AI-Driven Prediction of Possible Mild Cognitive Impairment Using the Oculo-Cognitive Addition Test (OCAT) †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Equipment

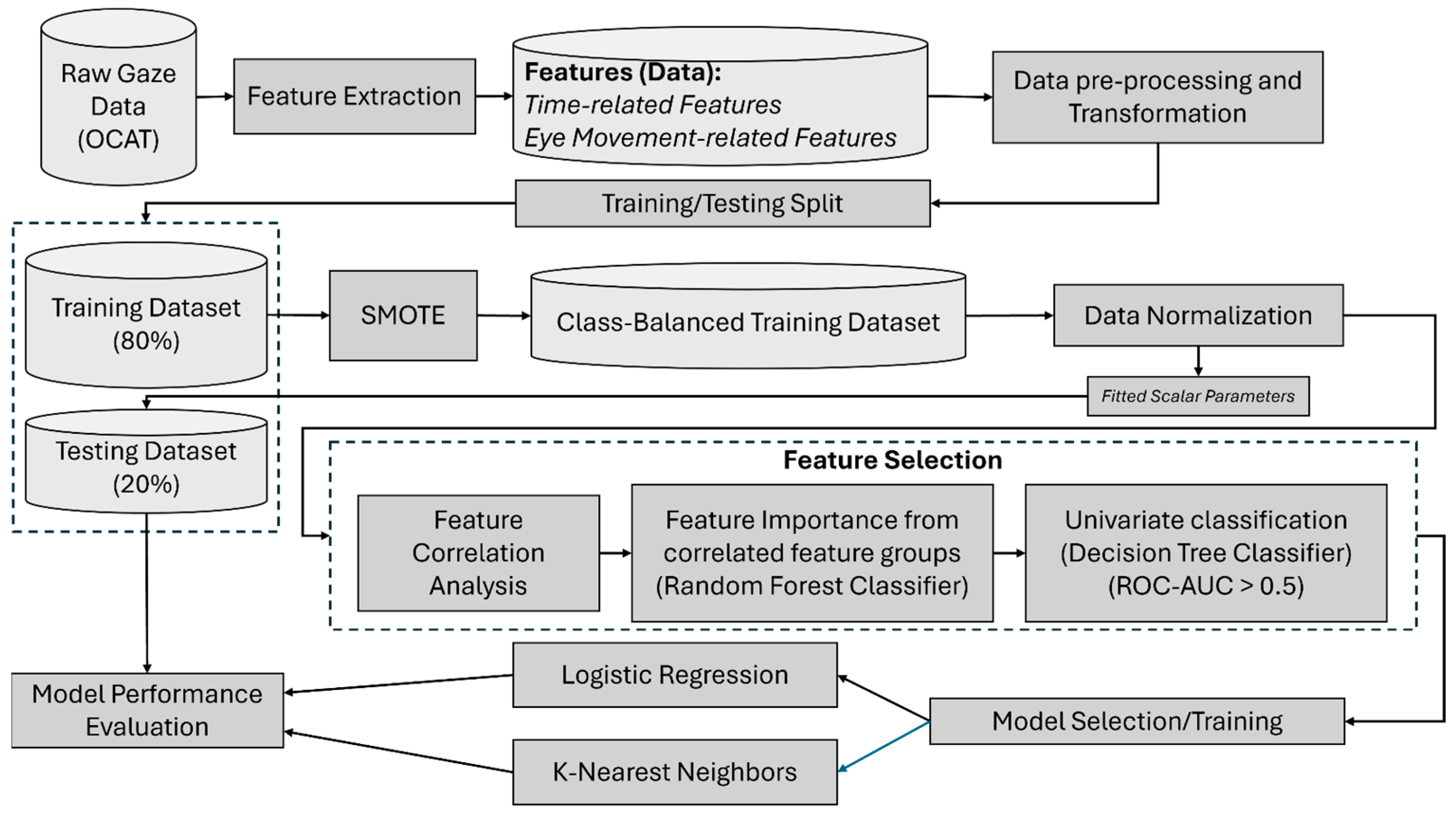

2.3. Data Processing and Feature Extraction

2.4. Feature Selection

