Abstract

COVID-19 vaccines have met varying levels of acceptance and hesitancy in different parts of the world, which has implications for eliminating the COVID-19 pandemic. The aim of this systematic review is to examine how and why the rates of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy differ across countries and continents. PubMed, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore and Science Direct were searched between 1 January 2020 and 31 July 2021 using keywords such as “COVID-19 vaccine acceptance”. 81 peer-reviewed publications were found to be eligible for review. The analysis shows that there are global variations in vaccine acceptance among different populations. The vaccine-acceptance rates were the highest amongst adults in Ecuador (97%), Malaysia (94.3%) and Indonesia (93.3%) and the lowest amongst adults in Lebanon (21.0%). The general healthcare workers (HCWs) in China (86.20%) and nurses in Italy (91.50%) had the highest acceptance rates, whereas HCWs in the Democratic Republic of Congo had the lowest acceptance (27.70%). A nonparametric one-way ANOVA showed that the differences in vaccine-acceptance rates were statistically significant (H (49) = 75.302, p = 0.009*) between the analyzed countries. However, the reasons behind vaccine hesitancy and acceptance were similar across the board. Low vaccine acceptance was associated with low levels of education and awareness, and inefficient government efforts and initiatives. Furthermore, poor influenza-vaccination history, as well as conspiracy theories relating to infertility and misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine on social media also resulted in vaccine hesitancy. Strategies to address these concerns may increase global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and accelerate our efforts to eliminate this pandemic.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted many aspects of our everyday lives and changed the socio-economic fabric of the entire world [1,2,3,4]. The COVID-19 disease is caused by the highly contagious severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and, at the time of its outbreak, no vaccine was available to prevent individuals from contracting the infection. Therefore, countries had to take stringent measures in order to contain the infection, including nation-wide lockdowns and border closures [5,6,7,8]. Along with countries implementing lockdowns, home-healthcare services were also optimized in order to cater to the needs of COVID-19 patients at their homes in case they either did not require hospitalization or could not be admitted to hospitals due to a lack of patient beds or other vital medical facilities [9,10]. Multi-objective home-healthcare services involving the use of artificial-intelligence models were introduced, ensuring patient availability and convenience [9]. Furthermore, home-healthcare supply-chain frameworks have also been introduced based on programming models that aid patients in selecting pharmacies, enhance the selection and routing of nurses and also help caregivers connect with patients in a timely manner [10]. Despite these protective measures, the coronavirus continued to spread and harm individuals including children, the elderly and people with medical conditions such as cancer, diabetes and respiratory diseases, who were also at the highest risk of contracting the infection [5,11,12,13]. Individuals who required access to routine medical services such as pregnant women and people with chronic conditions experienced mental health issues such as stress, depression and reduced emotional well-being [14,15,16,17]. The emotional well-being of parents and children also suffered due to the lack of educational and food resources and the enhanced stress and financial problems due to restricted and insufficient healthcare facilities, especially in less-developed countries [18,19,20,21,22]. Due to the overwhelming number of positive cases and the limited availability of medical devices, the pressure on healthcare workers (HCWs) has significantly increased and placed them at higher risk of contracting the contagion. Several studies have reported clinically significant depression, stress and decreased mental well-being in HCWs [23,24]. Due to these numerous harmful effects of the COVID-19 virus, there is a crucial need to develop and administer vaccines in order to eliminate this deadly pandemic [24,25].

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) has been cooperating with the World Health Organization (WHO) to aid the vaccine developers in successfully developing and deploying COVID-19 vaccines [26]. The rapid development of the COVID-19 vaccine was seen as a necessity to suppress the repeated infection waves and lower the mortality rate [27]. The COVID-19 vaccine-development efforts started in March 2020 with the first vaccine candidate entering human trials on 16 March 2020. On 4 January 2021, the United Kingdom (U.K.) became the first country to administer a COVID-19 vaccine, which was manufactured by AstraZeneca in association with Oxford University [28]. Soon, other countries started their own vaccine campaigns. For example, China administered vaccines developed by home manufacturers such as Sinopharm, Sinovac and Cansino Biologica; Russia administered its vaccine known as Sputnik V; and the United States (U.S.) has been using vaccines developed by home manufacturers including Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna, and Johnson and Johnson [28]. The rapid and sustained administration of the COVID-19 vaccine is critical for the world to return to the pre-pandemic normalcy. As of November 2021, one hundred and seventy-five vaccines are in clinical trials, forty-one have been approved and reached the final testing phase, and seventy-five are undergoing animal trials. Although the current progress in vaccine development and administration is encouraging, social-distancing and face-mask mandates are still in place in various regions to counteract the infection [29,30,31]. This is because, to be effective, the COVID-19 vaccines must be administered to the majority of the world population [32]. However, variations in vaccine acceptance and hesitancy have been observed in different groups across the world [33]. This means that the world, at large, is at risk of yet another pandemic as new SARS-CoV-2 variants continue to emerge.

At this time, there is a need to understand how and why COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance and hesitancy rates differ in various parts of the world, so institutions such as governments and non-governmental organizations can formulate strategies to promote COVID-19 vaccines in their respective regions. To this end, researchers have been studying COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in specific regions of the world [34,35]. A few systematic reviews analyzing the worldwide vaccine-hesitancy and acceptance rates have also recently surfaced [36,37]. However, there has not been a systematic and comparative study of the variations in vaccine acceptance across countries. In addition, a study of the social and behavioral factors responsible for the significant differences in acceptance rates is needed in order to understand the reasons behind acceptance and hesitancy of the COVID-19 vaccine in different world regions. A systematic review that statistically analyzes the differences in COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates of different countries, along with the reasons behind these rates, can support such an endeavor. It can also aid in the identification of fundamental social and behavioral factors that are ultimately responsible for vaccine acceptance and hesitancy. Researchers can use such results to conduct additional research to understand the correlations between COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and other factors in different contexts. Furthermore, government agencies and non-governmental organizations can use this knowledge to devise strategies to accelerate vaccine acceptance all over the world and put an end to this pandemic. In essence, our research questions are as follows:

- How do the COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates differ among different countries?

- How do the COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates differ among different continents?

- What social and behavioral factors are responsible for country-level differences in COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates?

In accordance with the research questions, the following are the highlights of our research:

- A systematic and comparative study about the variations in COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates across different countries and continents.

- Statistical analysis of the reported COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates.

- Determination of associated social and behavioral factors in relation to COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and vaccine hesitancy.

2. Materials and Methods

We report this systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [38] as well as the essential statement recommendations [38]. This section comprises the information sources and the search strategies that were employed for obtaining the selected studies. This is followed by the study-selection process and the eligibility criteria including the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The section is concluded with a statistical analysis that was executed to determine if there is a significant difference between the reported vaccine-acceptance rates of different countries.

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

Relevant publications were identified through electronic searches in four databases: PubMed, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore and Science Direct. Articles were screened within the time period from 1 January 2020 to 31 July 2021. The databases were searched using the following keywords: “COVID-19”, “vaccine acceptance”, “vaccine hesitancy”, and “associated factors”. The Boolean operator ‘AND’ was utilized for searching the databases with the mentioned keywords.

