Improving Lexicosemantic Impairments in Post-Stroke Aphasia Using rTMS Targeting the Right Anterior Temporal Lobe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

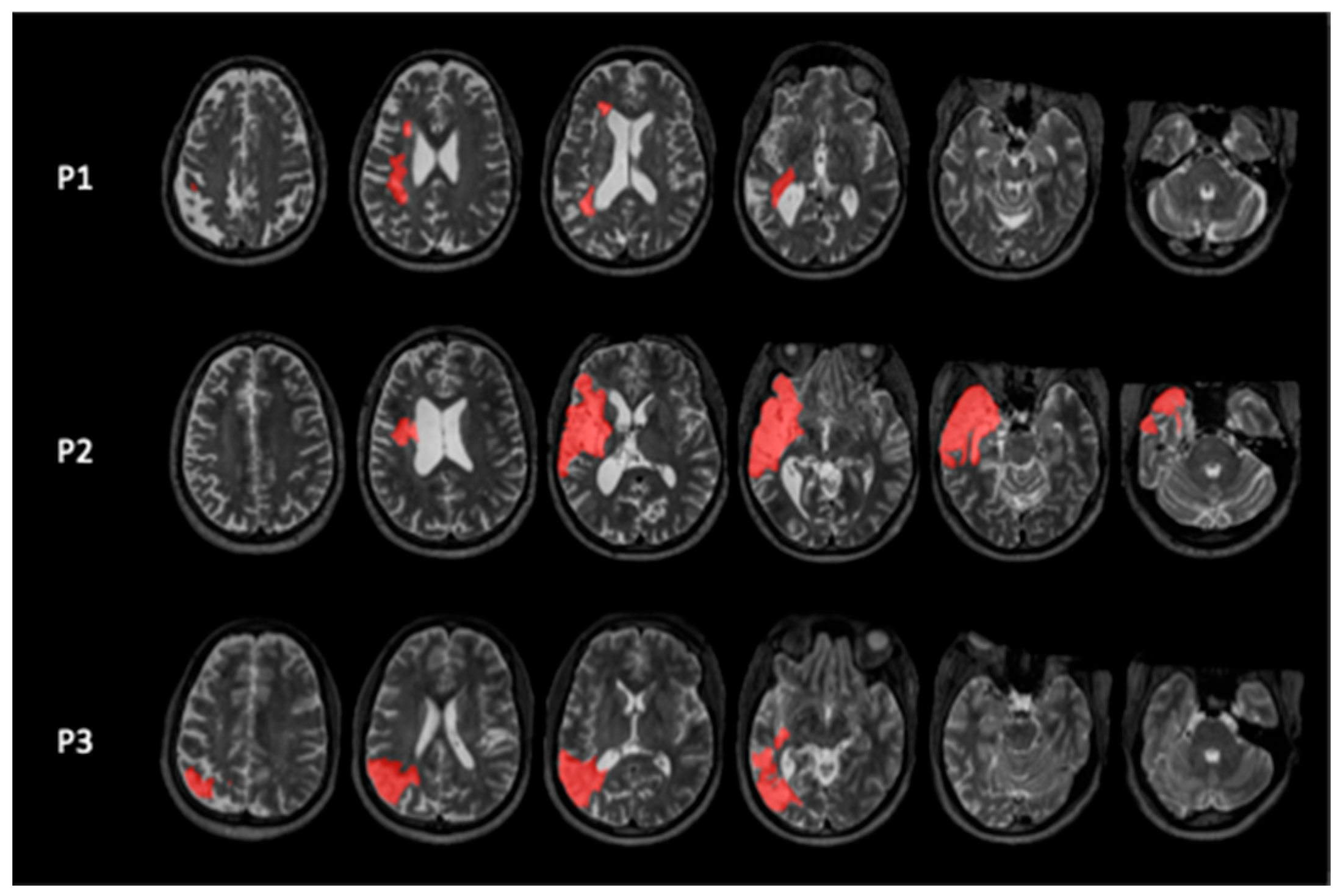

2.1. Participants

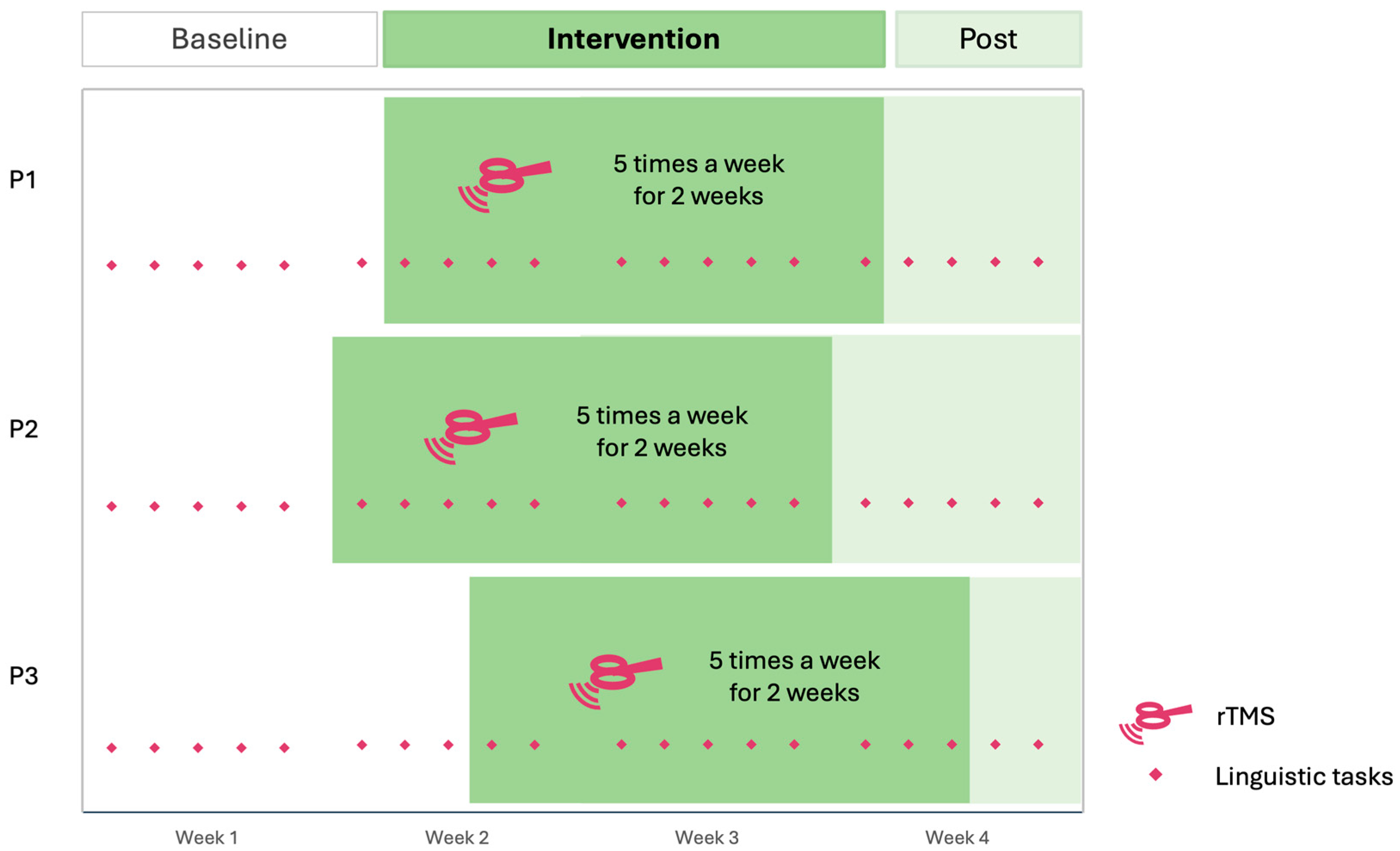

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Behavioral Measures

2.3.1. Naming Tasks

