4. Discussion

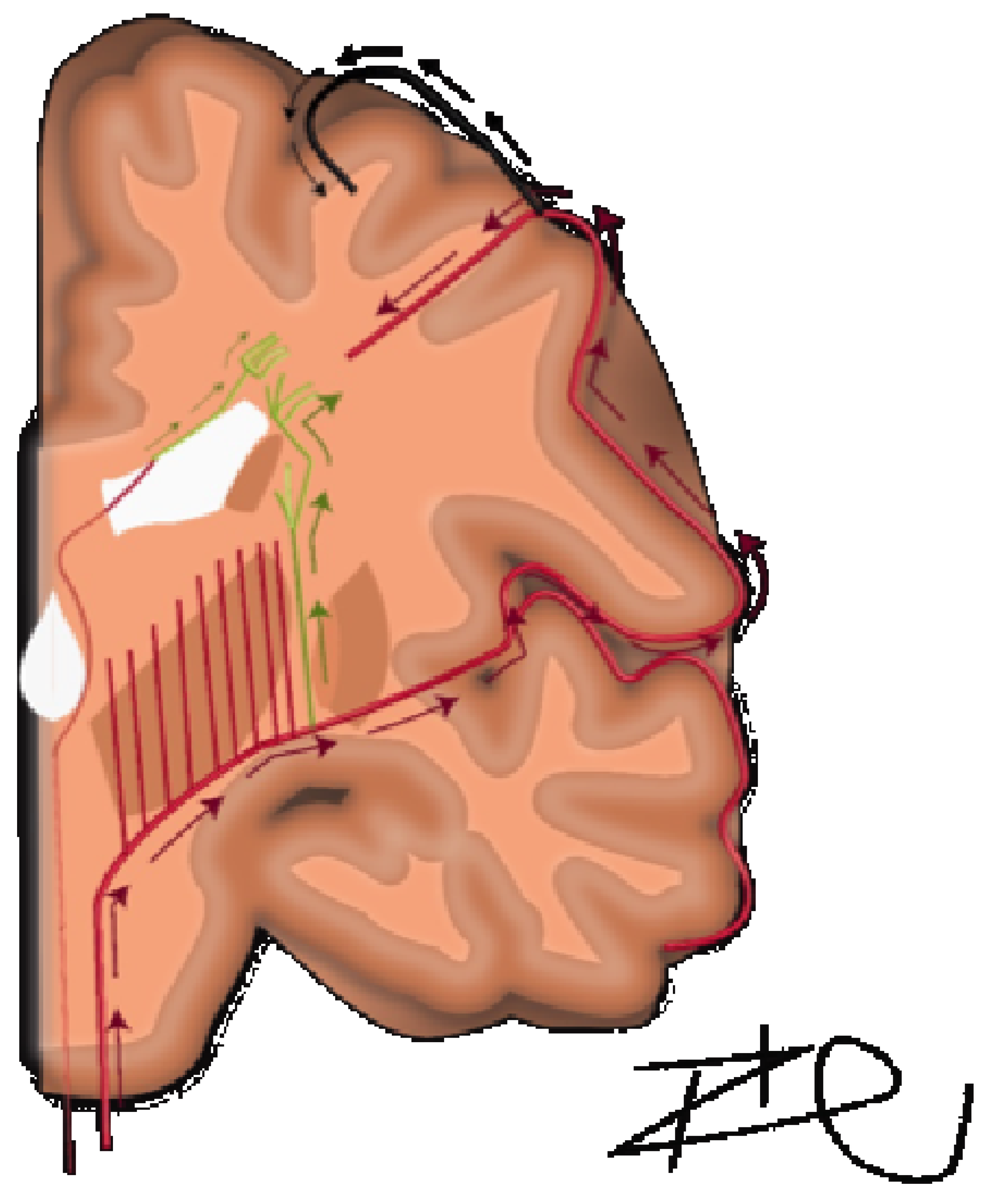

A detailed understanding of the centrum semiovale requires a brief review of its anatomical makeup, which was comprehensively described by Bogousslavsky and Regl in 1992 [

6]. They discussed four different vascular territories: (1) the territory of the deep perforators (lateral and medial lenticulostriate, anterior choroidal, Hubner, anterior lenticulostriate and thalamostriate), (2) perforating branches of the superficial branches of the MCA, (3) junctional territories between deep and superficial territories of MCA, or (4) combined or extended subcortical infarcts. In terms of volume supplied, the predominant territory was the medullary arteries of the middle cerebral artery. The course of these arteries are relatively long and serpiginous and have been further detailed by Van den Bergh [

7,

8]. The middle cerebral medullary arteries must first reach the pial surface before beginning a 90-degree centripetal turn towards the lateral ventricles, spanning approximately 2–5 cm [

