The Involvement of Thalamic Nuclei in Schizophrenia Patients with and Without Auditory Verbal Hallucinations: A Brain Morphometry Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

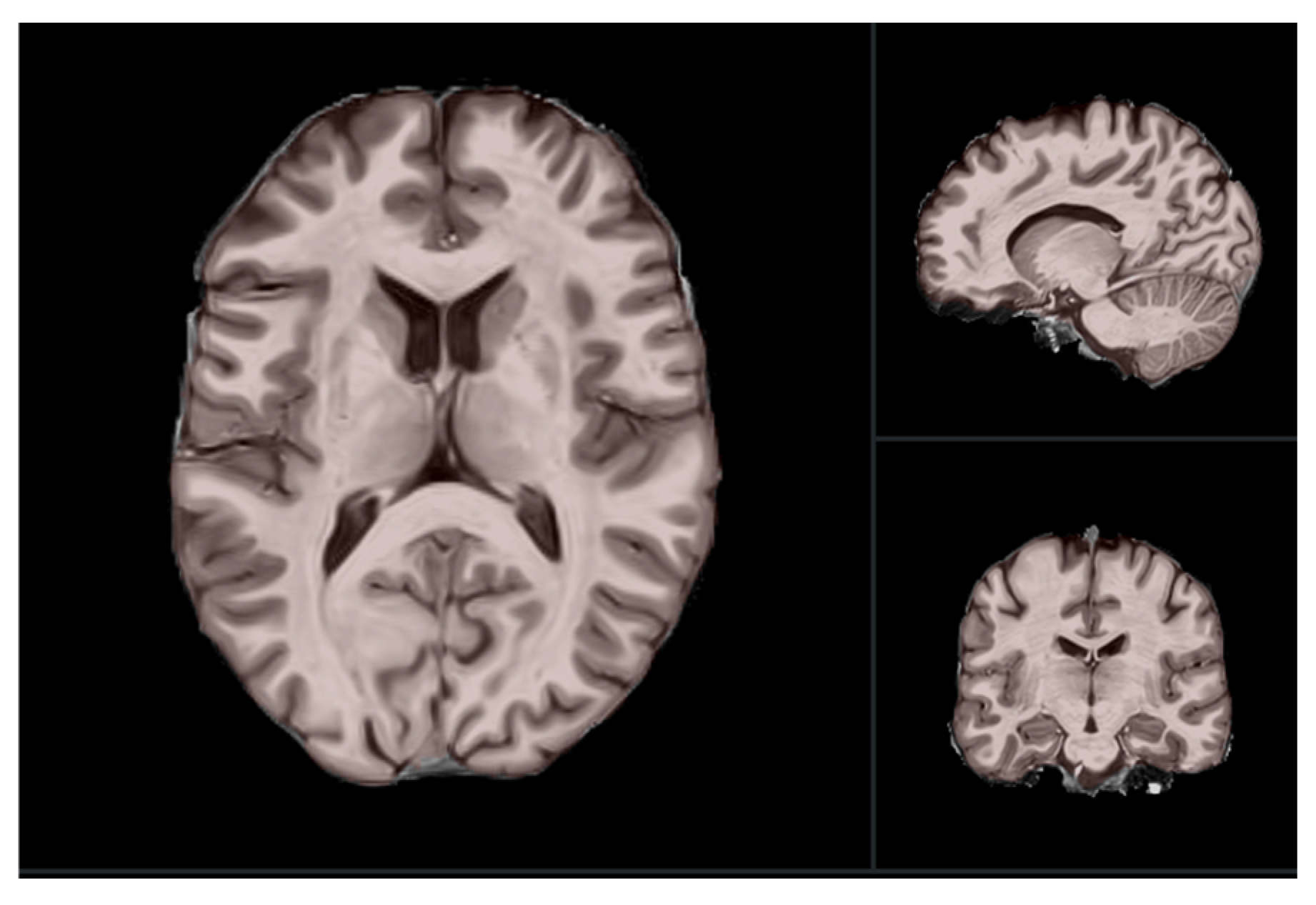

2.2. MRI Data Acquisition

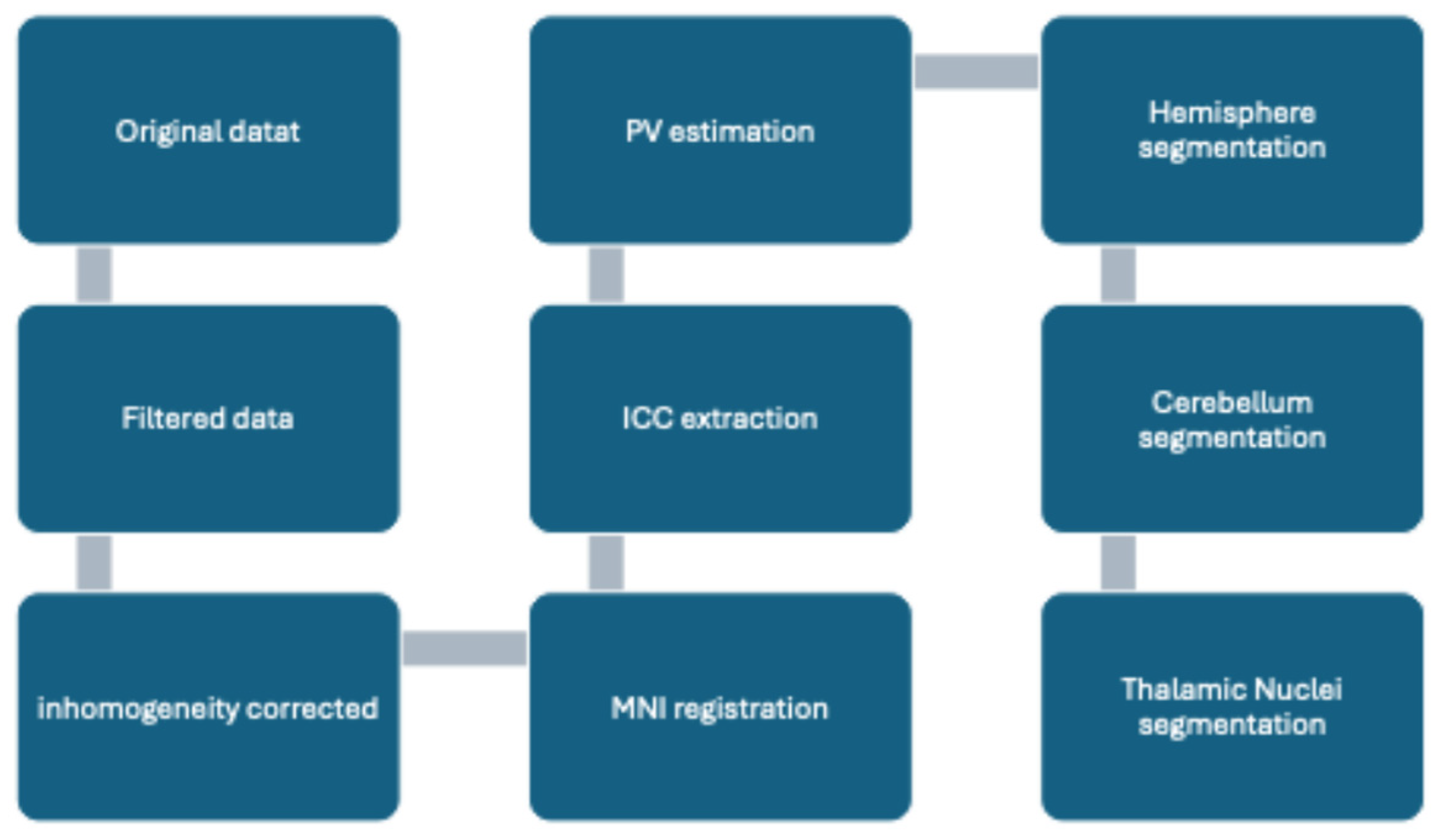