2.3.2. Semantic Decision Task

2.3.3. Peer Conflict Resolution

2.3.4. SAQOL-39

2.4. rTMS

2.5. Analysis

2.5.1. Data Analysis and Cleaning

2.5.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Naming Tasks

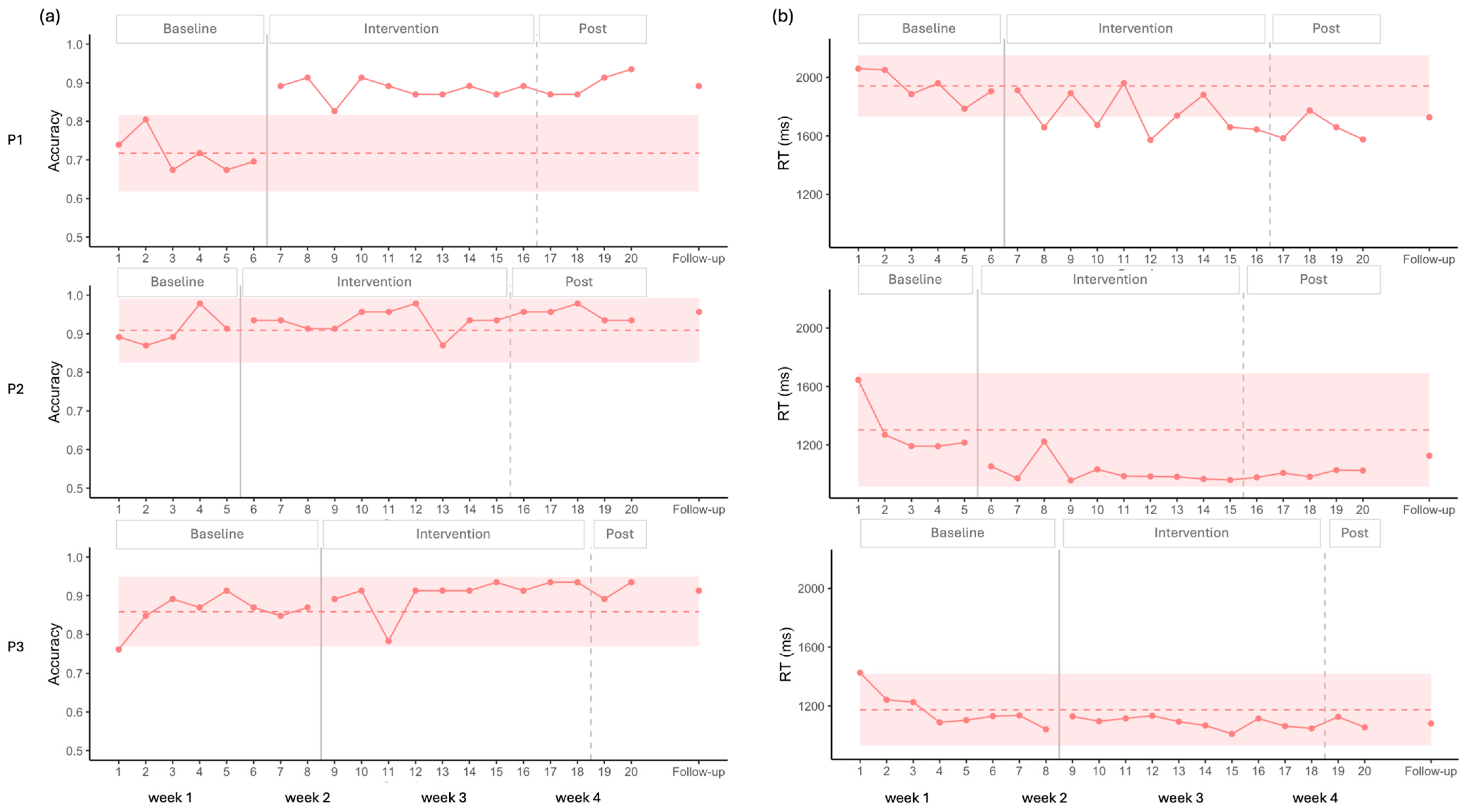

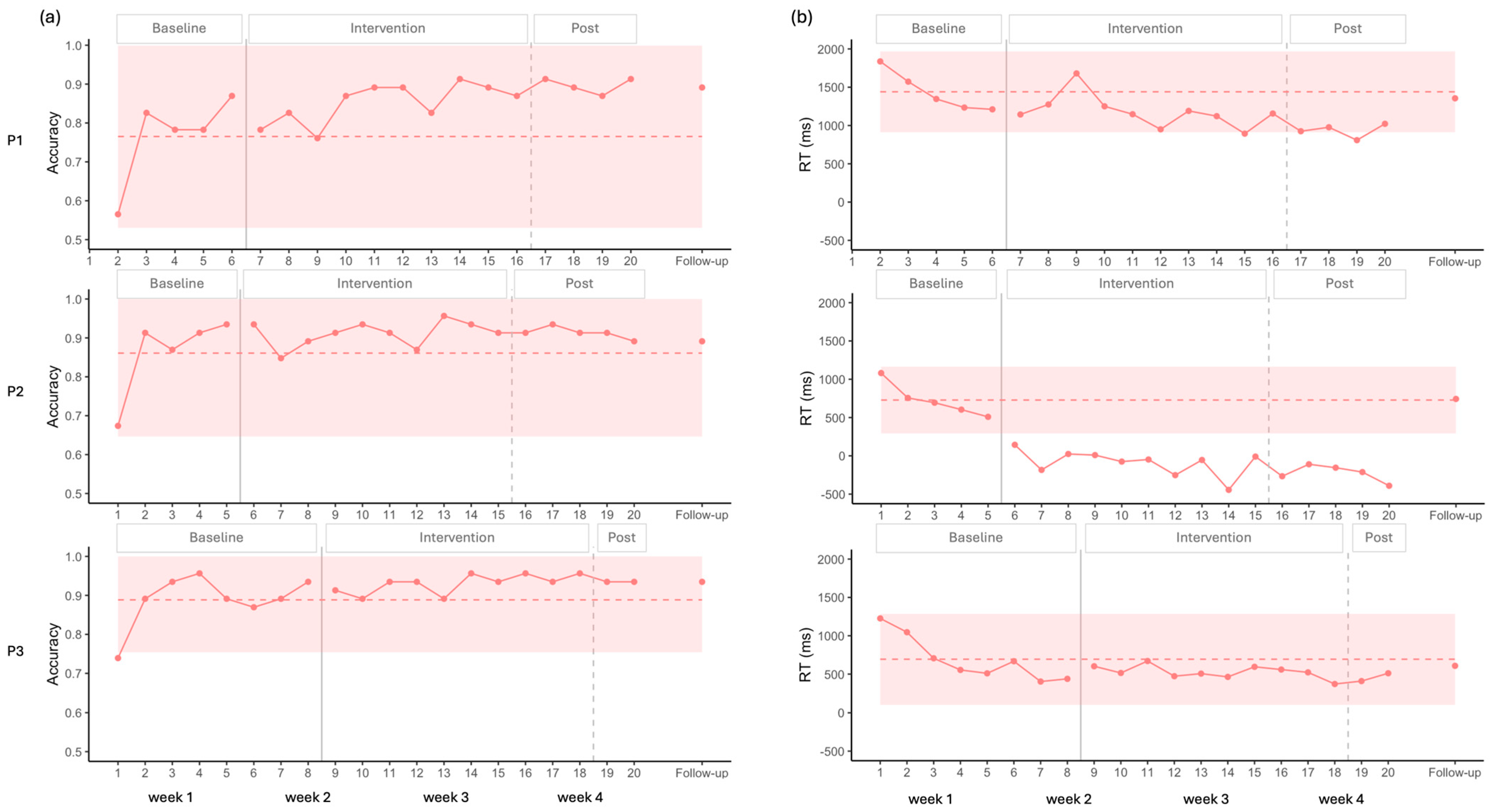

3.1.1. Picture Naming

3.1.2. Auditory Naming

