Current State of the Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Stroke: A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

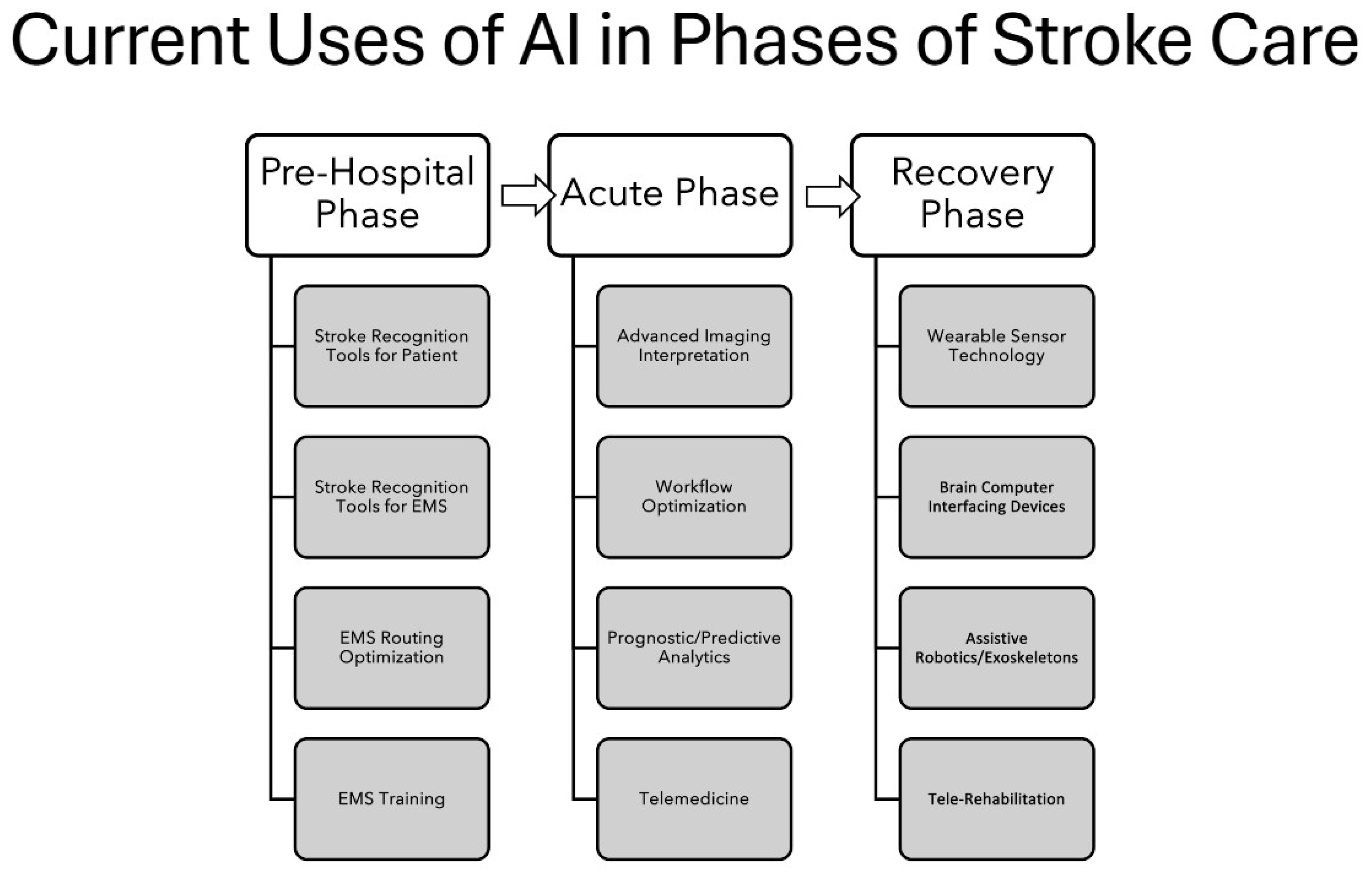

3.1. Summary of Types of Existing Literature on AI Used for Stroke Care Across All Phases

3.2. Summary of AI Use in Pre-Hospital Phase of Care

3.3. Summary of AI Use in the Acute Phase of Care

3.4. Summary of AI Use in the Recovery Phase of Care

4. Discussion

5. Limitations of This Review

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| RCTs | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| LVO | Large Vessel Occlusion |

| EMS | Emergency Medical Services |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| TCD | Transcranial Doppler |

