Adaptation of Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia to Norwegian

Abstract

1. Introduction

Cultural Adaptation

- Can the BCPPA be adapted to a Norwegian population whilst retaining the core components of the original BCPPA intervention?

- Is the BCPPA acceptable to Norwegian PwPPA and their CPs?

- How can we measure whether the BCPPA has a positive impact on everyday conversations between Norwegian PwPPA and their CPs in terms of goal attainment, conversation behaviours, communication-related quality of life, and communication effectiveness?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia

2.2. Translation

2.3. Fidelity to Core Components

2.4. Pilot

2.4.1. Participants

2.4.2. Acceptability

2.4.3. Measuring Change for Norwegian Dyads Receiving the BCPPA

2.4.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Acceptability of the Norwegian BCPPA

3.1.1. Recruitment and Retention

3.1.2. Content Analysis of Semi-Structured Interviews

- 1.

- Awareness of how communication works: The CPs emphasised increased awareness of how they communicate and how communication works in general:“To become more aware of it, to analyse what is happening in the conversation, that well, to become more aware” (CP3);

- 2.

- Communication strategies: The PwPPA and CPs highlighted identifying and practising communication strategies as one of the most useful aspects of the BCPPA. One of the participants described how she had started describing a word when encountering a word search:“And then I have this lovely talking around talking (…) before I could not say it, but now I can talk around” (PPA1);

- 3.

- The amount of work: Even though all of the participants reported the BCPPA to be useful and that they would do it again, some reported it was hard to find time to do home-based tasks:“It helps [home-based tasks] because you have to just do it, deal with things right now.” (PPA1) “yes, yes, yes home-based tasks can be a bit difficult (…) it’s always something happening but it is useful so we try to do it even though we don’t always manage to.” (CP1).For some participants, sessions every week were too intensive, and they suggested a more distributed schedule but with more sessions, “and that it was not that often, but maybe one more time and then with more time between” (CP3). Others found four weekly sessions acceptable, saying “it was okay” (PPA4);

- 4.

- Unfamiliar terminology: The participants expressed uncertainty about some of the terminology:“You use this professional language that we don’t know. I think you should use normal language” (CP2).“I mean intonation (…) and turn-taking I think you can do that [the translation] a bit differently.” (PPA1);

- 5.

- The BCPPA provides a different perspective: The CPs reported that the BCPPA intervention made them realise that they had to change their own communication behaviour.“When things are difficult and we [as a couple] work well enough together, even if we don’t talk all the time, right? It gets very quiet after a while and then you get used to it (…) so I think it has been very good to participate” (CP3).They also pointed out that the BCPPA offered a different perspective on PPA “because it’s everything medical, the geriatrician was amazing, he had a lot of time for us, but the how it affects us in everyday life. That it is difficulties with communication, how yes what we can do, techniques and such” (CP4), and further, how it provided a place for talking about how PPA impacts life. “Kind of holding the space for us to confront those kinds of painful realities” (CP4).

