Abstract

It is well known that coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) has important antioxidant properties. Because one of the main mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative diseases is oxidative stress, analysis of the concentrations of CoQ10 in different tissues of AD patients and with other dementia syndromes and the possible therapeutic role of CoQ10 in AD have been addressed in several studies. We performed a systematic review and a meta-analysis of these studies measuring tissue CoQ10 levels in patients with dementia and controls which showed that, compared with controls, AD patients had similar serum/plasma CoQ10 levels. We also revised the possible therapeutic effects of CoQ10 in experimental models of AD and other dementias (which showed important neuroprotective effects of coenzyme Q10) and in humans with AD, other dementias, and mild cognitive impairment (with inconclusive results). The potential role of CoQ10 treatment in AD and in improving memory in aged rodents shown in experimental models deserves future studies in patients with AD, other causes of dementia, and mild cognitive impairment.

1. Introduction

The 1,4-benzoquinone ubiquinone or coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), which is present in the majority of tissues in the human body, is an important component of the mitochondrial electron transport, participating in the generation of cellular energy through oxidative phosphorylation, and can be present in tissues in three different redox states: fully reduced (ubiquinol), fully oxidized (ubiquinone), and partially oxidized (semiquinone or ubisemiquinone). In addition to mitochondria, CoQ10 is present in peroxisomes, lysosomes, and the Golgi apparatus. CoQ10 has important antioxidant properties, with both a direct antioxidant effect of scavenging free radicals, and an indirect one of participating in the regeneration of other antioxidants such as ascorbic acid and alpha-tocopherol, offering protection to cells against oxidative stress processes [1,2].

It is well known that one of the most important pathogenetic mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative disorders is oxidative stress [3,4,5]. Due to the important antioxidant functions of CoQ10, several publications over the last two decades have addressed the issues of both determinations of CoQ10 levels in different tissues of patients diagnosed with AD or other types of dementia and on the potential therapeutic role of CoQ10 in these diseases (considering experimental studies in animal models of dementia in humans suffering from AD or other dementias). This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to analyze the results of studies addressing the tissular concentrations of CoQ10 in patients diagnosed with AD and other dementia syndromes compared with healthy controls, and the results of therapeutic trials of CoQ10 in AD (including experimental models of this disease) and in other causes of dementia.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Criteria for Eligibility of Studies

