Opposing Morphogenetic Defects on Dendrites and Mossy Fibers of Dentate Granular Neurons in CRMP3-Deficient Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mouse Breeding and Genotyping

2.2. Golgi and X-gal Staining

2.3. Timm Staining

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

2.5. Neurite and Infrapyramidal Bundle (IPB) Length Quantification

2.6. Statistics

3. Results

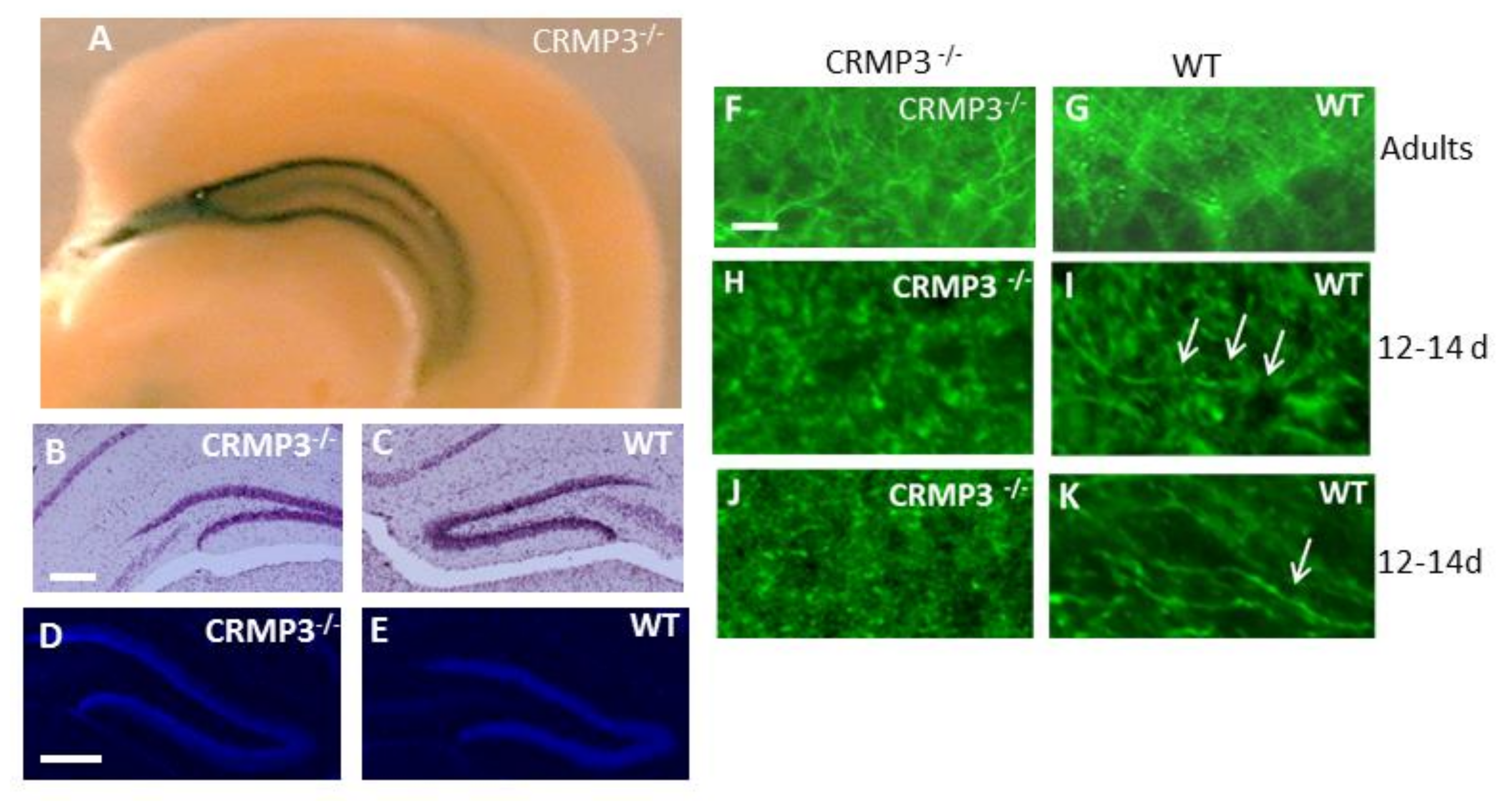

3.1. Collapsin Response Mediator Protein 3 (CRMP3)−/− Dentate Gyrus

3.2. Dystrophy of Dendrites in CRMP3−/− Granular Neurons

3.3. Dendritic Spine Alterations in CRMP3−/− Granular Neurons

