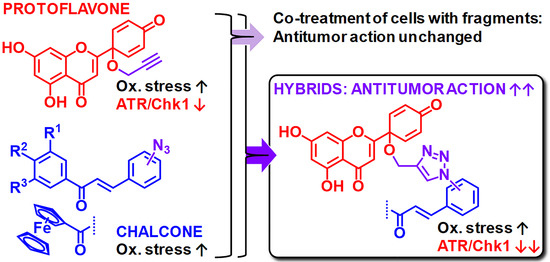

Protoflavone-Chalcone Hybrids Exhibit Enhanced Antitumor Action through Modulating Redox Balance, Depolarizing the Mitochondrial Membrane, and Inhibiting ATR-Dependent Signaling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General

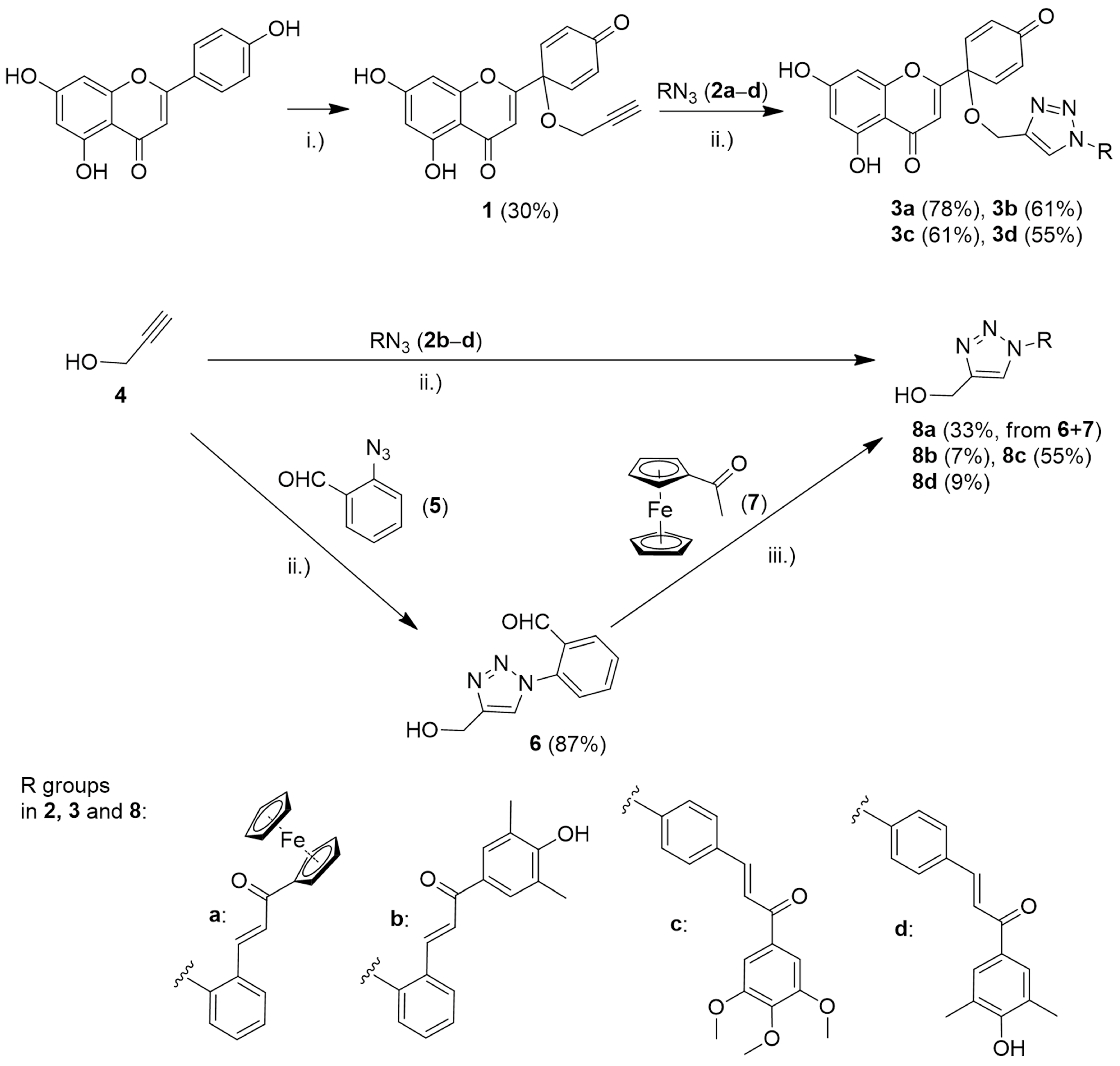

2.2. Synthesis of Compound 1 from Apigenin

2.3. Synthesis of Hybrid Compounds 3a–d

2.4. Synthesis of the Reference Fragment 8a

2.4.1. (a) Synthesis of 2-(4-(Hydroxymethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)benzaldehyde (6)

