Why the Brain Knows More than We Do: Non-Conscious Representations and Their Role in the Construction of Conscious Experience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Non-Conscious Perception Influencing Conscious Cognition and Action

3. The Functional Role of Non-Conscious Representation

3.1. Adaptive Resonance and Brain Learning

3.2. Non-Conscious Representation Matching

- (1)

- Bottom-Up Automatic Activation is a mechanism for the processing and the temporary storage of perceptual input outside conscious experience. Through Bottom-Up Automatic Activation, a group of cells within a given neural structure becomes supraliminally active whenever it receives the necessary bottom-up signals. These bottom-up signals may or may not be consciously experienced. They are then multiplied by adaptive weights that represent long-term memory traces and influence the activation of cells at a higher processing level. Grossberg [14] originally proposed Bottom-Up Automatic Activation to account for the way in which pre-attentive processes generate learning in the absence of top-down attention or expectation. It appears that this mechanism is equally well suited to explain how subliminal signals may trigger supraliminal neural activities in the absence of phenomenal awareness. Bottom-Up Automatic Activation generating supraliminal brain signals, or representations with adaptive weights near or at zero, would be a candidate mechanism to explain how the brain manages to process perceptual input that is either not relevant at a given moment in time, or cannot be made available to conscious processing because of a lesion in the circuitry, as in vision without consciousness for example.

- (2)

- Top-down Representation Matching is a mechanism for selectively matching bottom-up representations of incoming signals to learnt memory representations. Subliminal representations may become supraliminal when bottom-up signals or representations are sufficiently relevant at a given moment in time to activate statistically significant matching signals. These would then temporally match the bottom-up representations (coincidence). A positive match confirms and amplifies ongoing bottom-up representation, whereas a negative match tends to invalidate ongoing bottom-up representation [14]. Top-down matching thus may be conceived as a selective process where non-conscious representations become either embedded in, or remain temporarily inaccessible to, conscious experience.

