Middle-Aged and Older Adults’ Beliefs, Ratings, and Preferences for Receiving Multicomponent Lifestyle-Based Brain Health Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

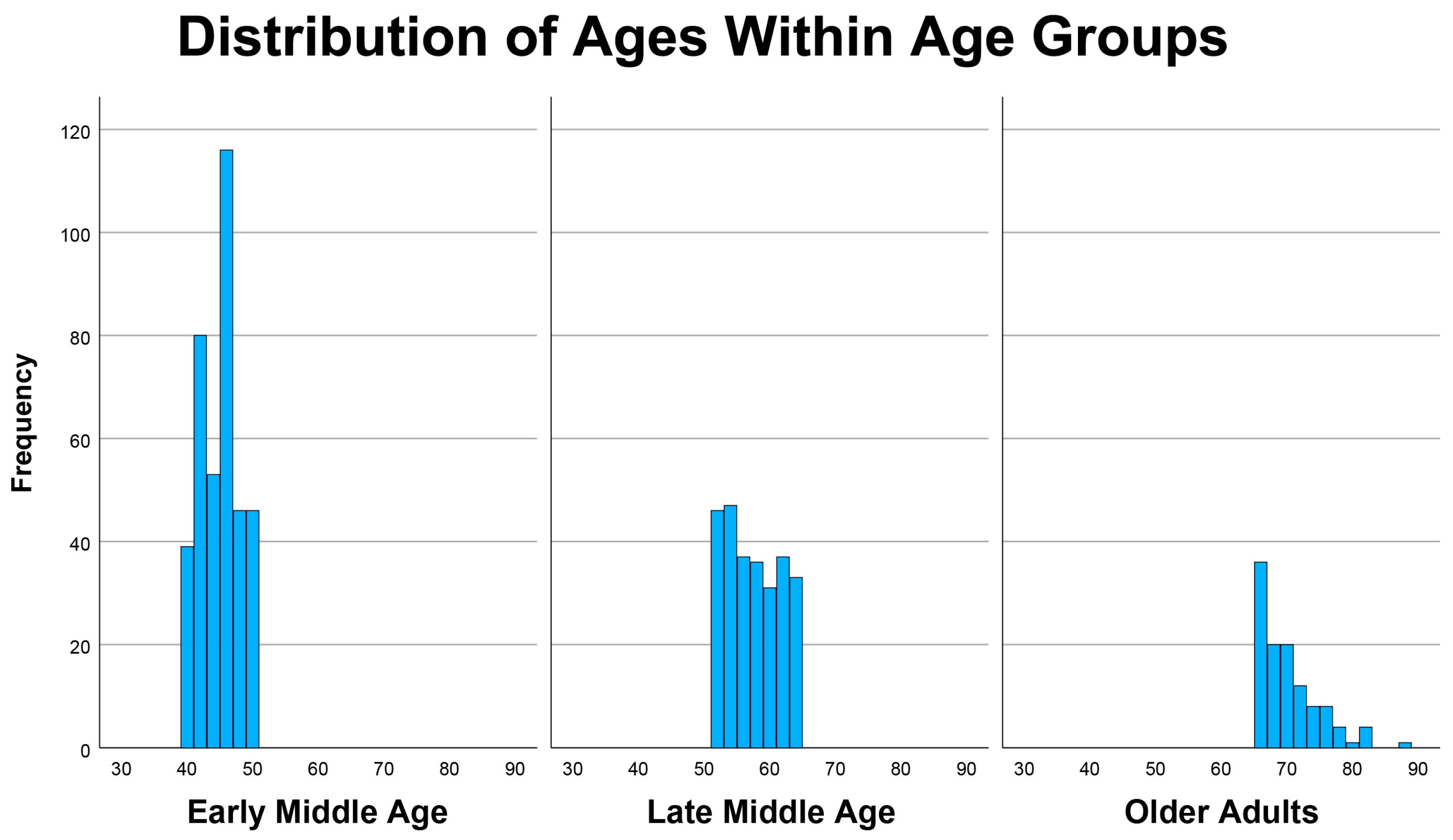

2.1. Human Subjects

2.2. Ratings of Activities

3. Results

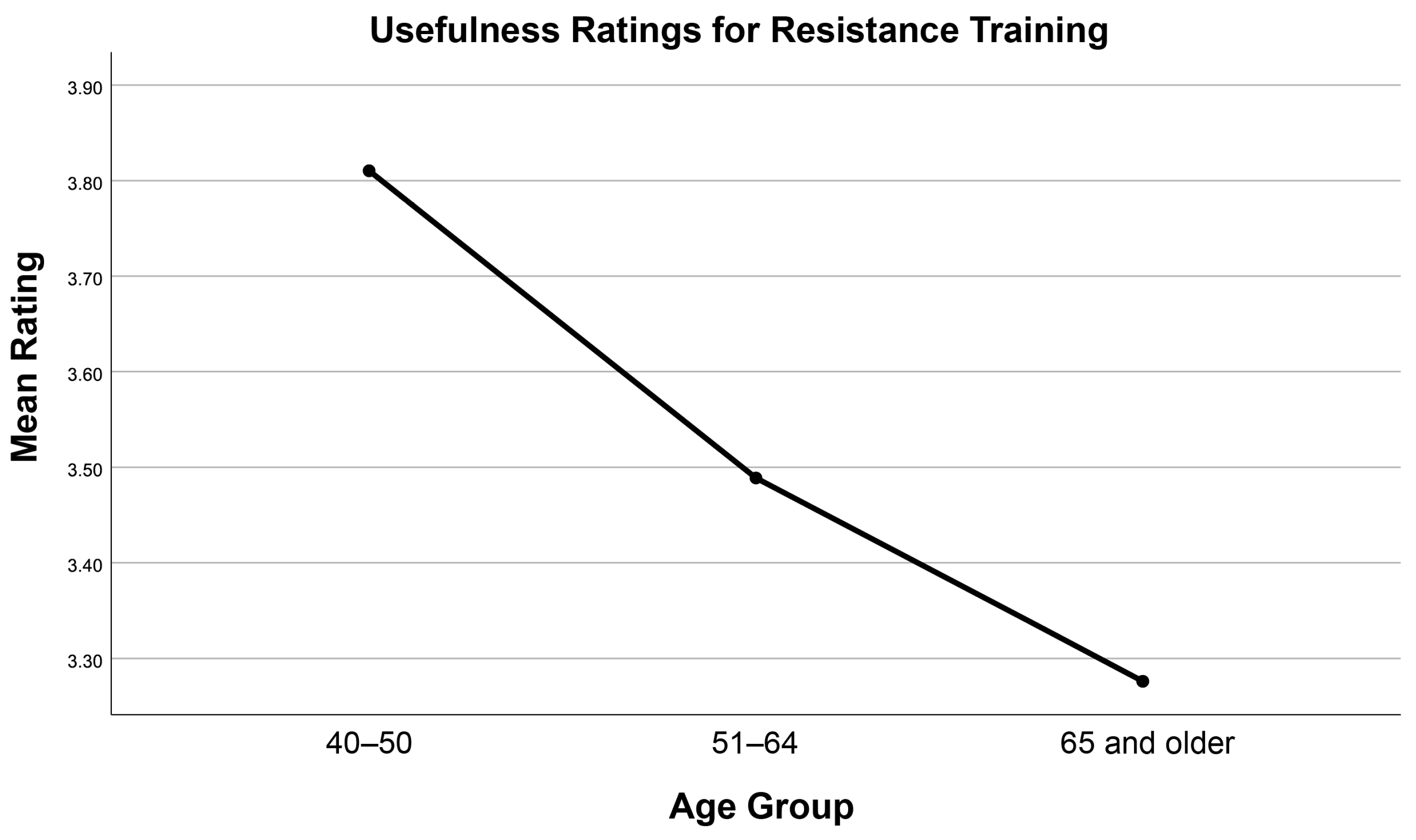

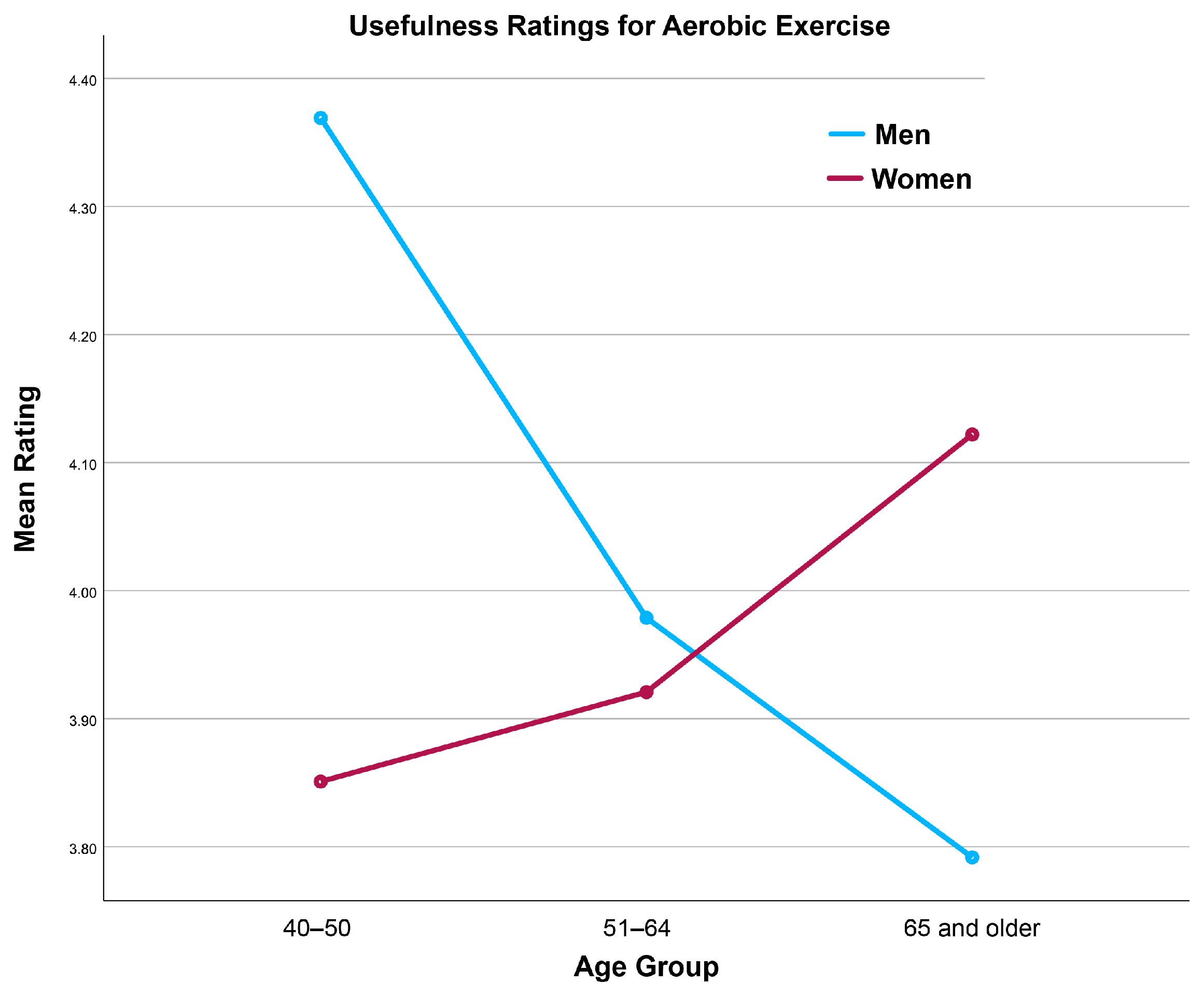

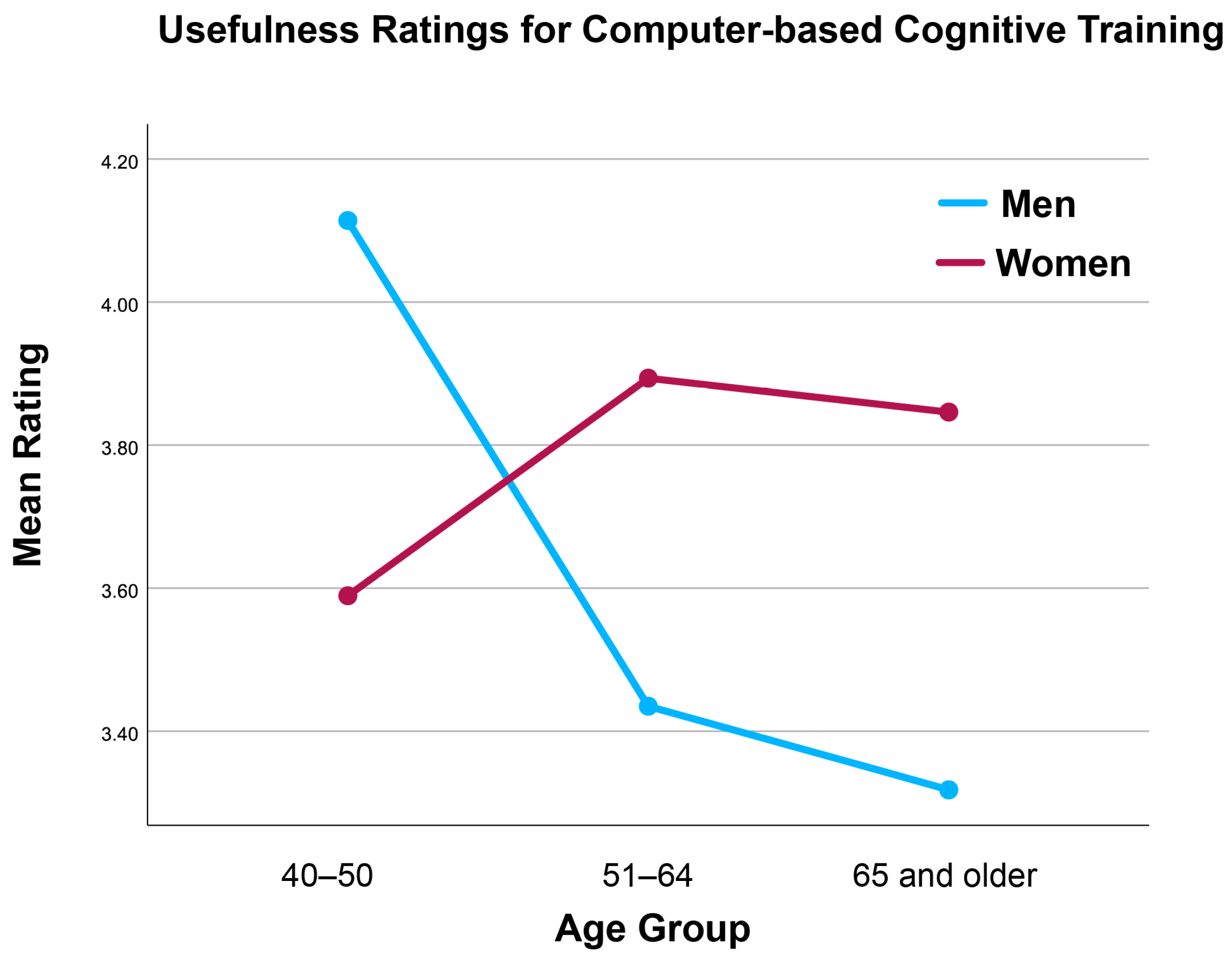

3.1. Ratings of Activities

3.2. Most Important Single Focus

3.3. Preferences for Service Delivery

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD. World Population Ageing 2020; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3898412/files/undesa_pd-2020_world_population_ageing_highlights.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- American Association of Retired Persons. Brain Healthy Behaviors and Worry About Cognitive Decline: Adults 40 and Older; American Association of Retired Persons: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ngandu, T.; Lehtisalo, J.; Solomon, A.; Levälahti, E.; Ahtiluoto, S.; Antikainen, R.; Bäckman, L.; Hänninen, T.; Jula, A.; Laatikainen, T.; et