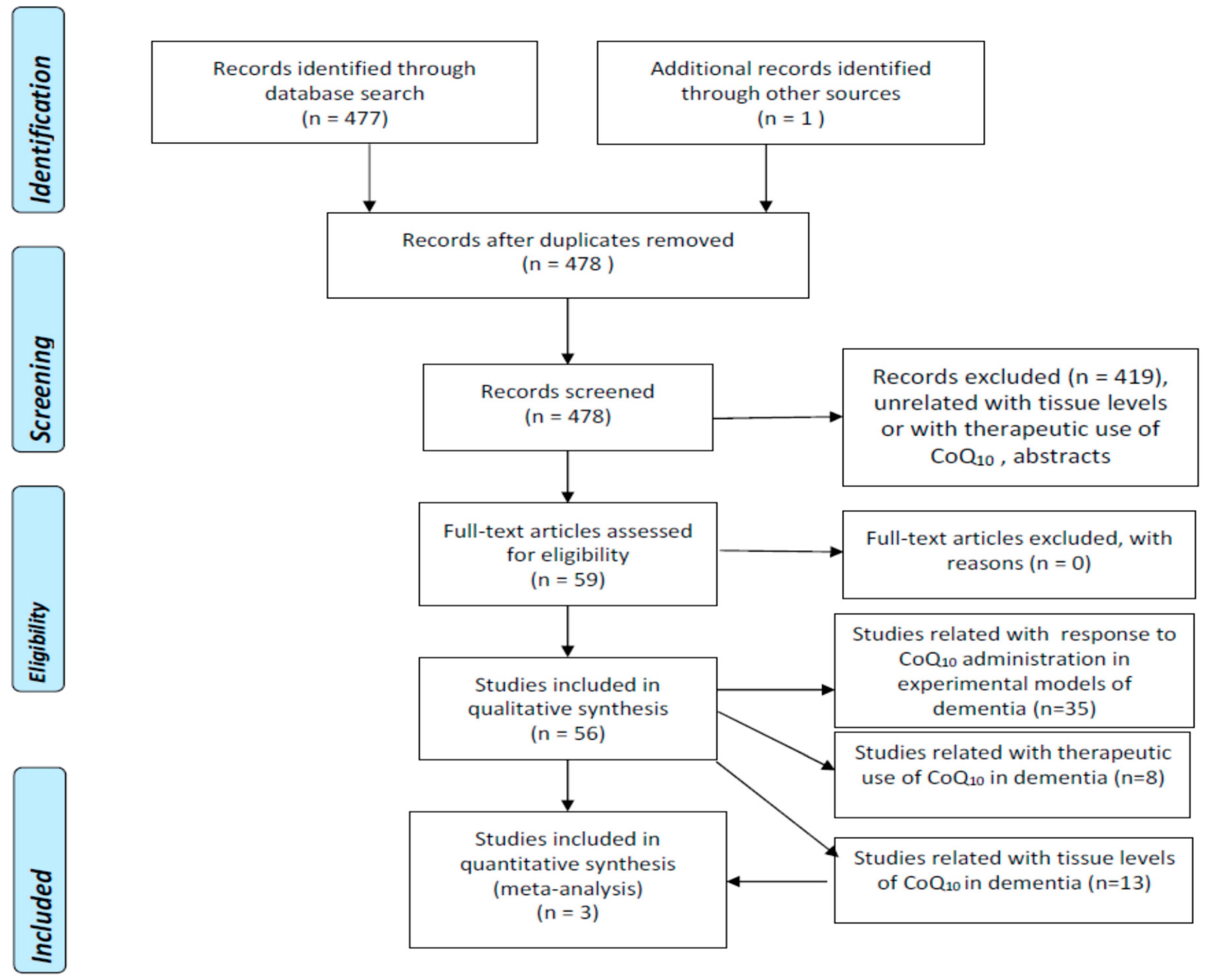

We undertook a literature search using 3 well-known databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science-WOS-Main Collection) from 1966 until 31 December 2022. We crossed the term “coenzyme Q10” with “Alzheimer’s disease” (188, 403, and 171 items found in PubMed, EMBASE, and WOS, respectively), “dementia” (222, 79, and 86 items found in PubMed, EMBASE, and WOS, respectively), “vascular dementia” (13, 9, and 8 items found in PubMed, EMBASE, and WOS, respectively), “Lewy body dementia” (9, 8, and 11 items found in PubMed, EMBASE, and WOS, respectively) “Lewy body disease” (9, 15, and 25 items found in PubMed, EMBASE, and WOS, respectively), and “mild cognitive impairment” (68, 19, and 34 items found in PubMed, EMBASE, and WOS, respectively). The search retrieved 477 references which were examined one by one by the authors in order to select exclusively those strictly related to the proposed topic. Duplicated articles and abstracts were excluded. We did not apply any language restrictions. Figure 1 represents the flowcharts for the selection of eligible studies which analyzed tissue CoQ10 concentrations in patients with different types of dementia, and therapeutic trials with CoQ10 in experimental models of dementia or in patients with AD or other dementias according to the PRISMA guidelines [6].

Figure 1.

Flowchart for studies assessing tissue concentrations of coenzyme Q10 in dementia (PRISMA) (6, 17).

2.2. Selection of Studies and Methodology for the Meta-Analyses

We performed a meta-analysis of observational eligible studies assessing the concentrations of CoQ10 in tissues of patients diagnosed with AD and/or other causes of dementia and in controls. We extracted the following information: first author, year of publication, country, study design, and quantitative measures. We analyzed the risk for bias with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [7]. Table 1 summarizes data from selected studies analyzing tissular concentrations of CoQ10 in patients diagnosed with AD, Lewy body dementia (LBD), vascular dementia (VD), and dementia without specification of etiology compared with controls (with the exception of one study that compares the serum/plasma CoQ10 of patients with dementia with reference values).

Table 1.

Coenzyme Q10 concentrations in several tissues from dementia patients and healthy controls (HC).

We converted plasma/serum and CSF CoQ10 concentrations to nmol/mL when necessary. The meta-analyses were carried out using the R software package meta [16] and following both the PRISMA [6] (Table S1) and the MOOSE guidelines [17] (Table S2). Because of the high heterogeneity across studies, we applied the random-effects model and used the inverse variance method for the meta-analytical procedure, the DerSimonian–Laird as an estimator for Tau2 [18], the Jackson method for the confidence interval of tau2 and tau [19], and the Hedges’ g (bias-corrected standardized mean difference) [20]. The statistical power to detect differences in mean values (alpha = 0.05) for the pooled samples was calculated when stated in the text. The meta-analysis was finally only applicable to three studies on serum/plasma CoQ10 concentrations in patients with AD compared with controls.

