Author Contributions

Y.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Software, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. S.A.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Software, Writing—Original draft preparation. İ.Ö.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Software, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. M.C.T.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Software, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. Ş.Ö.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Software, Writing—Original draft preparation, Writing—Reviewing and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

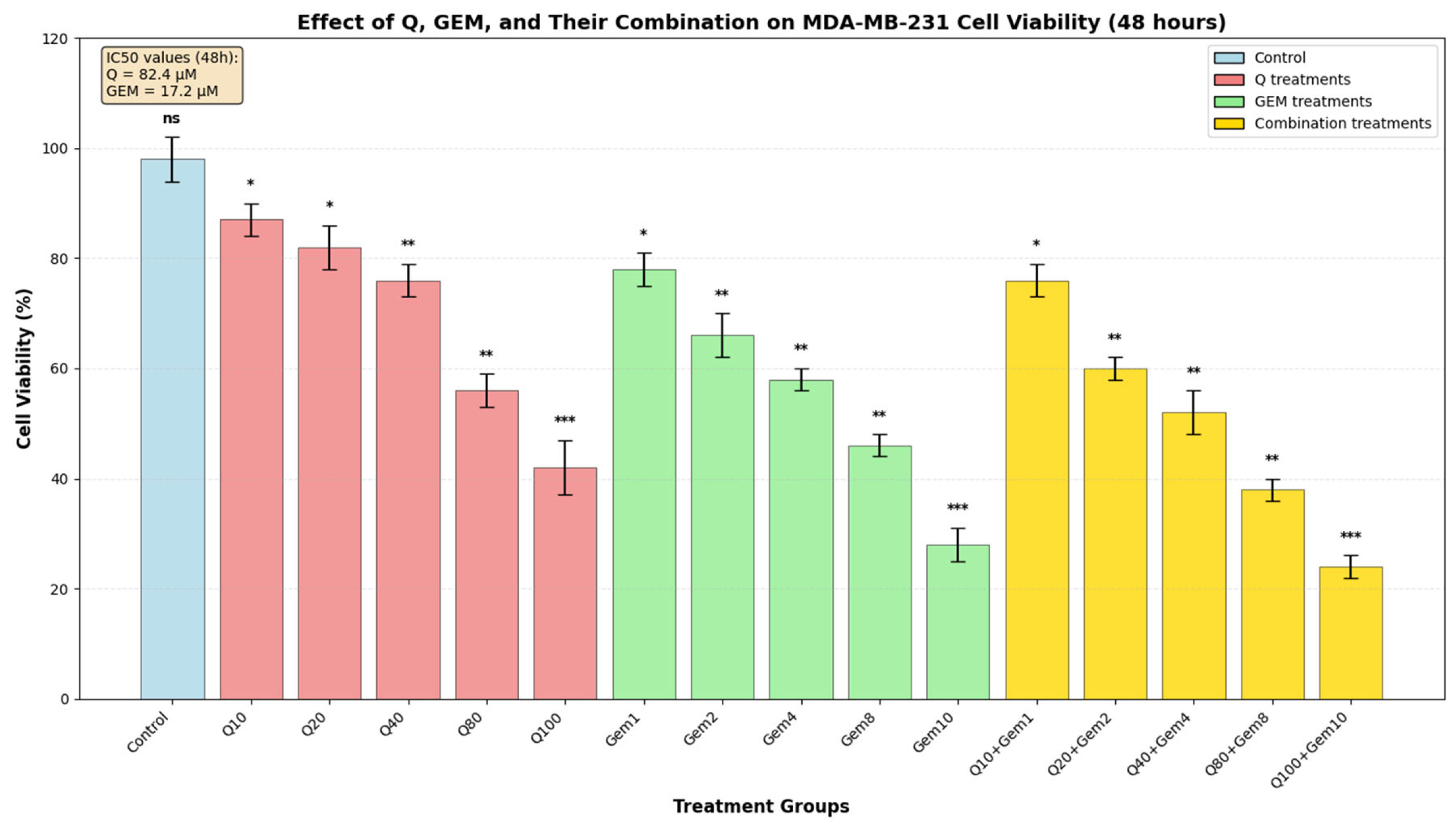

Figure 1.

Effect of Q, Gem, and their combination on MDA-MB-231 cell viability. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Q (0–100 µM), Gem (0–10 µM), and their fixed-ratio combinations (Q10 + GEM1, Q20 + GEM2, Q40 + GEM4, Q80 + GEM8, Q100 + GEM10) for 48 h. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay and expressed as a percentage of the control (mean ± SD, n = 3). Both agents exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity, with IC50 values of 82.4 µM for Q and 17.2 µM for Gem, calculated from dose–response curves. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ns, not significant).

Figure 1.

Effect of Q, Gem, and their combination on MDA-MB-231 cell viability. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of Q (0–100 µM), Gem (0–10 µM), and their fixed-ratio combinations (Q10 + GEM1, Q20 + GEM2, Q40 + GEM4, Q80 + GEM8, Q100 + GEM10) for 48 h. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay and expressed as a percentage of the control (mean ± SD, n = 3). Both agents exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxicity, with IC50 values of 82.4 µM for Q and 17.2 µM for Gem, calculated from dose–response curves. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ns, not significant).

