Imaging Scores in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Performance on Prediction of Functional Outcome, Mortality, and Complications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

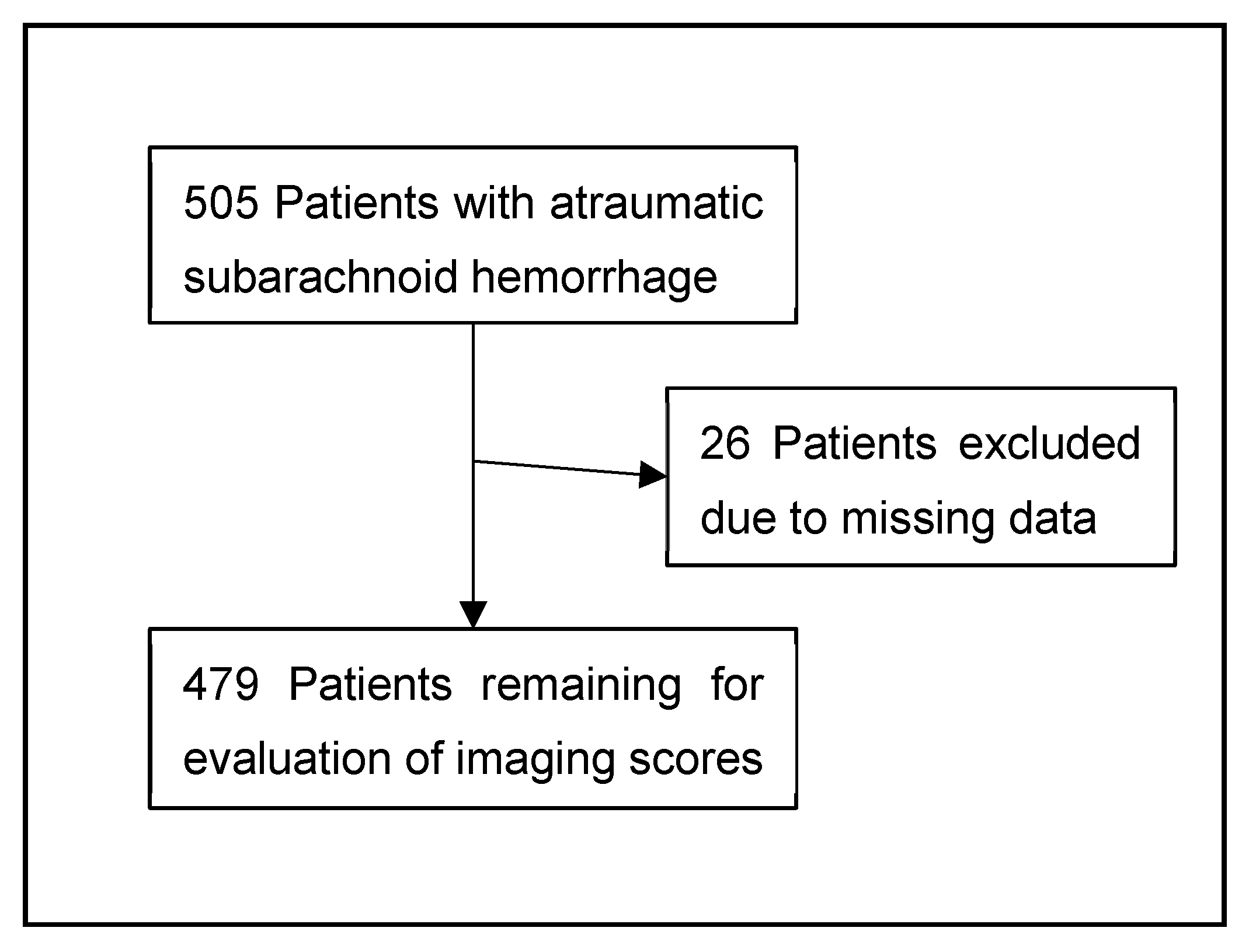

2.1. Patient Identification and Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Clinical Parameters

2.3. Imaging

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Imaging Assessment on Admission