3. Results

3.1. Studies Assessing Tissular CoQ10 Concentrations

3.1.1. Alzheimer’s Disease

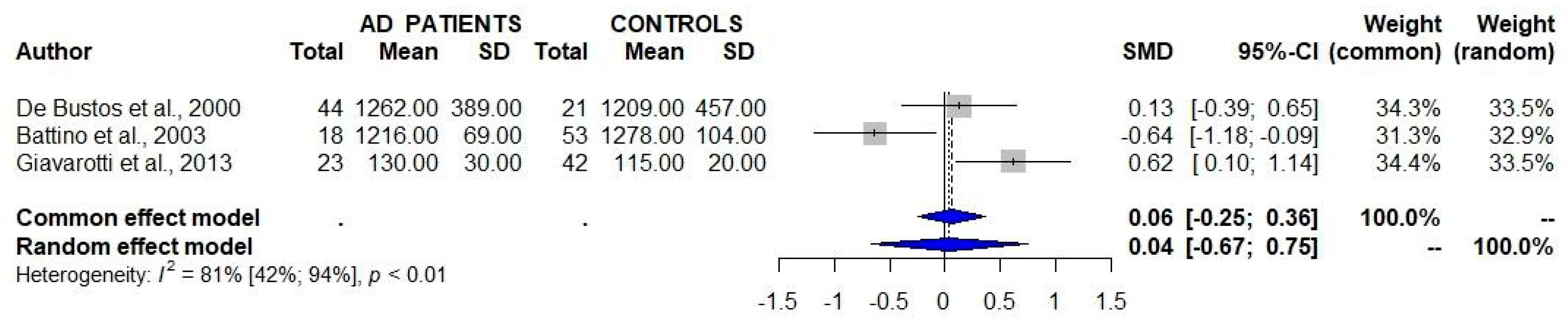

A total of three studies that assessed the serum/plasma levels of CoQ10 in patients with AD and controls failed to detect significant differences between the two study groups (Table 1, Figure 2) [8,9,10]. One of these studies showed a similar serum/plasma CoQ10/cholesterol ratio between AD patients and controls [8].

Figure 2.

Studies assessing the serum/plasma levels of CoQ10 in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and controls show a lack of significant differences between the two groups. 95% CI 95% confidence intervals; SMD standard mean difference [8,9,10].

Isobe et al. [11,12] reported increased total CoQ10 and oxidized CoQ10 concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid from AD patients compared with controls, and a negative correlation between oxidized/total coenzyme Q10 and duration of the disease.

To date, only two studies have addressed brain CoQ10 concentrations in patients with AD. Edlund et al. [21] described the mean values (without SD) of CoQ10 in frontal, precentral, temporal, and occipital cortex, and in nucleus caudate, hippocampus, pons, cerebellum, and medulla oblongata of AD patients and controls. They reported a 30–100% increase in CoQ10 concentrations in most of these regions; however, the number of AD patients and controls involved in the study was not stated. Kim et al. [22] described a decreased activity of the 25 kDa subunit nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide + hydrogen (NADH):ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) in the temporal and occipital cortex and of the 75 kDa subunit of this enzyme in the parietal cortex of patients with AD compared with controls, but specific measures of CoQ10 were not performed.

Santa-Mara et al. [23] reported the presence of CoQ10 in paired helical filaments (aberrant protein aggregates containing tau protein) and in Hirano bodies (neuronal inclusions that are mainly observed in hippocampal neurons and are composed of actin either associated with or not associated with tau) in brain patients with AD, and state that CoQ10 was able to induce the formation of aggregates when it was mixed with tau and actin.

3.1.2. Other Causes of Dementia

Serum CoQ10 concentrations and CoQ10/cholesterol ratios from patients diagnosed with LBD [13] and VD [8] did not differ significantly from those of controls according to two single studies.

Yamagishi et al. [14], in a community-based cohort study in Japan involving 6000 Japanese participants aged 40–69 years at baseline, described an inverse association between serum CoQ10 concentrations and the risk for disabling dementia, although serum CoQ10 levels and serum CoQ10/cholesterol ratio did not differ significantly between 65 incident cases and 130 controls.

Finally, Chang et al. [15] reported “low CoQ10 status” in 73% of 80 patients diagnosed with dementia (they used reference values of their laboratory of 0.5-1-7 μM). In addition, they described a correlation between CoQ10 status and values of total antioxidant capacity, MiniMental State Examination, amyloid β-42 (Aβ-42), and Aβ-42/40 ratio, but not with tau protein.

3.2. Studies Assessing Therapeutic Response to CoQ10 Administration in Experimental Models of AD and Other Dementias

The results of studies assessing the response to the administration of COQ10 in different experimental models are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies on the effects of coenzyme Q10 in different experimental models of Alzheimer’s disease.

In general, the administration of CoQ10 alone or in combination with other substances (mainly other antioxidants) has been useful to improve the results of clinical tasks related to learning and memory and to improve or prevent oxidative stress, inflammation and cellular death in different models of AD and frontotemporal dementia including aged rodents [24,25,26,27,28,29], aluminium-induced AD in rats [30,31,32], forebrain lesioned rats [33], intracerebroventricular infusion of Aβ-42 [34] or streptozotocin [37,38] or intrahippocampal injection of Aβ-42 [35,36] in rats, transgenic mice with different mutations inducing AD [39,40,41,43,44,45,46] or frontotemporal dementia [42], and cell cultures using different human [25,45,46,48] or rodent cells [49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. On the other hand, Aβ(1-42) decreased CoQ10 concentrations in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells in culture [47].