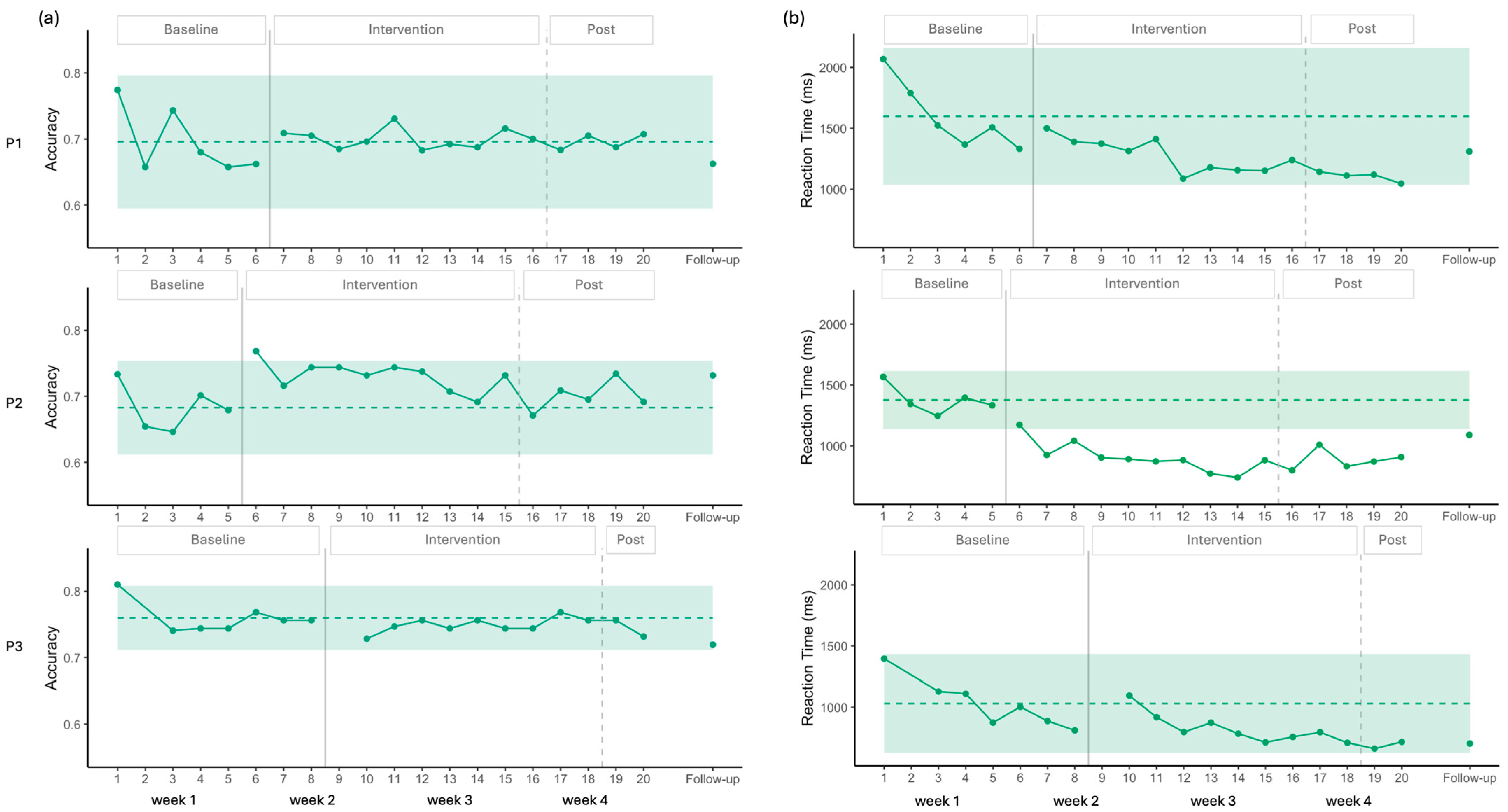

3.2. Semantic Decision

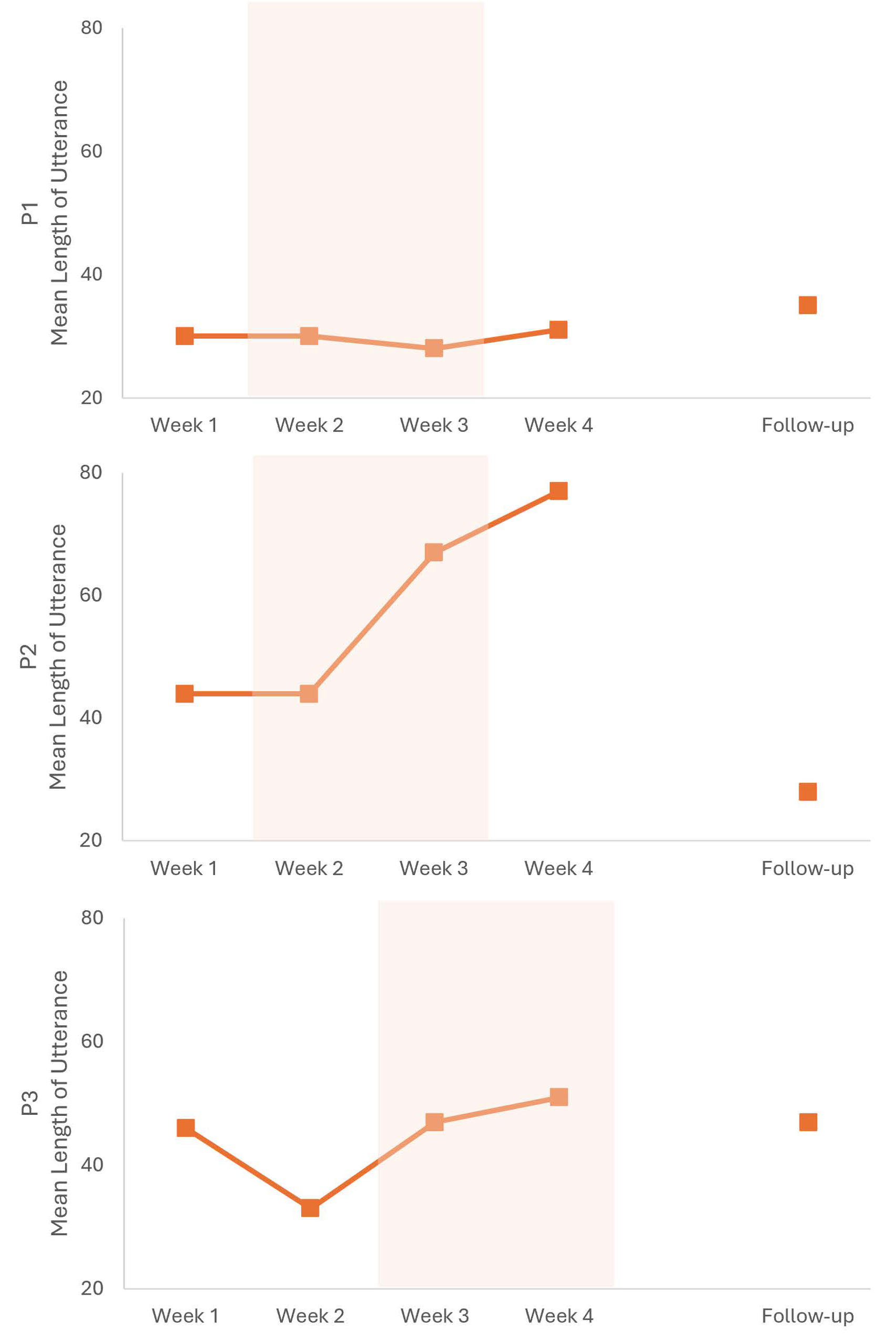

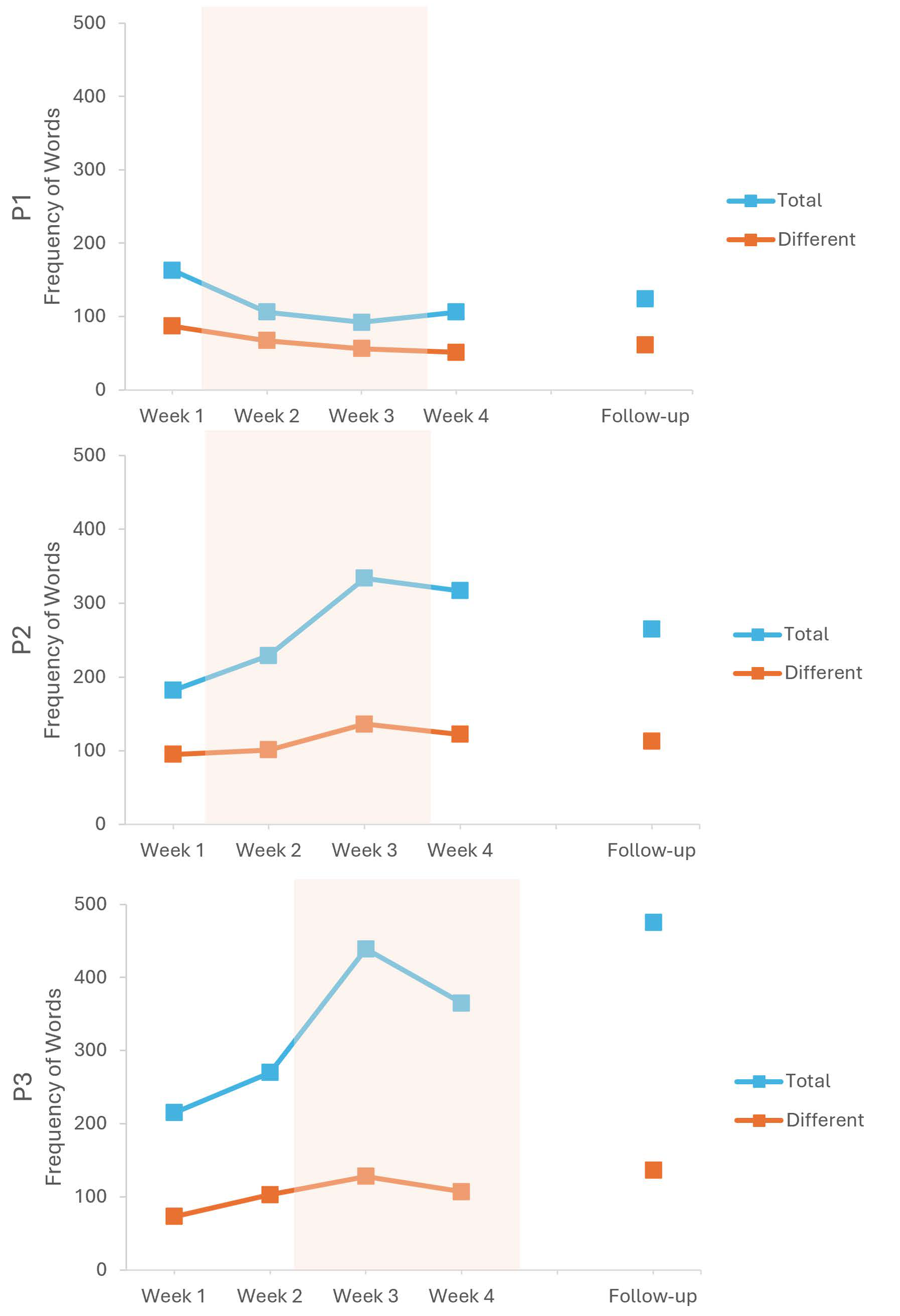

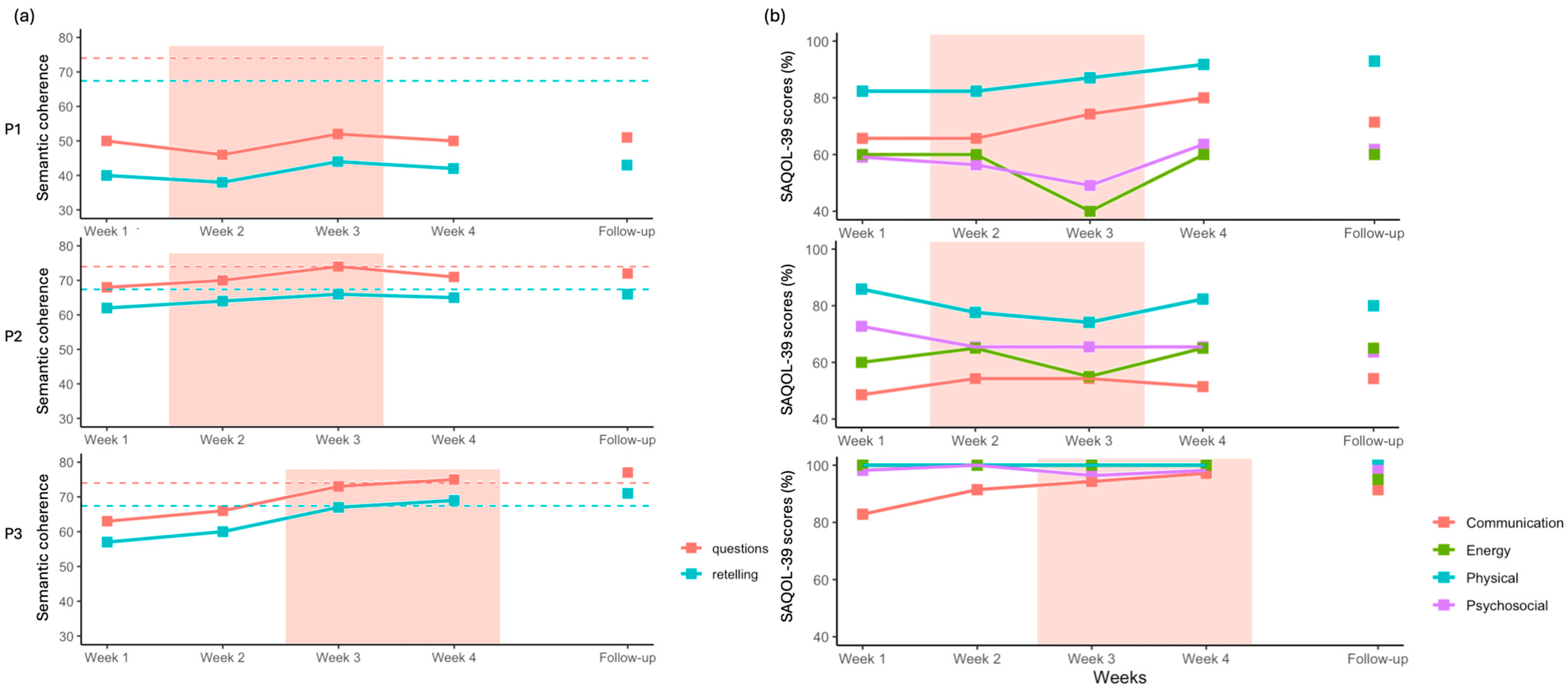

3.3. Peer Conflict Resolution

3.4. SAQOL-39

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects on Naming

4.2. Effects on Semantic Decision

4.3. Generalization and Perspectives

4.4. Combined Therapy and Long-Lasting Effects

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATL | Anterior Temporal Lobe |

| fMRI | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| IFG | Inferior Frontal Gyrus |

| MTG | Middle Temporal Gyrus |

| PCR | Peer Conflict Resolution |

| RMT | Resting Motor Threshold |

| RT | Reaction Time |

| rTMS | Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| SAQOL-39 | Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale—39 items |

| SCED | Single-Case Experimental Design |

| SES | Socioeconomic Status |

| SLT | Speech and Language Therapy |

| tDCS | Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| WAB | Western Aphasia Battery |