3.2. Measuring the Impact of BCPPA on Everyday Conversations Between Norwegian PwPPA and Their CPs

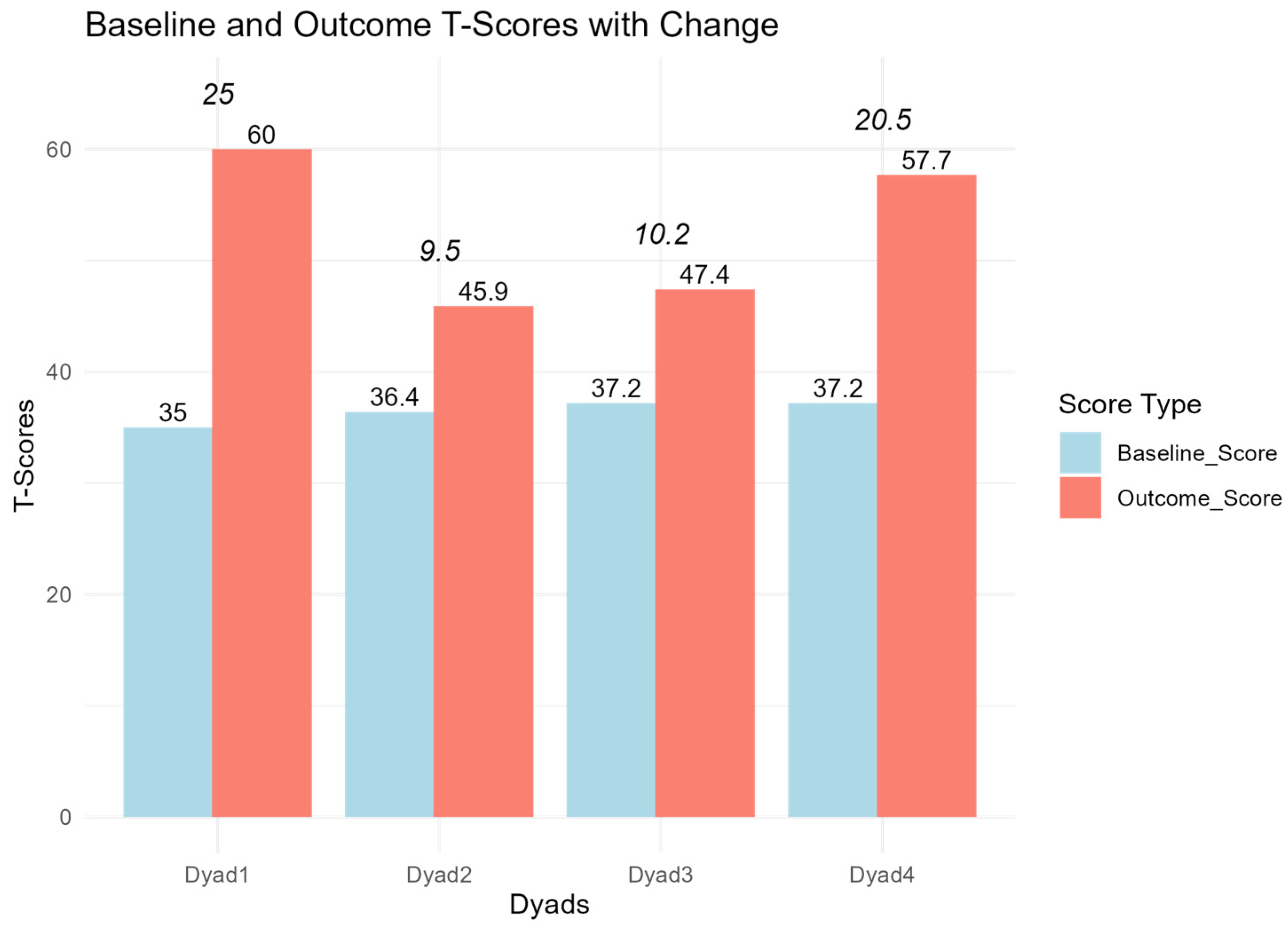

3.2.1. Goal Attainment Scaling

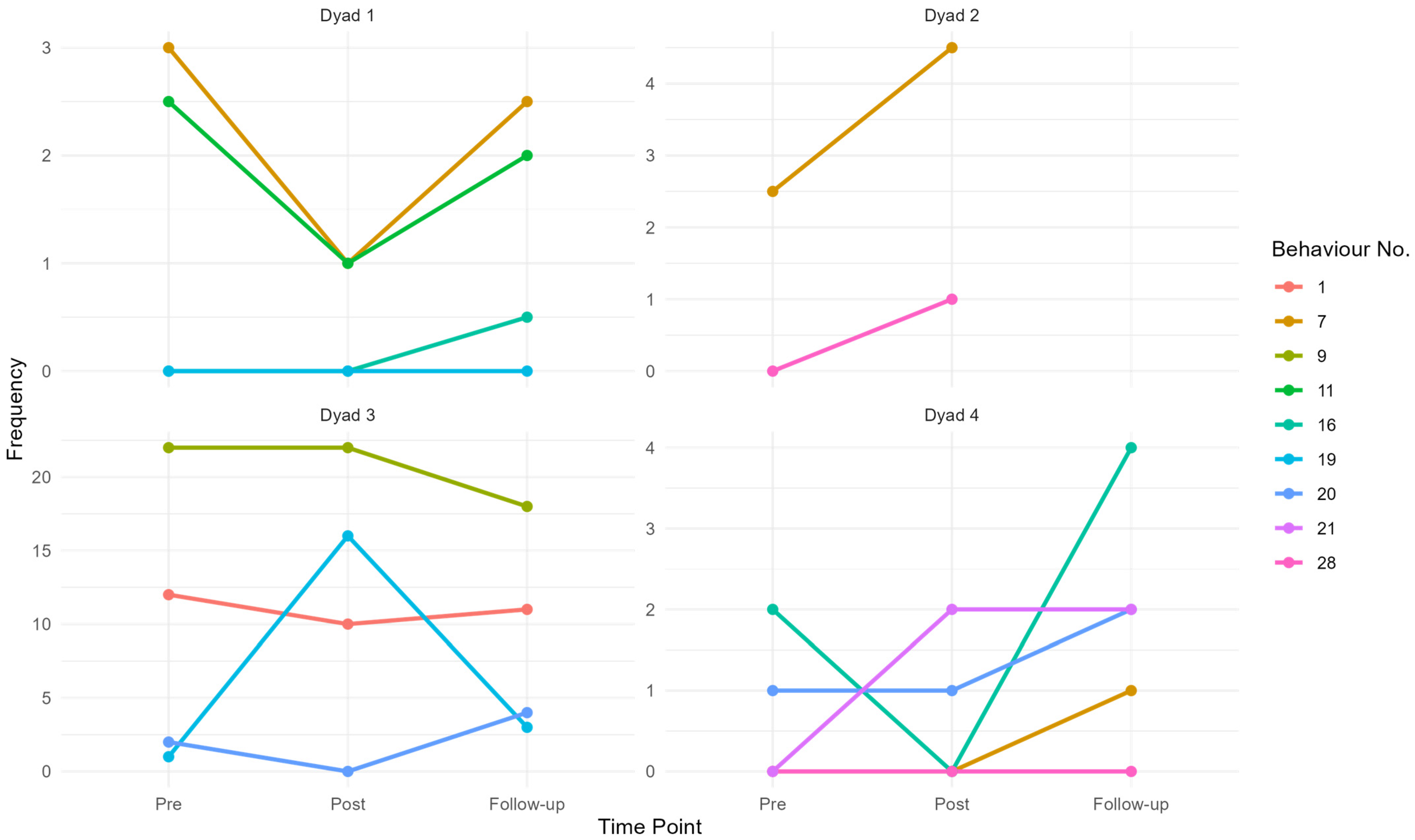

3.2.2. Conversation Behaviours

