Facilitating Novice Visual Search with tES over rIFG: Baseline-Dependent Gains in Target Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

| Variable | Total (n = 64) | tDCS (n = 20) | hf-tRNS (n = 21) | Control (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 22.33 (6.05) | 22.95 (5.62) | 23.50 (5.25) | 21.74 (5.25) |

| Male, n (%) | 31 (48) | 8 (40) | 8 (38) | 15 (65) |

| Female, n (%) | 33 (52) | 12 (60) | 13 (62) | 8 (35) |

2.2. SAR Task

2.3. Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (tES)

- tDCS condition: 2.0 mA DC current alone.

- hf-tRNS condition: random noise (100–500 Hz, ±0.18 mA) combined with a 1.8 mA DC offset.

- Low-current control condition: 0.1 mA DC current alone.

2.4. Randomization, Blinding, and Sensation Ratings

2.5. EEG Acquisition and Analysis

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics and Blinding

3.2. Behavioral Performance

3.2.1. Overall Accuracy

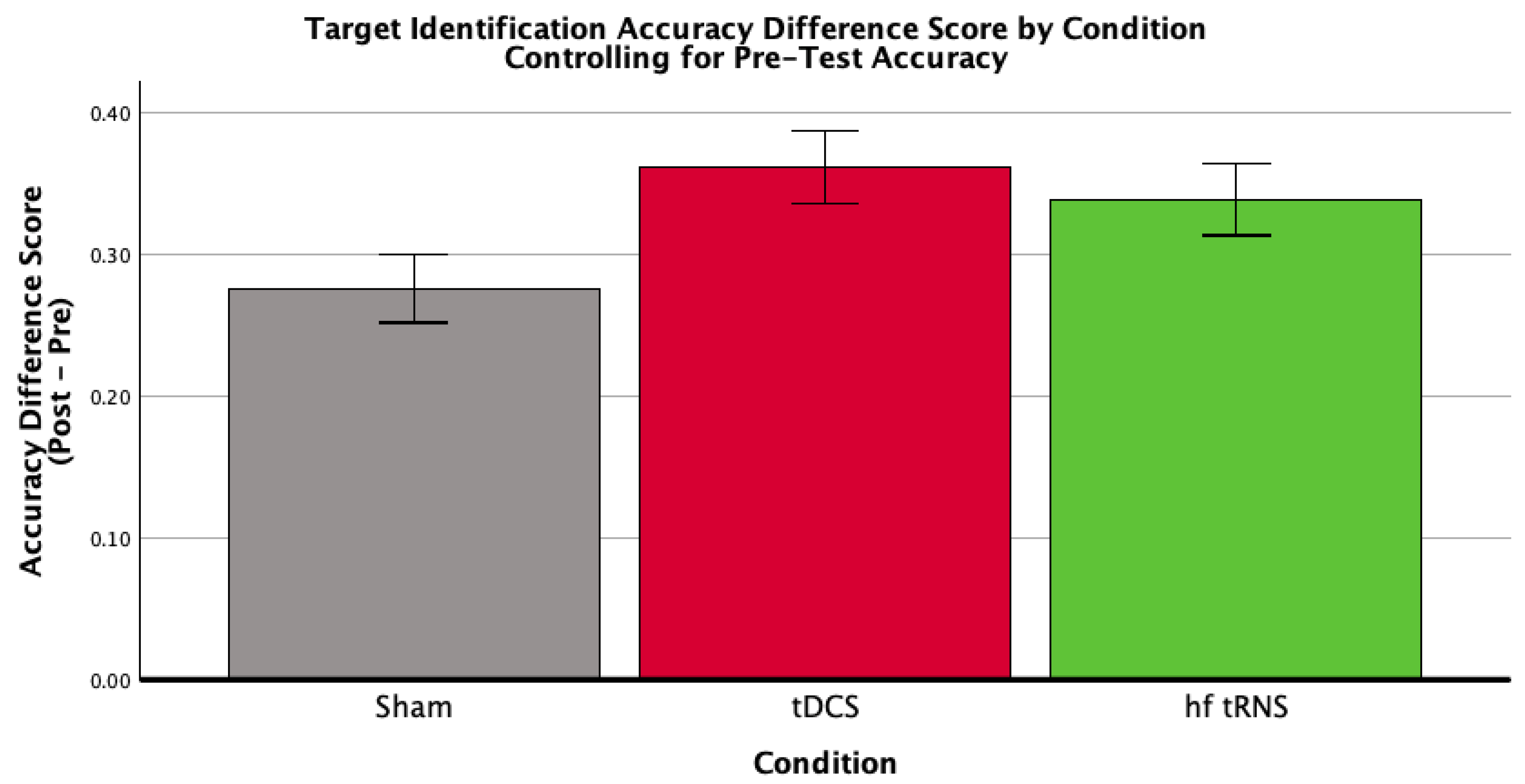

3.2.2. Target Identification

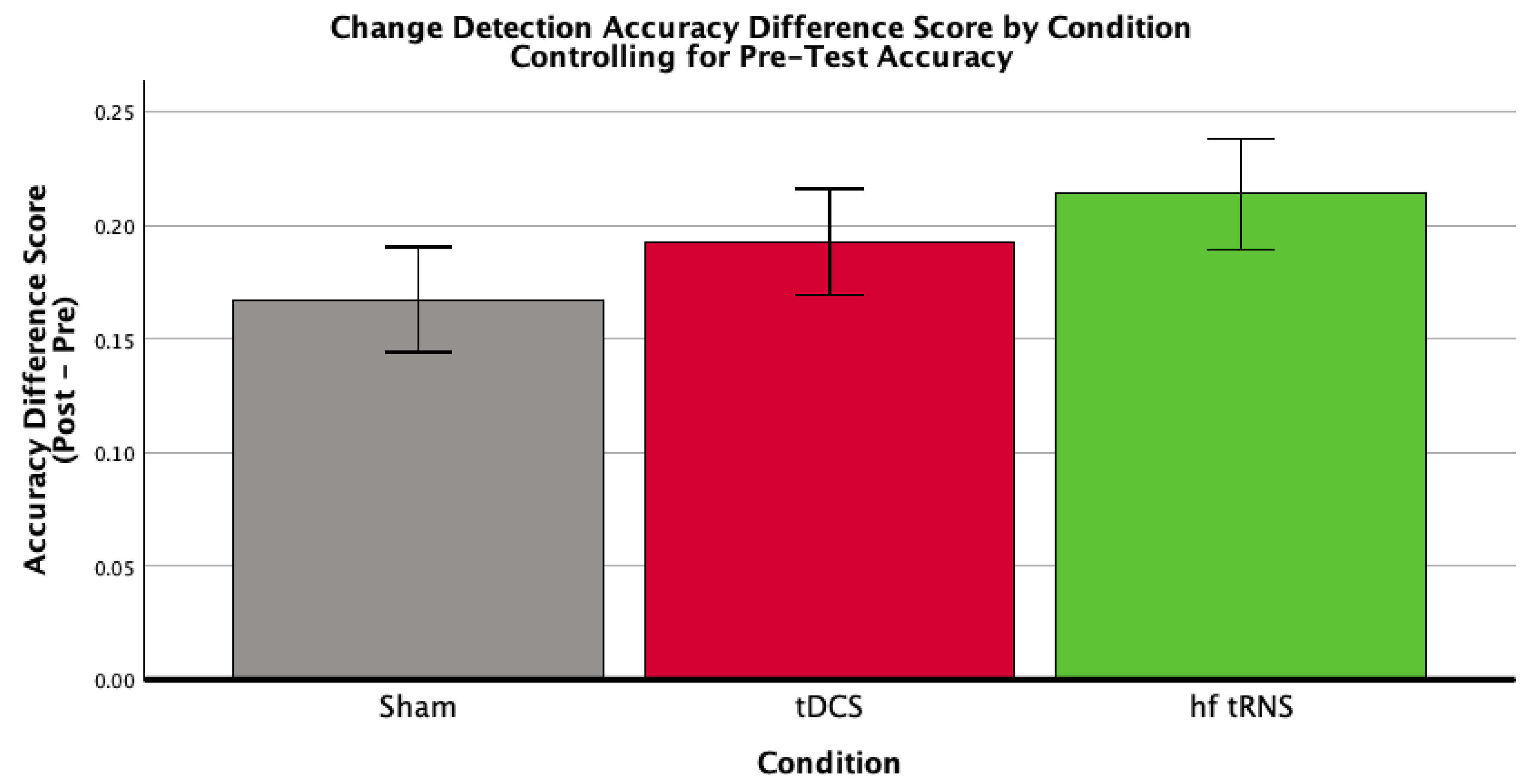

3.2.3. Change Detection

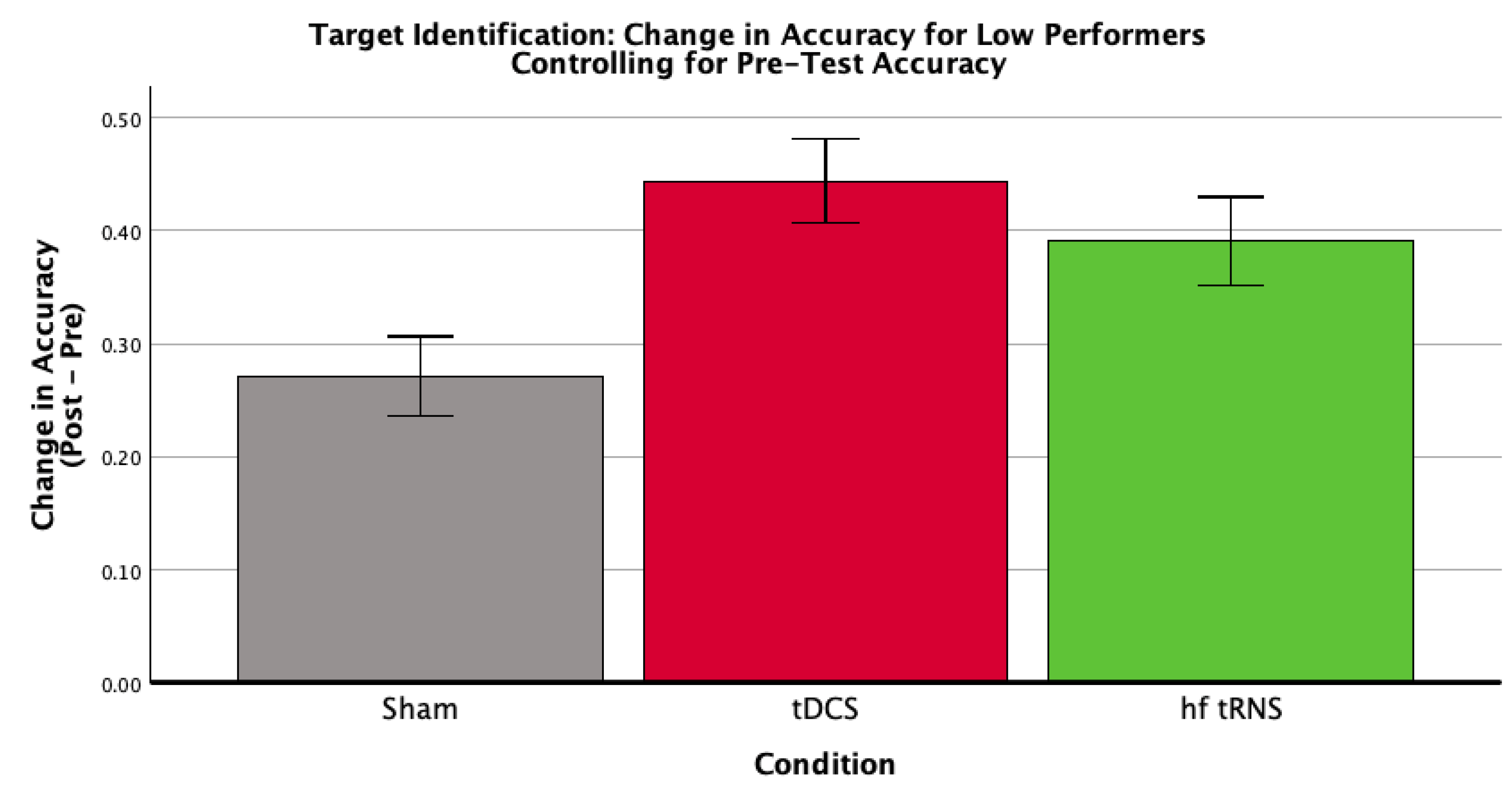

3.3. Baseline Performance Moderation

