The Relationship Between Camouflaging and Lifetime Depression Among Adult Autistic Males and Females

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Camouflaging in Autism

1.2. Impact of Camouflaging on Mental Wellbeing

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

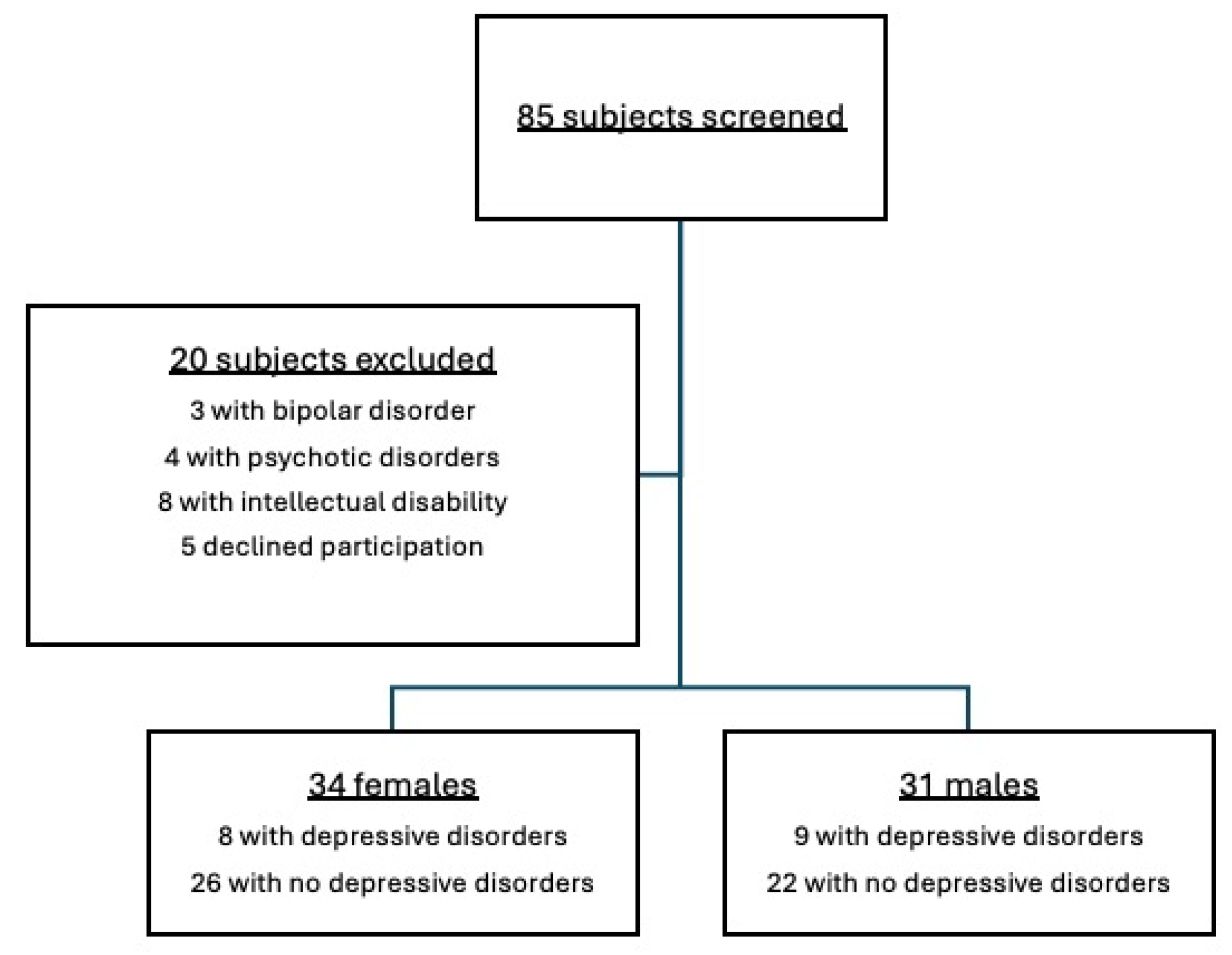

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Assessment of Depression

2.4. Assessment of Autism

2.5. Assessment of Camouflaging

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.6.1. Research Question 1: Do Autistic Females and Males Seeking Treatment for Concurrent Mental Disorders Display Different Levels of Camouflaging?

