Impathy and Emotion Recognition: How Attachment Shapes Self- and Other-Focused Emotion Processing

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Focused Emotion Processing: Intrapersonal Emotion Perception

1.2. Other-Focused Emotion Processing: Interpersonal Emotion Perception

1.3. Defensive Exclusion as a Possible Mechanism for Impairing Emotion Perception

1.4. Aim of the Present Study and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Adult Attachment Projective Picture System (AAP)

2.3.2. Symptom-Checklist-90-Standard (SCL-90-S)

2.3.3. Impathy Inventory

2.3.4. Reliable Emotional Action Decoding Test, 64-Item Version (READ-64 Test)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Hypothesis Testing

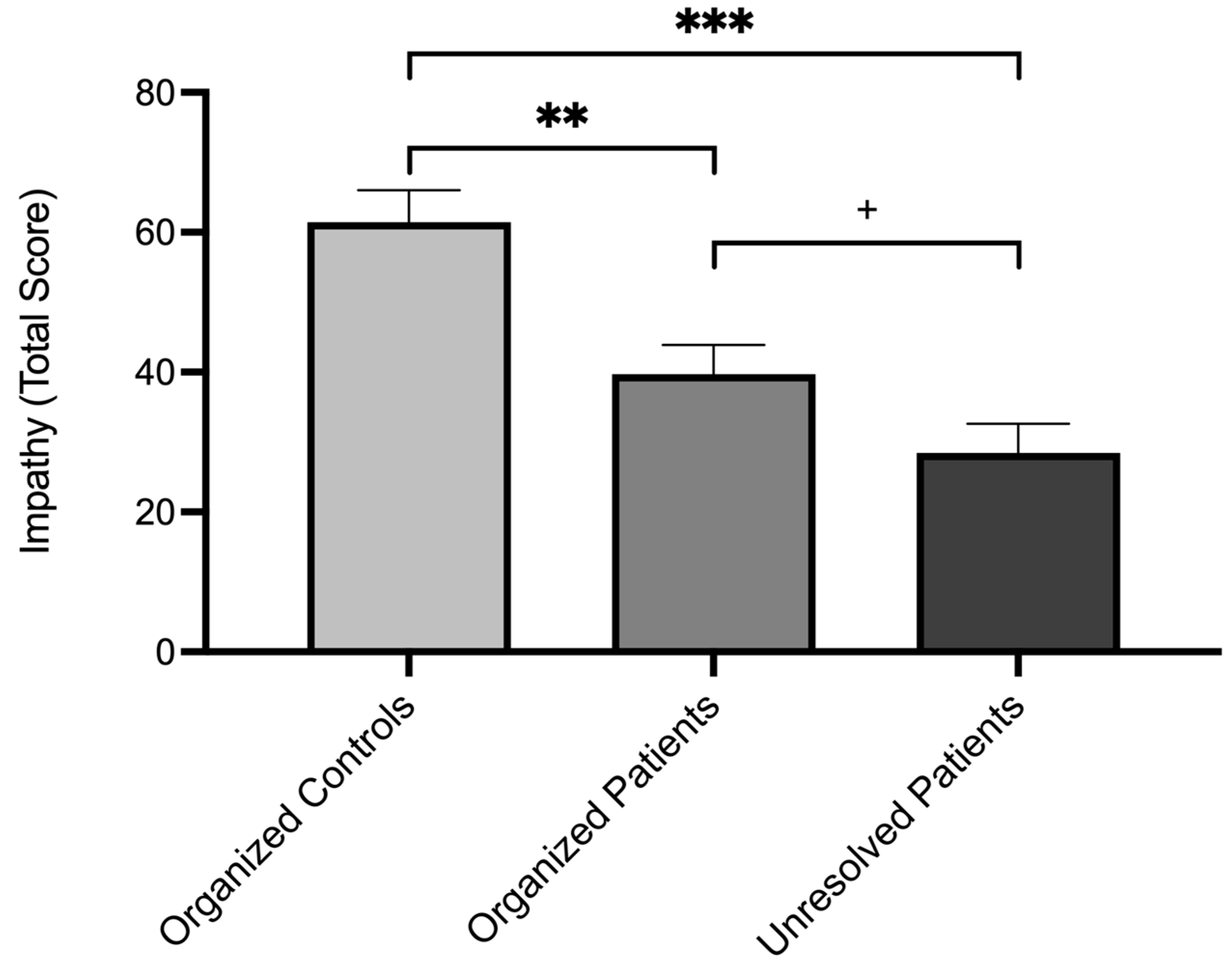

3.2.1. Intrapersonal Emotion Perception: Impathy

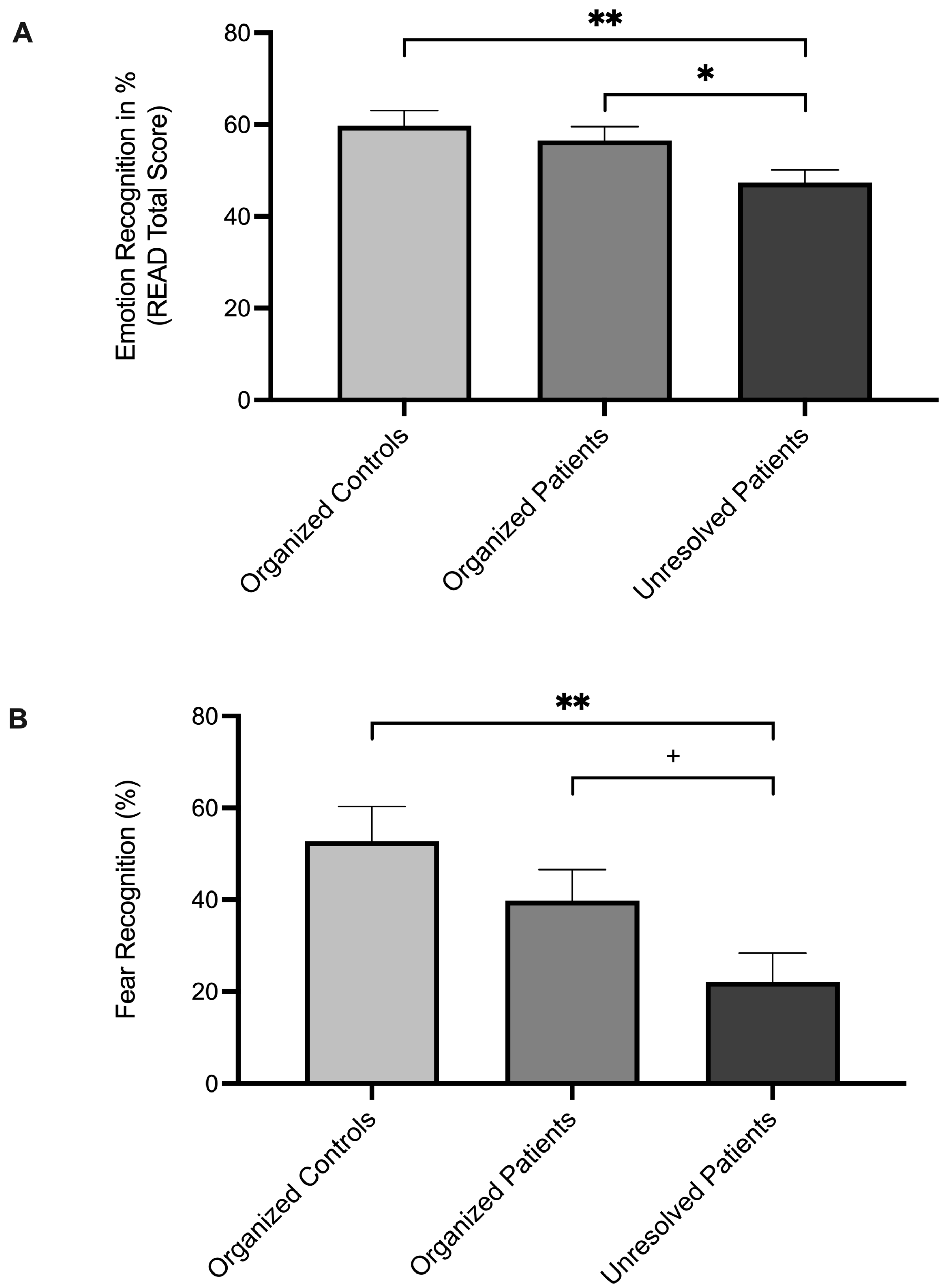

3.2.2. Interpersonal Emotion Perception: Emotion Recognition

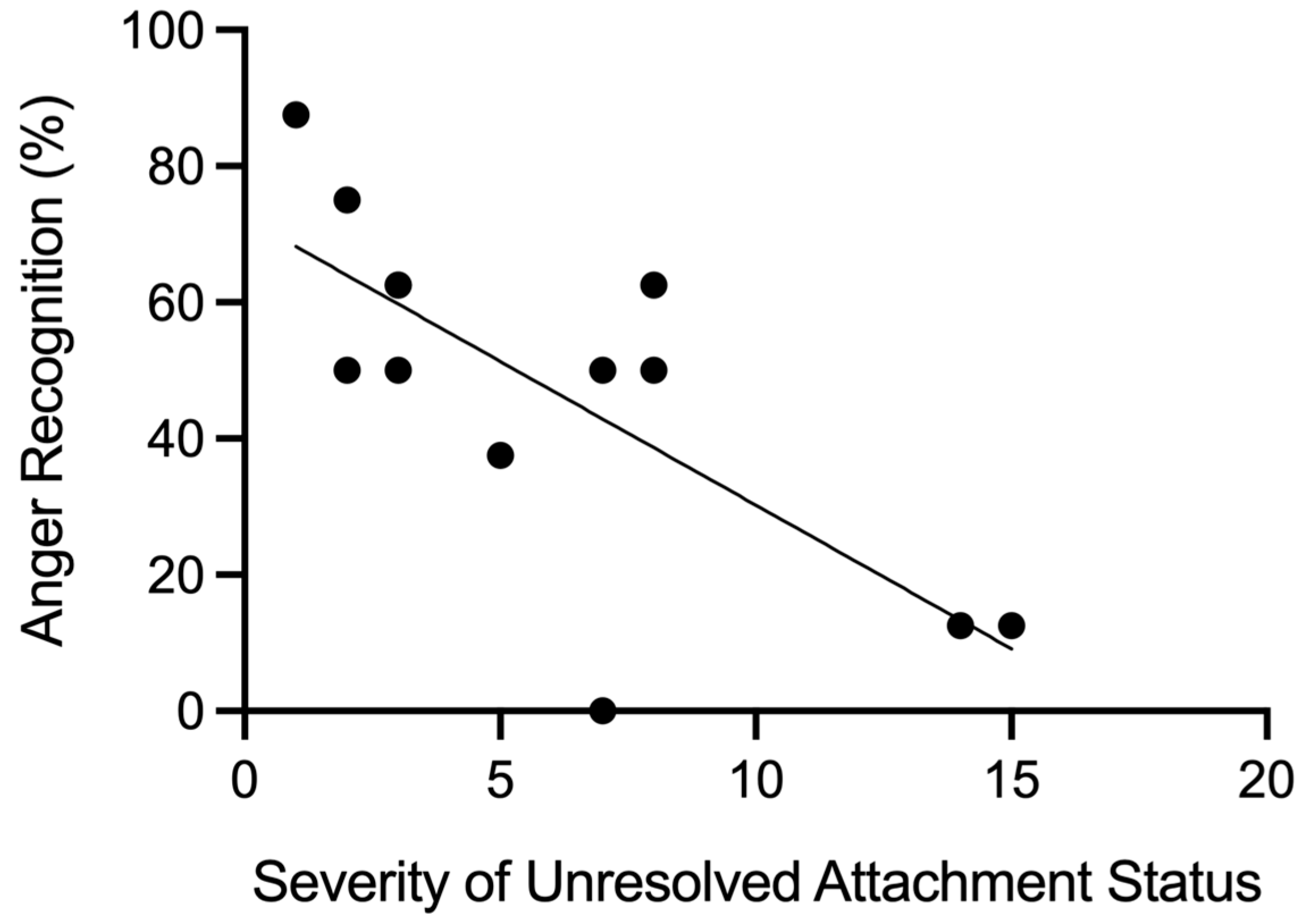

3.2.3. Severity of Unresolved Attachment Status and Fear and Anger Recognition

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Results