2.5. Learning Models and Analysis Procedure

3. Results

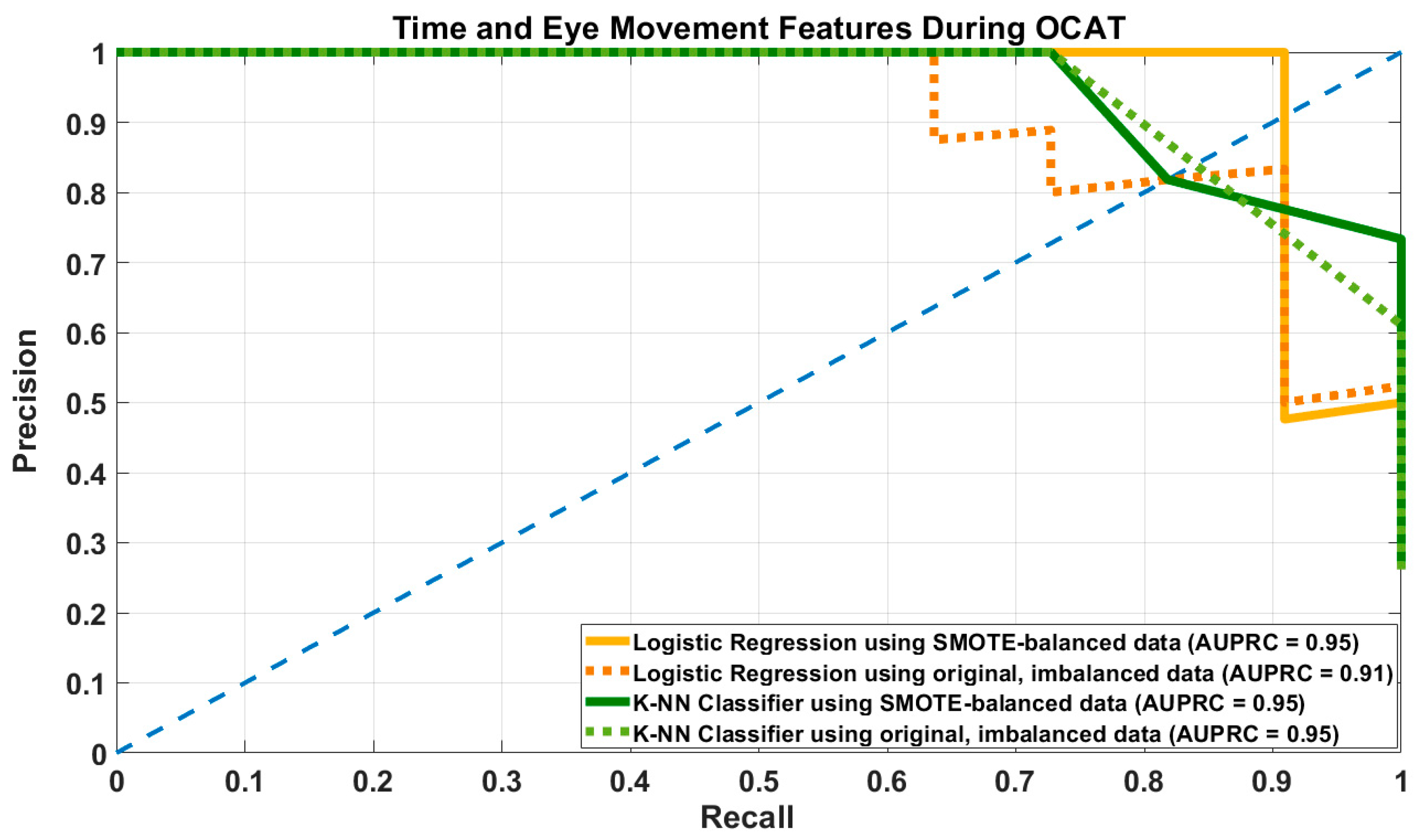

3.1. Results of Prediction Models Using Time and Eye Movement-Related Features

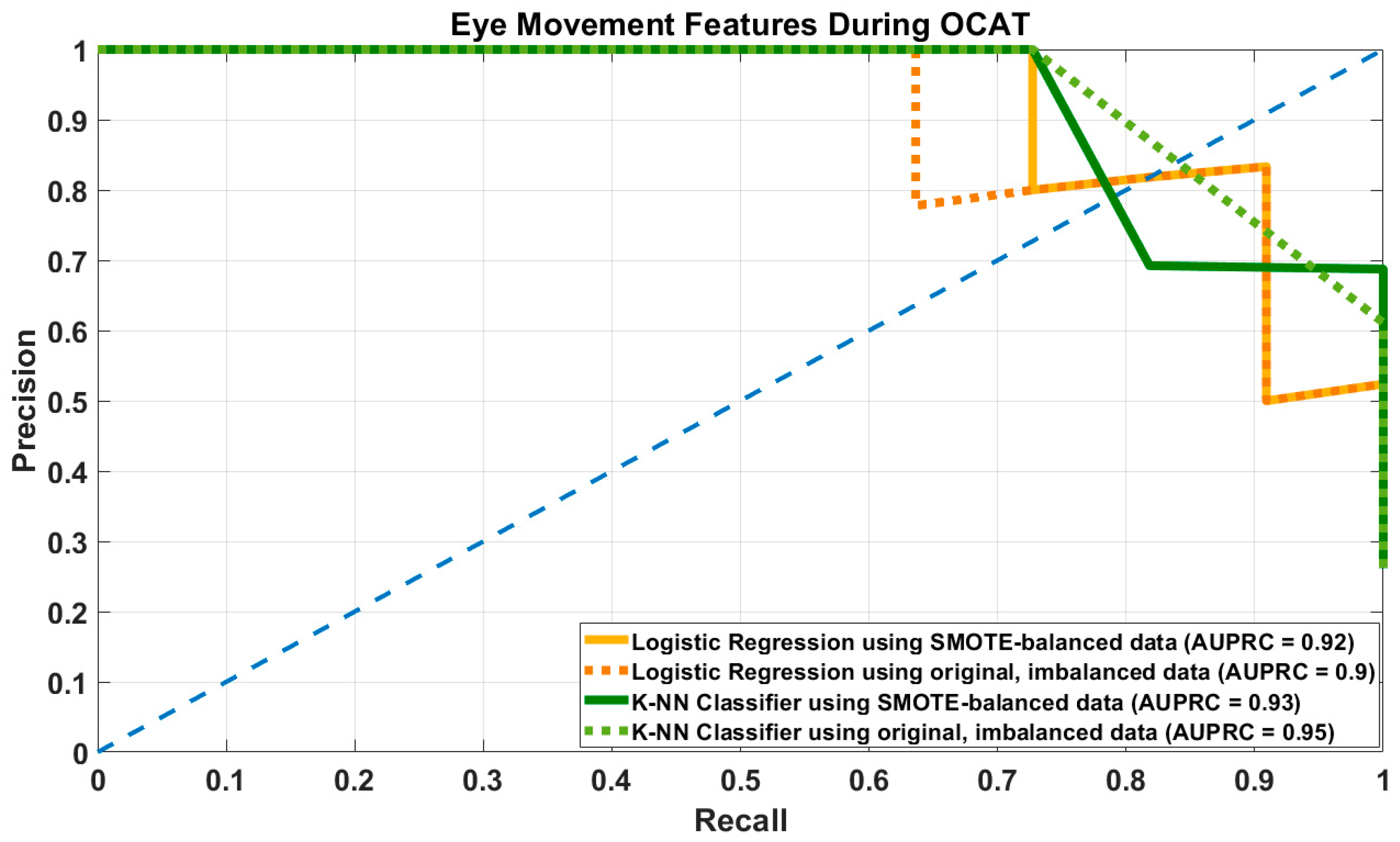

3.2. Results of Prediction Models Using Eye Movement-Related Features

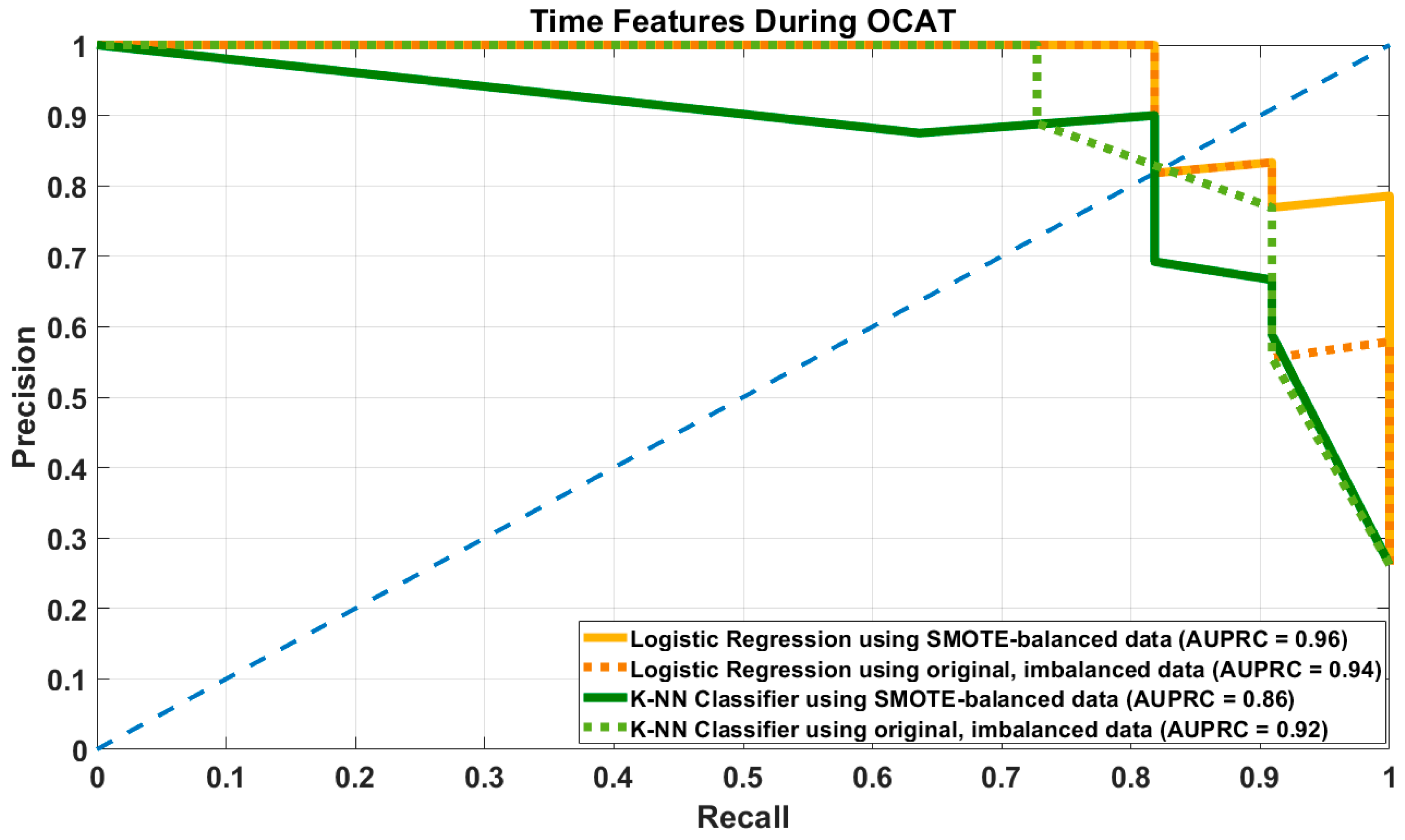

3.3. Results of Prediction Models Using Time-Related Features

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MCI | Mild cognitive impairment |

| OCAT | Oculo-Cognitive Addition Test |

| PMCI | Possible Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| CN | Cognitive Normal |

