Clinical Utility of SARS-CoV-2 Serological Testing and Defining a Correlate of Protection

Abstract

:1. Background

1.1. Antigenic Specificity

1.2. The Precedent of an Antibody CoP for Other Viruses, and Lessons Learned

“Antibody tests with very high sensitivity and specificity are preferred since they are more likely to exhibit high positive (probability that the person testing positive actually has antibodies) and negative predictive values (probability that the person testing negative actually does not have antibodies) when administered at least 3 weeks after the onset of illness.Additional considerations when selecting an antibody test include:

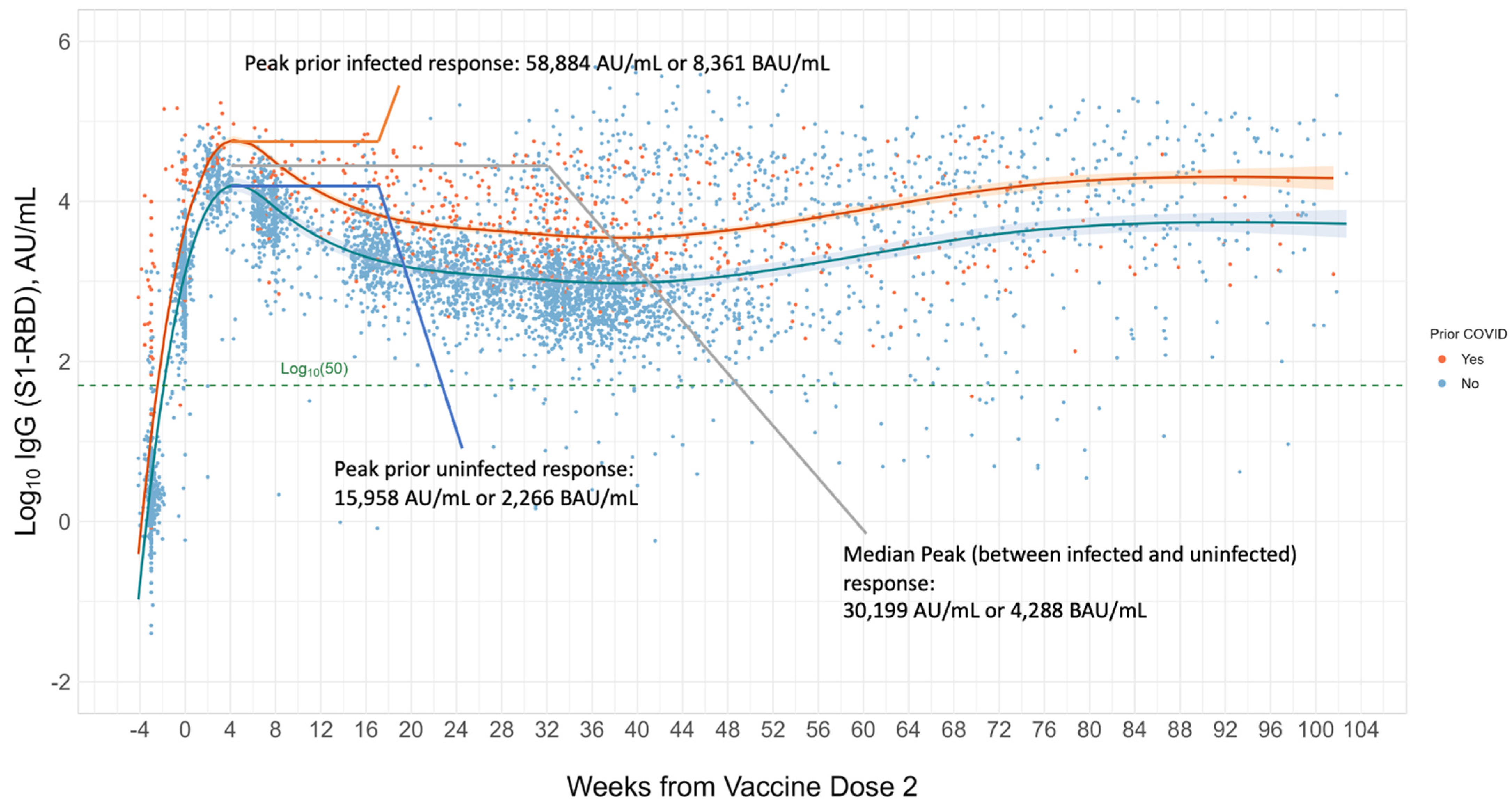

2. SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Levels in Immunocompetent Individuals

Establishing a Serological Correlate of Protection (CoP) and the Issue of Variants