2.3. Pre-Processing Methods

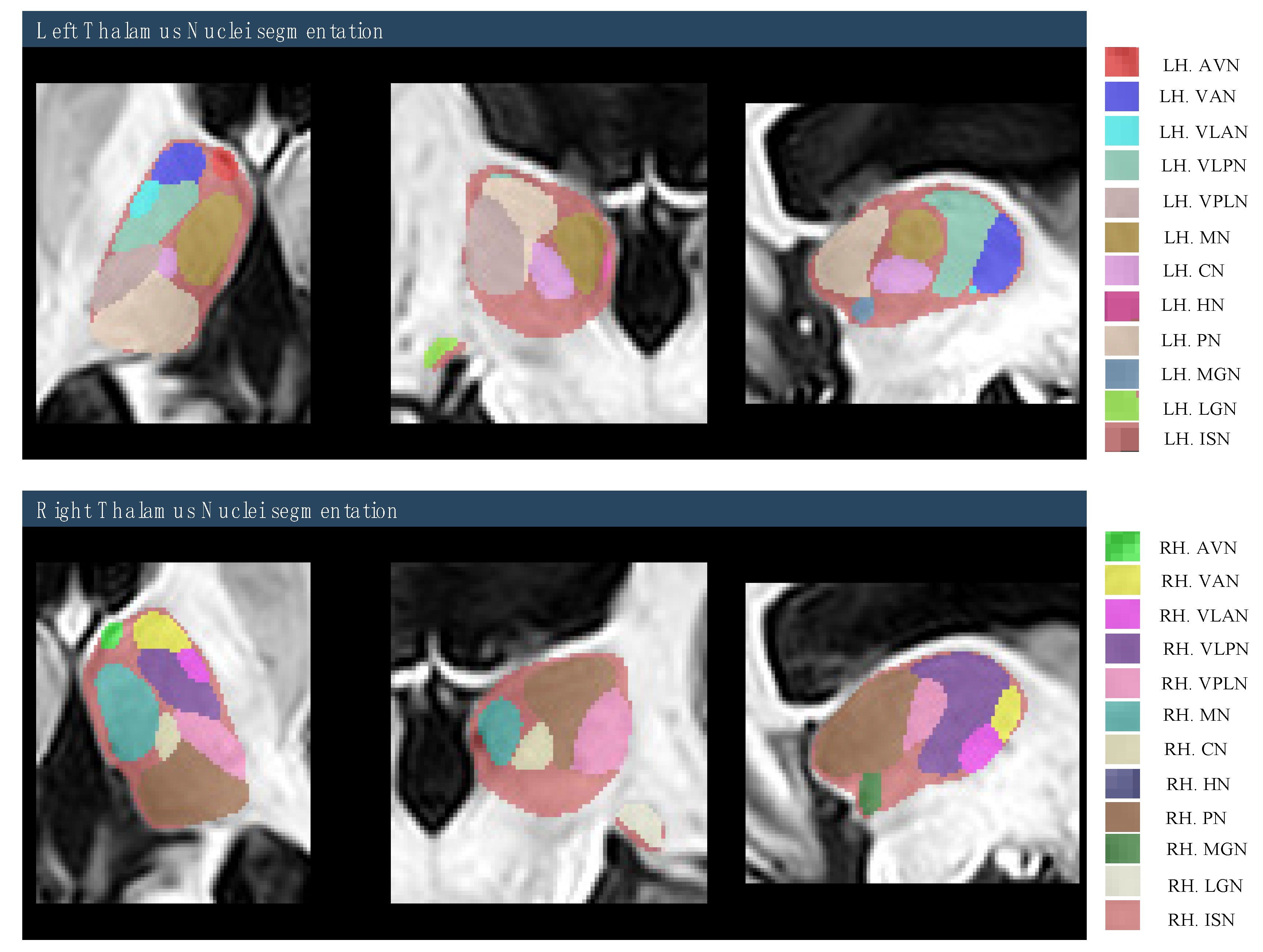

2.4. Region of Interest (ROI) Selection

2.5. Quality Control Procedure

2.6. ICV Normalization Methods

2.7. Hemispheric Asymmetries Measurements

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Comparison of ICVs Between Study Groups

