The Effect of Mental Health First Aid Training on Pharmacist and Pharmacy Student Confidence and Knowledge: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Approach, Search Strategy, and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Analysis

2.3. Study Quality

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

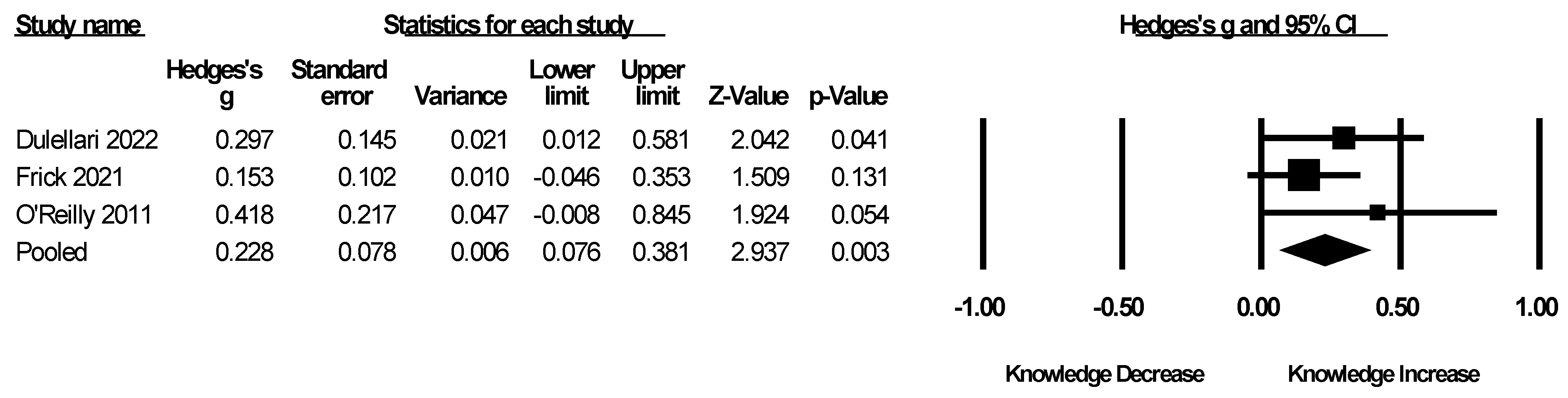

3.2. The Effect of MHFA Training on Knowledge in Pharmacy Populations

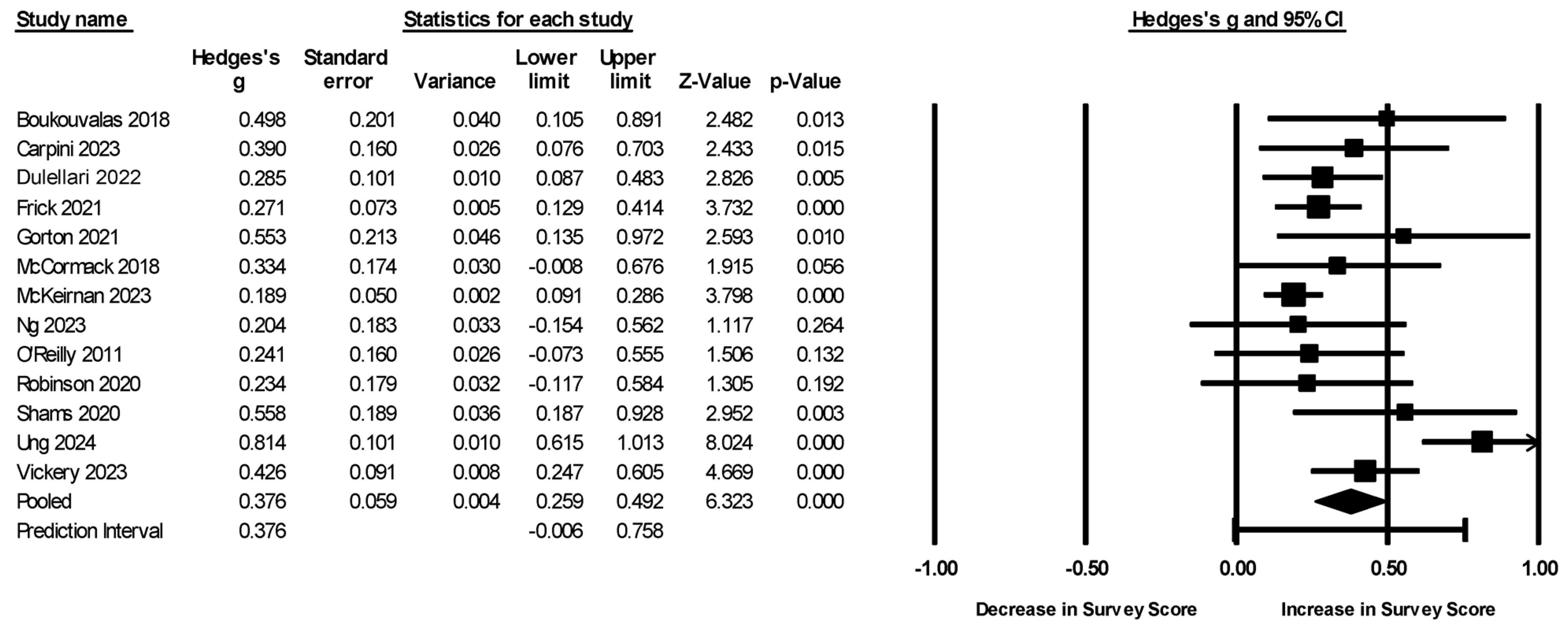

3.3. The Effect of MHFA Training on Attitudinal and Self-Efficacy Measures in Pharmacy Populations

3.4. Subgroup, Moderator, and Sensitivity Analyses for Survey Measures

3.5. Study Quality Assessment

3.6. Narrative Review of Post-Only Studies Without a Control Group

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| MHFA | Mental Health First Aid |

| CMA | Comprehensive Meta-Analysis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