3.3. Studies Assessing Therapeutic Response to CoQ10 Administration in Patients with Dementia

3.3.1. Alzheimer’s Disease

Table 3 summarizes the results of the eight eligible studies addressing the therapeutic response to CoQ10 administration in patients with AD [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63], although in one of them, an important percentage of patients included were diagnosed with mixed dementia [61]. Two of these studies used an open-label design [56,61] while the others were randomized clinical trials [33].

Table 3.

Studies describing the effects of COQ10 supplementation in patients with AD. AD: Alzheimer’s disease; ADAS: Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale; ADAS-Cog: ADAS cognitive score; ADAS-Noncog: ADAS non-cognitive scores; ADCS-ADL: Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living; ADL: activities of daily living; CGI-I: clinical global impression improvement; CGI-C: clinical global impression change; CMT: Central macular thickness; DAT: dementia of Alzheimer type; DSS: Digit Symbol Substitution test; GCIPL: Ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer; MMSE: MiniMental State Examination; OCT: optic coherence tomography; RNFL: Retinal nerve fiber layer; SCT: Subfoveal choroidal thickness.

Imagawa et al. [56], after a preliminary report indicating that therapy with CoQ10, iron, and vitamin B6 was effective as mitochondrial activation therapy in 27 AD patients, reported a significant clinical improvement with this therapy in two genetically confirmed AD patients. Three of the randomized clinical trials showed improvement in neuropsychological assessments in patients treated with CoQ10 compared, respectively, with placebo [57,58] or with tacrine [59], while the other two did not show any improvement in comparison with placebo [60,62], although in one of them, the patients treated with CoQ10 showed a better outcome than those treated with a combination of α-tocopherol, vitamin C, and α-lipoic acid [62].

Karakahya and Özcan [63], in a study using optic coherence tomography (OCT), reported an improvement in retinal ganglion cell loss related to AD with short-term topical administration of CoQ10. Finally, an open-label study showed some degree of improvement in the MMSE score and other neuropsychological tests in patients with AD or mixed dementia [61].

3.3.2. Vascular Dementia (VD)

Kawakami et al. [64] measured CSF levels of homovanillic acid (HVA), 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA), 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylethylenglycol (MHPG), and noradrenalin (NA) in six patients with cerebrovascular dementia. CoQ10 administration during 1–2 months returned to normal CSF levels of HVA, 5-HIAA, and MHPG, which had been previously decreased compared to control values.

Qi et al. [65], in a randomized clinical trial involving 88 patients diagnosed with VD (44 of them assigned to treatment with butylphthalide plus idebenone as the observational group, and 44 to idebenone as the control group), showed a higher degree of improvement in MMSE, clinical dementia rating scale (CDRS), and ability of daily life (ADL), and a higher decrease in serum IL6, C reactive protein, TNFα, IL1β, CD31+, CDl44+, and endothelin-1 levels in the observational group compared with the control group.

3.3.3. Mild Cognitive Impairment and Normal Aging

García-Carpintero et al. [66], in a 1-year randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled observational analytical study involving 69 patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) assigned to CoQ10 200 mg/day (n = 33) or placebo (n = 36) showed that although CoQ10 treatment improved cerebral vasoreactivity (assessed by transcranial Doppler sonography) and inflammatory markers, it did not display any significant improvement in the results of an extensive neuropsychological assessment.

Finally, Stough et al. [67] designed a 90-day randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group clinical trial involving 104 healthy subjects aged 60 years and over randomized to either CoQ10 200 mg/day or placebo (52 per group), aiming to evaluate the effects of CoQ10 in the amelioration of cognitive decline that it should be undergoing. Interestingly, a recent study described a significant association of plasma CoQ10 concentrations with cognitive functioning and executive function in elderly people [68].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The possible role of CoQ10 in the pathogenesis of AD and other causes of dementia, if any, is far from established with the current evidence. The studies addressing the serum/plasma levels of CoQ10, which are scarce and based on a relatively small sample size, were similar for AD patients and controls [8,9,10]. The increased values of total and oxidized CoQ10 concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid from patients [11,12] and in certain brain areas from patients with AD [13], described in single studies, have not had further replication studies and await confirmation. Studies on human AD brain are restricted to a single report of a 30–100% increase in CoQ10 concentrations in most of the regions studied (which included the frontal, precentral, temporal and occipital cortex, nucleus caudate, hippocampus, pons, cerebellum, and medulla oblongata) in an unspecified number of AD patients compared with controls [18]. The possibility of induction of aggregates of tau protein and actine by CoQ10 and the finding of the presence of this coenzyme in paired helical filaments and Hirano bodies in the hippocampus [23] lends support to the hypothesis of the possible role of CoQ10 in AD. Studies reporting on CoQ10 concentrations in other causes of dementia are restricted to the measurements in serum/plasma from patients with Lewy body dementia (LBD) [13], vascular dementia [8], and dementia without specification of etiologic diagnosis [14,15].