2.4.2. (b) Synthesis of (E)-1-Ferrocenyl-3-(2-(4-(hydroxymethyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazole-1-yl)phenyl)prop-2-en-1-one (8a)

2.5. Synthesis of Reference Fragments 8b–d

2.6. Spectrofluorimetric Investigation of Compounds 3a–d

2.7. Cell Lines

2.8. Cell Viability Assay

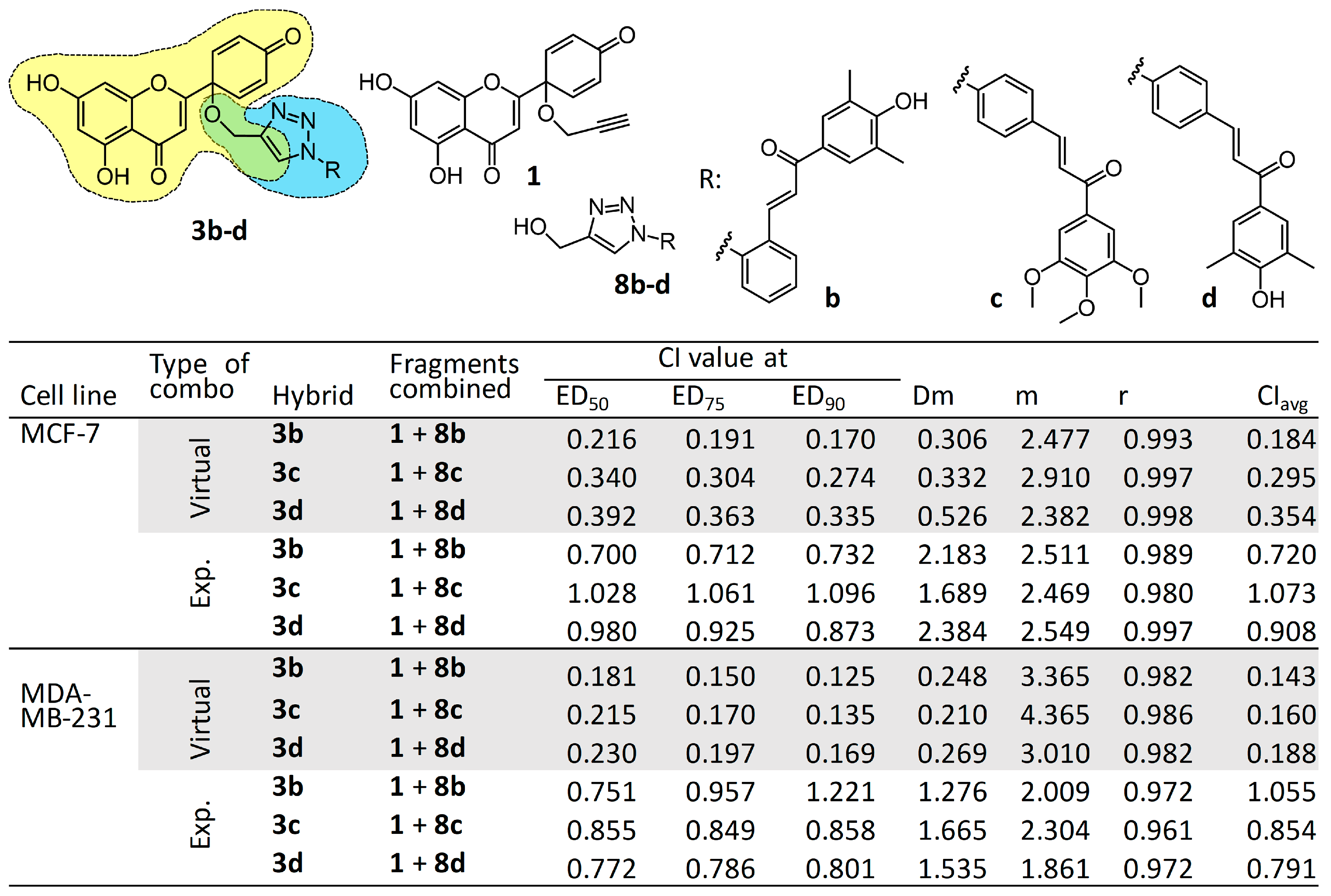

2.9. Combination Study of Relevant Fragments Compared with Their Hybrids 3b–d

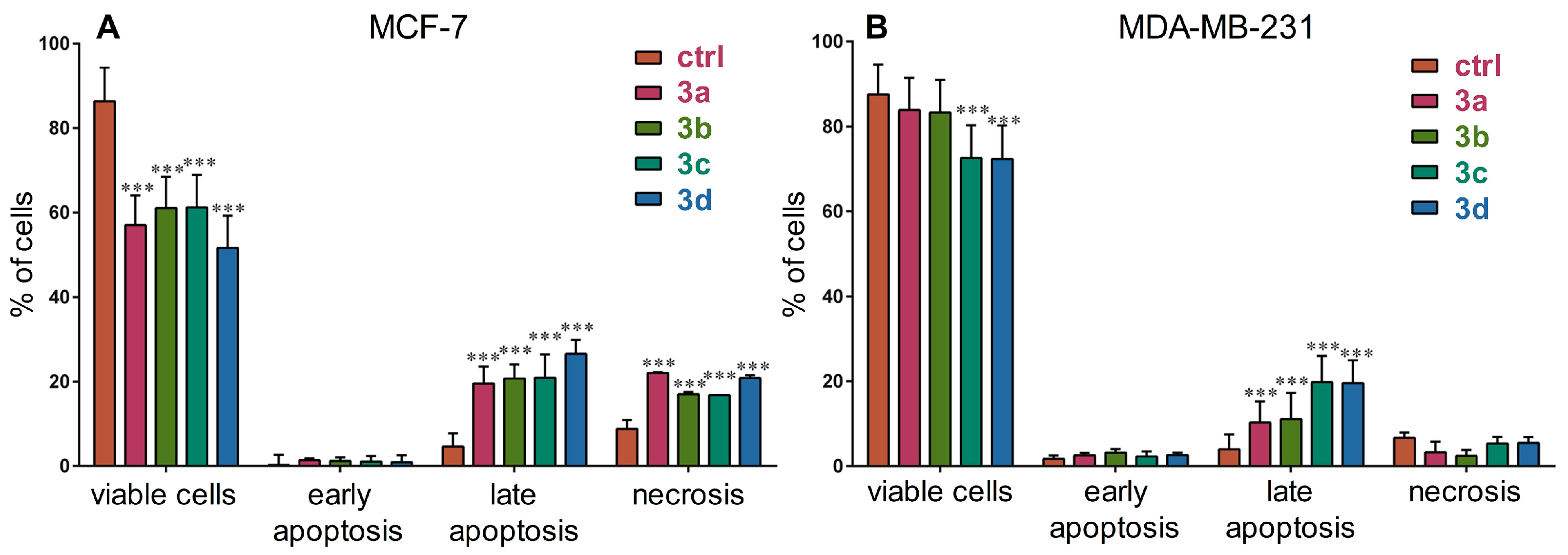

2.10. Cell Death Analysis

2.11. Cell Cycle Analysis in MDA-MB-231 Cells

2.12. Effect of Compound 3c on Caspase-3 Activity in MDA-MB-231 Cells

2.13. Effect of Compounds 3a–d on DNA Damage Response

2.14. Effect of Compounds 3a–d on ROS/RNS Levels

2.15. Assessing Mitochondrial Membrane Depolarization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Cell Viability Assay, Virtual and Experimental Combination Study