2.2. Study Selection

The authors first screened article titles and abstracts to remove all the duplicates. The remaining articles were then independently reviewed, which involved reading article titles, abstracts and methods. The articles that did not meet our inclusion criteria, which were summarized as PVAF (Peer-reviewed (P), about the COVID-19 vaccine (V), reports the acceptance rate (A), provides social and/or behavioral factors (F)), were removed. The authors then met to compare their article selections and resolve disagreements through productive discussions. Once the article selection was finalized, the full text of each was independently reviewed by the authors.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Peer-reviewed publications that reported COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and the associated social and behavioral factors responsible for vaccine hesitancy were considered for inclusion. Furthermore, only studies published in English met the eligibility criteria. The exclusion criteria excluded articles that were pre-prints or unpublished as well as articles in a language other than English.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A nonparametric one-way ANOVA was performed using the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 26.0 on a Windows 10 machine to investigate whether a statistically significant difference existed between the reported vaccine-acceptance rates of different countries. This was followed by the application of the Kruskal–Wallis H test to conduct pairwise comparisons between the vaccine-acceptance rates of all the included countries.

3. Results

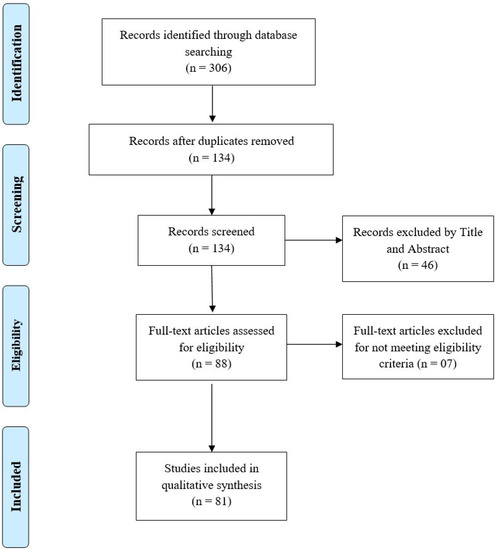

The initial electronic search strategy returned 306 research articles, as demonstrated by Figure 1. Only peer-reviewed research articles published in journals were taken into consideration. After the removal of the duplicates, 134 research articles remained; of these, 46 publications were excluded after title and abstract reviews because they did not report COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance and hesitancy rates, and/or the associated social and behavioral factors. The remaining 88 articles then underwent elaborate reviews in which each section of every research article was thoroughly analyzed. Following this, 81 relevant research articles were selected for inclusion in this systematic review. Table 1 summarizes the selected research articles along with their publication year, number and type of participants, COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates, and acceptance and hesitancy factors.

Figure 1.

Study identification PRISMA flowchart.

Table 1.

Summary of the studies included in the systematic review based on the vaccine-acceptance rates and their associated social and behavioral factors. AF: acceptance factors; HF: hesitancy factors; HCWs: healthcare workers.

3.1. Characteristics of the Papers Included

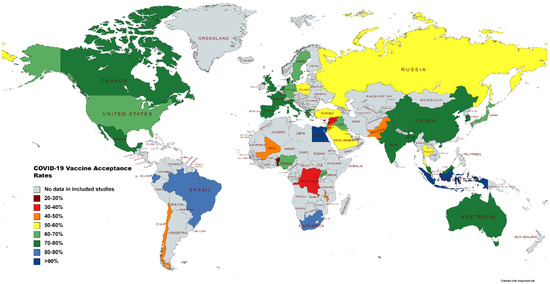

81 papers were selected for this systematic review, with the most papers being from China (n = 12), followed by Italy (n = 8) and then the U.S (n = 8). Also included in this review were studies conducted in Saudi Arabia (n = 5), France (n = 4), Hong Kong (n = 4), Turkey (n = 4) and the U.K. (n = 4). While the majority of the studies were published in 2020, the most recent paper was published in June 2021. Six studies involved more than one country. Neumann-Böhme et al. [95] published a study spanning seven European countries, Lazarus et al. [34] focused on nineteen countries, and the research of Bono et al. [35] was conducted in nine countries. Taylor et al. [110], Salali and Uysal [98] and Sallam et al. [55] conducted their studies in two countries each. All of the studies focused on adults, with the exception of Zhang et al. [74], who worked with children below 18 years of age. Among the included studies, 57 surveys included the general population and 16 included HCWs. Three studies focused on multiple groups including the general population, HCWs and healthcare college students [68,78,88]. Two studies focused solely on dentists, dental surgeons and dental students [104]. Lazarus et al. [34] had the largest sample size (n = 13,426), while Mascarenhas et al. [104] had the smallest (n = 248). A total of fifty countries that reported their COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates are highlighted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Map illustrating vaccine-acceptance rates worldwide.

3.2. Rates of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance

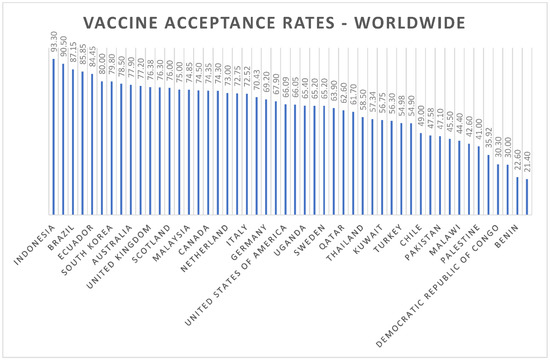

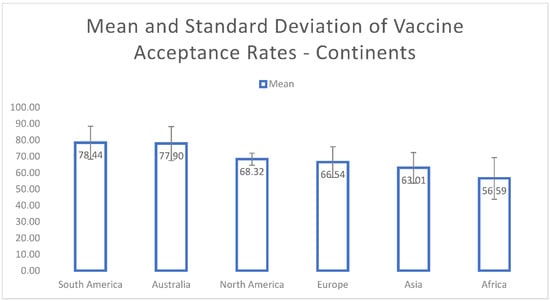

The mean COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates of countries are illustrated in Figure 3. Indonesia (93.30%) had the highest mean vaccine-acceptance rate followed by Egypt (90.50%), Brazil (87.15%), South Africa (85.85%), Ecuador (84.45%) and Denmark (80%). The means and standard deviations for the continents are shown in Figure 4. We found that the highest mean vaccine-acceptance rate was reported by South America (78.44%), whereas the lowest mean vaccine-acceptance rate was reported in Africa (56.59%).

Figure 3.

Worldwide COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates.

Figure 4.

Mean and standard deviation of COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates for continents.

Among adults from the general population, the highest vaccine-acceptance rates were reported in Ecuador (97%), Malaysia (94.3%) and Indonesia (93.3%), and the lowest rate was reported in Lebanon (21.40%). In the healthcare workers (HCWs) category, general HCWs in China (86.20%) and nurses in Italy (91.50%) had the highest acceptance rates. The HCWs in the Democratic Republic of Congo had the lowest acceptance rate (27.70%). Among the patients with chronic diseases, those with rheumatic disease in Turkey showed a vaccine-acceptance rate of 29.2%, adolescent cancer survivors in the U.S. had an acceptance rate of 63%, and patients with type-two diabetes mellitus in Italy reported an acceptance rate of 85.80%. One study based in China reported a 77.4% vaccine-acceptance rate among pregnant women.