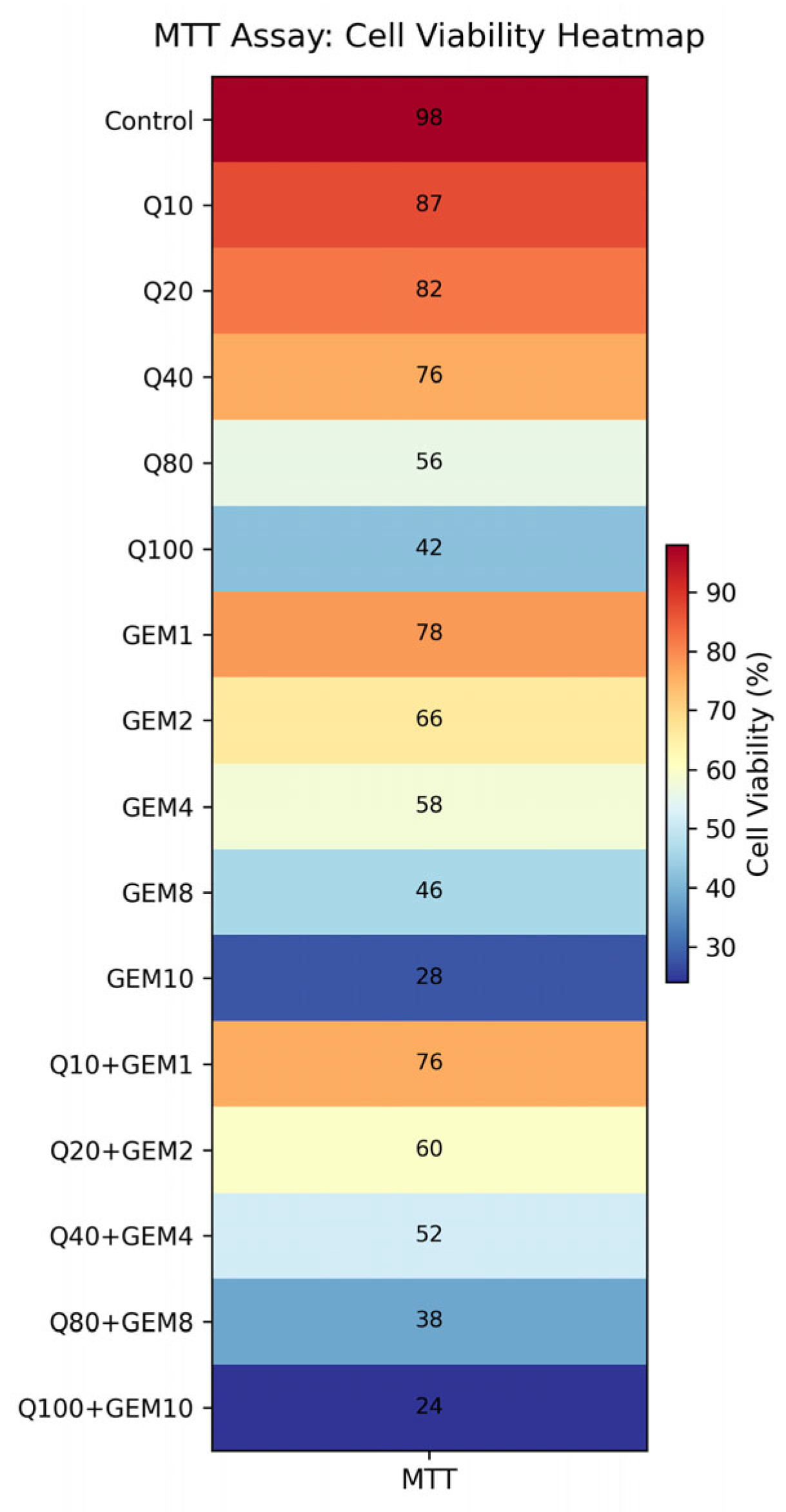

Figure 2.

Heatmap visualization of MTT-derived cell viability following treatment with Q, Gem, and their fixed-ratio combinations in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cell viability is expressed as a percentage relative to untreated control cells. The heatmap illustrates enhanced cytotoxic effects in the combination groups compared to single-agent treatments, with the most pronounced reduction in cell viability observed at IC50-based Q + GEM concentrations, supporting the synergistic interaction identified by CI and Bliss analyses.

Figure 2.

Heatmap visualization of MTT-derived cell viability following treatment with Q, Gem, and their fixed-ratio combinations in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cell viability is expressed as a percentage relative to untreated control cells. The heatmap illustrates enhanced cytotoxic effects in the combination groups compared to single-agent treatments, with the most pronounced reduction in cell viability observed at IC50-based Q + GEM concentrations, supporting the synergistic interaction identified by CI and Bliss analyses.

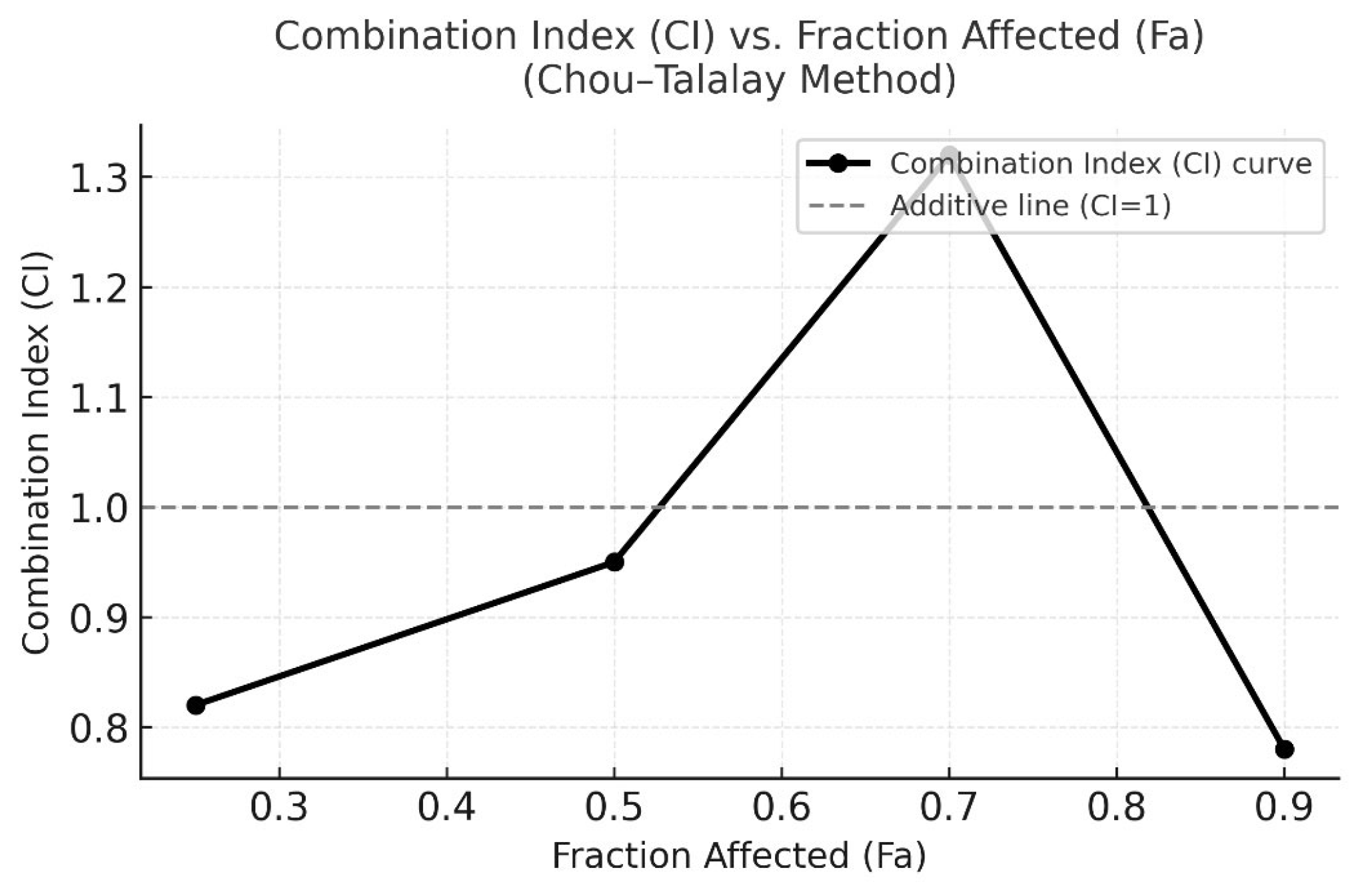

Figure 3.

CI versus Fraction Affected (Fa) plot according to the Chou–Talalay method. CI values were calculated using CompuSyn software based on the median-effect equation. CI < 1 indicates synergism, CI = 1 represents an additive effect, and CI > 1 indicates antagonism. The plot demonstrates that the combination of Q and Gem exhibits predominant synergistic interaction (CI < 1) across most effect levels, with the strongest synergy observed around Fa = 0.5 (IC50 region).

Figure 3.

CI versus Fraction Affected (Fa) plot according to the Chou–Talalay method. CI values were calculated using CompuSyn software based on the median-effect equation. CI < 1 indicates synergism, CI = 1 represents an additive effect, and CI > 1 indicates antagonism. The plot demonstrates that the combination of Q and Gem exhibits predominant synergistic interaction (CI < 1) across most effect levels, with the strongest synergy observed around Fa = 0.5 (IC50 region).