References

- Valliant, S.N.; Burbage, S.C.; Pathak, S.; Urick, B.Y. Pharmacists as Accessible Health Care Providers: Quantifying the Opportunity. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2022, 28, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuyuki, R.T.; Beahm, N.P.; Okada, H.; Al Hamarneh, Y.N. Pharmacists as Accessible Primary Health Care Providers: Review of the Evidence. Can. Pharm. J. CPJ 2018, 151, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, L.; Maney, J.; Martini, N. Changing Perspectives of the Role of Community Pharmacists: 1998–2012. J. Prim. Health Care 2017, 9, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global Burden of Disease and the Impact of Mental and Addictive Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, S.; Bastiampillai, T.; Looi, J.C.; Kisely, S.R.; Lakra, V. The New World Mental Health Report: Believing Impossible Things. Australas. Psychiatry 2023, 31, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moitra, M.; Santomauro, D.; Collins, P.Y.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.; Saxena, S.; Ferrari, A.J. The Global Gap in Treatment Coverage for Major Depressive Disorder in 84 Countries from 2000–2019: A Systematic Review and Bayesian Meta-Regression Analysis. PLoS Med. 2022, 19, e1003901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, C.S.; Smith, T.J.; LaMotte, J.M. A Survey of Pharmacists’ Perceptions of the Adequacy of Their Training for Addressing Mental Health–Related Medication Issues. Ment. Health Clin. 2018, 7, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickles, N.; Wertheimer, A.; Huang, Y. Training Community Pharmacy Staff How to Help Manage Urgent Mental Health Crises. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchener, B.A.; Jorm, A.F. Mental Health First Aid Training in a Workplace Setting: A Randomized Controlled Trial [ISRCTN13249129]. BMC Psychiatry 2004, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.J.; Ross, A.; Reavley, N.J. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Mental Health First Aid Training: Effects on Knowledge, Stigma, and Helping Behaviour. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Advincula, T.J.; Abubakar, M.; Carandang, R.R. Effects of Mental Health First Aid Training in Hospital and Community Pharmacists: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2025, 65, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5 (Updated August 2024); Cochrane: 2024. Available online: www.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Zhu, Q.; Tong, Y.; Wu, T.; Li, J.; Tong, N. Comparison of the Hypoglycemic Effect of Acarbose Monotherapy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Consuming an Eastern or Western Diet: A Systematic Meta-Analysis. Clin. Ther. 2013, 35, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V.; Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Study Quality Assessment Tools | NHLBI, NIH. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Boukouvalas, E.A.; El-Den, S.; Chen, T.F.; Moles, R.; Saini, B.; Bell, A.; O’Reilly, C.L. Confidence and Attitudes of Pharmacy Students towards Suicidal Crises: Patient Simulation Using People with a Lived Experience. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpini, J.A.; Sharma, A.; Kubicki Evans, M.; Jumani, S.; Boyne, E.; Clifford, R.; Ashoorian, D. Pharmacists and Mental Health First Aid Training: A Comparative Analysis of Confidence, Mental Health Assistance Behaviours and Perceived Barriers. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2023, 17, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulellari, S.; Vesey, M.; Mason, N.A.; Marshall, V.D.; Bostwick, J.R. Needs Assessment and Impact of Mental Health Training among Doctor of Pharmacy Students. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2022, 14, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Den, S.; Chen, T.F.; Moles, R.J.; O’Reilly, C. Assessing Mental Health First Aid Skills Using Simulated Patients. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2018, 82, 6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, A.; Osae, L.; Ngo, S.; Anksorus, H.; Williams, C.R.; Rodgers, P.T.; Harris, S. Establishing the Role of the Pharmacist in Mental Health: Implementing Mental Health First Aid into the Doctor of Pharmacy Core Curriculum. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2021, 13, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, H.C.; Macfarlane, H.; Edwards, R.; Farid, S.; Garner, E.; Mahroof, M.; Rasul, S.; Keating, D.; Zaman, H.; Scott, J.; et al. UK and Ireland Survey of MPharm Student and Staff Experiences of Mental Health Curricula, with a Focus on Mental Health First Aid. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2021, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, Z.; Gilbert, J.L.; Ott, C.; Plake, K.S. Mental Health First Aid Training among Pharmacy and Other University Students and Its Impact on Stigma toward Mental Illness. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 1342–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeirnan, K.C.; MacCamy, K.L.; Robinson, J.D.; Ebinger, M.; Willson, M.N. Implementing Mental Health First Aid Training in a Doctor of Pharmacy Program. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 87, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, R.; El-Den, S.; Collins, J.C.; Hu, J.; McMillan, S.S.; Wheeler, A.J.; O’Reilly, C.L. Evaluation of a Training Program to Support the Implementation of a Community Pharmacist-Led Support Service for People Living with Severe and Persistent Mental Illness. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2023, 63, 807–816.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.L.; Bell, J.S.; Kelly, P.J.; Chen, T.F. Impact of Mental Health First Aid Training on Pharmacy Students’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Self-Reported Behaviour: A Controlled Trial. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2011, 45, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams, S.; Hattingh, H.L. Evaluation of Mental Health Training for Community Pharmacy Staff Members and Consumers. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2020, 50, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, T.X.; O’Reilly, C.L.; Moles, R.J.; Collins, J.C.; Ng, R.; Pham, L.; Saini, B.; Ong, J.A.; Chen, T.F.; Schneider, C.R.; et al. Evaluation of Mental Health First Aid Training and Simulated Psychosis Care Role-Plays for Pharmacy Education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2024, 88, 101288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickery, P.B.; Wick, K.; McKee, J. Evaluating the Perceptions of a Required Didactic Mental Health First Aid Training Course among First-Year Pharmacy Students. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2023, 15, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witry, M.J.; Fadare, O.; Pudlo, A. Pharmacy Professionals’ Preparedness to Use Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) Behaviors. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 18, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witry, M.; Karamese, H.; Pudlo, A. Evaluation of Participant Reluctance, Confidence, and Self-Reported Behaviors since Being Trained in a Pharmacy Mental Health First Aid Initiative. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.D.; Maslo, T.E.; McKeirnan, K.C.; Kim, A.P.; Brand-Eubanks, D.C. The Impact of a Mental Health Course Elective on Student Pharmacist Attitudes. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2020, 12, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, K.S.; Jorm, A.F.; Kitchener, B.A.; Reavley, N.J. Mental Health First Aid Training for Australian Medical and Nursing Students: An Evaluation Study. BMC Psychol. 2015, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamgbade, B.A.; Ford, K.H.; Barner, J.C. Impact of a Mental Illness Stigma Awareness Intervention on Pharmacy Student Attitudes and Knowledge. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchener, B.A. Mental Health First Aid Manual. 2007. Available online: https://www.mentalhealthfirstaid.org/product-type/manual-adult/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Li, L.; Ma, X.; Wu, Z.; Xie, C.; Li, Y. Mental Health First Aid Training and Assessment for Healthcare Professionals and Medical Nursing Students: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentala, S.; Thimmajja, S.G.; Vasudevareddy, S.S.; Srinivasan, P.; Desai, M. Impact of Mental Health First Aid Training for Primary Health Care Nurses on Knowledge, Attitude and Referral of Mentally Ill Patients. Indian J. Contin. Nurs. Educ. 2022, 23, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.; Noller, D.T.; Henriquez, M.; Scantamburlo, S.; Ward, I.; Lee, H. Assessing the Utility of Mental Health First Aid Training for Physician Assistant Students. J. Physician Assist. Educ. Off. J. Physician Assist. Educ. Assoc. 2022, 33, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Zhong, D.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Tian, X. Impact of Mental Health First Aid Training Courses on Patients’ Mental Health. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 4623869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowski, A.K.; LaCaille, R.A.; LaCaille, L.J.; Reich, C.M.; Klingner, J. Effectiveness of Mental Health First Aid: A Meta-Analysis. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2019, 24, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.; McDaniel, C.C.; Wang, C.-H.; Garza, K.B. Mental Health and Psychotropic Stigma Among Student Pharmacists. Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 818034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaak, S.; Mantler, E.; Szeto, A. Mental Illness-Related Stigma in Healthcare: Barriers to Access and Care and Evidence-Based Solutions. Healthc. Manag. Forum 2017, 30, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, M.W.; Dower, C.; Winter, P.B.; Rutherford, M.M.; Betts, V.T. Improving Nurses’ Behavioral Health Knowledge and Skills with Mental Health First Aid. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2019, 35, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Study Type | Population | Study Location | Sample Size for MHFA (Control If Applicable) | Outcomes | % Concordance with Quality Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boukouvalas 2018 [17] | Pre–post with control | Pharmacy students | AUS | 40 (146) | Attitudes, confidence | 57 |