Because of their antioxidant actions, it was proposed that CoQ10 administration could be a potential protective therapy in AD [69,70]. Moreover, an important number of studies have shown a significant neuroprotective and/or clinical effect of the administration of CoQ10 in different experimental models of AD, as was previously commented in more detail in the Section 3 [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,49,50,51,52,53,54,55] (Table 2). Interestingly, most of the studies performed using cell cultures including human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y [47] and human MC 65 neuroblastoma cells [25], human umbilical vein endothelial cells [48], rat endothelial [49], cortical [50,51] and brain stem cells [52], hippocampal neurons from fetal mice [53], brain mitochondria isolated from aged diabetic rats [54], and rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells [55] have shown a protective effect of CoQ10 on the neurotoxic effects of different types of Aβ. In addition, it has been shown that oral administration of CoQ10 results in an important increase in serum/plasma CoQ10 concentrations in humans [71,72,73] and in rats [73].

The potential beneficial effects of CoQ10 administration, its good absorption, and the lack of important adverse effects led to some initial short-term randomized clinical trials that showed improvement in several neuropsychological tests in patients with AD treated with CoQ10 in comparison with those assigned to placebo [57,58] or the anticholinesterase drug tacrine [59]. However, a further short-term randomized clinical trial failed to determine any benefit except a mild improvement in the ADAS-Cog scores [60].

In conclusion, according to the data from the results presented in this review, there are still important knowledge gaps regarding both the suitability of CoQ10 as a biomarker of AD and other causes of dementia (studies on this issue in brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and other tissues are scarce) and the possible usefulness of treatment with CoQ10 in patients with AD (controversial results of randomized controlled trials with a maximum of 1 year of follow-up) despite the promising neuroprotective effects of CoQ10 detected in different models of AD. The design of further studies with a longer-term follow-up period is needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antiox12020533/s1, Table S1: PRISMA Checklist; Table S2: MOOSE Checklist.

Author Contributions

F.J.J.-J.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Project administration. H.A.-N.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Project administration. E.G.-M.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Project administration, Obtaining funding. J.A.G.A.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Project administration, Obtaining funding. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work at the authors’ laboratory is supported in part by Grants PI18/00540 and PI21/01683 from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain, and IB20134 and GR21073 from Junta de Extremadura, Mérida, Spain. Partially funded with FEDER funds.

