need to identify haplotypes in patients and induces T cell immune response [10]. In addition, the combination of cancer vaccine with currently used cancer therapies such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and adoptive T cell therapy is an effective method to improve immunogenicity and inhibit the growth of malignant tumors.

In conclusion, vaccines provide a very promising option for anti-cancer therapy. However, the existence of immunosuppressive TME makes it difficult for the DC vaccine to exert noteworthy antitumor immunity. To further improve the efficacy, we can innovate by optimizing the DCs maturation systems, selecting the appropriate antigens, optimizing the tumor antigens loading methods, and combining with other therapies (Table 1).

Table 1.

DC-based cancer vaccines in clinical application.

1.2. DNA-Based Vaccine

DNA vaccines are now considered as a potential strategy to fight solid tumors by activating the immune system. Compared with traditional vaccines, DNA vaccines have shown great advantages in many aspects: (1) inducing both humoral immunity and cellular immunity; (2) simple and flexible design; (3) high safety, no pathogen infection risk, less adverse reactions; (4) and low cost and high production speed, and is suitable for large-scale production [24].

DNA vaccines are double-stranded nucleotides that encode a specific tumor antigen-encoding gene or immunostimulatory molecule that is transported to the host cell by a variety of delivery methods. DNA vaccines reach the cytoplasm through the cell membrane of APC and migrate to the nucleus for replication, transcription, and antigen production. The host cells express the target antigen and present the antigen through the MHC signaling pathway, thereby activating CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells and inducing immune responses [25]. DNA vaccines with built-in unmethylated CpG motif can bias the immune response to Th1, which is conducive to the induction of CTLs to kill the tumor, with a strong immune stimulation [26].

Although DNA vaccines have been shown to enhance antitumor immune responses, they are generally less immunogenic and less effective in clinical trials, primarily due to different resistance mechanisms during tumor development [27]. Therefore, optimizing the delivery system is essential to induce an effective immune response against tumor-associated antigens. The most common delivery methods of DNA vaccine are intradermal (ID) delivery and intramuscular (IM) delivery. Compared with IM delivery, ID delivery induces enhanced expression of antigens, leading to higher immunogenicity. Due to the high density of complex DCs network in dermis, the antigens are better exposed to DCs to initiate the immune response, thereby ID is the most suitable route for DNA delivery [28]. In recent years, several physical and chemical methods have been developed for DNA vaccine delivery, including gene gun delivery, electroporation, microneedles arrays, liposomes, virosomes, and nanoparticles [28,29]. Thus, optimizing the delivery system is a potential method to enhance the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines.

In addition, adjuvants are used as immunostimulatory to enhance the immunogenicity of antigens, so the development of new DNA vaccine adjuvants also significantly affects the efficacy of DNA vaccines [30]. CpG oligonucleotide (CpG ODN) activates the innate immune system and increases the number of CD8+ T cells by binding to intracellular homologous TLR-9 receptors [31]. Many cytokines that enhance cellular and humoral immune responses have been used as DNA vaccine adjuvants such as chemokines, interleukins, granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), co-stimulatory molecules, and signaling molecules to induce the immune response via Th1 and Th2 cellular pathways [32]. Studies have revealed that codon-optimized GM-CSF linked to DNA vaccine boosts IFN-γ production in specific CD8+ T cells and CD4+ T cells and polarizes Th1 immune response [33]. The plenty of DNA vaccine experiments with adjuvants have been conducted in mice or other animals, but few experiments have been conducted in human bodies, thus pending further, more in-depth research and.

In general, DNA-based vaccines have become a useful tool for the treatment of cancer. The use of adjuvants and optimization of drug delivery systems have enabled DNA vaccines to better exert the immune mechanism. In addition, DNA vaccines combined with immunosuppressive agents or other immunotherapy has become a new trend in DNA vaccines in many clinical trials (Table 2).

Table 2.

DNA-based cancer vaccines in clinical application.

1.3. RNA-Based Vaccine

The FDA approval of two kinds of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines (mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2) to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic has generated widespread interest in mRNA vaccines [34]. Similar to DNA vaccines, mRNA vaccines also induce both humoral and cellular immunity. Rationally, the mRNA encoding TSAs or TAAs enters the cytoplasm to bind with the ribosome of the host cell and translate. The antigenic proteins are degraded by the proteasome in the cytoplasm into antigenic peptides that are loaded onto MHC I for antigen-specific CD8 T cell activation. Cross-presentation of extracellular proteins on MHC I or loading onto MHC II activates CD4 T cells [35,36].

RNA vaccines have more advantages compared with DNA vaccine: mRNA is translated in splinter cells and non-splinter cells. Unlike DNA vaccines that need to migrate to the nucleus, mRNA only needs to be transferred into cytoplasm, and mRNA protein expression rate and quantity are generally higher than DNA vaccines; the mRNA vaccine is not integrated into the host genome sequence, and there is no risk of infection or insertion mutation [37,38]. However, there are some limitations in mRNA vaccines development. On the one side, the naked mRNA is rapidly degraded by extracellular RNases. On the other side, mRNA has inherent immunogenicity, which activates interferon-related reactions to further promote mRNA degradation, leading to decreased antigen expression [39].