Appendix A

| Subtest | P1 | P2 | P3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bedside Language Score (WAB) (max = 100, sum of scores ÷ 8 × 10) | 88.75 | 92 | 91.25 |

| Spontaneous Speech: Content (max = 10) | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| Spontaneous Speech: Fluency (max = 10) | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Auditory Verbal Comprehension (max = 10) | 9 | 9 | 10 |

| Sequential Commands (max = 10) | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| Repetition (max = 10) | 9 | 7 | 7 |

| Object Naming (max = 10) | 9 | 10 | 8 |

| Reading (max = 10) | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Writing (max = 10) | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| Philadelphia Naming Test 30 | 28 | 30 | 30 |

| Picture Naming | Auditory Naming | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | Supplementary | Original | Supplementary | |

| Age of Acquisition | 4.93 (0.94) | 10.12 (1.12) | 5.98 (1.23) | 7.27 (2.98) |

| Concreteness | 4.88 (0.13) | 4.87 (0.10) | 4.77 (0.23) | 2.17 (0.45) |

| Frequency | 2.55 (0.56) | 2.09 (0.34) | 2.54 (0.48) | 3.62 (0.88) |

| Retelling | Questions | |

|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 week 1 | Score = 40 The story is severely compressed and inaccurate. Roles are reversed (Mike asks Peter to switch). Key elements are missing (grill vs. garbage, sore arm). Narrative lacks sequencing or causal structure. | Score = 50 Identifies a general issue (“not working as a team”) but not the specific conflict. Reasoning is abstract and detached from the story. Introduces extreme outcomes (“violence”) without logical connection. Some attempt at explanation, but poorly grounded. |

| Participant 1 week 2 | Score = 38 Very vague and hesitant (“I think that’s what’s that”). Reversal of who asks to switch jobs. Almost no descriptive detail or structure. | Score = 46 Emphasizes communication in general terms. Responses trail off and lose coherence. Logical connections are weak and incomplete. |

| Participant 1 week 3 | Score = 44 Corrects character names after hesitation. Basic conflict is present (request to switch, refusal). Still minimal detail, but clearer than earlier sessions. | Score = 52 Identifies refusal to switch as the problem. Reasoning is simplistic but logically consistent. Offers compromise as a solution without elaboration. |

| Participant 1 week 4 | Score = 42 Confusion about who wants to switch jobs persists. Story structure remains incomplete. Conflict is stated but not clearly framed. | Score = 50 Recognizes negotiation as a solution. Cause–effect logic is present but shallow (“that would solve the problem”). Emotional outcomes are minimally addressed. |

| Participant 1 follow-up | Score = 43 Slightly clearer sequencing. Still repetitive and lacking essential story details. | Score = 51 Identifies refusal as the core issue. Predicts emotional outcomes with basic logic. Reasoning remains generic and under-specified. |

| Participant 2 week 1 | Score = 62 Core elements are present (grill, trash, sore arm). Sequence is mostly correct. Some disfluencies and name uncertainty | Score = 68 Clearly identifies the conflict and motivations. Uses logical reasoning (entitlement, fairness). Some speculation, but reasoning remains coherent. |

| Participant 2 week 2 | Score = 64 Story elements are clearly identified. Logical sequence maintained. Slight redundancy but coherent. | Score = 70 Demonstrates boundary-setting reasoning. Clear cause–effect explanations. Occasional irrelevant speculation (personality traits). |

| Participant 2 week 3 | Score = 66 Structured retelling with clear roles and tasks. Logical progression from assignment to conflict. | Score = 74 Multiple solution pathways outlined. Strong causal reasoning and clear justification. Minor role-play digressions. |

| Participant 2 week 4 | Score = 65 Story is coherent but hesitant. Some uncertainty about outcomes. | Score = 71 Clear logical stance and conflict resolution. Reflects on uncertainty without contradiction. |

| Participant 2 follow-up | Score = 66 Accurate, well-sequenced retelling. No major inconsistencies. | Score = 72 Manager-based resolution is logically justified. Cause–effect reasoning is explicit. |

| Participant 3 week 1 | Score = 57 Story structure present but hesitant and repetitive. Confusion in phrasing and task description. | Score = 63 Identifies conflict accurately. Reasoning incomplete but logically aligned with story. |

| Participant 3 week 2 | Score = 60 Clearer and more concise. Maintains correct sequence. | Score = 66 Proposes solutions logically. Considers consequences with minimal contradiction. |

| Participant 3 week 3 | Score = 67 Complete, accurate retelling. Strong narrative structure. | Score = 73 Explores multiple solutions logically. Clear cause–effect relationships. |

| Participant 3 week 4 | Score = 69 Confident, well-structured retelling. No inconsistencies. | Score = 75 Logical, balanced reasoning. Strong justification for chosen solutions. |

| Participant 3 follow-up | Score = 71 Fully accurate, fluent, and well organized. | Score = 77 Clear problem definition. Multiple coherent solutions with closure. Explicit emotional and practical outcomes. |

| Phonological Fragments | Phrase Revisions | Pauses | Filled Pauses | Typical Disfluencies | Total Disfluencies | % Total Disfluencies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | |||||||

| Week 1 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 16 | 35 | 35 | 23.19 |

| Week 2 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 11 | 11 | 9.09 |

| Week 3 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 9.45 |

| Week 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 9.45 |

| Follow-up | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 5.81 |

| P2 | |||||||

| Week 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 26 | 29 | 29 | 12.89 |

| Week 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 27 | 33 | 33 | 11.54 |

| Week 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 20 | 28 | 29 | 6.87 |

| Week 4 | 3 | 0 | 16 | 36 | 55 | 55 | 13.72 |

| Follow-up | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.60 |

| P3 | |||||||

| Week 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Week 2 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 16 | 4.73 |

| Week 3 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 2.08 |

| Week 4 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 9 | 2.08 |

| Follow-up | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.17 |

| Different Words | Total Words | TTR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | |||