3.3. Cell Death Induction Analysis

3.4. Cell Cycle Analysis and Effects of Compound 3c on Caspase-3 Activity in MDA-MB-231 Cells

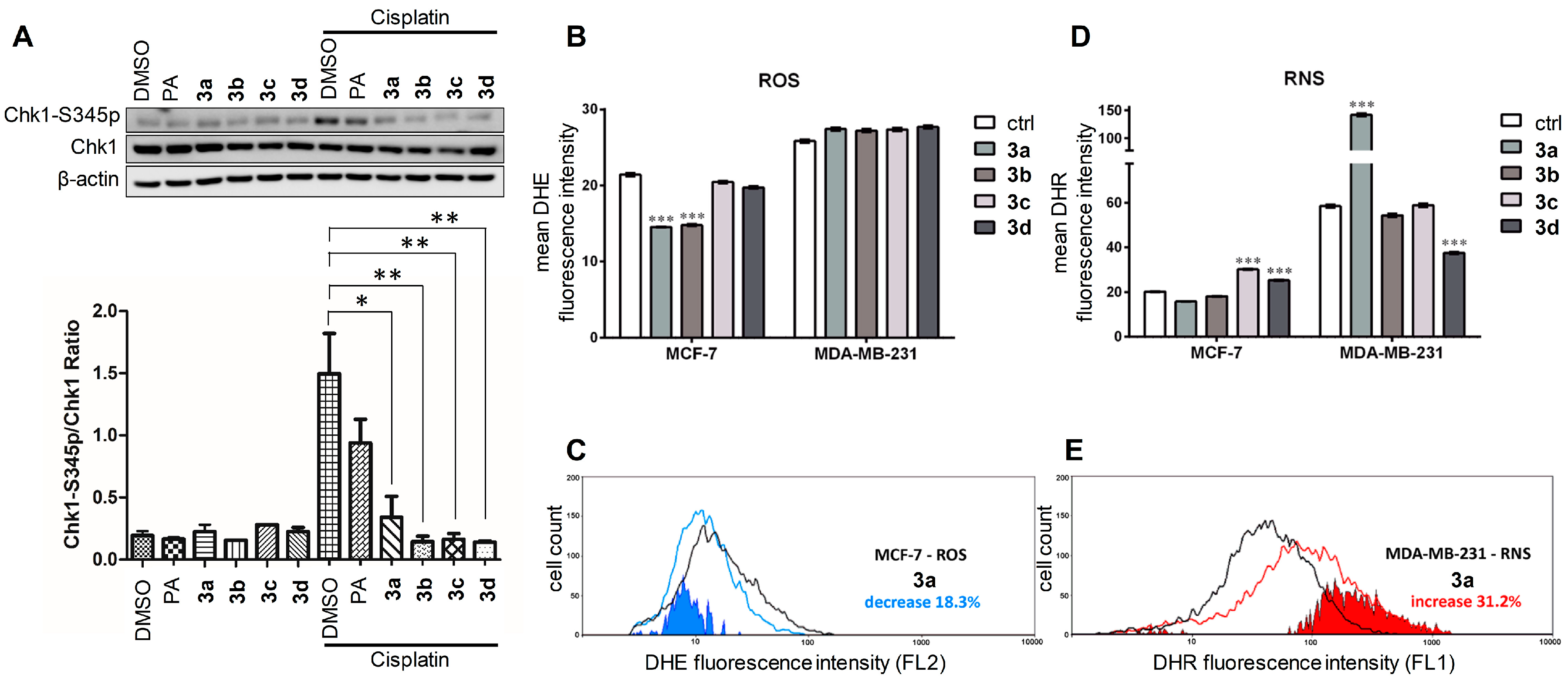

3.5. Effects of Compounds 3a–d on the ATR-Dependent Phosphorylation of Chk1

3.6. Effect on the Levels of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species

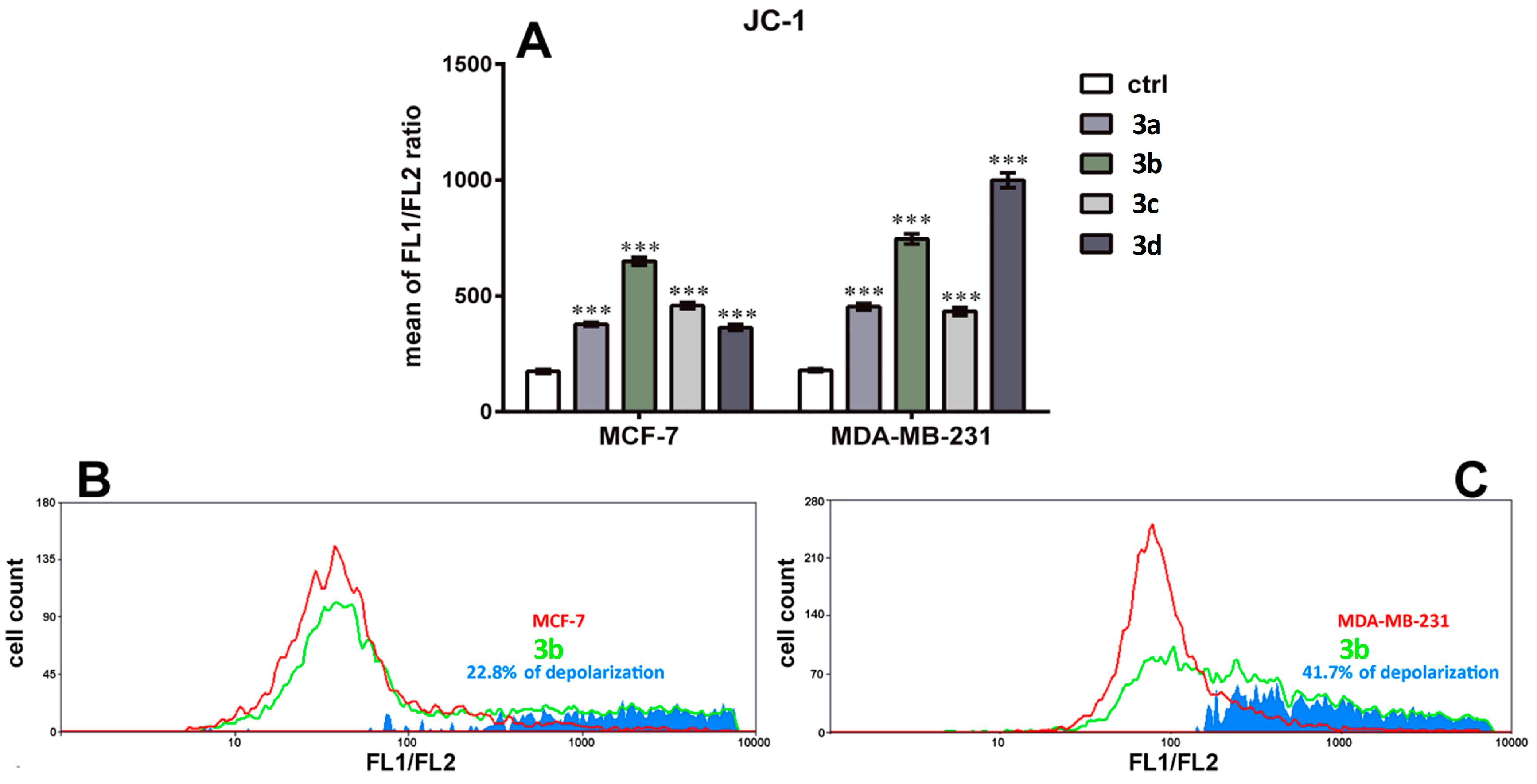

3.7. Effect on Mitochondrial Membrane Depolarization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Union for International Cancer Control. New Global Cancer Data: GLOBOCAN 2018. Available online: https://www.uicc.org/news/new-global-cancer-data-globocan-2018 (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Elder, E.E.; Kennedy, C.W.; Gluch, L.; Carmalt, H.L.; Janu, N.C.; Joseph, M.G.; Donellan, M.J.; Molland, J.G.; Gillett, D.J. Patterns of breast cancer relapse. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 32, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, S.B. How shall we treat early triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC): From the current standard to upcoming immuno-molecular strategies. ESMO Open 2018, 3, e000357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergin, A.R.T.; Loi, S. Triple-negative breast cancer: Recent treatment advances. F1000Research 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciana, S.; Francisco Jaime Bezerra, M.-J.; Marcus, T.S. Editorial (Thematic Issue: Hybrid Compounds as Multitarget Agents in Medicinal Chemistry–Part II). Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 957–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Pedrosa, M.; Duarte da Cruz, R.M.; de Oliveira Viana, J.; de Moura, R.O.; Ishiki, H.M.; Barbosa Filho, J.M.; Diniz, M.F.F.M.; Scotti, M.T.; Scotti, L.; Bezerra Mendonca, F.J. Hybrid Compounds as Direct Multitarget Ligands: A Review. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 1044–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizeh, A.; Jahan, B.G. Dual-acting of Hybrid Compounds–A New Dawn in the Discovery of Multi-target Drugs: Lead Generation Approaches. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 1096–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunyadi, A.; Martins, A.; Danko, B.; Chang, F.R.; Wu, Y.C. Protoflavones: A class of unusual flavonoids as promising novel anticancer agents. Phytochem. Rev. 2014, 13, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danko, B.; Martins, A.; Chuang, D.W.; Wang, H.C.; Amaral, L.; Molnar, J.; Chang, F.R.; Wu, Y.C.; Hunyadi, A. In vitro cytotoxic activity of novel protoflavone analogs–selectivity towards a multidrug resistant cancer cell line. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 2863–2870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pouny, I.; Etievant, C.; Marcourt, L.; Huc-Dumas, I.; Batut, M.; Girard, F.; Wright, M.; Massiot, G. Protoflavonoids from ferns impair centrosomal integrity of tumor cells. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranah, G.J.; Manini, T.M.; Lohman, K.K.; Nalls, M.A.; Kritchevsky, S.; Newman, A.B.; Harris, T.B.; Miljkovic, I.; Biffi, A.; Cummings, S.R.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA variation in human metabolic rate and energy expenditure. Mitochondrion 2011, 11, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-L.; Wu, Y.-C.; Su, J.-H.; Yeh, Y.-T.; Yuan, S.-S.F. Protoapigenone, a novel flavonoid, induces apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1/2. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 325, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.-S.; Chang, F.-R.; Wu, C.-C.; Liaw, C.-C.; Wu, Y.-C. New cytotoxic flavonoids from Thelypteris torresiana. Planta Med. 2005, 71, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Kay, N.; Yang, J.-M.; Lin, C.-T.; Chang, H.-L.; Wu, Y.-C.; Fu, C.-F.; Chang, Y.; Lo, S.; Hou, M.-F.; et al. Total synthetic protoapigenone WYC02 inhibits cervical cancer cell proliferation and tumour growth through PIK3 signalling pathway. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 113, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Chen, H.-P.; Cheng, Y.-J.; Lin, Y.-H.; Liu, K.-W.; Hou, M.-F.; Wu, Y.-C.; Lee, Y.-C.; Yuan, S.-S. The synthetic flavonoid WYC02-9 inhibits colorectal cancer cell growth through ROS-mediated activation of MAPK14 pathway. Life Sci. 2013, 92, 1081–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.C.; Lee, A.Y.; Chou, W.C.; Wu, C.C.; Tseng, C.N.; Liu, K.Y.; Lin, W.L.; Chang, F.R.; Chuang, D.W.; Hunyadi, A.; et al. Inhibition of ATR-dependent signaling by protoapigenone and its derivative sensitizes cancer cells to interstrand cross-link-generating agents in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2012, 11, 1443–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.L.; Su, J.H.; Yeh, Y.T.; Lee, Y.C.; Chen, H.M.; Wu, Y.C.; Yuan, S.S. Protoapigenone, a novel flavonoid, inhibits ovarian cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2008, 267, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.M.; Chang, F.R.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Cheng, Y.J.; Hsieh, K.C.; Tsai, L.M.; Lin, A.S.; Wu, Y.C.; Yuan, S.S. A novel synthetic protoapigenone analogue, WYC02-9, induces DNA damage and apoptosis in DU145 prostate cancer cells through generation of reactive oxygen species. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 1151–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y.; Hsieh, Y.A.; Tsai, C.I.; Kang, Y.F.; Chang, F.R.; Wu, Y.C.; Wu, C.C. Protoapigenone, a natural derivative of apigenin, induces mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent apoptosis in human breast cancer cells associated with induction of oxidative stress and inhibition of glutathione S-transferase pi. Investig. New Drugs 2011, 29, 1347–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, M.T.; Harrington, K.J. Targeting