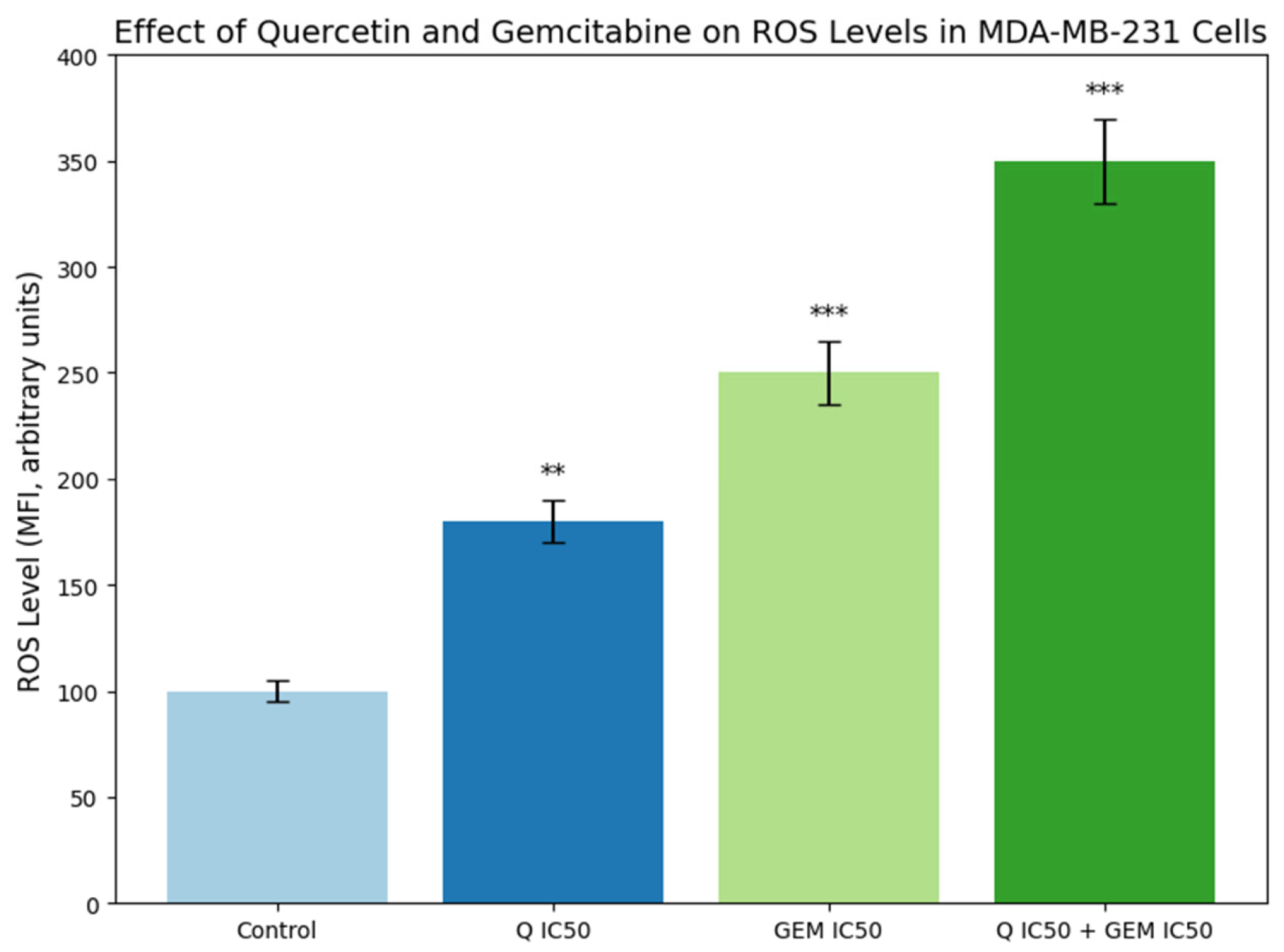

Figure 4.

Effect of Q and Gem on intracellular ROS levels in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated with Q and Gem at their IC50 concentrations, alone or in combination, for 48 h. Intracellular ROS was measured using the DCFDA fluorescent probe (λ_ex = 485 nm, λ_em = 530 nm) and expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI, arbitrary units) ± SD (n = 3). All treatments increased ROS compared with control, with the highest levels in the Q + Gem group, indicating enhanced oxidative stress and apoptosis. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***).

Figure 4.

Effect of Q and Gem on intracellular ROS levels in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated with Q and Gem at their IC50 concentrations, alone or in combination, for 48 h. Intracellular ROS was measured using the DCFDA fluorescent probe (λ_ex = 485 nm, λ_em = 530 nm) and expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI, arbitrary units) ± SD (n = 3). All treatments increased ROS compared with control, with the highest levels in the Q + Gem group, indicating enhanced oxidative stress and apoptosis. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***).

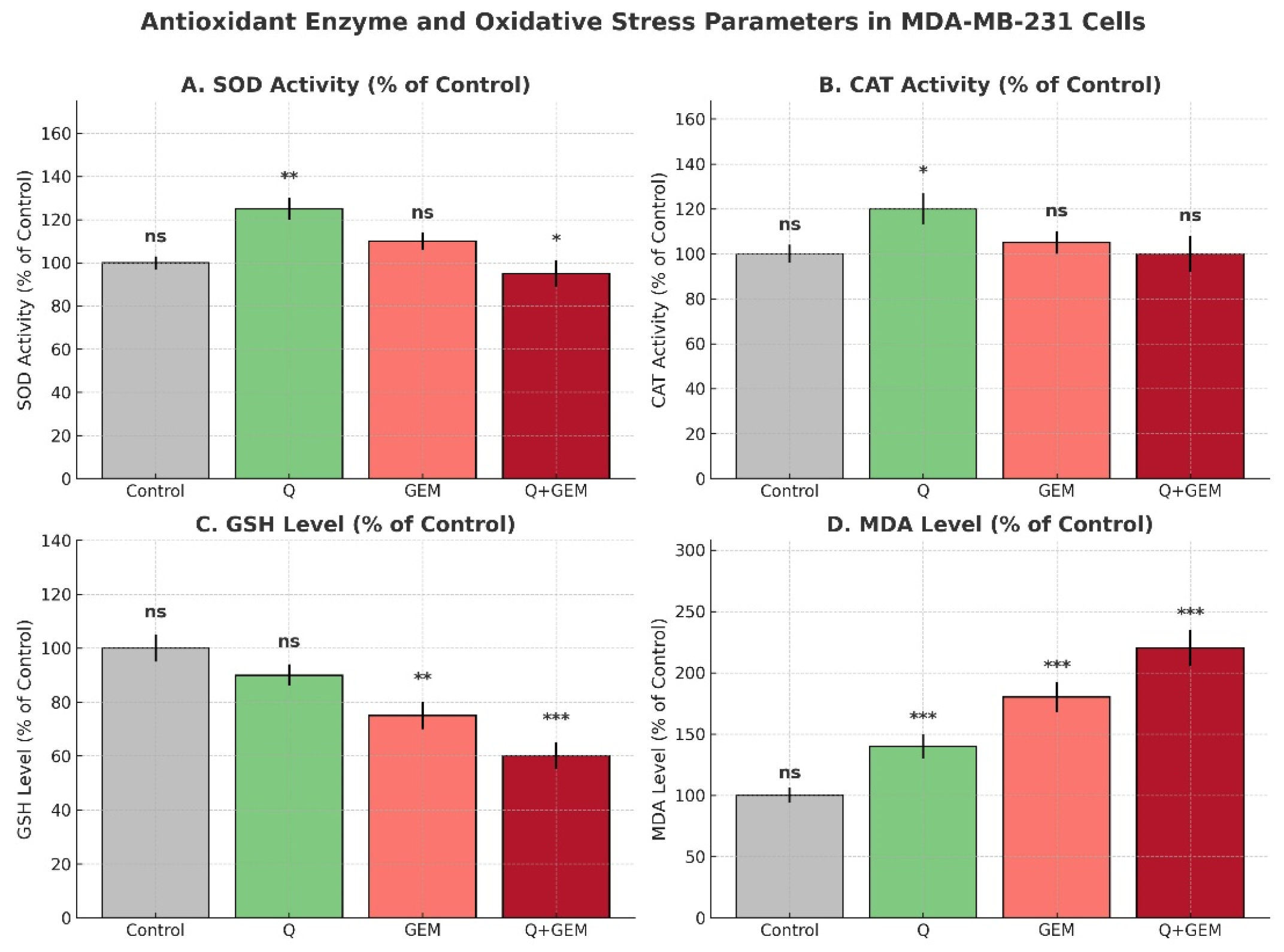

Figure 5.