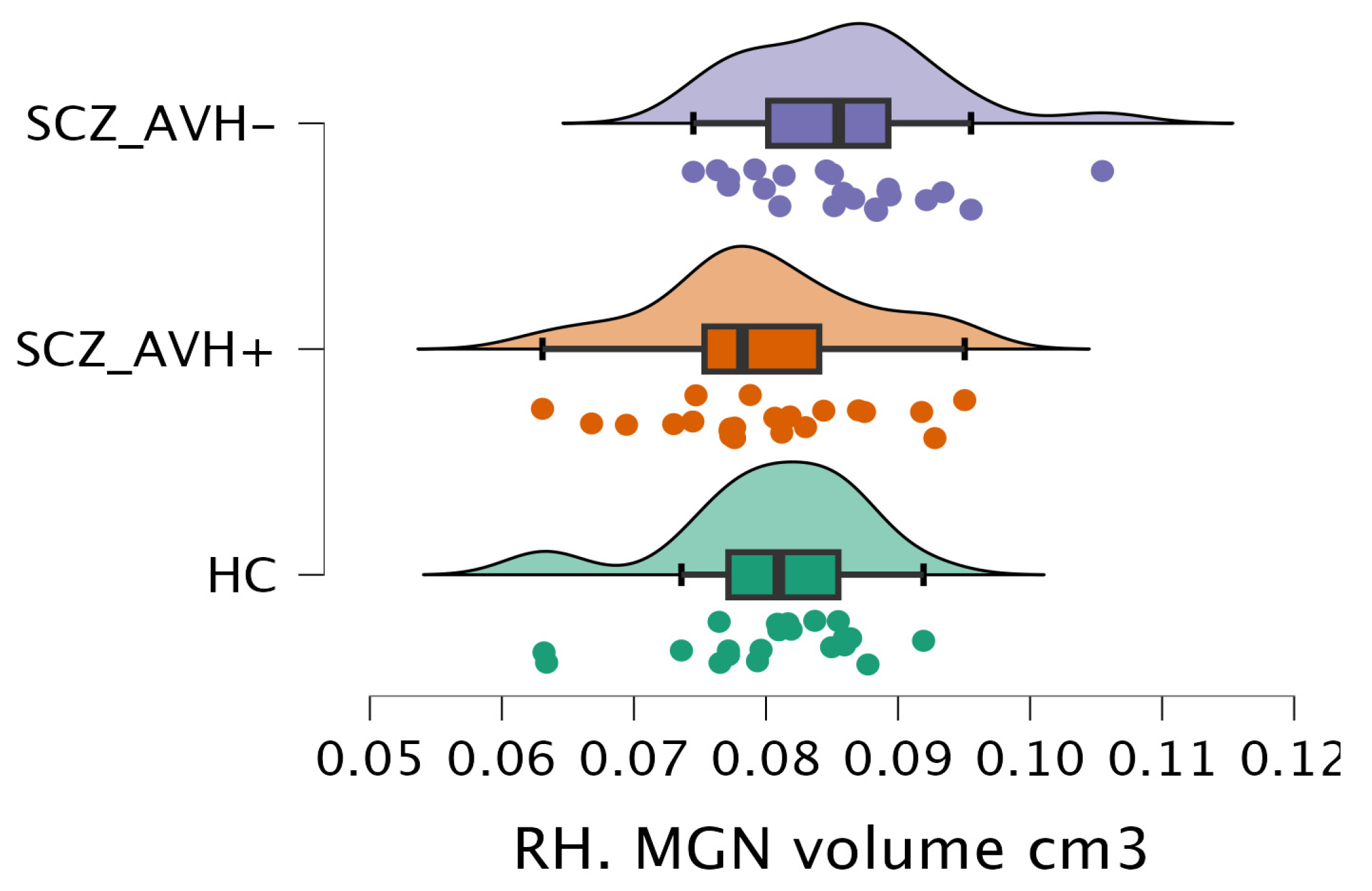

3.3. Comparison of Volumetric Measurements of Thalamus Nuclei Segmentation Between Study Groups

3.4. Comparison of Hemispheric Laterality of Thalamus and Thalamic Nuclei Volumes Between Study Groups