3.3. Demographic Factors Influencing COVID-19 Vaccine-Acceptance Rates

3.3.1. North America

The mean COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates in the North American countries, particularly the United States (U.S.), Mexico and Canada, were in the range of 56% and 75%. The general-population participants who were recruited in the U.S., Canada and Mexico by Lazarus et al. [34] exhibited COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates of 76.3%, 75.4% and 68.7% respectively. Social influences, including an employer’s advice to get vaccinated, and behavioral factors, such as an accelerated trust in government directives about the significance of getting vaccinated against COVID-19, played a major role in achieving enhanced vaccine-acceptance rates.

Lower vaccine-acceptance rates were found in studies by Mascarenhas et al. [104] and Viswaanth et al. [105], where 56% and 65% individuals in the United States, respectively, were found to be willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. The lowered trust in public-health experts and the perceived risk of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine were the major behavioral factors responsible for low vaccine-acceptance rates among dental students in the U.S. [104]. Social factors including a higher exposure to different social-media platforms combined with the behavioral perceptions about the risks of vaccines were the major factors responsible for lower vaccine-acceptance rates in U.S. adults [105]. The educational background was mentioned as the major socio-demographic factor responsible for low vaccine acceptance (63%) among adolescent and young-adult cancer survivors in the U.S. [103]. The behavioral determinants pertaining to the hesitancy towards the COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S. and Canada comprised of misconceptions and misinformation surrounding the efficacy and side effects of the vaccine [106,107]. Testing time and the requirement of a second dose also led to decreased acceptance rates [107].

Overall, social dynamics in the United States including low educational levels and awareness, race, younger age, gender, employment directives and lack of trust in government institutions led to lowered vaccine-acceptance rates [106,108,109]. Furthermore, in the U.S. and Canada, many individuals mentioned relying upon their natural immunity instead of receiving the vaccine [110].

3.3.2. South America

The COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rate in South America ranged from 49% to 97%. The lowest vaccine-acceptance rate was found in Chile where 49% of the participants were willing to receive a vaccine [116]. The low vaccine-acceptance rate in Chile was due to the lack of government-initiated vaccine-awareness campaigns and the perceived vaccine side effects among the general public [116].

On the contrary, the highest vaccine-acceptance rate was observed in Ecuador where 97% of the surveyed adults were eager to get vaccinated [117]. Ecuador was characterized by an accelerated trust in government institutions and higher vaccine-related education. Furthermore, people showed a willingness to pay for the vaccine [117].

3.3.3. Europe

The vaccine-acceptance rate in Europe ranged from 27% to 91.5%. Neumann-Bohme et al. [95] studied seven European countries, which included Denmark, the U.K., Portugal, the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Italy. Vaccine hesitancy was related to mistrust in a vaccine that had been prepared in a very short amount of time. Eight studies were conducted in Italy, with the lowest vaccine-acceptance rate reported as 27% [80] and the highest as 91.5% [83]. Another study [80] surveyed parents about vaccinating their children and found that the uncertainty about vaccine safety was the major factor for vaccine rejection.

Two studies carried out in Scotland demonstrated a higher vaccine-acceptance rate; the earlier study reported an acceptance rate of 74% and the latter reported 78% [89]. Williams et al. [89] associated socio-demographic factors such as higher income and social status with a higher intention to receive the vaccine. Four separate studies focusing on France determined the vaccine-acceptance rate to range from 71.2% [92] to 77.6% [99]. Gagneux-Brunon et al. [93] analyzed vaccine acceptance among HCWs in France and found that nurses were more hesitant towards getting vaccinated. Detoc et al. [99] assessed the general population in France and related vaccine hesitancy to the perceived risks. Four studies were also carried out in the U.K. and reported vaccine acceptance ranging from 64% [94] to 89.10% [97]. Racial and ethnic minorities and low-income households were most prominently linked with vaccine hesitancy in the U.K. [97]. Turkey had a lower vaccine-acceptance rate ranging from 34.6% [88] to 51.6% [86]. Yigit et al. [87] focused on HCWs in Turkey and İkiışık et al. [86] targeted the general population. Both studies found age to be a factor in vaccine hesitancy; specifically, a younger age was associated with a greater vaccine hesitancy. Only one study from Cyprus was considered in this review, and it showed a very low acceptance rate of 30% [90]. This was mainly due to the fear of side effects related to the vaccine.

Social and behavioral factors such as anxiety, government enforcement and risk perception proved to be hindrances to vaccine acceptance in countries such as the U.K. and Turkey [98]. Vaccine hesitancy was also associated with negative beliefs including mistrust, conspiracy theories and negative support by the health professionals [96]. The female sex and confidence in vaccine efficacy were related to higher vaccine acceptance [83]. Fear of the unknown scientific results led to a very low vaccine-acceptance rate among patients with rheumatic diseases in Turkey [88].

3.3.4. Australia

Two studies carried out in Australia have been considered in this review. Both reported high vaccine-acceptance rates of 75% to 80%. Rhodes et al. [112] studied parents of school-going children (n = 2018). Researchers indicated that knowledge about COVID-19 and older age were key factors in vaccine acceptance. Seale et al. reported that family support greatly increased vaccine acceptance [111].

3.3.5. Asia

The vaccine-acceptance rates for Asia, as reported in the included studies, ranged from 21.40% to 94.30%. China, where the largest number of studies were reported, ranged in acceptance rates from 36.40% to 91.30%. Low vaccine-acceptance rates in China were found to be prevalent among college students and children below 18 years of age. The general population, HCWs and pregnant women exhibited high vaccine-acceptance rates. The factors associated with higher acceptance rates included an enhanced trust in government initiatives, an employer’s advice regarding vaccination, and valuing a health professional’s recommendation due to being at higher risk of infection [39,40,41,46,47,72,73]. The factors associated with lower acceptance rates were a lack of confidence in the effectiveness of the vaccine, its side effects, and a lack of knowledge or misinformation among the participants regarding the potential harms of the vaccines [42,43,74].

Saudi Arabia reported acceptance rates ranging from 48.00% to 64.70%. Socio-demographic factors such as high income, being married, and being a resident of a major city were negatively correlated with vaccine acceptance [77]. On the contrary, factors associated with vaccine acceptance included positive information and awareness regarding the effectiveness of vaccines and the previous uptake of influenza vaccine. Government strategies and initiatives including advertisements about the benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine and targeted health education were used for spreading positive information and awareness regarding the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine [77]. Uncertainty surrounding the safety and efficacy of the vaccines increased vaccine hesitancy among participants [48,49,50,51].

Low vaccine-acceptance rates in Kuwait and Jordan were reported due to behavioral and social factors including low confidence in healthcare professionals, belief in conspiracy theories such as that vaccines lead to infertility, and misinformation such as that the vaccine alters one’s genes, that it contains a tracking device, or that it is unsafe [52,53,54,55,56,57].

The higher acceptance rate in Malaysia was due to socio-economic factors such as higher education levels and self-awareness [79]. In Hong Kong, lower acceptance rates were associated with low education levels, a lack of vaccine-awareness initiatives by the government, and a history of past pandemic sufferings [58,60,75]. The safety of the vaccines was also a major issue and it negatively impacted smokers’ and chronic-disease patients’ decisions to get vaccinated [59].

The higher acceptance rates reported in the rest of the Asian countries were due to self-awareness among participants. Participants of older age groups were more willing to get vaccinated as well as those who trusted their governments, employers and healthcare professionals. The participants who showed hesitancy towards vaccines were more concerned about their side effects than their benefits. This was usually observed in low-income and low-education groups.