ATR for Cancer Therapy: ATR-Targeted Drug Candidates. In Targeting the DNA Damage Response for Anti-Cancer Therapy; Pollard, J., Curtin, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Manhattan, NY, USA, 26 May 2018; pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecona, E.; Fernandez-Capetillo, O. Targeting ATR in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, R.; Brown, J.; Ingles Russo, A.; Yap, T.A. Targeting ATR in cancer medicine. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2017, 41, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Sorrell, M.; Berman, Z. Functional interplay between ATM/ATR-mediated DNA damage response and DNA repair pathways in oxidative stress. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 3951–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijova, E. Bioavailability of chalcones. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2006, 107, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Kumar, R.; Kodwani, R.; Kapoor, S.; Khare, A.; Bansal, R.; Khurana, S.; Singh, S.; Thomas, J.; Roy, B.; et al. A Review on Mechanisms of Anti Tumor Activity of Chalcones. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2015, 16, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, C.; Moorthy, N.S.; Ramasamy, S.; Vanam, U.; Manivannan, E.; Karunagaran, D.; Trivedi, P. Advances in chalcones with anticancer activities. Recent Pat. Anti-Cancer Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatra, D.K.; Bharti, S.K.; Asati, V. Anti-cancer chalcones: Structural and molecular target perspectives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 98, 69–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, L.; Szabo, I.; Bosze, S.; Jernei, T.; Hudecz, F.; Csampai, A. Synthesis, structure and in vitro cytostatic activity of ferrocene-Cinchona hybrids. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolski-Renic, A.; Bosze, S.; Dinic, J.; Kocsis, L.; Hudecz, F.; Csampai, A.; Pesic, M. Ferrocene-cinchona hybrids with triazolyl-chalcone linkers act as pro-oxidants and sensitize human cancer cell lines to paclitaxel. Metallomics 2017, 9, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, M.; Gasser, G. The medicinal chemistry of ferrocene and its derivatives. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Tagle, R.; Escobar, C.A.; Romero, V.; Montorfano, I.; Armisén, R.; Borgna, V.; Jeldes, E.; Pizarro, L.; Simon, F.; Echeverria, C. Chalcone-Induced Apoptosis through Caspase-Dependent Intrinsic Pathways in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, M.B.; Bertholin Anselmo, D.; de Oliveira, J.G.; Jardim-Perassi, B.V.; Alves Monteiro, D.; Silva, G.; Gomes, E.; Lucia Fachin, A.; Marins, M.; de Campos Zuccari, D.A.P.; et al. Antiproliferative activity and p53 upregulation effects of chalcones on human breast cancer cells. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunyadi, A.; Chuang, D.W.; Danko, B.; Chiang, M.Y.; Lee, C.L.; Wang, H.C.; Wu, C.C.; Chang, F.R.; Wu, Y.C. Direct semi-synthesis of the anticancer lead-drug protoapigenone from apigenin, and synthesis of further new cytotoxic protoflavone derivatives. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupko, I.; Molnar, J.; Rethy, B.; Minorics, R.; Frank, E.; Wolfling, J.; Molnar, J.; Ocsovszki, I.; Topcu, Z.; Bito, T.; et al. Anticancer and multidrug resistance-reversal effects of solanidine analogs synthetized from pregnadienolone acetate. Molecules 2014, 19, 2061–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolov, M.; Ghiulai, R.M.; Voicu, M.; Mioc, M.; Duse, A.O.; Roman, R.; Ambrus, R.; Zupko, I.; Moaca, E.A.; Coricovac, D.E.; et al. Cocrystal Formation of Betulinic Acid and Ascorbic Acid: Synthesis, Physico-Chemical Assessment, Antioxidant, and Antiproliferative Activity. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roza, O.; Lai, W.C.; Zupkó, I.; Hohmann, J.; Jedlinszki, N.; Chang, F.R.; Csupor, D.; Eloff, J.N. Bioactivity guided isolation of phytoestrogenic compounds from Cyclopia genistoides by the pER8:GUS reporter system. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 110, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefkó, D.; Kúsz, N.; Csorba, A.; Jakab, G.; Bérdi, P.; Zupkó, I.; Hohmann, J.; Vasas, A. Phenanthrenes from Juncus atratus with antiproliferative activity. Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.C. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 621–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinka, I.; Kiss, A.; Mernyak, E.; Wolfling, J.; Schneider, G.; Ocsovszki, I.; Kuo, C.Y.; Wang, H.C.; Zupko, I. Antiproliferative and antimetastatic properties of 3-benzyloxy-16-hydroxymethylene-estradiol analogs against breast cancer cell lines. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 123, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyovai, A.; Minorics, R.; Kiss, A.; Mernyák, E.; Schneider, G.; Szekeres, A.; Kerekes, E.; Ocsovszki, I.; Zupkó, I. Antiproliferative Properties of Newly Synthesized 19-Nortestosterone Analogs Without Substantial Androgenic Activity. Front. Pharmcol. 2018, 9, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostovtsev, V.V.; Green, L.G.; Fokin, V.V.; Sharpless, K.B. A Stepwise Huisgen Cycloaddition Process: Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective “Ligation” of Azides and Terminal Alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 2596–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, C.L.; Walker-Jones, D.; Heckford, S.E.; Worland, P.; Valverius, E.; Clark, R.; McCormick, F.; Stampfer, M.; Abularach, S.; Gelmann, E.P. Vimentin rather than keratin expression in some hormone-independent breast cancer cell lines and in oncogene-transformed mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 1989, 49, 4258–4263. [Google Scholar]