The applications of mRNA vaccines have been limited by inefficient in vivo delivery. The mRNA are macromolecular substances that are unable to reach the cytoplasm through the lipid bilayer membrane of cell membrane, greatly limiting its clinical application. In order to solve the problem that mRNA is difficult to transmit through the cell membrane, different vectors have been developed to deliver mRNA, mainly including viral vectors, non-viral vectors, and dendritic cell-based vectors. Among many carriers, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are the most widely used delivery vehicles, which usually consist of four parts: (1) ionizable or cationic lipids for interaction with mRNA molecules; (2) auxiliary phospholipids similar to phospholipid bilayer; (3) cholesterol analog for stabilizing that LNP structure; (4) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) [40]. The ionizable lipid is a determining factor in the potency of the LNP, as it is positively charged at acidic pH and enhances the encapsulation of negatively charged mRNA by electrostatic interaction. In acidic environments, positively charged lipids interact with the ionic endosome membrane to promote membrane fusion and destabilization, resulting in mRNA release from the LNP and endosome [37]. However, ionizable lipids are essentially unchanged at physiological pH, which is a physiological property to promote endosome escape of mRNA.

A number of clinical studies have been conducted on mRNA packaged with LNP. The mRNA-4157 vaccine is a personalized mRNA vaccine encoding multiple antigens and delivering via LNP developed by Moderna in the United States [41]. Two clinical studies on the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of mRNA-4157 combined with pembrolizumab in the treatment of solid tumors are ongoing (NCT03313778/ NCT03897881). In this study, MRNA-4157 has shown remarkable safety and tolerability and induced potent antigen-specific T cell response.

Transfection of mRNA into DC was the first mRNA-based vaccine to enter clinical trials. At present, there are two delivery methods of DC-based mRNA vaccine, i.e., in vitro loaded DCs and in vivo targeted DCs. Although the procedure of ex vivo loading of DCs is complex and costly, it can achieve accurate antigen stimulation and high-efficiency transfection. DC-based mRNA vaccine is loaded in vitro by obtaining immature DCs from peripheral blood of patients, loading antigen-encoded mRNA after cells maturation, and returning to patients to initiate immune response and exert anti-cancer activity [42,43].

In a Phase I/II study, the immune response following vaccination with dendritic cells via mRNA electroporation with single-step antigen loading and TLR activation was explored in patients with stage III and IV melanoma. Participants were melanoma patients who demonstrated expression of melanoma-associated tumor antigen gp100 and tyrosinase. The results showed that intranodal administration of mRNA-optimized DC exerted great feasibility and safety, but limited TAA-specific immune response was observed (NCT01530698) [44]. In another Phase I/II trial of vaccine therapy with mRNA-transfected DCs in patients with advanced malignant melanoma, 16 of 31 patients showed tumor-specific immune responses, and the survival rate of those with responders was improved compared with non-responders. Most patients also respond to autologous DC antigens (NCT01278940) [45].

mRNA-based cancer vaccines have a broad prospect for cancer immunotherapy, but its potential has not been fully developed. With the development of nanotechnology, the use of vectors not only protects the mRNA from degradation, but also improves the immunogenicity of mRNA, making mRNA vaccine play a more effective anti-cancer mechanism. The adjustment of drug delivery routes and the combined delivery of multiple mRNA vaccines and other immunotherapeutic agents (such as checkpoint inhibitors) further improve the host antitumor immunity and increase the possibility of tumor cell eradication. Thereby, mRNA vaccine is a promising platform for cancer immunotherapy, which is expected to be rapidly developed for cancer immunotherapy in the near future (Table 3).

Table 3.

RNA-based cancer vaccines in clinical application.

1.4. Peptide-Based Cancer Vaccines

Peptide-based cancer vaccines, usually consisting of a series of amino acids derived from tumor antigen or immune activating peptide from bacteria or other hosts, offer a strong immune stimulating effect [46,47]. The peptide-based vaccine has the advantages of convenient production, high speed, low carcinogenic potential, excellent safety profiles, insusceptible pathogen contamination, high chemical stability, low cost, and easy storage [46,48]. However, peptide-based vaccines are easily degraded by enzymes and have weak immunogenicity, which are difficult to induce robust and long-term immune response.

In order to promote the immunogenicity of peptide-based vaccines, it is important to optimize the sequence length of the peptide. Short peptides, approximately 8 to 12 amino acids in length, are presented without passing through a professional APC and directly bind to MHC I molecules of APCs, resulting in temporary T cell response and immune tolerance [49,50,51]. MHC II molecules can be combined with long peptides with a length of 12–20 amino acids. The peptides are assembled into peptide–MHC II complexes, which are delivered to the cell surface to be recognized by CD4+ T helper cells, triggering a specific T cell reaction and migrating to the tumor microenvironment to play an immune mechanism to inhibit tumor growth [50,52]. Therefore, long peptide vaccines are more likely to induce sustained and effective antitumor activity responses.

The use of adjuvants protects the antigens from degradation and enhances specific immune response to antigens. TLR agonists have proven to be a promising adjuvant for peptide-based vaccines [53,54,55]. TLR is a pattern recognition receptor (PRR) that recognizes pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). TLR is able to absorb antigens and provide key cytokines to stimulate and mediate TH1 and TH17 immune responses [53]. Studies have assembled new antigenic peptide and CpG ODN to form PCNPs nanocomposites, which are capable of simultaneously delivering new antigenic peptide and adjuvant to protect CpG ODN from nuclease-mediated degradation in serum, inducing effective an antigen presentation process and activating antigen-specific T cells [53,55]. Moreover, the combination of peptide vaccine with ICIs has achieved a very significant effect on tumor regression [7,56].