References

- Saver, J.L. Time is Brain-quantified. Stroke 2006, 37, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.M.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2023 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, E93–E621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhemer, O.A.; Fransen, P.S.S.; Beumer, D.; van den Berg, L.A.; Lingsma, H.F.; Yoo, A.J.; Schonewille, W.J.; Vos, J.A.; Nederkoorn, P.J.; Wermer, M.J.H.; et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Demchuk, A.M.; Menon, B.K.; Eesa, M.; Rempel, J.L.; Thornton, J.; Roy, D.; Jovin, T.G.; Willinsky, R.A.; Sapkota, B.L.; et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saver, J.L.; Goyal, M.; Bonafe, A.; Diener, H.C.; Levy, E.I.; Pereira, V.M.; Albers, G.W.; Cognard, C.; Cohen, D.J.; Hacke, W.; et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.C.V.; Mitchell, P.J.; Kleinig, T.J.; Dewey, H.M.; Churilov, L.; Yassi, N.; Yan, B.; Dowling, R.J.; Parsons, M.W.; Oxley, T.J.; et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovin, T.G.; Chamorro, A.; Cobo, E.; de Miquel, M.A.; Molina, C.A.; Rovira, A.; San Román, L.; Serena, J.; Abilleira, S.; Ribó, M.; et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2296–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Menon, B.K.; van Zwam, W.H.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Mitchell, P.J.; Demchuk, A.M.; Dávalos, A.; Majoie, C.B.L.M.; van der Lugt, A.; de Miquel, M.A.; et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016, 387, 1723–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeme, S.; Kottenmeier, E.; Uzochukwu, G.; Albright, K.C.; Brinjiki, W. Evidence-Based Disparities in Stroke Care Metrics and Outcomes in the United States: A Systematic Review. Stroke 2022, 53, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja-Ruiz, C.; Akinyemi, R.; Lucumi-Cuesta, D.I.; Owolabi, M.O.; Pandian, J.D.; Strong, K.; Feigin, V.L.; Bennett, D.A.; O’Donnell, M.J.; Mensah, G.A.; et al. Socioeconomic status and stroke: A review of the latest evidence on inequalities and their drivers. Stroke 2025, 56, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koska, I.O.; Selver, A. Artificial intelligence in stroke imaging: A comprehensive review. Eurasian J. Med. 2023, 55, S91–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolcott, Z.C.; English, S.W. Artificial intelligence to enhance prehospital stroke diagnosis and triage: A perspective. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1389056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamian, A.; Seifi, A. Diagnostic accuracy of deep learning for intracranial hemorrhage detection in noncontrast brain CT scans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 12, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrabhatla, A.S.; Kuo, E.A.; Sokolowski, J.D.; Kellogg, R.T.; Park, M.; Mastorakos, P. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in the diagnosis and management of stroke: A narrative review of United States Food and Drug Administration-approved technologies. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, W.; Li, Z.; Rong, Z.; Wang, X.; Han, J.; Ma, L. A 25-year retrospective of artificial intelligence for diagnosing acute stroke. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e59711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo Sierra, N.; Hernández Rincón, E.H.; Osorio Betancourt, G.A.; Ramos Chaparro, P.A.; Diaz Quijano, D.M.; Barbosa, S.D.; Hernandez Restrepo, M.; Uriza Sinisterra, G. Use of artificial intelligence in the management of stroke: Scoping review. Front. Radiol. 2025, 5, 1593397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeralal, V.T.; Chadee, S.E.; Ilyaev, B.; Ilyaev, R.; Ilyayeva, S. Artificial intelligence in stroke care: A narrative review of diagnostic, predictive, and workflow applications. Cureus 2025, 17, e93430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J. Application of artificial intelligence in acute ischemic stroke: A scoping review. Neurointervention 2025, 20, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Song, S.; He, T. Application and challenges of artificial intelligence in the care of stroke patients. J. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2025, 9, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.F.; Chen, Z.J.; Lin, Y.Y.; Lin, Z.Q.; Chen, C.N.; Yang, M.L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Li, Y.Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.H.; et al. Stroke risk study based on deep learning-based magnetic resonance imaging carotid plaque automatic segmentation algorithm. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, M.; Song, H.; Wu, X.; Li, G.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhao, S.; Chen, J.; et al. Predicting ischemic stroke risk from atrial fibrillation based on multi-spectral fundus images using deep learning. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1185890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messica, S.; Presil, D.; Hoch, Y.; Lev, T.; Hadad, A.; Katz, O.; Cohen, O.; Lunt, S.; Gilead, I.; Tsfadia, Y.; et al. Enhancing stroke risk and prognostic timeframe assessment with deep learning and a broad range of retinal biomarkers. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 154, 102927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Shang, K.; Wei, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; et al. Deep learning-based automatic ASPECTS calculation can improve diagnosis efficiency in patients with acute ischemic stroke: A multicenter study. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostmeier, S.; Axelrod, B.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, B.; Yuen, N.; Rao, V.M.; Mittal, S.; Shuaib, A.; Figueiredo, G.; et al. Random expert sampling for deep learning segmentation of acute ischemic stroke on non-contrast CT. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2025, 17, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohapatra, S.; Lee, T.H.; Sahoo, P.K.; Wu, C.Y. Localization of early infarction on non-contrast CT images in acute ischemic stroke with deep learning approach. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, C.M.; Abdullah, A.R.; Smith, S.C.; Jones, D.S.; Patel, M.R.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Giri, J.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; et al. 2025 ACC/AHA guideline core principles and development process: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Os, H.J.A.; Ramos, L.A.; Hilbert, A.; van Leeuwen, M.; van Walderveen, M.A.A.; Kruyt, N.D.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Steyerberg, E.W.; van der Schaaf, I.C.; Lingsma, H.F.; et al. Predicting outcome of endovascular treatment for acute ischemic stroke: Potential value of machine learning algorithms. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, J.; Yoon, J.G.; Park, H.; Kim, Y.D.; Nam, H.S.; Heo, J.H. Machine learning-based model for prediction of outcomes in acute stroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 1263–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-S.; Lee, E.-J.; Chang, D.-I.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, J.; Cha, J.-K.; Park, M.-S.; Yu, K.H.; Jung, J.-M.; Ahn, S.H.; et al. A multimodal ensemble deep learning model for functional outcome prognosis of stroke patients. J. Stroke 2024, 26, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, L.; Kook, L.; Hamann, J.; Globas, C.; Heldner, M.R.; Seiffge, D.; Antonenko, K.; Dobrocky, T.; Panos, L.; Kaesmacher, J.; et al. Deep learning versus neurologists: Functional outcome prediction in LVO stroke patients undergoing mechanical thrombectomy. Stroke 2023, 54, 1761–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Shah, P.; Yu, Y.; Horsey, J.; Ouyang, J.; Jiang, B.; Yang, G.; Heit, J.J.; McCullough-Hicks, M.E.; Hugdal, S.M.; et al. A clinical and imaging fused deep learning model matches expert clinician prediction of 90-day stroke outcomes. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2024, 45, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Polson, J.S.; Wang, Z.; Nael, K.; Rao, N.M.; Speier, W.F.; Yeung, V.; Kazim, S.F.; Liu, X.; Ali, A.; et al. A deep learning approach to predict recanalization first-pass effect following mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2024, 45, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velagapudi, L.; Mouchtouris, N.; Schmidt, R.F.; Vuong, D.; Khanna, O.; Sweid, A.; Hasan, T.F.; Ospel, J.M.; Mehta, B.P.; Tjoumakaris, S.I.; et al. A machine learning approach to first pass reperfusion in mechanical thrombectomy: Prediction and feature analysis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 30, 105796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Luo, S.; Cui, X.; Qu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, Q. Machine learning-based predictive model for the development of thrombolysis resistance in patients with acute ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol. 2024, 24, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangelo, G.; Ribó, M.; Montiel, E.; Dominguez, D.; Olivé-Gadea, M.; Muchada, M.; Quintana, M.; Poca, M.A.; Dávalos, A.; Boada, I.; et al. PRERISK: A personalized, artificial intelligence-based and statistically-based stroke recurrence predictor for recurrent stroke. Stroke 2024, 55, 1200–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Z.A.; Zhai, X.Y.; Han, L.; Zhang, P.; Cheng, S.J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Song, J.; Li, H.; et al. An interpretable machine learning model for stroke recurrence in patients with symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic arterial stenosis. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1323270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Genaidy, A.; Tran, G.; Marroquin, P.; Estes, C.; Sloop, S. Improving stroke risk prediction in the general population: A comparative assessment of common clinical rules, a new multimorbid index, and machine-learning-based algorithms. Thromb. Haemost. 2022, 122, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodencarevic, A.; Weingärtner, M.; Caro, J.J.; Ukalovic, D.; Zimmermann-Rittereiser, M.; Schwab, S.; Paul, F.; Heller, E.; Koch, P.; Heuschmann, P.U.; et al. Prediction of recurrent ischemic stroke using registry data and machine learning methods: The Erlangen Stroke Registry. Stroke 2022, 53, 2299–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Askari, M.; Altman, R.B.; Schmitt, S.K.; Fan, J.; Bentley, J.P.; Zhang, S.; Neubeck, L.; Wang, X.; Zou, J.; et al. Atrial fibrillation burden signature and near-term prediction of stroke: A machine learning analysis. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 12, e005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ruan, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sang, Y.; Guo, J.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, K.; et al. Machine learning improves risk stratification of coronary heart disease and stroke. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.J.; Agasthi, P.; Barry, T.; Chiang, C.C.; Wang, P.; Ashraf, H.; Siddiqui, T.; Mamas, M.A.; McCrae, K.; Vemulapalli, S.; et al. Using artificial intelligence in predicting ischemic stroke events after percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2023, 35, e297–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Ding, L.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, L. Machine learning-based models for prediction of the risk of stroke in coronary artery disease patients receiving coronary revascularization. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, T.; Jain, P.K.; Suri, H.S.; Londhe, N.D.; Ikeda, N.; El-Baz, A.; Shrivastava, V.K.; Saba, L.; Nicolaides, A.; Shafique, S.; et al. Stroke risk stratification and its validation using ultrasonic echolucent carotid wall plaque morphology: A machine learning paradigm. Comput. Biol. Med. 2017, 80, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, P.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, T.; Wei, X.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, X.; Feng, W.; et al. Risk factors of cerebral infarction and myocardial infarction after carotid endarterectomy analyzed by machine learning. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2020, 2020, 6217392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.S.; Li, L.Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.Z. Stroke risk prediction by color Doppler ultrasound of carotid artery-based deep learning using Inception V3 and VGG-16. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1111906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, A.R.; Welikala, R.; Barman, S.; Foster, P.J.; Luben, R.; Hayat, S.; Khaw, K.T.; Whincup, P.; Strachan, D.; Owen, C.G.; et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled retinal vasculometry for prediction of circulatory mortality, myocardial infarction and stroke. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 1722–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guberina, N.; Dietrich, U.; Radbruch, A.; Goebel, J.; Deuschl, C.; Ringelstein, A.; Kornhuber, M.; Buerger, K.; Heiland, S.; Sure, U.; et al. Detection of early infarction signs with machine learning-based diagnosis by means of the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT score (ASPECTS) in the clinical routine. Neuroradiology 2018, 60, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelter, P.; Muehlen, I.; Goelitz, P.; Beuscher, V.; Schwab, S.; Doerfler, A. Automated ASPECT scoring in acute ischemic stroke: Comparison of three software tools. Neuroradiology 2020, 62, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delio, P.R.; Wong, M.L.; Tsai, J.P.; Hinson, H.E.; McMenamy, J.; Le, T.Q.; Ospel, J.M.; Mehta, B.P.; Lindsay, P.; Hill, M.D.; et al. Assistance from automated ASPECTS software improves reader performance. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 30, 105829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsoukas, S.; Morey, J.; Lock, G.; Chada, D.; Shigematsu, T.; Marayati, N.F.; Munoz, C.; Hess, C.; Bonafé, A.; Jovin, T.G.; et al. AI software detection of large vessel occlusion stroke on CT angiography: A real-world prospective diagnostic test accuracy study. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2023, 15, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkharghani, S.; Lansberg, M.G.; Venkatsubramanian, C.; Cereda, C.; Lima, F.O.; Coelho, H.; Mlynash, M.; Kim, A.S.; Olivot, J.M.; Bammer, R.; et al. High-performance automated anterior circulation CT angiographic clot detection in acute stroke: A multireader comparison. Radiology 2021, 298, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunwald, I.Q.; Kulikovski, J.; Reith, W.; Gerry, S.; Namias, R.; Politi, M.; Lynch, J.R.; Sommer, W.H.; Meyer, L.; Stolz, E.; et al. Collateral automation for triage in stroke: Evaluating automated scoring of collaterals in acute stroke on computed tomography scans. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 47, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czap, A.L.; Bahr-Hosseini, M.; Singh, N.; Yamal, J.M.; Nour, M.; Parker, S.; Gupta, R.; Nesbit, G.M.; Peterson, E.C.; Fruth, O.; et al. Machine learning automated detection of large vessel occlusion from mobile stroke unit computed tomography angiography. Stroke 2022, 53, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Kuang, H.; Teleg, E.; Ospel, J.M.; Sohn, S.I.; Almekhlafi, M.A.; Coutts, S.B.; Hill, M.D.; Demchuk, A.M.; Goyal, M.; et al. Machine learning for detecting early infarction in acute stroke with non-contrast-enhanced CT. Radiology 2020, 294, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, H.; Ishii, A.; Tsuji, H.; Fuchigami, T.; Sasaki, N.; Tachibana, A.; Yokote, K.; Ohara, S.; Sakai, K.; Uemura, J.; et al. Automatic ischemic core estimation based on noncontrast-enhanced computed tomography. Stroke 2023, 54, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, S.; Grauhan, N.F.; Brockstedt, L.; Kondova, M.; Schmidtmann, I.; Paul, R.; Dinkel, J.; Fritz, J.; Lobsien, D.; Shah, J.; et al. Ultrafast brain MRI with deep learning reconstruction for suspected acute ischemic stroke. Radiology 2024, 310, e231938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, S.H.; Cho, Y.; Kim, B.; Yang, K.S.; Kim, I.; Kim, B.K.; Im, S.H.; Park, H.M.; Lee, S.J.; Seo, D.W.; et al. Deep learning-based synthetic TOF-MRA generation using time-resolved MRA in fast stroke imaging. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2023, 44, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenstrup, J.; Havtorn, J.D.; Borgholt, L.; Blomberg, S.N.; Maaloe, L.; Sayre, M.R.; Deal, M.; Lee, H.K.; Persson, O.; Lauritsen, S.M.; et al. A retrospective study on machine learning-assisted stroke recognition for medical helpline calls. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Chang, H.J.; Nam, H.S. Use of machine learning classifiers and sensor data to detect neurological deficit in stroke patients. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Liang, H.; Hu, B.; Ren, L.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, T.; Yang, L.; et al. Early identification of stroke through deep learning with multi-modal human speech and movement data. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel, H.; Navi, B.B.; Parikh, N.S.; Merkler, A.E.; Okin, P.M.; Devereux, R.B.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Iadecola, C.; Healey, J.S.; Wintermark, M.; et al. Machine learning prediction of stroke mechanism in embolic strokes of undetermined source. Stroke 2020, 51, e203–e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinstein, A.A.; Yost, M.D.; Faust, L.; Kashou, A.H.; Latif, O.S.; Graff-Radford, J.; Siegler, J.E.; Weingart, J.D.; Lopes, D.K.; Mesfin, F.B.; et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled ECG to identify silent atrial fibrillation in embolic stroke of unknown source. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 30, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, W.S.; Schellingerhout, D.; Lee, H.; Lee, K.J.; Kim, C.K.; Kim, B.J.; Kwon, S.U.; Hong, K.S.; Heo, T.W.; Kim, H.C.; et al. Deep learning-based automatic classification of ischemic stroke subtype using diffusion-weighted images. J. Stroke 2024, 26, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Lee, H.; Seog, Y.; Kim, S.; Baek, J.H.; Park, H.; Lee, D.H.; Yoon, B.H.; Sohn, S.I.; Nam, H.S.; et al. Cancer prediction with machine learning of thrombi from thrombectomy in stroke: Multicenter development and validation. Stroke 2023, 54, 2105–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, S.D.; Liu, J.; Bullrich, M.B.; Sharma, M.; Boulton, M.; Pandey, S.K.; Cheloth, N.D.; Saini, V.; Khatri, P.; Demchuk, A.M.; et al. Deep learning prediction of stroke thrombus red blood cell content from multiparametric MRI. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2024, 30, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, M.; Sun, C.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, F.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; et al. Using machine learning to predict stroke-associated pneumonia in Chinese acute ischemic stroke patients. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 1656–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Su, S.Y.; Sung, S.F. Machine learning-based survival analysis approaches for predicting the risk of pneumonia post-stroke discharge. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2024, 186, 105422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, X.; Lai, L.; Qu, C. Application of interpretable machine learning algorithms to predict acute kidney injury in patients with cerebral infarction in ICU. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2024, 33, 107729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Yoo, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, I.H.; Kim, J.S.; Park, E.; Nam, H.S.; Kim, Y.D.; Hong, K.S.; Sohn, S.I.; et al. Prediction of hidden coronary artery disease using machine learning in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 2022, 99, e55–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Benlamri, R.; Diner, T.; Cristofaro, K.; Dillistone, L.; Khallouki, H.; Gauthier, S.; Dubeau, C.; Singh, B.; Hachinski, V.; et al. An app for navigating patient transportation and acute stroke care in Northwestern Ontario using machine learning: Retrospective study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e54009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.Z.; Yeo, M.; Dahan, A.; Tahayori, B.; Kok, H.K.; Abbasi-Rad, M.; Ng, J.; Lim, Z.Y.; Wong, Z.R.; Tan, J.Y.; et al. Development of a machine learning-based real-time location system to streamline acute endovascular intervention in acute stroke: A proof-of-concept study. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2022, 14, 799–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiramal, J.A.; Johnson, J.; Webster, J.; Nag, D.R.; Robert, D.; Ghosh, T.; Golla, S.; Pawar, S.; Krishnan, P.; Drain, P.K.; et al. Artificial intelligence-based automated CT brain interpretation can improve uptake of lifesaving interventions in resource-limited settings. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0003351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agripnidis, T.; Ayobi, A.; Quenet, S.; Beland, B.; Smith, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Roberts, J.; Patel, M.; Johnson, K.; et al. Performance of an artificial intelligence tool for multi-step acute stroke imaging: A multicenter diagnostic study. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2025, 15, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardsen, A.C.L.; Hardeland, C.; Dehre, A.; Vik, E.; Jensen, T.; Hansen, R.; Pedersen, L.; Olsson, C.; Nilsson, A.; Larsson, K.; et al. Emergency medical services providers’ perspectives on the use of artificial intelligence in prehospital identification of stroke: A qualitative study in Norway and Sweden. BMC Emerg. Med. 2025, 25, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, K.; Wisniewski, D.; Ari, A.; Johnson, T.; Smith, P.; Li, J.; Patel, R.; Nguyen, M.; Chen, L.; Brown, A.; et al. Investigation into application of AI and telemedicine in rural communities: A systematic literature review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouridsen, K.; Thurner, P.; Zaharchuk, G. Artificial intelligence applications in stroke. Stroke 2020, 51, 2573–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, F.; Yang, J.; Xu, T.; Huang, Q.; et al. Artificial intelligence in ischemic stroke images: Current applications and future directions. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1418060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, C.H.; Tanwar, M.; Abou Elkassem, A.; Patel, P.; Li, Y.; Wong, T.; Chen, R.; Smith, J.; Brown, M.; Garcia, L.; et al. Prospective evaluation of artificial intelligence triage of intracranial hemorrhage on noncontrast head CT examinations. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2024, 223, e243–e1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceklic, E.; Ball, S.; Finn, J.; Brown, E.; Brink, D.; Bailey, P.; Smith, K.; Cameron, P.; Fitzgerald, M.; Walker, T.; et al. Ambulance dispatch prioritisation for traffic crashes using machine learning: A natural language approach. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2022, 168, 104886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rava, R.A.; Peterson, E.D.; Hastrup, S.; Mocco, J.; Smith, W.S.; Saver, J.L.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Jahan, R.; Jovin, T.G.; Nogueira, R.G.; et al. AI routing on mobile stroke units. Stroke 2021, 52, 3541–3550. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, A.; Guerrero, W.R.; Pérez De La Ossa, N. Prehospital stroke triage. Neurology 2021, 97, S25–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasselius, J.; Finn, E.L.; Persson, E.; Song, G.; Wu, S.; Feng, S.; Lindgren, A.; Norrving, B.; Engström, G.; Svensson, P.; et al. Detection of unilateral arm paresis after stroke by wearable accelerometers and machine learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, M.L.; Collatz-Christensen, H.; Blomberg, S.N.F.; Boebel, S.; Verhoeven, J.; Krafft, T. Artificial intelligence in emergency medical services dispatching: Assessing the potential impact of an automatic speech recognition software on stroke detection taking the Capital Region of Denmark as case in point. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2022, 30, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stigt, M.N.; Groenendijk, E.A.; Van Meenen, L.C.C.; van de Munckhof, A.; Coutinho, J.M.; de Maat, M.P.M.; Kerkhof, F.; van der Worp, H.B.; Roos, Y.B.W.E.M.; Dippel, D.W.J.; et al. Prehospital detection of large vessel occlusion stroke with EEG: Results of the ELECTRA-STROKE study. Neurology 2023, 101, e2522–e2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caceres, J.A.; Adil, M.M.; Jadhav, V.; Chaudhry, S.A.; Pawar, S.; Rodriguez, G.J.; Suri, M.F.K.; Qureshi, A.I. Diagnosis of stroke by emergency medical dispatchers and its impact on the prehospital care of patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013, 22, e610–e614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oostema, J.A.; Chassee, T.; Reeves, M. Emergency dispatcher stroke recognition: Associations with downstream care. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2018, 22, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Band, R.; Abboud, M.E.; Pajerowski, W.; Guo, M.; David, G.; Katz, J.M.; Newgard, C.D.; Callaway, C.W.; Pines, J.M.; et al. Accuracy of emergency medical services dispatcher and crew diagnosis of stroke in clinical practice. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottle, J. Virtual reality and the transformation of medical education. Future Healthc. J. 2019, 6, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bat-Erdene, B.O.; Saver, J.L. Automatic acute stroke symptom detection and emergency medical systems alerting by Mobile health technologies: A review. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 30, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, K.S. A smartphone-based automatic diagnosis system for facial nerve palsy. Sensors 2015, 15, 26756–26768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raychev, R.I.; Saver, J.L.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Penkov, S.; Angelov, D.; Stoev, K.; Kim, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Patel, R.; et al. Abstract WMP120: Development of smartphone-enabled machine learning algorithms for autonomous stroke detection. Stroke 2023, 54, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figurell, M.E.; Meyer, D.M.; Perrinez, E.S.; Mills, M.T.; Shuey, H.M.; Wu, D.; Vyas, R.; Carroll, J.; Amin-Hanjani, S.; Almekhlafi, M.A.; et al. Viz.ai implementation of stroke augmented intelligence and communications platform to improve indicators and outcomes for a comprehensive stroke center and network. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2023, 44, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunda, B.; Neuhaus, A.; Sipos, I.; Toth, G.; Jovin, T.G.; Nogueira, R.G.; Mocco, J.; Fargen, K.M.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Yan, B.; et al. Improved stroke care in a primary stroke center using AI-decision support. Cerebrovasc. Dis. Extra 2022, 12, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, N.C.; Entezami, P.; Boulos, A.S.; Eker, O.; Heit, J.J.; Shakir, H.; Cruz-Gonzalez, I.; Jovin, T.G.; Nogueira, R.G.; Fargen, K.M.; et al. Artificial intelligence improves transfer times and ischemic stroke workflow metrics. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2023, 29, 15910199231209080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, T.; Collins, G.; Heath, G.W.; Majid, A.; Huang, Y.; Nogueira, R.G.; Jovin, T.G.; Fargen, K.M.; Menon, B.K.; Almekhlafi, M.A.; et al. VALIDATE—Utilization of the Viz.ai mobile stroke care coordination platform to limit delays in LVO stroke diagnosis and endovascular treatment. Front. Stroke 2024, 3, 1381930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.E.; Ringheanu, V.M.; Preston, L.; Alqaisi, F.; Fargen, K.M.; Nogueira, R.G.; Jovin, T.G.; Mocco, J.; Menon, B.K.; Zaidat, O.O.; et al. Artificial intelligence–parallel stroke workflow tool improves reperfusion rates and door-in to puncture interval. Stroke Vasc. Interv. Neurol. 2022, 2, e000224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olive-Gadea, M.; Crespo, C.; Granes, C.; Hernandez-Perez, M.; Laredo, C.; Renard, D.; Gory, B.; Lapergue, B.; Blanc, R.; Piotin, M.; et al. Deep Learning Based Software to Identify Large Vessel Occlusion on Noncontrast Computed Tomography. Stroke 2020, 51, 3133–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLouth, J.; Elstrott, S.; Chaibi, Y.; Toth, G.; Fraser, J.F.; Jovin, T.G.; Nogueira, R.G.; Jadhav, A.P.; Mocco, J.; Menon, B.K.; et al. Validation of a deep learning tool in the detection of intracranial hemorrhage and large vessel occlusion. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 656112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahav-Dovrat, A.; Saban, M.; Merhav, G.; Lankri, I.; Abergel, E.; Eran, A.; Tanne, D.; Nogueira, R.G.; Sivan-Hoffmann, R. Evaluation of artificial intelligence-powered identification of large-vessel occlusions in a comprehensive stroke center. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlossman, J.; Ro, D.; Salehi, S.; Chow, D.; Yu, W.; Chang, P.D.; Soun, J.E. Head-to-head comparison of commercial artificial intelligence solutions for detection of large vessel occlusion at a comprehensive stroke center. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijten, S.P.R.; Wolff, L.; Duvekot, M.H.C.; van Doormaal, P.J.; Moudrous, W.; Kerkhoff, H.; Lycklama, A.N.; Bokkers, R.P.H.; Yo, L.S.F.; Hofmeijer, J.; et al. Diagnostic performance of an algorithm for automated large vessel occlusion detection on CT angiography. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2022, 14, 794–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimflova, P.; Golan, R.; Ospel, J.M.; Sojoudi, A.; Duszynski, C.; Elebute, I.; El-Hariri, H.; Hossein Mousavi, S.; Neto, L.A.S.M.; Pinky, N.; et al. Validation of a machine learning software tool for automated large vessel occlusion detection in patients with suspected acute stroke. Neuroradiology 2022, 64, 2245–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathla, G.; Durjoy, D.; Priya, S.; Samaniego, E.; Derdeyn, C.P. Image-level detection of large vessel occlusion on 4D-CTA perfusion data using deep learning in acute stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2022, 31, 106757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamou, A.; Beltsios, E.T.; Bania, A.; Katsanos, A.H.; Mavridis, D.; Mavridis, K.; Tsioufis, C.; Tsivgoulis, G.; Papadopoulos, D.; Tzoumas, N.; et al. Artificial intelligence-driven aspects for the detection of early stroke changes in non-contrast CT: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2023, 15, e298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, L.; Berkhemer, O.A.; Fransen, P.S.; van Zwam, W.H.; Lingsma, H.F.; van den Berg, L.A.; Beumer, D.; van Oostenbrugge, R.J.; Majoie, C.B.; Roos, Y.B.; et al. Validation of automated Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) software for detection of early ischemic changes on non-contrast brain CT scans. Neuroradiology 2021, 63, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Park, G.; Kim, D.; Jung, S.; Song, S.; Hon, J.M.; Shin, D.H.; Lee, J.S. Clinical evaluation of a deep-learning model for automatic scoring of the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score on non-contrast CT. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2024, 16, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Pham, N.; van Staalduinen, E.K.; Tien, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Liu, F.; et al. Deep learning applications in imaging of acute ischemic stroke: A systematic review and narrative summary. Radiology 2025, 315, e240775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwood, B.T.; Meyer, D.; Inonita, C.; Bhogal, P.; McDonough, R.; Goyal, M.; Menon, B.K.; Demchuk, A.M.; Liebeskind, D.S.; Jahan, R.; et al. Multicenter comparison using two AI stroke CT perfusion software packages for determining thrombectomy eligibility. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2024, 33, 107750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Hamid, U.; Zaidat, O.; Qureshi, A.I.; Jadhav, A.P.; Fargen, K.M.; Nogueira, R.G.; Mocco, J.; Jovin, T.G.; Menon, B.K.; et al. Role of artificial intelligence in telestroke: An overview. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 559322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.; Elsherif, S.; Legere, B.; Seetharam, K.; Shuaib, A.; Shuaib, W.; Dineen, R.A.; Jayaraman, M.V.; Jahan, R.; Almekhlafi, M.A.; et al. Is telestroke more effective than conventional treatment for acute ischemic stroke? A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient outcomes and thrombolysis rates. Int. J. Stroke 2023, 19, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez-Guerrero, M.A.; Callejas-Cuervo, M.; Mazzoleni, S. Artificial intelligence-based wearable robotic exoskeletons for upper limb rehabilitation: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Várkuti, B.; Guan, C.; Pan, Y.; Pham, M.; Leeb, R.; Toni, I.; Millán, J.d.R.; Birbaumer, N.; Bütefisch, C.M. Resting state changes in functional connectivity correlate with movement recovery for BCI and robot-assisted upper-extremity training after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2012, 27, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera, M.A.; Soekadar, S.R.; Ushiba, J.; Millán, J.d.R.; Liu, M.; Birbaumer, N.; Cohen, L.G.; Ramos-Murguialday, A. Brain-computer interfaces for post-stroke motor rehabilitation: A meta-analysis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2018, 5, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, D.T.; Souders, L.; Baranyai, K.; Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Frolov, A.; Guan, C.; Várkuti, B.; Kraus, D.; Burianová, J.; Cervera, M.A.; et al. Contralesional brain–computer interface control of a powered exoskeleton for motor recovery in chronic stroke survivors. Stroke 2017, 48, 1908–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Jiang, N.; Stevenson, A.J.; Farina, D.; Dremstrup, K.; Burianová, J.; Kraus, D.; Várkuti, B.; Cervera, M.A.; Guan, C.; et al. Efficient neuroplasticity induction in chronic stroke patients by an associative brain-computer interface. J. Neurophysiol. 2016, 115, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senadheera, I.; Hettiarachchi, P.; Haslam, B.; Jayawardena, S.; Bandara, T.; Perera, H.; de Silva, D.; Fernando, S.; Pathirana, P.; Gunawardena, S.; et al. AI applications in adult stroke recovery and rehabilitation: A scoping review using AI. Sensors 2024, 24, 6585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bütefisch, C.M. Role of the contralesional hemisphere in post-stroke recovery of upper extremity motor function. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobkin, A. A Scoping Review of AI Applications in Adult Stroke Recovery and Rehabilitation. Int. J. Neurorehabilit. 2024, 11, 591. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, Y.J.; Chang, M.C. Use of machine learning in stroke rehabilitation: A narrative review. Brain Neurorehabilit. 2022, 15, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sale, P.; Ferriero, G.; Ciabattoni, L.; Cortese, A.M.; Ferracuti, F.; Romeo, L.; Piccione, F.; Masiero, S. Predicting Motor and Cognitive Improvement Through Machine Learning Algorithm in Human Subject that Underwent a Rehabilitation Treatment in the Early Stage of Stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018, 27, 2962–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, S.W.; Jeong, T.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, Y.; Lim, J.; Han, K.; Jung, H.; Oh, M.; Kang, H.; et al. AI-driven cognitive telerehabilitation for stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1636017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liscano, Y.; Bernal, L.M.; Rodríguez, M.; Diaz Vallejo, J.A. Effectiveness of AI-assisted digital therapies for post-stroke aphasia rehabilitation: A systematic review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Cho, S.; Baek, D.; Bang, H.; Paik, N. Upper extremity functional evaluation by fugl-meyer assessment scoring using depth-sensing camera in hemiplegic stroke patients. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shull, P.B.; Jiang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, X. Hand gesture recognition and finger angle estimation via wrist-worn modified barometric pressure sensing. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2019, 27, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassbender, K.; Walter, S.; Grunwald, I.Q.; Merzou, F.; Mathur, S.; Lesmeister, M.; Kappel, A.; Weber, R.; Müller, C.; Schmidt, D.; et al. Prehospital stroke management in the thrombectomy era. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, K.B. Non-invasive sensor technology for prehospital stroke diagnosis: Current status and future directions. Int. J. Stroke 2019, 14, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.; Dreyer, R.P.; Murugiah, K.; Ranasinghe, I. Contemporary prehospital emergency medical services response times for suspected stroke in the United States. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2016, 20, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, C.P.; Sauvageau, E.; Snyder, K.V.; Fargen, K.M.; Arthur, A.S.; Turner, R.D.; Kan, P.; Levy, E.I.; Mocco, J.; Rasmussen, P.A.; et al. The VITAL study and overall pooled analysis with the VIPS non-invasive stroke detection device. J. NeuroInterventional Surg. 2018, 10, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebinger, M.; Siegerink, B.; Kunz, A.; Wendt, M.; Weber, J.E.; Schwabauer, E.; Malzahn, U.; Heuschmann, P.U.; Fiebach, J.B.; Endres, M.; et al. Association between dispatch of mobile stroke units and functional outcomes among patients with acute ischemic stroke in Berlin. JAMA 2021, 325, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, S.W.; Barrett, K.M.; Freeman, W.D.; Demaerschalk, B.M. Telemedicine-enabled ambulances and mobile stroke units for prehospital stroke management. J. Telemed. Telecare 2022, 28, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shlobin, N.A.; Baig, A.A.; Waqas, M.; Rai, A.T.; Turk, A.S.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Levy, E.I.; Mocco, J.; Nogueira, R.G.; Zaidat, O.O.; et al. Artificial intelligence for large-vessel-occlusion stroke: A systematic review. World Neurosurg. 2022, 159, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viz.ai. Viz.ai Granted De Novo FDA Clearance for First Artificial Intelligence Triage Software; PR Newswire: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- RapidAI. RapidAI Receives FDA Clearance of Rapid LVO; RapidAI Press Release: Golden, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brainomix. Brainomix Receives FDA Clearance for Its Flagship Stroke AI Imaging Software (e-ASPECTS); Brainomix Newsroom: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Avicenna.AI. Avicenna.AI Secures FDA Clearance for Two Healthcare AI Solutions Including CINA-ASPECTS; PR Newswire: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aidoc. Aidoc Secures FDA Clearance for AI Stroke Software Detecting Large Vessel Occlusion on CTA; AuntMinnie.com: Arlington, VA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.auntminnie.com/imaging-informatics/artificial-intelligence/article/15625031/aidoc-secures-fda-clearance-for-ai-stroke-software (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Methinks Software. FDA Clears AI Software Tool for Automated Detection of LVOs from CT Angiography (Methinks CTA Stroke); Practical Neurology: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Iosa, M.; Paolucci, S.; Antonucci, G.; Ciancarelli, I.; Morone, G. Application of an Artificial Neural Network to Identify the Factors Influencing Neurorehabilitation Outcomes of Patients with Ischemic Stroke Treated with Thrombolysis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagnini, S.; Arienti, C.; Patrini, M.; Liuzzi, P.; Mannini, A.; Carrozza, M.C. Machine learning methods for functional recovery prediction and prognosis in post-stroke rehabilitation: A systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishi, H.; Oishi, N.; Ishii, A.; Ono, I.; Ogura, T.; Sunohara, T.; Chihara, H.; Fukumitsu, R.; Okawa, M.; Yamana, N.; et al. Predicting Clinical Outcomes of Large Vessel Occlusion Before Mechanical Thrombectomy Using Machine Learning. Stroke 2019, 50, 2379–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Janabi, O.M.; El Refaei, A.; Elgazzar, T.; Mahmood, Y.M.; Bakir, D.; Gajjar, A.; Alateya, A.; Jha, S.K.; Ghozy, S.; Kallmes, D.F.; et al. Current Stroke Solutions Using Artificial Intelligence: A Review of the Literature. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Powers, W.J.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Ackerson, T.; Adeoye, O.M.; Bambakidis, N.C.; Becker, K.; Biller, J.; Brown, M.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Hoh, B.; et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019, 50, e344–e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budhu, J.A.; Anderson, N.; Branson, C.; Choudhury, A.; Du, R.; Essig, M.; Garg, N.; Gaynor, E.; Greenberg, B.; Johnson, C.; et al. Health equity considerations in the age of artificial intelligence. Neurology 2025, 105, e214356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref # | Author | Date | Study Design | Topic | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [80] | Ceklic E, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective observational cohort study | EMS routing optimization | B-NR |