3. Established and Developing SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Clinical Use Cases

3.1. Diagnosis of Prior Recent Infection

3.2. Convalescent Plasma (When Therapeutics Will Not Work against Variants)

3.3. MIS-C

3.4. Booster Doses in Immunosuppressed Populations

3.5. Routine Booster Dosing, Updated Vaccines, and General Population Antibody Response

4. Limitations of Serology Testing

4.1. Timing and Lack of Standardization

4.2. Impact of Variants on the Antibody Response

4.3. A Consideration of the Cellular Response

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satarker, S.; Nampoothiri, M. Structural Proteins in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2. Arch. Med. Res. 2020, 51, 482–491. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, X.; Yan, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, P.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. A neutralizing human antibody binds to the N-terminal domain of the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science 2020, 369, 650–655. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, S.; Wang, P. Broadly neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 189–199. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, D.; Sauer, M.M.; Czudnochowski, N.; Low, J.S.; Tortorici, M.A.; Housley, M.P.; Noack, J.; Walls, A.C.; Bowen, J.E.; Guarino, B.; et al. Broad betacoronavirus neutralization by a stem helix-specific human antibody. Science 2021, 373, 1109–1116. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacon, C.; Tucker, C.; Peng, L.; Lee, C.D.; Lin, T.H.; Yuan, M.; Cong, Y.; Wang, L.; Purser, L.; Williams, J.K.; et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies target the coronavirus fusion peptide. Science 2022, 377, 728–735. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.S.; Jerak, J.; Tortorici, M.A.; McCallum, M.; Pinto, D.; Cassotta, A.; Foglierini, M.; Mele, F.; Abdelnabi, R.; Weynand, B.; et al. ACE2-binding exposes the SARS-CoV-2 fusion peptide to broadly neutralizing coronavirus antibodies. Science 2022, 377, 735–742. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, J.; Windau, A.; Schmotzer, C.; Saade, E.; Noguez, J.; Stempak, L.; Zhang, X. SARS-CoV-2 antibody profile of naturally infected and vaccinated individuals detected using qualitative, semi-quantitative and multiplex immunoassays. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2022, 104, 115803. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, L.B.; Tedla, N.; Bull, R.A. Broadly-Neutralizing Antibodies Against Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 752003. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Chang, S.C. SARS-CoV-2 spike S2-specific neutralizing antibodies. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2023, 12, 2220582. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.W.; Faulkner, N.; Finsterbusch, K.; Wu, M.; Harvey, R.; Hussain, S.; Greco, M.; Liu, Y.; Kjaer, S.; Swanton, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 S2-targeted vaccination elicits broadly neutralizing antibodies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabn3715. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfmann, P.J.; Frey, S.J.; Loeffler, K.; Kuroda, M.; Maemura, T.; Armbrust, T.; Yang, J.E.; Hou, Y.J.; Baric, R.; Wright, E.R.; et al. Multivalent S2-based vaccines provide broad protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and pangolin coronaviruses. EBioMedicine 2022, 86, 104341. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Y.B.; Shen, F.; Fan, C.F.; Wang, Q.; He, W.Q.; He, X.Y.; Li, Z.K.; Chen, T.T.; et al. A variant-proof SARS-CoV-2 vaccine targeting HR1 domain in S2 subunit of spike protein. Cell Res. 2022, 32, 1068–1085. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, N.; Singh, R.; Dar, Z.; Bijarnia, R.K.; Dhingra, N.; Kaur, T. Genetic comparison among various coronavirus strains for the identification of potential vaccine targets of SARS-CoV2. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2021, 89, 104490. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J. The SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Its Role in Viral Structure, Biological Functions, and a Potential Target for Drug or Vaccine Mitigation. Viruses 2021, 13, 1115. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naqvi, A.A.T.; Fatima, K.; Mohammad, T.; Fatima, U.; Singh, I.K.; Singh, A.; Atif, S.M.; Hariprasad, G.; Hasan, G.M.; Hassan, M.I. Insights into SARS-CoV-2 genome, structure, evolution, pathogenesis and therapies: Structural genomics approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165878. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Y.; Wang, K.; Qiu, S.; Lu, K.; Liu, Y. Comparing the Nucleocapsid Proteins of Human Coronaviruses: Structure, Immunoregulation, Vaccine, and Targeted Drug. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 761173. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Elslande, J.; Gruwier, L.; Godderis, L.; Vermeersch, P. Estimated Half-Life of SARS-CoV-2 Anti-Spike Antibodies More Than Double the Half-Life of Anti-nucleocapsid Antibodies in Healthcare Workers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 2366–2368. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, L.; Segovia-Chumbez, B.; Jadi, R.; Martinez, D.R.; Raut, R.; Markmann, A.; Cornaby, C.; Bartelt, L.; Weiss, S.; Park, Y.; et al. The receptor binding domain of the viral spike protein is an immunodominant and highly specific target of antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 patients. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eabc8413. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDSA. Antibody Testing. Available online: https://www.idsociety.org/covid-19-real-time-learning-network/diagnostics/antibody-testing/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- US FDA. EUA Authorized Serology Test Performance. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/eua-authorized-serology-test-performance (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Gilbert, P.B.; Montefiori, D.C.; McDermott, A.B.; Fong, Y.; Benkeser, D.; Deng, W.; Zhou, H.; Houchens, C.R.; Martins, K.; Jayashankar, L.; et al. Immune correlates analysis of the mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Science 2022, 375, 43–50. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Phillips, D.J.; White, T.; Sayal, H.; Aley, P.K.; Bibi, S.; Dold, C.; Fuskova, M.; Gilbert, S.C.; Hirsch, I.; et al. Correlates of protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 2032–2040. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Benkeser, D.; Carpp, L.N.; Áñez, G.; Woo, W.; McGarry, A.; Dunkle, L.M.; Cho, I.; Houchens, C.R.; et al. Immune Correlates Analysis of the PREVENT-19 COVID-19 Vaccine Efficacy Clinical Trial. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Y.; McDermott, A.B.; Benkeser, D.; Roels, S.; Stieh, D.J.; Vandebosch, A.; Le Gars, M.; Van Roey, G.A.; Houchens, C.R.; Martins, K.; et al. Immune correlates analysis of the ENSEMBLE single Ad26.COV2.S dose vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1996–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, L.M.; Kotloff, K.L.; Gay, C.L.; Áñez, G.; Adelglass, J.M.; Barrat Hernández, A.Q.; Harper, W.L.; Duncanson, D.M.; McArthur, M.A.; Florescu, D.F.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of NVX-CoV2373 in Adults in the United States and Mexico. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 386, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Benkeser, D.; Carpp, L.N.; Áñez, G.; Woo, W.; McGarry, A.; Dunkle, L.M.; Cho, I.; Houchens, C.R.; et al. Immune correlates analysis of the PREVENT-19 COVID-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 331. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeba, E.; Krashias, G.; Constantinou, A.; Koptides, D.; Lambrianides, A.; Christodoulou, C. Evaluation of S1RBD-Specific IgG Antibody Responses following COVID-19 Vaccination in Healthcare Professionals in Cyprus: A Comparative Look between the Vaccines of Pfizer-BioNTech and AstraZeneca. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 967. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, F.; Silva, D.; Pérez Bogado, J.A.; Rangel, H.R.; de Waard, J.H. Lasting SARS-CoV-2 specific IgG Antibody response in health care workers from Venezuela, 6 months after vaccination with Sputnik, V. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 122, 850–854. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordi, L.; Sberna, G.; Piscioneri, C.N.; Cocchiara, R.A.; Miani, A.; Grammatico, P.; Mariani, B.; Parisi, G. Longitudinal dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 anti-receptor binding domain IgG antibodies in a wide population of health care workers after BNT162b2 vaccination. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 122, 174–177. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Sasso, B.; Giglio, R.V.; Vidali, M.; Scazzone, C.; Bivona, G.; Gambino, C.M.; Ciaccio, A.M.; Agnello, L.; Ciaccio, M. Evaluation of Anti-SARS-Cov-2 S-RBD IgG Antibodies after COVID-19 mRNA BNT162b2 Vaccine. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1135. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, L.; Andrée, M.; Moskorz, W.; Drexler, I.; Walotka, L.; Grothmann, R.; Ptok, J.; Hillebrandt, J.; Ritchie, A.; Rabl, D.; et al. Age-dependent Immune Response to the Biontech/Pfizer BNT162b2 Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 2065–2072. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajanova, I.; Radikova, Z.; Lukacikova, L.; Jelenska, L.; Grossmannova, K.; Belisova, M.; Kopacek, J.; Pastorekova, S. Study of anti-S1-protein IgG antibody levels as potential correlates of protection against breakthrough infection with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 variants. Acta Virol. 2023, 67, 11652. (Brief Research Report) (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interim Guidelines for COVID-19 Antibody Testing, CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antibody-tests-guidelines.html#anchor_1616006658343 (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- McMenamin, M.E.; Nealon, J.; Lin, Y.; Wong, J.Y.; Cheung, J.K.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Wu, P.; Leung, G.M.; Cowling, B.J. Vaccine effectiveness of one, two, and three doses of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac against COVID-19 in Hong Kong: A population-based observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1435–1443. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.V.; Wiencek, J.; Meng, Q.H.; Theel, E.S.; Babic, N.; Sepiashvili, L.; Pecora, N.D.; Slev, P.; Cameron, A.; Konforte, D.; et al. AACC Practical Recommendations for Implementing and Interpreting SARS-CoV-2 Emergency Use Authorization and Laboratory-Developed Test Serologic Testing in Clinical Laboratories. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 1188–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrag, S.J.; Rota, P.A.; Bellini, W.J. Spontaneous mutation rate of measles virus: Direct estimation based on mutations conferring monoclonal antibody resistance. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 51–54. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulton, B.O.; Sachs, D.; Beaty, S.M.; Won, S.T.; Lee, B.; Palese, P.; Heaton, N.S. Mutational Analysis of Measles Virus Suggests Constraints on Antigenic Variation of the Glycoproteins. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 1331–1338. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Alía, M.; Nace, R.A.; Zhang, L.; Russell, S.J. Serotypic evolution of measles virus is constrained by multiple co-dominant B cell epitopes on its surface glycoproteins. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100225. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Selecting Viruses for the Seasonal Influenza Vaccine. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/vaccine-selection.htm (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Nobusawa, E.; Sato, K. Comparison of the mutation rates of human influenza A and B viruses. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 3675–3678. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, V.N.; Russell, C.A. The evolution of seasonal influenza viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 47–60. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillie, S.; Murphy, T.V.; Sawyer, M.; Ly, K.; Hughes, E.; Ruth, J.; de Perio, M.A.; Reilly, M.; Byrd, K.; Ward, J.W. CDC Guidance for Evaluating Health-Care Personnel for Hepatitis B Virus Protection and for Administering Postexposure Management. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. (MMWR) 2013, 62, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mast, E.E.; Margolis, H.S.; Fiore, A.E.; Brink, E.W.; Goldstein, S.T.; Wang, S.A.; Moyer, L.A.; Bell, B.P.; Alter, M.J. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) part 1: Immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2005, 54, 1–31. (In English) [Google Scholar]