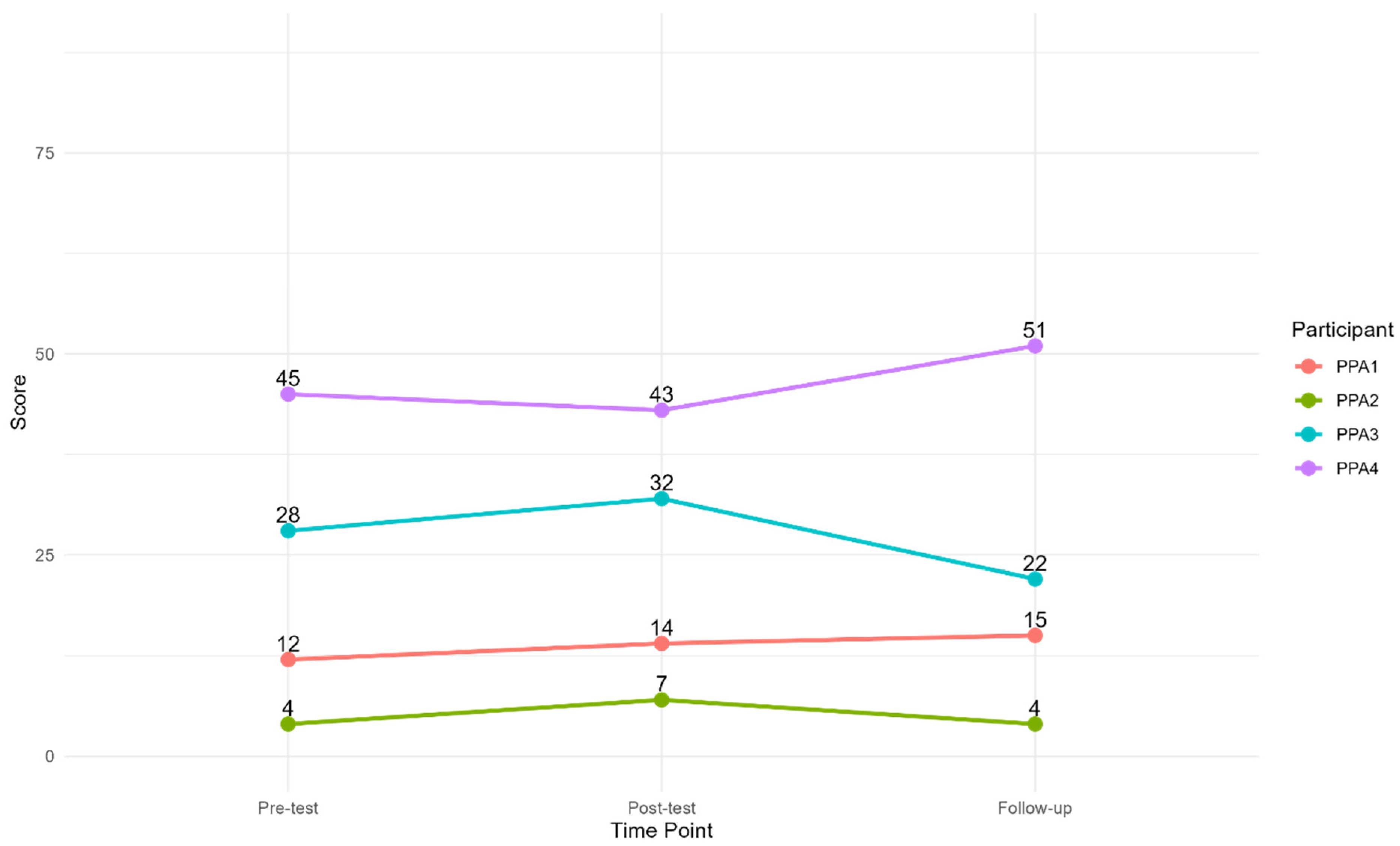

3.2.3. Functional Self-Rating Measure

4. Discussion

4.1. Fidelity to the Original BCPPA

4.2. Acceptability to Norwegian PwPPA and CPs

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPA | Primary progressive aphasia |