| [81] | Rava RA, et al. | 2021 | Retrospective modeling study | EMS routing optimization | B-NR |

| [82] | Ramos A, et al. | 2021 | Narrative review | EMS stroke recognition | C-EO |

| [83] | Wasselius J, et al. | 2021 | Prospective diagnostic study | EMS stoke recognition | B-NR |

| [84] | Scholz ML, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective modeling study | EMS stroke recognition | B-NR |

| [85] | Van Stigt MN, et al. | 2013 | Prospective diagnostic study | EMS stroke recognition | B-NR |

| [86] | Caceres JA, et al. | 2013 | Retrospective observational cohort study | EMS stroke recognition | B-NR |

| [87] | Oostema JA, et al. | 2018 | Retrospective observational study | EMS stroke recognition | B-NR |

| [88] | Jia J, et al. | 2017 | Retrospective observational study | EMS stroke recognition | B-NR |

| [89] | Pottle, J | 2019 | Narrative review | EMS training | C-EO |

| [12] | Wollcott ZC, et al. | 2024 | Expert commentary | EMS workflow optimization | C-EO |

| [90] | Bat-Erdine BO, et al. | 2021 | Narrative review | Patient stroke recognition | C-EO |

| [91] | Kim HS, et al. | 2015 | Observational diagnostic accuracy study | Patient stroke recognition | C-LD |

| [92] | Raychey RI, et al. | 2023 | Proof of concept study | Patient stroke recognition | C-LD |

| Ref # | Author | Year | Study Design | Topic | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [93] | Figurell ME, et al. | 2023 | Retrospective workflow implementation study | Workflow optimization | B-NR |

| [94] | Gunda B, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective workflow implementation study | Workflow optimization | B-NR |