Acknowledgments

We thank James McCue for assistance with the English language. We also appreciate the efforts of the personnel of the Library of Hospital Universitario del Sureste, Arganda del Rey, who retrieved an important number of papers for us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Crane, F.L. Biochemical functions of coenzyme Q10. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2001, 20, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantle, D.; Heaton, R.A.; Hargreaves, I.P. Coenzyme Q10, Ageing and the Nervous System: An Overview. Antioxidants 2021, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, F.J.; Alonso-Navarro, H.; Ayuso-Peralta, L.; Jabbour-Wadih, T. Estrés oxidativo y enfermedad de Alzheimer. Rev. Neurol. 2006, 42, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumaran, K.R.; Yunusa, S.; Perimal, E.; Wahab, H.; Müller, C.P.; Hassan, Z. Insights into the Pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s Disease and Potential Therapeutic Targets: A Current Perspective. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 91, 507–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurcau, A. Insights into the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases, Focus on Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality If Nonrandomized Studies in Meta Analyses. Available online: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- de Bustos, F.; Molina, J.A.; Jiménez-Jiménez, F.J.; García-Redondo, A.; Gómez-Escalonilla, C.; Porta-Etessam, J.; Berbel, A.; Zurdo, M.; Barcenilla, B.; Parrilla, G.; et al. Serum levels of coenzyme Q10 in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neural. Transm. 2000, 107, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battino, M.; Bompadre, S.; Leone, L.; Devecchi, E.; Degiuli, A.; D’Agostino, F.; Cambiè, G.; D’Agostino, M.; Faggi, L.; Colturani, G.; et al. Coenzyme Q, Vitamin E and Apo-E alleles in Alzheimer Disease. Biofactors 2003, 18, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giavarotti, L.; Simon, K.A.; Azzalis, L.A.; Fonseca, F.L.; Lima, A.F.; Freitas, M.C.; Brunialti, M.K.; Salomão, R.; Moscardi, A.A.; Montaño, M.B.; et al. Mild systemic oxidative stress in the subclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 2013, 609019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, C.; Abe, T.; Terayama, Y. Increase in the oxidized/total coenzyme Q-10 ratio in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2009, 28, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, C.; Abe, T.; Terayama, Y. Levels of reduced and oxidized coenzyme Q-10 and 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine in the CSF of patients with Alzheimer’s disease demonstrate that mitochondrial oxidative damage and/or oxidative DNA damage contributes to the neurodegenerative process. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina, J.A.; de Bustos, F.; Ortiz, S.; Del Ser, T.; Seijo, M.; Benito-Léon, J.; Oliva, J.M.; Pérez, S.; Manzanares, J. Serum levels of coenzyme Q in patients with Lewy body disease. J. Neural. Transm. 2002, 109, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, K.; Ikeda, A.; Moriyama, Y.; Chei, C.L.; Noda, H.; Umesawa, M.; Cui, R.; Nagao, M.; Kitamura, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. Serum coenzyme Q10 and risk of disabling dementia, the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Atherosclerosis 2014, 237, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.S.; Chou, H.H.; Lai, T.J.; Yen, C.H.; Pan, J.C.; Lin, P.T. Investigation of coenzyme Q10 status.; serum amyloid-β.; and tau protein in patients with dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 910289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduzzi, S.; Rücker, G.; Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: A practical tutorial. BMJ Ment. Health 2019, 22, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2009, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der Simonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, D. Confidence intervals for the between-study variance in random effects meta-analysis using generalised Cochran heterogeneity statistics. Res. Synth. Methods 2013, 4, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedges, L.V. Meta-Analysis. J. Educ. Stat. 1992, 17, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlund, C.; Söderberg, M.; Kristensson, K.; Dallner, G. Ubiquinone, dolichol, and cholesterol metabolism in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 1992, 70, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Vlkolinsky, R.; Cairns, N.; Fountoulakis, M.; Lubec, G. The reduction of NADH ubiquinone oxidoreductase 24- and 75-kDa subunits in brains of patients with Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci. 2001, 68, 2741–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Mara, I.; Santpere, G.; MacDonald, M.J.; Gomez de Barreda, E.; Hernandez, F.; Moreno, F.J.; Ferrer, I.; Avila, J. Coenzyme q induces tau aggregation.; tau filaments.; and Hirano bodies. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 67, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.R.; Sohal, R.S.; Forster, M.J. Concurrent administration of coenzyme Q10 and alpha-tocopherol improves learning in aged mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 38, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadsworth, T.L.; Bishop, J.A.; Pappu, A.S.; Woltjer, R.L.; Quinn, J.F. Evaluation of coenzyme Q as an antioxidant strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2008, 14, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sumien, N.; Heinrich, K.R.; Shetty, R.A.; Sohal, R.S.; Forster, M.J. Prolonged intake of coenzyme Q10 impairs cognitive functions in mice. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1926–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, R.A.; Forster, M.J.; Sumien, N. Coenzyme Q(10) supplementation reverses age-related impairments in spatial learning and lowers protein oxidation. Age 2013, 35, 1821–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, R.A.; Ikonne, U.S.; Forster, M.J.; Sumien, N. Coenzyme Q10 and α-tocopherol reversed age-associated functional impairments in mice. Exp. Gerontol. 