- Jack, A.D.; Hall, A.J.; Maine, N.; Mendy, M.; Whittle, H.C. What level of hepatitis B antibody is protective? J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 179, 489–492. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleman, A.B.; Baker, C.J.; Kozinetz, C.A.; Kamili, S.; Nguyen, C.; Hu, D.J.; Spradling, P.R. Duration of protection after infant hepatitis B vaccination series. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e1500–e1507. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Damme, P. Long-term Protection After Hepatitis B Vaccine. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 1–3. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuridan, E.; Van Damme, P. Hepatitis B and the need for a booster dose. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 68–75. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, O.W.; Chia, A.; Tan, A.T.; Jadi, R.S.; Leong, H.N.; Bertoletti, A.; Tan, Y.J. Memory T cell responses targeting the SARS coronavirus persist up to 11 years post-infection. Vaccine 2016, 34, 2008–2014. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bert, N.; Tan, A.T.; Kunasegaran, K.; Tham, C.Y.L.; Hafezi, M.; Chia, A.; Chng, M.H.Y.; Lin, M.; Tan, N.; Linster, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immunity in cases of COVID-19 and SAR.S.; and uninfected controls. Nature 2020, 584, 457–462. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, S.; Schwarz, T.; Corman, V.M.; Gebert, L.; Kleinschmidt, M.C.; Wald, A.; Gläser, S.; Kruse, J.M.; Zickler, D.; Peric, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 T Cell Response in Severe and Fatal COVID-19 in Primary Antibody Deficiency Patients Without Specific Humoral Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 840126. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M.G.; Bruden, D.; Hurlburt, D.; Zanis, C.; Thompson, G.; Rea, L.; Toomey, M.; Townshend-Bulson, L.; Rudolph, K.; Bulkow, L.; et al. Antibody Levels and Protection After Hepatitis B Vaccine: Results of a 30-Year Follow-up Study and Response to a Booster Dose. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, 16–22. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; Peng, Y.; Liang, Y.; Wei, J.; Xing, L.; Guo, L.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Longitudinal analysis of antibody dynamics in COVID-19 convalescents reveals neutralizing responses up to 16 months after infection. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 423–433. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, K.; Li, C.; Zhou, L.; Kong, X.; Peng, J.; Zhu, F.; Bao, C.; Jin, H.; Gao, Q.; et al. Long-Term Kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies and Impact of Inactivated Vaccine on SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies Based on a COVID-19 Patients Cohort. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 829665. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chansaenroj, J.; Yorsaeng, R.; Puenpa, J.; Wanlapakorn, N.; Chirathaworn, C.; Sudhinaraset, N.; Sripramote, M.; Chalongviriyalert, P.; Jirajariyavej, S.; Kiatpanabhikul, P.; et al. Long-term persistence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike protein-specific and neutralizing antibodies in recovered COVID-19 patients. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267102. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebinger, J.E.; Joung, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Weber, B.; Claggett, B.; Botting, P.G.; Sun, N.; Driver, M.; Kao, Y.H.; et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with variations in antibody response to BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination among healthcare workers at an academic medical centre: A longitudinal cohort analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e059994. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P.B.; Donis, R.O.; Koup, R.A.; Fong, Y.; Plotkin, S.A.; Follmann, D. A Covid-19 Milestone Attained—A Correlate of Protection for Vaccines. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 2203–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekliz, M.; Adea, K.; Vetter, P.; Eberhardt, C.S.; Hosszu-Fellous, K.; Vu, D.L.; Puhach, O.; Essaidi-Laziosi, M.; Waldvogel-Abramowski, S.; Stephan, C.; et al. Neutralization capacity of antibodies elicited through homologous or heterologous infection or vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 VOCs. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3840. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO/BS.2020.2403 Establishment of the WHO International Standard and Reference Panel for Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibody. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/WHO-BS-2020.2403 (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Knezevic, I.; Mattiuzzo, G.; Page, M.; Minor, P.; Griffiths, E.; Nuebling, M.; Moorthy, V. WHO International Standard for evaluation of the antibody response to COVID-19 vaccines: Call for urgent action by the scientific community. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e235–e240. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristiansen, P.A.; Page, M.; Bernasconi, V.; Mattiuzzo, G.; Dull, P.; Makar, K.; Plotkin, S.; Knezevic, I. WHO International Standard for anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin. Lancet 2021, 397, 1347–1348. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblatt, D.; Alter, G.; Crotty, S.; Plotkin, S.A. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease. Immunol. Rev. 2022, 310, 6–26. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunau, B.; Prusinkiewicz, M.; Asamoah-Boaheng, M.; Golding, L.; Lavoie, P.M.; Petric, M.; Levett, P.N.; Haig, S.; Barakauskas, V.; Karim, M.E.; et al. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Neutralizing Antibody Titers with Anti-Spike Antibodies and ACE-2 Inhibition among Vaccinated Individuals. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0131522. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblatt, D.; Fiore-Gartland, A.; Johnson, M.; Hunt, A.; Bengt, C.; Zavadska, D.; Snipe, H.D.; Brown, J.S.; Workman, L.; Zar, H.J.; et al. Towards a population-based threshold of protection for COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine 2022, 40, 306–315. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. FDA Takes Action on Updated mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines to Better Protect against Currently Circulating Variants; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, K.E.; Caliendo, A.M.; Arias, C.A.; Englund, J.A.; Hayden, M.K.; Lee, M.J.; Loeb, M.; Patel, R.; Altayar, O.; El Alayli, A.; et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Diagnosis of COVID-19:Serologic Testing. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020. ahead of print. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevadiya, B.D.; Machhi, J.; Herskovitz, J.; Oleynikov, M.D.; Blomberg, W.R.; Bajwa, N.; Soni, D.; Das, S.; Hasan, M.; Patel, M.; et al. Diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacqueline, A.; O’Shaughnessy, P.D. Convalescent Plasma EUA Letter of Authorization; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, L.M. (A Little) Clarity on Convalescent Plasma for Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 666–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korley, F.K.; Durkalski-Mauldin, V.; Yeatts, S.D.; Schulman, K.; Davenport, R.D.; Dumont, L.J.; El Kassar, N.; Foster, L.D.; Hah, J.M.; Jaiswal, S.; et al. Early Convalescent Plasma for High-Risk Outpatients with Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1951–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takashita, E.; Kinoshita, N.; Yamayoshi, S.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Fujisaki, S.; Ito, M.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Chiba, S.; Halfmann, P.; Nagai, H.; et al. Efficacy of Antibodies and Antiviral Drugs against Covid-19 Omicron Variant. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 995–998. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashita, E.; Kinoshita, N.; Yamayoshi, S.; Sakai-Tagawa, Y.; Fujisaki, S.; Ito, M.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Halfmann, P.; Watanabe, S.; Maeda, K.; et al. Efficacy of Antiviral Agents against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariant BA. 2. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1475–1477. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGrace, M.M.; Ghedin, E.; Frieman, M.B.; Krammer, F.; Grifoni, A.; Alisoltani, A.; Alter, G.; Amara, R.R.; Baric, R.S.; Barouch, D.H.; et al. Defining the risk of SARS-CoV-2 variants on immune protection. Nature 2022, 605, 640–652. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.J.; Fish, M.; Jennings, A.; Doores, K.J.; Wellman, P.; Seow, J.; Acors, S.; Graham, C.; Timms, E.; Kenny, J.; et al. Peripheral immunophenotypes in children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1701–1707. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.Y.; Day-Lewis, M.; Henderson, L.A.; Friedman, K.G.; Lo, J.; Roberts, J.E.; Lo, M.S.; Platt, C.D.; Chou, J.; Hoyt, K.J.; et al. Distinct clinical and immunological features of SARS-CoV-2-induced multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130, 5942–5950. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) Interim Guidance, AAP. Available online: https://www.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-mis-c-interim-guidance/ (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Wei, J.; Stoesser, N.; Matthews, P.C.; Ayoubkhani, D.; Studley, R.; Bell, I.; Bell, J.I.; Newton, J.N.; Farrar, J.; Diamond, I.; et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in 45,965 adults from the general population of the United Kingdom. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 1140–1149. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepak, P.; Kim, W.; Paley, M.A.; Yang, M.; Carvidi, A.B.; Demissie, E.G.; El-Qunni, A.A.; Haile, A.; Huang, K.; Kinnett, B.; et al. Effect of Immunosuppression on the Immunogenicity of mRNA Vaccines to SARS-CoV-2: A Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 1572–1585. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendecki, M.; Clarke, C.; Edwards, H.; McIntyre, S.; Mortimer, P.; Gleeson, S.; Martin, P.; Thomson, T.; Randell, P.; Shah, A.; et al. Humoral and T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients receiving immunosuppression. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 1322–1329. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, L.; Laing, A.G.; Muñoz-Ruiz, M.; McKenzie, D.R.; Del Molino Del Barrio, I.; Alaguthurai, T.; Domingo-Vila, C.; Hayday, T.S.; Graham, C.; Seow, J.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: Interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 765–778. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinaki, S.; Adamopoulos, S.; Degiannis, D.; Roussos, S.; Pavlopoulou, I.D.; Hatzakis, A.; Boletis, I.N. Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 2913–2915. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamar, N.; Abravanel, F.; Marion, O.; Romieu-Mourez, R.; Couat, C.; Del Bello, A.; Izopet, J. Assessment of 4 Doses of SARS-CoV-2 Messenger RNA-Based Vaccine in Recipients of a Solid Organ Transplant. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2136030. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfizer and BioNTech Announce Omicron-Adapted COVID-19 Vaccine Candidates Demonstrate High Immune Response Against Omicron. Available online: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-and-biontech-announce-omicron-adapted-covid-19 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Moderna Announces Bivalent Booster Mrna-1273.214 Demonstrates Potent Neutralizing Antibody Response Against Omicron Subvariants Ba.4 And Ba.5. Available online: https://investors.modernatx.com/news/news-details/2022/Moderna-Announces-Bivalent-Booster-mRNA-1273.214-Demonstrates-Potent-Neutralizing-Antibody-Response-Against-Omicron-Subvariants-BA.4-And-BA.5/default.aspx (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- UNDP. Available online: https://data.undp.org/vaccine-equity/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Jacobs, E.T.; Cordova-Marks, F.M.; Farland, L.V.; Ernst, K.C.; Andrews, J.G.; Vu, S.; Heslin, K.M.; Catalfamo, C.; Chen, Z.; Pogreba-Brown, K. Understanding low COVID-19 booster uptake among US adults. Vaccine 2023. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Wyka, K.; White, T.M.; Picchio, C.A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Kamarulzaman, A.; El-Mohandes, A. A survey of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance across 23 countries in 2022. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 366–375. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallano, A.; Ascione, A.; Flego, M. Antibody Response against SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Implications for Diagnosis, Treatment and Vaccine Development. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 41, 393–413. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkhipova-Jenkins, I.; Helfand, M.; Armstrong, C.; Gean, E.; Anderson, J.; Paynter, R.A.; Mackey, K. Antibody Response After SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Implications for Immunity: A Rapid Living Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 811–821. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. In Vitro Diagnostics EUAs—Serology and Other Adaptive Immune Response Tests for SARS-CoV-2. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19-emergency-use-authorizations-medical-devices/in-vitro-diagnostics-euas-serology-and-other-adaptive-immune-response-tests-sars-cov-2 (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Hachmann, N.P.; Miller, J.; Collier, A.Y.; Ventura, J.D.; Yu, J.; Rowe, M.; Bondzie, E.A.; Powers, O.; Surve, N.; Hall, K.; et al. Neutralization Escape by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 86–88. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche Diagnostics. Detecting Coronavirus Variants with Roche Assays. Available online: https://diagnostics.roche.com/us/en/article-listing/assays-detect-coronavirus-variants.html (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Predicted Impact of Variants on Abbott’s SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Diagnostic Tests Abbott. Available online: https://www.molecular.abbott/sal/AMD.15594%20Cross%20Division%20COVID%20Variant%20Tech%20Brief_Web.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- McMahan, K.; Yu, J.; Mercado, N.B.; Loos, C.; Tostanoski, L.H.; Chandrashekar, A.; Liu, J.; Peter, L.; Atyeo, C.; Zhu, A.; et al. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature 2021, 590, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, R.; Narean, J.S.; Wang, L.; Fenn, J.; Pillay, T.; Fernandez, N.D.; Conibear, E.; Koycheva, A.; Davies, M.; Tolosa-Wright, M.; et al. Cross-reactive memory T cells associate with protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in COVID-19 contacts. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, P. The T cell immune response against SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 186–193. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, M.; Torre, D.; Lozano-Ojalvo, D.; Tan, A.T.; Tabaglio, T.; Mzoughi, S.; Sanchez-Tarjuelo, R.; Le Bert, N.; Lim, J.M.E.; Hatem, S.; et al. Rapid, scalable assessment of SARS-CoV-2 cellular immunity by whole-blood PCR. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1680–1689. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.R.; Apostolidis, S.A.; Painter, M.M.; Mathew, D.; Pattekar, A.; Kuthuru, O.; Gouma, S.; Hicks, P.; Meng, W.; Rosenfeld, A.M.; et al. Distinct antibody and memory B cell responses in SARS-CoV-2 naïve and recovered individuals following mRNA vaccination. Sci. Immunol. 2021, 6, eabi6950. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muecksch, F.; Wang, Z.; Cho, A.; Gaebler, C.; Ben Tanfous, T.; DaSilva, J.; Bednarski, E.; Ramos, V.; Zong, S.; Johnson, B.; et al. Increased memory B cell potency and breadth after a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA boost. Nature 2022, 607, 128–134. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, J.M.; Mateus, J.; Kato, Y.; Hastie, K.M.; Yu, E.D.; Faliti, C.E.; Grifoni, A.; Ramirez, S.I.; Haupt, S.; Frazier, A.; et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 2021, 371, eabf4063. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibody Assay (Source) | N (Received Vaccine) | Antibody Level or Titer | Study | Vaccine | Doses | Percent Efficacy | Clinical Endpoint Measure | Days Post Second Dose | Dominant Variant at Time of Study | Population Studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-spike IgG (MSD Diagnostics) | 1051 | 1890 BAU/mL † GMC Ω (95% CI: 1499 to 2465) | COVE [22] | mRNA-1273 (Moderna) | 2 | 90% | Symptomatic COVID-19 | Median 28 | Alpha | General; 47% female, 34% > 65 y/o, 40% at high risk for severe COVID-19, 54% non-white. Infection naive at baseline |