| Carpini 2023 [18] | Post with control | Pharmacists | AUS | 90 (71) | Barriers, behaviors, confidence | 75 |

| Dulellari 2022 [19] | Pre–post without control | Pharmacy students | USA | 53 | Confidence, knowledge, perceptions | 67 |

| El-Den 2018 [20] | Post without control | Pharmacy students | AUS | 143 | Behaviors, confidence | 57 |

| Frick 2021 [21] | Pre–post without control | Pharmacy students | USA | 135 | Attitudes, confidence, empathy, knowledge, social distancing | 67 |

| Gorton 2021 [22] | Post with control | Pharmacy students | UK | 26 (205) | Preparedness, stigma | 67 |

| McCormack 2018 [23] | Pre–post without control | Pharmacy students | USA | 34 | Attitudes, social distancing | 58 |

| McKeirnan 2023 [24] | Pre–post without control | Pharmacy students | USA | 212 | Comfort, confidence, stigma | 67 |

| Ng 2023 [25] | Pre–post with control | Pharmacists | AUS | 59 (81) | Attitudes, barriers, behaviors, confidence, social distancing | 71 |

| O’Reilly 2011 [26] | Pre–post with control | Pharmacy students | AUS | 53 (170) | Beliefs, behaviors, knowledge, social distancing | 50 |

| Robinson 2020 [32] | Pre–post without control | Pharmacy students | USA | 40 | Attitudes, behaviors, social distancing | 67 |

| Shams 2020 [27] | Pre–post without control | Pharmacists | AUS | 32 | Attitudes, behaviors | 67 |

| Ung 2024 [28] | Pre–post without control | Pharmacy students | AUS | 148 | Confidence, social distancing | 75 |

| Vickery 2023 [29] | Pre–post without control | Pharmacy students | USA | 69 | Benefits, confidence | 75 |

| Witry 2020a [30] | Post without control | Pharmacists and pharmacy students | USA | 96 | Behaviors, preparedness | 50 |

| Witry 2020b [31] | Post without control | Pharmacists and pharmacy students | USA | 98 | Behaviors, confidence, reluctance | 50 |

| Study | Number of Questions | Answer Type | Topics | Previously Used? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dulellari 2022 [19] | 16 | Agree or Disagree | Depression, anxiety, psychosis, and substance misuse. | Yes [33] |

| Frick 2021 [21] | 10 | True or False | Medications, identifying various types of mental illnesses, and recognizing misconceptions related to mental illness. | Yes [34] |

| O’Reilly 2011 [26] | 1 (open-ended) | Correctly Identified Disorder | Identification of depression and schizophrenia disorders in vignettes. | No |

| Subgroup Variable | Number of Studies | Hedges’ G [95% CI] | Effect Size p-Value | Q/I2 | Q Statistic p-Value | Trim-and-Fill Hedges’ G | Egger’s Intercept | Fail-Safe N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup Analysis by Question Type | ||||||||