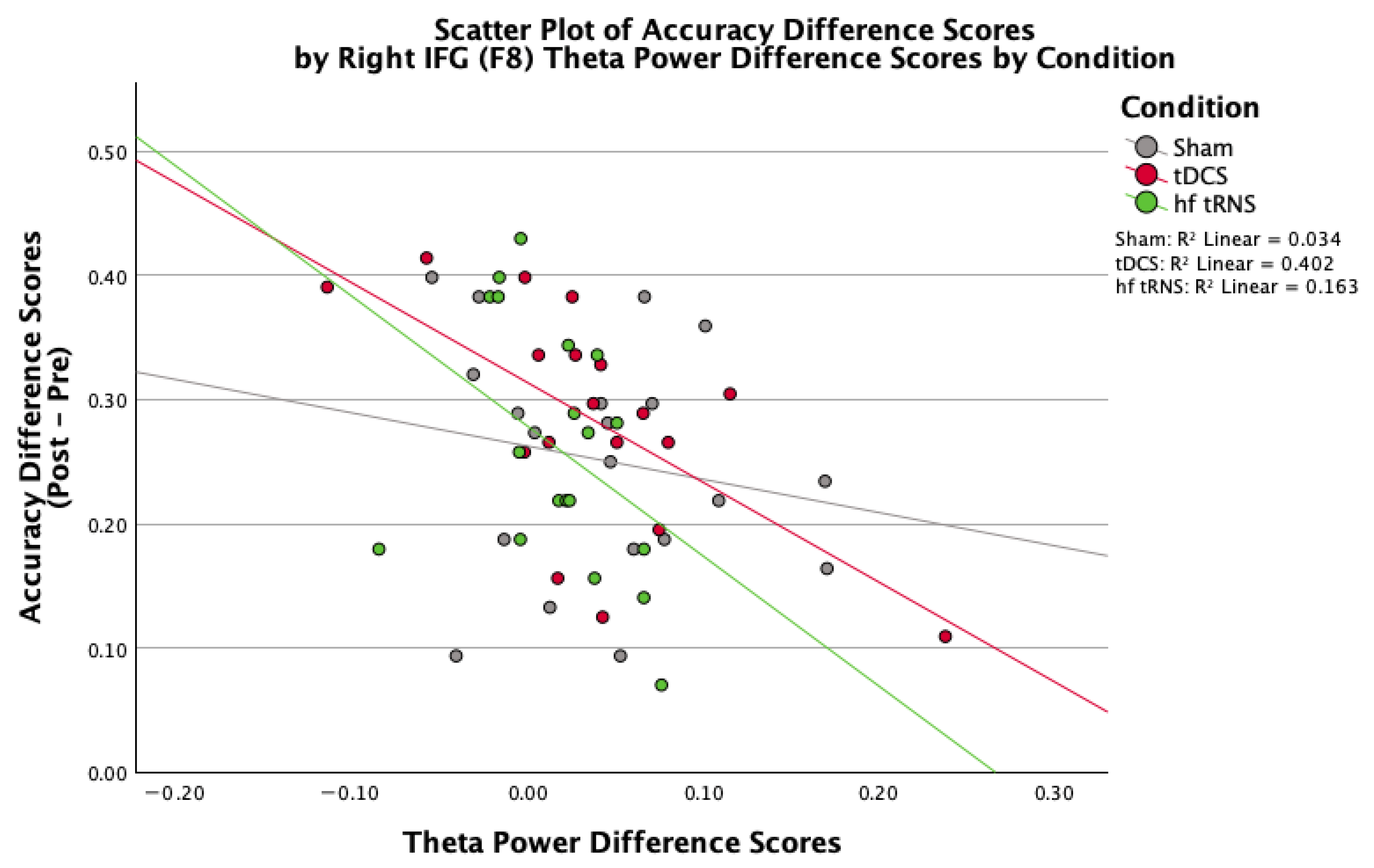

3.4. EEG Measures

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| tES | Transcranial electrical stimulation |

| tDCS | Transcranial direct current stimulation |

| hf-tRNS | High-frequency transcranial random noise stimulation |

| rIFG | Right inferior frontal gyrus |

| SAR | Synthetic aperture radar |

| IPS | Intraparietal sulcus |

| FEF | Frontal eye fields |

| DLPFC | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

| UNM | University of New Mexico |

References

- Wolfe, J.M. Guided search 4.0. In Integrated Models of Cognitive Systems; Gray, W., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bisley, J.W. The neural basis of visual attention. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschman, T.J.; Miller, E.K. Top-down versus bottom-up control of attention in the prefrontal and posterior parietal cortices. Science 2007, 315, 1860–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, J.J.; Behrmann, M. Selective visual attention and visual search: Behavioral and neural mechanisms. Psychol. Learn. Motiv. 2003, 42, 157–191. [Google Scholar]