Antioxidant defenses and oxidative stress parameters in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with Q, Gem, and their combination (Q + Gem). Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, CAT) were significantly increased by Q treatment, whereas non-enzymatic antioxidant GSH levels were markedly reduced by Gem and the combination treatment. Lipid peroxidation, assessed by MDA levels, was strongly elevated in Gem and combination groups, indicating enhanced oxidative stress. Values are expressed as percentages of the control (mean ± SD, n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test; significance versus control is indicated as p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***); ns = not significant.

Figure 5.

Antioxidant defenses and oxidative stress parameters in MDA-MB-231 cells after treatment with Q, Gem, and their combination (Q + Gem). Enzymatic antioxidants (SOD, CAT) were significantly increased by Q treatment, whereas non-enzymatic antioxidant GSH levels were markedly reduced by Gem and the combination treatment. Lipid peroxidation, assessed by MDA levels, was strongly elevated in Gem and combination groups, indicating enhanced oxidative stress. Values are expressed as percentages of the control (mean ± SD, n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test; significance versus control is indicated as p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***); ns = not significant.

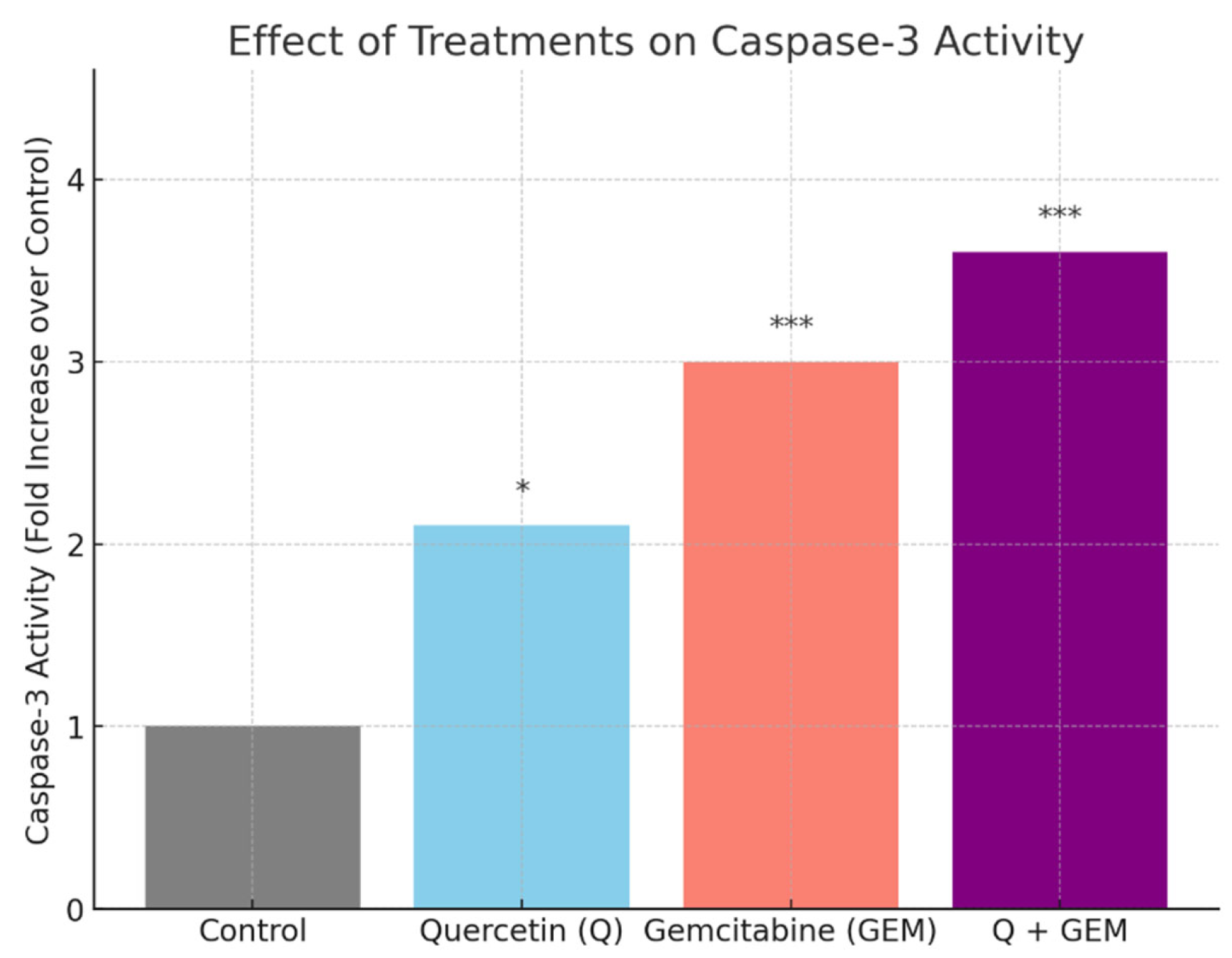

Figure 6.

Effect of Q, Gem, and their combination on caspase-3 activity in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated for 48 h with Q (82.4 µM), Gem (17.2 µM), or Q + Gem at IC50 doses. Caspase-3 activity was measured colorimetrically using the DEVD-pNA substrate. Data are presented as fold change relative to control (mean ± SD, n = 3). Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (* p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Effect of Q, Gem, and their combination on caspase-3 activity in MDA-MB-231 cells. Cells were treated for 48 h with Q (82.4 µM), Gem (17.2 µM), or Q + Gem at IC50 doses. Caspase-3 activity was measured colorimetrically using the DEVD-pNA substrate. Data are presented as fold change relative to control (mean ± SD, n = 3). Statistical analysis: one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (* p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001).