Although peptide-based cancer vaccines have specific cytotoxicity to tumor cells, there are significant challenges in inducing sustained and high level of immune response. We can hopefully overcome the immunosuppressive TME of peptide-based vaccines, effectively inhibit tumor immune evasion, and enhance antitumor activity by developing multi-target vaccines, optimizing adjuvants and nanomaterials, and combining with other therapies. Generally, peptide-based therapeutic cancer vaccine, is an alternative cancer immunotherapy, and possesses great potential for clinical application in the future (Table 4).

Table 4.

Peptide-based cancer vaccines in clinical application.

1.5. Virus-Based Cancer Vaccines

Most viruses have natural immunogenicity, and their genetic material can be engineered to contain sequences encoding tumor antigens. Besides inducing local immune responses, local administration of many virus-based cancer vaccines also initiates systemic immune response, resulting in “abscopal effect”. The series of immune responses caused by virus infection eventually achieve effective and persistent antitumor immunity. Virus-based cancer vaccines are mainly divided into three forms: oncolytic virus vaccines, virus vector vaccines, and inactivated, live-attenuated or subunit vaccines against viruses that can induce tumors [57,58].

According to the report, an estimated 13% of cancers are related to viral infections in worldwide [59]. So far, hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human papillomavirus (HPV), merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV-8), human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are common carcinogenic viruses in humans [60]. These DNA and RNA viruses produce carcinogenic effects via several different distinct mechanisms [61]. At present, many types of preventive vaccines have been used for HPV and HBV in clinical trials, but they provide limited benefits for eliminating pre-existing infections [62,63,64,65]. Moreover, therapeutic vaccines are urgently required to reduce the burden of the virus-related precancerous lesions and cancers.

Viruses are commonly used as vaccine vectors for gene delivery, owing to low cost and relative ease of production, purification, and storage [57]. The main types of virus vectors are adenovirus, alphavirus, poxviral (fowlpox, canarypox (ALVAC), vaccinia virus, and modified virus Ankara), and oncolytic virus (measles virus, herpes simplex virus (HSV), and vesicular stomatitis virus). Many studies have inserted TAAs, proinflammatory cytokines (GM-CSF, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-7, IL-12, and IL-23) and chemokines into the viral genome to intensify T cell activation and augment immune cell recruitment, leading to obtain better immune stimulation effects [66,67,68].

Oncolytic viruses, as an emerging immunotherapeutic agent, are able to expressly kill tumor cells and reverse immunosuppression by modulating TME components [69]. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), as a genetically modified herpes simplex oncolytic virus, was used in a phase II study of patients with unresectable stage IIIB-IV melanoma [70]. This study revealed that T-VEC induced systemic immune activity and revised the immunosuppressive TME, thus expanding the curative effect of other immunotherapeutic drugs in combination therapy [71,72].

Despite the immunomodulatory effect of virus-based cancer therapeutic agents, there are many limitations in immunotherapy. The approaches of antitumor immunity of virus-based vaccines require further investigation to achieve systemic delivery of therapeutic agents, potentiate efficacious immune responses, and minimize immune-mediated viral clearance. Collectively, multiple virus-based cancer vaccines have built a solid basis for treating malignancies in both preclinical and clinical studies (Table 5), a new era of anti-cancer therapy on virus-based cancer vaccines is expected in clinical trials.

Table 5.

Virus-based cancer vaccines and their efficacy on the solid TME.

1.6. Novel Bioactive Nanovaccines

The clinical outcomes of cancer vaccine have been largely hampered owing to the low antigen-specific T cell response rates and acquired drug resistance caused by the immunosuppressive TME. With the increasing understanding of the immunosuppressive mechanism of TME, it is feasible to combine nano technology with cancer vaccines and many associated clinical trials are undergoing (Table 6).

Table 6.

The novel strategies of bioactive nanovaccines in immunosuppressive TME.

The application of nanotechnology to tumor vaccines has effectively enhanced the efficacy of DC vaccines. The nano vaccine consists of antigens, adjuvants, and nano carriers. A variety of nanomaterials has been used to develop and design nanovaccines, including lipid-based NPs, protein-based NPs, natural NPs, polymer NPs, and others [88]. It has been reported that the PD-1 antibody based on nanotechnology solves the problems of difficult penetration of solid tumors and high cost and enhances the antitumor activity of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells [89].

Exosomes, as a novel biological nanocarrier, efficiently transfer proteins, lipids, and RNA between cells. Compared with nanomaterials, exosomes have the advantage that they can activate innate and adaptive immunity, and have better biocompatibility, biodegradability, and safety [89,90]. Tumor-associated exosome can effectively promote DC maturation and enhance MHC cross-presentation to reduce the expression of PD-L1 [91].