3.3.6. Africa

The vaccine-acceptance rates in Africa ranged from 27.70% to 90.50%. The highest vaccine-acceptance rate among African countries was exhibited by South Africa where 90.50% participants were willing to get vaccinated [113]. Socio-demographic factors including higher income and government initiatives, such as campaigns releasing information about the vaccination in a timely manner and public service announcements on cellular networks about getting vaccinated, played a major role in the higher acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines [113]. Other factors associated with vaccine acceptance included positive information and awareness about the benefits of vaccines and the previous uptake of influenza vaccine [34].

The factors associated with higher acceptance rates in other African countries were higher education levels that led to higher awareness and knowledge about the advantages of getting vaccinated, and the government and employers making vaccination mandatory [35]. In countries such as Democratic Republic of Congo, where a low vaccine-acceptance rate of 27.70% was reported, factors such being of a younger age and lacking knowledge about COVID-19 vaccines and their benefits led people to believe that it was unsafe to get vaccinated [115]. Participants with a history of chronic diseases were also linked with vaccine hesitancy.

3.4. Comparisons between Countries

The one-way ANOVA revealed that there was a statistically significant difference in the COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates of at least two countries (H (49) = 75.302, p = 0.009*).

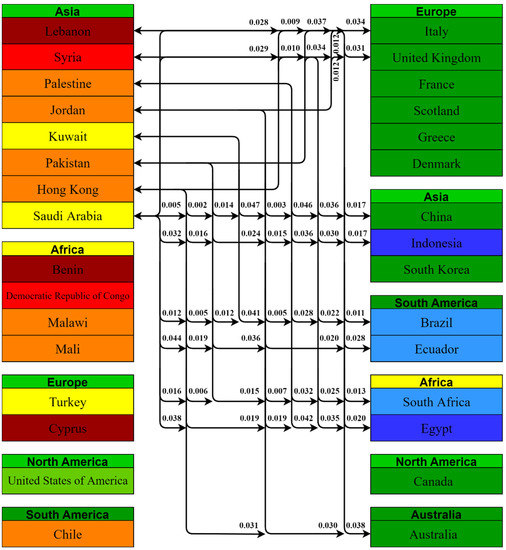

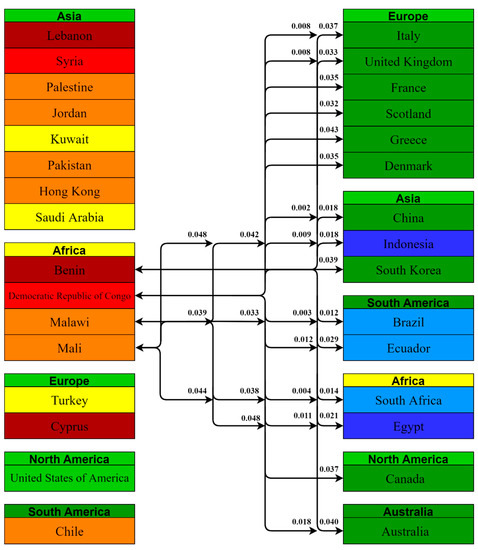

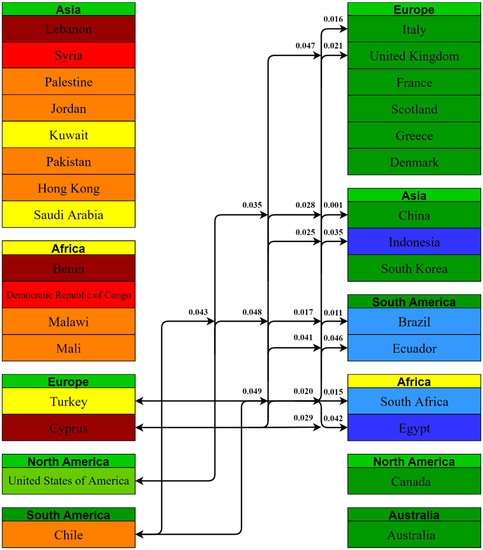

Using the Kruskal–Wallis H Test, a total of 1225 comparisons were obtained between the 50 countries included in this study, among which only 105 comparisons had a value of p < 0.05, i.e., 31 countries had statistically significant differences between some of their vaccine-acceptance rates. We grouped the countries by their continents and the statistically significant p values are presented in Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 5.

Pairwise comparison between Asian countries having lesser acceptance rates with the rest of the world and their p values.

Figure 6.

Pairwise comparison between African countries having lesser acceptance rates with the rest of the world and their p values.

Figure 7.

Pairwise comparison between European, North and South American countries having lesser acceptance rates with the rest of the world and their p values.

Asian countries with lower acceptance rates had 55 statistically significant comparisons; 15 of these comparisons were with other Asian countries, 14 with African countries, 13 with South American countries, 10 with European countries and 3 with Australia. Lebanon, Jordan, and Hong Kong were involved in nine statistically significant (p < 0.05) comparisons.

African countries with lower acceptance rates had statistically significant comparisons with 31 countries; 8 comparisons were with European countries, 7 with other Asian countries, 7 with other African countries, and 6 with South American countries. Democratic Republic of Congo had the most comparisons, i.e., 15, with a value of p < 0.05, which is the highest among the included countries.

European countries with lower acceptance rates had statistically significant comparisons with 15 countries; Asian, South American and African countries each had 4 comparisons whereas 3 comparisons were with European countries.

North and South American countries with comparatively lower acceptance rates had two comparisons each with other countries of the world.

4. Discussion

The willingness to accept a vaccine is known to be triggered by three parameters: complacency, confidence and convenience [33]. Complacency refers to the assumption that the risk of contracting a particular disease is low and hence, that vaccination is inessential and avoidable [36,118]. Confidence is one’s level of trust and conviction in the welfare and usefulness of vaccination. Convenience involves the comfort provided to the population in terms of vaccine accessibility, affordability and supply [36].

With the start of the spread of the coronavirus, the rapid development of vaccines began and ultimately, the deployment of vaccines against COVID-19 was witnessed. However, in order to build herd immunity and ensure that mortality rates are lowered, worldwide vaccine acceptance is necessary [119]. Vaccine hesitancy has been observed to be a major hindrance in the global efforts to curb the spread of the coronavirus and is primarily due to social and behavioral influences [120]. Hence, the goals of this systematic review comprised of assessing the differences in COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates among different countries and among different continents. Furthermore, this systematic review aimed to determine the social and behavioral factors that form the basis for significant differences between COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among different countries and continents. Our findings support the aims of this systematic review and the results demonstrated differences between COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates among different countries. Indonesia reported the highest mean vaccine-acceptance rate (93.30%), whereas Lebanon demonstrated the lowest mean acceptance rate of 21.40%. Similarly, the findings of this systematic review demonstrated the differences between COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates among different continents, with South America exhibiting the highest mean acceptance rate of 78.44%, while Africa reported the lowest rate of 56.59%. Certain social and behavioral factors that differed between different countries and continents were responsible for the significant differences between COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates.