| PwPPA | People with primary progressive aphasia |

| CP | Communication partner |

| BCPPA | Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia |

| FTLD | Frontotemporal lobe degeneration |

| svPPA | Semantic variant PPA |

| nfvPPA | Non-fluent/agrammatic variant PPA |

| lvPPA | Logopenic variant PPA |

| CPT | Communication partner training |

| BCA | Better Conversations with Aphasia |

| UCL | University College London |

| SLT | Speech and language therapist |

| GAS | Goal Attainment Scaling |

| EBT | Evidence-based treatment |

| FRAME | Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications-Enhanced |

| CAT-N | Comprehensive Aphasia Test-Norwegian version |

| MMSE-NR3 | Mini-Mental State Examination-Norwegian Revised |

| AIQ-21 | Aphasia Impact Questionnaire-21 |

| CETI | Communicative Effectiveness Index |

Appendix A

| Process | Rationale | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptation/Modification | When? | Planned? | Who Decided? | What Modified? | Content Modification | Fidelity Consistent? | Goal of Modification | Recipient | Additional Comments |

| Translation from English to Norwegian | Pre-implementation/planning/pilot | Planned/Proactive adaption | Research team | Content | Tailoring/tweaking/refining | Fidelity consistent/core elements or functions preserved | Improve fit with recipient | First/spoken languages | |

| Session plan 1: the word “therapy” was translated to “samtaletrening” (conversation training) | Pre-implementation/planning/pilot | Planned/Proactive adaption | Research team | Content | Tailoring/tweaking/refining | Fidelity consistent/core elements or functions preserved | Improve fit with recipient | First/spoken languages | “Therapy” is not used in relation to speech and language therapy in Norwegian. Speech and language therapy = “logopedi”, speech and language therapist = “logoped”. |

| Session plan 1: “Therapy map” was translated to “BCPPA-mappen” (the BCPPA map). | Pre-implementation/planning/pilot | Planned/Proactive adaption | Research team | Content | Tailoring/tweaking/refining | Fidelity consistent/core elements or functions preserved | Improve fit with recipient | First/spoken languages | |

| Session plan 1: Added “this module is not available in Norwegian” when the session plan refers to video samples. | Pre-implementation/planning/pilot | Planned/Proactive adaption | Research team | Content | N/A | Fidelity consistent/core elements or functions preserved | N/A | ||

| Session plan 2: Added “This module is not available in Norwegian” when the session plan refers to Module 4 what to target in therapy | Pre-implementation/planning/pilot | Planned/Proactive adaption | Research team | Content | N/A | Fidelity consistent/core elements or functions preserved | N/A | ||

| Session plan 3: Added “This module is not available in Norwegian” when the session plan refers to Module 4 what to target in therapy | Pre-implementation/planning/pilot | Planned/Proactive adaption | Research team | Content | N/A | Fidelity consistent/core elements or functions preserved | N/A | ||

| Session plan 3: changed examples of sports (3e) and games (3k). | Pre-implementation/planning/pilot | Planned/Proactive adaption | Research team | Content | Tailoring/tweaking/refining | Fidelity consistent/core elements or functions preserved | Improve fit with recipients | First/spoken languages | Used common sports and games in Norway (e.g., handball instead of cricket). |

| Session plan 4: Information about where to seek help and more information about the diagnosis was changed to organisations and services in Norway. | Pre-implementation/planning/pilot | Planned/Proactive adaption | Research team | Content | Tailoring/tweaking/refining | Fidelity consistent/core elements or functions preserved | Improve fit with recipients | Access to resources | |

Appendix B. Core Component Checklist

| BCPPA CORE COMPONENT FIDELITY CHECKLIST: SESSION 1 What is Conversation? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Component Number | Component | Present |

| 1 | SLT provides an overview of BCPPA therapy | 1 |

| 2 | SLT introduces aims of current session | 1 |

| 3 | SLT facilitates a discussion with dyad about their current understanding of conversation to support their learning | 1 |

| 4 | SLT provides Module 5.0 Handout 1: How Does Conversation Work? | 1 |

| 5 | SLT explains how conversation works using Handout 1: How Does Conversation Work? | 1 |

| 6 | SLT facilitates a discussion with dyad about how conversation may be affected by PPA | 1 |

| 7 | SLT provides Module 5.0 Handout 2: What Can Go Wrong in Conversations? | 1 |

| 8 | SLT explains Module 5.0 Handout 2: What Can Go Wrong in Conversations? | 1 |

| Sum | 100 | |

| BCPPA CORE COMPONENT FIDELITY CHECKLIST: SESSION 2 Goal Setting | ||

|---|---|---|

| Component Number | Component | Present |

| 1 | SLT introduces aims of current session | 1 |

| 2 | SLT explains rationale for showing particular video clip | 1 |

| 3 | SLT shows dyad 2–3 pre-selected videos (30 s–2 min) | 1 |

| 4 | Each video clip is repeated 2–3 times (may not be applicable if they understood it the first time) | 1 |

| 5 | SLT ensures dyad has Handout 1: How does Conversation Work? provided in Session 1: What is Conversation? | 1 |