Some studies have indicated that the novel treatment regimens and combined immunotherapy used in the bioactive nanovaccine platform provides a new and effective treatment strategy in the therapy of solid tumors. Recently, a pH-sensitive antitumor nanovaccine has been reported, which encapsulated colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1-R) inhibitor BLZ-945 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenaseinhibitor NLG-919 in its core and displayed a model antigen ovalbumin on its surface [7]. This nanovaccine was used to remodel the immunosuppressive TME and thus expand DCs recruitment, differentiation, antigen presentation, and T cells response [79]. TME enriches with plentiful extracellular matrix (ECM) is a compact physical barrier for the penetration of immune cells. Hyaluronan (HA) is a critical component of the ECM, which is overexpressed in various tumors and is highly related to tumor proliferation, invasion, metastasis, migration, and radiochemotherapy resistance. Studies have combined tumor nanovaccine with hyaluronidase HAase gene therapy to activate BMDCs, enhance the specific reaction of T cells in vivo, and degrade tumor ECM, thus promoting the infiltration of immune cells and modulating the immunosuppressive microenvironment [81]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), the major cells of depositing and remodeling ECM in solid tumors, have been widely described as critical actors in tumor growth, metastasis, immunosuppression, and drug resistance. Fibroblast activation protein-α (FAP) is a transmembrane serine protease and is highly expressed on CAFs in most types of tumor tissues. FAP-positive CAFs (FAPCAFs) can recruit Tregs and promote their differentiation and proliferation into Tregs in various CAFs, producing an immunosuppressive TME [92,93,94]. Some researchers prepared an FAP gene-engineered tumor cell-derived exosome-like nanovesicles (eNVs-FAP) vaccine, which not only suppressed tumor growth by enhancing the infiltration of effector T cells in tumor cells and FAPCAFs and reprogramming the immunosuppressive TME, but also facilitated IFN-γ-induced tumor cell ferroptosis [82].

At present, although tumor nanovaccines have potential applications in the prevention and treatment of solid tumors, the therapeutic effects are generally limited due to the multiple immunosuppressive TME. Thus, the combination of nanovaccines and ICIs therapies is a potential effective strategy to induce antitumor immune response in vivo and relieve tumor immune tolerance microenvironment. A multifunctional biomimetic nanovaccine based on photothermal and weak-immunostimulatory nanoparticulate cores CCM@ (PSiNPs@Au) has been reported to activate DCs and the downstream antitumor immunity. In addition, combined with ICIs immunotherapy, this nanovaccine significantly suppressed the growth and metastasis of established solid tumors through initiating antitumor immune responses and reversing immunosuppressive TME to an immunoresponsive one [83]. Studies have indicated that the combination of mannosylated nanovaccines and gene-regulated PD-L1 blockade is able to target DCs and enhance antitumor immune response, thereby improving the efficacy of tumor vaccines and inhibiting tumor growth [84]. It has been exhibited that immunogenic cell death (ICD) is capable of activating the immune microenvironment to enhance the ICIs immunotherapy efficacy [95]. Recently, a self-amplified biomimetic nanosystem, mEHGZ, was prepared by was prepared by encapsulating epirubicin (EPI), glucose oxidase (Gox), and hemin in zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) nanoparticles and coating with calreticulin (CRT) over-expressed tumor cell membrane. This mEHGZ nanovaccine amplified the ICD effect to promote DCs maturation and CTLs infiltration, thus intensifying the sensitivity of tumor cells to the treatment with anti-PD-L1 antibody [85].

Overall, these biomimetic nanoplatforms provide a novel promising method for improving the response rate of ICIs and reversing immunosuppressive TME.

2. Conclusions

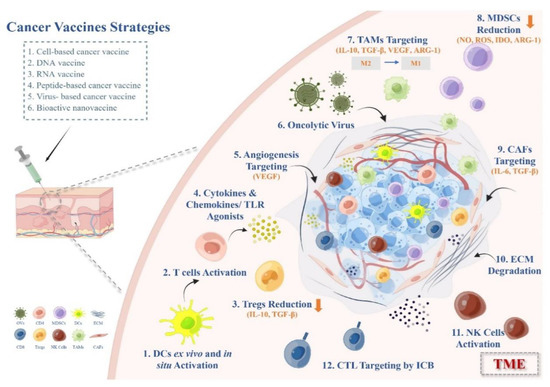

Therapeutic cancer vaccines have undergone a resurgence in the past decade. In this review, we thoroughly summarized the strategies and ideas for the exploitation of efficient cancer vaccine immunotherapy and discussed the action mechanisms and optimization of the clinical usage of distinct cancer vaccines for the treatment of solid tumors in the immunosuppressive microenvironment (Figure 2). Various types of vaccine platforms and adjuvants provide feasibility for tumor vaccine development.

Figure 2.

Therapeutic strategies of cancer vaccines overcoming immunosuppressive TME in solid tumors.

Cancer therapeutic vaccines are capable of initiating cancer-specific immune responses with minimal adverse autoimmunity, which not only induce localized immune responses, but also remodel the immunosuppressive TME, leading to the synergy with other immunotherapy methods. The aim of therapeutic cancer vaccines is to direct the immune system to induce tumor regression, eradicate minimal residual disease, establish persistent antitumor memory, and avoid non-specific or adverse reactions. However, due to the immunosuppressive properties of the TME in solid tumor, the antitumor potential of these vaccines is attenuated, posing major challenges to achieve this goal.

Finally, we discussed recent emerging bioactive nanovaccines and their therapeutic strategies in immunosuppressive TME. Nanoparticles have provided distinctive opportunities to improve the immunotherapy effect of cancer vaccines. Nanovaccines remarkably expand the immunogenicity of vaccines and boost antigen-specific adaptive immune responses for cancer therapy via effectively co-delivering multivalent molecular antigens and adjuvants to lymphoid tissues and immune cells. Bioactive nanovaccines are prospective to maximize the potential of cancer vaccines in solid tumor and provide a very promising strategy for elevating the response rate of ICIs and reversing immunosuppressive TME.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-J.X., W.-Q.L. and X.-X.F.; formal analysis, Y.-J.X., W.-Q.L., D.L. and J.-C.H.; investigation, Y.-J.X. and W.-Q.L.; data curation, Y.-J.X., D.L. and J.-C.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-J.X. and W.-Q.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.-J.X., X.-X.F. and P.S.C.; visualization, Y.-J.X., W.-Q.L. and X.-X.F.; supervision, X.-X.F. and P.S.C.; project administration, X.-X.F. and P.S.C.; funding acquisition, X.-X.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Macau Science and Technology Development Fund project granted to Dr. Xing-Xing Fan (Grant no. 0003/2018/A1 and 0058/2020/A2) and Dr. Neher’s Biophysics Laboratory for Innovative Drug Discovery (Grant no. 001/2020/ALC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Figures were created by Figdraw.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| TSAs | tumor-specific antigens |