Significant differences were found between the vaccine-acceptance rates of North America and Europe pertaining to the social and behavioral factors. Lower vaccine-acceptance rates were found in Europe, particularly in countries including the U.K and Denmark, due to reasons such as low income, cultural influences, political beliefs and conspiracy theories relating to the negative attitude of medical professionals [95,96,97]. Hence, in order to enhance the vaccine-acceptance rates in Europe, government institutions should implement strategies that help to eliminate political differences and cultural influences. Community groups can also hold seminars that help individuals not to believe in conspiracy theories and persuade them about the potential benefits of receiving the COVID-19 vaccine [121]. Significant differences between vaccine-acceptance rates were also found between North America and Asia. Lower vaccine-acceptance rates in Asia were due to factors including low educational levels, a lack of awareness regarding the potential benefits of vaccination, low levels of income and a lack of confidence among the individuals [39,40,41,42,43]. Concerns regarding virus mutation were also prevalent in Asia [44].

Significant differences were found between the vaccine-acceptance rates in South America and Asia. Lower vaccine-acceptance rates in Asia were due to factors including a lack of adequate knowledge and awareness, low educational levels, an absence of influenza vaccine history and the prevalence of conspiracy theories including perceived risks about vaccination leading to infertility [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,59]. Moreover, a preference for natural immunity and misinformation on social-media platforms also contributed to low vaccine-acceptance rates in Asia [70]. Significant differences between vaccine-acceptance rates were found in Europe and Asia. The low vaccine-acceptance rate in Asia was due to low levels of education and awareness, the prevalence of conspiracy theories relating to infertility and side effects, a poor influenza vaccination history and a lack of confidence in healthcare professionals [60,61,62,63,64]. Moreover, people in Asia preferred their natural immunity over vaccines and social-media influence also played a role in creating misinformation and spreading conspiracy theories among the population [70].

Significant differences were observed between COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates in Australia and Asia. The reasons for low vaccine-acceptance rates in Asia were primarily due to low levels of education and awareness, the prevalence of conspiracy theories relating to infertility and side effects, a poor influenza vaccination history and a lack of confidence in healthcare professionals [65,66,67,68,69,72,73,74,75]. Hence, there is a need for government institutions and non-governmental organizations in Asia to devise and implement campaigns that help to elevate the awareness level relating to the administration of the COVID-19 vaccine. Enhanced awareness levels will also boost the confidence among individuals and the perceived risks associated with virus mutation and vaccine safety will also decrease [122]. Moreover, information-technology companies in Asia should focus on eliminating incorrect information about the COVID-19 vaccine on different social-media platforms and instead should ensure the creation of websites and webpages that indicate the advantages of receiving the vaccine [123].

The findings of this systematic review helped to identify the social and behavioral factors responsible for the significant differences between vaccine-acceptance rates that were observed in South America and Africa. Africa reported lower vaccine-acceptance rates as compared to South America due to individuals having a history of vaccine refusal, including the influenza vaccine [34,35]. A lack of knowledge and adequate awareness regarding the benefits of vaccination also played a major role in the lower vaccine acceptance in Africa [115].

Significant differences in vaccine-acceptance rates were found in Africa and Asia. Africa reported lower COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates primarily due to the major factor of vaccine refusal [34,35]. People in Africa reported a history of poor influenza vaccination due to fewer awareness programs initiated by the government and as a result they also showed resistance towards the COVID-19 vaccine. Moreover, high vaccine refusal was also due to the increased illiteracy rate in Africa as compared to Asia [115]. Similar differences were also found between Europe and Africa. Africa reported low vaccine-acceptance rates due to individuals exhibiting poor influenza vaccination history and a history of vaccine refusal due to low educational levels [34,35]. Hence, government institutions and non-government establishments in Africa should work towards drafting and implementing strategies that will help to gain the trust of individuals and accelerate vaccine acceptance.

5. Conclusions

COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates differ according to the countries and continents of the world. The majority of the studies included in this systematic review reported COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates of >60%. However, the lowest rate of 21.40% was reported by a study analyzing vaccine acceptance in Lebanon. The mean COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rate among continents showed that South America had a greater population willing to become vaccinated against coronavirus. On the contrary, African countries reported significantly lower acceptance rates and hence, Africa has the lowest mean vaccine-acceptance rate.

The high and low COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates stemmed from various social and behavioral characteristics exhibited by the participants in the studies included in this systematic review. High COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates in South America, Australia and Europe emerged due to certain factors such as the increased trust of individuals in government health policies and the efficient strategies formulated by the policy makers, leading to enhanced awareness about the benefits of getting vaccinated against COVID-19. The social and behavioral factors that gave rise to significantly low vaccine-acceptance rates, particularly in Asia and Africa, comprised of low levels of education, awareness and inefficient efforts and initiatives by the government that led to mistrust and perceived threats about the COVID-19 vaccine among the population. Furthermore, a poor history of influenza vaccination, conspiracy theories relating to infertility and misinformation about the COVID-19 vaccine on social-media platforms also resulted in vaccine hesitancy. One limitation of this systematic review is that it only includes studies reporting COVID-19 vaccine-acceptance rates and associated factors of fifty countries.