3.2. Outcomes

3.3. ROC Analyses of Initial Imaging with the Primary Endpoint

3.4. ROC Analyses of Secondary Endpoints

3.5. Multivariable Analysis

3.6. Subgroup Analyses Regarding the Primary Endpoint

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DCI | Delayed cerebral ischemia |

| SAH | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| ICH | Intracerebral hemorrhage |

| HH | Hunt and Hess |

| WFNS | World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies |

| IVH | Intraventricular hemorrhage |

| mRS | Modified Rankin scale |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| aOR | Adjusted odds ratio |

References

- van Gijn, J.; Kerr, R.S.; Rinkel, G.J. Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. Lancet 2007, 369, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, J.P.; Dulhanty, L.; Patel, H.C. Predictors of Outcome in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Patients: Observations from a Multicenter Data Set. Stroke 2017, 48, 2958–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerner, S.T.; Reichl, J.; Custal, C.; Brandner, S.; Eyüpoglu, I.Y.; Lücking, H.; Hölter, P.; Kallmünzer, B.; Huttner, H.B. Long-Term Complications and Influence on Outcome in Patients Surviving Spontaneous Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 49, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, G.M.; Drake, C.G.; Hunt, W.; Kassell, N.; Sano, K.; Pertuiset, B.; De Villiers, J.C. A Universal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Scale: Report of a Committee of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1988, 51, 1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasdale, G.; Maas, A.; Lecky, F.; Manley, G.; Stocchetti, N.; Murray, G. The Glasgow Coma Scale at 40 Years: Standing the Test of Time. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, W.E.; Hess, R.M. Surgical Risk as Related to Time of Intervention in the Repair of Intracranial Aneurysms. J. Neurosurg. 1968, 28, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, E.S., Jr.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Carhuapoma, J.R.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Dion, J.; Higashida, R.T.; Hoh, B.L.; Kirkness, C.J.; Naidech, A.M.; Ogilvy, C.S.; et al. Guidelines for the Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2012, 43, 1711–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, J.A.; Claassen, J.; Schmidt, J.M.; Wartenberg, K.E.; Temes, R.; Connolly, E.S., Jr.; MacDonald, R.L.; Mayer, S.A. Prediction of Symptomatic Vasospasm after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: The Modified Fisher Scale. Neurosurgery 2006, 59, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, J.; Bernardini, G.L.; Kreiter, K.; Bates, J.; Du, Y.E.; Copeland, D.; Connolly, E.S.; Mayer, S.A. Effect of Cisternal and Ventricular Blood on Risk of Delayed Cerebral Ischemia after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: The Fisher Scale Revisited. Stroke 2001, 32, 2012–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijdra, A.; Brouwers, P.J.; Vermeulen, M.; van Gijn, J. Grading the Amount of Blood on Computed Tomograms after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Stroke 1990, 21, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeb, D.A.; Robertson, W.D.; Lapointe, J.S.; Nugent, R.A.; Harrison, P.B. Computed Tomographic Diagnosis of Intraventricular Hemorrhage. Etiology and Prognosis. Radiology 1982, 143, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallevi, H.; Dar, N.S.; Barreto, A.D.; Morales, M.M.; Martin-Schild, S.; Abraham, A.T.; Walker, K.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; Illoh, K.; Grotta, J.C.; et al. The Ivh Score: A Novel Tool for Estimating Intraventricular Hemorrhage Volume: Clinical and Research Implications. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 969-e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frontera, J.A.; Fernandez, A.; Schmidt, J.M.; Claassen, J.; Wartenberg, K.E.; Badjatia, N.; Connolly, E.S.; Mayer, S.A. Defining Vasospasm after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: What Is the Most Clinically Relevant Definition? Stroke 2009, 40, 1963–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golicki, D.; Niewada, M.; Buczek, J.; Karlińska, A.; Kobayashi, A.; Janssen, M.F.; Pickard, A.S. Validity of Eq-5d-5l in Stroke. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Rakesh, D.; Ramnadha, R.; Manas, P. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Hydrocephalus. Neurol. India 2021, 69, S429–S433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, J.V.; Pan, J.; Rai, S.N.; Galandiuk, S. Roc-Ing Along: Evaluation and Interpretation of Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves. Surgery 2016, 159, 1638–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, J.C., 3rd; Bonovich, D.C.; Besmertis, L.; Manley, G.T.; Johnston, S.C. The Ich Score: A Simple, Reliable Grading Scale for Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke 2001, 32, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Perry, J.J.; English, S.W.; Alkherayf, F.; Joseph, J.; Nobile, S.; Zhou, L.L.; Lesiuk, H.; Moulton, R.; Agbi, C.; et al. Clinical Prediction of Delayed Cerebral Ischemia