2.6.2. Research Question 2: Is Camouflaging Associated with Specific Dimensions of Autism, and Does Sex Play a Role in These Associations?

2.6.3. Research Question 3: Is Camouflaging Associated with Depressive Disorders, and Does Sex Matter in This Association?

3. Results

3.1. Do Autistic Females and Males Seeking Treatment for Psychiatric Comorbidities Display Different Levels of Camouflaging?

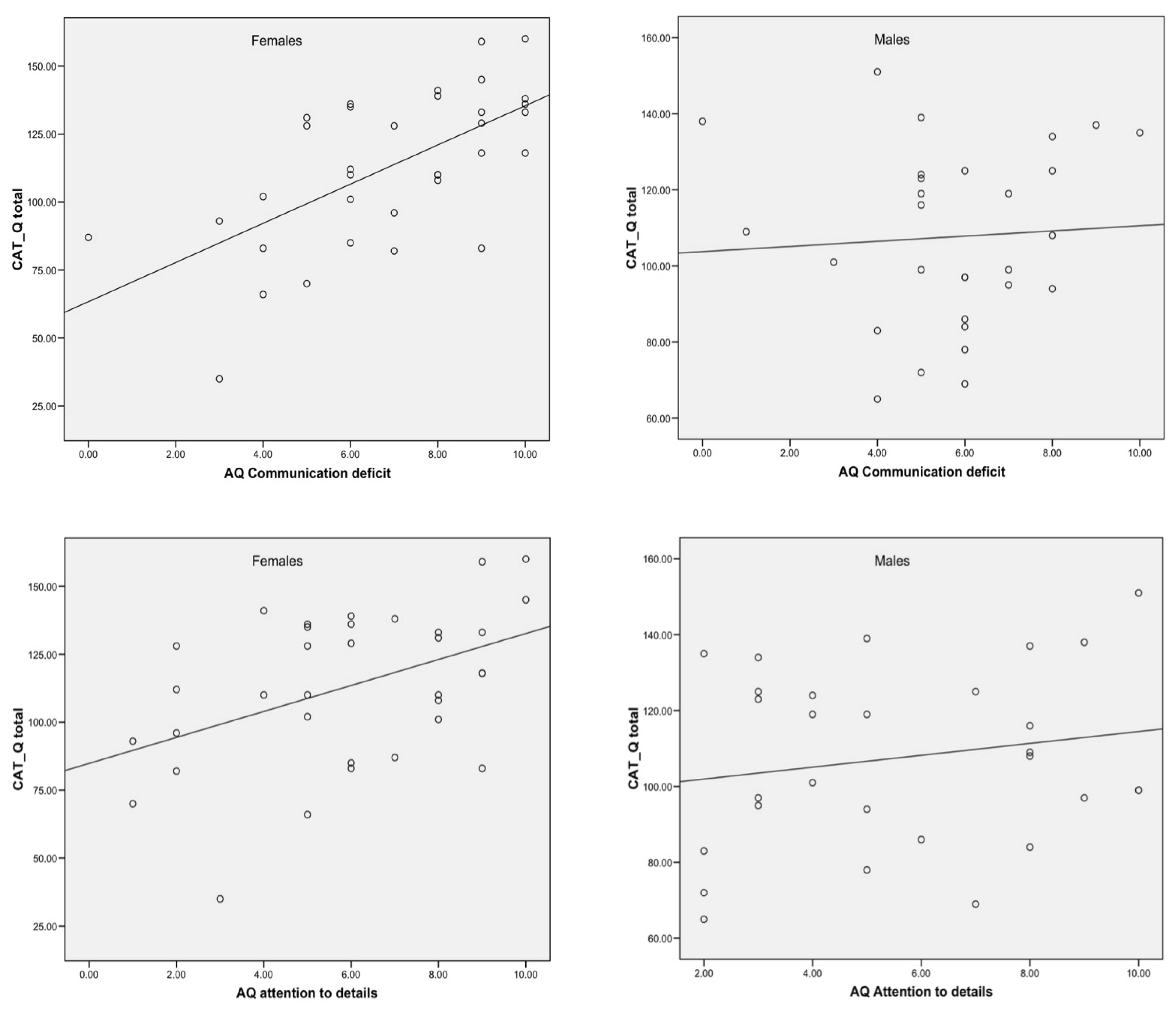

3.2. Is Camouflaging Associated with Specific ASD Dimensions? Does Sex Play a Role in These Associations?