al. A 2-year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): A randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2015, 385, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.B.; Becofsky, K.; Anderson, L.A.; Bryant, L.L.; Hunter, R.H.; Ivey, S.L.; Belza, B.; Logsdon, R.G.; Brannon, S.; Vandenberg, A.E.; et al. Public perceptions about risk and protective factors for cognitive health and impairment: A review of the literature. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2015, 27, 1263–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niechcial, M.A.; Elhag, S.M.; Potter, L.M.; Dickson, A.; Gow, A.J. Systematic review of what people know about brain health. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 103, 102592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.A.; Day, K.L.; Beard, R.L.; Reed, P.S.; Wu, B. The public’s perceptions about cognitive health and Alzheimer’s disease among the U.S. Population: A national review. Gerontologist 2009, 49, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C.S.; Troutman-Jordan, M.; Nies, M.A. Brain health knowledge in community-dwelling older adults. Educ. Gerontol. 2012, 38, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zülke, A.; Luppa, M.; Köhler, S.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Knowledge of risk and protective factors for dementia in older German adults a population-based survey on risk and protective factors for dementia and internet-based brain health interventions. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, Y.; Rapsey, C.; Scott, K.M. Clusters of dementia literacy: Implications from a survey of older adults. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 9, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heger, I.; Deckers, K.; van Boxtel, M.; de Vugt, M.; Hajema, K.; Verhey, F.; Köhler, S. Dementia awareness and risk perception in middle-aged and older individuals: Baseline results of the MijnBreincoach survey on the association between lifestyle and brain health. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.B.; Laditka, J.N.; Hunter, R.; Ivey, S.L.; Wu, B.; Laditka, S.B.; Tseng, W.; Corwin, S.J.; Liu, R.; Mathews, A.E. Getting the message out about cognitive health: A cross-cultural comparison of older adults’ media awareness and communication needs on how to maintain a healthy brain. Gerontologist 2009, 49, S50–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman-Stein, P.E.; Luther, J.B.; Bierman, J.S.; Busko, S.E. Determining preferences and feasibility for instituting “brain healthy” lifestyle programs for older adults in a continuing care retirement community. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2007, 3, S126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownby, R.L.; Davenport, R. An online shared decision-making intervention for dementia prevention: A parallel-group randomized pilot study. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2023, 20, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia: WHO Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Preventing Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Way Forward; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, G.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Morris, T.P.; Sánchez, J.S.; Macià, D.; Tarrero, C.; Tormos, J.M.; Pascual-Leone, A. The Barcelona Brain Health Initiative: A cohort study to define and promote determinants of brain health. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, R.; Rountree, R. Science and music in support of SHIELDing the brain: A clinical conversation with Rudolph Tanzi, PhD, and Robert Rountree, MD. Altern. Complement. Ther. 2017, 23, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherzai, D.; Sherzai, A. The Alzheimer’s Solution; Simon & Schuster UK: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bredesen, D.E.; Amos, E.C.; Canick, J.; Ackerley, M.; Raji, C.; Fiala, M.; Ahdidan, J. Reversal of cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 2016, 8, 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- PASS 15 Power Analysis and Sample Size Software, version 15; NCSS: Kaysville, UT, USA, 2020.