| TAAs | tumor-associated antigens |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| DC | dendritic cell |

| TAMs | tumor-associated macrophages |

| MDSCs | myelogenous inhibitory cells |

| Tregs | regulatory T cells |

| MoDCs | monocyte-derived DCs |

| ICIs | immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| ID | intradermal |

| IM | intramuscular |

| CpG ODN | CpG oligonucleotide |

| GM-CSF | granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| LNP | lipid nanoparticles |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| PRR | pattern recognition receptor |

| PAMP | pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| HBV | hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | hepatitis C virus |

| HPV | human papillomavirus |

| MCV | merkel cell polyomavirus |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| HHV-8 | human herpesvirus type 8 |

| HTLV-1 | human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1 |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| HSV | herpes simplex virus |

| T-VEC | talimogene laherparepvec |

| CSF1-R | colony stimulating factor 1 receptor |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| HA | hyaluronan |

| CAFs | cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| FAP | fibroblast activation protein-α |

| FAPCAFs | FAP-positive CAFs |

| eNVs-FAP | FAP gene-engineered tumor cell-derived exosome-like nanovesicles |

| ICD | immunogenic cell death |

| EPI | encapsulating epirubicin |

| Gox | glucose oxidase |

| ZIF-8 | hemin in zeolitic imidazolate framework |

| CRT | calreticulin |

References

- Jhaveri, R. The COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines and the Pandemic: Do They Represent the Beginning of the End or the End of the Beginning? Clin. Ther. 2021, 43, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Wahi, A.; Sharma, P.; Nagpal, R.; Raina, N.; Kaurav, M.; Bhattacharya, J.; Rodrigues Oliveira, S.M.; Dolma, K.G.; Paul, A.K.; et al. Recent Advances in Cancer Vaccines: Challenges, Achievements, and Futuristic Prospects. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.; Patel, S.; Tcyganov, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. The Nature of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016, 37, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, Y.; Tang, F.; Wei, Y.Q.; Wei, X.W. Immunosuppressive cells in cancer: Mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.G.; Sang, Y.B.; Lee, J.H.; Chon, H.J. Combining Cancer Vaccines with Immunotherapy: Establishing a New Immunological Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Durden, D.L. Combinatorial Approach to Improve Cancer Immunotherapy: Rational Drug Design Strategy to Simultaneously Hit Multiple Targets to Kill Tumor Cells and to Activate the Immune System. J. Oncol. 2019, 2019, 5245034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, G.T.; Kudchadkar, R.R.; DeConti, R.C.; Thebeau, M.S.; Czupryn, M.P.; Tetteh, L.; Eysmans, C.; Richards, A.; Schell, M.J.; Fisher, K.J.; et al. Safety, correlative markers, and clinical results of adjuvant nivolumab in combination with vaccine in resected high-risk metastatic melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, G.J. Dendritic cells: The first step. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20202077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildner, A.; Jung, S. Development and function of dendritic cell subsets. Immunity 2014, 40, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldin, A.V.; Savvateeva, L.V.; Bazhin, A.V.; Zamyatnin, A.A., Jr. Dendritic Cells in Anticancer Vaccination: Rationale for Ex Vivo Loading or In Vivo Targeting. Cancers 2020, 12, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, C.E.; Antonarakis, E.S. Sipuleucel-T for the treatment of prostate cancer: Novel insights and future directions. Future Oncol. 2018, 14, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantoff, P.W.; Higano, C.S.; Shore, N.D.; Berger, E.R.; Small, E.J.; Penson, D.F.; Redfern, C.H.; Ferrari, A.C.; Dreicer, R.; Sims, R.B.; et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shurin, G.V.; Peiyuan, Z.; Shurin, M.R. Dendritic cells in the cancer microenvironment. J. Cancer 2013, 4, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Jiang, A. Dendritic Cells and CD8 T Cell Immunity in Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohue, Y.; Nishikawa, H. Regulatory T (Treg) cells in cancer: Can Treg cells be a new therapeutic target? Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 2080–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureano, R.S.; Sprooten, J.; Vanmeerbeerk, I.; Borras, D.M.; Govaerts, J.; Naulaerts, S.; Berneman, Z.N.; Beuselinck, B.; Bol, K.F.; Borst, J.; et al. Trial watch: Dendritic cell (DC)-based immunotherapy for cancer. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2096363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Shangguan, J.; Eresen, A.