in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 130, 1914–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Steen, W.E.; Leemans, E.L.; van den Berg, R.; Roos, Y.; Marquering, H.A.; Verbaan, D.; Majoie, C. Radiological Scales Predicting Delayed Cerebral Ischemia in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuroradiology 2019, 61, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.H.; Hehir, M.; Nathan, B.; Gress, D.; Dumont, A.S.; Kassell, N.F.; Bleck, T.P. A Comparison of 3 Radiographic Scales for the Prediction of Delayed Ischemia and Prognosis Following Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 2008, 109, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Roldán, L.; Alén, J.F.; Gómez, P.A.; Lobato, R.D.; Ramos, A.; Munarriz, P.M.; Lagares, A. Volumetric Analysis of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Assessment of the Reliability of Two Computerized Methods and Their Comparison with Other Radiographic Scales. J. Neurosurg. 2013, 118, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greebe, P.; Rinkel, G.J.; Hop, J.W.; Visser-Meily, J.M.; Algra, A. Functional Outcome and Quality of Life 5 and 12.5 Years after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 2059–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kelly, C.J.; Kulkarni, A.V.; Austin, P.C.; Urbach, D.; Wallace, M.C. Shunt-Dependent Hydrocephalus after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Incidence, Predictors, and Revision Rates. Clinical Article. J. Neurosurg. 2009, 111, 1029–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasenbrock, H.H.; Angriman, F.; Smith, T.R.; Gormley, W.B.; Frerichs, K.U.; Aziz-Sultan, M.A.; Du, R. Readmission after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Nationwide Readmission Database Analysis. Stroke 2017, 48, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Russo, P.; Di Carlo, D.T.; Lutenberg, A.; Morganti, R.; Evins, A.I.; Perrini, P. Shunt-Dependent Hydrocephalus after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. Sci. 2020, 64, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claassen, J.; Peery, S.; Kreiter, K.T.; Hirsch, L.J.; Du, E.Y.; Connolly, E.S.; Mayer, S.A. Predictors and Clinical Impact of Epilepsy after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurology 2003, 60, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, J.; Kurki, M.I.; von Und Zu Fraunberg, M.; Koivisto, T.; Ronkainen, A.; Rinne, J.; Jääskeläinen, J.E.; Kälviäinen, R.; Immonen, A. Epilepsy after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Population-Based, Long-Term Follow-up Study. Neurology 2015, 84, 2229–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custal, C.; Koehn, J.; Borutta, M.; Mrochen, A.; Brandner, S.; Eyüpoglu, I.Y.; Lücking, H.; Hoelter, P.; Kuramatsu, J.B.; Kornhuber, J.; et al. Beyond Functional Impairment: Redefining Favorable Outcome in Patients with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 50, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Manoel, A.L.; Mansur, A.; Silva, G.S.; Germans, M.R.; Jaja, B.N.; Kouzmina, E.; Marotta, T.R.; Abrahamson, S.; Schweizer, T.A.; Spears, J.; et al. Functional Outcome after Poor-Grade Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Single-Center Study and Systematic Literature Review. Neurocrit. Care 2016, 25, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, M.E.; Tso, M.K.; Ayling, O.G.S.; Wong, J.H.; MacDonald, R.L. Unfavorable Outcome after Good Grade Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Exploratory Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2020, 144, e842–e848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergouwen, M.D.; Jong-Tjien-Fa, A.V.; Algra, A.; Rinkel, G.J. Time Trends in Causes of Death after Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Hospital-Based Study. Neurology 2016, 86, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Manoel, A.L.; Jaja, B.N.; Germans, M.R.; Yan, H.; Qian, W.; Kouzmina, E.; Marotta, T.R.; Turkel-Parrella, D.; Schweizer, T.A.; Macdonald, R.L. The Vasograde: A Simple Grading Scale for Prediction of Delayed Cerebral Ischemia after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Stroke 2015, 46, 1826–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, V.H.; Ouyang, B.; John, S.; Conners, J.J.; Garg, R.; Bleck, T.P.; Temes, R.E.; Cutting, S.; Prabhakaran, S. Risk Stratification for the in-Hospital Mortality in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: The Hair Score. Neurocrit. Care 2014, 21, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, I.S.; Chun, H.J.; Choi, K.S.; Yi, H.J. Modified Glasgow Coma Scale for Predicting Outcome after Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Surgery. Medicine 2021, 100, e25815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.; Juvela, S.; Unterberg, A.; Jung, C.; Forsting, M.; Rinkel, G. European Stroke Organization Guidelines for the Management of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Haemorrhage. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013, 35, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SAH-Scores | IVH Scores | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Fisher Scale | Claassen Score | Hijdra Score | Graeb Score | IVH Score | |