- Bollen, K.; Lennox, R. Conventional wisdom on measurement: A structural equation perspective. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L. Being inconsistent about consistency: When coefficient alpha does and doesn’t matter. J. Pers. Assess. 2003, 80, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sireci, S.G. The construct of content validity. Soc. Indic. Res. 1998, 45, 83–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenze, E.J.; Voegtle, M.; Miller, J.P.; Ances, B.M.; Balota, D.A.; Barch, D.; Depp, C.A.; Diniz, B.S.; Eyler, L.T.; Foster, E.R.; et al. Effects of mindfulness training and exercise on cognitive function in older adults: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2022, 328, 2218–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Ambrose, T.; Nagamatsu, L.S.; Graf, P.; Beattie, B.L.; Ashe, M.C.; Handy, T.C. Resistance training and executive functions: A 12-month randomized controlled trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zainal, N.H.; Newman, M.G. AMindfulness enhances cognitive functioning: A meta-analysis of 111 randomized controlled trials. Health Psychol. Rev. 2024, 18, 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.; Berch, D.B.; Helmers, K.F.; Jobe, J.B.; Leveck, M.D.; Marsiske, M.; Morris, J.N.; Rebok, G.W.; Smith, D.M.; Tennstedt, S.L.; et al. Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002, 288, 2271–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, N.J.; Sachdev, P.S.; Fiatarone Singh, M.A.; Valenzuela, M. Cognitive and memory training in adults at risk of dementia: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2011, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artinian, N.T.; Fletcher, G.F.; Mozaffarian, D.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Van Horn, L.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Kumanyika, S.; Kraus, W.E.; Fleg, J.L.; Redeker, N.S.; et al. Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults. Circulation 2010, 122, 406–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, J.; Schatz, K.; Drexler, H. Gender influence on health and risk behavior in primary prevention: A systematic review. J. Public Health 2017, 25, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ownby, R.L. An online dementia prevention intervention using the Cogstim model: A pilot study. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 9, S110–S111. Available online: https://www.jpreventionalzheimer.com/all-issues.html?article=774 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Baker, L.D.; Beavers, D.P.; Cleveland, M.; Day, C.E.; Decarli, C.; Espeland, M.A.; Tomaszewski-Farias, S.E.; Jimenez-Maggiora, G.; Katula, J.; Kivipelto, M.; et al. U.S. POINTER: Study design and launch. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 15, P1262–P1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownby, R.L.; Caballero, J. Practical approaches to lifestyle interventions for enhancing brain health in older adults: A selective narrative review. Aging Health Res. 2025, 5, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownby, R.L.; Waldrop, D. Cogstim: A shared decision-making model to support older adults’ brain health. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2023, 20, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic exercise | 733 | 3.94 | 1.07 |

| Strength or resistance training | 681 | 3.55 | 1.20 |

| Mentally stimulating activities | 750 | 4.23 | 0.95 |

| Using a computer several times a week | 732 | 3.72 | 1.15 |

| Learning a language or musical instrument | 651 | 3.81 | 1.15 |

| Following a diet rich in fruits and vegetables | 723 | 4.03 | 1.04 |

| Computer-based cognitive training | 655 | 3.71 | 1.13 |

| Getting together once a month or more often with friends or family | 731 | 3.94 | 1.09 |

| Creative activities like painting, music, or writing | 719 | 4.12 | 0.97 |

| Meditating | 691 | 3.72 | 1.13 |

| Getting regular sleep | 742 | 4.27 | 0.98 |

| Reducing alcohol use | 683 | 4.03 | 1.14 |

| Stopping or never smoking | 665 | 4.15 | 1.17 |

| Managing stress | 733 | 4.26 | 0.92 |

| Regular medical checkups | 739 | 4.09 | 1.05 |

| Maintaining a healthy weight | 727 | 3.95 | 1.06 |

| Coping with depression or not being depressed | 711 | 4.07 | 1.08 |

| Getting a hearing test or using a hearing aid if you have trouble hearing | 622 | 3.86 | 1.19 |