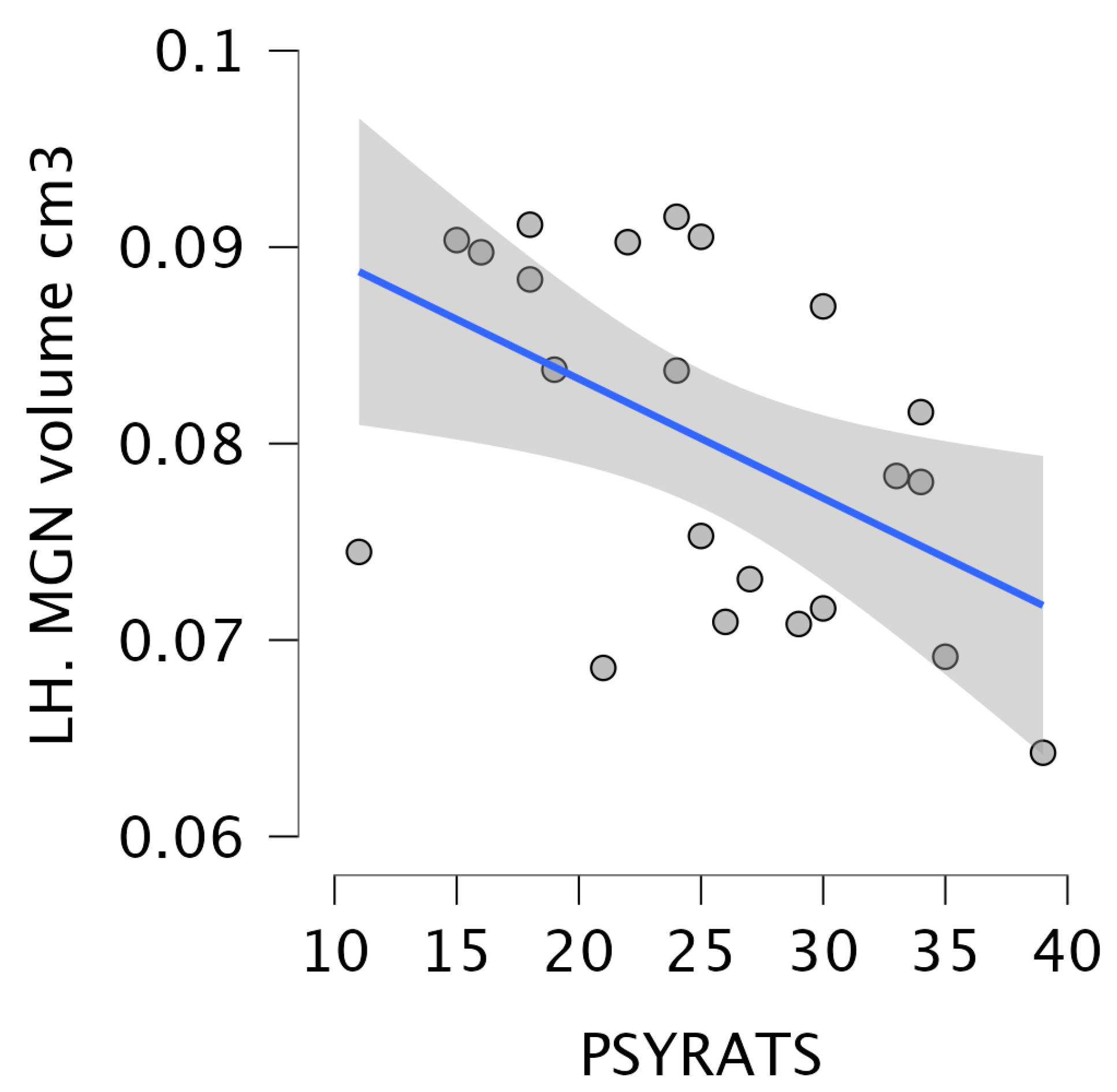

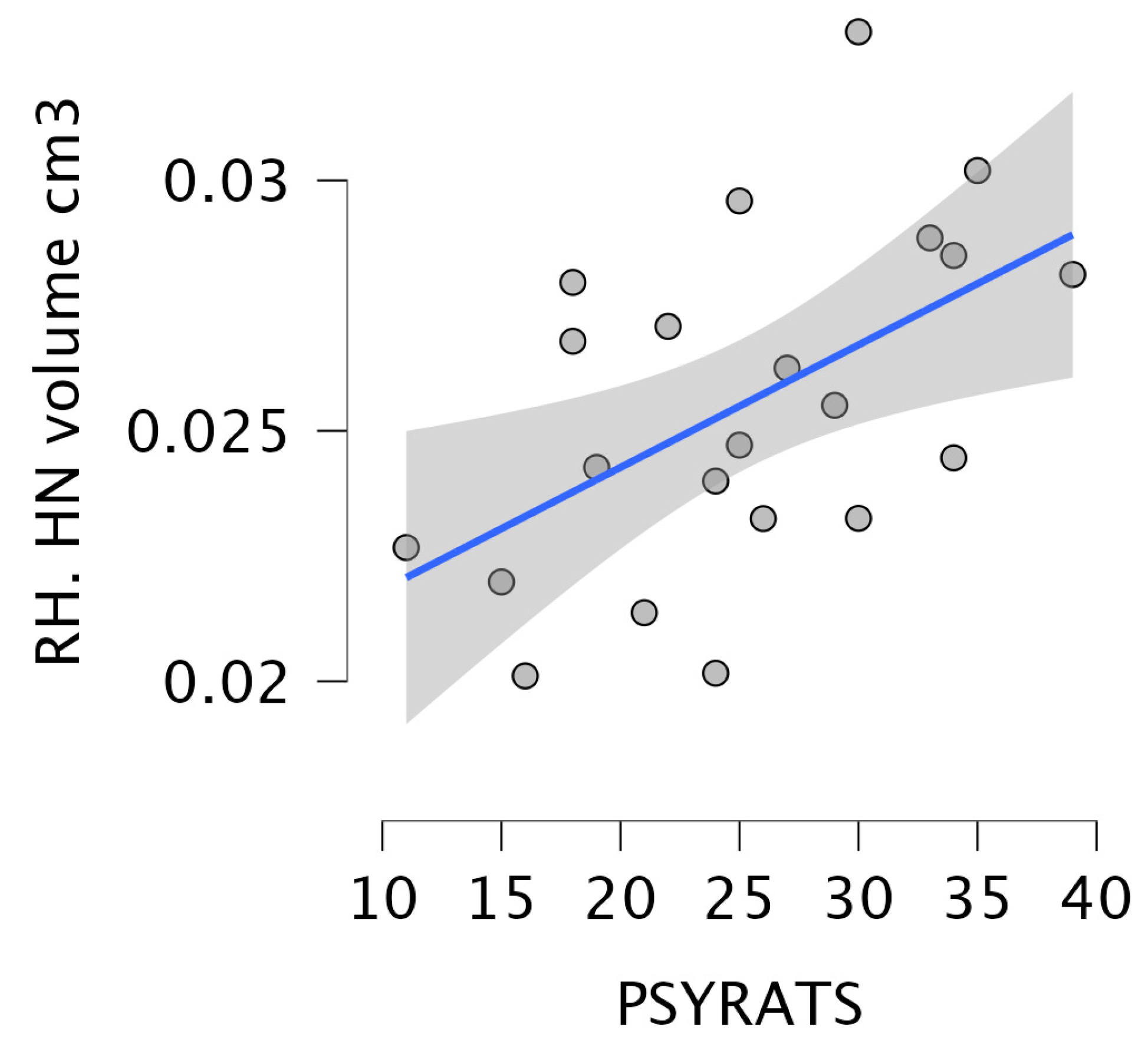

3.5. Correlation Between the Severity of Delusions and Hallucinations and the Volume of Thalamic Nuclei in Schizophrenia Patients with Auditory Hallucinations