| 6 | SLT encourages CP and PwPPA to identify their own conversation facilitators in clip | 1 |

| 7 | SLT encourages CP and PwPPA to identify their own conversation barriers in clip | 1 |

| 8 | SLT provides Module 5.0 Handout 3: Goal Setting | 1 |

| 9 | SLT explains Module 5.0 Handout 3: Goal Setting | 1 |

| 10 | SLT supports PwPPA to identify their own therapy goals | 1 |

| 11 | SLT supports CP to identify their own therapy goals | 1 |

| 12 | Therapy goals were set for PwPPA | 1 |

| 13 | Therapy goals were set for CP | 1 |

| Sum | 100 | |

| BCPPA CORE COMPONENT FIDELITY CHECKLIST: SESSION 3 Practice | ||

|---|---|---|

| Component Number | Component | Present |

| 1 | SLT introduces aims of current session | 1 |

| 2 | SLT asks dyad to identify 1–2 conversation strategies to work on in the therapy session | 1 |

| 3 | SLT facilitates role-play task to practise target conversation strategies | 1 |

| 4 | SLT supports dyad to agree conversation topic for role play | 1 |

| 5 | SLT facilitates discussion with dyad to review conversation strategy/strategies practiced in role play tasks | |

| 6 | SLT supports dyad to identify contexts (times and place) to practise conversation strategy/strategies for home-based task | 1 |

| 7 | SLT supports dyad to discuss any concerns regarding practicing conversation strategy/strategies at home | 1 |

| Sum | 100 | |

| BCPPA CORE COMPONENT FIDELITY CHECKLIST: SESSION 4 Problem-Solving and Planning for the Future | ||

|---|---|---|

| Component Number | Component | Present |

| 1 | SLT introduces aims of current session | 1 |

| 2 | SLT supports dyad to agree conversation topic for role play | 1 |

| 3 | SLT facilitates role-play task to practise target conversation strategies | 1 |

| 4 | SLT facilitates discussion with dyad to review conversation strategy/strategies practiced in role play tasks | 1 |

| 5 | SLT ensures dyads has the Module 5.0 Handout 3: Goal Setting | 1 |

| 6 | SLT facilitates recap of the therapy goals set with CP and PwPPA in session 2 | 1 |

| 7 | SLT asks dyad to identify whether they have achieved their therapy goals | 1 |

| 8 | SLT facilitates discussion with dyad about considerations for managing changes in future communication | 1 |

| 9 | SLT provides Module 5.0 Handout 5: Information for the Future | 1 |

| 10 | SLT explains Module 5.0 Handout 5: Information for the Future and sign-posts dyad to resources for the future | 1 |

| Sum | 100 | |

Appendix C

- What do you think was most useful?

- What do you think should be changed?

- What do you think about the organisation of the intervention?

- Number of sessions?

- Duration of each session?

- Home-based tasks?

- Are there any changes to the wording or language we should make?

- The BCPPA was developed in the UK. Are there any changes we should make for it to work better in Norway?

- Are there any changes that should be made to make the therapy even more adapted to the Norwegian context?

Appendix D

| Dyad | Goals (Allocated to Either PwPPA or CP) | Achievement | Corresponding Behaviour No. and Description | Pre-Intervention Frequency | Post-Intervention Frequency | Follow-Up Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Give PwPPA time when she speaks (CP) | +1 | 7: CP lets the conversation continue, i.e., pauses for further clues/so PwPPA can use strategies. | 3 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Give myself enough time when speaking (PwPPA) | +1 | 16: CP asks “what do you want to talk about” or similar. | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | |

| Use gestures to describe a word when I cannot think of it (PwPPA) | +1 | 11: PwPPA talks around a word or concept when encounters word finding difficulties in a turn. | 2.5 | 1 | 2 | |

| Use objects when it is difficult to say the word (PwPPA) | 0 | 19: PwPPA uses gesture or mime in a turn when encountering a word finding difficulty. | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Do one thing at a time; avoid distractions during conversations with my partner (CP) | 0 | |||||

| 2 | Maintain what we got (PwPPA/CP) b | −1 | N/A | |||

| Give enough time in conversation to let the other person talk (PwPPA/CP) | 0 | 7: CP lets the conversation continue, i.e., pauses for further clues/so PwPPA can use strategies. | 2.5 | 4.5 | N/A | |

| Checking if we have understood each other correctly—clarifying what the other person means (PwPPA/CP) | 0 | 28: Understanding check-CP paraphrases the meaning of PwPPA’s prior turn as a means of checking what they have said. | 0 | 1 | N/A | |

| 3 | Express thoughts a (PwPPA) | −1 | 1: PwPPA responds with a substantive turn when asked a question. | 12 | 10 | 11 |

| 9: PwPPA initiates (verbal) turn. | 22 | 22 | 18 | |||

| PwPPA signals when he needs help finding a word a (PwPPA) | +1 | 19: PwPPA uses gesture or mime in a turn when encountering a word finding difficulty | 1 | 16 | 3 | |