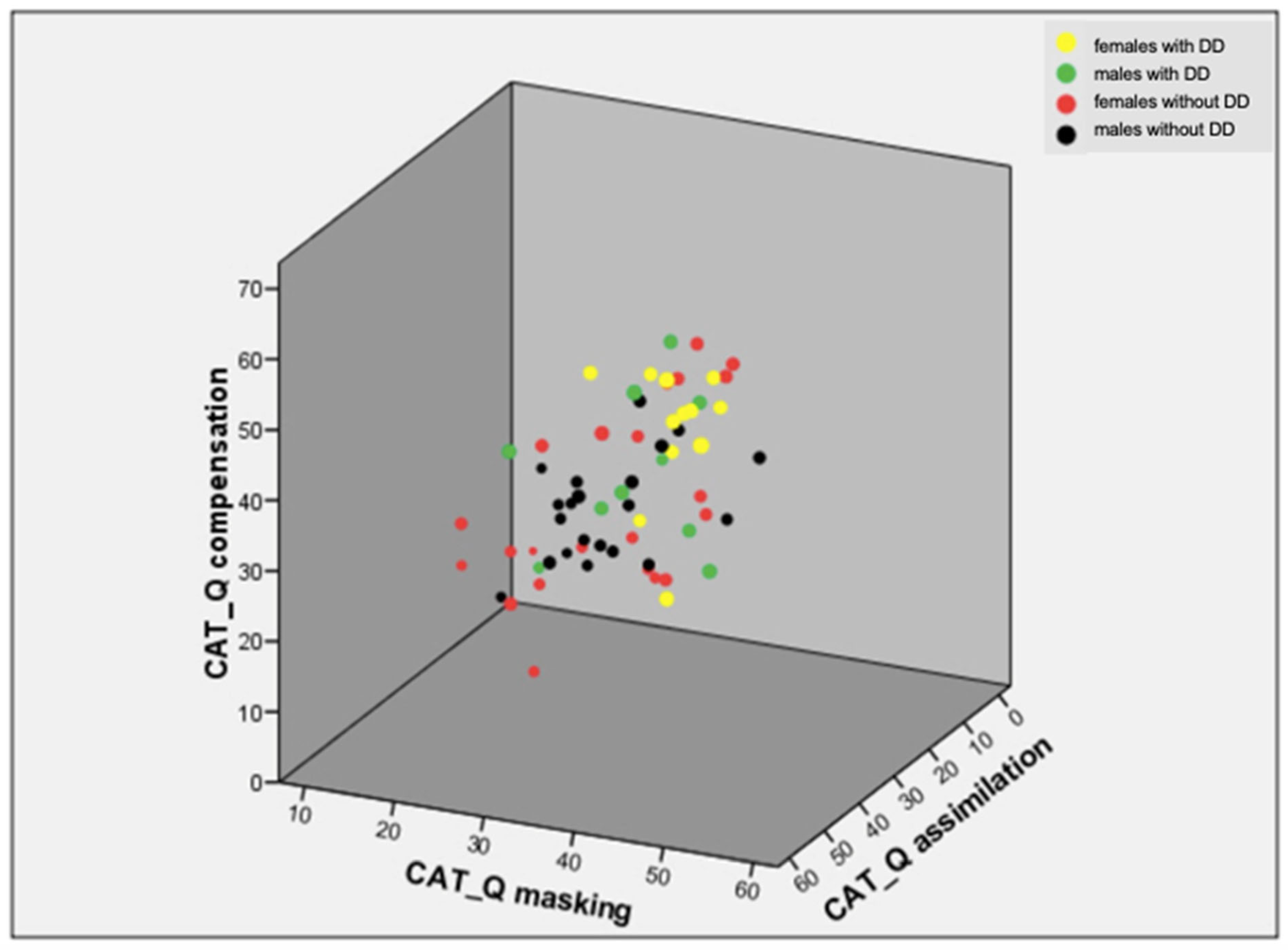

3.3. Is Camouflaging Associated with Lifetime Diagnosis of Depressive Disorders? Does Sex Matter in This Association?

4. Discussion

4.1. Levels of Camouflaging Across Sexes

4.2. Associations Between Camouflaging and Autism Dimensions, and the Role of Sex

4.3. Relationship Between Camouflaging and Lifetime Diagnosis of Depressive Disorders, and the Role of Sex

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AQ | Autism Spectrum Quotient |