3.6. Regression Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Anterior cingulate cortex |

| AI | Asymmetry Index |

| ANTs | Advanced Normalization Tools |

| AVHs | Auditory verbal hallucinations |

| AVN | Anterior ventral nucleus |

| BOLD | Blood-oxygen-level-dependent |

| CN | Centromedian nucleus |

| CTC | Cerebello-thalamo-cortical |

| HAMD | Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression |

| HC | Healthy control |

| HN | Habenular nucleus |

| FFE | Fast Field Echo |

| ICC | Intracranial cavity |

| ICV | Intracranial volumes |

| IFG | Inferior frontal gyrus |

| IQ | Intelligence Quotient |

| ISN | Intermediate space label |

| LGN | Lateral geniculate nucleus |

| MGN | Medial geniculate nucleus |

| MN | Mediodorsal nucleus |

| MNI | Montreal Neurological Institute |

| PANSS | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale |

| PN | Pulvinar nucleus |

| PSYRATS | Psychotic symptom rating scale |

| PV | Partial volume |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| SANLM | Spatially Adaptive Non-Local Means |

| SCZ | Schizophrenia |

| STG | Superior temporal gyrus |

| VAN | Ventral anterior nucleus |

| VLAN | Ventral lateral anterior nucleus |

| VLPN | Ventral lateral posterior nucleus |

| VPLN | Ventral posterior lateral nucleus |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx), [Internet]. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/27a7644e8ad28e739382d31e77589dd7 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Solmi, M.; Seitidis, G.; Mavridis, D.; Correll, C.U.; Dragioti, E.; Guimond, S.; Tuominen, L.; Dargél, A.; Carvalho, A.F.; Fornaro, M.; et al. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of schizophrenia—Data, with critical appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 5319–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuang, M. Schizophrenia: Genes and environment. Biol. Psychiatry 2000, 47, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.; Lewine, R.J. The positive/negative symptom distinction in schizophrenia validity and etiological relevance. Schizophr. Res. 1988, 1, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, N.C.; Flaum, M. Schizophrenia: The characteristic symptoms. Schizophr. Bull. 1991, 17, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larøi, F.; Sommer, I.E.; Blom, J.D.; Fernyhough, C.; Ffytche, D.H.; Hugdahl, K.; Johns, L.C.; McCarthy-Jones, S.; Preti, A.; Raballo, A.; et al. The characteristic features of auditory verbal hallucinations in clinical and nonclinical groups: State-of-the-art overview and future directions. Schizophr. Bull. 2012, 38, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Mathur, P.; Gottesman, I.I.; Nagpal, R.; Nimgaonkar, V.L.; Deshpande, S.N. Correlates of hallucinations in schizophrenia: A cross-cultural evaluation. Schizophr. Res. 2007, 92, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, B.; Munson, J.; Chander, A.; Wang, W.; Brenner, C.J.; Campbell, A.T.; Ben-Zeev, D. The relationship between appraisals of auditory verbal hallucinations and real-time affect and social functioning. Schizophr. Res. 2022, 250, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M.A.; Mathalon, D.H.; Roach, B.J.; Cavus, I.; Spencer, D.D.; Ford, J.M. The Corollary Discharge in Humans Is Related to Synchronous Neural Oscillations. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2011, 23, 2892–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.M.; Roach, B.J.; Faustman, W.O.; Mathalon, D.H. Synch before you speak: Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mathalon, D.H.; Roach, B.J.; Reilly, J.; Keedy, S.K.; Sweeney, J.A.; Ford, J.M. Action planning and predictive coding when speaking. NeuroImage 2014, 91, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćurčić-Blake, B.; Ford, J.M.; Hubl, D.; Orlov, N.D.; Sommer, I.E.; Waters, F.; Allen, P.; Jardri, R.; Woodruff, P.W.; David, O.; et al. Interaction of language, auditory and memory brain networks in auditory verbal hallucinations. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 148, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wu, F.; Ke, X.; Li, R.; Lu, X.; Ning, Y.; Cheng, J.; Moffitt, H.; Kim, I.; Chi, Z.; et al. Reduced gray matter volume of left superior temporal gyrus in schizophrenia with auditory verbal hallucinations: A voxel-based morphometry study. BIO Web Conf. 2017, 8, 01031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ma, C.; Guan, M.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; et al. The underlying neurobiological basis of gray matter volume alterations in schizophrenia with auditory verbal hallucinations: A meta-analytic investigation. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 138, 111331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, I.E.C.; Diederen, K.M.J.; Blom, J.-D.; Willems, A.; Kushan, L.; Slotema, K.; Boks, M.P.M.; Daalman, K.; Hoek, H.W.; Neggers, S.F.W.; et al. Auditory verbal hallucinations predominantly activate the right inferior frontal area. Brain 2008, 131 Pt 12, 3169–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechelli, A.; Allen, P.; Amaro, E.; Fu, C.H.; Williams, S.C.; Brammer, M.J.; Johns, L.C.; McGuire, P.K. Misattribution of speech and impaired connectivity in patients with auditory verbal hallucinations. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2007, 28, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Granados, B.; Brotons, O.; Martínez-Bisbal, M.; Celda, B.; Martí-Bonmati, L.; Aguilar, E.; González, J.; Sanjuán, J. Spectroscopic metabolomic abnormalities in the thalamus related to auditory hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2008, 104, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behroozmand, R.; Shebek, R.; Hansen, D.R.; Oya, H.; Robin, D.A.; Howard, M.A., 3rd; Greenlee, J.D. Sensory-motor networks involved in speech production and motor control: An fMRI study. NeuroImage 2015, 109, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, D.H.; Fox, M.B.; Chapman, B.C.; McAfee, S.S.; Liu, Y. Cerebellar control of thalamocortical circuits for cognitive function: A review of pathways and a proposed mechanism. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1126508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Bolaños, N.; Espinosa, A.; López-Bendito, G. Developmental interactions between thalamus and cortex: A true love reciprocal story. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2018, 52, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Xue, K.; Yang, M.; Wang, H.; Han, S.