4. How Does the Brain Link Non-Conscious Representations to Generate Conscious Experience?

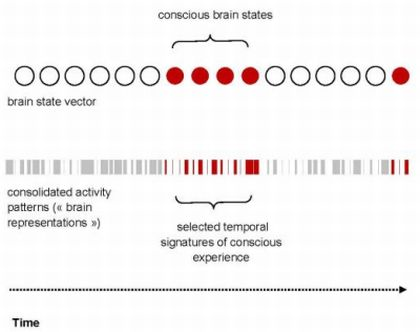

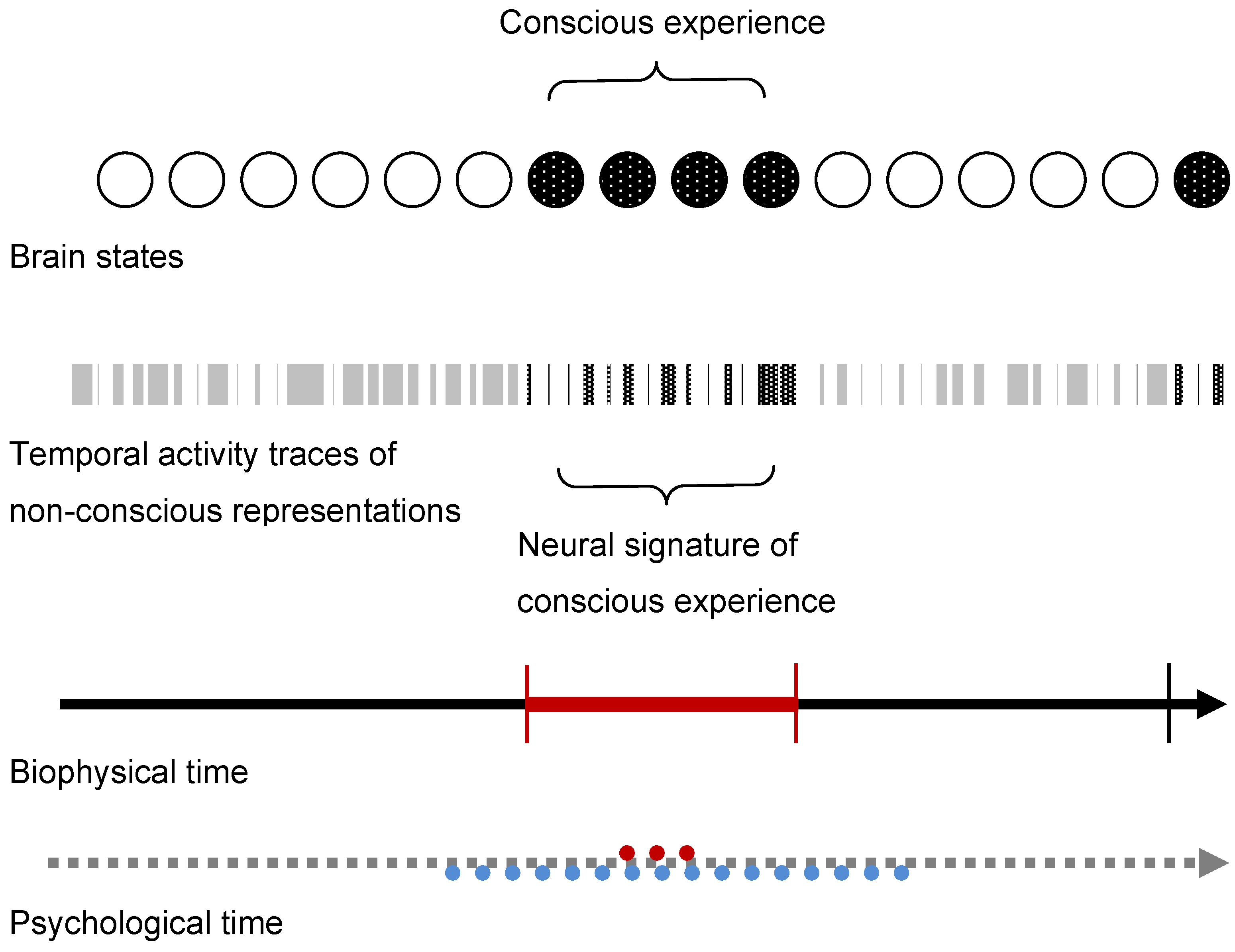

4.1. The Temporal Signatures of Conscious Experience

4.2. Functional Implications of Long-Distance Reentrant Signaling

4.3. Cortical Plasticity and Epigenetic Factors

5. Conclusions

References

- Piaget, J. La Construction du Réel Chez L’enfant; Delachaux et Niestlé: Neuchätel, Switerland, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bulf, H.; Johnson, S.P.; Valenza, E. Visual statistical learning in the newborn infant. Cognition 2011, 121, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes, J. The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind; Houghton-Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, G.M. Neural Darwinism: Selection and reentrant signaling in higher brain function. Neuron 1993, 10, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smythies, J. Space, time and consciousness. J. Cons. Stud. 2003, 10, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kihlstrom, J.F. The cognitive unconscious. Science 1987, 237, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Dehaene, S.; Changeux, J.P.; Nacchache, L.; Sackur, J.; Sergent, C. Conscious, preconscious and subliminal processing: A testable taxonomy. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006, 10, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, M. Social cognitive neuroscience: A review of core processes. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 259–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiffrin, R.M. Attention, Automatism, and Consciousness. In Essential Sources in the Scientific Study of Consciousness; Baars, B.J., Banks, W.P., Newman, J.B., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 631–642. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, O.; Lisman, J.E. Novel lists of 7 ± 2 known items can be reliably stored in an oscillatory short-term memory network: Interaction with long-term memory. Learn. Mem. 1996, 3, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossberg, S. How hallucinations may arise from brain mechanisms of learning, attention, and volition. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2000, 6, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.R. The neurophysics of consciousness. Brain Res. Rev. 2002, 39, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp-Langley, B.; Durup, J. Plastic temporal code for conscious state generation in the brain. Neural Plast. 2009, 2009, 482696:1–482696:15. [Google Scholar]