| 20: PwPPA uses gesture or mime in a turn. | 2 | 0 | 4 | |||

| Talk on the phone: PwPPA answers when CP calls, and CP remembers to pause to give PwPPA time to talk (PwPPA/CP) b | +1 | N/A | ||||

| 4 | Be patient, understanding, and allowing time in conversations (CP) | +1 | 7: CP lets the conversation continue, i.e., pauses for further clues/so PwPPA can use strategies. | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 16: CP asks “what do you want to talk about” or similar. | 2 | 0 | 4 | |||

| Repeating what PwPPA said to check if CP has understood him correctly (CP) | +1 | 28: Understanding check-CP paraphrases the meaning of PwPPA’s prior turn as a means of checking what they have said. | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CP use gestures to make it easier for PwPPA to understand, and PwPPA use gestures to be understood a (PwPPA/CP) | −1 | 20: PwPPA uses gesture or mime in a turn. | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| 21 CP uses gesture in turn. | 0 | 2 | 2 |

References

- Marshall, C.R.; Hardy, C.J.D.; Volkmer, A.; Russell, L.L.; Bond, R.L.; Fletcher, P.D.; Clark, C.N.; Mummery, C.J.; Schott, J.M.; Rossor, M.N.; et al. Primary progressive aphasia: A clinical approach. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 1474–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyle-Gilchrist, I.T.S.; Dick, K.M.; Patterson, K.; Rodríquez, P.V.; Wehmann, E.; Wilcox, A.; Lansdall, C.J.; Dawson, K.E.; Wiggins, J.; Mead, S.; et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and survival of frontotemporal lobar degeneration syndromes. Neurology 2016, 86, 1736–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorno-Tempini, M.L.; Hillis, A.E.; Weintraub, S.; Kertesz, A.; Mendez, M.; Cappa, S.F.; Ogar, J.M.; Rohrer, J.D.; Black, S.; Boeve, B.F.; et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology 2011, 76, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K.; Howe, T.; Small, J.; Hsiung, G.-Y.R.; McCarron, E. The communication needs of people with primary progressive aphasia and their family: A scoping review. Aphasiology 2024, 38, 1484–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmer, A.; Alves, E.V.; Bar-Zeev, H.; Barbieri, E.; Battista, P.; Beales, A.; Beber, B.C.; Brotherhood, E.; Cadorio, I.R.; Carthery-Goulart, M.T.; et al. An international core outcome set for primary progressive aphasia (COS-PPA): Consensus-based recommendations for communication interventions across research and clinical settings. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 21, e14362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmer, A.; Alves, E.; Bar-Zeev, H.; Battista, P.; Brotherhood, E.V.; Cadorio, I.; Cartwright, J.; Farrington-Douglas, C.; Freitas, M.; Hendriksen, H.; et al. An international core outcome set for Primary Progressive Aphasia (COS-PPA): Commonalities in what people want to change about their lives with PPA across seventeen countries. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e14362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons-Mackie, N.P.; Raymer, A.P.; Cherney, L.R.P. Communication Partner Training in Aphasia: An Updated Systematic Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 2202–2221.e2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons-Mackie, N.P.; Raymer, A.P.; Armstrong, E.P.; Holland, A.P.; Cherney, L.R.P. Communication Partner Training in Aphasia: A Systematic Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 1814–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons-Mackie, N.N.; Damico, J.S. Reformulating the definition of compensatory strategies in aphasia. Aphasiology 1997, 11, 761–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmer, A.; Spector, A.; Meitanis, V.; Warren, J.D.; Beeke, S. Effects of functional communication interventions for people with primary progressive aphasia and their caregivers: A systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1381–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeke, S.; Sirman, N.; Beckley, F.; Maxim, J.; Edwards, S.; Swinburn, K.; Best, W.; Døli, H.; Erikstad, N.H.; Høeg, N.; et al. Better Conversations with Aphasia: An e-Learning Resource. Available online: https://extend.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=32§ion=4#tabs-tree-start (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Volkmer, A.; Spector, A.; Warren, J.D.; Beeke, S. The ‘Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia (BCPPA)’ program for people with PPA (Primary Progressive Aphasia): Protocol for a randomised controlled pilot study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018, 4, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmer, A.; Walton, H.; Swinburn, K.; Spector, A.; Warren, J.D.; Beeke, S. Results from a randomised controlled pilot study of the Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia (BCPPA) communication partner training program for people with PPA and their communication partners. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, S.; Laver, K.; Jeon, Y.-H.; Radford, K.; Low, L.-F. Frameworks for cultural adaptation of psychosocial interventions: A systematic review with narrative synthesis. Dementia 2023, 22, 1921–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, G.; Jiménez-Chafey, M.I.; Domenech Rodríguez, M.M. Cultural Adaptation of Treatments: A Resource for Considering Culture in Evidence-Based Practice. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Leino, A. Advancement in the maturing science of cultural adaptations of evidence-based interventions. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017, 85, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirman, S.W.; Miller, C.J.; Toder, K.; Calloway, A. Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltsey Stirman, S.; Baumann, A.A.; Miller, C.J. The FRAME: An expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksen, J.; Suzanne, B.; Analisa, P.; Evangelia-Antonia, E.; Apoorva, P.; Revkin, S.K.; Vandana, V.P.; Fabián, V.; Jasmina, V.; Jagoe, C. Communication partner training for healthcare workers engaging with people with aphasia: Enacting Sustainable Development Goal 17 in Austria, Egypt, Greece, India and Serbia. Int. J. Speech-Lang. Pathol. 