9]. This is exaggerated in cases of chronic hypertension, in which vasculature demonstrates increased tortuosity [

9]. There is a characteristic lack of arborization in centripetal, pre-periventricular arteries and thus function as terminal vessels without the contingency of collateral supply in times of decreased perfusion [

10]. In contrast, subcortical U-fibers have dual supply with more superficial arterial vasculature and are characteristically spared from these white matter lesions in leukoaraiosis. Distinctly, in the immediate periventricular space, periventricular white matter is supplied by branches of the choroidal arteries and distal terminal lenticulostriate vessels traveling ventriculofugally (

Figure 1) [

8,

10,

11]. In the context of this anatomical makeup, there is a physiological mechanism implied for the lack of cerebrovascular reserve in the centrum semiovale.

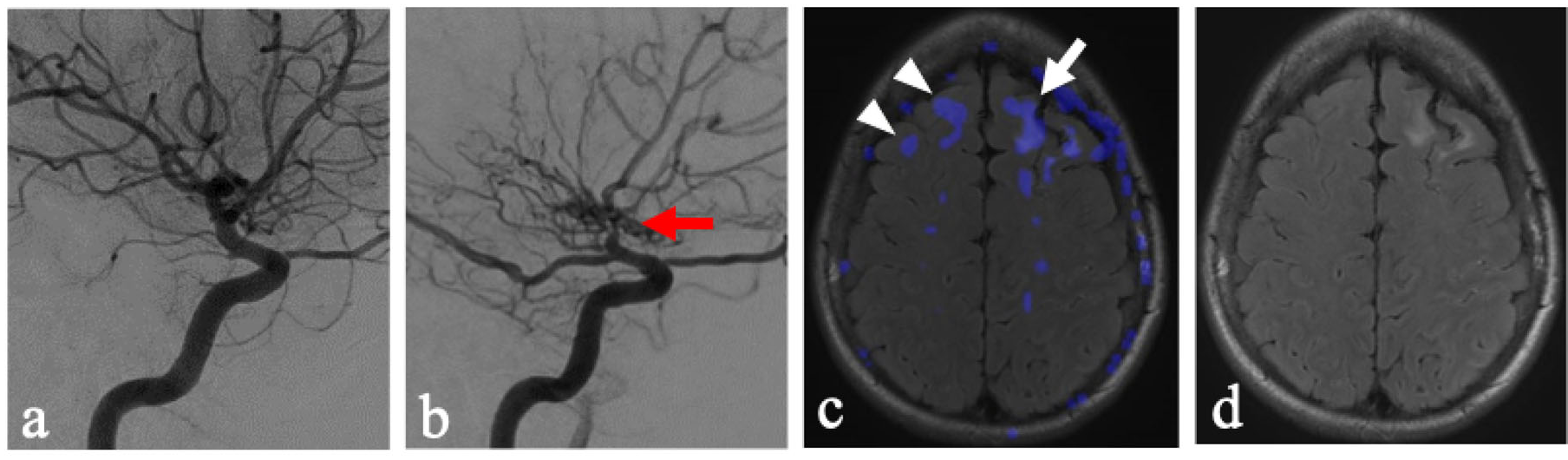

Our data demonstrated that in cerebral hemispheres without significant flow limitations (non-flow-limited hemispheres or NFLH), increased physiological demand from the acetazolamide challenge resulted in a physiological steal phenomenon, away from white matter structures of the centrum semiovale. These findings suggest the presence of an intrinsically vulnerable cerebrovascular reserve in this region, even without proximal flow-limiting disease. Furthermore, the severity of steal in the NFLH demonstrated a strong relationship with the degree of T2 hyperintensities in the NFLH.

The findings presented suggest that inherent physiological vulnerability may play a role in the ubiquity of leukoaraiosis in this region and demand ischemia to be a key factor in the formation of T2 hyperintensities. While chronic hypertension and microangiopathy are often discussed as the precursor vasculature changes within the deep white matter tracts that, in turn, cause decreased vascular reserve and areas of leukoaraiosis [

12], the inherent dynamic physiological vulnerabilities of the vasculature supplying the centrum semiovale may play a key role. This is supported by findings of steal in the centrum semiovale in the side without flow-limiting stenosis (

Figure 2). These findings suggest an inherent physiological vulnerability of these regions to possible fluctuations in hemodynamics.

There is a paucity of clinical research investigating the pathophysiology of cerebrovascular reserve within the centrum semiovale. Martson et al. investigated 85 normal subjects under acetazolamide-augmented MRI and found hemodynamic changes after acetazolamide augmentation were less prominent in places of white matter hyperintensities when compared to normal-appearing white matter and concluded “a change in the hemodynamic status is present within the WMH, making these areas more likely to be exposed to transient ischemia inducing myelin rarefaction” [

13]. This was recently supported by research correlating areas of poor cerebrovascular reserve with increased white matter hyperintensities, lacunar infarctions, and microhemorrhages [

14]. Further support for altered hemodynamics was found in a study of vasoreactivity in multiple sclerosis, in which the vascular territory supplying the centrum semiovale was relatively limited in its autoregulation compared to surrounding territories in both MS patients as well as the controls [

15].