- Soule, H.D.; Vazguez, J.; Long, A.; Albert, S.; Brennan, M. A human cell line from a pleural effusion derived from a breast carcinoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1973, 51, 1409–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visagie, M.H.; Mqoco, T.V.; Liebenberg, L.; Mathews, E.H.; Mathews, G.E.; Joubert, A.M. Influence of partial and complete glutamine-and glucose deprivation of breast-and cervical tumorigenic cell lines. Cell Biosci. 2015, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.-C.; Chang, H.-W.; Chuang, D.-W.; Chang, F.-R.; Chang, Y.-C.; Cheng, Y.-S.; Tsai, M.-T.; Chen, W.-Y.; Lee, S.-S.; Wang, C.-K.; et al. Fern Plant–Derived Protoapigenone Leads to DNA Damage, Apoptosis, and G2/M Arrest in Lung Cancer Cell Line H1299. DNA Cell Biol. 2009, 28, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F.; Becker, S.; Classen, S.; Parplys, A.C.; Mansour, W.Y.; Riepen, B.; Timm, S.; Ruebe, C.; Jasin, M.; Wikman, H.; et al. Prevention of DNA Replication Stress by CHK1 Leads to Chemoresistance Despite a DNA Repair Defect in Homologous Recombination in Breast Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, M.; Eeles, R.; Hollstein, M.; Khan, M.A.; Harris, C.C.; Hainaut, P. The IARC TP53 database: New online mutation analysis and recommendations to users. Hum. Mutat. 2002, 19, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Errington, J.; Curtin, N.J.; Lunec, J.; Newell, D.R. The impact of p53 status on cellular sensitivity to antifolate drugs. Clin. Cancer Res. 2001, 7, 2114–2123. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, F.K.; Pollard, J.R.; Curtin, N.J. The Impact of p53 Dysfunction in ATR Inhibitor Cytotoxicity and Chemo- and Radiosensitisation. Cancers 2018, 10, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Xu, H.N.; Luo, Q.; Li, L.Z. Potential Indexing of the Invasiveness of Breast Cancer Cells by Mitochondrial Redox Ratios. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 923, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodossiou, T.A.; Wälchli, S.; Olsen, C.E.; Skarpen, E.; Berg, K. Deciphering the Nongenomic, Mitochondrial Toxicity of Tamoxifens As Determined by Cell Metabolism and Redox Activity. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodossiou, T.A.; Olsen, C.E.; Jonsson, M.; Kubin, A.; Hothersall, J.S.; Berg, K. The diverse roles of glutathione-associated cell resistance against hypericin photodynamic therapy. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Tielas, C.; Graña, E.; Reigosa, M.J.; Sánchez-Moreiras, A.M. Biological activities and novel applications of chalcones. Planta Daninha 2016, 34, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.I.; Lim, S.S.; Choi, H.J.; Cho, H.J.; Shin, H.K.; Kim, E.J.; Chung, W.Y.; Park, K.K.; Park, J.H. Isoliquiritigenin induces apoptosis by depolarizing mitochondrial membranes in prostate cancer cells. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006, 17, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| IC50 [95% CI] (µM) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 |