2023, 25, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.J.; Marx, K.A.; Nkimbeng, M.; Johnson, E.; Koeuth, S.; Gaugler, J.E.; Gitlin, L.N. It’s More Than Language: Cultural Adaptation of a Proven Dementia Care Intervention for Hispanic/Latino Caregivers. Gerontologist 2022, 63, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Hepburn, K.; Haley, W.E.; Park, J.; Park, N.S.; Ko, L.K.; Kim, M.T. Examining cultural adaptations of the savvy caregiver program for Korean American caregivers using the framework for reporting adaptations and modifications-enhanced (FRAME). BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenson, C.; Harrell, S.P. Development and Testing of the 4-Domain Cultural Adaptation Model (CAM4). Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2021, 52, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmer, A.; Beeke, S.; Warren, J.D.; Spector, A.; Walton, H. Development of fidelity of delivery and enactment measures for interventions in communication disorders. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2024, 29, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindal, U. English in Norway. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of World Englishes; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Swinburn, K.; Porter, G.; Howard, D.; Høeg, N.; Norvik, M.; Røste, I.; Simonsen, H.G. CAT-N: Comprehensive Aphasia Test—Manual; Novus: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, C.; Engedal, K. Manual Norsk Revidert Mini Mental Status Evaluering (MMSE-NR3). Ageing and Health: Tønsberg, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, G.X.; Elder, J.P. Qualitative methods to ensure acceptability of behavioral and social interventions to the target population. J. Public Health Dent. 2011, 71 (Suppl. S1), S69–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner-Stokes, L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: A practical guide. Clin. Rehabil. 2009, 23, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwens, S.F.; van Heugten, C.M.; Verhey, F.R. The practical use of goal attainment scaling for people with acquired brain injury who receive cognitive rehabilitation. Clin. Rehabil. 2009, 23, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.; Jennie, P.; Bennett, P.C. The application of Goal Management Training to aspects of financial management in individuals with traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2012, 22, 852–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Better Conversations Downloads. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/brain-sciences/pals/research/language-and-cognition/language-and-cognition-research/better-conversations-lab/better-conversations-resources-and-downloads/better-conversations-downloads (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Lomas, J.; Pickard, L.; Bester, S.; Erlbard, H.; Finlayson, A.; Zoghaib, C.; Haaland-Johansen, L.; Hammersvik, L.; Lind, M. Spørreskjema for Nærpersoner Communicative Effectiveness Index (CETI) på Norsk Manual. 2006. Available online: https://www.statped.no/ressurser-og-verktoy/ressurser/ceti-sporreskjema-for-naerpersoner/ (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, W.; Maxim, J.; Heilemann, C.; Beckley, F.; Johnson, F.; Edwards, S.I.; Howard, D.; Beeke, S. Conversation Therapy with People with Aphasia and Conversation Partners using Video Feedback: A Group and Case Series Investigation of Changes in Interaction. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Norway. Educational Attainment of the Population. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/utdanningsniva/statistikk/befolkningens-utdanningsniva (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Lomas, J.; Pickard, L.; Bester, S.; Elbard, H.; Finlayson, A.; Zoghaib, C. The communicative effectiveness index: Development and psychometric evaluation of a functional communication measure for adult aphasia. J. Speech Hear. Disord. 1989, 54, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T.M.; Mukadam, N.P.; Sommerlad, A.P.; Guerra Ceballos, S.M.; Livingston, G.P. Culturally tailored therapeutic interventions for people affected by dementia: A systematic review and new conceptual model. Lancet. Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e171–e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizidou, M.; Brotherhood, E.; Harding, E.; Crutch, S.; Warren, J.D.; Hardy, C.J.; Volkmer, A. ‘Like going into a chocolate shop, blindfolded’: What do people with primary progressive aphasia want from speech and language therapy? Int. J. Lang. Commun. Disord. 2023, 58, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.; Ponsford, J. Goal Attainment Scaling in brain injury rehabilitation: Strengths, limitations and recommendations for future applications. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2014, 24, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegter, O.; Santos, H.; Rademaker, A.W.; Roberts, A.C.; Rogalski, E. Suitability of Goal Attainment Scaling in Older Adult Populations with Neurodegenerative Disease Experiencing Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gerontology 2023, 69, 1002–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulugut, H.; Stek, S.; Wagemans, L.E.E.; Jutten, R.J.; Keulen, M.A.; Bouwman, F.H.; Prins, N.D.; Lemstra, A.W.; Krudop, W.; Teunissen, C.E.; et al. The natural history of primary progressive aphasia: Beyond aphasia. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmer, A.; Cartwright, J.; Ruggero, L.; Beales, A.; Gallée, J.; Grasso, S.; Henry, M.; Jokel, R.; Kindell, J.; Khayum, R.; et al. Principles and philosophies for speech and language therapists working with people with primary progressive aphasia: An international expert consensus. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peto, V.; Jenkinson, C.; Fitzpatrick, R. Determining minimally important differences for the PDQ-39 Parkinson’s disease questionnaire. Age Ageing 2001, 30, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Session | Aims | Adaptations at a Glance |