Appendix A

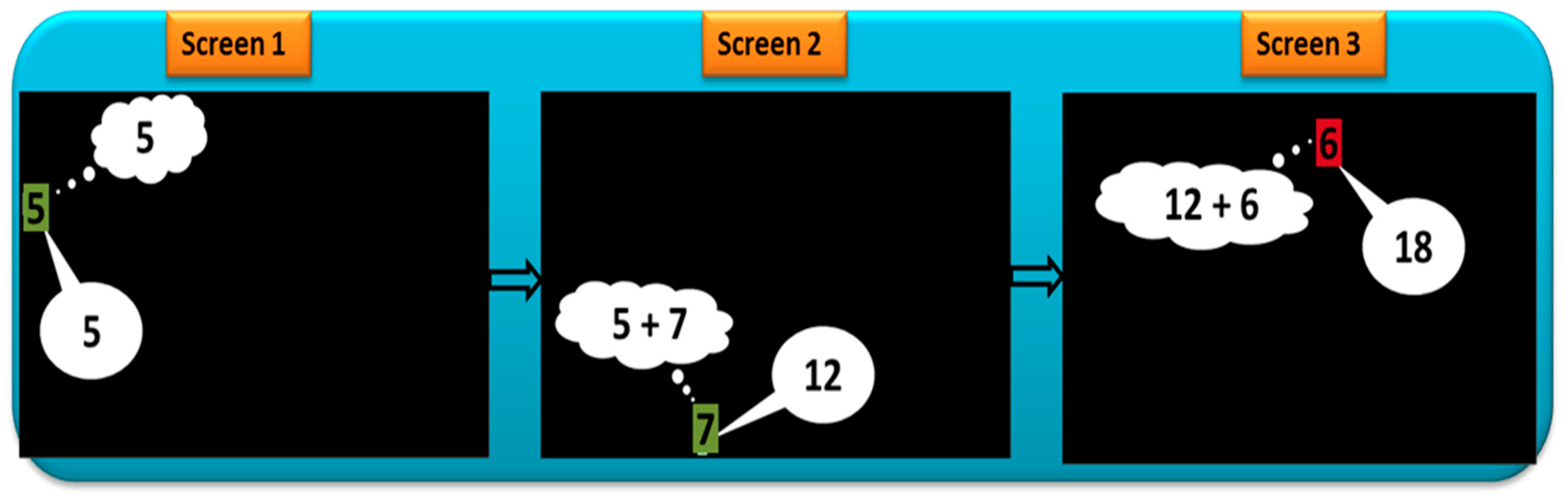

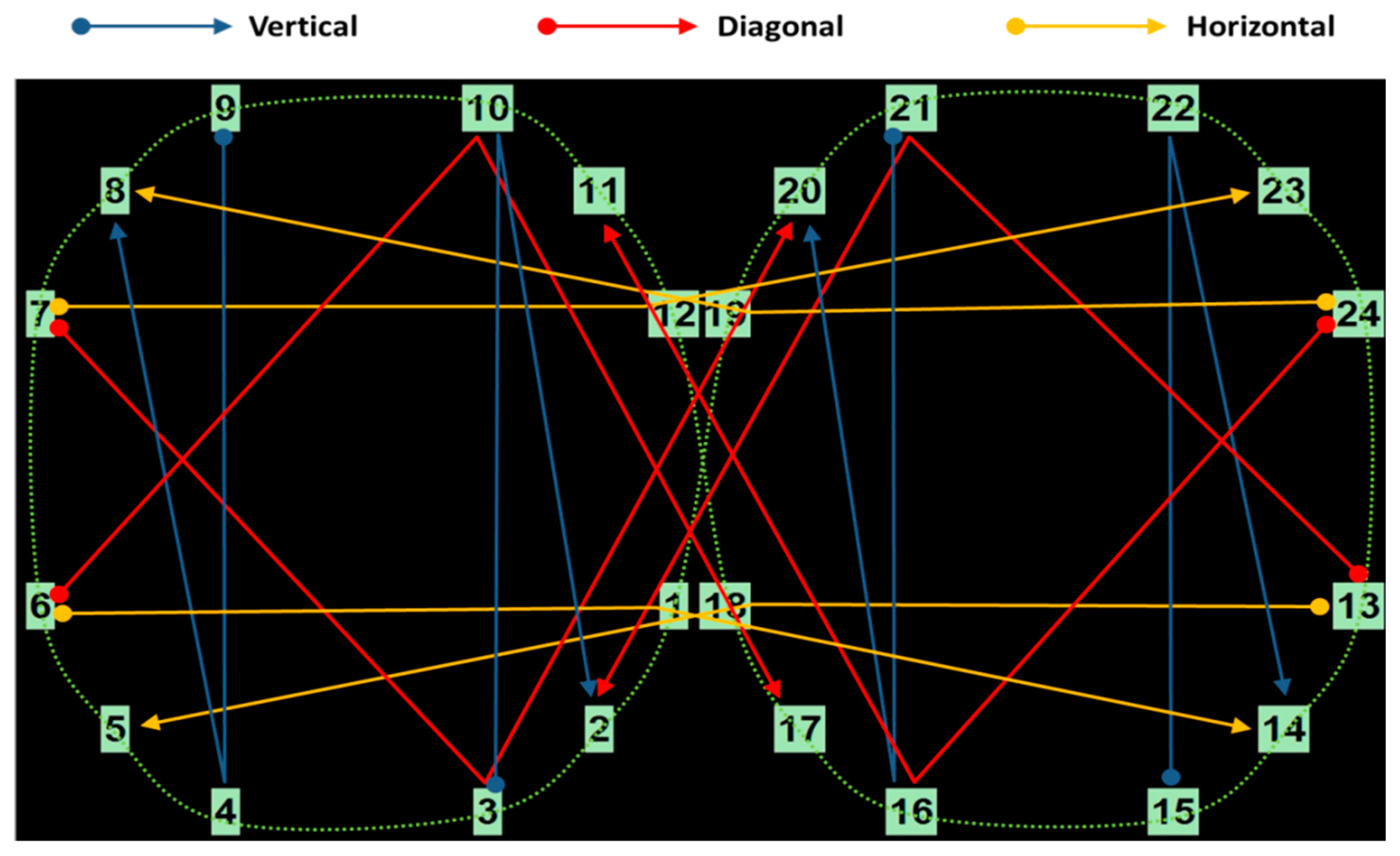

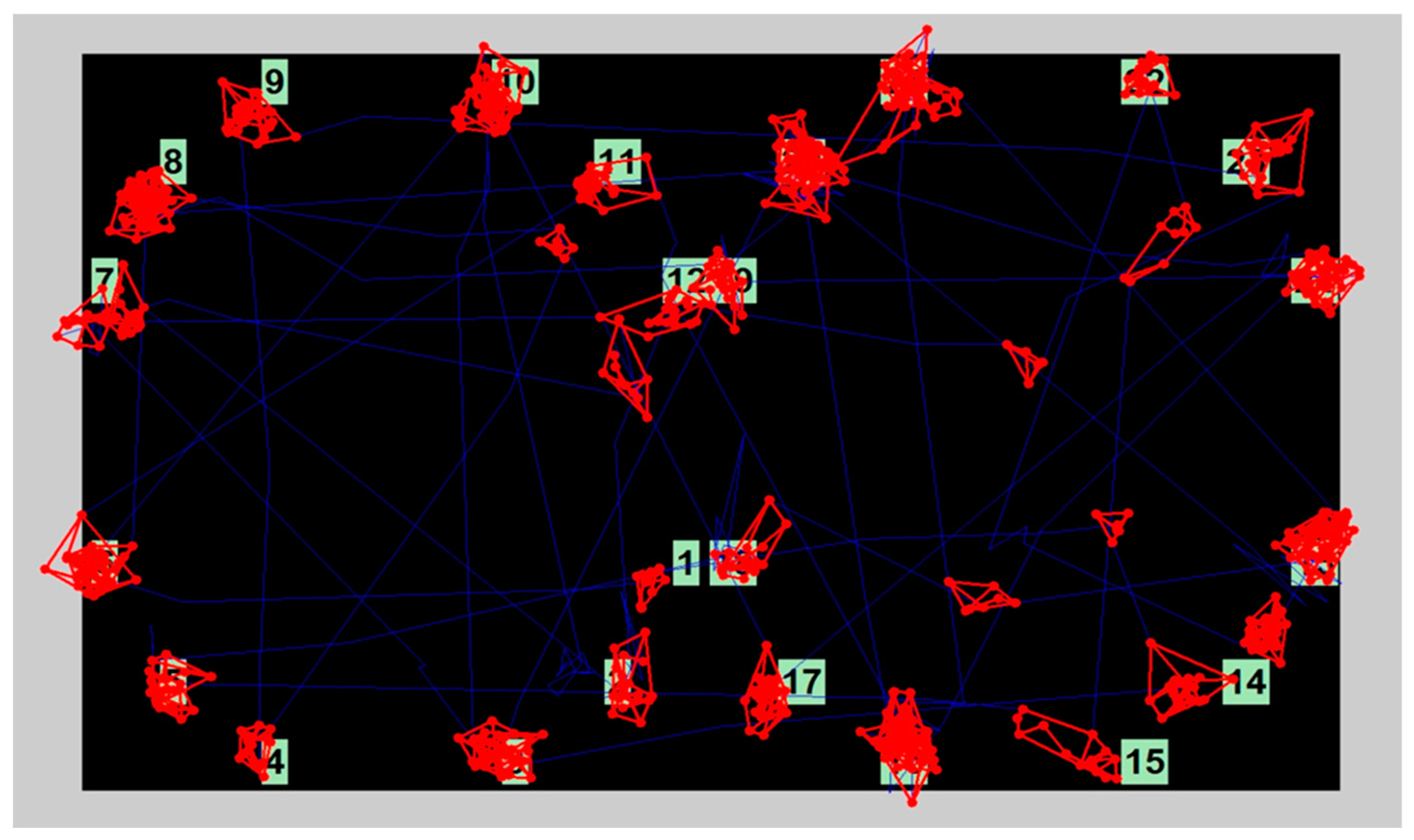

Oculo-Cognitive Addition Test

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Eye Movement Features

Appendix B.2. Data Related to Fixations

Appendix B.3. Data Related to Saccades

Appendix B.4. Data Related to Blink and Pupillary Dynamics

References

- Anderson, N. State of the science on mild cognitive impairment (MCI). CNS Spectrums 2019, 24, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, N.; Li, X.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Shi, N. Diagnosis and treatment for mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 719849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.; Smith, G.; Waring, S.; Ivnik, R.; Tangalos, E.; Kokmen, E. Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Arch. Neurol. 1999, 56, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.; Lopez, O.; Armstrong, M.; Getchius, T.; Ganguli, M.; Gloss, D.; Gronseth, G.; Marson, D.; Pringsheim, T.; Day, G.; et al. Practice guideline update summary: Mild cognitive impairment. Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2018, 90, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Int. Med. 2004, 256, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarsland, D.; Brønnick, K.; Larsen, J.; Tysnes, O.; Alves, G. Cognitive impairment in incident, untreated Parkinson disease. Neurology 2009, 72, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteau, E.; Dupre, N.; Langlois, M.; Jean, L.; Thivierge, S.; Provencher, P.; Simard, M. Mattis Dementia Rating Scale 2: Screening for MCI and dementia. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2011, 26, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, C.; Caramelli, P.; Nitrini, R. The Dementia Rating Scale (DRS) in the diagnosis of vascular dementia. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2007, 3, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marson, D.; Dymek, M.; Duke, L.; Harrell, L. Subscale validity of the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1997, 12, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, D.; Manzanares, C.; Zola, M.; Buffalo, E.; Agichtein, E. Detecting cognitive impairment by eye movement analysis using automatic classification algorithms. J. Neurosci. Methods 2011, 201, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosimann, U.; Müri, R.; Burn, D.; Felblinger, J.; O’Brien, J.; McKeith, I. Saccadic eye movement changes in Parkinson’s disease dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain 2005, 128, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, N.T.; Lange, A.; Rentz, D.; Buffalo, E.; Clopton, P.; Zola, S. Web Camera Based Eye Tracking to Assess Visual Memory on a Visual Paired Comparison Task. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalafatis, C.; Khaligh Razavi, S.