- Warm, J.S.; Parasuraman, R.; Matthews, G. Vigilance requires hard mental work and is stressful. Hum. Factors 2008, 50, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J. Physiol. 2000, 527, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terney, D.; Chaieb, L.; Moliadze, V.; Antal, A.; Paulus, W. Increasing human brain excitability by transcranial high-frequency random noise stimulation. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 14147–14155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertonani, A.; Miniussi, C. Transcranial electrical stimulation: What we know and do not know about mechanisms. Neuroscientist 2017, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, V.P.; Coffman, B.A.; Mayer, A.R.; Weisend, M.P.; Lane, T.D.R.; Calhoun, V.D.; Raybourn, E.M.; Garcia, C.M.; Wassermann, E.M. TDCS guided using fMRI significantly accelerates learning to identify concealed objects. NeuroImage 2012, 59, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, B.C.; Mullins, T.S.; Heinrich, M.D.; Witkiewitz, K.; Yu, A.B.; Hansberger, J.T.; Clark, V.P. Transcranial direct current stimulation facilitates category learning. Brain Stimul. 2020, 13, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filmer, H.L.; Mattingley, J.B.; Dux, P.E. Modulating brain activity and behaviour with tDCS: Rumours of its death have been greatly exaggerated. Cortex 2019, 123, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, B.; Cohen Kadosh, R. Not all brains are created equal: The relevance of individual differences in responsiveness to transcranial electrical stimulation. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarnecchi, E.; Brem, A.K.; Levenbaum, E.; Thompson, T.; Kadosh, R.C.; Pascual-Leone, A. Enhancing cognition using transcranial electrical stimulation. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 4, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fertonani, A.; Pirulli, C.; Miniussi, C. Random noise stimulation improves neuroplasticity in perceptual learning. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 15416–15423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, B.A.; Hunter, M.A.; Jones, A.P.; Saxon, H.A.; Kolodjeski, K.; Lockmiller, B.; Khan, O.; Collar, T.; Stephen, J.M.; Clark, V.P. Using independent components analysis (ICA) to remove artifacts associated with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) from electroencephalography (EEG) data: A comparison of ICA algorithms. Brain Stimul. Basic. Transl. Clin. Res. Neuromodulation 2014, 7, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Groen, O.; Wenderoth, N. Transcranial random noise stimulation of visual cortex: Stochastic resonance enhances central mechanisms of perception. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 5289–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulus, W.; Nitsche, M.A.; Antal, A. Application of transcranial electric stimulation (tDCS, tACS, tRNS). From Motor-Evoked Potentials Towards Modulation of Behaviour. Eur. Psychol. 2016, 2, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpich, F.; Melnick, M.D.; Agosta, S.; Huxlin, K.R.; Tadin, D.; Battelli, L. Boosting learning efficacy with noninvasive brain stimulation in intact and brain-damaged humans. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 5551–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenot, Q.; Hamery, C.; Lepron, E.; Besson, P.; De Boissezon, X.; Perrey, S.; Scannella, S. Performance after training in a complex cognitive task is enhanced by high-definition transcranial random noise stimulation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.R.; Robbins, T.W.; Poldrack, R.A. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2004, 8, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinley, R.A.; McIntire, L.; Bridges, N.; Goodyear, C.; Bangera, N.B.; Weisend, M.P. Acceleration of image analyst training with transcranial direct current stimulation. Behav. Neurosci. 2013, 127, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.P.; Bryant, N.B.; Robert, B.M.; Mullins, T.S.; Trumbo, M.C.S.; Ketz, N.A.; Howard, M.D.; Pilly, P.K.; Clark, V.P. Closed-loop tACS delivered during slow-wave sleep reduces retroactive interference on a paired-associates learning task. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The MathWorks Inc. MATLAB, version 9.6 (R2019a); The MathWorks Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2019.