| Publication date | 2001 | 2001 | 1990 | 1982 | 2009 |

| Range | 0–4 | 1–5 | 0–42 | 0–12 | 0–23 |

| Score definition/calculation | 0: No SAH or IVH 1: Thin SAH, no IVH in both lateral ventricles 2: Thin SAH, with IVH in both lateral ventricles 3: Thick SAH, no IVH in both lateral ventricles 4: Thick SAH, with IVH in both lateral ventricles | 1: No SAH or IVH 2: Thin SAH, no IVH in both lateral ventricles 3: Thin SAH, with IVH in both lateral ventricles 4: Thick SAH, no IVH in both lateral ventricles 5: Thick SAH, with IVH in both lateral ventricles | 10 basal cisterns (0–3): 0: no blood 1: small amount of blood 2: moderately filled with blood 3: completely filled with blood Each ventricle (0–3): 0: no blood 1: sedimentation of blood 2: partly filled with blood 3: completely filled with blood | Each lateral ventricles: 1: trace of blood or mild bleeding 2: less than half of the ventricle filled with blood 3: more than half of the ventricle filled with blood 4: ventricle filled with blood and expanded Third and fourth ventricles: 0: no blood 1: blood present, ventricle size normal 2: ventricle filled with blood and expanded | IVHS = 3x (RV + LV) + III + IV+ 3x H Grade each lateral ventricle (RV/LV): 0: no blood or small amount 1: up to one-third filled with blood 2: one-to-two-thirds filled with blood 3: mostly or completely filled with blood Third and fourth ventricle (III/IV): 0: no blood 1: partially or completely filled with blood Hydrocephalus (H) present (1) or absent (0). |

| Validated for: | |||||

| Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| SAH Patients (n = 479) | |

|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 56.1 (±13.6) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 307 (64.1) |

| Prior comorbidities: | |

| Premorbid mRS, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 267 (55.7) |

| Nicotine abuse, n (%) | 137 (28.6) |

| Prior SAH, n (%) | 5 (1.0) |

| Admission status: | |

| GCS, median (IQR) | 14 (11–15) |

| Hunt and Hess, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) |

| WFNS, median (IQR) | 2 (2–4) |

| Poor-grade SAH (WFNS ≥ 4), n (%) | 179/477 (37.5) |

| SAH characteristics: | |

| Aneurysmal SAH, n (%) | 361/466 (75.4%) |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage, n (%) | 287/479 (59.9%) |