| 1 | 1.74 [1.55–1.95] | 2.53 [2.34–2.72] |

| 8aa | >20 | >20 |

| 8b | 15.07 [13.66–16.64] | 11.11 [10.53–11.71] |

| 8c | 2.51 [2.24–2.82] | 4.40 [3.98–4.86] |

| 8d | 11.00 [10.20–11.85] | 4.92 [4.52–5.36] |

| 3a | 0.47 [0.45–0.49] | 0.37 [0.36–0.39] |

| 3b | 0.25 [0.23–0.28] | 0.29 [0.27–0.31] |

| 3c | 0.30 [0.27–0.32] | 0.22 [0.21–0.24] |

| 3d | 0.51 [0.48–0.55] | 0.32 [0.30–0.35] |

| Cisplatin | 5.35 [4.97–5.76] | 26.15 b [24.18–28.27] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Latif, A.D.; Jernei, T.; Podolski-Renić, A.; Kuo, C.-Y.; Vágvölgyi, M.; Girst, G.; Zupkó, I.; Develi, S.; Ulukaya, E.; Wang, H.-C.; et al. Protoflavone-Chalcone Hybrids Exhibit Enhanced Antitumor Action through Modulating Redox Balance, Depolarizing the Mitochondrial Membrane, and Inhibiting ATR-Dependent Signaling. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9060519

Latif AD, Jernei T, Podolski-Renić A, Kuo C-Y, Vágvölgyi M, Girst G, Zupkó I, Develi S, Ulukaya E, Wang H-C, et al. Protoflavone-Chalcone Hybrids Exhibit Enhanced Antitumor Action through Modulating Redox Balance, Depolarizing the Mitochondrial Membrane, and Inhibiting ATR-Dependent Signaling. Antioxidants. 2020; 9(6):519. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9060519

Chicago/Turabian StyleLatif, Ahmed Dhahir, Tamás Jernei, Ana Podolski-Renić, Ching-Ying Kuo, Máté Vágvölgyi, Gábor Girst, István Zupkó, Sedef Develi, Engin Ulukaya, Hui-Chun Wang, and et al. 2020. "Protoflavone-Chalcone Hybrids Exhibit Enhanced Antitumor Action through Modulating Redox Balance, Depolarizing the Mitochondrial Membrane, and Inhibiting ATR-Dependent Signaling" Antioxidants 9, no. 6: 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9060519

APA StyleLatif, A. D., Jernei, T., Podolski-Renić, A., Kuo, C.-Y., Vágvölgyi, M., Girst, G., Zupkó, I., Develi, S., Ulukaya, E., Wang, H.-C., Pešić, M., Csámpai, A., & Hunyadi, A. (2020). Protoflavone-Chalcone Hybrids Exhibit Enhanced Antitumor Action through Modulating Redox Balance, Depolarizing the Mitochondrial Membrane, and Inhibiting ATR-Dependent Signaling. Antioxidants, 9(6), 519. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9060519