Hence, future research can be carried out with additional countries. Moreover, in order to optimize global COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, the governments should ensure that people become educated about the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination and should implement policies that help to elevate the awareness among the population. Moreover, the necessary elimination of conspiracy theories and misinformation regarding vaccination should also be ensured. This will ultimately lead to high COVID-19 vaccine acceptance all over the world and will aid in fighting and putting an end to this pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.S., M.S.M. and A.A.M.; methodology, C.S.S., M.S.M. and A.A.M.; supervision, S.J.K. and B.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.S., M.S.M. and A.A.M.; writing—review and editing, C.S.S., M.S.M., A.A.M., B.C. and S.J.K.; visualization, C.S.S., M.S.M., A.A.M., B.C. and S.J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pišot, S.; Milovanović, I.; Šimunič, B.; Gentile, A.; Bosnar, K.; Prot, F.; Bianco, A.; Lo Coco, G.; Bartoluci, S.; Katović, D.; et al. Maintaining everyday life praxis in the time of COVID-19 pandemic measures (ELP-COVID-19 survey). Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lades, L.K.; Laffan, K.; Daly, M.; Delaney, L. Daily emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, S.W.; Henkhaus, L.E.; Zickafoose, J.S.; Lovell, K.; Halvorson, A.; Loch, S.; Letterie, M.; Davis, M.M. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics 2020, 146, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, F.; Awan, T.M.; Syed, J.H.; Kashif, A.; Parveen, M. Sentiments and emotions evoked by news headlines of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2020, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dariya, B.; Nagaraju, G.P. Understanding novel COVID-19: Its impact on organ failure and risk assessment for diabetic and cancer patients. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 53, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, M.A. What we know so far: COVID-19 current clinical knowledge and research. Clin. Med. 2020, 20, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dey, S.K.; Rahman, M.M.; Siddiqi, U.R.; Howlader, A. Analyzing the epidemiological outbreak of COVID-19: A visual exploratory data analysis approach. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, D. COVID-19 lockdowns throughout the world. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Ahmadi, A.; Karimi, B. Multi-Objective Optimization of Home Healthcare with Working-Time Balancing and Care Continuity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R.; Smith, N.R. Bi-level programming for home health care supply chain considering outsourcing. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2021, 25, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Quteimat, O.M.; Amer, A.M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer patients. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 43, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.; Anderson, M.; Carter, P.; Ebert, B.L.; Mossialos, E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Nat. Cancer 2020, 1, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafaghi, A.H.; Talabazar, F.R.; Koşar, A.; Ghorbani, M. On the effect of the respiratory droplet generation condition on COVID-19 transmission. Fluids 2020, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deprest, J.; Choolani, M.; Chervenak, F.; Farmer, D.; Lagrou, K.; Lopriore, E.; McCullough, L.; Olutoye, O.; Simpson, L.; Van Mieghem, T.; et al. Fetal diagnosis and therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: Guidance on behalf of the international fetal medicine and surgery society. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2020, 47, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caparros-Gonzalez, R.A.; Ganho-Ávila, A.; Torre-Luque, A.d.l. The COVID-19 Pandemic Can Impact Perinatal Mental Health and the Health of the Offspring; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sade, S.; Sheiner, E.; Wainstock, T.; Hermon, N.; Yaniv Salem, S.; Kosef, T.; Lanxner Battat, T.; Oron, S.; Pariente, G. Risk for depressive symptoms among hospitalized women in high-risk pregnancy units during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceulemans, M.; Hompes, T.; Foulon, V. Mental health status of pregnant and breastfeeding women during the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 151, 146–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, L.C.; Zieff, G.; Stanford, K.; Moore, J.B.; Kerr, Z.Y.; Hanson, E.D.; Barone Gibbs, B.; Kline, C.E.; Stoner, L. COVID-19 impact on behaviors across the 24-h day in children and adolescents: Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. Children 2020, 7, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, A.; Oros, V.; Marca-Ghaemmaghami, P.L.; Scholkmann, F.; Righini-Grunder, F.; Natalucci, G.; Karen, T.; Bassler, D.; Restin, T. New parents experienced lower parenting self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Children 2021, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-L.; McAleer, M.; Wong, W.-K. Risk and Financial Management of COVID-19 in Business, Economics and Finance; Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, D.R. Health policy and technology challenges in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy Technol. 2020, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrup, A.; Kanaujia, R.; Ray, P.; Biswal, M. Healthcare facilities in low-and middle-income countries affected by COVID-19: Time to upgrade basic infection control and prevention practices. Indian J. Med. Microb. 2020, 38, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoorthy, M.S.; Pratapa, S.K.; Mahant, S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-19 pandemic–A review. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzittofis, A.; Karanikola, M.; Michailidou, K.; Constantinidou, A. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Healthcare Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreadakis, Z.; Kumar, A.; Román, R.G.; Tollefsen, S.; Saville, M.; Mayhew, S. The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 305–306. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B.S. Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development. Science 2020, 368, 945–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, S.; Ou, J.; Zhang, J.; Lan, W.; Guan, W.; Wu, X.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wu, J.; et al. COVID-19: Vaccine Development Updates. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Pang, Y.; Lyu, Z.; Wang, R.; Wu, X.; You, C.; Zhao, H.; Manickam, S.; Lester, E.; Wu, T.; et al. The COVID-19 vaccines: Recent development, challenges and prospects. Vaccines 2021, 9, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Dowling, W.E.; Román, R.G.; Chaudhari, A.; Gurry, C.; Le, T.T.; Tollefson, S.; Clark, C.E.; Bernasconi, V.; Kristiansen, P.A. Status report on COVID-19 vaccines development. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2021, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prüβ, B.M. Current state of the first COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccines 2021, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, D.K.A.; Farhana, K.M. Knowledge, attitude and acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine: A global cross-sectional study. Int. Res. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleszko, W.; Lewulis, P.; Czarnecki, A. Waszkiewicz Flattening the curve of COVID-19 vaccine rejection—An international overview. Vaccines 2021, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Ratzan, S.C.; Palayew, A.; Gostin, L.O.; Larson, H.J.; Rabin, K.; Kimball, S.; El-Mohandes, A. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, S.A.; Faria de Moura Villela, E.; Siau, C.S.; Chen, W.S.; Pengpid, S.; Hasan, M.T.; Sessou, P.; Ditekemena, J.D.; Amodan, B.O.; Hosseinipour, M.C.; et al. Factors Affecting COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance: An International Survey among Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: A concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines 2021, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, A.D. The Willingness to Receive COVID-19 Vaccine and Its Associated Factors: Vaccination Refusal Could Prolong the War of This Pandemic A Systematic Review. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 2609–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selçuk, A.A. A guide for systematic reviews: PRISMA. Turk. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 57, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Long, S.; Fu, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; Xiu, S.; Wang, X.; Lu, B.; Jin, H. Non-EPI Vaccine Hesitancy among Chinese Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhou, Y.-H. Real-World Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccines among Healthcare Workers in Perinatal Medicine in China. Vaccines 2021, 9, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Nicholas, S.; Leng, A.; Maitland, E.; Wang, J. COVID-19 Vaccination Willingness among Chinese Adults under the Free Vaccination Policy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, L.; Chen, Y.; Hu, P.; Wu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Tan, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D. Willingness to receive SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and associated factors among Chinese adults: A cross sectional survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.N.; Zhang, T.; Peng, X.Q.; Ge, J.J.; Gu, H.; You, H. Vaccine Acceptance and Its Influencing Factors: An Online Cross-Sectional Study among International College Students Studying in China. Vaccines 2021, 9, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Cao, M.; Xiang, T.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Dai, H. Will Healthcare Workers Accept a COVID-19 Vaccine When It Becomes Available? A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Wang, R.; Han, N.; Liu, J.; Yuan, C.; Deng, L.; Han, C.; Sun, F.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in China: A multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Wen, Z.; Feng, F.; Zou, H.; Fu, C.; Chen, L.; Shu, Y.; Sun, C. An online survey of the attitude and willingness of Chinese adults to receive COVID-19 vaccination. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 2279–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Francis, M.R.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Q.; Xia, A.; Lu, L.; Yang, B.; Hou, Z. Confidence, Acceptance and Willingness to Pay for the COVID-19 Vaccine among Migrants in Shanghai, China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayed, A.A.; Al Shahrani, A.S.; Almanea, L.T.; Alsweed, N.I.; Almarzoug, L.M.; Almuwallad, R.I.; Almugren, W.F. Willingness to Receive the COVID-19 and Seasonal Influenza Vaccines among the Saudi Population and Vaccine Uptake during the Initial Stage of the National Vaccination Campaign: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2021, 9, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qattan, A.M.N.; Alshareef, N.; Alsharqi, O.; al Rahahleh, N.; Chirwa, G.C.; Al-Hanawi, K.M. Acceptability of a COVID-19 Vaccine Among Healthcare Workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfageeh, E.I.; Alshareef, N.; Angawi, K.; Alhazmi, F.; Chirwa, G.C. Acceptability of a COVID-19 Vaccine among the Saudi Population. Vaccines 2021, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, S.M.; Dehom, S.; Almutairi, D.; Alnasser, B.S.; Alsaif, B.; Alabdrabalnabi, A.A.; Bin Rahmah, A.; Alshahrani, M.S.; El-Metwally, A.; Al-Khateeb, B.F.; et al. Acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study using a web-based survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 3338–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadhi, E.A.; Zein, D.; Mallallah, F.; Haider, N.B.; Hossain, A. Monitoring COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Kuwait During the Pandemic: Results from a National Serial Study. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 1413–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqudeimat, Y.; Alenezi, D.; AlHajri, B.; Alfouzan, H.; Almokhaizeem, Z.; Altamimi, S.; Almansouri, W.; Alzalzalah, S.; Ziyab, A.H. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and its related determinants among the general adult population in Kuwait. Med. Princ. Pract. 