| Taking brain health supplements | 651 | 3.64 | 1.23 |

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic exercise | 9.78 | 2 | 4.89 | 4.94 | 0.008 |

| Strength or resistance training | 18.02 | 2 | 9.01 | 6.96 | 0.001 |

| Mentally stimulating activities | 3.14 | 2 | 1.57 | 1.85 | 0.158 |

| Using a computer several times a week | 18.00 | 2 | 9.00 | 7.19 | 0.001 |

| Learning a language or musical instrument | 6.01 | 2 | 3.00 | 2.43 | 0.089 |

| Following a diet rich in fruits and vegetables | 5.19 | 2 | 2.59 | 2.70 | 0.069 |

| Computer-based cognitive training | 26.72 | 2 | 13.36 | 10.99 | <0.001 |

| Getting together once a month or more often with friends or family | 26.16 | 2 | 13.08 | 12.43 | <0.001 |

| Creative activities like painting, music, or writing | 13.15 | 2 | 6.57 | 7.97 | <0.001 |

| Meditating | 25.35 | 2 | 12.68 | 11.36 | <0.001 |

| Getting regular sleep | 6.05 | 2 | 3.03 | 3.44 | 0.033 |

| Reducing alcohol use | 12.82 | 2 | 6.41 | 5.94 | 0.003 |

| Stopping or never smoking | 2.97 | 2 | 1.48 | 1.17 | 0.313 |

| Managing stress | 4.53 | 2 | 2.27 | 2.96 | 0.053 |

| Regular medical checkups | 12.34 | 2 | 6.17 | 6.15 | 0.002 |

| Maintaining a healthy weight | 16.27 | 2 | 8.14 | 7.81 | <0.001 |

| Coping with depression or not being depressed | 16.88 | 2 | 8.44 | 7.98 | <0.001 |

| Getting a hearing test or using a hearing aid if you have trouble hearing | 20.33 | 2 | 10.16 | 8.05 | <0.001 |

| Taking brain health supplements | 34.27 | 2 | 17.13 | 13.81 | <0.001 |

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Work with a provider who can give me a test | 393 | 51.6 |

| Online educational workshops or classes | 335 | 44.0 |

| App on my phone to test my memory and thinking | 277 | 36.4 |

| Work with a provider to develop a brain health plan | 226 | 29.7 |

| In person educational workshops or classes | 224 | 29.4 |

| App on my phone to track brain health activities | 207 | 27.2 |

| Reading a regular newsletter | 170 | 22.3 |

| Podcasts or video online | 157 | 20.6 |

| Working in a group face to face | 136 | 17.9 |

| Being able to text someone to get a quick answer | 128 | 16.9 |

| Online message board | 88 | 11.6 |

| E-mail consults with providers | 81 | 10.6 |

| Working in a group online | 60 | 10.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ownby, R.L.; Cavanaugh, G.; Weatherly, S.; Akhtarullah, S.; Caballero, J. Middle-Aged and Older Adults’ Beliefs, Ratings, and Preferences for Receiving Multicomponent Lifestyle-Based Brain Health Interventions. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010069

Ownby RL, Cavanaugh G, Weatherly S, Akhtarullah S, Caballero J. Middle-Aged and Older Adults’ Beliefs, Ratings, and Preferences for Receiving Multicomponent Lifestyle-Based Brain Health Interventions. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleOwnby, Raymond L., Gesulla Cavanaugh, Shannon Weatherly, Shazia Akhtarullah, and Joshua Caballero. 2026. "Middle-Aged and Older Adults’ Beliefs, Ratings, and Preferences for Receiving Multicomponent Lifestyle-Based Brain Health Interventions" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010069

APA StyleOwnby, R. L., Cavanaugh, G., Weatherly, S., Akhtarullah, S., & Caballero, J. (2026). Middle-Aged and Older Adults’ Beliefs, Ratings, and Preferences for Receiving Multicomponent Lifestyle-Based Brain Health Interventions. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010069