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z. Dendritic cells in pancreatic cancer immunotherapy: Vaccines and combination immunotherapies. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis e Sousa, C. Dendritic cells in a mature age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Baldwin, J.; Brar, D.; Salunke, D.B.; Petrovsky, N. Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists as a driving force behind next-generation vaccine adjuvants and cancer therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2022, 70, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprooten, J.; Ceusters, J.; Coosemans, A.; Agostinis, P.; De Vleeschouwer, S.; Zitvogel, L.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L.; Garg, A.D. Trial watch: Dendritic cell vaccination for cancer immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2019, 8, e1638212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, L.; Jia, M.; Liao, Q.; Peng, G.; Luo, G.; Zhou, Y. Dendritic cell vaccines improve the glioma microenvironment: Influence, challenges, and future directions. Cancer Med. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantino, J.; Gomes, C.; Falcao, A.; Neves, B.M.; Cruz, M.T. Dendritic cell-based immunotherapy: A basic review and recent advances. Immunol. Res. 2017, 65, 798–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabado, R.L.; Bhardwaj, N. Directing dendritic cell immunotherapy towards successful cancer treatment. Immunotherapy 2010, 2, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Jeang, J.; Yang, A.; Wu, T.C.; Hung, C.F. DNA vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2014, 10, 3153–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellios, N.; van der Zee, K. Dataset on cigarette smokers in six South African townships. Data Brief 2020, 32, 106260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z. DNA vaccine. Adv. Genet. 2005, 54, 257–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.; Vandermeulen, G.; Preat, V. Cancer DNA vaccines: Current preclinical and clinical developments and future perspectives. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorritsma, S.H.T.; Gowans, E.J.; Grubor-Bauk, B.; Wijesundara, D.K. Delivery methods to increase cellular uptake and immunogenicity of DNA vaccines. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5488–5494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eusebio, D.; Neves, A.R.; Costa, D.; Biswas, S.; Alves, G.; Cui, Z.; Sousa, A. Methods to improve the immunogenicity of plasmid DNA vaccines. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 2575–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiptiri-Kourpeti, A.; Spyridopoulou, K.; Pappa, A.; Chlichlia, K. DNA vaccines to attack cancer: Strategies for improving immunogenicity and efficacy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 165, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, C.; Zhao, G.; Steinhagen, F.; Kinjo, T.; Klinman, D.M. CpG DNA as a vaccine adjuvant. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2011, 10, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P.; Lin, C.C.; Xie, Y.X.; Chen, C.Y.; Qiu, J.T. Enhancing immunogenicity of HPV16 E(7) DNA vaccine by conjugating codon-optimized GM-CSF to HPV16 E(7) DNA. Taiwan J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 60, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.C.; Wijesundara, D.K.; Masavuli, M.G.; Mekonnen, Z.A.; Gowans, E.J.; Grubor-Bauk, B. Cytolytic Perforin as an Adjuvant to Enhance the Immunogenicity of DNA Vaccines. Vaccines 2019, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, C.; Sharma, A.R.; Bhattacharya, M.; Lee, S.S. From COVID-19 to Cancer mRNA Vaccines: Moving from Bench to Clinic in the Vaccine Landscape. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 679344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yang, K.; Li, R.; Zhang, L. mRNA Vaccine Era-Mechanisms, Drug Platform and Clinical Prospection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, C.L.; Haanen, J.B.; Met, O.; Svane, I.M. Clinical advances and ongoing trials on mRNA vaccines for cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, e450–e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L. mRNA vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, T. Nanoparticle-Mediated Cytoplasmic Delivery of Messenger RNA Vaccines: Challenges and Future Perspectives. Pharm. Res. 2021, 38, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S.; Satapathy, S.R.; Dutta, T. Delivery Strategies for mRNA Vaccines. Pharmaceut. Med. 2022, 36, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, A.J.; Jiang, A.Y.; Zhang, P.; Wooster, R.; Anderson, D.G. The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 840–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- mRNA-4157 Cancer Vaccine. Available online: https://www.precisionvaccinations.com/vaccines/mrna-4157-cancer-vaccine (accessed on 5 November 2021).