| Anti-S1RBD IgG (MSD Diagnostics) | 2744 BAU/mL † GMC Ω (95% CI: 2056 to 3664) | |||||||||

| Pseudovirus Neutralization assay | 160 IU50/mL ∞ GMC Ω [95% CI: 170 to 220] | |||||||||

| Anti-spike IgG (MSD Diagnostics) | 1155 | 264 BAU/mL † GMC Ω (95% CI: 108 to 806) | COV002 [23] | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) | 2 | 80% | Primary symptomatic COVID-19 | 28 | Alpha | General; 57.9% female, 74.1% < 55 y/o, 24.9% at high risk for severe COVID-19, 92.3% white. Infection naive at baseline |

| Anti-S1RBD IgG (MSD Diagnostics) | 1155 | 506 BAU/mL † Median (95% CI: 135 to NC ‡ [beyond data range]) | ||||||||

| Pseudovirus Neutralization antibodies | 828 | 26 IU50/mL GMC Ω (95% CI: NC ‡ to NC ‡) | ||||||||

| Live-Virus Neutralization antibodies | 412 | 247 normalized neutralization titer (NF50) (95% CI: 101 to NC ‡) | ||||||||

| Anti-spike IgG (MSD Diagnostics) | 826 | 238 BAU/mL 97.5th percentile | ENSEMBLE [25] | Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen) | 1 | 89% | Moderate to severe-critical COVID-19 | 29 | Alpha | General; 44.8% female, 50.4% ≥ 60 y/o, 51.7% at high risk for severe COVID-19, 49.3% non-white. Infection naive at baseline |

| Anti-S1RBD IgG (MSD Diagnostics) | 173 BAU/mL 97.5th percentile | |||||||||

| Pseudovirus Neutralization Assay | 96.3 IU50/mL ∞ 97.5th percentile | |||||||||

| Anti-spike IgG (MSD Diagnostics) Anti-S1RBD IgG (MSD Diagnostics) | 19,996 | 1552 BAU/mL † GMC Ω (95% CI: 1407 to 1713) 2123 BAU/mL † GMC Ω (95% CI: 1904 to 2369) | PREVENT-19 [24,26,27] | NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) | 2 | 87.7% | Symptomatic COVID-19 | 35 | Primarily Alpha | General; 46.7% female, 46.7% ≥ 65 y/o, 49.7% at high risk for severe COVID-19, 42.5% non-white. Infection naive at baseline |

| Pseudovirus Neutralization Assay | 461 IU50/mL ∞ GMC Ω (95% CI: 404 to 526) | |||||||||

| Anti-S1RBD IgG (Abbott Diagnostics) | 52 | 2018.0 BAU/mL † Median | Deeba et al., 2022 [28] | BNT162b2 (Pfizer) | 2 | N/A | N/A | ~21 | Omicron (BA.2) | Healthcare professionals in Cypress |

| 45 | 182.1 BAU/mL Median | ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) | 2 | |||||||

| Anti-S1RBD IgG (In-house ELISA) | 86 | 1209 BAU/mL † Mean (in previously infected) or >694 BAU/mL † (correlated to excellent neutralizing activity) | Claro et al., 2022 [29] | Sputnik | 2 | 91% in infection naive; 100% in previously infected | Good to excellent neutralizing activity as defined by WHO standardized neutralizing antibody response of 100–400 or greater IU/mL | 42 | Alpha (B.1.17) | Healthcare professionals in Venezuela |

| Anti-S1RBD IgG (Abbott Diagnostics) | 1343 | 1432 BAU/mL

† Median | Bordi et al., 2022 [30] | BNT162b2 (Pfizer) | 2 | N/A | N/A | ~30 | Delta | Healthcare professionals in Italy |

| Anti-S1RBD IgG (Snibe Co., MAGLUMI) | 2248 | 1372 BAU/mL

† Median | Lo Sasso et al., 2021 [31] | BNT162b2 (Pfizer) | 2 | N/A | N/A | 10–20 | Mainly Alpha | Outpatients presenting for blood draw in Italy |

| Anti-S1 IgG (Euroimmun Anti-SARS-CoV-2-QuantiVac-ELISA) | 93 (age < 60 y/o) | 3702 BAU/mL