- Grossberg, S. How does the cerebral cortex work? Learning, attention, and grouping by the laminar circuits of visual cortex. Spat. Vis. 1999, 12, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helekar, S.A. On the possibility of universal neural coding of subjective experience. Conscious. Cogn. 1999, 8, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libet, B. Mind Time; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, L. The Subliminal Psychodynamic Activation Method: Overview and Comprehensive Listing of Studies. In Empirical Studies in Psychoanalytic Theories; Masling, J., Ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1983; Volume 1, pp. 69–100. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, L.; Weinberger, J. Mommy and I are one: Implications for psychotherapy. Am. Psychol. 1985, 40, 1296–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.I.; Igleheart, H.C.; Silverman, L.H. Subliminal stimulation of symbiotic fantasies as an aid in the treatment of drug abusers. Int. J. Addict. 1987, 22, 751–765. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, R.F. Critical importance of stimulus unawareness for the production of subliminal psychodynamic activation effects: A meta-analytic review. J. Clin. Psychol. 1990, 46, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, R.F. Critical importance of stimulus unawareness for the production of subliminal psychodynamic activation effects: An attributional model. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1992, 180, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaloult, L.; Borgeat, F.; Elie, R. Use of subconscious and conscious suggestions combined with music as a relaxation technique. Can. J. Psychiatry 1988, 33, 734–740. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, R. Reply to Greenberg’s critique of Malik et al.’s experiment on the method of subliminal psychodynamic activation. Percept. Mot. Skills 1998, 87, 313–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Paraherakis, A.; Joseph, S.; Ladd, H. The method of subliminal psychodynamic activation: Do individual thresholds make a difference? Percept. Mot. Skills 1996, 83, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Paraherakis, A. How limited is the unconscious? A brief commentary. Percept. Mot. Skills 1998, 86, 345–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, A.C. Further comments regarding Malik et al.’s experiment on the method of subliminal psychodynamic activation. Percept. Mot. Skills 1998, 87, 1369–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardaway, R.A. Subliminally activated symbiotic fantasies: Facts and artifacts. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, J.F. State of the “state” debate in hypnosis: A view from the cognitive-behavioral perspective. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 1997, 45, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, K.S. The Waterloo-Stanford Group (WSGC) scale of hypnotic suggestibility: Normative and comparative data. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 1993, 41, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, K.S. Waterloo-Stanford Group Scale of Hypnotic suggestibility, Form C: Manual and response booklet. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 1998, 46, 250–268. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, F.; Persinger, M.A.; Koren, S.A. Enhanced hypnotic suggestibility following application of burst-firing magnetic fields over the right temporoparietal lobes: A replication. Int. J. Neurosci. 1996, 87, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainville, P.; Carrier, B.; Hofbauer, R.K.; Bushnell, M.C.; Duncan, G.H. Dissociation of pain sensory and affective dimensions using hypnotic modulation. Pain 1999, 82, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szechtman, H.; Woody, E.; Bowers, K.S.; Nahmias, C. Where the imaginal appears real: A positron emission tomography study of auditory hallucinations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 1956–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, J.; Barker, R.; Haenschel, C.; Baldeweg, T.; Gruzelier, J.H. Hypnosis and event-related potential correlates of error processing in a stroop-type paradigm: A test of the frontal hypothesis. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1997, 27, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, H.J. Brain dynamics and hypnosis: Attentional and disattentional processes. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 1994, 42, 204–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Sanchez, M.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, M.; Santana-Marino, J.; Piqueras-Hernandez, G.; Garcia-Sanchez, A. Learning in deep hypnosis: The potentiation of mental abilities? Rev. Neurol. 1997, 25, 1859–1862. (in Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Hilgard, E.R.; Hilgard, J.R. Hypnosis in the Relief of Pain; Kaufman: Los Altos, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, C.R.; Nakamura, Y. Hypnotic analgesia: A constructivist framework. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 1998, 46, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, J.F.; Dworkin, S.F. Hypnotic control of pain: Historical perspectives and future prospects. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 1997, 45, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pascalis, V. Event-related potentials during hypnotic hallucination. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Hypn. 1994, 42, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pascalis, V.; Perrone, M. EEG asymmetry and heart rate during experience of hypnotic analgesia in high and low hypnotizables. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1996, 21, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, P.M.; Brown, G.; Hoverstad, R.; Widing, R.E. Disclosure of contextually hidden sexual images embedded in an advertisement. Psychol. Rep. 1997, 81, 333–334. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, G. Subliminal perception on TV. Nature 1994, 370, 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, A.; Pappas, Z.; Silverman, M.; Gay, R. What we see: Inattention and the capture of attention by meaning. Conscious. Cogn. 2002, 11, 488–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, P.; Sonnby-Borgström, M. Effects of pictures of emotional faces on tonic and phasic autonomic cardiac control in women and men. Biol. Psychol. 2003, 62, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel, A.J. Conscious and unconscious perception: Experiments on visual masking and word recognition. Cogn. Psychol. 1983, 15, 197–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, K.A.; Narens, L.; Goldfarb, K.; Nelson, T.O. The influence of near-threshold priming on meta-memory and recall. Acta Psychol. 1990, 73, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draine, S.C.; Greenwald, A.G. Replicable unconscious semantic priming. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1998, 127, 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Klinger, M.R.; Schuh, E.S. Activation by marginally perceptible stimuli: Dissociation of unconscious from conscious cognition. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1995, 124, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Klinger, M.R.; Liu, T.J. Unconscious processing of dichoptically masked words. Mem. Cogn. 1989, 17, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehaene, S.; Naccache, L.; le Clec, H.G.; Koechlin, E.; Mueller, M.; Dehaene-Lambertz, G.; van de Moortele, P.F.; le Bihan, D. Imaging unconscious semantic priming. Nature 1998, 395, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevrin, H.; Smith, W.H.; Fritzler, D.E. Average evoked response and verbal correlates of unconscious mental processes. Psychophysiology 1971, 8, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst-Wilson, M.R.; Zajonc, B. Affective discrimination of stimuli that cannot be recognized. Science 1980, 207, 557–558. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein, R.F.; d’Agostino, P.R. Stimulus recognition and the mere exposure effect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, R.; Dolan, R.J. Neural response during preference and memory judgements for subliminally presented stimuli: A functional neuroimaging study. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 4697–4704. [Google Scholar]

