The Key Role of Personality Functioning in Understanding the Link Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Loneliness: A Cross-Sectional Mediation Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Data

2.2.2. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

2.2.3. Personality Functioning (PF)

2.2.4. Loneliness

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics (See Table 1)

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 25.96 | 10.19 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | Gender | 0.30 | 0.95 | −0.02 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | Relationship Status | 1.48 | 0.50 | −0.26 | *** | −0.20 | *** | ||||||||||

| 4 | ACEs | 6.78 | 7.20 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.11 | * | ||||||||||

| 5 | Loneliness | 1.64 | 0.50 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.20 | *** | 0.22 | *** | ||||||||

| 6 | PFtotal | 23.13 | 5.98 | −0.24 | *** | 0.11 | * | 0.22 | *** | 0.24 | *** | 0.60 | *** | ||||

| 7 | PFself | 12.81 | 4.04 | −0.28 | *** | 0.13 | * | 0.21 | *** | 0.29 | *** | 0.59 | *** | 0.93 | *** | ||

| 8 | PFinterpersonal | 10.32 | 2.69 | −0.10 | 0.05 | 0.17 | *** | 0.09 | 0.45 | *** | 0.83 | *** | 0.56 | *** |

3.2. Analysis Strategy

3.2.1. Association Between Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), Personality Functioning, and Loneliness (See Table 2, Models A1–A4)

| Model A1 PFtotal | Model A2 PFself | Model A3 PFinterpersonal | Model A4 Loneliness | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE (B) | β | B | SE (B) | β | B | SE (B) | β | B | SE (B) | β | |||||

| Age | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.20 | *** | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.25 | *** | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.06 | ||

| Gender | 1.80 | 0.64 | 0.14 | ** | 1.27 | 0.42 | 0.15 | ** | 0.51 | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.08 | ||

| Relationship Status | 2.00 | 0.65 | 0.17 | ** | 1.13 | 0.42 | 0.14 | ** | 0.87 | 0.31 | 0.16 | ** | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.18 | ** |

| ACEs | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.23 | *** | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.29 | *** | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.20 | *** | |

| R2adj. | 0.14 | *** | 0.19 | *** | 0.03 | ** | 0.08 | *** | ||||||||

3.2.2. Association Between Types of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), Personality Functioning, and Loneliness (See Table 3)

| PFtotal | PFself | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE (B) | β | p | B | SE (B) | β | p | |||

| Age | −0.11 | 0.03 | −0.19 | 0.000 | * | −0.10 | 0.02 | −0.24 | 0.000 | * |

| Gender | 0.79 | 0.34 | 0.13 | 0.020 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.014 | ||

| Relationship Status | 1.99 | 0.65 | 0.17 | 0.002 | * | 1.15 | 0.42 | 0.14 | 0.007 | * |

| Physical Violence | −0.59 | 0.29 | −0.13 | 0.042 | −0.28 | 0.19 | −0.09 | 0.131 | ||

| Verbal Violence | 0.62 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.025 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.079 | ||

| Emotional Violence | −0.08 | 0.34 | −0.02 | 0.819 | −0.02 | 0.22 | −0.01 | 0.944 | ||

| Non-Verbal Emotional Violence | 0.09 | 0.32 | 0.03 | 0.779 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.917 | ||

| Sexual Violence | 0.94 | 0.58 | 0.09 | 0.107 | 1.18 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.002 | * | |

| Emotional Neglect | 0.75 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.002 | * | 0.61 | 0.15 | 0.25 | 0.000 | * |

| Physical Neglect | −0.41 | 0.47 | −0.05 | 0.383 | −0.23 | 0.30 | −0.04 | 0.450 | ||

| R2adj. | 0.17 | 0.23 | ||||||||

| PFinterpersonal | Loneliness | |||||||||

| B | SE (B) | β | p | B | SE (B) | β | p | |||

| Age | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.290 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.152 | ||