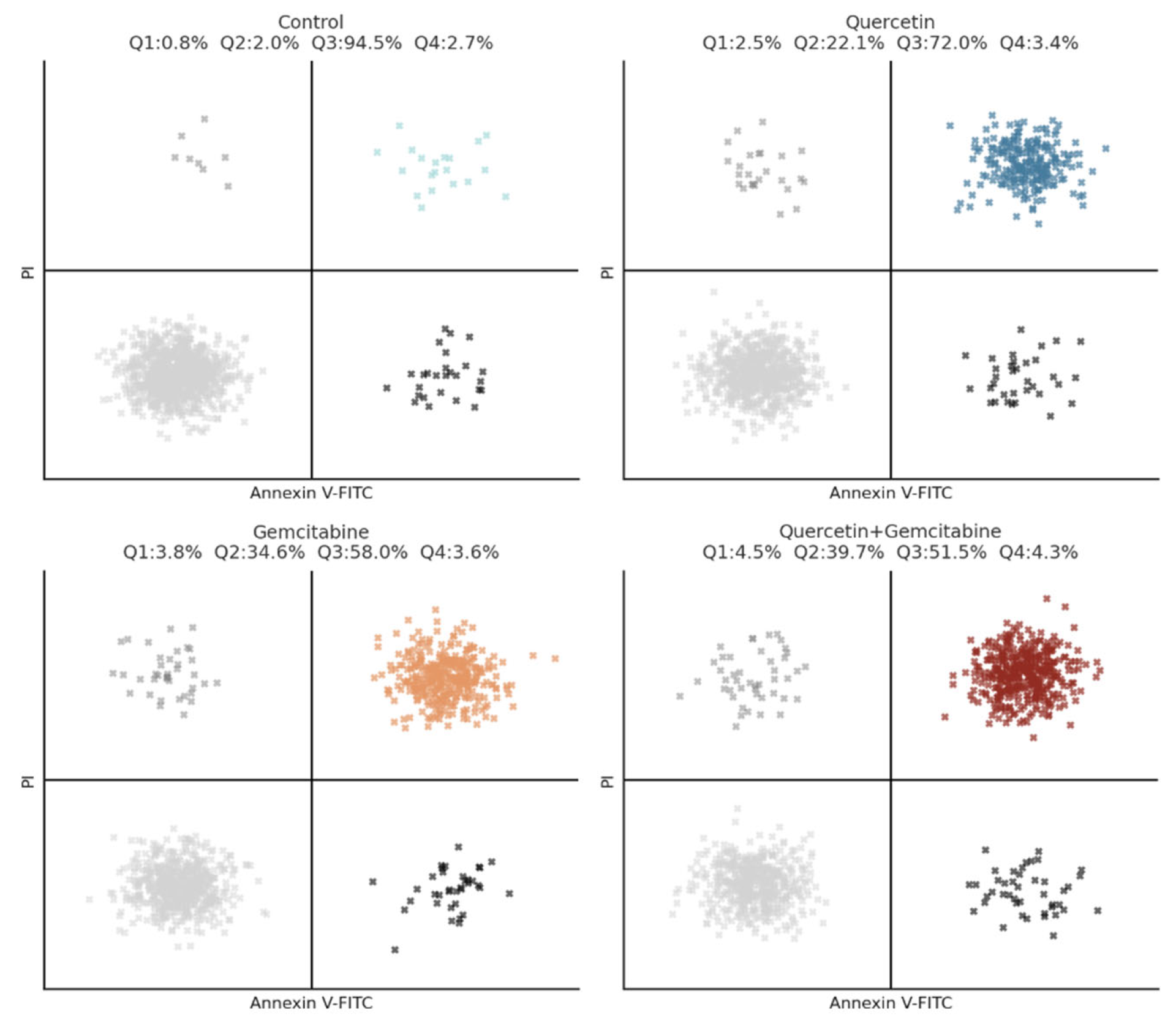

Figure 7.

Annexin V-FITC/PI flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Q, Gem, and their combination. Cells were exposed for 48 h to Q, Gem and Q + Gem at IC50 doses and stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI. Representative dot plots for each group are shown. Quadrants: Q1 = necrotic (Annexin−/PI+), Q2 = late apoptotic (Annexin+/PI+), Q3 = early apoptotic (Annexin+/PI−), Q4 = viable cells (Annexin−/PI−). Total apoptosis increased from 2.8% (control) to 24.6% (Q), 38.4% (Gem), and 44.2% (Q + Gem), demonstrating a clear enhancement of apoptotic cell death by the combination treatment.

Figure 7.

Annexin V-FITC/PI flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Q, Gem, and their combination. Cells were exposed for 48 h to Q, Gem and Q + Gem at IC50 doses and stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI. Representative dot plots for each group are shown. Quadrants: Q1 = necrotic (Annexin−/PI+), Q2 = late apoptotic (Annexin+/PI+), Q3 = early apoptotic (Annexin+/PI−), Q4 = viable cells (Annexin−/PI−). Total apoptosis increased from 2.8% (control) to 24.6% (Q), 38.4% (Gem), and 44.2% (Q + Gem), demonstrating a clear enhancement of apoptotic cell death by the combination treatment.

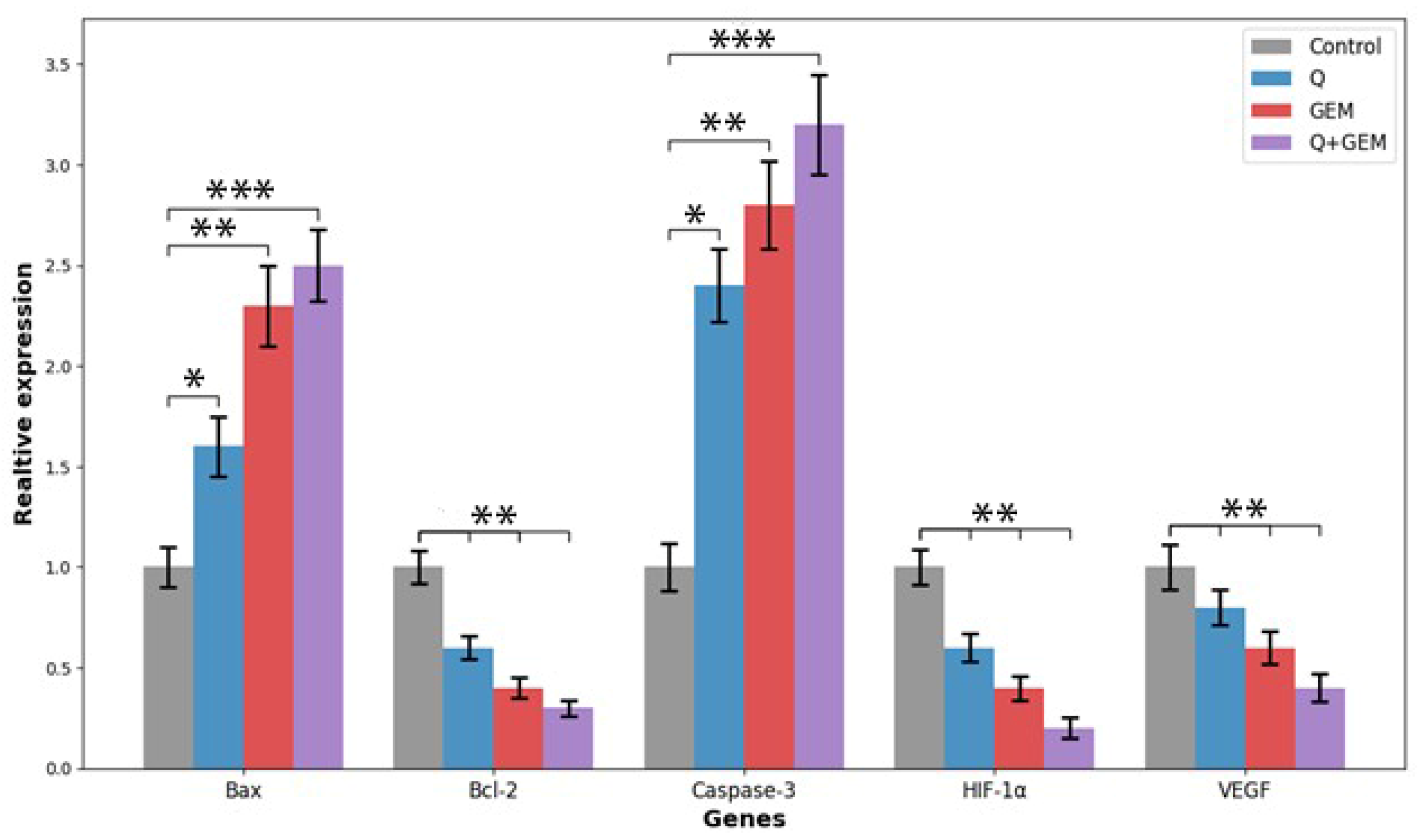

Figure 8.

Relative mRNA expression levels of apoptosis-, hypoxia-, and angiogenesis-related genes (Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, HIF-1α, and VEGF) in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Q, Gem, and their combination (Q + Gem). Cells were treated for 48 h with Q, Gem and their combination at IC50 concentrations. Gene expression levels were quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using β-actin as the internal control, and relative expression was calculated by the 2^–ΔΔCt method. Combination treatment markedly increased Bax and Caspase-3 expression while decreasing Bcl-2, consistent with activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Concurrently, HIF-1α and VEGF transcripts were significantly downregulated, indicating suppression of hypoxia-induced angiogenic signaling. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. control.

Figure 8.

Relative mRNA expression levels of apoptosis-, hypoxia-, and angiogenesis-related genes (Bax, Bcl-2, Caspase-3, HIF-1α, and VEGF) in MDA-MB-231 cells treated with Q, Gem, and their combination (Q + Gem). Cells were treated for 48 h with Q, Gem and their combination at IC50 concentrations. Gene expression levels were quantified by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using β-actin as the internal control, and relative expression was calculated by the 2^–ΔΔCt method. Combination treatment markedly increased Bax and Caspase-3 expression while decreasing Bcl-2, consistent with activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Concurrently, HIF-1α and VEGF transcripts were significantly downregulated, indicating suppression of hypoxia-induced angiogenic signaling. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. control.

