Next-Generation Antioxidants in Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanistic Insights and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

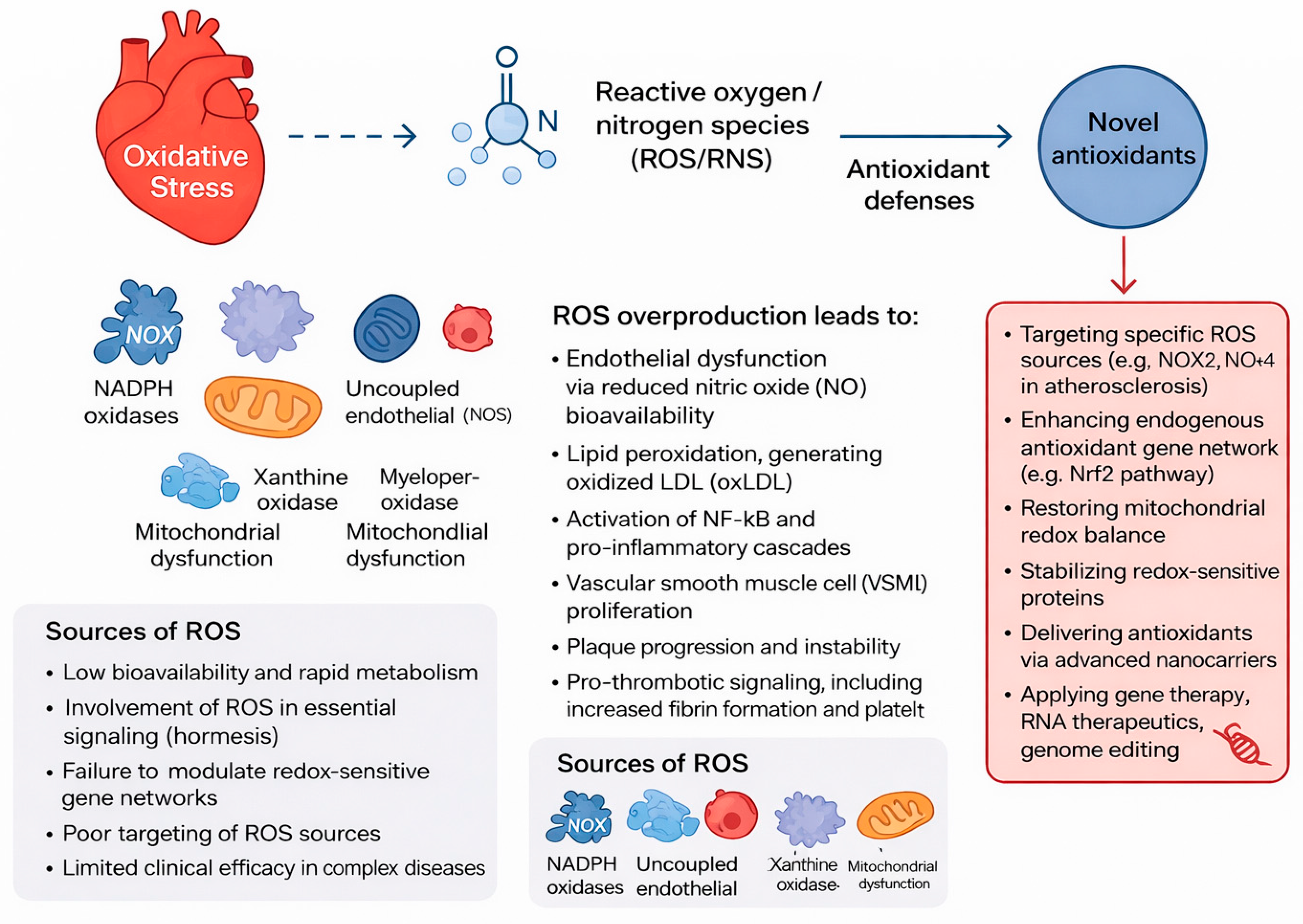

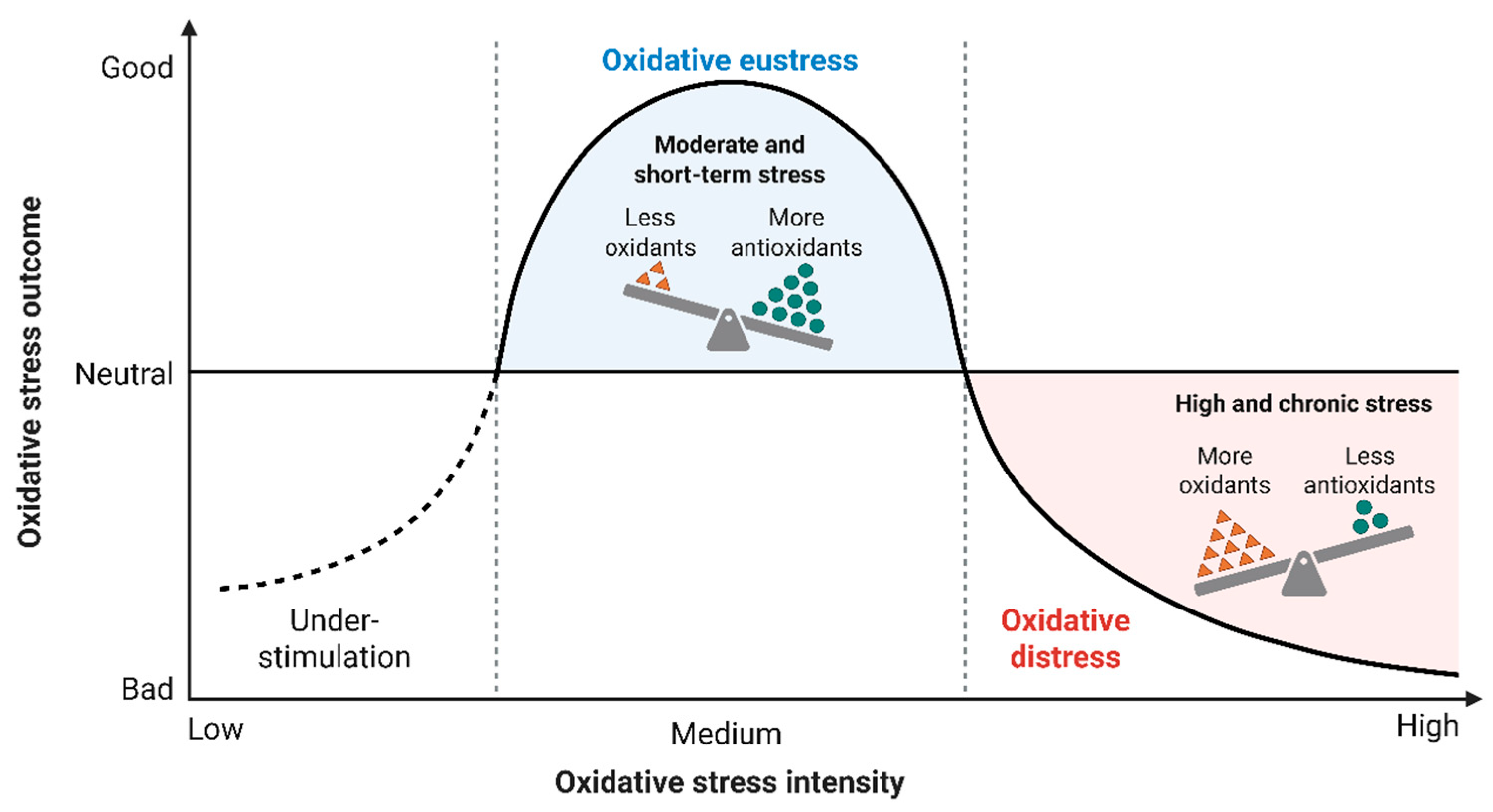

2. Oxidative Stress Pathways in Cardiovascular Disease

2.1. Sources of ROS in Cardiovascular Cells

2.1.1. NADPH Oxidases (NOX)

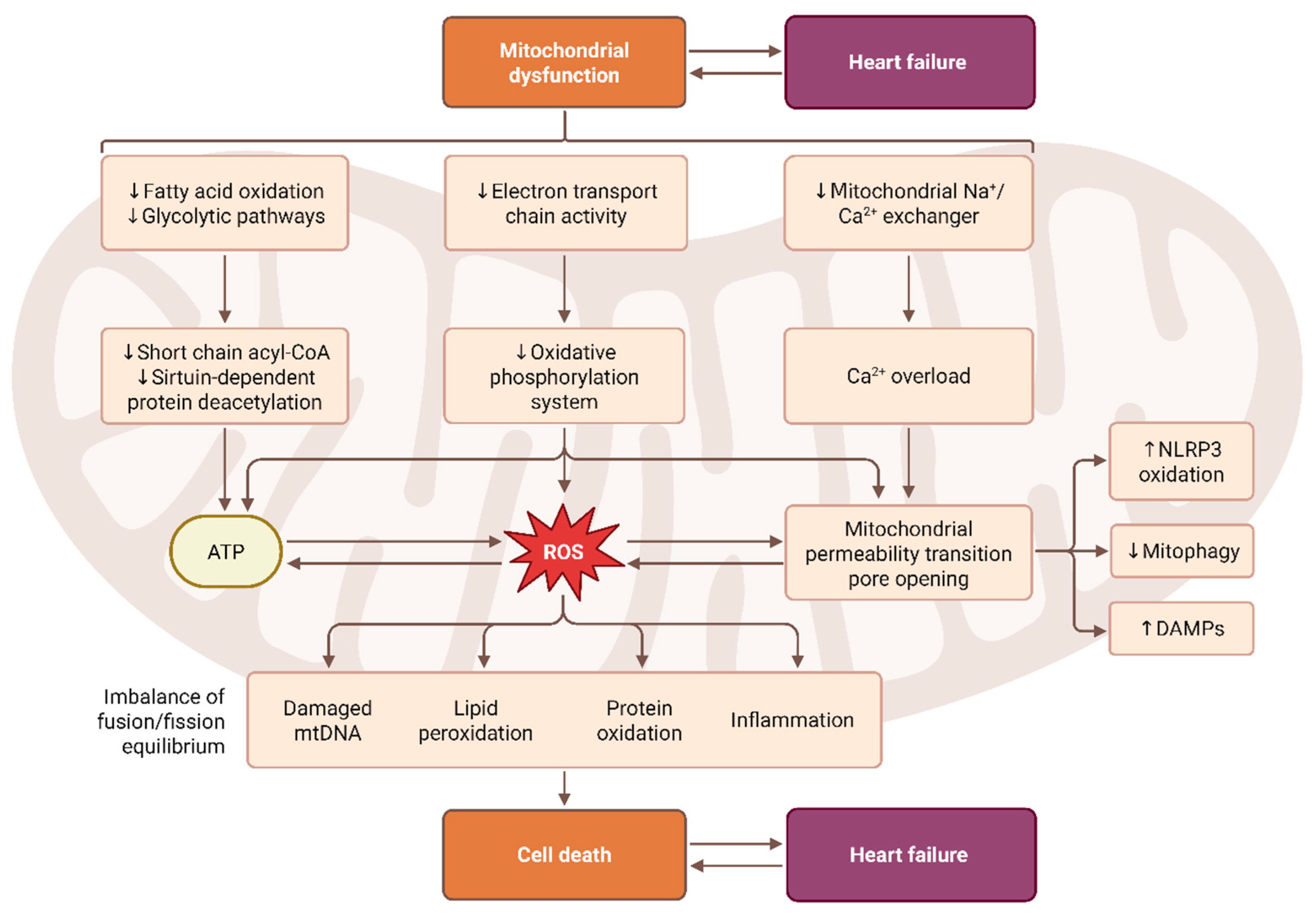

2.1.2. Mitochondrial ROS

2.1.3. Uncoupled eNOS

2.1.4. Xanthine Oxidase and Myeloperoxidas

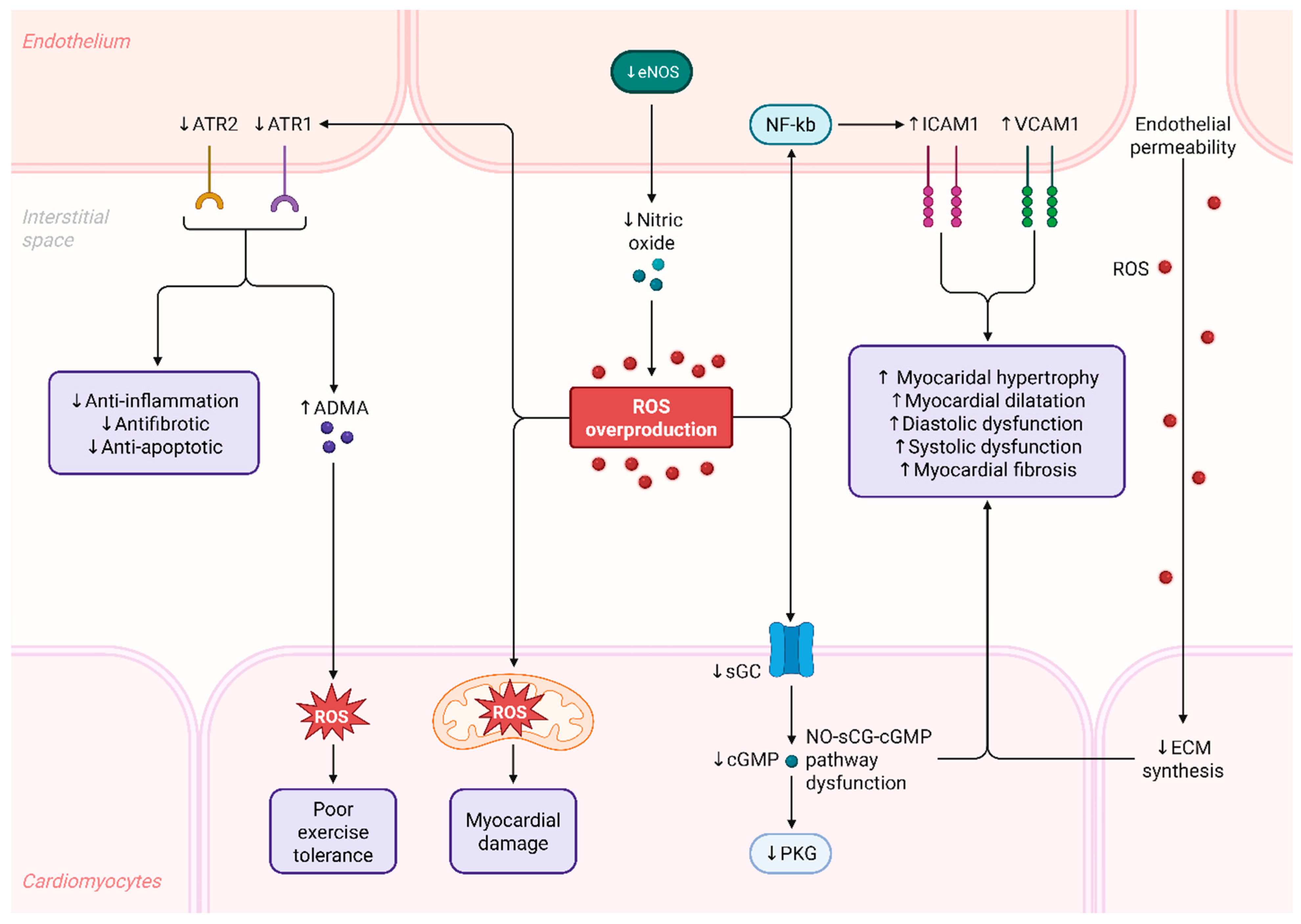

2.2. Mechanistic Consequences of Redox Imbalance

2.3. Role of Endothelial Dysfunction in Heart Failure

2.4. Vitamin E

2.5. Vitamin C

2.6. β-Carotene

2.7. Polyphenols

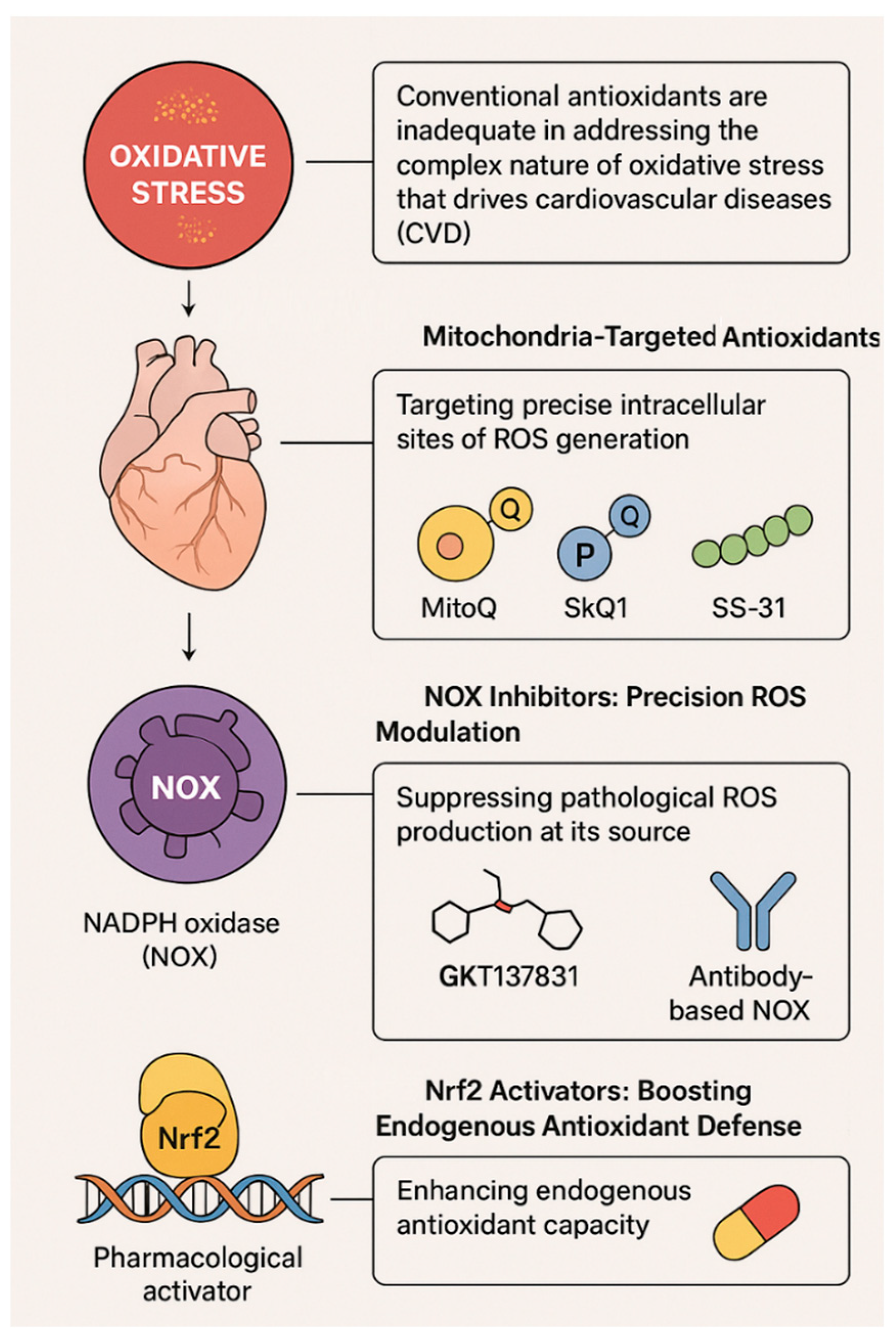

3. Next-Generation Antioxidant Therapies

3.1. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants

3.1.1. MitoQ

3.1.2. SkQ1 (Plastoquinonyl-Decyltriphenylphosphonium)

3.1.3. SS-31 (Elamipretide)

3.2. NOX Inhibitors: Fine-Tuning ROS Production

3.2.1. GKT137831 (Setanaxib)

3.2.2. Peptide and Antibody-Based NOX Inhibitors

3.3. Nrf2 Activators: Boosting Endogenous Antioxidant Defense

4. Clinical Evidence and Translational Progress of Next-Generation Antioxidants

4.1. MitoQ Clinical Trials

4.2. Elamipretide Trials

4.3. Setanaxib Trials

4.4. Findings on the Function and Potential Applications of Nrf2 Activators

4.5. Nanomedicine Evaluation Trials

5. Integration of Antioxidants into the Cardiovascular Therapeutic Framework

5.1. Combining Antioxidants with Standard Cardiovascular Therapies

5.2. Integration of Antioxidants Using Precision Medicine Tools

6. Clinical Trials on Next-Generation Antioxidants in Cardiovascular Disease

7. Challenges and Future Directions

8. Limitations of the Study

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Cesare, M.; Perel, P.; Taylor, S.; Kabudula, C.; Bixby, H.; Gaziano, T.A.; McGhie, D.V.; Mwangi, J.; Pervan, B.; Narula, J.; et al. The Heart of the World. Glob. Heart 2024, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahtafti, P.; Soleimani, H.; Khanmohammadi, S.; Habibzadeh, A.; Taebi, M.; Azarboo, A.; Shirinezhad, A.; Valinejad, A.; Blaha, M.J.; Al-Kindi, S.; et al. Global trends in cardiovascular mortality attributable to high body mass index: 1990–2021 analysis with future projections. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, 24, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, U.C.; Bhol, N.K.; Swain, S.K.; Samal, R.R.; Nayak, P.K.; Raina, V.; Panda, S.K.; Kerry, R.G.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Neurological Disorders: Mechanisms and Implications. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Alkhathami, A.G.; Al-Keridis, L.; Alshammari, N.; Al-Amrah, H.; Farooqui, A.; Yadav, D.K. Integrative machine learning and molecular simulation strategies for BCR-ABL inhibition in chronic myeloid leukemia. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2025, 37, 7792025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardahanlı, İ.; Aslan, R.; Arıkan, E.; Özel, F.; Özmen, M.; Akgün, O.; Akdoğan, M.; Özkan, H.İ. Redox Imbalance and Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases: Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targets. Arch. Med. Sci. Atheroscler. Dis. 2025, 10, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.D.; Praveen, A.; Yadav, D.K. Role of PARP in TNBC: Mechanism of Inhibition, Clinical Applications, and Resistance. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madamanchi, N.R.; Runge, M.S. Redox Signaling in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 61, 473–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.D.; Yadav, D.K. TNBC: Potential Targeting of Multiple Receptors for a Therapeutic Breakthrough, Nanomedicine and Immunotherapy. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.D.; Yadav, D.K.; Shin, D. Circular RNA-based liquid biopsy: A promising approach for monitoring drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2025, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Shamsi, A.; Shahwan, M.; Khuzin, D.; Yadav, D.K. Targeting programmed death ligand 1 for anticancer therapy using computational drug repurposing and molecular simulations. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.D.; Yadav, D.K.; Shin, D. Targeting the CXCR4/CXCL12 Axis to Overcome Drug Resistance in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cells 2025, 14, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.D.; Yadav, D.K.; Shin, D. Non-coding RNAs in cancer therapy-induced cardiotoxicity: Unlocking precision biomarkers for early detection. Cell Signal. 2025, 135, 111982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Tian, H.-X.; Rong, D.-C.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Zeng, J.; Xu, H.; Mei, J.; Wang, L.-Y.; Liou, Y.-L.; et al. ROS Homeostasis in Cell Fate, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutic Interventions. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Bermejo, R.; Hernández-Hernández, A. The Importance of NADPH Oxidases and Redox Signaling in Angiogenesis. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Vascular Noxs, and Hypertension: Focus on Translational and Clinical Research. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panth, N.; Paudel, K.R.; Parajuli, K. Reactive Oxygen Species: A Key Hallmark of Cardiovascular Disease. Adv. Med. 2016, 2016, 9152732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, A.; Viviano, M.; Feoli, A.; Milite, C.; Sarno, G.; Castellano, S.; Sbardella, G. NADPH Oxidases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Current Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 11632–11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, J. Deciphering Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Disease Progression: A Blueprint for Mechanistic Understanding and Therapeutic Innovation. Antioxidants 2024, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirichen, H.; Yaigoub, H.; Xu, W.; Wu, C.; Li, R.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Contribution in Chronic Kidney Disease Progression Through Oxidative Stress. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 627837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez De La Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugger, H.; Pfeil, K. Mitochondrial ROS in Myocardial Ischemia Reperfusion and Remodeling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Shi, H.; Li, F.; Duan, Y.; Guo, Q. New Insights into the Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Oxidative Stress-Induced Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, A.R.; Huckaby, L.V.; Shiva, S.S.; Zuckerbraun, B.S. Nitric Oxide and Endothelial Dysfunction. Crit. Care Clin. 2020, 36, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaar, M.C.; Westerweel, P.E.; Van Zonneveld, A.J.; Rabelink, T.J. Free Radical Production by Dysfunctional eNOS. Heart 2004, 90, 494–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Förstermann, U.; Xia, N.; Kuntic, M.; Münzel, T.; Daiber, A. Pharmacological Targeting of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Dysfunction and Nitric Oxide Replacement Therapy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 237, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, E.E.; Khoo, N.K.H.; Hundley, N.J.; Malik, U.Z.; Freeman, B.A.; Tarpey, M.M. Hydrogen Peroxide Is the Major Oxidant Product of Xanthine Oxidase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, C. The Roles of Neutrophil-Derived Myeloperoxidase (MPO) in Diseases: The New Progress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, C.M.; Leandro, A.; Azul, L.; Seiça, R.; Perry, G. Vascular Oxidative Stress: Impact and Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scioli, M.G.; Storti, G.; D’Amico, F.; Rodríguez Guzmán, R.; Centofanti, F.; Doldo, E.; Céspedes Miranda, E.M.; Orlandi, A. Oxidative Stress and New Pathogenetic Mechanisms in Endothelial Dysfunction: Potential Diagnostic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Riva, P.; Marta-Enguita, J.; Rodríguez-Antigüedad, J.; Bergareche, A.; De Munain, A.L. Understanding Endothelial Dysfunction and Its Role in Ischemic Stroke After the Outbreak of Recanalization Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, R.R.; Prasad, A.; Pospíšil, P.; Kzhyshkowska, J. ROS Signaling in Innate Immunity via Oxidative Protein Modifications. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1359600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, N.; Jeltema, D.; Duan, Y.; He, Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: An Overview of Mechanisms of Activation and Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Yang, Y. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Vascular Remodeling in Hypertension. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiolino, G.; Rossitto, G.; Caielli, P.; Bisogni, V.; Rossi, G.P.; Calò, L.A. The Role of Oxidized Low-Density Lipoproteins in Atherosclerosis: The Myths and the Facts. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 714653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drera, A.; Rodella, L.; Brangi, E.; Riccardi, M.; Vizzardi, E. Endothelial Dysfunction in Heart Failure: What Is Its Role? J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuer, D.S.; Handberg, E.M.; Mehrad, B.; Wei, J.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Pepine, C.J.; Keeley, E.C. Microvascular Dysfunction as a Systemic Disease: A Review of the Evidence. Am. J. Med. 2022, 135, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannitsi, S.; Maria, B.; Bechlioulis, A.; Naka, K. Endothelial Dysfunction and Heart Failure: A Review of the Existing Bibliography with Emphasis on Flow Mediated Dilation. JRSM Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019, 8, 2048004019843047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arauna, D.; Navarrete, S.; Albala, C.; Wehinger, S.; Pizarro-Mena, R.; Palomo, I.; Fuentes, E. Understanding the Role of Oxidative Stress in Platelet Alterations and Thrombosis Risk among Frail Older Adults. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, K.; Kim, K.; Sakaki, J.R.; Chun, O.K. Relative Validity of Dietary Total Antioxidant Capacity for Predicting All-Cause Mortality in Comparison to Diet Quality Indexes in US Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, J.A. Antioxidants and Coronary Artery Disease: From Pathophysiology to Preventive Therapy. Coron. Artery Dis. 2015, 26, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, G.R.; Benjamin, I.J. Antioxidants in Cardiovascular Health: Implications for Disease Modeling Using Cardiac Organoids. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlFayi, M.S.; Saeed, M.; Ahmad, I.; Kausar, M.A.; Siddiqui, S.; Irem, S.; Alshammari, F.F.; Badraoui, R.; Yadav, D.K. Unveiling the therapeutic role of penfluridol and BMS-754,807: NUDT5 inhibition in breast cancer. Chem. Phys. Impact 2025, 10, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Saeed, M.U.; Choudhury, A.; Mohammad, T.; Hussain, A.; AlAjmi, M.F.; Yadav, D.K.; Hassan, M.I. Therapeutic Targeting of Interleukin-2-Inducible T-Cell Kinase (ITK) for Cancer and Immunological Disorders: Potential Next-Generation ITK Inhibitors. OMICS 2025, 29, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananta; Shah, C.; Pal, D.; Althagafi, I.; Pratap, R.; Yadav, D.K.; Kumar, S. Design, Synthesis, and Simulation of Functionalized 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroisoquinolines to Treat Acute Leukemia Cells. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202404024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, A.D.; Thomassen, A.S.; Mashaw, S.A.; MacDonald, E.M.; Waguespack, A.; Hickey, L.; Singh, A.; Gungor, D.; Kallurkar, A.; Kaye, A.M.; et al. Vitamin E (α-Tocopherol): Emerging Clinical Role and Adverse Risks of Supplementation in Adults. Cureus 2025, 17, e78679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, A.; Moldoveanu, E.-T.; Niculescu, A.-G.; Grumezescu, A.M. Vitamin C: A Comprehensive Review of Its Role in Health, Disease Prevention, and Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2025, 30, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykkesfeldt, J. On the Effect of Vitamin C Intake on Human Health: How to (Mis)Interprete the Clinical Evidence. Redox Biol. 2020, 34, 101532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, S.; Càrcamo, J.M.; Golde, D.W. Vitamin C Enters Mitochondria via Facilitative Glucose Transporter 1 (Gluti) and Confers Mitochondrial Protection against Oxidative Injury. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Yi, Y.; Ji, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, H. The Dual Role of Vitamin C in Cancer: From Antioxidant Prevention to Prooxidant Therapeutic Applications. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1633447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.R. A Randomized Factorial Trial of Vitamins C and E and Beta Carotene in the Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Women: Results from the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Na, X.; Zhao, A. β-Carotene Supplementation and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middha, P.; Weinstein, S.J.; Männistö, S.; Albanes, D.; Mondul, A.M. β-Carotene Supplementation and Lung Cancer Incidence in the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study: The Role of Tar and Nicotine. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Morales, A.; Medina-García, M.; Martínez-Peinado, P.; Pascual-García, S.; Pujalte-Satorre, C.; López-Jaén, A.B.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M.; Sempere-Ortells, J.M. The Antitumour Mechanisms of Carotenoids: A Comprehensive Review. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón-Ramírez, A.-L.; Maldonado-Vega, M.; Quintanar-Escorza, M.-A.; Hernández, G.; Arévalo-Rivas, B.-I.; Zentella-Dehesa, A.; Calderón-Salinas, J.-V. Effect of Vitamin E and C Supplementation on Oxidative Damage and Total Antioxidant Capacity in Lead-Exposed Workers. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2014, 37, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, H.; Passarelli, S.; Szeto, J.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The Role of Polyphenols in Human Health and Food Systems: A Mini-Review. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pietro, N.; Baldassarre, M.P.A.; Cichelli, A.; Pandolfi, A.; Formoso, G.; Pipino, C. Role of Polyphenols and Carotenoids in Endothelial Dysfunction: An Overview from Classic to Innovative Biomarkers. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 6381380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatif, M. Current Understanding of Polyphenols to Enhance Bioavailability for Better Therapies. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da C. Pinaffi-Langley, A.C.; Tarantini, S.; Hord, N.G.; Yabluchanskiy, A. Polyphenol-Derived Microbiota Metabolites and Cardiovascular Health: A Concise Review of Human Studies. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccellino, M.; D’Angelo, S. Anti-Obesity Effects of Polyphenol Intake: Current Status and Future Possibilities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Sidor, A.; O’Rourke, B. Compartment-Specific Control of Reactive Oxygen Species Scavenging by Antioxidant Pathway Enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 11185–11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Gubory, K.H. Mitochondria: Omega-3 in the Route of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44, 1569–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Deng, F.; Deng, Z. Oxidative Stress: Signaling Pathways, Biological Functions, and Disease. MedComm 2025, 6, e70268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, A.G.; Graziano, R.; Nicolantonio, D. Carotenoids: Potential Allies of Cardiovascular Health? Food Nutr. Res. 2015, 59, 26762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, C.; Keshavamurthy, S.; Saha, S. Nutraceuticals in the management of cardiovascular risk factors: Where is the evidence? Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 21, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moris, D.; Spartalis, M.; Spartalis, E.; Karachaliou, G.-S.; Karaolanis, G.I.; Tsourouflis, G.; Tsilimigras, D.I.; Tzatzaki, E.; Theocharis, S. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Diseases and the Clinical Significance of Myocardial Redox. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahar, N.; Sohag, M.S.U. Advancements in Mitochondrial-Targeted Antioxidants: Organelle-Specific Drug Delivery for Disease Management. Adv. Redox Res. 2025, 17, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Fang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.-X.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Zhang, K. Mitochondria-Targeted Nanocarriers Promote Highly Efficient Cancer Therapy: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 784602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.; Sack, M. Targeting the Mitochondria to Augment Myocardial Protection. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2008, 8, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, L.; Gao, M.; Dai, M.; Zheng, Y.; Qu, L.; Zhang, J.; Gong, G. A Comparative Study of the Efficiency of Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants MitoTEMPO and SKQ1 under Oxidative Stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 224, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadov, S.; Jang, S.; Parodi-Rullán, R.; Khuchua, Z.; Kuznetsov, A.V. Mitochondrial Permeability Transition in Cardiac Ischemia–Reperfusion: Whether Cyclophilin D Is a Viable Target for Cardioprotection? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 2795–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, W.; Tamucci, J.D.; Ng, E.L.; Liu, S.; Birk, A.V.; Szeto, H.H.; May, E.R.; Alexandrescu, A.T.; Alder, N.N. Structure-Activity Relationships of Mitochondria-Targeted Tetrapeptide Pharmacological Compounds. eLife 2022, 11, e75531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillard, M.; Abdellatif, M.; Andreadou, I.; Bär, C.; Bertrand, L.; Brundel, B.J.J.M.; Chiva-Blanch, G.; Davidson, S.M.; Dawson, D.; Di Lisa, F.; et al. Mitochondrial Targets in Ischaemic Heart Disease and Heart Failure, and Their Potential for a More Efficient Clinical Translation: A Scientific Statement of the ESC Working Group on Cellular Biology of the Heart and the ESC Working Group on Myocardial Function. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2025, 27, 1720–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadis, S.; Papanikolaou, N.A. Reactive Oxygen Species Mechanisms that Regulate Protein–Protein Interactions in Can-cer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Almeida, A.J.P.O.; De Oliveira, J.C.P.L.; Da Silva Pontes, L.V.; De Souza Júnior, J.F.; Gonçalves, T.A.F.; Dantas, S.H.; De Almeida Feitosa, M.S.; Silva, A.O.; De Medeiros, I.A. ROS: Basic Concepts, Sources, Cellular Signaling, and Its Implications in Aging Pathways. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1225578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Murugesan, P.; Huang, K.; Cai, H. NADPH Oxidases and Oxidase Crosstalk in Cardiovascular Diseases: Novel Therapeutic Targets. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, C.G.; Oteiza, P.I.; Hid, E.J.; Galleano, M. (Poly)Phenols and the Regulation of NADPH Oxidases. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Pagano, E.; Pagano, P.J. Rational Design and Delivery of NOX-Inhibitory Peptides. In NADPH Oxidases; Knaus, U.G., Leto, T.L., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 1982, pp. 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- Hissa, M.R.N.; Cavalcante, L.L.A.; Guimarães, S.B.; Hissa, M.N. A 16-Week Study to Compare the Effect of Vildagliptin versus Gliclazide on Postprandial Lipoprotein Concentrations and Oxidative Stress in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Inadequately Controlled with Metformin Monotherapy. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2015, 7, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labbé, P.; Thorin, E.; Thorin-Trescases, N. The Dual Role of NOX4 in Cardiovascular Diseases: Driver of Oxidative Stress and Mediator of Adaptive Remodeling. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrov, A.E.; Vendrov, K.C.; Smith, A.; Yuan, J.; Sumida, A.; Robidoux, J.; Runge, M.S.; Madamanchi, N.R. NOX4 NADPH Oxidase-Dependent Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Aging-Associated Cardiovascular Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 1389–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.; Lai, Z.; Huang, G.; Lin, J.; Huang, W.; Qin, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hu, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Jiang, L.; et al. Setanaxib Mitigates Oxidative Damage Following Retinal Ischemia-Reperfusion via NOX1 and NOX4 Inhibition in Retinal Ganglion Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 170, 116042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, P.; Carbone, M.; Jones, D.; Levy, C.; Little, N.; Wiesel, P.; Nevens, F.; the study investigators. Setanaxib, a First-in-class Selective NADPH Oxidase 1/4 Inhibitor for Primary Biliary Cholangitis: A Randomized, Placebo-controlled, Phase 2 Trial. Liver Int. 2023, 43, 1507–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augsburger, F.; Filippova, A.; Rasti, D.; Seredenina, T.; Lam, M.; Maghzal, G.; Mahiout, Z.; Jansen-Dürr, P.; Knaus, U.G.; Doroshow, J.; et al. Pharmacological characterization of the seven human NOX isoforms and their inhibitors. Redox Biol. 2019, 26, 101272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, M.E.; Sureshkumar, S.; Carrera Espinoza, M.J.; Hakim, N.L.; Espitia, C.M.; Bi, F.; Kelly, K.R.; Wang, W.; Nawrocki, S.T.; Carew, J.S. P47phox: A Central Regulator of NADPH Oxidase Function and a Promising Therapeutic Target in Redox-Related Diseases. Cells 2025, 14, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antony, S.; Wu, Y.; Hewitt, S.M.; Anver, M.R.; Butcher, D.; Jiang, G.; Meitzler, J.L.; Liu, H.; Juhasz, A.; Lu, J.; et al. Characterization of NADPH Oxidase 5 Expression in Human Tumors and Tumor Cell Lines with a Novel Mouse Monoclonal Antibody. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plichta, J.; Kuna, P.; Panek, M. Biologic Drugs in the Treatment of Chronic Inflammatory Pulmonary Diseases: Recent Developments and Future Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1207641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Huang, W.; Wu, X.; Xia, H. Advances in Techniques for the Structure and Functional Optimization of Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Deruy, E.; Peugnet, V.; Turkieh, A.; Pinet, F. Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vomhof-DeKrey, E.E.; Picklo, M.J. The Nrf2-Antioxidant Response Element Pathway: A Target for Regulating Energy Metabolism. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1201–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, B.; Jiang, T.; Wu, T.; Tao, S.; De La Vega, M.R.; Tian, W.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. Molecular Mechanisms of Nrf2 Regulation and How These Influence Chemical Modulation for Disease Intervention. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2015, 43, 680–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wu, M.; Zeng, L.; Wang, D. The Beneficial Role of Nrf2 in the Endothelial Dysfunction of Atherosclerosis. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2022, 2022, 4287711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintrich, J.; Kindermann, I.; Ukena, C.; Selejan, S.; Werner, C.; Maack, C.; Laufs, U.; Tschöpe, C.; Anker, S.D.; Lam, C.S.P.; et al. Therapeutic Approaches in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Past, Present, and Future. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020, 109, 1079–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, J.D.; Tang, X.; Campbell, M.D.; Reyes, G.; Kramer, P.A.; Stuppard, R.; Keller, A.; Zhang, H.; Rabinovitch, P.S.; Marcinek, D.J.; et al. Mitochondrial Protein Interaction Landscape of SS-31. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 15363–15373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.O.; Berryman-Maciel, M.; Darvish, S.; Coppock, M.E.; You, Z.; Chonchol, M.; Seals, D.R.; Rossman, M.J. Mitochondrial-Targeted Antioxidant Supplementation for Improving Age-Related Vascular Dysfunction in Humans: A Study Protocol. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 980783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A.V.; Chelombitko, M.A.; Chernyavskij, D.A.; Galkin, I.I.; Pletjushkina, O.Y.; Vasilieva, T.V.; Zinovkin, R.A.; Chernyak, B.V. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant SkQ1 Prevents the Development of Experimental Colitis in Mice and Impairment of the Barrier Function of the Intestinal Epithelium. Cells 2022, 11, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.; Zheng, D.; He, J.; Xiong, S.; Xu, J.; Hou, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction as a Therapeutic Nexus in HFpEF: Therapeutic Target and Pharmacological Advances. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1676988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kang, W.; Yang, S.; Park, S.H.; Ha, S.Y.; Paik, Y.H. NADPH oxidase 4 deficiency promotes hepatocellular carcinoma arising from hepatic fibrosis by inducing M2-macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, B.A.; Smith, S.M.E.; Li, Y.; Lambeth, J.D. NOX2 As a Target for Drug Development: Indications, Possible Complications, and Progress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 375–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, A.; Solas, M.; Pejenaute, Á.; Abellanas, M.A.; Garcia-Lacarte, M.; Aymerich, M.S.; Marqués, J.; Ramírez, M.J.; Zalba, G. Expression of Endothelial NOX5 Alters the Integrity of the Blood-Brain Barrier and Causes Loss of Memory in Aging Mice. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Ahmed, D.; Ahmad, N.; Qamar, M.T.; Alruwaili, N.K.; Bukhari, S.N.A. Extraction and Characterization of Microcrystalline Cellulose from Lagenaria siceraria Fruit Pedicles. Polymers 2022, 14, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.M.; Holt, A.G. Why Antioxidant Therapies Have Failed in Clinical Trials. J. Theor. Biol. 2018, 457, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalinia, M.; Weiskirchen, R. Advances in Personalized Medicine: Translating Genomic Insights into Targeted Therapies for Cancer Treatment. Ann. Transl. Med. 2025, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, W. Clinical Research Progress of Small Molecule Compounds Targeting Nrf2 for Treating Inflammation-Related Diseases. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casin, K.M.; Calvert, J.W. Harnessing the Benefits of Endogenous Hydrogen Sulfide to Reduce Cardiovascular Disease. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscianz, E.; Tesser, A.; Rimondi, E.; Melloni, E.; Celeghini, C.; Marcuzzi, A. MitoQ Is Able to Modulate Apoptosis and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Battson, M.L.; Cuevas, L.M.; Eng, J.S.; Murphy, M.P.; Seals, D.R. Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant Therapy with MitoQ Ameliorates Aortic Stiffening in Old Mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2018, 124, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismaiel, A.; Dumitrascu, D.L. How to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Am. J. Ther. 2023, 30, e242–e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannito, S.; Giardino, I.; d’Apolito, M.; Pettoello-Mantovani, M.; Scaltrito, F.; Mangieri, D.; Piscazzi, A. The Multifaceted Role of Mitochondria in Angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, C.; Varzideh, F.; Farroni, E.; Mone, P.; Kansakar, U.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Santulli, G. Elamipretide: A Review of Its Structure, Mechanism of Action, and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daubert, M.A.; Yow, E.; Dunn, G.; Marchev, S.; Barnhart, H.; Douglas, P.S.; O’Connor, C.; Goldstein, S.; Udelson, J.E.; Sabbah, H.N. Novel Mitochondria-Targeting Peptide in Heart Failure Treatment: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Elamipretide. Circ. Heart Fail. 2017, 10, e004389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajner, M.; Amaral, A.U. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Fatty Acid Oxidation Disorders: Insights from Human and Animal Studies. Biosci. Rep. 2016, 36, e00281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, T.; Khalid, S.N.; Bilal, M.I.; Ijaz, S.H.; Fudim, M.; Greene, S.J.; Warraich, H.J.; Nambi, V.; Virani, S.S.; Fonarow, G.C.; et al. Ongoing and Future Clinical Trials of Pharmacotherapy for Heart Failure. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2024, 24, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbah, H.N. Elamipretide for Barth Syndrome Cardiomyopathy: Gradual Rebuilding of a Failed Power Grid. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27, 1911–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Paik, Y.H.; Watanabe, S.; Laleu, B.; Gaggini, F.; Fioraso-Cartier, L.; Molango, S.; Heitz, F.; Merlot, C.; Szyndralewiez, C.; et al. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase in experimental liver fibrosis: GKT137831 as a novel potential therapeutic agent. Hepatology 2012, 56, 2316–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shimizu, H.; Siu, K.L.; Mahajan, A.; Chen, J.N.; Cai, H. NADPH oxidase 4 induces cardiac arrhythmic phenotype in zebrafish. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 23200–23208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burtenshaw, D.; Hakimjavadi, R.; Redmond, E.; Cahill, P. Nox, Reactive Oxygen Species and Regulation of Vascular Cell Fate. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checa, J.; Aran, J.M. Reactive Oxygen Species: Drivers of Physiological and Pathological Processes. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 13, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermot, A.; Petit-Härtlein, I.; Smith, S.M.E.; Fieschi, F. NADPH Oxidases (NOX): An Overview from Discovery, Molecular Mechanisms to Physiology and Pathology. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledinos-Antón, N.; Fernández-Ginés, R.; Manda, G.; Cuadrado, A. Activators and Inhibitors of NRF2: A Review of Their Potential for Clinical Development. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9372182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.K.; Singh, D.D.; Shin, D. Distinctive roles of aquaporins and novel therapeutic opportunities against cancer. RSC Med. Chem. 2024, 16, 640–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.D.; Haque, S.; Kim, Y.; Han, I.; Yadav, D.K. Remodeling of tumour microenvironment: Strategies to overcome therapeutic resistance and innovate immunoengineering in triple-negative breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1455211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, A.; Altwaijry, N.; Shahwan, M.; Ashames, A.; Yadav, D.K.; Furkan, M.; Khan, R.H. Identification of potential inhibitors of Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 21 from repurposed drugs: Implications in anticancer therapeutics. Chem. Phys. Impact 2025, 10, 100792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Khan, M.S.; Mathur, Y.; Sulaimani, M.N.; Farooqui, N.; Ahmad, S.F.; Nadeem, A.; Yadav, D.K.; Mohammad, T. Structure-based identification of potential inhibitors of ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1, targeting cancer therapy: A combined docking and molecular dynamics simulations approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 42, 5758–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, J. Antioxidative Nanomaterials and Biomedical Applications. Nano Today 2019, 27, 146–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.D.; Lee, H.-J.; Yadav, D.K. Recent Clinical Advances on Long Non-Coding RNAs in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cells 2023, 12, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, F.; Jiang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Ou, M.; Mei, L.; Wang, Q. Mitochondrial-Targeted and ROS-Responsive Nanocarrier via Nose-to-Brain Pathway for Ischemic Stroke Treatment. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 5107–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, H.; Umar, A.; Nusrat, N.; Mansour, M.; Ullah, A.; Honey, S.; Sohail, M.J.; Abbas, M.; Aslam, M.W.; Khan, M.U. Nanomaterials in the Treatment of Degenerative Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Explor. BioMat-X 2024, 1, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Tiwari, R.K.; Saeed, M.; Al-Amrah, H.; Han, I.; Choi, E.-H.; Yadav, D.K.; Ansari, I.A. Carvacrol instigates intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis with abrogation of cell cycle progression in cervical cancer cells: Inhibition of Hedgehog/GLI signaling cascade. Front. Chem. 2023, 10, 1064191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatfield, K.C.; Sparagna, G.C.; Chau, S.; Phillips, E.K.; Ambardekar, A.V.; Aftab, M.; Mitchell, M.B.; Sucharov, C.C.; Miyamoto, S.D.; Stauffer, B.L. Elamipretide Improves Mitochondrial Function in the Failing Human Heart. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2019, 4, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruqui, T.; Khan, M.S.; Akhter, Y.; Khan, S.; Rafi, Z.; Saeed, M.; Han, I.; Choi, E.-H.; Yadav, D.K. RAGE Inhibitors for Targeted Therapy of Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.M.; Lees, J.G.; Murray, A.J.; Velagic, A.; Lim, S.Y.; De Blasio, M.J.; Ritchie, R.H. Precision Medicine. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2025, 10, 101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Gong, X.; Li, J.; Wen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z. Current Approaches of Nanomedicines in the Market and Various Stage of Clinical Translation. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 3028–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Kang, P.M. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Treatments in Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, M.; Izadi, Z.; Jafari, S.; Casals, E.; Rezaei, F.; Aliabadi, A.; Moore, A.; Ansari, A.; Puntes, V.; Jaymand, M.; et al. Preclinical Studies Conducted on Nanozyme Antioxidants: Shortcomings and Challenges Based on US FDA Regulations. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 1133–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.C.; Sharma, A.; Prasad, S.; Singh, K.; Kumar, M.; Sherawat, K.; Tuli, H.S.; Gupta, M. Novel Therapeutic Agents in Clinical Trials: Emerging Approaches in Cancer Therapy. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.K.; Laufs, U. Pleiotropic Effects of Statins. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 45, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorriento, D.; De Luca, N.; Trimarco, B.; Iaccarino, G. The Antioxidant Therapy: New Insights in the Treatment of Hypertension. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veshohilova, T.P. Effect of combined use of steroid preparations with pyrroxane on the gonadotropic function of the hypophysis. Akush. Ginekol. 1975, 10, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Farnaghi, S.; Prasadam, I.; Cai, G.; Friis, T.; Du, Z.; Crawford, R.; Mao, X.; Xiao, Y. Protective Effects of Mitochondria-targeted Antioxidants and Statins on Cholesterolinduced Osteoarthritis. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Yu, X.; Guan, Q.; Shen, Y.; Liao, J.; Liu, Y.; Su, Z. Cholesterol Metabolism: Molecular Mechanisms, Biological Functions, Diseases, and Therapeutic Targets. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed Saleem, T. ACE Inhibitors—Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists: A Useful Combination Therapy for Ischemic Heart Disease. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2010, 2, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Xu, N.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Xiao, J.; Ji, X. Setanaxib (GKT137831) Ameliorates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Inhibiting the NOX1/NOX4/Reactive Oxygen Species/MAPK Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 823975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Luo, X.; Liao, B.; Li, G.; Feng, J. Insights into SGLT2 Inhibitor Treatment of Diabetic Cardiomyopathy: Focus on the Mechanisms. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLachlan, J.; Beattie, E.; Murphy, M.P.; Koh-Tan, C.H.H.; Olson, E.; Beattie, W.; Dominiczak, A.F.; Nicklin, S.A.; Graham, D. Combined Therapeutic Benefit of Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant, MitoQ10, and Angiotensin Receptor Blocker, Losartan, on Cardiovascular Function. J. Hypertens. 2014, 32, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.V.; Javadov, S.; Sommer, N. Cellular ROS and Antioxidants: Physiological and Pathological Role. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, A.; Zhou, J.; Chen, W.; Kou, Y. Effectiveness of Different Therapeutic Measures Combined with Aerobic Exercise as an Intervention in Patients with Depression: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1573557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, D.; Wu, Q.; Yu, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Liu, S. The Role of Multi-Omics in Biomarker Discovery, Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Monitoring of Tissue Repair and Regeneration Processes. J. Orthop. Transl. 2025, 54, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartaya, A.; Maiocchi, S.; Bahnson, E.M. Nanotherapies for Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease: A Case for Antioxidant Targeted Delivery. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 2019, 7, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völzke, H.; Schmidt, C.O.; Baumeister, S.E.; Ittermann, T.; Fung, G.; Krafczyk-Korth, J.; Hoffmann, W.; Schwab, M.; Meyer Zu Schwabedissen, H.E.; Dörr, M.; et al. Personalized Cardiovascular Medicine: Concepts and Methodological Considerations. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drăgoi, C.M.; Diaconu, C.C.; Nicolae, A.C.; Dumitrescu, I.-B. Redox Homeostasis and Molecular Biomarkers in Precision Therapy for Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.-P.; Qin, B.-D.; Jiao, X.-D.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zang, Y.-S. New Clinical Trial Design in Precision Medicine: Discovery, Development and Direction. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van ‘T Erve, T.J.; Lih, F.B.; Kadiiska, M.B.; Deterding, L.J.; Eling, T.E.; Mason, R.P. Reinterpreting the Best Biomarker of Oxidative Stress: The 8-Iso-PGF2α/PGF2α Ratio Distinguishes Chemical from Enzymatic Lipid Peroxidation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 83, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingg, J.-M.; Vlad, A.; Ricciarelli, R. Oxidized LDLs as Signaling Molecules. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Alsahli, M.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Myeloperoxidase as an Active Disease Biomarker: Recent Biochemical and Pathological Perspectives. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, S.R.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.H.; Zou, J.; Cao, W.W.; Luo, J.N.; Gao, H.; Liu, P.Q. Upregulation of Nox4 promotes angiotensin II-induced epidermal growth factor receptor activation and subsequent cardiac hypertrophy by increasing ADAM17 expression. Can. J. Cardiol. 2013, 29, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.K.; Sakuma, I.; Shimada, K.; Hayashi, T.; Quon, M.J. Combining Potent Statin Therapy with Other Drugs to Optimize Simultaneous Cardiovascular and Metabolic Benefits While Minimizing Adverse Events. Korean Circ. J. 2017, 47, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; LaRocca, T.J.; Sindler, A.L.; Zigler, M.C.; Murphy, M.P.; Seals, D.R. Mitochondria-targeted Antioxidant (MitoQ) Ameliorates Age-related Arterial Endothelial Dysfunction in Mice. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 2549–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Tu, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhu, N.; Fang, W.; Yu, Q. MSCs enhances the protective effects of valsartan on attenuating the doxorubicin-induced myocardial injury via AngII/NOX/ROS/MAPK signaling pathway. Aging 2021, 13, 22556–22570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassalle, C.; Maltinti, M.; Sabatino, L. Targeting Oxidative Stress for Disease Prevention and Therapy: Where Do We Stand, and Where Do We Go from Here. Molecules 2020, 25, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-S.; Maron, B.A.; Loscalzo, J. Multiomics Network Medicine Approaches to Precision Medicine and Therapeutics in Cardiovascular Diseases. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, M.G.; Patella, B.; Ferraro, M.; Di Vincenzo, S.; Pinto, P.; Torino, C.; Vilasi, A.; Giuffrè, M.R.; Juska, V.B.; O’Riordan, A.; et al. Wearable Sensor for Real-Time Monitoring of Oxidative Stress in Simulated Exhaled Breath. Biosens. Bioelectron. X 2024, 18, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurul, F.; Turkmen, H.; Cetin, A.E.; Topkaya, S.N. Nanomedicine: How Nanomaterials Are Transforming Drug Delivery, Bio-Imaging, and Diagnosis. Next Nanotechnol. 2025, 7, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelakovic, G.; Nikolova, D.; Gluud, L.L.; Simonetti, R.G.; Gluud, C. Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases. JAMA 2007, 297, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhubl, S.R. Why have antioxidants failed in clinical trials? Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 101, S14–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Xia, N.; Li, H. Roles of vascular oxidative stress and nitric oxide in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Jiang, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y. Next-generation antioxidants in cardiovascular therapy: Mechanistic insights and clinical potential. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 238, 108242. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.P. Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006, 295, C849–C868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, I.; Russo, G.; Curcio, F.; Bulli, G.; Aran, L.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Cacciatore, F.; Bonaduce, D.; et al. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocker, R.; Keaney, J.F. Role of oxidative modifications in atherosclerosis. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 1381–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madamanchi, N.R.; Vendrov, A.; Runge, M.S. Oxidative stress and vascular disease. Circ. Res. 2005, 97, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.; Griendling, K.K.; Landmesser, U.; Hornig, B.; Drexler, H. Role of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, T.; Daiber, A.; Gori, T. More than just antioxidants: How to translate redox biology into cardiovascular therapy. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2441–2448. [Google Scholar]