| Attitude | 7 | 0.241 [0.127, 0.355] | <0.001 | 3.841/0% | 0.698 | 0.241 | 1.476 | 26 |

| Behavior | 5 | 0.280 [0.123, 0.438] | <0.001 | 4.457/10% | 0.348 | 0.321 | 7.309 | 14 |

| Confidence | 8 | 0.521 [0.288, 0.753] | <0.001 | 44.787/84% | <0.001 | 0.593 | 4.147 | 26 |

| Social Distancing Scale | 6 | 0.302 [0.188, 0.415] | <0.001 | 4.969/0% | 0.420 | 0.326 | −0.397 | 34 |

| Stigma | 3 | 0.226 [0.027, 0.424] | 0.026 | 3.948/49% | 0.139 | 0.201 | 0.817 | 6 |

| Subgroup Analysis by Study Design | ||||||||

| Post with Control | 3 | 0.376 [0.171, 0.582] | <0.001 | 1.340/0% | 0.512 | 0.320 | 2.690 | 8 |

| Pre–Post without Control | 8 | 0.383 [0.228, 0.537] | <0.001 | 34.434/80% | <0.001 | 0.415 | 2.320 | 215 |

| Pre–Post with Control | 3 | 0.297 [0.095, 0.500] | 0.004 | 1.385/0% | 0.500 | 0.297 | 5.390 | 4 |

| Subgroup Analysis by Location | ||||||||

| Australia | 6 | 0.467 [0.244, 0.690] | <0.001 | 15.077/67% | 0.010 | 0.534 | −4.910 | 84 |

| USA | 6 | 0.264 [0.190, 0.339] | <0.001 | 5.654/12% | 0.341 | 0.216 | 1.246 | 81 |

| Subgroup Analysis by Population Type | ||||||||

| Pharmacy Students | 10 | 0.376 [0.239, 0.512] | <0.001 | 35.073/74% | <0.001 | 0.417 | 1.732 | 271 |

| Pharmacists | 3 | 0.381 [0.182, 0.580] | <0.001 | 1.817/0% | 0.403 | 0.309 | 1.473 | 9 |

| Subgroup Analysis by Study Quality | ||||||||

| Moderate | 10 | 0.255 [0.190, 0.321] | <0.001 | 8.212/0% | 0.513 | 0.225 | 1.306 | 143 |

| High | 3 | 0.553 [0.272, 0.834] | <0.001 | 9.532/79% | 0.009 | 0.568 | −1.661 | 57 |

| Study | Outcomes |

|---|---|

| El-Den 2018 [20] | For all confidence questions, at least 84% of students agreed or strongly agreed with each confidence prompt. Five confidence prompts showed 95% of students agreeing or strongly agreeing. For the analysis of behaviors, at least 80% of students performed the correct behavior for 7 of the 10 assessed suicide behaviors and 7 of the 11 assessed postnatal depression behaviors. |

| Witry 2020a [30] | For preparedness assessments, all prompts had at least 74% of participants agreeing or strongly agreeing that they were prepared to perform the behavior after MHFA training. Seven of thirteen behaviors had at least 90% agreeing or strongly agreeing for preparedness. Regarding behaviors, 80% or more participants reported performing two of seven behaviors. |

| Witry 2020b [31] | For reluctance measures, at least 74% disagreed or strongly disagreed that they were reluctant to perform an action for 3 of the 6 items assessed. For confidence, all 7 measures showed at least 82% agreeing or strongly agreeing that they were confident. For self-reported behaviors, at least 70% of participants responded yes for performing 3 of 9 behaviors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frond, D.; Habba, S.; Stewart, B.; Burghardt, K.J. The Effect of Mental Health First Aid Training on Pharmacist and Pharmacy Student Confidence and Knowledge: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080816

Frond D, Habba S, Stewart B, Burghardt KJ. The Effect of Mental Health First Aid Training on Pharmacist and Pharmacy Student Confidence and Knowledge: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(8):816. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080816

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrond, David, Shannon Habba, Brittany Stewart, and Kyle J. Burghardt. 2025. "The Effect of Mental Health First Aid Training on Pharmacist and Pharmacy Student Confidence and Knowledge: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Brain Sciences 15, no. 8: 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080816

APA StyleFrond, D., Habba, S., Stewart, B., & Burghardt, K. J. (2025). The Effect of Mental Health First Aid Training on Pharmacist and Pharmacy Student Confidence and Knowledge: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sciences, 15(8), 816. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15080816