-M. F3-01-03: The Integrated Cognitive Assessment-Employing Artificial Intelligence for the Detection of Cognitive Impairment. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 15, P864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, G.; Cevette, M.J.; Stepanek, J.; Brookler, K.H. Oculo-Cognitive Addition Testing. U.S. Patent No. 11,869,386 B2, 9 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, G.; Bogle, J.; Kleindienst, S.; Cevette, M.; Stepanek, J. Correlating multi-dimensional oculometrics with cognitive performance in healthy young adults. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2018, 2, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, G.; Hagen, K.; Cevette, M.; Stepanek, J. Oculo-Cognitive Addition Test: Quantifying Cognitive Performance During Variable Cognitive Workload Through Eye Movement Features. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 10th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI) 2022, Rochester, MN, USA, 11–14 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, G.; Bogle, J.; Cevette, M.; Stepanek, J. Discovering oculometric patterns to detect cognitive performance changes in healthy youth football athletes. J. Healthc. Inform. Res. 2019, 3, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Oh, S. Recording and interpretation of ocular movements: Saccades, smooth pursuit, and optokinetic nystagmus. Ann. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2023, 25, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Katz, L.; LaMantia, A.; McNamara, J.; Williams, S. (Eds.) Types of eye movements and their functions. In Neuroscience; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh, R.; Kennard, C. Using saccades as a research tool in the clinical neurosciences. Brain 2004, 127, 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brouwer, S.; Yuksel, D.; Blohm, G.; Missal, M.; Lefevre, P. What triggers catch-up saccades during visual tracking? J. Neurophysiol. 2002, 87, 1646–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liversedge, S.; Findlay, J. Saccadic eye movements and cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2000, 4, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejtz, K.; Duchowski, A.; Niedzielska, A.; Biele, C.; Krejtz, I. Eye tracking cognitive load using pupil diameter and microsaccades with fixed gaze. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegenthaler, E.; Costela, F.; McCamy, M.; Di Stasi, L.; Otero-Millan, J.; Sonderegger, A.; Groner, R.; Macknik, S.; Martinez-Conde, S. Task difficulty in mental arithmetic affects microsaccadic rates and magnitudes. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 39, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, B.; Biscaldi, M.; Gezeck, S. On the development of voluntary and reflexive components in human saccade generation. Brain Res. 1997, 754, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, W.; Sharpe, J. Saccadic eye movement dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. Neurol. 