- Davignon, J. Beneficial cardiovascular pleiotropic effects of statins. Circulation 2004, 109, III39–III43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, D.K.; Trinh, K.T.L. Emerging Biomarkers in Metabolomics: Advancements in Precision Health and Disease Diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstermann, U.; Sessa, W.C. Nitric oxide synthases: Regulation and function. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, A.I.; Dao, V.T.-V.; Daiber, A.; Maghzal, G.J.; Di Lisa, F.; Kaludercic, N.; Leach, S.; Cuadrado, A.; Jaquet, V.; Seredenina, T.; et al. Reactive Oxygen-Related Diseases: Therapeutic Targets and Emerging Clinical Indications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 1171–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive Oxygen Species in Inflammation and Tissue Injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1126–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, X.; Lu, T. Role of Mitochondria in Physiological Activities, Diseases, and Therapy. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, I.; Yehye, W.A.; Etxeberria, A.E.; Alhadi, A.A.; Dezfooli, S.M.; Julkapli, N.B.M.; Basirun, W.J.; Seyfoddin, A. Nanoantioxidants: Recent Trends in Antioxidant Delivery Applications. Antioxidants 2019, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.R.; Atiee, G.; Chapman, B.; Reynolds, L.; Sun, J.; Cameron, A.M.; Wesson, R.N.; Burdick, J.F.; Sun, Z. A Phase I, First-in-Human Study to Evaluate the Safety and Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of MRG-001 in Healthy Subjects. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, D.J.R. Nox5 and the Regulation of Cellular Function. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2443–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, M.A.; Shultz, L.D.; Greiner, D.L. Humanized Mouse Models to Study Human Diseases. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2010, 17, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van’T Erve, T.J.; Lih, F.B.; Jelsema, C.; Deterding, L.J.; Eling, T.E.; Mason, R.P.; Kadiiska, M.B. Reinterpreting the Best Biomarker of Oxidative Stress: The 8-Iso-Prostaglandin F2α/Prostaglandin F2α Ratio Shows Complex Origins of Lipid Peroxidation Biomarkers in Animal Models. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 95, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girach, A.; Audo, I.; Birch, D.G.; Huckfeldt, R.M.; Lam, B.L.; Leroy, B.P.; Michaelides, M.; Russell, S.R.; Sallum, J.M.F.; Stingl, K.; et al. RNA-Based Therapies in Inherited Retinal Diseases. Ophthalmol. Eye Dis. 2022, 14, 25158414221134602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, T.; Bosch, J.; Levitt, M.F.; Goldstein, M.H. Effect of Sodium Nitrate Loading on Electrolyte Transport by the Renal Tubule. Am. J. Physiol. 1975, 229, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Yue, H.; Lu, G.; Wang, W.; Deng, Y.; Ma, G.; Wei, W. Advances in Delivering Oxidative Modulators for Disease Therapy. Research 2022, 2022, 9897464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Chen, X.; Liao, C. AI-Driven Wearable Bioelectronics in Digital Healthcare. Biosensors 2025, 15, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.-J.; Wu, J.; Gong, L.-J.; Yang, H.-S.; Chen, H. Non-Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Anti-Inflammatory Therapy: Mechanistic Insights and Future Perspectives. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1490300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, J.L.; Satia, J.A.; da Costa, K.A.; Boysen, G.; Collins, L.B.; Morrow, J.D.; Milne, G.L.; Swenberg, J.A. Comparison of three oxidative stress biomarkers in a sample of healthy adults. Biomarkers 2009, 14, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimeji, I.Y.; Jabba, H.L.; Adeoye, S.W.; Okunade, A.L.; Oladipo, A.O.; Bello, K.A.; Adebayo, R.A.; Yusuf, M.K.; Abdullahi, U.H.; Mohammed, T.A. The cardiometabolic benefits of curcumin: A focus on endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness in metabolic syndrome. Clin. Phytosci. 2025, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.N. | Agent | Type | Mechanism | Key Evidence | Considerations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MitoQ | Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant | TPP+-driven mitochondrial uptake; reduces mito-ROS | Human trials: improved endothelial function, reduced arterial stiffness | Long-term CV benefit yet unconfirmed | [96] |