- Berns, G.S.; Cohen, J.D.; Mintun, M.A. Brain regions responsive to novelty in the absence of awareness. Science 1997, 276, 1272–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.S.; Bernat, E.; Bunce, S.; Shevrin, H. Brain indices of non-conscious associative learning. Conscious. Cogn. 1997, 6, 519–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, P.; Rübeling, H. Behavioral effect of a subliminal (masked) signal. Z. Exp. Angew. Psychol. 1994, 41, 678–697. [Google Scholar]

- Chakalis, E.; Lowe, G. Positive effects of subliminal stimulation on memory. Percept. Mot. Skills 1992, 74, 956–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Houwer, J.; Hendricks, H.; Baeyens, F. Evaluative learning with subliminally presented stimuli. Conscious. Cogn. 1997, 61, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleyers, G.; Corneille, O.; Luminet, O.; Yzerbyt, V. Aware and (dis)liking: Item-based analyses reveal that valence acquisition via evaluative conditioning emerges only when there is contingency awareness. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2007, 33, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.M.; Swets, J.A. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Battersby, W.S.; Defabaugh, G.L. Neural limitations of visual excitability: After-effects of subliminal stimulation. Vis. Res. 1969, 9, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikowski, J.J.; King-Smith, P.E. Spatial arrangement of line, edge and grating detectors revealed by subthreshold summation. Vis. Res. 1973, 13, 1455–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazdil, M.; Rektor, I.; Dufek, M.; Jurak, P.; Daniel, P. Effect of subthreshold target stimuli on event related potentials. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1998, 107, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp, B. Bright lines and edges facilitate the detection of small light targets. Spat. Vis. 1993, 7, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp, B.; Bonnet, C. Subthreshold summation with illusory contours. Vis. Res. 1995, 35, 1017–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Dresp, B.; Grossberg, S. Contour integration across polarities and spatial gaps: From local contrast filtering to global grouping. Vis. Res. 1997, 37, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp, B.; Grossberg, S. Detection facilitation by color and luminance edges: Boundary, surface, and attentional factors. Vis. Res. 1999, 39, 3431–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp, B. Dynamic characteristics of spatial mechanisms coding contour structures. Spat. Vis. 1999, 12, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, M.K.; Ito, M.; Gilbert, C.D.; Westheimer, G. Improvement in visual sensitivity by changes in local context: Parallel studies in human observers and in V1 of alert monkeys. Neuron 1995, 15, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskrantz, L. Blindsight: A Case Study and Implications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Weiskrantz, L. Blindsight revisited. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1996, 6, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel, A.J. Blindsight and shape perception: Deficit of visual consciousness or of visual function? Brain 1998, 121, 1565–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowey, A.; Stoerig, P. Blindsight in monkeys. Nature 1995, 373, 247–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, F.C.; Braun, J. Blindsight in normal observers. Nature 1995, 377, 336–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.M.; Alvarez, G.A. Give me liberty or give me more time! Visual attention is faster if you don’t tell it what to do. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1999, 40, S796. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki, P.; Hill, T.; Czyzewska, M. Non-conscious acquisition of information. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, G.; Grossberg, S. Pattern Recognition by Self-Organizing Neural Networks; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J.G. Breakthrough to awareness: A preliminary neural network model of conscious and unconscious perception in word processing. Biol. Cybern. 1996, 75, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margulis, M.; Tang, C.M. Temporal integration can readily switch between sublinear and supralinear summation. J. Neurophysiol. 1998, 79, 2809–2813. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, J.P. Another opening in the explanatory gap. Conscious. Cogn. 1998, 7, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tononi, G.; Sporns, O.; Edelman, G.M. Reentry and the problem of integrating multiple cortical areas: Simulation of dynamic integration in the visual system. Cereb. Cortex 1992, 2, 310–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V.S. Consciousness and body image: Lessons from phantom limbs, Capgras syndrome and pain asymbolia. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1998, 353, 1851–1859. [Google Scholar]