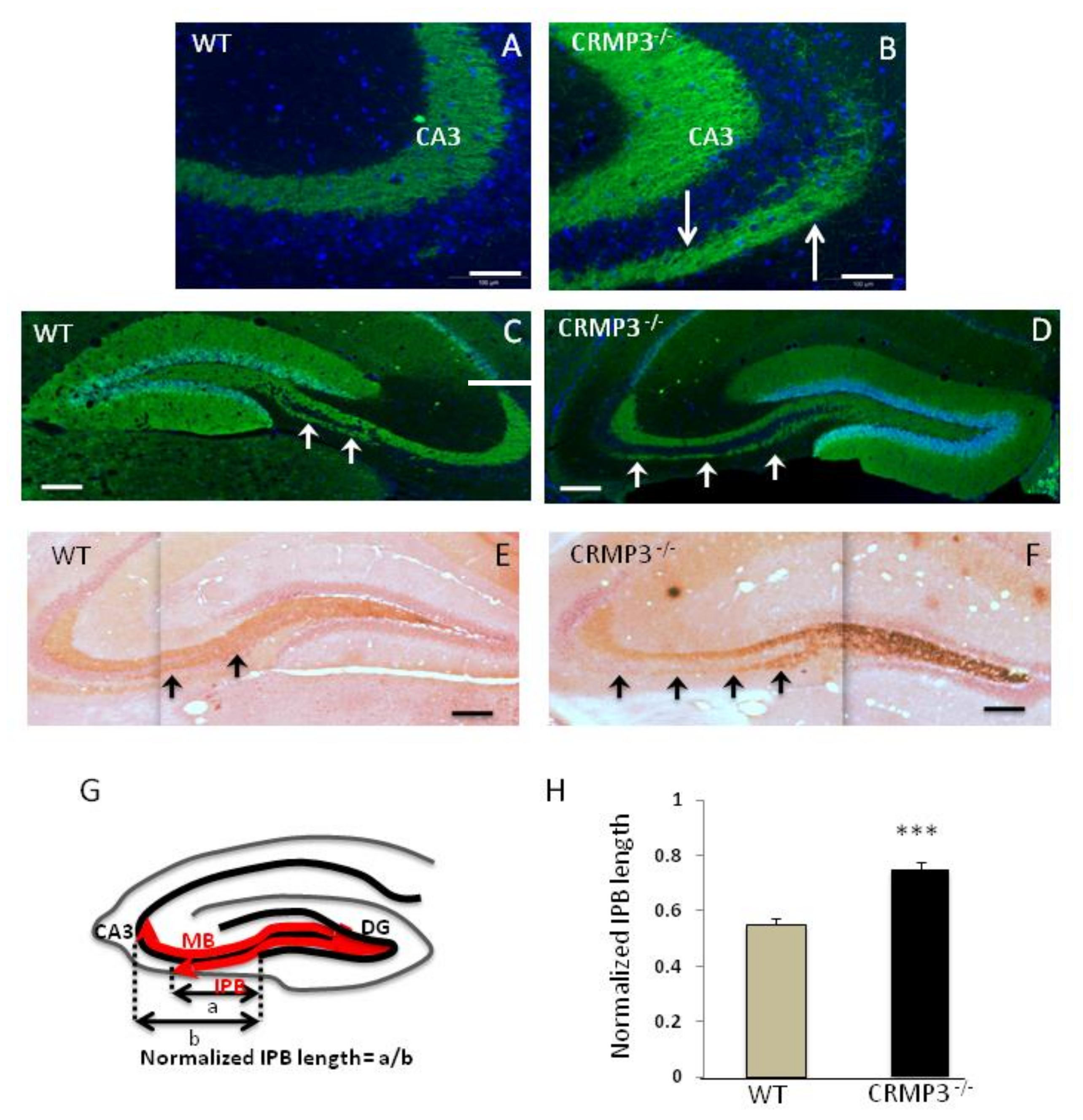

3.4. Mossy Fiber Outgrowth in CRMP3−/− Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| CRMP3 expression in 5-week old mice | |

|---|---|

| CA1; CA3 | +++ |

| Dentate Gyrus | +++++ |

| Cerebellum (Granular Cells) | + |

| Thalamus | ++ |

| Hypothalamus | + |

| Pons (Olivary Complex) | +++ |

| Reticular Formation | + |

| Cortex, Striatum | ND |

| Spinal Cord | ND/* |

| Dorsal Root Ganglia | ND/* |

Appendix B

| Accession Number | Gene Description | Direction of Change (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decrease | Increase | ||