2021, 30, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Sanafi, M.; Sallam, M. Psychological Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance among Healthcare Workers in Kuwait: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the 5C and Vaccine Conspiracy Beliefs Scales. Vaccines 2021, 9, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M.; Dababseh, D.; Eid, H.; Al-Mahzoum, K.; Al-Haidar, A.; Taim, D.; Yaseen, A.; Ababneh, N.A.; Bakri, F.G.; Mahafzah, A. High rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and its association with conspiracy beliefs: A study in Jordan and Kuwait among other Arab countries. Vaccines 2021, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qerem, W.A.; Jarab, A.S. COVID-19 Vaccination Acceptance and Its Associated Factors Among a Middle Eastern Population. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Elimat, T.; AbuAlSamen, M.M.; Almomani, B.A.; Al-Sawalha, N.A.; Alali, F.Q. Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: A cross-sectional study from Jordan. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, E.; Lai, D.W.; Lee, V.W. Predictors of Intention to Vaccinate against COVID-19 in the General Public in Hong Kong: Findings from a Population-Based, Cross-Sectional Survey. Vaccines 2021, 9, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luk, T.T.; Zhao, S.; Wu, Y.; Wong, J.Y.-h.; Wang, M.P.; Lam, T.H. Prevalence and determinants of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy in Hong Kong: A population-based survey. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3602–3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.O.; Li, K.-K.; Wei, W.I.; Tang, A.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Lee, S.S. Influenza vaccine uptake, COVID-19 vaccination intention and vaccine hesitancy among nurses: A survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 114, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, M.; Nakamura, I.; Kojima, T.; Saito, R.; Nakaya, T.; Hanibuchi, T.; Takamiya, T.; Odagiri, Y.; Fukushima, N.; Kikuchi, H.; et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Japan during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Vaccines 2021, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoda, T.; Katsuyama, H. Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in Japan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, F.A.; Ahmad, B.; Khalid, M.D.; Fazal, A.; Javaid, M.M.; Butt, Q.D. Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and acceptance among the Pakistani population. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 3365–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, M.S.; Hussain, I.; Mahmood, T.; Hayat, K.; Majeed, A.; Imran, I.; Saeed, H.; Iqbal, M.O.; Uzair, M.; Ashraf, W.; et al. A National Survey to Assess the COVID-19 Vaccine-Related Conspiracy Beliefs, Acceptability, Preference, and Willingness to Pay among the General Population of Pakistan. Vaccines 2021, 9, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mulla, R.; Abu-Madi, M.; Talafha, Q.M.; Tayyem, R.F.; Abdallah, A.M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in a Representative Education Sector Population in Qatar. Vaccines 2021, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedin, M.; Islam, M.A.; Rahman, F.N.; Reza, H.M.; Hossain, M.Z.; Hossain, M.A.; Arefin, A.; Hossain, A. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 among Bangladeshi adults: Understanding the strategies to optimize vaccination coverage. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Halabi, C.K.; Obeid, S.; Sacre, H.; Akel, M.; Hallit, R.; Salameh, P.; Hallit, S. Attitudes of Lebanese adults regarding COVID-19 vaccination. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Metwali, B.Z.; Al-Jumaili, A.A.; Al-Alag, Z.A.; Sorofman, B. Exploring the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare workers and general population using health belief model. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2021, 27, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, O.; Zamlout, A.; AlKhoury, N.; Mazloum, A.; Alsalkini, M.; Shaaban, R. Factors associated with the intention of Syrian adult population to accept COVID19 vaccination: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabi, R.; Maraqa, B.; Nazzal, Z.; Zink, T. Factors affecting nurses’ intention to accept the COVID-9 vaccine: A cross-sectional study. Public Health Nurs. 2021, 38, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigron, A.; Dror, A.A.; Morozov, N.; Shani, T.; Haj Khalil, T.; Eisenbach, N.; Rayan, D.; Daoud, A.; Kablan, F.; Sela, E.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among dental professionals based on employment status during the pandemic. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.L.; Hu, Z.J.; Zhao, Q.J.; Alias, H.; Danaee, M.; Wong, L.P. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine demand and hesitancy: A nationwide online survey in China. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jing, R.; Lai, X.; Zhang, H.; Lyu, Y.; Knoll, M.D.; Fang, H. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines 2020, 8, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.C.; Fang, Y.; Cao, H.; Chen, H.; Hu, T.; Chen, Y.Q.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Z. Parental acceptability of COVID-19 vaccination for children under the age of 18 years: Cross-sectional online survey. Jmir Pediatr. Parent. 2020, 3, e24827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Ho, K.F.; Cheung, A.W.L.; Chan, E.Y.Y.; Yeoh, E.K.; Wong, S.Y.S. Intention of nurses to accept coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination and change of intention to accept seasonal influenza vaccination during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A cross-sectional survey. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7049–7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harapan, H.; Wagner, A.L.; Yufika, A.; Winardi, W.; Anwar, S.; Gan, A.K.; Setiawan, A.M.; Rajamoorthy, Y.; Sofyan, H.; Mudatsir, M. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine in Southeast Asia: A cross-sectional study in Indonesia. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mohaithef, M.; Padhi, B.K. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia: A web-based national survey. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2020, 13, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, A.A.; Eisenbach, N.; Taiber, S.; Morozov, N.G.; Mizrachi, M.; Zigron, A.; Srouji, S.; Sela, E. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Alias, H.; Wong, P.-F.; Lee, H.Y.; AbuBakar, S. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to pay. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedele, F.; Aria, M.; Esposito, V.; Micillo, M.; Cecere, G.; Spano, M.; De Marco, G. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: A survey in a population highly compliant to common vaccinations. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Murri, R.; Segala, F.V.; Cerruti, L.; Abdulle, A.; Saracino, A.; Bavaro, D.F.; Fantoni, M. Attitudes towards Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination among Healthcare Workers: Results from a National Survey in Italy. Viruses 2021, 13, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Riccio, M.; Boccalini, S.; Rigon, L.; Biamonte, M.A.; Albora, G.; Giorgetti, D.; Bonanni, P.; Bechini, A. Factors Influencing SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy in a Population-Based Sample in Italy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucco Aurilio, M.; Mennini, F.S.; Gazzillo, S.; Massini, L.; Bolcato, M.; Feola, A.; Ferrari, C.; Coppeta, L. Intention to be vaccinated for COVID-19 among Italian nurses during the pandemic. Vaccines 2021, 9, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guaraldi, F.; Montalti, M.; Di Valerio, Z.; Mannucci, E.; Nreu, B.; Monami, M.; Gori, D. Rate and Predictors of Hesitancy toward SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine among Type 2 Diabetic Patients: Results from an Italian Survey. Vaccines 2021, 9, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Giuseppe, G.; Pelullo, C.P.; della Polla, G.; Pavia, M.; Angelillo, I.F. Exploring the willingness to accept SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in a University population in Southern Italy, September to November 2020. Vaccines 2021, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- İkiışık, H.; Sezerol, M.A.; Taşçı, Y.; Maral, I. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy: A Community-Based Research in Turkey. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, M.; Ozkaya-Parlakay, A.; Senel, E. Evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance of healthcare providers in a tertiary Pediatric hospital. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurttas, B.; Poyraz, B.C.; Sut, N.; Ozdede, A.; Oztas, M.; Uğurlu, S.; Tabak, F.; Hamuryudan, V.; Seyahi, E. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine among patients with rheumatic diseases, healthcare workers and general population in Turkey: A web-based survey. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.; Flowers, P.; McLeod, J.; Young, D.; Rollins, L. Social patterning and stability of intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine in Scotland: Will those most at risk accept a vaccine? Vaccines 2021, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakonti, G.; Kyprianidou, M.; Toumbis, G.; Giannakou, K. Attitudes and Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination Among Nurses and Midwives in Cyprus: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannis, D.; Rachiotis, G.; Malli, F.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Kotsiou, O.; Fradelos, E.C.; Giannakopoulos, K.; Gourgoulianis, K.I. Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccination among Greek Health Professionals. Vaccines 2021, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzinger, M.; Watson, V.; Arwidson, P.; Alla, F.; Luchini, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: A survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, E210–E221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneux-Brunon, A.; Detoc, M.; Bruel, S.; Tardy, B.; Rozaire, O.; Frappe, P.; Botelho-Nevers, E. Intention to get vaccinations against COVID-19 in French healthcare workers during the first pandemic wave: A cross-sectional survey. J. Hosp. Infect. 2021, 108, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Smith, L.E.; Sim, J.; Amlôt, R.; Cutts, M.; Dasch, H.; Rubin, G.J.; Sevdalis, N. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: Results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann-Böhme, S.; Varghese, N.E.; Sabat, I.; Barros, P.P.; Brouwer, W.; van Exel, J.; Schreyögg, J.; Stargardt, T. Once We Have It, Will We Use It? A European Survey on Willingness to Be Vaccinated against COVID-19; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, D.; Loe, B.S.; Chadwick, A.; Vaccari, C.; Waite, F.; Rosebrock, L.; Jenner, L.; Petit, A.; Lewandowsky, S.; Vanderslott, S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: The Oxford coronavirus explanations, attitudes, and narratives survey (Oceans) II. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Clarke, R.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Walker, J.L.; Paterson, P. Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: A multi-methods study in England. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7789–7798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salali, G.D.; Uysal, M.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is associated with beliefs on the origin of the novel coronavirus in the UK and Turkey. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detoc, M.; Bruel, S.; Frappe, P.; Tardy, B.; Botelho-Nevers, E.; Gagneux-Brunon, A. Intention to participate in a COVID-19 vaccine clinical trial and to get vaccinated against COVID-19 in France during the pandemic. Vaccine 2020, 38, 7002–7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, J.K.; Alleaume, C.; Peretti-Watel, P.; Seror, V.; Cortaredona, S.; Launay, O.; Raude, J.; Verger, P.; Beck, F.; Legleye, S.; et al. The French public’s attitudes to a future COVID-19 vaccine: The politicization of a public health issue. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 265, 113414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Vecchia, C.; Negri, E.; Alicandro, G.; Scarpino, V. Attitudes towards influenza vaccine and a potential COVID-19 vaccine in Italy and differences across occupational groups, September 2020. Med. Lav. 2020, 111, 445. [Google Scholar]