- Di Lollo, V.; Enns, J.T.; Rensink, R.A. Competition for consciousness among visual events: The psychophysics of reentrant visual processes. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2000, 129, 481–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, G.; Wojciulik, E.; Clarke, K.; Husain, M.; Frith, C.; Driver, J. Neural correlates of conscious and unconscious vision in parietal extinction. Neurocase 2002, 8, 387–393. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, G. Neural correlates of the contents of visual awareness in humans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 362, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresp, B. Effect of practice on the visual detection of near-threshold lines. Spat. Vis. 1998, 11, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourneret, P.; Jeannerod, M. Limited conscious monitoring of motor performance in normal subjects. Neuropsychologia 1998, 36, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongers, K.C.A.; Dijksterhuis, A. Consciousness as a Trouble Shooting Device? The Role of Consciousness in Goal-Pursuit. In The Oxford Handbook of Human Action; Morsella, E., Bargh, J.A., Gollwitzer, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 589–604. [Google Scholar]

- Churchland, P.S. Brain-Wise: Studies in Neurophilosophy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, A.; Konig, P.; Kreiter, A.; Schillen, T.; Singer, W. Temporal coding in the visual cortex: New vistas on integration in the nervous system. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1992, 15, 218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Stockmanns, G.; Kochs, E.; Nahm, W.; Thornton, C.; Kalkmann, C.J. Automatic Analysis of Auditory Evoked Potentials by Means of Wavelet Analysis. In Memory and Awareness in Anaesthesia IV; Jordan, D.C., Vaughan, D.J.A., Newton, D.E.F., Eds.; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2000; pp. 117–131. [Google Scholar]

- Llinás, R.; Ribary, U. Coherent 40-Hz oscillation characterizes dream states in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 2078–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBerge, S. Lucid dreaming: Psychophysiological Studies of Consciousness During REM Sleep. In Sleep and Cognition; Bootzen, R.R., Kihlstrom, J.F., Schacter, D.L., Eds.; APA Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- Abeles, M.; Bergman, H.; Margalit, E.; Vaadia, E. Spatiotemporal firing patterns in the frontal cortex of behaving monkeys. J. Neurophysiol. 1993, 70, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, P.-M.; Bi, G.-Q. Synaptic mechanisms of persistent reverberating activity in neuronal networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 10333–10338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llinás, R.; Ribary, U. Consciousness and the brain: The thalamo-cortical dialogue in health and disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 929, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steriade, M. Synchronized activities of coupled oscillators in the cerebral cortex and thalamus at different levels of vigilance. Cereb. Cortex 1997, 7, 583–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamme, V.A.F. Towards a true neuronal stance in consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006, 10, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamme, V.A.F. Separate neural definitions of visual consciousness and visual attention: A case for phenomenal awareness. Neural Netw. 2004, 17, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V.S.; Rogers-Ramachandran, D.; Cobb, S. Touching the phantom limb. Nature 1995, 377, 489–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guéniot, T. D’une hallucination du toucher (hétérotopie subjective des extrémités) particulière à certains amputés. J. Physiol. L’Homme Anim. 1868, 4, 416–418. [Google Scholar]

- Merzenich, M.M.; Nelson, R.J.; Stryker, M.S.; Cynader, M.S.; Schoppmann, A.; Zook, J.M. Somatosensory cortical map changes following digit amputation in adult monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol. 1984, 224, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V.S.; Rogers-Ramachandran, D.; Stewart, M. Perceptual correlates of massive cortical reorganization. Science 1992, 258, 1159–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Hebb, D.O. Distinctive Features of Learning in the Higher Animal. In Brain Mechanisms and Learning; Delafresnaye, J.F., Ed.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1961. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Dresp-Langley, B. Why the Brain Knows More than We Do: Non-Conscious Representations and Their Role in the Construction of Conscious Experience. Brain Sci. 2012, 2, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2010001

Dresp-Langley B. Why the Brain Knows More than We Do: Non-Conscious Representations and Their Role in the Construction of Conscious Experience. Brain Sciences. 2012; 2(1):1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleDresp-Langley, Birgitta. 2012. "Why the Brain Knows More than We Do: Non-Conscious Representations and Their Role in the Construction of Conscious Experience" Brain Sciences 2, no. 1: 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2010001

APA StyleDresp-Langley, B. (2012). Why the Brain Knows More than We Do: Non-Conscious Representations and Their Role in the Construction of Conscious Experience. Brain Sciences, 2(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci2010001