1986, 20, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, L.; Whicker, L.; Abel, L.; LF, D.O.; Traccis, S.; Grossniklaus, D. Saccadic latency measurements in dementia. Arch. Neurol. 1983, 40, 592–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Choe, J.; Noh, S.; Kim, J.; Han, J.; Kim, K. Exploring age-related changes in saccades during cognitive tasks in healthy adults. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1301318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bylsma, F.; Rasmusson, D.; Rebok, G.; Keyl, P.; Tune, L.; Brandt, J. Changes in visual fixation and saccadic eye movements in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1995, 19, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, K.; Yeh, S.; Chien, S. Assessing perceptual load and cognitive load by fixation-related information of eye movements. Sensors 2022, 22, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Jun, S.; Sung, J. Pupillometry as a window to detect cognitive aging in the brain. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 2024, 14, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kremen, W.; Panizzon, M.; Elman, J.; Granholm, E.; Andreassen, O.; Dale, A.; Gillespie, N.; Gustavson, D.; Logue, M.; Lyons, M.; et al. Pupillary dilation responses as a midlife indicator of risk for Alzheimer’s Disease: Association with Alzheimer’s Disease polygenic risk. Neurobiol. Aging 2019, 83, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladas, A.; Frantzidis, C.; Bamidis, P.; Vivas, A. Eye Blink Rate as a biological marker of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2014, 93, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, G.; Kingsbury, S.; Cevette, M.; Stepanek, J.; Caselli, R. Towards Early Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment: Predictive Analytics Using the Oculo-Cognitive Addition Test (OCAT). In Proceedings of the 17th International Joint Conference on Knowledge Discovery, Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management—KDIR, Marbella, Spain, 22–24 October 2025; pp. 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli, R.; Langlais, B.; Dueck, A.; Chen, Y.; Su, Y.; Locke, D.; Woodruff, B.; Reiman, E. Neurosychological decline up to 20 years before incident mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2020, 16, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, P.; Mohs, R. Memory Changes with Aging and Dementia. In Functional Neurobiology of Aging; Hof, P., Mobbs, C., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mast, B.; Gerstenecker, A. Screening Instruments and Brief Batteries for Dementia. In Handbook of Assessment in Clinical Gerontology, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 503–530. [Google Scholar]