| Week 1 | 87 | 163 | 0.534 |

| Week 2 | 67 | 106 | 0.632 |

| Week 3 | 56 | 92 | 0.609 |

| Week 4 | 51 | 106 | 0.481 |

| Follow-up | 61 | 124 | 0.492 |

| P2 | |||

| Week 1 | 95 | 182 | 0.522 |

| Week 2 | 101 | 229 | 0.441 |

| Week 3 | 136 | 334 | 0.407 |

| Week 4 | 122 | 317 | 0.385 |

| Follow-up | 113 | 265 | 0.426 |

| P3 | |||

| Week 1 | 73 | 215 | 0.340 |

| Week 2 | 103 | 270 | 0.381 |

| Week 3 | 128 | 439 | 0.292 |

| Week 4 | 107 | 365 | 0.293 |

| Follow-up | 136 | 475 | 0.286 |

References

- Frederick, A.; Jacobs, M.; Adams-Mitchell, C.J.; Ellis, C. The Global Rate of Post-Stroke Aphasia. Perspect. ASHA Spec. Interest Groups 2022, 7, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.M.C.; Wodchis, W.P. The relationship of 60 disease diagnoses and 15 conditions to preference-based health-related quality of life in Ontario hospital-based long-term care residents. Med. Care 2010, 48, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, Y.; Choi, H.; Pyun, S.B. Community Integration and Quality of Life in Aphasia after Stroke. Yonsei Med. J. 2015, 56, 1694–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.C.; Ali, M.; VandenBerg, K.; Williams, L.J.; Williams, L.R.; Abo, M.; Becker, F.; Bowen, A.; Brandenburg, C.; Breitenstein, C.; et al. Precision rehabilitation for aphasia by patient age, sex, aphasia severity, and time since stroke? A prespecified, systematic review-based, individual participant data, network, subgroup meta-analysis. Int. J. Stroke 2022, 17, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arheix-Parras, S.; Barrios, C.; Python, G.; Cogné, M.; Sibon, I.; Engelhardt, M.; Dehail, P.; Cassoudesalle, H.; Moucheboeuf, G.; Glize, B. A systematic review of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in aphasia rehabilitation: Leads for future studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 212–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biou, E.; Cassoudesalle, H.; Cogné, M.; Sibon, I.; De Gabory, I.; Dehail, P.; Aupy, J.; Glize, B. Transcranial direct current stimulation in post-stroke aphasia rehabilitation: A systematic review. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 62, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.G. Inter-hemispheric inhibition sculpts the output of neural circuits by co-opting the two cerebral hemispheres. J. Physiol. 2020, 598, 4781–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefaniak, J.D.; Halai, A.D.; Lambon Ralph, M.A. The neural and neurocomputational bases of recovery from post-stroke aphasia. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefaniak, J.D.; Geranmayeh, F.; Lambon Ralph, M.A. The multidimensional nature of aphasia recovery post-stroke. Brain 2022, 145, 1354–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffau, H.; Moritz-Gasser, S.; Mandonnet, E. A re-examination of neural basis of language processing: Proposal of a dynamic hodotopical model from data provided by brain stimulation mapping during picture naming. Brain Lang. 2014, 131, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresang, H.C.; Harvey, D.Y.; Vnenchak, L.; Parchure, S.; Cason, S.; Twigg, P.; Faseyitan, O.; Maher, L.M.; Hamilton, R.H.; Coslett, H.B. Semantic and Phonological Abilities Inform Efficacy of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Sustained Aphasia Treatment Outcomes. Neurobiol. Lang. 2025, 6, nol_a_00160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, A.; Schwartz, M.F.; Martin, N.; Grewal, R.S.; Brecher, A. The Philadelphia naming test: Scoring and rationale. Clin. Aphasiology 1996, 24, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Arheix-Parras, S.; Franco, J.; Siklafidou, I.; Villain, M.; Rogue, C.; Python, G.; Glize, B. Neuromodulation of the Right Motor Cortex of the Lips with Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation to Reduce Phonological Impairment and Improve Naming in Three Persons with Aphasia: A Single-Case Experimental Design. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2024, 33, 2023–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridding, M.C.; Rothwell, J.C. Is there a future for therapeutic use of transcranial magnetic stimulation? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, A.E.; Caramazza, A. Converging evidence for the interaction of semantic and sublexical phonological information in accessing lexical representations for spoken output. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 1995, 12, 187–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, J.R.; Desai, R.H. The neurobiology of semantic memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambon Ralph, M.A.; Jefferies, E.; Patterson, K.; Rogers, T.T. The neural and computational bases of semantic cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2017, 18, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, K.; Kopelman, M.D.; Woollams, A.M.; Brownsett, S.L.; Geranmayeh, F.; Wise, R.J. Semantic memory: Which side are you on? Neuropsychologia 2015, 76, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binder, J.R.; Desai, R.H.; Graves, W.W.; Conant, L.L. Where Is the Semantic System? A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis of 120 Functional Neuroimaging Studies. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 2767–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, R.C. The Assessment and Analysis of Handedness: The Edinburgh Inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971, 9, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Antal, A.; Bestmann, S.; Bikson, M.; Brewer, C.; Brockmöller, J.; Carpenter, L.L.; Cincotta, M.; Chen, R.; Daskalakis, J.D.; et al. Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: Expert Guidelines. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 269–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kertesz, A. Western Aphasia Battery—Revised. APA PsycNet 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.M.; Schwartz, M.F. Short-form Philadelphia naming test: Rationale and empirical evaluation. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2012, 21, S140–S153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny-Pacini, A.; Evans, J. Single-case experimental designs to assess intervention effectiveness in rehabilitation: A practical guide. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 61, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochwill, T.R.; Hitchcock, J.H.; Horner, R.H.; Levin, J.R.; Odom, S.L.; Rindskopf, D.M.; Shadish, W.R. Single-Case Intervention Research Design Standards. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2013, 34, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilari, K.; Byng, S.; Lamping, D.L.; Smith, S.C. Stroke and Aphasia Quality of Life Scale-39 (SAQOL-39): Evaluation of Acceptability, Reliability, and Validity. Stroke 2003, 34, 1944–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nippold, M.A.; Mansfield, T.C.; Billow, J.L. Peer Conflict Explanations in Children, Adolescents, and Adults: Examining the Development of Complex Syntax. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2007, 16, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberger, M.J.; Heydari, N.; Caccappolo, E.; Seidel, W.T. Naming in Older Adults: Complementary Auditory and Visual Assessment. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2022, 28, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperman, V.; Stadthagen-Gonzalez, H.; Brysbaert, M. Age-of-acquision ratings for 30 thousand English words. Behav. Res. Methods 2012, 44, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brysbaert, M.; Warriner, A.; Kuperman, V. Concreteness ratings for 40 thousand generally known English word lemmas. Behav. Res. Methods 2014, 46, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M.; New, B. Moving beyond Kucera and Francis: A critical evaluation of current word frequency norms and the introduction of a new and improved word frequency measure for American English. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S.C.; Teghipco, A.; Sayers, S.; Newman-Norlund, R.; Newman-Norlund, S.; Fridriksson, J. Story Recall in Peer Conflict Resolution Discourse Task to Identify Older Adults Testing Within Range of Cognitive Impairment. Am. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2024, 33, 2582–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macwhinney, B.; Fromm, D.; Forbes, M.; Holland, A. AphasiaBank: Methods for Studying Discourse. Aphasiology 2011, 25, 1286–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macwhinney, B. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk; Lawrence Erlbaum Associate: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman-Norlund, R.D.; Newman-Norlund, S.E.; Sayers, S.; Nemati, S.; Riccardi, N.; Rorden, C.; Fridriksson, J. The Aging Brain Cohort (ABC) repository: The University of South Carolina’s multimodal lifespan database for studying the relationship between the brain, cognition, genetics and behavior in healthy aging. Neuroimage Rep. 2021, 1, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bedirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protopapas, A. CheckVocal: A program to facilitate checking the accuracy and response time of vocal responses from DMDX. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tate, R.; Perdices, M. Single-Case Experimental Designs for Clinical Research and Neurorehabilitation Settings: Planning, Conduct, Analysis and Reporting; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vannest, K.J.; Ninci, J. Evaluating Intervention Effects in Single-Case Research Designs. J. Couns. Dev. 2015, 93, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarlow, K.R. An Improved Rank Correlation Effect Size Statistic for Single-Case Designs: Baseline Corrected Tau. Behav. Modif. 2016, 41, 427–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piai, V.; Eikelboom, D. Brain Areas Critical for Picture Naming: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Lesion-Symptom Mapping Studies. Neurobiol. Lang. 2023, 4, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobric, G.; Jefferies, E.; Ralph, M.A. Anterior temporal lobes mediate semantic representation: Mimicking semantic dementia by using rTMS in normal participants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 20137–20141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.-F.; Yeh, S.-C.; Kao, Y.-C.J.; Lu, C.-F.; Tsai, P.-Y. Functional Remodeling Associated with Language Recovery After Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Chronic Aphasic Stroke. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 809843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.; Caltagirone, C.; Marangolo, P. Combining Voxel-based Lesion-symptom Mapping (VLSM) With A-tDCS Language Treatment: Predicting Outcome of Recovery in Nonfluent Chronic Aphasia. Brain Stimul. 2015, 8, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilha, L.; Rorden, C.; Roth, R.; Sen, S.; George, M.; Fridriksson, J. Improved naming in patients with Broca’s aphasia with tDCS. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2024, 95, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.L.; Hoffman, P.; Pobric, G.; Lambon Ralph, M.A. The Semantic Network at Work and Rest: Differential Connectivity of Anterior Temporal Lobe Subregions. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 1490–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papinutto, N.; Galantucci, S.; Mandelli, M.L.; Gesierich, B.; Jovicich, J.; Caverzasi, E.; Henry, R.G.; Seeley, W.W.; Miller, B.L.; Shapiro, K.A.; et al. Structural connectivity of the human anterior temporal lobe: A diffusion magnetic resonance imaging study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016, 37, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, S.R.; Babu, P.; Paplikar, A. Aphasia severity and factors predicting language recovery in the chronic stage of stroke. Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2025, 60, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, A.M.; Kambanaros, M. The Effectiveness of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) Paradigms as Treatment Options for Recovery of Language Deficits in Chronic Poststroke Aphasia. Behav. Neurol. 2022, 2022, 7274115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahmy, E.; Elshebawy, H. Effect of High Frequency Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Recovery of Chronic Post-Stroke Aphasia. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 30, 105855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, T.; Wang, J.; Lin, M.; Tsai, P. Low-Frequency vs. Theta Burst Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for the Treatment of Chronic Non-fluent Aphasia in Stroke: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 13, 800377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, Q.; Brenya, J.; Chavaria, K.; Friest, A.; Ahmad, N.; Zorns, S.; Vaidya, S.; Shelanskey, T.; Sierra, S.; Ash, S.; et al. The Sol Braiding Method for Handling Thick Hair During Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: An Address for Potential Bias in Brain Stimulation. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2024, 210, e66001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebner, H.R.; Funke, K.; Aberra, A.S.; Antal, A.; Bestmann, S.; Chen, R.; Classen, J.; Davare, M.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Fox, P.T.; et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the brain: What is stimulated?—A consensus and critical position paper. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 140, 59–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Gender | Age at Inclusion | Highest Level of Education Completed | Last or Current Occupation | SES 1 Scores (Hollingshead) | Time Post-Onset (Months) | Type of Stroke |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | M | 68 | MD (Doctor of Medicine) | Ophthalmologist (last) | 66 | 36 | Ischemic |