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Song, X.; Cheng, J. Aberrant Cerebello-Thalamo-Cortical Functional and Effective Connectivity in First-Episode Schizophrenia with Auditory Verbal Hallucinations. Schizophr. Bull. 2022, 48, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shergill, S.S.; Brammer, M.J.; Williams, S.C.R.; Murray, R.M.; McGuire, P.K. Mapping Auditory Hallucinations in Schizophrenia Using Func-tional Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Xi, Y.; Lu, Z.-L.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Zhu, X.; Cui, L.-B.; Tan, Q.; Liu, W.; et al. Decreased bilateral thalamic gray matter volume in first-episode schizophrenia with prominent hallucinatory symptoms: A volumetric MRI study. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinost, D.; Tokoglu, F.; Hampson, M.; Hoffman, R.; Constable, R.T. Data-Driven Analysis of Functional Connectivity Reveals a Potential Auditory Verbal Hallucination Network. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 45, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.J.D. The anterior thalamic nuclei and cognition: A role beyond space? Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 126, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keun, J.T.B.; van Heese, E.M.; Laansma, M.A.; Weeland, C.J.; de Joode, N.T.; Heuvel, O.A.v.D.; Gool, J.K.; Kasprzak, S.; Bright, J.K.; Vriend, C.; et al. Structural assessment of thalamus morphology in brain disorders: A review and recommendation of thalamic nucleus segmentation and shape analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 131, 466–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.J.; Scheffler, K.; Grodd, W. The structural connectivity mapping of the intralaminar thalamic nuclei. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Torremocha, D.; Porrero, C.; Rodriguez-Moreno, J.; García-Amado, M.; Lübke, J.H.R.; Núñez, Á.; Clascá, F. Posterior thalamic nucleus axon terminals have different structure and functional impact in the motor and somatosensory vibrissal cortices. Anat. Embryol. 2019, 224, 1627–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Vidal, J.; Fuentes-Claramonte, P.; Salgado-Pineda, P.; Ramiro, N.; García-León, M.Á.; Torres, M.L.; Arévalo, A.; Guerrero-Pedraza, A.; Munuera, J.; Sarró, S.; et al. Brain correlates of speech perception in schizophrenia patients with and without auditory hallucinations. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjón, J.V.; Coupé, P. volBrain: An Online MRI Brain Volumetry System. Front. Neuroinformatics 2016, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemann, K.; Mennicken, V.; Jeanmonod, D.; Morel, A. The morel stereotactic atlas of the human thalamus: Atlas-to-MR registration of internally consistent canonical model. NeuroImage 2000, 12, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avants, B.B.; Tustison, N.; Song, G. Advanced normalization tools (ANTS). Insight J. 2009, 2, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rando, M.; Elvira, U.K.; García-Martí, G.; Gadea, M.; Aguilar, E.J.; Escarti, M.J.; Ahulló-Fuster, M.A.; Grasa, E.; Corripio, I.; Sanjuan, J.; et al. Alterations in the volume of thalamic nuclei in patients with schizophrenia and persistent auditory hallucinations. NeuroImage Clin. 2022, 35, 103070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ysbæk-Nielsen, A.T.; Gogolu, R.F.; Tranter, M.; Obel, Z.K. Structural brain differences in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders with and without auditory verbal hallucinations. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2024, 344, 111863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danos, P.; Baumann, B.; Krämer, A.; Bernstein, H.-G.; Stauch, R.; Krell, D.; Falkai, P.; Bogerts, B. Volumes of association thalamic nuclei in schizophrenia: A postmortem study. Schizophr. Res. 2003, 60, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.; Koch, K.; Schachtzabel, C.; Schultz, C.C.; Gaser, C.; Reichenbach, J.R.; Sauer, H.; Bär, K.-J.; Schlösser, R.G. Structural basis of the fronto-thalamic dysconnectivity in schizophrenia: A combined DCM-VBM study. NeuroImage Clin. 2013, 3, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, V.; Zöller, D.; Schneider, M.; Schaer, M.; Eliez, S. Abnormal Development and Dysconnectivity of Distinct Thalamic Nuclei in Patients With 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome Experiencing Auditory Hallucinations. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2020, 5, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Hua, Q.; Zhao, X.; Tian, W.; Cao, H.; Xu, W.; Sun, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, K.; Ji, G.-J. Abnormal functional lateralization and cooperation in bipolar disorder are associated with neurotransmitter and cellular profiles. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 369, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Guo, Z.; Cao, H.; Li, H.; Hu, X.; Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Liu, R.; Xu, Y. Altered asymmetries of resting-state MRI in the left thalamus of first-episode schizophrenia. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2022, 8, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Luo, C.; Li, N.; Li, Z.; Duan, M.; Yao, G.; Wang, H.; He, M.; Yao, D. Altered asymmetries of diffusion and volumetry in basal ganglia of schizophrenia. Brain Imaging Behav. 2020, 15, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, K.M.; Molfese, D.L.; Salas, R. The role of the habenula in drug addiction. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalla, A.; Homberg, J.R.; Lipina, T.V.; Sescousse, G.; Luijten, M.; Ivanova, S.A.; Schellekens, A.F.; Loonen, A.J. The role of the habenula in the transition from reward to misery in substance use and mood disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 80, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Han, S.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Song, X.; Cheng, J. Altered static and dynamic functional connectivity of habenula in first-episode, drug-naïve schizophrenia patients, and their association with symptoms including hallucination and anxiety. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1078779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Luan, S.; Yang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H. Altered Volume and Functional Connectivity of the Habenula in Schizo-phrenia. Front Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, B.C.; Andreasen, N.C.; Ziebell, S.; Pierson, R.; Magnotta, V. Long-term Antipsychotic Treatment and Brain Volumes: A Longitudinal Study of First-Episode Schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HC (n = 21) | SZ_AVH− (n = 22) | SZ_AVH+ (n = 22) | Statistical Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.24 ± 14.43 (31.67–44.8) | 45.05 ± 7.54 (41.7–48.39) | 39.18 ± 12.5 (33.64–44.73) | F=2.12 | 0.12 |