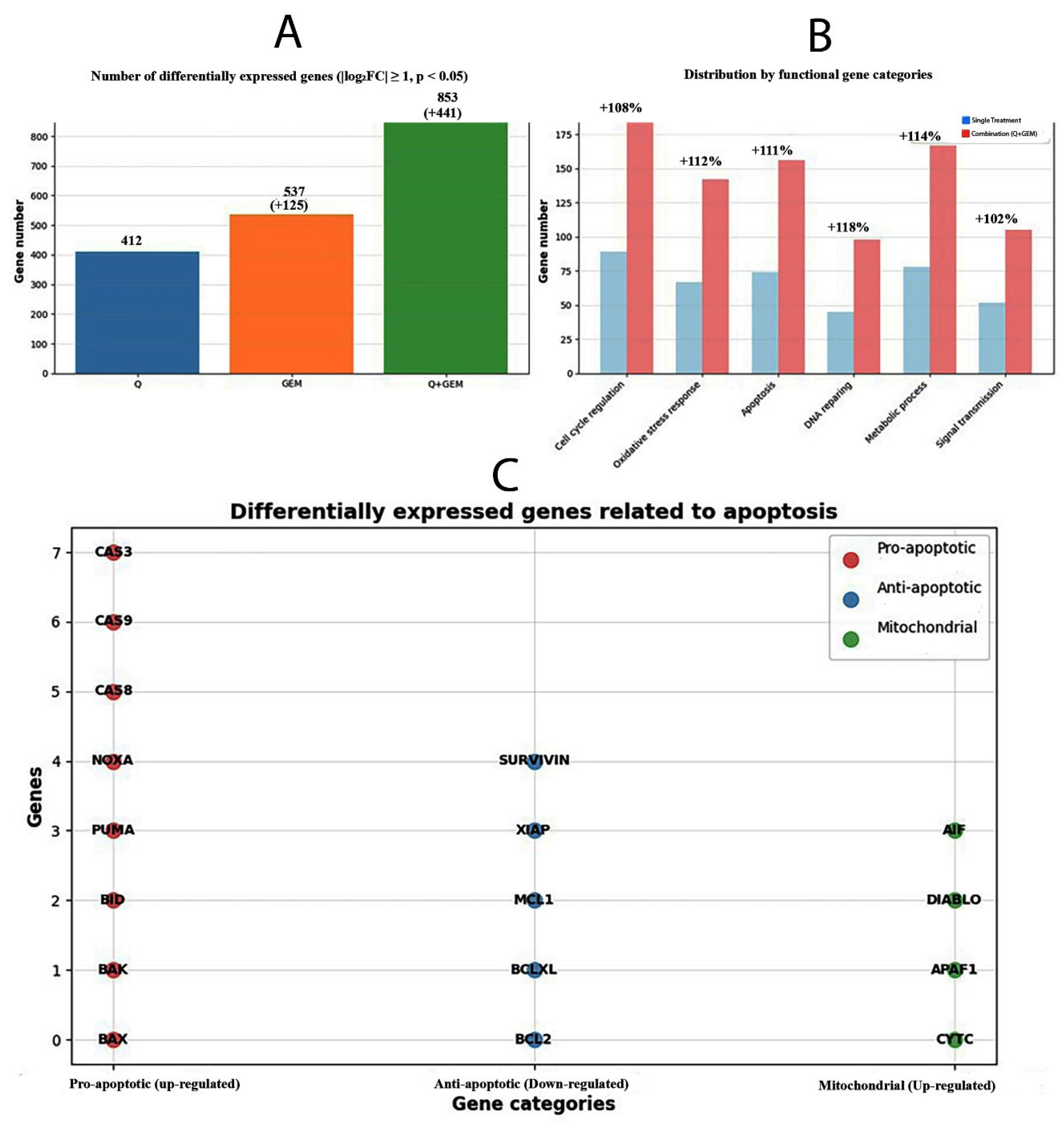

Figure 9.

Transcriptomic and functional categorization of differentially expressed genes after Q, Gem, and combination (Q + Gem) treatments. (A) The total number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified for each treatment condition (|log2FC| ≥ 1, p < 0.05). Combination treatment (Q + Gem) modulated the largest number of genes (853), approximately twice that of single treatments, indicating enhanced transcriptional reprogramming. (B) Distribution of DEGs by functional gene categories. Combination treatment markedly increased gene counts associated with cell cycle regulation (+108%), oxidative stress response (+112%), apoptosis (+111%), DNA repair (+118%), metabolic process (+114%), and signal transduction (+102%) compared with single-agent treatments. (C) Differentially expressed genes related to apoptosis classified by function. Pro-apoptotic (up-regulated, red), anti-apoptotic (down-regulated, blue), and mitochondrial (up-regulated, green) genes are shown. The upregulation of CASP3, BAX, NOXA, and DIABLO, along with downregulation of BCL2 and XIAP, supports activation of the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in Q + Gem-treated MDA-MB-231 cells.

Figure 9.

Transcriptomic and functional categorization of differentially expressed genes after Q, Gem, and combination (Q + Gem) treatments. (A) The total number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified for each treatment condition (|log2FC| ≥ 1, p < 0.05). Combination treatment (Q + Gem) modulated the largest number of genes (853), approximately twice that of single treatments, indicating enhanced transcriptional reprogramming. (B) Distribution of DEGs by functional gene categories. Combination treatment markedly increased gene counts associated with cell cycle regulation (+108%), oxidative stress response (+112%), apoptosis (+111%), DNA repair (+118%), metabolic process (+114%), and signal transduction (+102%) compared with single-agent treatments. (C) Differentially expressed genes related to apoptosis classified by function. Pro-apoptotic (up-regulated, red), anti-apoptotic (down-regulated, blue), and mitochondrial (up-regulated, green) genes are shown. The upregulation of CASP3, BAX, NOXA, and DIABLO, along with downregulation of BCL2 and XIAP, supports activation of the intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in Q + Gem-treated MDA-MB-231 cells.

![Antioxidants 15 00091 g009 Antioxidants 15 00091 g009]()