| Gender | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.132 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.349 | ||

| Relationship Status | 0.84 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.007 | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.007 | ||

| Physical Violence | −0.30 | 0.14 | −0.15 | 0.028 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.847 | ||

| Verbal Violence | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.022 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.442 | ||

| Emotional Violence | −0.06 | 0.16 | −0.04 | 0.703 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.781 | ||

| Non-Verbal Emotional Violence | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.658 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.477 | ||

| Sexual Violence | −0.24 | 0.28 | −0.05 | 0.389 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.260 | ||

| Emotional Neglect | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.206 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.000 | * | |

| Physical Neglect | −0.18 | 0.22 | −0.05 | 0.425 | −0.16 | 0.04 | −0.23 | 0.000 | * | |

| R2adj. | 0.05 | 0.13 | ||||||||

- (1)

- Emotional neglect → total level of personality functioning → loneliness.

- (2)

- Emotional neglect and sexual violence → self-functioning → loneliness.

3.2.3. Association Between Personality Functioning and Loneliness (Table 4, Models B1–B2)

| Model B1 Loneliness | Model B2 Loneliness | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE (B) | β | B | SE (B) | β | |||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | ||

| Gender | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | ||

| Relationship Status | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.09 | ||

| PFtotal | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.60 | *** | ||||

| PFself | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.51 | *** | ||||

| PFinterpersonal | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.15 | ** | ||||

| R2adj. | 0.36 | *** | 0.37 | *** | ||||

3.2.4. Mediation Modelling (See Table 5)

| Std. Total Effect | Std. Direct Effect | Std. Indirect Effect | Κ2 | PM | Result | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Point Est. | 95% CI | Point Est. | 95% CI | Point Est. | 95% CI | |||||