2014, 58, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim Fouad, G. Combination of Omega 3 and Coenzyme Q10 Exerts Neuroprotective Potential against Hypercholesterolemia-Induced Alzheimer’s-Like Disease in Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 1142–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Abo El-Ella, D.M.; El-Emam, S.Z.; Shahat, A.S.; El-Sayed, R.M. Physical & mental activities enhance the neuroprotective effect of vinpocetine & coenzyme Q10 combination against Alzheimer & bone remodeling in rats. Life Sci. 2019, 229, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, H.; Albuhayri, S.; Alaraidh, S.; Alotaibi, A.; Yacoub, H.; Mohamad, R.; Al-Amin, M. Biotin, coenzyme Q10, and their combination ameliorate aluminium chloride-induced Alzheimer’s disease via attenuating neuroinflammation and improving brain insulin signaling. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2020, 34, e22519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Khalil, M.G.; Abd El-Latif, D.M.; Okda, T.; Abdelaziz, A.I.; Abu-Elfotuh, K.; Kamal, M.M.; Wahid, A. The influence of vinpocetine alone or in combination with Epigallocatechin-3-gallate, Coenzyme COQ10, Vitamin E and Selenium as a potential neuroprotective combination against aluminium-induced Alzheimer’s disease in Wistar Albino Rats. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2022, 98, 104557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitta, A.; Murakami, Y.; Furukawa, Y.; Kawatsura, W.; Hayashi, K.; Yamada, K.; Hasegawa, T.; Nabeshima, T. Oral administration of idebenone induces nerve growth factor in the brain and improves learning and memory in basal forebrain-lesioned rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1994, 349, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Tanaka, T.; Han, D.; Senzaki, K.; Kameyama, T.; Nabeshima, T. Protective effects of idebenone and alpha-tocopherol on beta-amyloid-(1-42)-induced learning and memory deficits in rats: Implication of oxidative stress in beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, A. Microglial Inhibitory Mechanism of Coenzyme Q10 Against Aβ (1-42) Induced Cognitive Dysfunctions: Possible Behavioral, Biochemical, Cellular, and Histopathological Alterations. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaki, H.; Faraji, N.; Komaki, A.; Shahidi, S.; Etaee, F.; Raoufi, S.; Mirzaei, F. Investigation of protective effects of coenzyme Q10 on impaired synaptic plasticity in a male rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2019, 147, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishrat, T.; Khan, M.B.; Hoda, M.N.; Yousuf, S.; Ahmad, M.; Ansari, M.A.; Ahmad, A.S.; Islam, F. Coenzyme Q10 modulates cognitive impairment against intracerebroventricular injection of streptozotocin in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2006, 171, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheykhhasan, M.; Amini, R.; Soleimani Asl, S.; Saidijam, M.; Hashemi, S.M.; Najafi, R. Neuroprotective effects of coenzyme Q10-loaded exosomes obtained from adipose-derived stem cells in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 152, 113224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Li, G.; Wang, J.; Yang, E.S. Coenzyme Q10 attenuates beta-amyloid pathology in the aged transgenic mice with Alzheimer presenilin 1 mutation. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2008, 34, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Dai, G.; Li, G.; Yang, E.S. Coenzyme Q10 reduces beta-amyloid plaque in an APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2010, 41, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, M.; Kipiani, K.; Yu, F.; Wille, E.; Katz, M.; Calingasan, N.Y.; Gorras, G.K.; Lin, M.T.; Beal, M.F. Coenzyme Q10 decreases amyloid pathology and improves behavior in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 27, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elipenahli, C.; Snack, C.; Jainuddin, S.; Gerges, M.; Yang, L.; Starkov, A.; Beal, M.F.; Dumont, M. Behavioral improvement after chronic administration of coenzyme Q10 in P301S transgenic mice. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2012, 28, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumaran, K.; Kanwar, A.; Vegh, C.; Marginean, A.; Elliott, A.; Guilbeault, N.; Badour, A.; Sikorska, M.; Cohen, J.; Pandey, S. Ubisol-Q10 (a Nanomicellar Water-Soluble Formulation of CoQ10) Treatment Inhibits Alzheimer-Type Behavioral and Pathological Symptoms in a Double Transgenic Mouse (TgAPEswe.; PSEN1dE9) Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 61, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Ren, X.; Huang, P.; Li, S.; Ma, Q.; Ying, M.; Ni, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, X. Proteomic analysis of serum proteins in triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice: Implications for identifying biomarkers for use to screen potential candidate therapeutic drugs for early Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014, 40, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.; Stokes, K.; Mahngar, K.; Domazet-Damjanov, D.; Sikorska, M.; Pandey, S. Inhibition of stress induced premature senescence in presenilin-1 mutated cells with water soluble Coenzyme Q10. Mitochondrion 2014, 17, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegh, C.; Pupulin, S.; Wear, D.; Culmone, L.; Huggard, R.; Ma, D.; Pandey, S. Resumption of Autophagy by Ubisol-Q10 in Presenilin-1 Mutated Fibroblasts and Transgenic AD Mice, Implications for Inhibition of Senescence and Neuroprotection. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 7404815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.L.; Xiu, J.; Shan, K.R.; Xiao, Y.; Gu, R.; Liu, R.Y.; Guan, Z.Z. Oxidative stress induced by beta-amyloid peptide(1-42) is involved in the altered composition of cellular membrane lipids and the decreased expression of nicotinic receptors in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Neurochem. Int. 2005, 46, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durán-Prado, M.; Frontiñán, J.; Santiago-Mora, R.; Peinado, J.R.; Parrado-Fernández, C.; Gómez-Almagro, M.V.; Moreno, M.; López-Domínguez, J.A.; Villalba, J.M.; Alcaín, F.J. Coenzyme Q10 protects human endothelial cells from β-amyloid uptake and oxidative stress-induced injury. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frontiñán-Rubio, J.; Rabanal-Ruiz, Y.; Durán-Prado, M.; Alcain, F.J. The Protective Effect of Ubiquinone against the Amyloid Peptide in Endothelial Cells Is Isoprenoid Chain Length-Dependent. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Park, H.H.; Koh, S.H.; Choi, N.Y.; Yu, H.J.; Park, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, K.Y. Coenzyme Q10 protects against amyloid beta-induced neuronal cell death by inhibiting oxidative stress and activating the P13K pathway. Neurotoxicology 2012, 33, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, L.; Jia, K.; Wang, Q.; Sui, S.; Lin, Y.; He, Y. Idebenone protects mitochondrial function against amyloid beta toxicity in primary cultured cortical neurons. Neuroreport 2020, 31, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Park, H.H.; Lee, K.Y.; Choi, N.Y.; Yu, H.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, J.; Huh, Y.M.; Lee, S.H.; Koh, S.H. Coenzyme Q10 restores amyloid beta-inhibited proliferation of neural stem cells by activating the PI3K pathway. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 2112–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Lian, N.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, K.; Yu, Y. Coenzyme Q10 alleviates sevoflurane-induced neuroinflammation by regulating the levels of apolipoprotein E and phosphorylated tau protein in mouse hippocampal neurons. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, P.I.; Santos, M.S.; Sena, C.; Nunes, E.; Seiça, R.; Oliveira, C.R. CoQ10 therapy attenuates amyloid beta-peptide toxicity in brain mitochondria isolated from aged diabetic rats. Exp. Neurol. 2005, 196, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Xu, D.; Lin, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, G.; Sui, L.; Ding, H.; Du, J. Coenzyme Q10 attenuated β-amyloid25-35-induced inflammatory responses in PC12 cells through regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Brain Res Bull. 2017, 131, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imagawa, M.; Naruse, S.; Tsuji, S.; Fujioka, A.; Yamaguchi, H. Coenzyme Q10.; iron.; and vitamin B6 in genetically-confirmed Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 1992, 340, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyer, G.; Babej-Dölle, R.M.; Hadler, D.; Hofmann, S.; Herrmann, W.M. A controlled study of 2 doses of idebenone in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychobiology 1997, 36, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutzmann, H.; Hadler, D. Sustained efficacy and safety of idebenone in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: Update on a 2-year double-blind multicentre study. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 1998, 54, 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Gutzmann, H.; Kühl, K.P.; Hadler, D.; Rapp, M.A. Safety and efficacy of idebenone versus tacrine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Results of a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group multicenter study. Pharmacopsychiatry 2002, 35, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, L.J.; Grundman, M.; Berg, J.; Ernstrom, K.; Margolin, R.; Pfeiffer, E.; Weiner, M.F.; Zamrini, E.; Thomas, R.G. Idebenone treatment fails to slow cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2003, 61, 1498–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronkova, K.V.; Meleshkov, M.N. Use of Noben (idebenone) in the treatment of dementia and memory impairments without dementia. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2009, 39, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasko, D.R.; Peskind, E.; Clark, C.M.; Quinn, J.F.; Ringman, J.M.; Jicha, G.A.; Cotman, C.; Cottrell, B.; Montine, T.J.; Thomas, R.G.; et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Antioxidants for Alzheimer disease: A randomized clinical trial with cerebrospinal fluid biomarker measures. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 836–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakahya, R.H.; Özcan, T.Ş. Salvage of the retinal ganglion cells in transition phase in Alzheimer’s disease with topical coenzyme Q10, is it possible? Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020, 258, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, M.; Itoh, T. Effects of idebenone on monoamine metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with cerebrovascular dementia. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 1989, 8, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.X.; Hu, Y.; Kang, L.J.; Li, P.; Gao, T.C.; Zhang, X. Effects of Butyphthalide Combined with Idebenone on Inflammatory Cytokines and Vascular Endothelial Functions of Patients with Vascular Dementia. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2020, 30, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carpintero, S.; Domínguez-Bértalo, J.; Pedrero-Prieto, C.; Frontiñán-Rubio, J.; Amo-Salas, M.; Durán-Prado, M.; García-Pérez, E.; Vaamonde, J.; Alcain, F.J. Ubiquinol Supplementation Improves Gender-Dependent Cerebral Vasoreactivity and Ameliorates Chronic Inflammation and Endothelial Dysfunction in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stough, C.; Nankivell, M.; Camfield, D.A.; Perry, N.L.; Pipingas, A.; Macpherson, H.; Wesnes, K.; Ou, R.; Hare, D.; de Haan, J.; et al. CoQ10 and Cognition a Review and Study Protocol for a 90-Day Randomized Controlled Trial Investigating the Cognitive Effects of Ubiquinol in the Healthy Elderly. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Portero, C.; Amián, J.G.; Bella, R.; López-Lluch, G.; Alarcón, D. Coenzyme Q10 Levels Associated with Cognitive Functioning and Executive Function in Older Adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2023, 78, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundman, M.; Grundman, M.; Delaney, P. Antioxidant strategies for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2002, 61, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases and coenzyme Q10 as a potential treatment. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2004, 36, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnrot, K.; Metsä-Ketelä, T.; Molnár, G.; Ahonen, J.P.; Latvala, M.; Peltola, J.; Pietilä, T.; Alho, H. The effect of ascorbate and ubiquinone supplementation on plasma and CSF total antioxidant capacity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 21, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shults, C.W.; Flint Beal, M.; Song, D.; Fontaine, D. Pilot trial of high dosages of coenzyme Q10 in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2004, 188, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nukui, K.; Yamagishi, T.; Miyawaki, H.; Kettawan, A.; Okamoto, T.; Belardinelli, R.; Tiano, L.; Littarru, G.P.; Sato, K. Blood CoQ10 levels and safety profile after single-dose or chronic administration of PureSorb-Q40, animal and human studies. Biofactors 2008, 32, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).