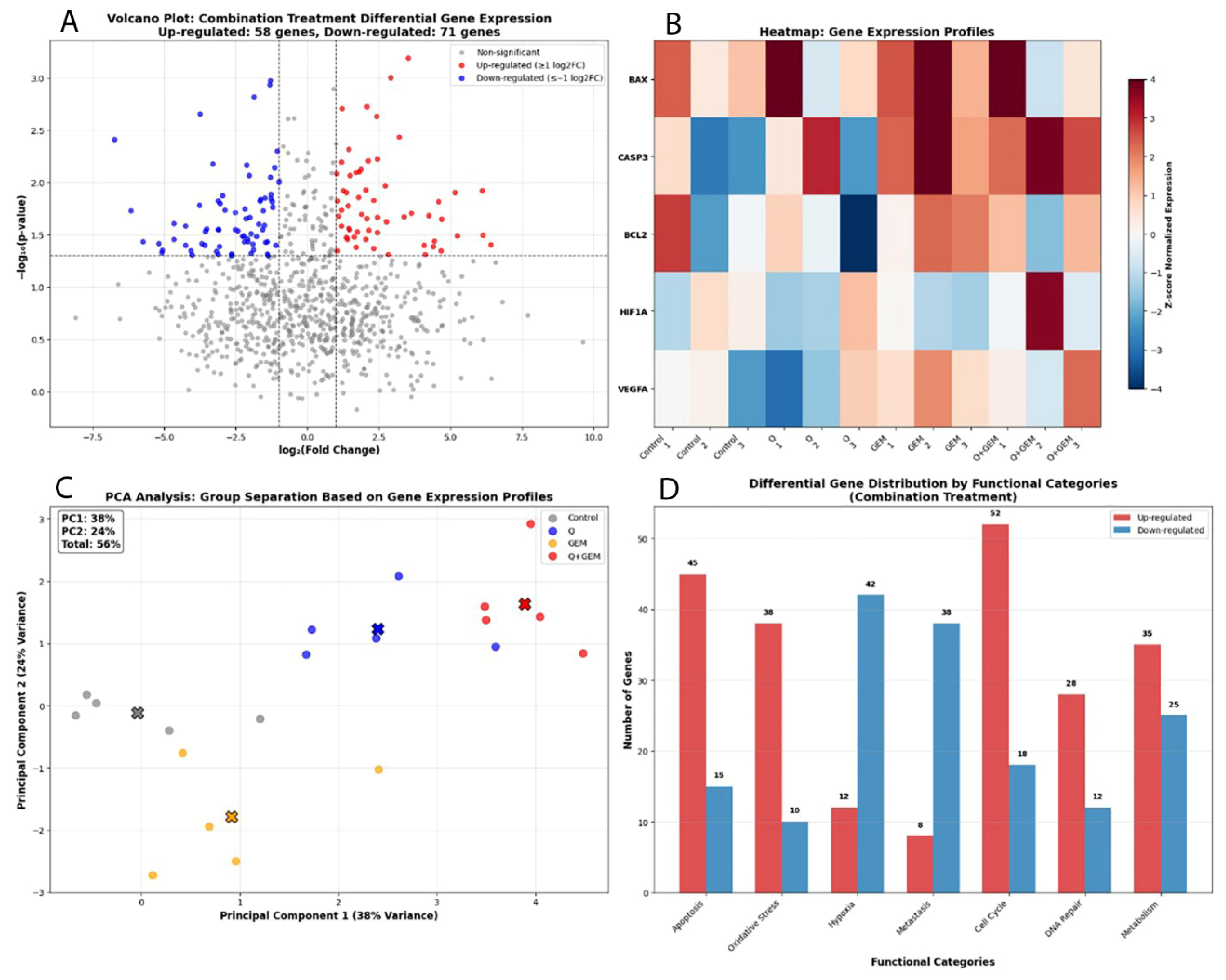

Figure 10.

Transcriptomic profiling of gene expression alterations induced by Q, Gem, and their combination (Q + Gem) in MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Volcano plot showing significantly upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes in the combination treatment (|log2FC| ≥ 1, p < 0.05). Upregulated genes were primarily associated with apoptotic signaling and oxidative stress response, whereas downregulated genes were linked to hypoxia and metastatic processes. (B) Heatmap of the top differentially expressed genes, illustrating distinct expression patterns between control, single-agent, and combination groups. Notably, BAX and CASP3 were markedly upregulated, while HIF1α, VEGFA, and BCL2 were downregulated in the combination group, confirming synergistic pro-apoptotic and anti-angiogenic effects. (C) PCA (Principal Component Analysis) showing clear segregation of the combination group (Q + Gem) from control and single-agent treatments. PC1 and PC2 accounted for 38% and 24% of the total variance, respectively (cumulative 56%), indicating distinct transcriptional reprogramming under combined treatment. (D) Differential gene distribution by functional categories in the combination group. Genes related to apoptosis (45 upregulated, 15 downregulated), oxidative stress (38 upregulated, 10 downregulated), and cell cycle control (52 upregulated, 18 downregulated) showed predominant upregulation, reflecting enhanced activation of pro-apoptotic and stress-related molecular pathways.

Figure 10.

Transcriptomic profiling of gene expression alterations induced by Q, Gem, and their combination (Q + Gem) in MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Volcano plot showing significantly upregulated (red) and downregulated (blue) genes in the combination treatment (|log2FC| ≥ 1, p < 0.05). Upregulated genes were primarily associated with apoptotic signaling and oxidative stress response, whereas downregulated genes were linked to hypoxia and metastatic processes. (B) Heatmap of the top differentially expressed genes, illustrating distinct expression patterns between control, single-agent, and combination groups. Notably, BAX and CASP3 were markedly upregulated, while HIF1α, VEGFA, and BCL2 were downregulated in the combination group, confirming synergistic pro-apoptotic and anti-angiogenic effects. (C) PCA (Principal Component Analysis) showing clear segregation of the combination group (Q + Gem) from control and single-agent treatments. PC1 and PC2 accounted for 38% and 24% of the total variance, respectively (cumulative 56%), indicating distinct transcriptional reprogramming under combined treatment. (D) Differential gene distribution by functional categories in the combination group. Genes related to apoptosis (45 upregulated, 15 downregulated), oxidative stress (38 upregulated, 10 downregulated), and cell cycle control (52 upregulated, 18 downregulated) showed predominant upregulation, reflecting enhanced activation of pro-apoptotic and stress-related molecular pathways.

![Antioxidants 15 00091 g010 Antioxidants 15 00091 g010]()

Figure 11.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in the Q and Gem combination group. Bubble plot representing the significantly enriched GO biological processes (blue) and KEGG signaling pathways (red) associated with the combination treatment in MDA-MB-231 cells. The x-axis indicates the enrichment significance (−log10 p-value), and the bubble size corresponds to the number of genes involved in each term. Key enriched GO terms included apoptotic process, response to hypoxia, and angiogenesis, while KEGG pathway enrichment highlighted PI3K/Akt, MAPK, HIF-1, and VEGF signaling pathways. These results indicate that the combination treatment exerts its synergistic antitumor effects by activating apoptotic and stress-response pathways and suppressing angiogenic and hypoxia-related mechanisms.

Figure 11.

GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in the Q and Gem combination group. Bubble plot representing the significantly enriched GO biological processes (blue) and KEGG signaling pathways (red) associated with the combination treatment in MDA-MB-231 cells. The x-axis indicates the enrichment significance (−log10 p-value), and the bubble size corresponds to the number of genes involved in each term. Key enriched GO terms included apoptotic process, response to hypoxia, and angiogenesis, while KEGG pathway enrichment highlighted PI3K/Akt, MAPK, HIF-1, and VEGF signaling pathways. These results indicate that the combination treatment exerts its synergistic antitumor effects by activating apoptotic and stress-response pathways and suppressing angiogenic and hypoxia-related mechanisms.