One reason for the decreased vascular reserve may lie in the differential vascular responses to perfusion pressures at different vascular calibers. The cross-sectional diameter of the medullary arteries supplying the white matter is typically consistent until it approaches the lateral ventricle, and ranges from 100 to 200 μm [

10]. Various human and animal studies suggest that smaller arterioles have a significant role in vascular autoregulation but are primarily activated in intermediate-to-severe levels of hypoperfusion [

16,

17,

18]. Thus, while territories with smaller diameter arterioles demonstrate profound dilatation during severe hypotensive episodes [

19] and protect against areas of necrosis and cavitation, they may still be vulnerable to diffuse rarefaction from episodes of less severe ischemia.

Perhaps even more critical is the length of the arterioles that supply the centrum semiovale. These consist of long medullary penetrating arterioles arising from the proximal MCA and are the longest parenchymal arterioles in the brain. Due to their length, these vessels demonstrate significantly higher flow resistance [

20]. Therefore, there may be baseline vasodilatation existing in the normal physiological state. Thus, increased demand in these vessels results in limited additional vasodilatation and cerebrovascular reserve. In contrast, the shorter, cortical arterioles may demonstrate less baseline resistance, increased vasodilatation on demand and greater cerebrovascular reserve. Animal studies performed by Symon et al. [

21] demonstrated episodes of zero blood flow in white matter territories at times of reduced perfusion pressures with the preservation of flow in the gray matter at the same degree of perfusion. This led the authors to conclude that “white matter possesses a less sensitive and effective regulatory mechanism than that in gray matter”. Furthermore, a study of newborn dogs demonstrated the preferential preservation of CBF in the gray matter but not the periventricular and occipital white matter [

22].