| MED1/Mediator: PFtotal | ||||||||||

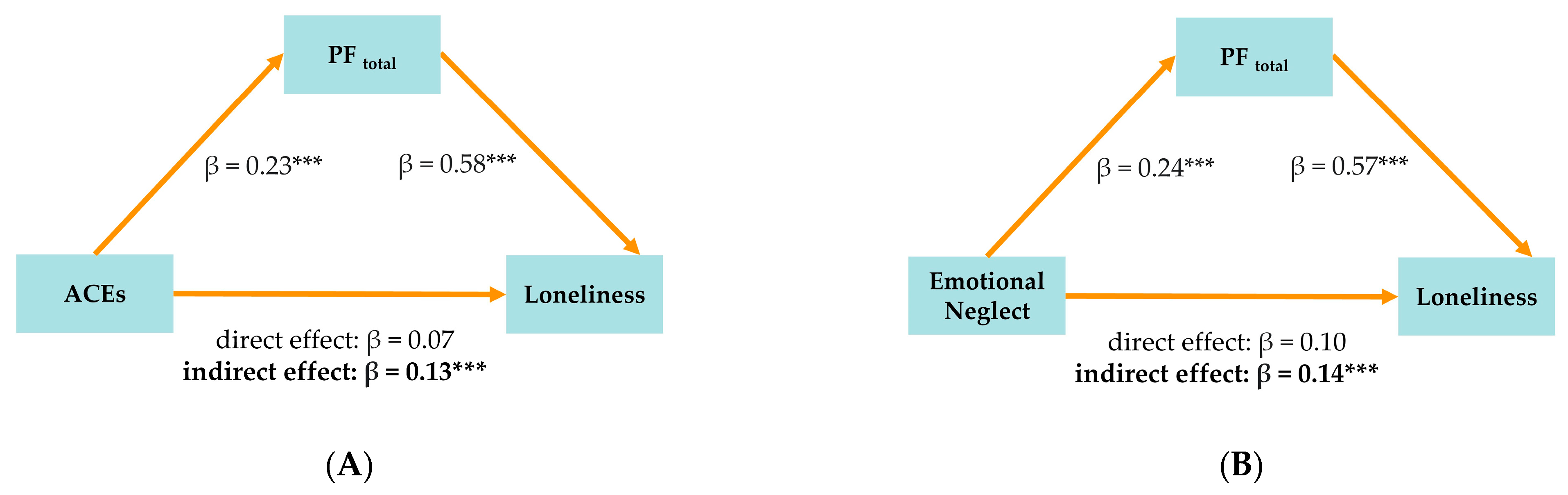

| 1.1 | ACEs → Loneliness | 0.20 | [0.09, 0.31] | 0.07 | [−0.04, 0.17] | 0.13 | [0.07, 0.20] | 0.15 | 0.64 | Full mediation |

| 1.2 | Emotional Neglect → Loneliness | 0.24 | [0.12, 0.36] | 0.10 | [−0.01, 0.20] | 0.14 | [0.08, 0.20] | 0.16 | 0.57 | Full mediation |

| MED2/Mediator: PFself | ||||||||||

| 2.1 | ACEs → Loneliness | 0.20 | [0.09, 0.31] | 0.03 | [−0.08, 0.14] | 0.17 | [0.10, 0.23] | 0.18 | 0.78 | Full mediation |

| 2.2 | Emotional Neglect → Loneliness | 0.22 | [0.10, 0.34] | 0.07 | [−0.03, 0.17] | 0.15 | [0.09, 0.22] | / | / | Full mediation |

| Sexual Violence → Loneliness | 0.07 | [−0.10, 0.24] | −0.03 | [−0.20, 0.14] | 0.10 | [0.05, 0.15] | / | / | Full mediation | |

3.2.5. Model Series MED1: PFtotal as Mediator (See Figure 1A,B)

3.2.6. Model Series MED2: PFself as Mediator (See Figure 2A,B)

3.2.7. Model Fit (See Table 6)

| X2 | df | RMSEA | SRMR | TLI | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MED1.1 | 5.82 | 4 | 0.037 | 0.027 | 0.972 | 0.992 |

| MED1.2 | 5.43 | 4 | 0.033 | 0.025 | 0.978 | 0.994 |

| MED2.1 | 5.88 | 4 | 0.038 | 0.027 | 0.973 | 0.993 |

| MED2.2 | 10.16 | 7 | 0.037 | 0.032 | 0.969 | 0.990 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Personality Functioning as a Predictor of Loneliness

4.2. Personality Functioning as a Mediator Between Childhood Trauma and Loneliness

4.3. A Dimensional Personality Perspective to Understanding Loneliness

5. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Social Isolation and Loneliness Among Older People: Advocacy Brief. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030749 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Krankenkasse, T. Einsamkeitsreport 2024. Available online: https://www.tk.de/resource/blob/2186830/73239d0d1b389491c47f1bf7960ed254/2024-tk-einsamkeitsreport-data.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C.; Ernst, J.M.; Burleson, M.; Berntson, G.G.; Nouriani, B.; Spiegel, D. Loneliness within a nomological net: An evolutionary perspective. J. Res. Personal. 2006, 40, 1054–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Caballero, F.F.; Martin-Maria, N.; Cabello, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Miret, M. Association of loneliness with all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stravynski, A.; Boyer, R. Loneliness in relation to suicide ideation and parasuicide: A population-wide study. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2001, 31, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, M.; Holt-Lunstad, J.; Badcock, J. Loneliness: Contemporary insights into causes, correlates, and consequences. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2010, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richman, N.E.; Sokolove, R.L. The experience of aloneness, object representation, and evocative memory in borderline and neurotic patients. Psychoanal. Psychol. 1992, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Research Centre Data Catalogue. EU Loneliness Survey. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/89h/82e60986-9987-4610-ab4a-84f0f5a9193b (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Berlingieri, F.C.; Colagrossi, M.; Mauri, C. Loneliness and Social Connectedness: Insights from a New EU-Wide Survey. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC133351 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Kovacic, M.; Schnepf, S. Loneliness, Health and Adverse Childhood Experiences. 2023. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC134036 (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Winnicott, D.W. The Capacity to Be Alone. Int. J. Psycho-Anal. 1958, 39, 416–420. [Google Scholar]

- Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Galvano, D.; Favaro, A.; Ostinelli, E.G.; Noventa, V.; Favaretto, E.; Tudor, F.; Finessi, M.; Shin, J.I.; et al. Factors Associated With Loneliness: An Umbrella Review Of Observational Studies. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 271, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonelli-Salgado, T.; Monteiro, G.M.C.; Marcon, G.; Roza, T.H.; Zimerman, A.; Hoffmann, M.S.; Cao, B.; Hauck, S.; Brunoni, A.R.; Passos, I.C. Loneliness, but not social distancing, is associated with the incidence of suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 outbreak: A longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 290, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanskanen, J.; Anttila, T. A Prospective Study of Social Isolation, Loneliness, and Mortality in Finland. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 2042–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, E.Y.; Waite, L.J. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2009, 50, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Burleson, M.H.; Berntson, G.G.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness in everyday life: Cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2003, 46 (Suppl. S3), S39–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhard, M.A.; Rek, S.V.; Nenov-Matt, T.; Barton, B.B.; Dewald-Kaufmann, J.; Merz, K.; Musil, R.; Jobst, A.; Brakemeier, E.L.; Bertsch, K.; et al. Association of loneliness and social network size in adulthood with childhood maltreatment: Analyses of a population-based and a clinical sample. Eur. Psychiatry 2022, 65, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellis, M.A.; Hughes, K.; Cresswell, K.; Ford, K. Comparing relationships between single types of adverse childhood experiences and health-related outcomes: A combined primary data study of eight cross-sectional surveys in England and Wales. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e072916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Heer, C.; Bi, S.; Finkenauer, C.; Alink, L.; Maes, M. The association between child maltreatment and loneliness across the lifespan: A systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. Child Maltreat. 2024, 29, 388–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhtabi, S.; Pitman, A.; Toh, G.; Birken, M.; Pearce, E.; Johnson, S. The experience of loneliness among people with a “personality disorder” diagnosis or traits: A qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, N.; Banerjee, R. Differentiated associations between childhood maltreatment experiences and social understanding: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Dev. Rev. 2013, 33, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, P.; Shevlin, M.; Cloitre, M.; Karatzias, T.; Vallieres, F.; McGinty, G.; Fox, R.; Power, J.M. Quality not quantity: Loneliness subtypes, psychological trauma, and mental health in the US adult population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2019, 54, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.; Luchetti, M.; Prendergast, C.; Ahern, E.; Creaven, A.-M.; Kirwan, E.; Graham, E.K.; O’Súilleabháin, P.S. Adverse childhood experiences and loneliness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social. Sci. Med. 2025, 370, 117860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Cacioppo, S. The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet 2018, 391, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Seijas, C.; Ruggero, C.; Eaton, N.R.; Krueger, R.F. The DSM-5 alternative model for personality disorders and clinical treatment: A review. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2019, 6, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, D.S.; Morey, L.C.; Skodol, A.E. Toward a model for assessing level of personality functioning in DSM-5, part I: A review of theory and methods. In Personality Assessment in the DSM-5; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 35–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, R.; Tyrer, P. Diagnosis and classification of personality disorders: Novel approaches. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2019, 32, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Personality trait structure as a human universal. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R. Language and individual differences: The search for universals in personality lexicons. Rev. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1981, 2, 141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, A.L.; Greene, A.L.; Ringwald, W.; Forbes, M.K.; Brandes, C.M.; Levin-Aspenson, H.F.; Delawalla, C. Factor analysis in personality disorders research: Modern issues and illustrations of practical recommendations. Personal. Disord. 2023, 14, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.G.C. The current state and future of factor analysis in personality disorder research. Personal. Disord. 