- Rascovsky, K.; Salmon, D.; Hansen, L.; Galasko, D. Distinct cognitive profiles and rates of decline on the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale in autopsy-confirmed frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2008, 14, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattis, S. Mental Status Examination for Organic Mental Syndrome in the Elderly Patient. In Geriatric Psychiatry. A Handbook for Psychiatrists and Primary Care Physicians; Bellak, L., Karasu, T., Eds.; Grune & Stratton: New York, NY, USA, 1976; pp. 77–121. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, K. A Normative Study of Neuropsychological Test Performance of a Normal Elderly Sample; University of Victoria: Victoria, BC, Canada, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R.; Friedl, W.; Fazekas, F.; Reinhart, B.; Grieshofer, P.; Koch, M.; Eber, B.; Schumacher, M.; Polmin, K.; Lechner, H. The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale: Normative data from 1001 healthy volunteers. Neurology 1994, 44, 964–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuffreda, K.; Kapoor, N.; Rutner, D.; Suchoff, I.; Han, M.; Craig, S. Occurrence of oculomotor dysfunctions in acquired brain in jury: A retrospective analysis. Optometry 2007, 78, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biessels, G.; Whitmer, R. Cognitive dysfunction in diabetes: How to implement emerging guidelines. Diabetologia 2020, 63, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, D.; King, A. Alcohol impairment of saccadic and smooth pursuit eye movements: Impact of risk factors for alcohol dependence. Psychopharmacology 2010, 212, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, P.; Modig, F.; Patel, M.; Gomez, S.; Magnusson, M. Oculomotor deficits caused by 0.06% and 0.10% blood alcohol concentrations and relationship to subjective perception of drunkenness. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2010, 121, 2134–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huestegge, L.; Kunert, H.; Radach, R. Long-term effects of cannabis on eye movement control in reading. Psychopharmacology 2010, 209, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploner, C.; Tschirch, A.; Ostendorf, F.; Dick, S.; Gaymard, B.; Rivaud-Pechoux, S.; Sporkert, F.; Pragst, F.; Stadelmann, A. Oculomotor effects of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in humans: Implications for the functional neuroanatomy of the brain cannabinoid system. Cereb. Cortex 2002, 12, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosnoski, E.; Yolton, R.; Citek, K.; Hates, C.; Evans, R. The Drug Evaluation Classification Program: Using ocular and other signs to detect drug intoxication. J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 1998, 69, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valliappan, N.; Dai, N.; Steinberg, E.; He, J.; Rogers, K.; Ramachandran, V.; Xu, P.; Shojaeizadeh, M.; Guo, L.; Kohlhoff, K.; et al. Accelerating eye movement research via accurate and affordable smartphone eye tracking. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.; Luke, S. Best practices in eye tracking research. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2020, 155, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall Population n = 206 | Cognitive Normal (CN) n = 166 | Possible MCI (PMCI) n = 40 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65.4 ± 9 | 64.9 ± 8.9 | 67.9 ± 9.1 |

| Sex | |||

| Female n (%) | 144 (70%) | 122 (73.5%) | 22 (55%) |

| Male n (%) | 62 (30%) | 44 (26.5%) | 18 (45%) |

| Education years | 16.2 ± 2.3 | 16.3 ± 2.3 | 16 ± 2.4 |

| DRS | 140.9 ± 3.1 | 142.1 ± 1.5 | 135.9 ± 3.2 |

| Time-Related Features | Eye Movement-Related Features |

|---|---|

| Fixations:

|

Saccades:

| |

Blinks:

| |

Pupillary Dynamics:

|

| Classification | Cognitive Normal (CN) Class | Possible MCI (PMCI) Class |

|---|---|---|

| Training dataset | 135 | 29 |

| Testing dataset | 31 | 11 |

| Classification | Cognitive Normal (CN) Class | Possible MCI (PMCI) Class |

|---|---|---|

| Training dataset | 135 | 135 |

| Testing dataset | 31 | 11 |

| Model | Hyper- Parameter | Recall/ Sensitivity | Precision | Specificity | F1-Score | Accuracy | AUPRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR–SMOTE | DT = 0.45 | 0.88 [0.73–0.9] | 0.87 [0.71–1] | 0.95 [0.87–1] | 0.87 [0.76–0.95] | 0.93 [0.88–0.98] | 0.94 [0.9–0.96] |