|---|---|---|

| What is conversation? | Discuss the aims of therapy. Discuss and explore what conversation is and how it can go wrong. Initial viewing of their own conversation video. | Added an explanation in the session plan about an e-learning module that is not available in Norwegian. |

| Goal setting | Identify barriers and facilitators in their own conversation. Set goals for therapy based on this discussion. | Added an explanation in the session plan about an e-learning module that is not available in Norwegian. |

| Practice | Practice conversation using the strategies identified during goal-setting. Problem-solve any issues that have arisen in using identified strategies in conversations outside of therapy sessions. | Added an explanation in the session plan about an e-learning module that is not available in Norwegian. Changed some of the examples of conversation topics in the session plan. |

| Problem-solving and planning for the future | Practice conversation using the strategies identified during goal-setting. Consider planning for future changes in communication. | Changed information in the session plan about where to seek help and find more information about the diagnosis. |

| Respondent | Measure | Rationale | Time Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| PwPPA | CAT-N | Overview of language function | Pre-intervention |

| PwPPA | MMSE-NR3 | Overview of cognitive function | Pre-intervention |

| PwPPA | Aphasia Impact Questionnaire-21 | Measure the impact of the PPA as perceived by the person with PPA. | Pre- and post-intervention, and at 3-month follow-up |

| CP | Communicative Effectiveness Index | Measure changes in functional communication as perceived by a CP. | Pre- and post-intervention, and at 3-month follow-up |

| Dyad | Goal Attainment Scaling | To individualise targets for intervention and measure change as rated by the dyads. | During intervention |

| 10-min video recordings | Measure change in communication behaviour targeted in treatment. | Pre- and post-intervention, and at 3-month follow-up |

| Meaning Unit | Condensed Meaning Unit | Code | Category | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Because you are there and kind of holding the space for us to confront those kinds of painful realities and to think about how we well kind of address it more directly and how we can handle the communication and stuff like that” | A space to confront the realities | Address realities | BCPPA as something different | BCPPA provides a different perspective |

| Dyad | Pre-Testing | Post-Testing | Follow-Up | Video Clips from Each Time Point Used in the Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PPA1 | PPA2 | PPA3 | PPA4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 80 | 80 | 77 | 55 |

| Biological sex | Female | Female | Male | Male |

| Diagnosis at the time of inclusion | Mixed | Mixed | nfvPPA | nfvPPA |

| Education (years) | 18 | 13 | 14 | 18 |

| Time post diagnosis (years) | <1 | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| First language | Norwegian | Norwegian | Norwegian | Norwegian |

| MMSE-NR3 | ||||

| Orientation (10) | 6 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| Immediate recall (3) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Calculation (5) | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| Delayed recall (3) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Language and praxis (8) | 5 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Figure copying (1) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total MMSE Score (total possible score = 30) | 21 | 24 | 28 | 28 |

| CAT-N | ||||

| Auditory comprehension (66) | 62 | 64 | 59 | 59 |

| Reading comprehension (62) | 57 | 53 | 52 | 56 |

| Repetition (74) | 66 | 66 | 59 | 53 |

| Naming (79) | 28 | 71 | 63 | 57 |

| Oral reading (70) | 70 | 69 | 70 | 70 |

| Communication partner | ||||

| CP1 | CP2 | CP3 | CP4 | |

| Relationship to person with PPA | Husband | Husband | Wife | Wife |

| First language | Norwegian | German | Norwegian | English |

| Timepoint | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 22.25 | 20 | 18.15 |

| Post | 24 | 23 | 16.47 |

| Follow-up | 23 | 18.5 | 20.08 |

| Timepoint | Mean | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 60.91 | 55.89 | 23.08 |

| Post | 64.98 | 60.33 | 14.5 |

| Follow-up | 64.3 | 59.86 | 20.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Winsnes, I.; Norvik, M.; Volkmer, A. Adaptation of Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia to Norwegian. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090994

Winsnes I, Norvik M, Volkmer A. Adaptation of Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia to Norwegian. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(9):994. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090994

Chicago/Turabian StyleWinsnes, Ingvild, Monica Norvik, and Anna Volkmer. 2025. "Adaptation of Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia to Norwegian" Brain Sciences 15, no. 9: 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090994

APA StyleWinsnes, I., Norvik, M., & Volkmer, A. (2025). Adaptation of Better Conversations with Primary Progressive Aphasia to Norwegian. Brain Sciences, 15(9), 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090994