| CAT-Q | Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire |

| IQ | Intelligence Quotient |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M.; Song, M.; Yon, D.K.; Lee, S.W.; Fombonne, E.; Kim, M.S.; Park, S.; Lee, M.H.; Hwang, J.; Keller, R.; et al. Incidence, Prevalence, and Global Burden of Autism Spectrum Disorder from 1990 to 2019 across 204 Countries. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 4172–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.-C.; Lombardo, M.V.; Ruigrok, A.N.; Chakrabarti, B.; Auyeung, B.; Szatmari, P.; Happé, F.; Baron-Cohen, S.; MRC AIMS Consortium. Quantifying and Exploring Camouflaging in Men and Women with Autism. Autism 2017, 21, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturrock, A.; Adams, C.; Freed, J. A Subtle Profile with a Significant Impact: Language and Communication Difficulties for Autistic Females Without Intellectual Disability. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 621742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D.M.; Warrier, V.; Abu-Akel, A.; Allison, C.; Gajos, K.Z.; Reinecke, K.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Radecki, M.A.; Baron-Cohen, S. Sex and Age Differences in “Theory of Mind” across 57 Countries Using the English Version of the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2022385119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargiela, S.; Steward, R.; Mandy, W. The Experiences of Late-Diagnosed Women with Autism Spectrum Conditions: An Investigation of the Female Autism Phenotype. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 3281–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnhardt, F.-G.; Falter, C.M.; Gawronski, A.; Pfeiffer, K.; Tepest, R.; Franklin, J.; Vogeley, K. Sex-Related Cognitive Profile in Autism Spectrum Disorders Diagnosed Late in Life: Implications for the Female Autistic Phenotype. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.-C.; Baron-Cohen, S. Identifying the Lost Generation of Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 1013–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, L.; Petrides, K.V.; Allison, C.; Smith, P.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Lai, M.-C.; Mandy, W. “Putting on My Best Normal”: Social Camouflaging in Adults with Autism Spectrum Conditions. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017, 47, 2519–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwood, T. The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK; Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, L.; Shaw, R.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Cassidy, S. Autistic Adults’ Experiences of Camouflaging and Its Perceived Impact on Mental Health. Autism Adulthood 2021, 3, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Hull, L.; Petrides, K.V. Big Five Model and Trait Emotional Intelligence in Camouflaging Behaviours in Autism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2020, 152, 109565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, L.; Levy, L.; Lai, M.-C.; Petrides, K.V.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Allison, C.; Smith, P.; Mandy, W. Is Social Camouflaging Associated with Anxiety and Depression in Autistic Adults? Mol. Autism 2021, 12, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cage, E.; Di Monaco, J.; Newell, V. Experiences of Autism Acceptance and Mental Health in Autistic Adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cage, E.; Troxell-Whitman, Z. Understanding the Reasons, Contexts and Costs of Camouflaging for Autistic Adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 1899–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, F.; Takahashi, T.; Tamura, M.; Guan, S.; Seto, M.; Hull, L.; Mandy, W.; Tsuchiya, K.; Shimizu, E. The Association between Social Camouflage and Mental Health among Autistic People in Japan and the UK: A Cross-Cultural Study. Mol. Autism 2024, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, L.; Ruta, L.; Reale, L. Psychiatric comorbidities in asperger syndrome and high functioning autism: Diagnostic challenges. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, S.; Tan, D.W.; Reddrop, S.; Dean, L.; Maybery, M.; Magiati, I. Psychosocial factors associated with camouflaging in autistic people and its relationship with mental health and well-being: A mixed methods systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 105, 102335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 2010th ed.; 10th Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.B.; Williams, J.B.W.; Karg, R.S.; Spitzer, R.L. SCID-5-CV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders—Clinician Version; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S. The Empathy Quotient: An Investigation of Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism, and Normal Sex Differences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, H.; Eisler, I.; Mandy, W.; Leppanen, J.; Treasure, J.; Tchanturia, K. Using the Autism-Spectrum Quotient to Measure Autistic Traits in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leth-Steensen, C.; Gallitto, E.; Mintah, K.; Parlow, S.E. Testing the Latent Structure of the Autism Spectrum Quotient in a Sub-Clinical Sample of University Students Using Factor Mixture Modelling. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2021, 51, 3722–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundin Remnélius, K.; Bölte, S. Camouflaging in Autism: Age Effects and Cross-Cultural Validation of the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2024, 54, 1749–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Osso, L.; Cremone, I.M.; Muti, D.; Massimetti, G.; Lorenzi, P.; Carmassi, C.; Carpita, B. Validation of the Italian Version of the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) in a University Population. Compr. Psychiatry 2022, 114, 152295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Business Machines Corporation. SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 26.0; International Business Machines Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid, G.A.; Lee, N.R.; Wallace, G.L. Camouflaging in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Examining the Roles of Sex, Gender Identity, and Diagnostic Timing. Autism 2022, 26, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.; Zubizarreta, S.C.-P.; Costa, A.D.; Araújo, R.; Martinho, J.; Tubío-Fungueiriño, M.; Sampaio, A.; Cruz, R.; Carracedo, A.; Fernández-Prieto, M. Is There a Bias Towards Males in the Diagnosis of Autism? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2025, 35, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, A.M.; McGillivray, J.A.; Stokes, M.A. Gender Differences in Emotionality and Sociability in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Mol. Autism 2014, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgewick, F.; Hill, V.; Yates, R.; Pickering, L.; Pellicano, E. Gender Differences in the Social Motivation and Friendship Experiences of Autistic and Non-Autistic Adolescents. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2016, 46, 1297–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.-C.; Lombardo, M.V.; Pasco, G.; Ruigrok, A.N.V.; Wheelwright, S.J.; Sadek, S.A.; Chakrabarti, B.; MRC AIMS Consortium; Baron-Cohen, S. A Behavioral Comparison of Male and Female Adults with High Functioning Autism Spectrum Conditions. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.-C.; Lombardo, M.V.; Ruigrok, A.N.V.; Chakrabarti, B.; Wheelwright, S.J.; Auyeung, B.; Allison, C.; MRC AIMS Consortium; Baron-Cohen, S. Cognition in Males and Females with Autism: Similarities and Differences. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| p | Chi-Squared | Males | Females (n = 34) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 31) | ||||