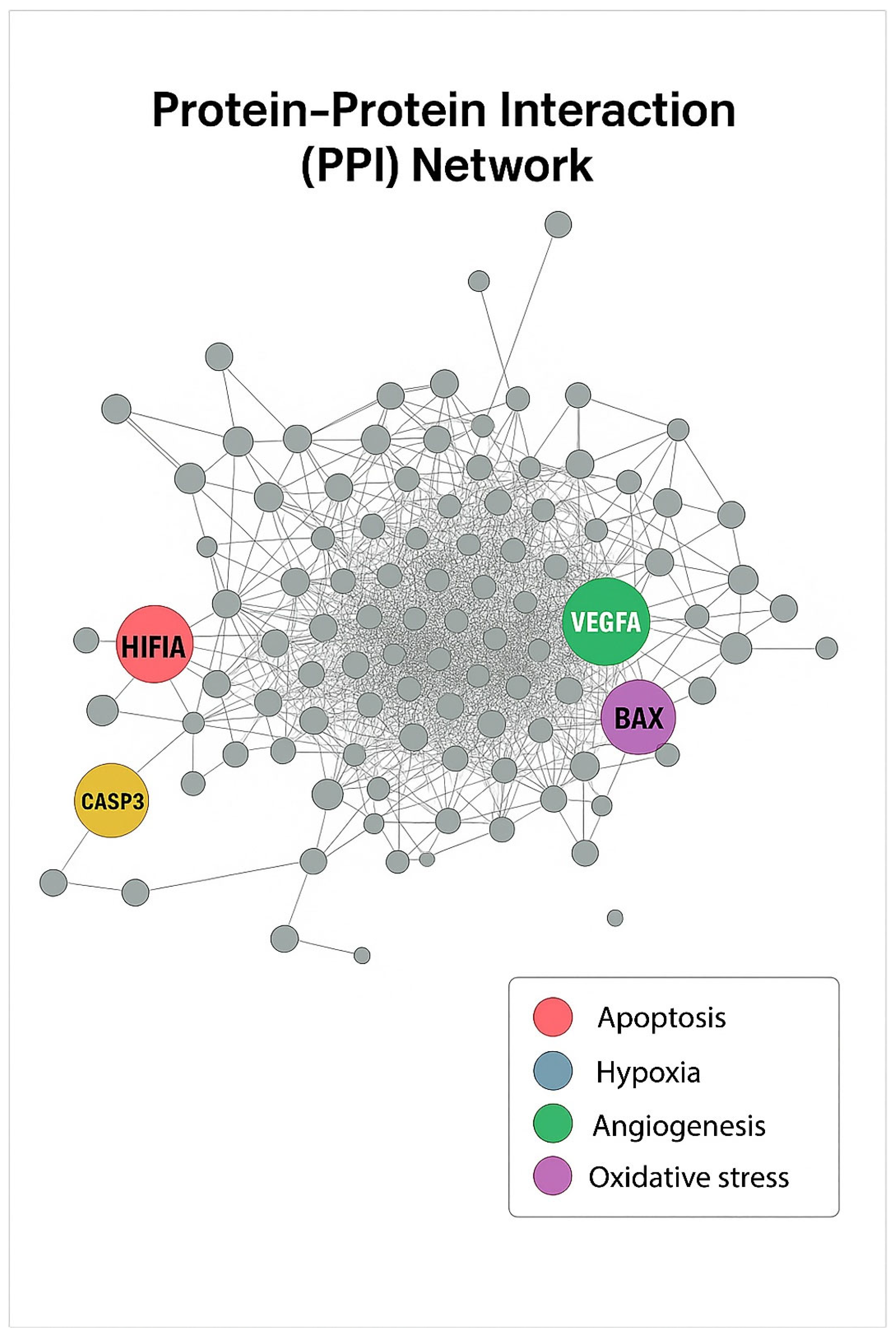

Figure 12.

PPI Network. The PPI network was constructed using STRING (v12) and visualized in Cytoscape (v3.10). Each node represents a differentially expressed gene, and edges indicate protein–protein associations. Hub genes with high connectivity were identified as HIF1α (blue, hypoxia), CASP3 (red, apoptosis), VEGFA (green, angiogenesis), and BAX (purple, oxidative stress). These central nodes are proposed to mediate key molecular interactions underlying the combined antitumor effects of Q and Gem.

Figure 12.

PPI Network. The PPI network was constructed using STRING (v12) and visualized in Cytoscape (v3.10). Each node represents a differentially expressed gene, and edges indicate protein–protein associations. Hub genes with high connectivity were identified as HIF1α (blue, hypoxia), CASP3 (red, apoptosis), VEGFA (green, angiogenesis), and BAX (purple, oxidative stress). These central nodes are proposed to mediate key molecular interactions underlying the combined antitumor effects of Q and Gem.

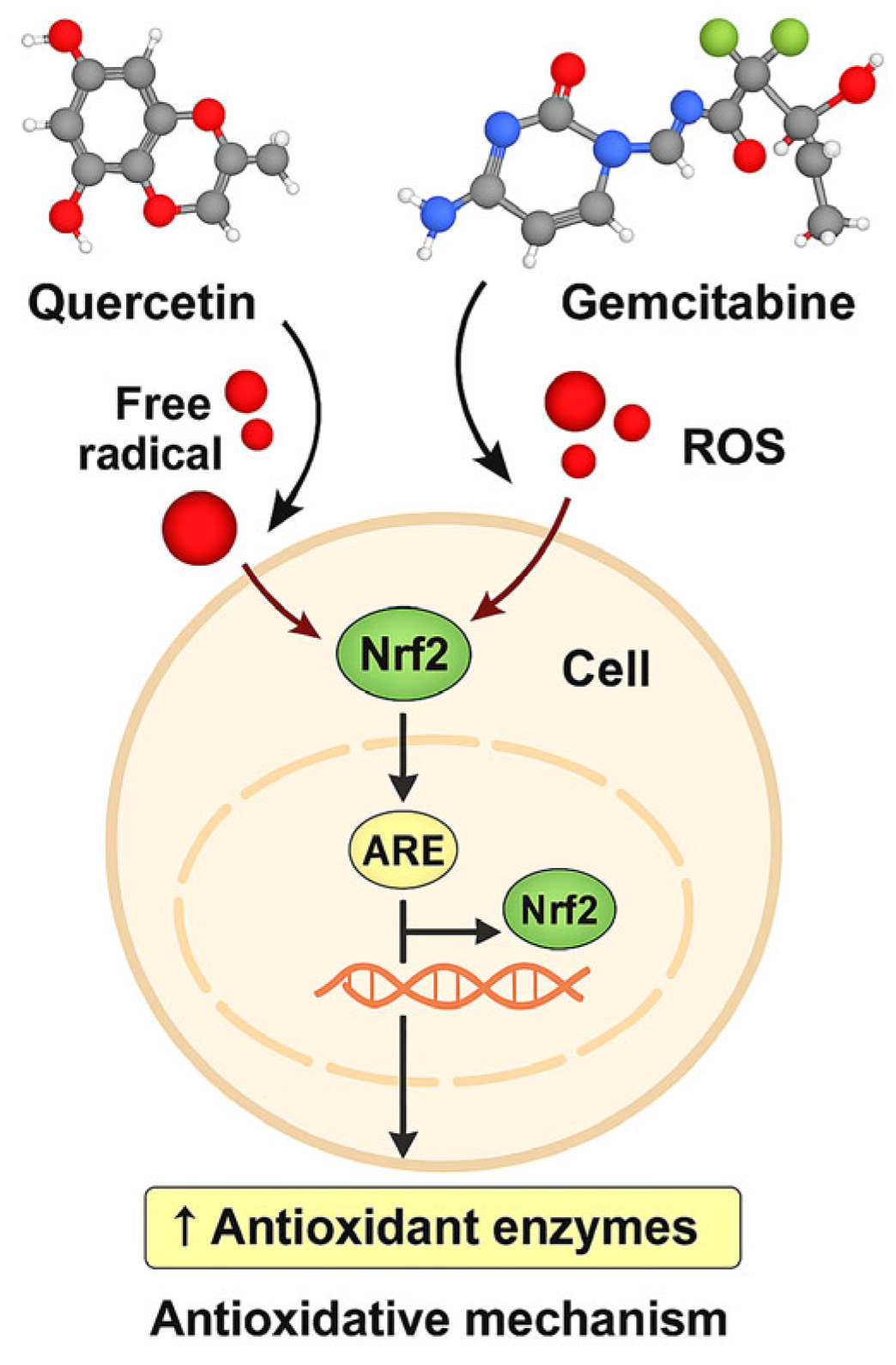

Figure 13.

Schematic of the proposed Nrf2/ARE-centered redox mechanism of Q and GEM in MDA-MB-231 cells. Q modulates ROS and activates Nrf2/ARE, inducing antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT), while GEM increases ROS. Combined treatment overwhelms antioxidant defenses, causing GSH depletion, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis (↑Bax, ↑Caspase-3, ↓Bcl-2), alongside downregulation of HIF-1α/VEGF, suppressing survival and angiogenesis.

Figure 13.

Schematic of the proposed Nrf2/ARE-centered redox mechanism of Q and GEM in MDA-MB-231 cells. Q modulates ROS and activates Nrf2/ARE, inducing antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT), while GEM increases ROS. Combined treatment overwhelms antioxidant defenses, causing GSH depletion, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis (↑Bax, ↑Caspase-3, ↓Bcl-2), alongside downregulation of HIF-1α/VEGF, suppressing survival and angiogenesis.