2017, 8, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.G.; Zimmermann, J. At the nexus of science and practice: Answering basic clinical questions in personality disorder assessment and diagnosis with quantitative modeling techniques. In Personality Disorders: Toward Theoretical and Empirical Integration in Diagnosis and Assessment; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases (11th Revision); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Morey, L.C.; Berghuis, H.; Bender, D.S.; Verheul, R.; Krueger, R.F.; Skodol, A.E. Toward a model for assessing level of personality functioning in DSM-5, part II: Empirical articulation of a core dimension of personality pathology. In Personality Assessment in the DSM-5; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2014; pp. 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Malone, J.C.; Ansell, E.B.; Sanislow, C.A.; Grilo, C.M.; McGlashan, T.H.; Pinto, A.; Markowitz, J.C.; Shea, M.T.; Skodol, A.E.; et al. Personality assessment in DSM-5: Empirical support for rating severity, style, and traits. J. Pers. Disord. 2011, 25, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, J.; Hopwood, C.J.; Krueger, R.F. The DSM-5 level of personality functioning scale. In Oxford Textbook of Psychopathology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 579–603. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Cao, J. Progress in understanding personality functioning in light of the DSM-5 and ICD-11. Asian J. Psychiatry 2024, 102, 104259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, B.; Tracy, M. Clinical utility of the alternative model of personality disorders: A 10th year anniversary review. Personal. Disord. Theory Res. Treat. 2022, 13, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, A.W.; Fonagy, P. Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg, O.F.; Caligor, E. A psychoanalytic theory of personality disorders. In Major Theories of Personality Disorder; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss; Random House: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C.M.; Simms, L.J. Do self and interpersonal dysfunction cross-sectionally mediate the association between adverse childhood experiences and personality pathology? Personal. Ment. Health 2023, 17, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- d’Huart, D.; Seker, S.; Bürgin, D.; Birkhölzer, M.; Boonmann, C.; Schmid, M.; Schmeck, K. The stability of personality disorders and personality disorder criteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 102, 102284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, M.; Brähler, E.; Kampling, H.; Kruse, J.; Fegert, J.M.; Plener, P.L.; Beutel, M.E. Is the end in the beginning? Child maltreatment increases the risk of non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts through impaired personality functioning. Child. Abus. Negl. 2022, 133, 105870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thekkumthala, D.; Schauer, M.; Ruf-Leuschner, M.; Elbert, T.; Seitz, K.I.; Gerhardt, S.; von Schroeder, C.; Schalinski, I. KERF-40-I. Belastende Kindheitserfahrungen (inklusive Zeitleisten) [Verfahrensdokumentation, Instrument, Auswertungsanleitung, Item-Skalenzugehörigkeit, Auswertungsbeispiel, Syntax und Datenbank]. In Leibniz-Institut für Psychologie (ZPID) (Hrsg.), Open Test Archive; ZPID: Trier, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Bremner, J.D.; Walker, J.D.; Whitfield, C.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, K.; Gillis, J.; Nicolau, I.; Wade, T.J. Capturing risk associated with childhood adversity: Independent, cumulative, and multiplicative effects of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and family violence on mental disorders and suicidality. Perm. J. 2020, 24, 19.079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutsebaut, J.; Feenstra, D.J.; Kamphuis, J.H. Development and Preliminary Psychometric Evaluation of a Brief Self-Report Questionnaire for the Assessment of the DSM-5 level of Personality Functioning Scale: The LPFS Brief Form (LPFS-BF). Personal. Disord. 2016, 7, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, C.; Müller, S.; Kerber, A.; Hutsebaut, J.; Brähler, E.; Zimmermann, J. Die deutsche version der level of personality functioning scale-brief form 2.0 (LPFS-BF): Faktorenstruktur, konvergente validität und normwerte in der allgemeinbevölkerung. PPmP-Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2021, 71, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.; Peplau, L.A.; Cutrona, C.E. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N.; Bortz, J. Psychometrische einsamkeitsforschung: Deutsche neukonstruktion der UCLA loneliness scale. Diagnostica 1993, 39, 224–239. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model.