| Imaging scores: | |

| mFisher score, median (IQR) | 2 (1–3) |

| 0, n (%) | 23 (4.8) |

| 1 or 2, n (%) | 251 (52.4) |

| 3 or 4, n (%) | 205 (42.7) |

| Claassen score, median (IQR) | 3 (2–4) |

| 1, n (%) | 24 (5) |

| 2 or 3, n (%) | 257 (53.7) |

| 4 or 5, n (%) | 197 (41.2) |

| Hijdra score, median (IQR) | 8 (4–8) |

| 0–10, n (%) | 322 (67.2) |

| 11–20, n (%) | 150 (31.3) |

| 21–30, n (%) | 7 (1.4) |

| Graeb score, median (IQR) | 1 (1–3) |

| 0–4, n (%) | 423 (88.3) |

| 5–8, n (%) | 39 (8.1) |

| 9–12, n (%) | 17 (3.5) |

| IVH Score, median (IQR) | 4 (4–9) |

| 0–7, n (%) | 326 (68.0) |

| 8–15, n (%) | 125 (26.0) |

| 16–23, n (%) | 28 (5.8) |

| Outcome: | |

| Doppler sonographic vasospasm n (%) | 182/402 (45.3) |

| DCI, n (%) | 134/472 (28.4) |

| CSF shunt, n (%) | 99 (20.7) |

| Epilepsy, n (%) | 34/334 (10.2) |

| Mortality at discharge | 69 (14.4) |

| Mortality at 12-month, n (%) | 94 (19.6) |

| mRS at discharge, median (IQR) | 3 (2–5) |

| Favorable 0–3, n (%) | 248 (51.8) |

| Unfavorable 4–6, n (%) | 231 (48.2) |

| mRS at 3 months, median (IQR) | 2 (1–5) |

| Favorable 0–3, n (%) | 275/415 (66.3) |

| Unfavorable 4–6, n (%) | 140/415 (33.7) |

| mRS at 12 months, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) |

| Favorable 0–3, n (%) | 313/435 (72.0) |

| Unfavorable 4–6, n (%) | 122/435 (28.0) |

| Return to work, n (%) | 137/236 (58.1%) |

| EQ-VAS index, median (IQR) | 75 (55–90) |

| Unfavorable 0–74, n (%) | 154/333 (46.2) |

| Favorable 75–100, n (%) | 179/333 (53.8) |

| EQ-5D domains: | |

| Mobility = 0, n (%) | 66/332 (19.9) |

| Self-care = 0, n (%) | 60/332 (18.1) |

| Usual activities = 0, n (%) | 115/332 (34.6) |

| Pain/discomfort = 0, n (%) | 122/331 (36.9) |

| Anxiety/depression = 0, n (%) | 158/330 (47.9) |

| Imaging Score | mRS 4–6 (12 m) | Mortality (12 m) | CSF Shunt | EQ-5D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUROC (95% CI) | Adj. OR (95% CI) | AUROC (95% CI) | Adj. OR (95% CI) | AUROC (95% CI) | Adj. OR (95% CI) | AUROC (95% CI) | Adj. OR (95% CI) | |

| Modified Fisher | 0.713 (0.662–0.764) | 1.060 (1.022–1.101) | 0.713 (0.654–0.772) | 1.042 (1.009–1.076) | 0.721 (0.661–0.780) | 1.053 (1.018–1.089) | 0.410 (0.349–0.471) | 0.968 (0.923–1.016) |

| Claassen | 0.724 (0.675–0.774) | 1.070 (1.030–1.110) | 0.721 (0.662–0.779) | 1.045 (1.011–1.080) | 0.736 (0.679–0.793) | 1.058 (1.022–1.095) | 0.402 (0.341–0.463) | 0.961 (0.915–1.009) |

| Hijdra | 0.688 (0.635–0.740) | 1.009 (1.001–1.018) | 0.702 (0.641–0.764) | 1.009 (1.001–1.017) | 0.740 (0.683–0.796) | 1.010 (1.002–1.018) | 0.422 (0.361–0.484) | 0.995 (0.983–1.008) |