- Bidram, M.; Zhao, Y.; Shebardina, N.G.; Baldin, A.V.; Bazhin, A.V.; Ganjalikhany, M.R.; Zamyatnin, A.A., Jr.; Ganjalikhani-Hakemi, M. mRNA-Based Cancer Vaccines: A Therapeutic Strategy for the Treatment of Melanoma Patients. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, P.S.; Rudra, A.; Miao, L.; Anderson, D.G. Delivering the Messenger: Advances in Technologies for Therapeutic mRNA Delivery. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bol, K.F.; Figdor, C.G.; Aarntzen, E.H.; Welzen, M.E.; van Rossum, M.M.; Blokx, W.A.; van de Rakt, M.W.; Scharenborg, N.M.; de Boer, A.J.; Pots, J.M.; et al. Intranodal vaccination with mRNA-optimized dendritic cells in metastatic melanoma patients. Oncoimmunology 2015, 4, e1019197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyte, J.A.; Aamdal, S.; Dueland, S.; Saeboe-Larsen, S.; Inderberg, E.M.; Madsbu, U.E.; Skovlund, E.; Gaudernack, G.; Kvalheim, G. Immune response and long-term clinical outcome in advanced melanoma patients vaccinated with tumor-mRNA-transfected dendritic cells. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1232237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tang, H.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Yu, Z.; Li, J. Peptide-based therapeutic cancer vaccine: Current trends in clinical application. Cell Prolif. 2021, 54, e13025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Aziz, N.; Poh, C.L. Development of Peptide-Based Vaccines for Cancer. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 9749363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skwarczynski, M.; Toth, I. Peptide-based synthetic vaccines. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijker, M.S.; van den Eeden, S.J.; Franken, K.L.; Melief, C.J.; Offringa, R.; van der Burg, S.H. CD8 + CTL priming by exact peptide epitopes in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant induces a vanishing CTL response, whereas long peptides induce sustained CTL reactivity. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 5033–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, K.; Yin, H.; Zheng, J.N. Composite peptide-based vaccines for cancer immunotherapy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 35, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonneuve, C.; Bertholet, S.; Philpott, D.J.; de Gregorio, E. Unleashing the potential of NOD- and Toll-like agonists as vaccine adjuvants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 12294–12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fan, J.; Skwarczynski, M.; Stephenson, R.J.; Toth, I.; Hussein, W.M. Peptide-Based Nanovaccines in the Treatment of Cervical Cancer: A Review of Recent Advances. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 869–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Cui, X.; Yang, L.; Hu, Q.; Li, D.; Zhang, X.; Han, L.; Shi, S.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, W.; et al. Co-assembled nanocomplexes of peptide neoantigen Adpgk and Toll-like receptor 9 agonist CpG ODN for efficient colorectal cancer immunotherapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 608, 121091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammi, R.; de Waele, J.; Willemen, Y.; van Brussel, I.; Schrijvers, D.M.; Lion, E.; Smits, E.L. Poly(I:C) as cancer vaccine adjuvant: Knocking on the door of medical breakthroughs. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 146, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, Y.; Iguchi, T.; Matsui, H.; Adachi, K.; Sakoda, Y.; Miyakawa, T.; Doi, S.; Hazama, S.; Nagano, H.; Ueyama, Y.; et al. Combined adjuvants of poly(I:C) plus LAG-3-Ig improve antitumor effects of tumor-specific T cells, preventing their exhaustion. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Wada, H.; Goto, R.; Osada, T.; Yamamura, K.; Fukaya, S.; Shimizu, A.; Okubo, M.; Minamiguchi, K.; Ikizawa, K.; et al. TAS0314, a novel multi-epitope long peptide vaccine, showed synergistic antitumor immunity with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in HLA-A*2402 mice. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocca, C.; Schlom, J. Viral vector-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Cancer J. 2011, 17, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.S.; Lu, B.; Guo, Z.; Giehl, E.; Feist, M.; Dai, E.; Liu, W.; Storkus, W.J.; He, Y.; Liu, Z.; et al. Vaccinia virus-mediated cancer immunotherapy: Cancer vaccines and oncolytics. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martel, C.; Georges, D.; Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Clifford, G.M. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e180–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, M.; de Martel, C.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Franceschi, S. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: A synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e609–e616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, H.; Brenner, M.K. Immunotherapy against cancer-related viruses. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielska, U.; Nowinska, K.; Podhorska-Okolow, M.; Dziegiel, P. The role of human papillomavirus in the malignant transformation of cervix epithelial cells and the importance of vaccination against this virus. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2012, 21, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Pan, W.; Jin, L.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Wu, D.; Gao, C.; Ma, D.; Liao, S. Human papillomavirus vaccine against cervical cancer: Opportunity and challenge. Cancer Lett. 2020, 471, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattyn, J.; Hendrickx, G.; Vorsters, A.; van Damme, P. Hepatitis B Vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 224, S343–S351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glebe, D.; Goldmann, N.; Lauber, C.; Seitz, S. HBV evolution and genetic variability: Impact on prevention, treatment and development of antivirals. Antivir. Res. 2021, 186, 104973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.F.; Qi, W.X.; Liu, M.Y.; Li, Y. The combination of NK and CD8+T cells with CCL20/IL15-armed oncolytic adenoviruses enhances the growth suppression of TERT-positive tumor cells. Cell Immunol. 2017, 318, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Ye, J.; Ge, Y.; Wang, H.; Dai, E.; Ren, J.; Liu, W.; Ma, C.; Ju, S.; et al. Intratumoral expression of interleukin 23 variants using oncolytic vaccinia virus elicit potent antitumor effects on multiple tumor models via tumor microenvironment modulation. Theranostics 2021, 11, 6668–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, S.; Arai, Y.; Tasaki, M.; Yamashita, M.; Murakami, R.; Kawase, T.; Amino, N.; Nakatake, M.; Kurosaki, H.; Mori, M.; et al. Intratumoral expression of IL-7 and IL-12 using an oncolytic virus increases systemic sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaax7992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Qian, L.; Wang, P. Oncolytic virotherapy reverses the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and its potential in combination with immunotherapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andtbacka, R.H.; Kaufman, H.L.; Collichio, F.; Amatruda, T.; Senzer, N.; Chesney, J.; Delman, K.A.; Spitler, L.E.; Puzanov, I.; Agarwala, S.S.; et al. Talimogene Laherparepvec Improves Durable Response Rate in Patients with Advanced Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2780–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Puzanov, I.; Kelley, M.C. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) for the treatment of advanced melanoma. Immunotherapy 2015, 7, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommareddy, P.K.; Patel, A.; Hossain, S.; Kaufman, H.L. Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC) and Other Oncolytic Viruses for the Treatment of Melanoma. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2017, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, P.F.; Pala, L.; Conforti, F.; Cocorocchio, E. Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-VEC): An Intralesional Cancer Immunotherapy for Advanced Melanoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semmrich, M.; Marchand, J.B.; Fend, L.; Rehn, M.; Remy, C.; Holmkvist, P.; Silvestre, N.; Svensson, C.; Kleinpeter, P.; Deforges, J.; et al. Vectorized Treg-depleting alphaCTLA-4 elicits antigen cross-presentation and CD8(+) T cell immunity to reject ‘cold’ tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ju, F.; Luo, Y.; Lin, C.; Jia, X.; Xu, Z.; Tian, R.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chang, Y.; Huang, X.; et al. Oncolytic virus expressing PD-1 inhibitors activates a collaborative intratumoral immune response to control tumor and synergizes with CTLA-4 or TIM-3 blockade. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draghiciu, O.; Boerma, A.; Hoogeboom, B.N.; Nijman, H.W.; Daemen, T. A rationally designed combined treatment with an alphavirus-based cancer vaccine, sunitinib and low-dose tumor irradiation completely blocks tumor development. Oncoimmunology 2015, 4, e1029699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellom, S.T.; Smalley Rumfield, C.; Morillon, Y.M., 2nd; Roller, N.; Poppe, L.K.; Brough, D.E.; Sabzevari, H.; Schlom, J.; Jochems, C. Characterization of recombinant gorilla adenovirus HPV therapeutic vaccine PRGN-2009. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e141912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, E.J.; Gwin, W.; Blackwell, K.; Marcom, P.K.; Chang, S.; Maecker, H.T.; Broadwater, G.; Hyslop, T.; Kim, S.; Rogatko, A.; et al. Vaccine-Induced Memory CD8(+) T Cells Provide Clinical Benefit in HER2 Expressing Breast Cancer: A Mouse to Human Translational Study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2725–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Su, Q.; Song, T.; Yang, G.; Li, N.; Wei, X.; Li, T.; Qin, X.; et al. Remodeling tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment via a novel bioactive nanovaccines potentiates the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 16, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Wu, T.; Lan, S.; Liu, C.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, W. In situ photothermal nano-vaccine based on tumor cell membrane-coated black phosphorus-Au for photo-immunotherapy of metastatic breast tumors. Biomaterials 2022, 289, 121808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lin, L.; Chen, J.; Maruyama, A.; Tian, H.; Chen, X. Synergistic tumor immunological strategy by combining tumor nanovaccine with gene-mediated extracellular matrix scavenger. Biomaterials 2020, 252, 120114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ma, J.; Su, C.; Chen, Y.; Shu, Y.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, B.; Shi, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Engineered exosome-like nanovesicles suppress tumor growth by reprogramming tumor microenvironment and promoting tumor ferroptosis. Acta Biomater. 2021, 135, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, D.; Cheng, R.; Figueiredo, P.; Fontana, F.; Correia, A.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Kemell, M.; Torrieri, G.; et al. Multifunctional Biomimetic Nanovaccines Based on Photothermal and Weak-Immunostimulatory Nanoparticulate Cores for the Immunotherapy of Solid Tumors. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, e2108012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fang, H.; Hu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Feng, Y.; Lin, L.; Tian, H.; Chen, X. Combining mannose receptor mediated nanovaccines and gene regulated PD-L1 blockade for boosting cancer immunotherapy. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 7, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Cai, H.; Li, Z.; Ren, L.; Ma, X.; Zhu, H.; Gong, Q.; Zhang, H.; Gu, Z.; Luo, K. A tumor cell membrane-coated self-amplified nanosystem as a nanovaccine to boost the therapeutic effect of anti-PD-L1 antibody. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 21, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chen, G.; Xiao, Z.; Li, B.; Zhong, H.; Lin, M.; Cai, Y.; Huang, J.; Xie, X.; Shuai, X. Surgical Tumor-Derived Photothermal Nanovaccine for Personalized Cancer Therapy and Prevention. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 3095–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wu, J.; Feng, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, T.; Meng, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Tian, H. CD47KO/CRT dual-bioengineered cell membrane-coated nanovaccine combined with anti-PD-L1 antibody for boosting tumor immunotherapy. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 22, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad, H.; Saleh Ibrahim, Y.; Mohammed Al-Taee, M.; Gabr, G.A.; Waheed Riaz, M.; Hamoud Alshahrani, S.; Alexis Ramirez-Coronel, A.; Turki Jalil, A.; Setia Budi, H.; Sawitri, W.; et al. Nanovaccines in cancer immunotherapy: Focusing on dendritic cell targeting. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 113, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Yang, X.; Xie, S.; Zhong, D.; Lin, X.; Ding, Z.; Duan, S.; Mo, F.; Liu, A.; Yin, S.; et al. A new PD-1-specific nanobody enhances the antitumor activity of T-cells in synergy with dendritic cell vaccine. Cancer Lett. 2021, 522, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Miao, Y.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Dai, J. Recent progress of dendritic cell-derived exosomes (Dex) as an anti-cancer nanovaccine. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 152, 113250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huang, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Guo, G. Tumor Cell-associated Exosomes Robustly Elicit Anti-tumor Immune Responses through Modulating Dendritic Cell Vaccines in Lung Tumor. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshio, Y.; Teramoto, K.; Hanaoka, J.; Tezuka, N.; Itoh, Y.; Asai, T.; Daigo, Y.; Ogasawara, K. Cancer-associated fibroblast-targeted strategy enhances antitumor immune responses in dendritic cell-based vaccine. Cancer Sci. 2015, 106, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Research Progress on Therapeutic Targeting of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts to Tackle Treatment-Resistant NSCLC. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhaidly, R.; Mechta-Grigoriou, F. Fibroblast heterogeneity in tumor micro-environment: Role in immunosuppression and new therapies. Semin. Immunol. 2020, 48, 101417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Lai, X.; Fu, S.; Ren, L.; Cai, H.; Zhang, H.; Gu, Z.; Ma, X.; Luo, K. Immunogenic Cell Death Activates the Tumor Immune Microenvironment to Boost the Immunotherapy Efficiency. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, e2201734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).