| Education | ||||

| 0.173 | 4.98 | 4 (12.9) | 8 (23.5) | Elementary |

| 17 (54.8) | 19 (55.9) | Medium | ||

| 10 (32.3) | 5 (14.7) | High school | ||

| 0 (0) | 2 (5.9) | Laurea degree | ||

| Employment Status | ||||

| 0.59 | 0.291 | 22 (71.0) | 22 (64.7) | Employed |

| 9 (29.0) | 12 (35.3) | Unemployed | ||

| Marital Status | ||||

| 0.11 | 2.55 | 30 (96.8) | 29 (85.3) | Single |

| 1 (3.2) | 5 (14.7) | In a relationship | ||

| p | t | |||

| 0.589 | 0.544 | 27.5 (7.6) | 28.8 (11.5) | Age |

| 0.302 | 1.041 | 106.2 (23.3) | 112.9 (28.2) | CAT-Q total |

| 0.255 | 1.149 | 35.8 (10.8) | 39.5 (14.9) | Compensation |

| 0.337 | 0.968 | 34.2 (8.0) | 36.4 (9.5) | Camouflage |

| 0.703 | 0.383 | 36.2 (9.2) | 37.1 (9.6) | Assimilation |

| 0.05 | 2.002 | 28.6 (7.4) | 32.6 (8.1) | AQ total |

| 0.108 | 1.631 | 5.7 (2.7) | 6.8 (2.7) | Social skills |

| 0.008 | 2.739 | 6.9 (1.6) | 8.1 (1.8) | Attention switching |

| 0.047 | 2.029 | 5.7 (2.2) | 6.9 (2.5) | Communication deficit |

| 0.703 | 0.384 | 5.6 (2.7) | 5.9 (2.7) | Attention to details |

| 0.753 | 0.93 | 4.7 (2.1) | 4.9 (2.0) | Imagination |

| AQ | AQ | AQ | AQ | AQ | AQ | CAT-Q ass | CAT-Q cam | CAT-Q com | CAT-Q Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | I | C | AS | SS | Total | |||||