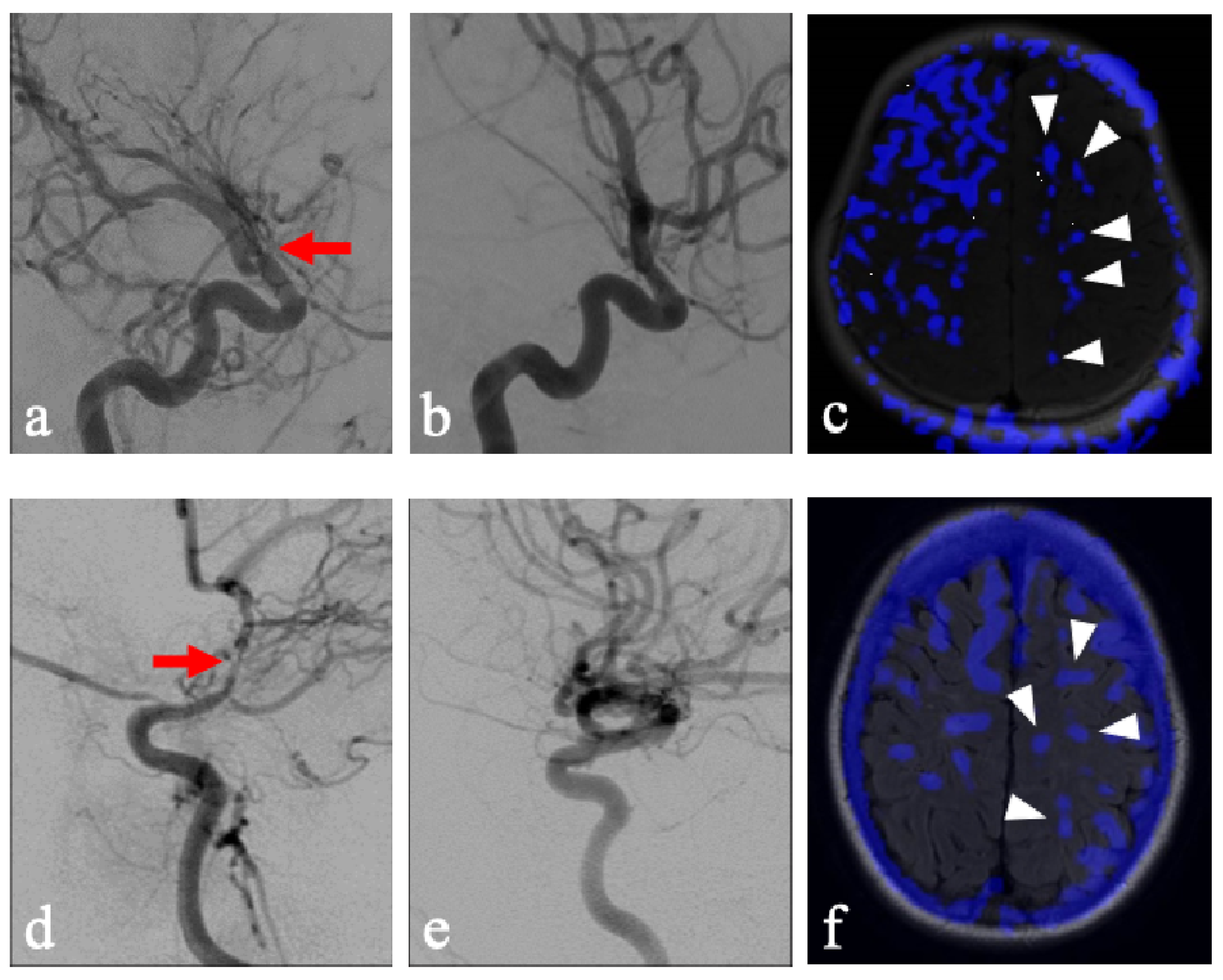

A few considerations must be observed in the current methodology. Patients with chronic unilateral steno-occlusive disease may have developed compensatory contralateral contributions from the NFLH to the FLH via the Circle of Willis. Additionally, the NFLH in these patients may also demonstrate decreased overall reserve due to exposure to the same vascular risk factors which lead to disease on the FLH. Lastly, acetazolamide as a stressor may be considered too extreme of a vasodilator when compared to states of physiologically increased demand. Quantitative generalizability is therefore limited in this evaluation as various factors may exaggerate steal phenomenon in our patient population. However, while these may exaggerate the degree of steal in NFLH, it nonetheless uncovers a key compensatory mechanism inherent to areas that have demonstrated a propensity for leukoaraiosis. Particularly illustrative cases of this phenomenon include pediatric patients without documentation of chronic hypertension and who were unlikely to have long-term sequalae or compensation of hypertensive pathology, who were found to display this pattern of steal after acetazolamide administration (

Figure 3). This study lays the groundwork for comparison with healthy controls, which would provide more definitive analysis.

For both the evaluation of WMH and vascular steal, we utilized a semi-quantitative, observer dependent scoring system: either the Fazekas scale for WMH or an adopted model for steal. Alternative approaches for analysis exist, such as quantitative ΔCBF analysis or ROI-based measurements. Such approaches have been utilized by the authors evaluating pharmaceutical reactivity or correlation with angiographic findings [

23,

24]. In this particular context, the Fazekas score allows the utilization of a well-understood and clinically ubiquitous scoring system. Additionally, the Fazekas score has demonstrated moderate-to-good inter-rater reliability in cross-sectional evaluation [

25].

The ability to create subtraction images from ASL CBF maps, which were acquired within the same acquisition, allowed for mapping of augmentation and steal. This provided both qualitative displays of subtle perfusion changes as well as fused overlay on anatomic images (

Figure 2c). This allowed for the development of a modified Fazekas score. However, the applicability of this methodology could be limited in other imaging modalities, such as SPECT, DSC perfusion MRI, or CT. The generalizability of these methods in various modalities would warrant future research and may be institutionally dependent. Additionally, while the Fazekas score has demonstrated good inter-rater reliability, such inter-rater reliability for the modified scoring system is not yet assessed.

We utilized the ASCVD score as a surrogate for vascular health. In our study, we found no statistical significance between the ASCVD score and the amount of cerebrovascular steal or T2 hyperintensities. However, there were several limitations in correlative analysis. Primarily, the calculation utilized in ASCVD calculation is optimized to predict the 10-year risk of an atherosclerotic cardiovascular event, which may have similar etiologies to cerebrovascular events but different weighting of individual variables. Also, variables specific to cerebrovascular disease would not be included in this analysis. Additionally, the data acquisition was retrospective in nature and therefore not standardized. The ASCVD risk assessment is recommended to be performed prior to starting therapy with subsequent recalculations throughout the course of treatment [

26]. However, patients obtained an acetazolamide challenge MRI throughout various stages of their cardiovascular risk factor management. Lastly, several patients were not able to be included in the evaluation due to the age restriction of 40–75 or missing clinical data. These limitations may have resulted in nonsignificant findings and a more targeted scoring system of cerebrovascular health, which would be a beneficial topic of future research.

Additionally, technical limitations include the utilization of 8-channel coils for MR imaging. Using more recently available higher channel coils would produce better signal-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution. This could improve statistical significance through the detection of smaller perfusion changes and may allow for a more specific anatomic delineation of white matter tracts. Also, the reproducibility of augmentation outcomes under repeated acetazolamide evaluations was not assessed, and thus, reproducibility cannot be established.