- Rensink, R.A. Change detection. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, J.F.; Frank, M.J. Frontal theta as a mechanism for cognitive control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014, 18, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Condition | Tingling T1 | Tingling T2 | Itching T1 | Itching T2 | Heat T1 | Heat T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.29 (±1.68) | 0.76 (±1.30) | 1.24 (±1.76) | 0.71 (±1.23) | 0.24 (±0.54) | 0.29 (±0.78) |

| tDCS | 3.10 (±1.94) | 1.55 (±1.57) | 3.05 (±1.91) | 2.05 (±1.70) | 2.45 (±2.21) | 1.10 (±1.25) |

| hf-tRNS | 2.84 (±1.89) | 1.63 (±1.54) | 3.21 (±1.75) | 2.11 (±1.20) | 1.63 (±1.71) | 0.95 (±1.27) |

| Condition | Mean Pre-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Post-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Difference Score (SD) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.313 (0.097) | 0.551 (0.142) | 0.238 (0.117) | 23 |

| tDCS | 0.340 (0.062) | 0.625 (0.055) | 0.284 (0.086) | 20 |

| hf-tRNS | 0.394 (0.079) | 0.646 (0.079) | 0.251 (0.099) | 21 |

| Total | 0.348 (0.087) | 0.605 (0.108) | 0.257 (0.102) | 64 |

| Condition | Mean Pre-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Post-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Difference Score (SD) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.307 (0.119) | 0.597 (0.139) | 0.290 (0.160) | 23 |

| tDCS | 0.307 (0.096) | 0.683 (0.093) | 0.376 (0.135) | 20 |

| hf-tRNS | 0.353 (0.126) | 0.662 (0.099) | 0.310 (0.172) | 21 |

| Total | 0.322 (0.115) | 0.645 (0.118) | 0.323 (0.159) | 64 |

| Condition | Mean Pre-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Post-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Difference Score (SD) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.319 (0.119) | 0.505 (0.162) | 0.185 (0.117) | 23 |

| tDCS | 0.373 (0.072) | 0.566 (0.103) | 0.193 (0.112) | 20 |

| hf-tRNS | 0.436 (0.102) | 0.630 (0.090) | 0.193 (0.098) | 21 |

| Total | 0.375 (0.110) | 0.565 (0.133) | 0.190 (0.108) | 64 |

| Condition | Mean Pre-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Post-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Difference Score (SD) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.236 (0.041) | 0.479 (0.139) | 0.243 (0.125) | 11 |

| tDCS | 0.296 (0.045) | 0.638 (0.046) | 0.341 (0.052) | 10 |

| hf-tRNS | 0.322 (0.052) | 0.619 (0.086) | 0.297 (0.120) | 9 |

| Total | 0.282 (0.058) | 0.574 (0.122) | 0.292 (0.109) | 30 |

| Condition | Mean Pre-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Post-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Difference Score (SD) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.251 (0.080) | 0.528 (0.132) | 0.277 (0.167) | 11 |

| tDCS | 0.256 (0.081) | 0.700 (0.112) | 0.444 (0.104) | 10 |

| hf-tRNS | 0.262 (0.120) | 0.646 (0.097) | 0.384 (0.196) | 9 |

| Total | 0.256 (0.091) | 0.621 (0.135) | 0.365 (0.169) | 30 |

| Condition | Mean Pre-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Post-Test Accuracy (SD) | Mean Difference Score (SD) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.220 (0.085) | 0.429 (0.165) | 0.209 (0.118) | 11 |

| tDCS | 0.336 (0.059) | 0.575 (0.114) | 0.239 (0.127) | 10 |

| hf-tRNS | 0.382 (0.088) | 0.592 (0.102) | 0.210 (0.115) | 9 |

| Total | 0.307 (0.103) | 0.527 (0.148) | 0.219 (0.117) | 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Robert, B.M.; Winder, A.; Briggs, M.S.; Atencio, G.I.; Clark, V.P. Facilitating Novice Visual Search with tES over rIFG: Baseline-Dependent Gains in Target Identification. Brain Sci. 2026, 16, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010001

Robert BM, Winder A, Briggs MS, Atencio GI, Clark VP. Facilitating Novice Visual Search with tES over rIFG: Baseline-Dependent Gains in Target Identification. Brain Sciences. 2026; 16(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobert, Bradley M., Aaron Winder, Mason S. Briggs, Gabriella I. Atencio, and Vincent P. Clark. 2026. "Facilitating Novice Visual Search with tES over rIFG: Baseline-Dependent Gains in Target Identification" Brain Sciences 16, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010001

APA StyleRobert, B. M., Winder, A., Briggs, M. S., Atencio, G. I., & Clark, V. P. (2026). Facilitating Novice Visual Search with tES over rIFG: Baseline-Dependent Gains in Target Identification. Brain Sciences, 16(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci16010001