| DT = 0.5 | 0.87 [0.73–0.91] | 0.88 [0.75–1] | 0.96 [0.9–1] | 0.88 [0.76–0.95] | 0.94 [0.88–0.98] | ||

| LR–Original | DT = 0.45 | 0.73 [0.64–0.9] | 0.88 [0.7–1] | 0.89 [0.87–1] | 0.8 [0.7–0.9] | 0.9 [0.85–0.95] | 0.91 [0.84–0.96] |

| DT = 0.5 | 0.71 [0.64–0.9] | 0.91 [0.73–1] | 0.97 [0.9–1] | 0.79 [0.7–0.9] | 0.91 [0.86–0.95] | ||

| KNN–SMOTE | Best k = 6 | 0.85 [0.73–1] | 0.8 [0.66–1] | 0.92 [0.84–1] | 0.82 [0.73–0.92] | 0.9 [0.86–0.95] | 0.9 [0.82–0.98] |

| KNN–Original | Best k = 5 | 0.71 [0.54–0.9] | 0.96 [0.75–1] | 0.99 [0.9–1] | 0.81 [0.63–0.9] | 0.91 [0.83–0.95] | 0.9 [0.77–0.98] |

| Model | Hyper- Parameter | Recall/ Sensitivity | Precision | Specificity | F1-Score | Accuracy | AUPRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR–SMOTE | DT = 0.45 | 0.9 [0.81–0.91] | 0.77 [0.64–0.91] | 0.9 [0.84–0.97] | 0.83 [0.72–0.91] | 0.9 [0.83–0.95] | 0.93 [0.88–0.96] |

| DT = 0.5 | 0.89 [0.81–0.91] | 0.79 [0.67–0.91] | 0.94 [0.84–0.97] | 0.84 [0.86–0.95] | 0.91 [0.86–0.95] | ||

| LR–Original | DT = 0.45 | 0.8 [0.64–0.91] | 0.84 [0.73–1] | 0.94 [0.9–1] | 0.81 [0.7–0.91] | 0.9 [0.86–0.95] | 0.92 [0.86–0.96] |

| DT = 0.5 | 0.78 [0.64–0.91] | 0.85 [0.73–1] | 0.95 [0.9–1] | 0.81 [0.7–0.91] | 0.88 [0.86–0.95] | ||

| KNN–SMOTE | Best k = 6 | 0.87 [0.73–1] | 0.74 [0.64–0.9] | 0.89 [0.84–0.97] | 0.79 [0.7–0.9] | 0.88 [0.83–0.95] | 0.88 [0.79–0.97] |

| KNN–Original | Best k = 5 | 0.73 [0.54–0.91] | 0.97 [0.67–1] | 0.98 [0.87–1] | 0.83 [0.66–0.95] | 0.92 [0.83–0.98] | 0.91 [0.8–0.99] |

| Model | Hyper- Parameter | Recall/ Sensitivity | Precision | Specificity | F1-Score | Accuracy | AUPRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR–SMOTE | DT = 0.45 | 0.83 [0.82–0.91] | 0.9 [0.75–1] | 0.96 [0.9–1] | 0.86 [0.78–0.91] | 0.93 [0.88–0.95] | 0.96 [0.93–0.98] |

| DT = 0.5 | 0.82 [0.72–0.91] | 0.95 [0.81–1] | 0.98 [0.94–1] | 0.88 [0.82–0.9] | 0.94 [0.9–0.95] | ||

| LR–Original | DT = 0.45 | 0.73 [0.64–0.81] | 0.99 [0.89–1] | 0.99 [0.98–1] | 0.84 [0.78–0.9] | 0.93 [0.9–0.95] | 0.93 [0.89–0.98] |

| DT = 0.5 | 0.72 [0.64–0.81] | 0.99 [0.98–1] | 1 [0.98–1] | 0.84 [0.78–0.9] | 0.93 [0.9–0.95] | ||

| KNN–SMOTE | Best k = 6 | 0.81 [0.73–0.91] | 0.78 [0.61–0.91] | 0.91 [0.81–0.97] | 0.79 [0.69–0.91] | 0.89 [0.81–0.95] | 0.86 [0.76–0.94] |

| KNN–Original | Best k = 5 | 0.73 [0.54–0.81] | 0.89 [0.67–1] | 0.96 [0.87–1] | 0.8 [0.67–0.9] | 0.9 [0.83–0.95] | 0.88 [0.76–0.94] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pradhan, G.N.; Kingsbury, S.E.; Cevette, M.J.; Stepanek, J.; Caselli, R.J. AI-Driven Prediction of Possible Mild Cognitive Impairment Using the Oculo-Cognitive Addition Test (OCAT). Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010070

Pradhan GN, Kingsbury SE, Cevette MJ, Stepanek J, Caselli RJ. AI-Driven Prediction of Possible Mild Cognitive Impairment Using the Oculo-Cognitive Addition Test (OCAT). Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010070

Chicago/Turabian StylePradhan, Gaurav N., Sarah E. Kingsbury, Michael J. Cevette, Jan Stepanek, and Richard J. Caselli. 2026. "AI-Driven Prediction of Possible Mild Cognitive Impairment Using the Oculo-Cognitive Addition Test (OCAT)" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010070

APA StylePradhan, G. N., Kingsbury, S. E., Cevette, M. J., Stepanek, J., & Caselli, R. J. (2026). AI-Driven Prediction of Possible Mild Cognitive Impairment Using the Oculo-Cognitive Addition Test (OCAT). Brain Sciences, 16(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010070