† Mean | Muller et al., 2021 [32] | BNT162b2 (Pfizer) | 2 | 17 | Mainly Alpha | Infection naive adults (younger and older elderly populations) from nursing home facilities in Germany | ||

| 83 (age > 80 y/o) | 1332 BAU/mL † Mean | |||||||||

| In-house PRNT (neutralization) assay | 93 (age < 60 y/o) | ID50 ∗: 97.8% | ||||||||

| 83 (age > 80 y/o) | ID50 ∗: 68.7% | |||||||||

| Anti-S1 IgG (Euroimmun Anti-SARS-CoV-2-QuantiVac-ELISA) | 107 out of 263 | 2478 BAU/mL † Mean (before Omicron BA.1/2 breakthrough) | Kajanova et al., 2023 [33] | Several vaccines | At least 2 (or series completed) | No breakthrough infection during period studied | N/A | Omicron BA.1/2 | Healthy adult volunteers; 76% female, 24% male; median age 45 y/o, in Slovakia with previous vaccination series completed | |

| 152 out of 263 | 3803 BAU/mL

† Mean (before NO Omicron BA.1/2 breakthrough) | 100% | ||||||||

| 141 out of 263 | >6201.5 BAU/mL † (upper most quartile of responses most likely to avoid breakthrough infection) |

| Clinical Use Cases | |

|---|---|

| Late Diagnosis | Patients presenting 3–4 weeks after symptom onset with negative viral testing can have recent exposure/infection confirmed with appropriate antibody testing (e.g., IgG S and IgG N). |

| Convalescent Plasma (CP) | Screening CP donors for appropriately high levels of antibodies prior to donation. |

| Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) | Many children with MIS-C following infection will have detectable antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 but a negative NAAT test. |

| Correlates of protection (CoPs) | A conservatively high antibody response, ideally standardized to WHO or other acceptable standardization (i.e., reportable in BAU/mL) for IgG or total antibody to S1-RBD could be proposed based on correlation to neutralizing antibody assay(s) or based on vaccine response achieved in immunocompetent populations. Further the endpoint for protection needs to be agreed upon (e.g., protection from severe disease requiring hospitalization). |

| Post-acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) | It may be useful to follow antibody levels pre- and post-vaccination in these patients to understand their individual responses, including neutralizing antibody development. |

| Booster vaccine dosing | Antibody response can be used as a general determinant for booster dose necessity where vaccine availability is limited (e.g., in the developing world) or a patient’s desire to not be exposed to additional, potentially unnecessary doses (e.g., those who have experienced non-life-threatening side effects). |

| Limitations | |

| Negative results in the acute stage post-infection or post-vaccine | Need to wait at least 14 days post-symptomatic infection to assess antibody levels. To assess peak antibody response, waiting 3–4 weeks post-vaccine dose or post-infection is suggested. |

| False positives | Despite low sequence identity (i.e., ~30%) for S protein between SARS-CoV-2 and other alpha and beta coronaviruses (excluding SARS-CoV-1), positive antibody reactions from recent exposure to other coronaviruses (e.g., OC43 and HKU1) may occur. |

| Binding antibody correlates of protection (CoPs) | An agreed-upon conservative CoP threshold or range remains to be confirmed by guideline-forming bodies and will likely need to be updated over time. A conservative range of peak IgG S1-RBD responses (i.e., 1372–2744 BAU/mL) applicable to the first-generation mRNA and recombinant protein vaccines was extracted from several studies (see Section 2). |

| Waning of antibodies | It has been noted by many studies that antibody levels wane over time. The timing for a booster dose has been suggested by the CDC based on age, immunocompromised status, and type of vaccine administered. At the low end, a period of ~3–6 months for boosting may be suggested for the immunocompromised or elderly. Additionally, a peak antibody response may be expected at the 3–4 week timeframe for most individuals and is the suggested ideal time to measure antibody response. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sobhani, K.; Cheng, S.; Binder, R.A.; Mantis, N.J.; Crawford, J.M.; Okoye, N.; Braun, J.G.; Joung, S.; Wang, M.; Lozanski, G.; et al. Clinical Utility of SARS-CoV-2 Serological Testing and Defining a Correlate of Protection. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11111644

Sobhani K, Cheng S, Binder RA, Mantis NJ, Crawford JM, Okoye N, Braun JG, Joung S, Wang M, Lozanski G, et al. Clinical Utility of SARS-CoV-2 Serological Testing and Defining a Correlate of Protection. Vaccines. 2023; 11(11):1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11111644

Chicago/Turabian StyleSobhani, Kimia, Susan Cheng, Raquel A. Binder, Nicholas J. Mantis, James M. Crawford, Nkemakonam Okoye, Jonathan G. Braun, Sandy Joung, Minhao Wang, Gerard Lozanski, and et al. 2023. "Clinical Utility of SARS-CoV-2 Serological Testing and Defining a Correlate of Protection" Vaccines 11, no. 11: 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11111644

APA StyleSobhani, K., Cheng, S., Binder, R. A., Mantis, N. J., Crawford, J. M., Okoye, N., Braun, J. G., Joung, S., Wang, M., Lozanski, G., King, C. L., Roback, J. D., Granger, D. A., Boppana, S. B., & Karger, A. B. (2023). Clinical Utility of SARS-CoV-2 Serological Testing and Defining a Correlate of Protection. Vaccines, 11(11), 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11111644