| Gender | 15M/6F | 15M/7F | 19M/3F | Χ2 = 2.22 | 0.32 |

| IQ | 100.38 ± 10.3 (95.69–105.07) | 101.32 ± 8.89 (97.38–105.26) | 97.86 ± 9.48 (93.66–102.07) | F = 0.77 | 0.46 |

| PSYRATS | N/A | N/A | 25.23 ± 7.34 (21.97–28.48) | N/A | N/A |

| HC (n = 21) | SZ_AVH− (n = 22) | SZ_AVH+ (n = 22) | Statistical Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICV (cm3) | 1436.12 ± 131.21 (1376.39–1495.85) | 1363.51 ± 130.36 (1305.71–1421.31) | 1391.7 ± 82.15 (1355.28–1428.12) | F = 2.11 | 0.13 |

| Right Hemisphere | Left Hemisphere | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | SCZ_AVH− | SCZ_AVH+ | F | p | HC | SCZ_AVH− | SCZ_AVH+ | F | p | |

| Thalamus | 6.3 ± 0.3 (5.6–7.0) | 6.2 ± 0.4 (5.5–7.2) | 6.2 ± 0.3 (5.5–6.8) | 1.0 | 0.36 | 6.2 ± 0.34 (5.5–6.9) | 6.0 ± 0.4 (5.4–7.0) | 6.0 ± 0.4 (5.3–6.6) | 1.8 | 0.16 |

| AVN | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.07–0.1) | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.05–0.1) | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.08–0.1) | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.08–0.13) | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.07–0.13) | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.05–0.13) | 0.4 | 0.65 |

| VAN | 0.28 ± 0.02 (0.2–0.3) | 0.27 ± 0.02 (0.2–0.3) | 0.28 ± 0.03 (0.2–0.3) | 0.2 | 0.79 | 0.31 ± 0.02 (0.2–0.3) | 0.31 ± 0.03 (0.2–0.3) | 0.32 ± 0.03 (0.2–0.3) | 0.8 | 0.42 |

| VLAN | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.1–0.11) | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.1–0.11) | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.1–0.11) | 0.2 | 0.75 | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.1–0.11) | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.1–0.11) | 0.1 ± 0.01 (0.1–0.11) | 0.4 | 0.65 |

| VLPN | 0.89 ± 0.07 (0.85–0.92) | 0.85 ± 0.08 (0.81–0.88) | 0.84 ± 0.08 (0.8–0.88) | 2.1 | 0.13 | 0.87 ± 0.05 (0.85–0.9) | 0.86 ± 0.07 (0.83–0.89) | 0.85 ± 0.08 (0.81–0.88) | 0.7 | 0.47 |

| VPLN | 0.35 ± 0.03 (0.34–0.37) | 0.34 ± 0.03 (0.33–0.36) | 0.35 ± 0.03 (0.34–0.36) | 0.4 | 0.64 | 0.36 ± 0.04 (0.34–0.38) | 0.35 ± 0.04 (0.33–0.37) | 0.36 ± 0.03 (0.34–0.37) | 0.2 | 0.80 |

| PN | 1.33 ± 0.09 (1.29–1.37) | 1.29 ± 0.13 (1.23–1.35) | 1.27 ± 0.13 (1.22–1.33) | 1.3 | 0.26 | 1.43 ± 0.1 (1.38–1.47) | 1.37 ± 0.14 (1.31–1.43) | 1.37 ± 0.13 (1.31–1.43) | 1.5 | 0.22 |

| LGN | 0.09 ± 0.02 (0.08–0.09) | 0.08 ± 0.02 (0.07–0.09) | 0.08 ± 0.02 (0.07–0.09) | 0.6 | 0.51 | 0.09 ± 0.02 (0.08–0.1) | 0.09 ± 0.02 (0.08–0.09) | 0.08 ± 0.02 (0.08–0.09) | 1.9 | 0.15 |

| MGN | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.08–0.08) | 0.09 ± 0.01 (0.08–0.09) | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.08–0.08) | 4.2 | 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.08–0.08) | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.08–0.09) | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.08–0.08) | 2.2 | 0.11 |

| CN | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.13–0.14) | 0.13 ± 0.02 (0.12–0.14) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.13–0.14) | 0.3 | 0.73 | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.12–0.13) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.12–0.13) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.12–0.14) | 0.6 | 0.53 |

| MN | 0.67 ± 0.04 (0.65–0.69) | 0.67 ± 0.07 (0.63–0.7) | 0.65 ± 0.05 (0.62–0.67) | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.66 ± 0.03 (0.65–0.68) | 0.66 ± 0.06 (0.64–0.69) | 0.65 ± 0.05 (0.63–0.67) | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| HN | 0.02 ± 0 (0.02–0.03) | 0.03 ± 0 (0.03–0.03) | 0.03 ± 0 (0.02–0.03) | 3.7 | 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0 (0.02–0.03) | 0.03 ± 0 (0.03–0.03) | 0.03 ± 0 (0.02–0.03) | 2.1 | 0.12 |