- Barello, S.; Nania, T.; Dellafiore, F.; Graffigna, G.; Caruso, R. ‘Vaccine hesitancy’among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, A.R.; Kepka, D.; Ramsay, J.M.; Mann, K.; Vaca Lopez, P.L.; Anderson, J.S.; Ou, J.Y.; Kaddas, H.K.; Palmer, A.; Ray, N.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Among Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Survivors. JNCI Can. Spectr. 2021, 5, pkab049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, A.K.; Lucia, V.C.; Kelekar, A.; Afonso, N.M. Dental students’ attitudes and hesitancy toward COVID-19 vaccine. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanath, K.; Bekalu, M.; Dhawan, D.; Pinnamaneni, R.; Lang, J.N.; McLoud, R. Individual and social determinants of COVID-19 vaccine uptake. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogue, K.; Jensen, J.L.; Stancil, C.K.; Ferguson, D.G.; Hughes, S.J.; Mello, E.J.; Burgess, R.; Berges, B.K.; Quaye, A.; Poole, B.D. Influences on Attitudes Regarding Potential COVID-19 Vaccination in the United States. Vaccines 2020, 8, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.A.; Bloomstone, S.J.; Walder, J.; Crawford, S.; Fouayzi, H.; Mazor, K.M. Attitudes Toward a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine A Survey of US Adults. Ann. Int. Med. 2020, 173, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.A.; McFadden, S.M.; Elharake, J.; Omer, S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EclinicalMedicine 2020, 26, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, P.L.; Pennell, M.L.; Katz, M.L. Acceptability of a COVID-19 vaccine among adults in the United States: How many people would get vaccinated? Vaccine 2020, 38, 6500–6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Groenewoud, R.; Rachor, G.S.; Asmundson, G.J. A proactive approach for managing COVID-19: The importance of understanding the motivational roots of vaccination hesitancy for SARS-CoV-2. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seale, H.; Heywood, A.E.; Leask, J.; Sheel, M.; Durrheim, D.N.; Bolsewicz, K.; Kaur, R. Examining Australian public perceptions and behaviors towards a future COVID-19 vaccine. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A.; Hoq, M.; Measey, M.-A.; Danchin, M. Intention to vaccinate against COVID-19 in Australia. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, O.V.; Stead, D.; Singata-Madliki, M.; Batting, J.; Wright, M.; Jelliman, E.; Abrahams, S.; Parrish, A. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccine among the Healthcare Workers in the Eastern Cape, South Africa: A Cross Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saied, S.M.; Saied, E.M.; Kabbash, I.A.; Abdo, S.A. Vaccine hesitancy: Beliefs and barriers associated with COVID-19 vaccination among Egyptian medical students. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 4280–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzaji, M.K.; Ngombe, L.K.; Mwamba, G.N.; Ndala, D.B.B.; Miema, J.M.; Lungoyo, C.L.; Mwimba, B.L.; Bene, A.C.M.; Musenga, E.M. Acceptability of vaccination against COVID-19 among healthcare workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pragmatic Obs. Res. 2020, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, A.A.; Garcia, L.Y. Hesitation and Refusal Factors in Individuals’ Decision-Making Processes Regarding a Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasty, O.; Carpio, C.E.; Hudson, D.; Guerrero-Ochoa, P.A.; Borja, I. The demand for a COVID-19 vaccine in Ecuador. Vaccine 2020, 38, 8090–8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyranoski, D. What China’s speedy COVID vaccine deployment means for the pandemic. Nature 2020, 586, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machingaidze, S.; Wiysonge, C.S. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R.A.; Osborne, R.H.; Yongabi, K.A.; Greenhalgh, T.; Gurdasani, D.; Kang, G.; Falade, A.G.; Odone, A.; Busse, R.; Martin-Moreno, J.M.; et al. The COVID-19 vaccines rush: Participatory community engagement matters more than ever. Lancet 2021, 397, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoch-Spana, M.; Brunson, E.K.; Long, R.; Ruth, A.; Ravi, S.J.; Trotochaud, M.; Borio, L.; Brewer, J.; Buccina, J.; Connell, N.; et al. The public’s role in COVID-19 vaccination: Human-centered recommendations to enhance pandemic vaccine awareness, access, and acceptance in the United States. Vaccine 2021, 39, 6004–6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuyakor, J.; Nyatuame, I.N.; Obiri, S. Unmasking COVID-19 Vaccine Infodemic in the Social Media. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2021, 11, e202119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).