| Graeb | 0.732 (0.682–0.782) | 1.046 (1.028–1.065) | 0.735 (0.675–0.794) | 1.036 (1.016–1.056) | 0.761 (0.703–0.819) | 1.020 (1.001–1.041) | 0.407 (0.346–0.468) | 0.967 (0.944–0.991) |

| IVH Score | 0.721 (0.671–0.771) | 1.018 (1.010–1.026) | 0.711 (0.651–0.771) | 1.013 (1.004–1.021) | 0.771 (0.716–0.826) | 1.011 (1.003–1.020) | 0.402 (0.341–0.464) | 0.985 (0.974–0.996) |

| Imaging Score | Epilepsy | Return to work | Rebleeding | DCI | ||||

| AUROC (95% CI) | Adj. OR (95% CI) | AUROC (95% CI) | Adj. OR (95% CI) | AUROC (95% CI) | Adj. OR (95% CI) | AUROC (95% CI) | Adj. OR (95% CI) | |

| Modified Fisher | 0.592 (0.487–0.698) | 1.007 (0.974–1.042) | 0.302 (0.245–0.359) | 0.965 (0.916–1.016) | 0.580 (0.485–0.676) | 1.016 (0.990–1.044) | 0.643 (0.588–0.698) | 1.084 (1.043–1.126) |

| Claassen | 0.601 (0.497–0.706) | 1.010 (0.976–1.045) | 0.289 (0.234–0.345) | 0.955 (0.907–1.005) | 0.584 (0.489–0.680) | 1.018 (0.990–1.046) | 0.651 (0.596–0.705) | 1.090 (1.049–1.132) |

| Hijdra | 0.621 (0.525–0.717) | 1.001 (0.994–1.008) | 0.311 (0.254–0.368) | 0.986 (0.974–0.998) | 0.644 (0.551–0.738) | 1.007 (1.001–1.013) | 0.634 (0.580–0.688) | 1.014 (1.004–1.023) |

| Graeb | 0.632 (0.528–0.735) | 1.020 (0.996–1.044) | 0.292 (0.237–0.348) | 0.984 (0.954–1.014) | 0.537 (0.451–0.622) | 0.996 (0.985–1.007) | 0.601 (0.545–0.656) | 1.020 (1.000–1.041) |

| IVH Score | 0.623 (0.519–0.727) | 1.006 (0.997–1.015) | 0.312 (0.255–0.369) | 0.995 (0.982–1.009) | 0.519 (0.429–0.609) | 0.998 (0.993–1.004) | 0.604 (0.550–0.658) | 1.009 (1.000–1.017) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Biburger, L.; Mers, L.; Bogdanova, A.; Sekita, A.; Borutta, M.; Delev, D.; Bozhkov, Y.; Schnell, O.; Engelhorn, T.; Singer, L.; et al. Imaging Scores in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Performance on Prediction of Functional Outcome, Mortality, and Complications. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010028

Biburger L, Mers L, Bogdanova A, Sekita A, Borutta M, Delev D, Bozhkov Y, Schnell O, Engelhorn T, Singer L, et al. Imaging Scores in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Performance on Prediction of Functional Outcome, Mortality, and Complications. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleBiburger, Luise, Lena Mers, Anna Bogdanova, Alexander Sekita, Matthias Borutta, Daniel Delev, Yavor Bozhkov, Oliver Schnell, Tobias Engelhorn, Ludwig Singer, and et al. 2026. "Imaging Scores in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Performance on Prediction of Functional Outcome, Mortality, and Complications" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010028

APA StyleBiburger, L., Mers, L., Bogdanova, A., Sekita, A., Borutta, M., Delev, D., Bozhkov, Y., Schnell, O., Engelhorn, T., Singer, L., Sprügel, M., Schwab, S., & Gerner, S. T. (2026). Imaging Scores in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Performance on Prediction of Functional Outcome, Mortality, and Complications. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010028