| Comparisons | t | p | 95% CI Limits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| RH. MGN | HC vs. SCZ_AVH− | −2.39 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0 |

| HC vs. SCZ_AVH+ | 0.23 | 1 | −0.01 | 0.01 | |

| SCZ_AVH− vs. SCZ_AVH+ | 2.64 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.01 | |

| RH. HN | HC vs. SCZ_AVH− | −2.73 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 |

| HC vs. SCZ_AVH+ | −1.43 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | |

| SCZ_AVH− vs. SCZ_AVH+ | 1.32 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Asymmetry Index (AI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | SCZ_AVH− | SCZ_AVH+ | F | p | |

| Thalamus | 0.002 ± 0.08 (−0.03–0.03) | −0.05 ± 0.08 (−0.09–−0.01) | −0.03 ± 0.05 (−0.06–−0.01) | 3.07 | 0.054 |

| AVN | −0.03 ± 0.1 (−0.08–0.008) | −0.03 ± 0.1 (−0.08–0.01) | −0.07 ± 0.15 (−0.14–−0.01) | 0.94 | 0.39 |

| VAN | 0.1 ± 0.1 (0.06–0.15) | 0.07 ± 0.12 (0.01–0.12) | 0.11 ± 0.1 (0.06–0.15) | 0.87 | 0.42 |

| VLAN | 0.01 ± 0.11 (−0.03–0.06) | 0.03 ± 0.08 (0.003–0.07) | 0.04 ± 0.09 (0.005–0.08) | 0.45 | 0.63 |

| VLPN | −0.01 ± 0.05 (−0.03–0.01) | 0.01 ± 0.04 (−0.005–0.03) | 0.01 ± 0.04 (−0.009–0.02) | 1.63 | 0.2 |

| VPLN | 0.009 ± 0.05 (−0.01–0.03) | 0.02 ± 0.05 (0.0008–0.04) | 0.02 ± 0.05 (−0.005–0.04) | 0.44 | 0.64 |

| PN | 0.07 ± 0.03 (0.05–0.08) | 0.06 ± 0.04 (0.04–0.08) | 0.07 ± 0.04 (0.05–0.09) | 0.64 | 0.52 |

| LGN | 0.09 ± 0.17 (0.01–0.17) | 0.11 ± 0.22 (0.01–0.2) | 0.02 ± 0.15 (−0.04–0.09) | 1.17 | 0.31 |

| MGN | −0.01 ± 0.1 (−0.06–0.03) | −0.02 ± 0.07 (−0.05–0.01) | 0.04 ± 0.08 (−0.03–0.04) | 0.49 | 0.61 |

| CN | −0.03 ± 0.08 (−0.07–0.001) | 0.005 ± 0.09 (−0.03–0.04) | −0.004 ± 0.08 (−0.04–0.03) | 1.34 | 0.27 |

| MN | −0.009 ± 0.03 (−0.02–0.008) | −0.0001 ± 0.04 (−0.02–0.02) | 0.01 ± 0.04 (−0.01–0.03) | 1.13 | 0.32 |

| HN | 0.03 ± 0.11 (−0.01–0.08) | 0.002 ± 0.1 (−0.04–0.04) | 0.01 ± 0.11 (−0.03–0.07) | 0.51 | 0.6 |

| Regression Model | Age | Gender | IQ | Study Group (SCZ_AVH−) | Study Group (SCZ_AVH+) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | F | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Thalamus | 5 | 4.64 | 0.001 | −0.31 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.02 | −0.26 | 0.02 | −0.12 | 0.35 | −0.2 | 0.13 |

| AVN | 5 | 1.24 | 0.29 | −0.12 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.5 | −0.2 | 0.13 | −0.05 | 0.72 | 0.1 | 0.48 |

| VAN | 5 | 0.75 | 0.59 | −0.02 | 0.85 | 0.09 | 0.51 | −0.17 | 0.18 | −0.07 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.71 |

| VLAN | 5 | 0.85 | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.22 | −0.05 | 0.69 | −0.09 | 0.56 | 0.08 | 0.58 |

| VLPN | 5 | 2.59 | 0.03 | −0.22 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.02 | −0.09 | 0.46 | −0.11 | 0.44 | −0.2 | 0.16 |

| VPLN | 5 | 1.69 | 0.14 | −0.3 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.42 | 0.19 | 0.14 | −0.05 | 0.73 | −0 | 0.99 |

| PN | 5 | 3.97 | 0.003 | −0.36 | 0.003 | 0.19 | 0.1 | −0.21 | 0.08 | −0.1 | 0.48 | −0.21 | 0.11 |

| LGN | 5 | 2.1 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.78 | −0.18 | 0.21 | −0.15 | 0.30 |

| MGN | 5 | 1.8 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.65 | −0.09 | 0.45 | −0.13 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.9 |

| CN | 5 | 2.27 | 0.05 | −0.2 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.56 | −0.34 | 0.009 | 0.07 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 0.67 |

| MN | 5 | 2.35 | 0.05 | −0.18 | 0.16 | 0.1 | 0.43 | −0.3 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.81 | −0.18 | 0.19 |

| HN | 5 | 2.94 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhazmi, F.H. The Involvement of Thalamic Nuclei in Schizophrenia Patients with and Without Auditory Verbal Hallucinations: A Brain Morphometry Study. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090914

Alhazmi FH. The Involvement of Thalamic Nuclei in Schizophrenia Patients with and Without Auditory Verbal Hallucinations: A Brain Morphometry Study. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(9):914. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090914

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhazmi, Fahad H. 2025. "The Involvement of Thalamic Nuclei in Schizophrenia Patients with and Without Auditory Verbal Hallucinations: A Brain Morphometry Study" Brain Sciences 15, no. 9: 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090914

APA StyleAlhazmi, F. H. (2025). The Involvement of Thalamic Nuclei in Schizophrenia Patients with and Without Auditory Verbal Hallucinations: A Brain Morphometry Study. Brain Sciences, 15(9), 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15090914