—A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Kelley, K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol. Methods 2011, 16, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The ACE Study Survey Data; [Unpublished Data]; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, M.R.; Schreindorfer, L.S.; Haupt, A.L. The role of low self-esteem in emotional and behavioral problems: Why is low self-esteem dysfunctional? J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1995, 14, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, N.E.; Yarcheski, A.; Yarcheski, T.J.; Cannella, B.L.; Hanks, M.M. A meta-analytic study of predictors for loneliness during adolescence. Nurs. Res. 2006, 55, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G.L.; Goldstein, A.L.; Pechenkov, I.G.; Nepon, T.; Wekerle, C. Antecedents, correlates, and consequences of feeling like you don’t matter: Associations with maltreatment, loneliness, social anxiety, and the five-factor model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 92, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D. Psychological maltreatment and loneliness in Chinese children: The role of perceived social support and self-esteem. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 108, 104573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakau, L.; Tibubos, A.N.; Beutel, M.E.; Ehrenthal, J.C.; Gieler, U.; Brahler, E. Personality functioning as a mediator of adult mental health following child maltreatment. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 291, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagnino, P.; Ugarte, M.J.; Morales, F.; González, S.; Saralegui, D.; Ehrenthal, J.C. Risk factors for adult depression: Adverse childhood experiences and personality functioning. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 594698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualter, P.; Vanhalst, J.; Harris, R.; Van Roekel, E.; Lodder, G.; Bangee, M.; Maes, M.; Verhagen, M. Loneliness across the life span. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beadle, J.N.; Keady, B.; Brown, V.; Tranel, D.; Paradiso, S. Trait empathy as a predictor of individual differences in perceived loneliness. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 110, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, S.N.; Flechsenhar, A.; Bertsch, K.; Zettl, M. Childhood traumatic experiences and dimensional models of personality disorder in DSM-5 and ICD-11: Opportunities and challenges. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, S.N.; Zettl, M.; Bertsch, K.; Taubner, S. Persönlichkeitsfunktionsniveau, maladaptive Traits und Kindheitstraumata. Psychotherapeut 2020, 65, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D.; Blatt, S.J. Internal working models and the representational world in attachment and psychoanalytic theories. In Proceedings of the 100th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 1992; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P. Attachment, mentalizing, and the self. In Handbook of Personality Disorders; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg, O. The treatment of patients with borderline personality organization. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1968, 49, 600–619. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg, O.F. Object Relations Theory and Clinical Psychoanalysis; Jason Aronson: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kernberg, O.F.; Yeomans, F.E.; Clarkin, J.F.; Levy, K.N. Transference focused psychotherapy: Overview and update. Int. J. Psychoanal. 2008, 89, 601–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, A.; Fonagy, P. Mentalization-Based Treatment for Personality Disorders: A Practical Guide; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maerz, J.; Viviani, R.; Labek, K. The Key Role of Personality Functioning in Understanding the Link Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Loneliness: A Cross-Sectional Mediation Analysis. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15060551

Maerz J, Viviani R, Labek K. The Key Role of Personality Functioning in Understanding the Link Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Loneliness: A Cross-Sectional Mediation Analysis. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(6):551. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15060551

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaerz, Jeff, Roberto Viviani, and Karin Labek. 2025. "The Key Role of Personality Functioning in Understanding the Link Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Loneliness: A Cross-Sectional Mediation Analysis" Brain Sciences 15, no. 6: 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15060551

APA StyleMaerz, J., Viviani, R., & Labek, K. (2025). The Key Role of Personality Functioning in Understanding the Link Between Adverse Childhood Experiences and Loneliness: A Cross-Sectional Mediation Analysis. Brain Sciences, 15(6), 551. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15060551