| M86567 | GABA-A receptor, subunit alpha2 | −32 | |

| M64068 | Zinc Finger Protein (bmi-1) | −34 | |

| AF033003 | K+ channel beta-1 subunit (KVB1) | −36 | |

| M37335 | Myelin proteolipid protein | −38 | |

| HO5479 | Calcineurin catalytic subunit | −39 | |

| M21041 | MAP2 | −41 | |

| X51396 | Map5 | −42 | |

| U34973 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase-like | −46 | |

| AB022342 | Glutamate receptor channel, subunit α3 | −51 | |

| U42384 | FGF inducible 15 | −56 | |

| X57498 | Glutamate receptor AMPA2, subunit α2 | −70 | |

| X61430 | GABA-A receptor, subunit α1 | −72 | |

| X84234 | Ganglioside GM 1 | +152 | |

| AF037437 | Prosaposin | +166 | |

| X76858 | E4F transcription factor | +218 | |

| X95518 | neuronal tyrosine/threonine phosphatase 1 | +226 | |

| X72305 | Corticotropin releasing hormone receptor | +248 | |

Appendix C

References

- Lee, J.W.; Jung, M.W. Separation or binding? Role of the dentate gyrus in hippocampal mnemonic processing. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 75, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakahara, S.; Adachi, M.; Ito, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Tajinda, K.; Van Erp, T.G.M. Hippocampal Pathophysiology: Commonality Shared by Temporal Lobe Epilepsy and Psychiatric Disorders. Neurosci. J. 2018, 22, 4852359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, H.A.; Schoenfeld, T.J. Behavioral and structural adaptations to stress. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 4, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesner, R.P. An analysis of dentate gyrus function (an update). Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 354, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, C.; Engelhardt, M. Anatomy of the hippocampal formation. Front. Neurol. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauder, J.M.; Mugnaini, E. Infrapyramidal mossy fibers in the hippocampus of the hyperthyroid rat. A light and electron microscopy study. Dev. Neurosci. 1980, 3, 248–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccomagno, M.M.; Kolodkin, A.L. Sculpting neural circuits by axon and dendrite pruning. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 31, 779–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuldiner, O.; Yaron, A. Mechanisms of developmental neurite pruning. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledda, F.; Paratcha, G. Mechanisms regulating dendritic arbor patterning. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 4511–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puram, S.V.; Bonni, A. Cell-intrinsic drivers of dendrite morphogenesis. Development 2013, 140, 4657–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copf, T. Importance of gene dosage in controlling dendritic arbor formation during development. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2015, 42, 2234–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, R.; Ikegaya, Y. The Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Axon Guidance in Mossy Fiber Sprouting. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, T.T.; Lerch, J.K.; Honnorat, J.; Khanna, R.; Duchemin, A.M. Neuronal networks in mental diseases and neuropathic pain: Beyond brain derived neurotrophic factor and collapsin response mediator proteins. World J. Psychiatry 2016, 6, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, J.; Baba, R.; Ohshima, T. CRMPs Function in Neurons and Glial Cells: Potential Therapeutic Targets for Neurodegenerative Diseases and CNS Injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 4243–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, T.T.; Massicote, G.; Belin, M.F.; Honnorat, J.; Glasper, E.R.; Devries, A.C.; Jakeman, L.; Baudry, M.; Duchemin, A.M.; Kolattukudy, P.E. CRMP3 is required for hippocampal CA1 dendritic organization and plasticity. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demyanenko, G.K.; Tsai, A.Y.; Maness, P.F. Abnormalities in neuronal process extension, hippocampal development, and the ventricular system of L1 knockout mice. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 4907–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timm, F. Zur histochemie der Schwermetalle. Das Sulfid-Silber-verfahren. Disch. Z. Ges. Gerichtl. Med. 1958, 46, 706–711. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Slomianka, L. Neurons of origin of zinc-containing pathways and the distribution of zinc-containing bouton in the hippocampal region of the rat. Neuroscience 1992, 48, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, T.T.; Wilson, S.M.; Rogemond, V.; Chounlamountri, N.; Kolattukudy, P.E.; Martinez, S.; Khanna, M.; Belin, M.F.; Khanna, R.; Honnorat, J.; et al. Mapping CRMP3 domains involved in dendrite morphogenesis and voltage-gated calcium channel regulation. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 4262–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagri, A.; Cheng, H.J.; Yaron, A.; Pleasure, S.J.; Tessier-Lavigne, M. Stereotyped pruning of long hippocampal axon branches by retraction inducers of the semaphorin family. Cell 2003, 113, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, T.T.; Mosinger, B.; Ricard, D.; Copeland, N.C.; Gilbert, D.J.; Jenkins, J.A.; Stankford, B.; Honnorat, J.; Belin, M.F.; Kolattukudy, P.E. Collapsin response mediator protein 3/unc33-like protein 4 gene: Organization, chromosomal mapping and expression in the developing mouse brain. Gene 2000, 242, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloviter, R.S. Calbindin and parvalbumin immunocytolocalization in the rat hippocampus with specific reference to the specific vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to seizure activity. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989, 280, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, T.T.; Honnorat, J.; Kolattukudy, P.E.; Khanna, R.; Duchemin, A.M. CRMPs: Critical molecules for neurite morphogenesis and neuropsychiatric diseases. Mol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, T.T.; Wang, Y.; Khanna, R.; Chounlamountri, N.; Auvergnon, N.; Honnorat, J.; Duchemin, A.M. Effect of CRMP3 expression on dystrophic dendrites of hippocampal neurons. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, D.; Caudy, M. Pioneer axons lose directed growth after selective killing of guidepost cells. Nature 1983, 304, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, T.P.; Bentley, J.S. Accumulation of actin in subsets of pioneer growth cone filopodia in response to neural and epithelial guidance cues in situ. J. Cell. Biol. 1990, 123, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.B.; Schmidt, M.F.; Kater, S.B. Laminin and fibronectin guideposts signal sustained but opposite effects to passing growth cones. Neuron 1995, 14, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A.; Nawabi, F.; Moret, F.; Yaron, A.; Weaver, E.; Bozon, M.; Abouzid, K.; Guan, J.L.; Tessier-Lavigne, M.; Lemmon, V.; et al. FAK-MAPK-dependent adhesion disassembly downstream of L1 contributes to semaphorin 3A-induced collapse. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 1549–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, K.P.; Nedivi, E. Spine Dynamics: Are They All the Same? Neuron 2017, 96, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahay, A.; Molliver, M.E.; Ginty, D.D.; Kolodkin, A.L. Semaphorin 3F is critical for development of limbic system circuitry and is required in neurons for selective CNS axon guidance events. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 6671–6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Bagri, A.; Zupicich, J.A.; Zou, Y.; Stoeckli, E.; Pleasure, S.J.; Lowenstein, D.H.; Skarmes, W.C.; Chedotal, A.; Tessier-Lavigne, M. Neuropilin-2 regulates the development of select cranial and sensory nerves and hippocampal mossy fiber projections. Neuron 2000, 25, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Bagri, A.; Yaron, A.; Stein, E.; Pleasure, S.J.; Tessier-Lavigne, M. Plexin-3A mediates semaphorin signaling and regulates the development of hippocampal axonal projection. Neuron 2001, 32, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Dai, F.R.; Du, X.P.; Yang, Q.D.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. Infusion of BDNF into the nucleus accumbens of aged rats improves cognition and structural synaptic plasticity through PI3K-ILK-AKt signaling. Behav. Brain Res. 2012, 231, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Languren, L.E.; Escobar, M.L. Plasticity and metaplasticity of adult rat hippocampus mossy fibers induced by neurotrophin-3. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2013, 37, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, T.T.; Glasper, E.R.; Devries, C.; Honnorat, J.; Kolattukudy, P.E.; Duchemin, A.M. Altered prepulse inhibition in mice with dendrite abnormalities of hippocampal neurons. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008, 13, 656–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepan, J.; Hladky, F.; Uribe, A.; Holsboer, F.; Schmidt, M.V.; Eder, M. High-Speed imaging reveals opposing effects of chronic stress and antidepressants on neuronal activity propagation through the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit. Front. Neural Circuits 2015, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benes, F.M. Evidence for altered trisynaptic circuitry in schizophrenic hippocampus. Bio. Psychiatry. 1999, 46, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthi, P.; Premkumar, P.; Priyanka, R.; Jayachandran, K.S.; Anusuyadevi, M. Pathological changes in hippocampal neuronal circuits underlie age-associated neurodegeneration and memory loss: Positive clue toward SAD. Neuroscience 2015, 301, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quach, T.T.; Auvergnon, N.; Khanna, R.; Belin, M.-F.; Kolattukudy, P.E.; Honnorat, J.; Duchemin, A.-M. Opposing Morphogenetic Defects on Dendrites and Mossy Fibers of Dentate Granular Neurons in CRMP3-Deficient Mice. Brain Sci. 2018, 8, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8110196

Quach TT, Auvergnon N, Khanna R, Belin M-F, Kolattukudy PE, Honnorat J, Duchemin A-M. Opposing Morphogenetic Defects on Dendrites and Mossy Fibers of Dentate Granular Neurons in CRMP3-Deficient Mice. Brain Sciences. 2018; 8(11):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8110196

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuach, Tam T., Nathalie Auvergnon, Rajesh Khanna, Marie-Françoise Belin, Papachan E. Kolattukudy, Jérome Honnorat, and Anne-Marie Duchemin. 2018. "Opposing Morphogenetic Defects on Dendrites and Mossy Fibers of Dentate Granular Neurons in CRMP3-Deficient Mice" Brain Sciences 8, no. 11: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8110196

APA StyleQuach, T. T., Auvergnon, N., Khanna, R., Belin, M.-F., Kolattukudy, P. E., Honnorat, J., & Duchemin, A.-M. (2018). Opposing Morphogenetic Defects on Dendrites and Mossy Fibers of Dentate Granular Neurons in CRMP3-Deficient Mice. Brain Sciences, 8(11), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8110196