| 2 | SkQ1 | Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant | Plastoquinone-TPP+ conjugate; prevents cardiomyocyte apoptosis | Strong cardioprotection in I/R injury models | Clinical translation ongoing | [97] |

| 3 | SS-31 (Elamipretide) | Mitochondrial peptide | Binds/stabilizes cardiolipin; improves ETC efficiency | HFpEF & HFrEF early trials show benefit | Delivery optimization needed | [98] |

| 4 | GKT137831 (Setanaxib) | NOX1/NOX4 inhibitor | Suppresses fibro-inflammatory ROS pathways | Reduces oxidative stress and vascular fibrosis | Few CV-focused trials completed | [99] |

| 5 | NOX2-ds-tat peptide | Peptide NOX2 inhibitor | Blocks p47phox–NOX2 assembly | Specific suppression of NOX2 superoxide | Early-stage; delivery challenges | [100] |

| 6 | NOX5 antibodies | Antibody inhibitor | Neutralizes NOX5 activity (human-specific) | Strong rationale for endothelial ROS control | Preclinical; stability/delivery issues | [101] |

| 7 | Nrf2 activators | Endogenous antioxidant boosters | KEAP1 inhibition → activation of cytoprotective gene network | Improved endothelial function & mitochondrial resilience | Overactivation risk | [101] |

| S.N. | Therapeutic Class/Agent | Clinical Trial Evidence | Key Cardiovascular Effects | Stage of Clinical Translation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants | MitoQ: improved endothelial function and reduced arterial stiffness in older adults; reduced liver inflammation in NAFLD | Enhanced endothelial NO bioavailability; reduced mitochondrial ROS; potential reduction in vascular aging and cardiometabolic risk | Early- to mid-phase human trials; larger CVD outcome studies pending | [130] |

| 2 | Elamipretide (SS-31) | Improved left ventricular stroke volume; ongoing trials in mitochondrial myopathy and heart failure | Restores mitochondrial energetics; reduces ROS; improves cardiac contractility | Phase II–III trials ongoing | [131] |

| 3 | NOX Inhibitors (Setanaxib/GKT137831) | Reduced fibrosis biomarkers in renal and fibrotic diseases; CVD-focused trials planned | Isoform-specific ROS suppression; improved endothelial function; potential anti-atherosclerotic effect | Early translational stage; cardiovascular trials in planning | [132] |

| 4 | Nrf2 Activators | Bardoxolone methyl: mixed results; dimethyl fumarate shows vascular anti-inflammatory effects | Enhances endogenous antioxidant defenses; reduces oxidative stress | Early human trials; limited by off-target effects | [133] |

| 5 | Nanomedicine-Based Antioxidants | Liposomal or polymeric carriers tested for safety and biodistribution | Improved antioxidant stability, bioavailability, and targeting | Early clinical studies; preclinical efficacy robust | [134] |

| S.N. | Strategy/Approach | Mechanism/Rationale | Potential Benefits | Challenges/Considerations | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Combination with Standard Therapies | Statins, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, beta-blockers, SGLT2 inhibitors possess intrinsic antioxidant or redox-modulating effects; combining with targeted antioxidants may enhance efficacy | Synergistic reduction in oxidative stress; improved endothelial function; enhanced mitochondrial protection; reduced arterial stiffness | Requires careful dosing to avoid excessive ROS suppression; potential pharmacokinetic interactions | [158] |

| 2 | Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants with Statins or SGLT2i | MitoQ, SS-31, SkQ1 restore mitochondrial membrane potential and NO bioavailability | Improved vascular and cardiac function; reduced oxidative damage in aging and metabolic CVD | Long-term safety and large-scale clinical outcome data needed | [159] |

| 3 | NOX Inhibitors with RAAS Modulation | Setanaxib or peptide-based NOX inhibitors + ACE inhibitors/ARBs | Dual suppression of enzymatic ROS; reduced vascular fibrosis and endothelial dysfunction | Species differences in NOX isoforms; careful patient selection via biomarkers | [160] |

| 4 | Biomarker-Guided Precision Therapy | Use of 8-iso-PGF2α, OxLDL, MPO, NOX isoform profiling to tailor antioxidant therapy | Personalized therapy targeting specific oxidative pathways; improved efficacy; minimized off-target effects | Requires validated biomarkers; standardization across labs; cost considerations | [161] |

| 5 | Integration with Multi-Omics and Genetic Profiling | Combining metabolomics, proteomics, genomics with redox biomarkers | Identification of patient-specific redox phenotypes; targeted interventions for high-risk populations | Complex data interpretation; requires specialized infrastructure | [162] |

| 6 | Digital Health and Continuous Monitoring | Wearable devices and sensors to track endothelial function, arterial stiffness, oxidative stress | Dynamic adjustment of therapy; early detection of therapy failure; improved adherence | Technology validation; data privacy; integration into clinical workflow | [163] |

| 7 | Overall Integration | Multi-modal approach combining pharmacologic antioxidants, gene therapy, nanocarriers, standard drugs, and biomarker guidance | Optimized, personalized redox modulation; improved CVD outcomes; reduced adverse events | Requires robust clinical trials; regulatory approval; interdisciplinary coordination | [164] |

| S.N. | Design Element | Recommended Strategy | Scientific and Clinical Rationale | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Study population | Stratification based on baseline oxidative stress status | Improves patient selection and enhances the likelihood of detecting treatment effects | [165,166,167,168,169,170] |

| 2 | Antioxidant class | Use of targeted or pathway-specific antioxidants (e.g., mitochondria-targeted antioxidants, NOX inhibitors, Nrf2 modulators) | Avoids nonspecific ROS suppression and preserves physiological redox signaling | [168,169,174] |

| 3 | Dose selection | Biomarker-guided or adaptive dosing strategies | Accounts for dose-dependent effects and interindividual variability in redox balance | [166,174] |

| 4 | Oxidative stress assessment | Inclusion of validated, easily repeatable biomarkers (e.g., oxidized LDL, malondialdehyde, 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α, total antioxidant capacity) | Enables objective evaluation of drug-induced modulation of oxidative stress | [165,171,172,173,174] |

| 5 | Timing of biomarker measurement | Baseline and longitudinal assessment during and after intervention | Captures dynamic changes in redox status in response to therapy | [169,174] |

| 6 | Combination therapy | Evaluation of next-generation antioxidants in combination with standard cardiovascular drugs | Reflects real-world clinical practice and may enhance therapeutic efficacy | [174,175] |

| 7 | Statin–antioxidant interaction | Assessment of pleiotropic statin effects on oxidative stress and endothelial function | Statins reduce ROS generation and may synergize with targeted antioxidants | [175,176,177] |

| 8 | Clinical endpoints | Integration of redox biomarkers with conventional cardiovascular outcomes | Strengthens mechanistic interpretation and clinical relevance | [167,173,174] |

| 9 | Trial duration | Adequate follow-up to observe biochemical and vascular effects | Short-term trials may underestimate antioxidant benefits | [166,172,174] |

| 10 | Precision medicine approach | Adaptive or personalized trial designs based on oxidative stress response | Supports individualized therapy and improves translational success | [168,174] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Singh, D.D.; Yadav, D.K.; Shin, D. Next-Generation Antioxidants in Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanistic Insights and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020164

Singh DD, Yadav DK, Shin D. Next-Generation Antioxidants in Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanistic Insights and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(2):164. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020164

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Desh Deepak, Dharmendra Kumar Yadav, and Dongyun Shin. 2026. "Next-Generation Antioxidants in Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanistic Insights and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies" Antioxidants 15, no. 2: 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020164

APA StyleSingh, D. D., Yadav, D. K., & Shin, D. (2026). Next-Generation Antioxidants in Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanistic Insights and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Antioxidants, 15(2), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15020164