| P2 | M | 45 | PhD | Professor of history (last) | 66 | 68 | Ischemic |

| P3 | W | 44 | JD (Juris Doctor) | Lawyer (current) | 66 | 52 | Ischemic |

| Task | Measure | Effect Size | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | P2 | P3 | ||

| Picture Naming | Accuracy | Tau = 0.703 p = 0.001, SETau = 0.225 | Tau = 0.346 p = 0.099, SETau = 0.297 | Tau = 0.569 p = 0.006, SETau = 0.260 |

| RT | Tau = −0.665 p = 0.001, SETau = 0.236 | Tau = −0.578 p = 0.003, SETau = 0.258 | Tau = −0.355 p = 0.070, SETau = 0.296 | |

| Auditory Naming | Accuracy | Tau = 0.459 p = 0.031, SETau = 0.288 | Tau = 0.189 p = 0.387, SETau = 0.311 | Tau = 0.380 p = 0.076, SETau = 0.292 |

| RT | BCTau = 0.640 p = 0.001, SETau = 0.249 | BC Tau = 0.008 p = 1.000, SETau = 0.316 | BC Tau = 0.711 p = 0.000, SETau = 0.222 | |

| Semantic Decision | Accuracy | Tau = 0.387 p = 0.057, SETau = 0.299 | Tau = 0.399 p = 0.044, SETau = 0.290 | Tau = −0.162 p = 0.484, SETau = 0.329 |

| RT | Tau = −0.494 p = 0.014, SETau = 0.282 | Tau = −0.628 p = 0.001, SETau = 0.246 | BC Tau = 0.712 p = 0.001, SETau = 0.234 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arheix-Parras, S.; Moore, S.R.; Desai, R.H. Improving Lexicosemantic Impairments in Post-Stroke Aphasia Using rTMS Targeting the Right Anterior Temporal Lobe. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010117

Arheix-Parras S, Moore SR, Desai RH. Improving Lexicosemantic Impairments in Post-Stroke Aphasia Using rTMS Targeting the Right Anterior Temporal Lobe. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleArheix-Parras, Sophie, Sophia R. Moore, and Rutvik H. Desai. 2026. "Improving Lexicosemantic Impairments in Post-Stroke Aphasia Using rTMS Targeting the Right Anterior Temporal Lobe" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010117

APA StyleArheix-Parras, S., Moore, S. R., & Desai, R. H. (2026). Improving Lexicosemantic Impairments in Post-Stroke Aphasia Using rTMS Targeting the Right Anterior Temporal Lobe. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010117