| [95] | Field NC, et al. | 2023 | Retrospective workflow implementation study | Workflow optimization | B-NR |

| [96] | Devlin T, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective multicenter cohort study | Workflow optimization | B-NR |

| [97] | Hassan AE, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective observational study | Workflow optimization | B-NR |

| [31] | Herzog L, et al. | 2023 | Prospective prognostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [33] | Zhang H, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective prognostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [34] | Velagapudi L, et al. | 2021 | Retrospective prognostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [35] | Wang X, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective prognostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [32] | Liu Y, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective predictive model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [28] | van Os HJA, et al. | 2018 | Registry prognostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [29] | Heo J, et al. | 2019 | Retrospective prognostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [30] | Jung HS, et al. | 2024 | Prospective prognostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [11] | Koska IO, et al. | 2023 | Narrative review | Advanced imaging interpretation | C-EO |

| [32] | Liu Y, et al. | 2024 | Narrative review | Advanced imaging interpretation | C-EO |

| [14] | Chandrabhatla AS, et al. | 2023 | Narrative review | Advanced imaging interpretation | C-EO |

| [64] | Ryu WS, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective diagnostic model study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [66] | Christiansen SD, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective diagnostic model study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [79] | Savage CH, et al | 2024 | Prospective observational diagnostic study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [98] | Olive-Gadea M, et al. | 2020 | Retrospective diagnostic imaging study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [99] | McLouth J, et al. | 2021 | Retrospective diagnostic imaging study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [100] | Yahav-Dovrat A, et al. | 2021 | Retrospective diagnostic imaging study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [101] | Schlossman J, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective diagnostic imaging study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [102] | Luijten SPR, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective diagnostic imaging study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [103] | Cimflova P, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective diagnostic imaging study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [104] | Bathla G, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective diagnostic imaging study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [105] | Adamou A, et al. | 2023 | Systematic review | Advanced imaging interpretation | C-EO |

| [106] | Wolff L, et al. | 2021 | Retrospective diagnostic imaging study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [107] | Lee SJ, et al. | 2024 | Prospective diagnostic imaging study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [108] | Jiang B, et al. | 2025 | Systematic review | Advanced imaging interpretation | C-EO |

| [109] | Alwood BT, et al. | 2024 | Multicenter retrospective diagnostic study | Advanced imaging interpretation | B-NR |

| [15] | Wang Z, et al. | 2024 | Systematic review | General | C-EO |

| [16] | Melo S, et al. | 2025 | Scoping review | General | C-EO |

| [17] | Heeralal VT, et al. | 2025 | Narrative review | General | C-EO |

| [18] | Heo J. | 2025 | Scoping review | General | C-EO |

| [36] | Colangelo G, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [37] | Gao Y, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [38] | Lip GYH, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [39] | Vodencarevic A, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [40] | Han L, et al. | 2019 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [41] | Chen B, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [42] | Chao CJ, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [43] | Lin L, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [44] | Araki T, et al. | 2017 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [45] | Bai P, et al. | 2020 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [46] | Sue SS, et al. | 2023 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [21] | Chen YF, et al. | 2023 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [63] | Rabinstein AA, et al. | 2021 | Retrospective predictive model study | Predictive analytics | B-NR |

| [65] | Heo J, et al. | 2023 | Retrospective multicenter diagnostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [67] | Li X, et al. | 2020 | Retrospective diagnostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [69] | Lu X, et al. | 2024 | Retrospective diagnostic/prognostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [70] | Heo J, et al. | 2022 | Retrospective prognostic model study | Prognostication | B-NR |

| [110] | Ali F, et al. | 2020 | Narrative review | Telemedicine optimization | C-EO |

| [111] | Mohamed A, et al. | 2023 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Telemedicine optimization | C-EO |

| Ref # | Author | Year | Study design | Topic | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [112] | Vélez-Guerrero MA, et al. | 2021 | Narrative review | Assistive robotics/exoskeletons | C-EO |

| [113] | Várkuti B, et al. | 2012 | Prospective interventional cohort | Brain-computer interfacing devices | B-NR |

| [114] | Cervera MA, et al. | 2018 | Meta analysis of RCTs | Brain-computer interfacing devices | C-EO |

| [115] | Bundy DT, et al. | 2017 | Prospective interventional cohort study | Brain-computer interfacing devices | B-NR |

| [116] | Mrachacz-Kersting N, et al. | 2016 | Prospective interventional cohort study | Brain-computer interfacing devices | B-NR |

| [117] | Senadheera I, et al. | 2024 | Scoping review | General | C-EO |

| [118] | Buetefisch CM | 2015 | Narrative review | General | C-EO |

| [119] | Dobkin A | 2024 | Scoping review | General | C-EO |

| [120] | Choo YJ, et al. | 2022 | Narrative review | General | C-EO |

| [121] | Sale P, et al. | 2018 | Prospective observational study | General | B-NR |

| [122] | Kim S, et al. | 2025 | Multicenter RCT | Tele-rehabilitation | B-R |

| [123] | Liscano Y, et al. | 2025 | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Tele-rehabilitation | B-R |

| [124] | Kim W, et al. | 2016 | Prospective observational validation study | Wearable sensor technology | B-NR |

| [125] | Shull PB, et al. | 2019 | Prospective sensor validation study | Wearable sensor technology | B-NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sorkin, G.C.; Caffes, N.M.; Shank, J.P.; Hershey, J.L.; Knaub, D.E.; Krebs, J.C.; Niazi, M.H. Current State of the Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Stroke: A Literature Review. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16020173

Sorkin GC, Caffes NM, Shank JP, Hershey JL, Knaub DE, Krebs JC, Niazi MH. Current State of the Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Stroke: A Literature Review. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(2):173. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16020173

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorkin, Grant C., Nicholas M. Caffes, John P. Shank, James L. Hershey, Dana E. Knaub, Jillian C. Krebs, and Muhammad H. Niazi. 2026. "Current State of the Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Stroke: A Literature Review" Brain Sciences 16, no. 2: 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16020173

APA StyleSorkin, G. C., Caffes, N. M., Shank, J. P., Hershey, J. L., Knaub, D. E., Krebs, J. C., & Niazi, M. H. (2026). Current State of the Clinical Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Stroke: A Literature Review. Brain Sciences, 16(2), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16020173