| CAT-Q total | ||||||||||

| 0.894 ** | CAT-Q com | |||||||||

| 0.685 ** | 0.843 ** | CAT-Q cam | ||||||||

| 0.434 ** | 0.428 ** | 0.724 ** | CAT-Q ass | |||||||

| 0.474 ** | 0.157 | 0.329 ** | 0.392 ** | AQ total | ||||||

| 0.803 ** | 0.428 ** | −0.035 | 0.08 | 0.184 | AQ SS | |||||

| 0.590 ** | 0.700 ** | 0.300 * | 0.147 | 0.268 * | 0.295 * | AQ AS | ||||

| 0.508 ** | 0.628 ** | 0.800 ** | 0.465 ** | 0.213 | 0.357 ** | 0.423 ** | AQ C | |||

| 0.366 ** | 0.324 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.651 ** | 0.308 * | −0.105 | 0.01 | 0.081 | AQ I | ||

| 0.136 | 0.227 | 0.097 | 0.038 | 0.474 ** | 0.123 | 0.290 * | 0.387 ** | 0.340 ** | AQ AD |

| Nagelkerke R2 = 0.358 | Cox R2 = 0.251 | p | CI 95% | B (SE) | |

| 0.2 | 0.879–1.027 | −051 (0.040) | Age | ||

| 0.003 | 1.018–1.093 | −0.053 (0.018) | CAT-Q total | ||

| 0.458 | 0.943–1.140 | 0.036 (0.048) | AQ total | ||

| 0.807 | 0.207–3.409 | −0.174 (0.715) | Sex [male] |

| p | t | Non-DD | DD | p | F | F with DD | M with DD | F with No DD | M with No DD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 45 | n = 20 | |||||||||

| <0.001 | −4.42 | 101.4 (24.4) | 128.6 (18.9) | <0.001 * | 10.66 | 134.8 (16.1) | 125.2 (22.1) | 101.0 (26.3) | 97.2 (18.1) | CAT-Q total |

| 0.002 | −3.24 | 34.4 (13.0) | 45.2 (10.5) | <0.001 * | 6.96 | 49.4 (9.6) | 43.1 (11.9) | 34.1 (14.7) | 32.3 (8.5) | CAT-Q com |

| 0.001 | −3.67 | 32.9 88.6) | 40.9 (6.8) | 0.001 * | 6.38 | 42.9 (4.9) | 38.9 (7.8) | 32.8 (9.6) | 32.0 (7.3) | CAT-Q cam |

| <0.001 | −3.71 | 34.0 (8.5) | 42.6 (8.5) | <0.001 § | 5.95 | 42.4 (7.6) | 43.2 (9.7) | 34.2 (9.4) | 32.9 (7.0) | CAT-Q ass |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gesi, C.; Pisani, R.; Tamburini, N.; Dell’Osso, B. The Relationship Between Camouflaging and Lifetime Depression Among Adult Autistic Males and Females. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 920. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090920

Gesi C, Pisani R, Tamburini N, Dell’Osso B. The Relationship Between Camouflaging and Lifetime Depression Among Adult Autistic Males and Females. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(9):920. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090920

Chicago/Turabian StyleGesi, Camilla, Roberta Pisani, Nicolò Tamburini, and Bernardo Dell’Osso. 2025. "The Relationship Between Camouflaging and Lifetime Depression Among Adult Autistic Males and Females" Brain Sciences 15, no. 9: 920. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090920

APA StyleGesi, C., Pisani, R., Tamburini, N., & Dell’Osso, B. (2025). The Relationship Between Camouflaging and Lifetime Depression Among Adult Autistic Males and Females. Brain Sciences, 15(9), 920. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090920