4.2. Theoretical Implications for Attachment Research

4.3. Practical Implications for Psychotherapy of Personality Disorders

4.4. Limitations and Methodological Considerations

4.5. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

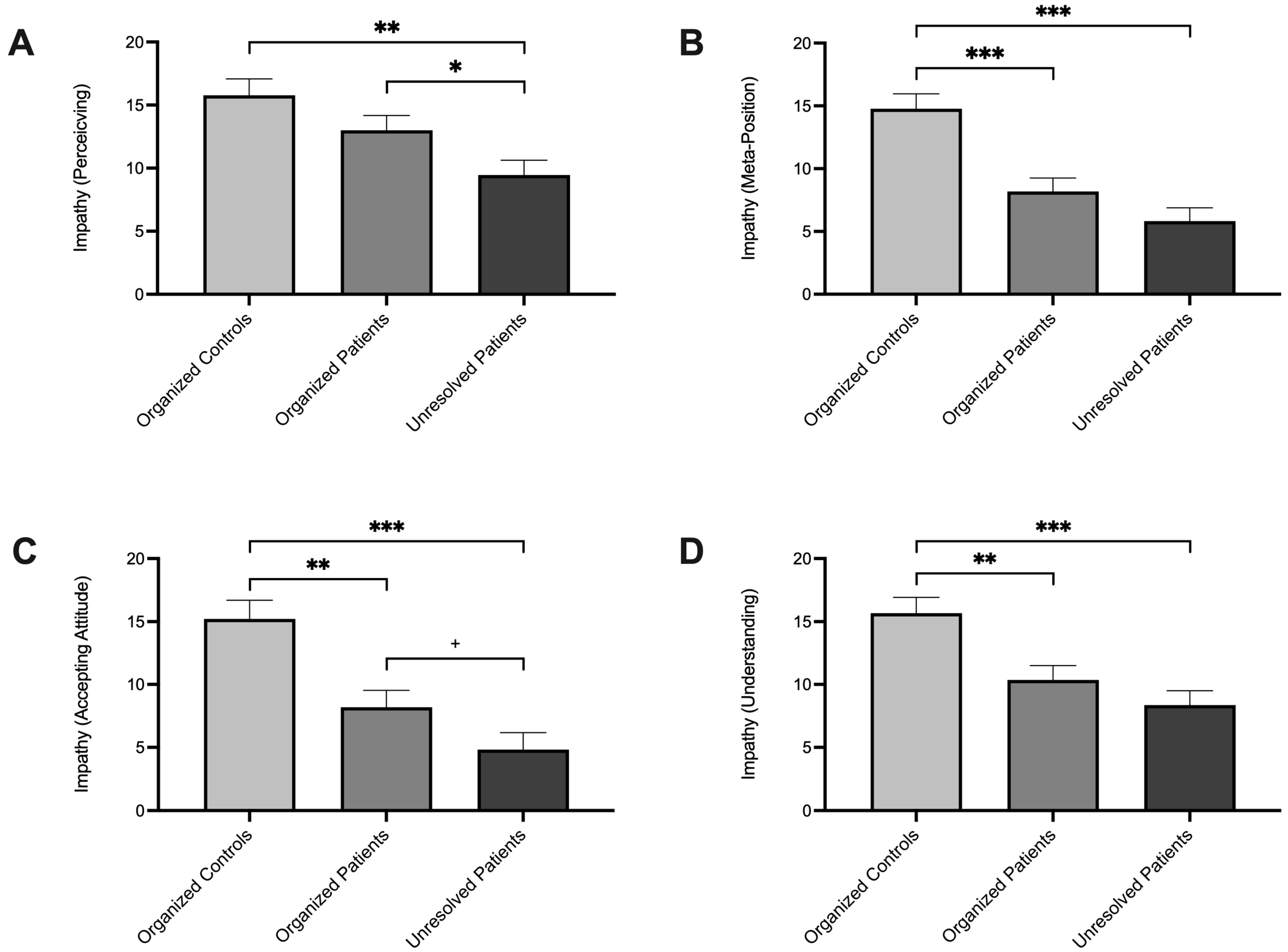

Appendix A. Group Comparisons on the Four Impathy Dimensions

References

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and Anger; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Vol. 3. Sadness and Depression; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base: Parent-Child Attachment and Healthy Human Development; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Eilert, D.W.; Buchheim, A. Attachment-Related Differences in Emotion Regulation in Adults: A Systematic Review on Attachment Representations. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kret, M.E.; Ploeger, A. Emotion processing deficits: A liability spectrum providing insight into comorbidity of mental disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 52, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, U.; Timulak, L. The emotional underpinnings of personality pathology: Implications for psychotherapy. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2022, 29, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjani, Z.; Mosanezhad Jeddi, E.; Hekmati, I.; Khalilzade, S.; Etemadi Nia, M.; Andalib, M.; Ashrafian, P. Comparison of Cognitive Empathy, Emotional Empathy, and Social Functioning in Different Age Groups. Aust. Psychol. 2020, 50, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmahl, C.; Herpertz, S.C.; Bertsch, K.; Ende, G.; Flor, H.; Kirsch, P.; Lis, S.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Rietschel, M.; Schneider, M.; et al. Mechanisms of disturbed emotion processing and social interaction in borderline personality disorder: State of knowledge and research agenda of the German Clinical Research Unit. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2014, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubrand, S.; Gaab, J. The missing construct: Impathy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 726029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubrand, S. The Missing Construct: Impathy—Conceptualization, Operationalization, and Clinical Considerations. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, G.J.; Bagby, R.M.; Kushner, S.C.; Benoit, D.; Atkinson, L. Alexithymia and adult attachment representations: Associations with the five-factor model of personality and perceived relationship adjustment. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1258–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, Y.; Wang, Y. The relationship between insecure attachment and alexithymia: A meta-analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 5804–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, I.K.; Taylor, A.M. Adult attachment styles and emotional regulation: The role of interoceptive awareness and alexithymia. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 173, 110641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wu, E.Z. The associations between self-compassion and adult attachment: A meta-analysis. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2024, 42, 681–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Ren, Y.; Song, X.; Ge, J.; Peng, Y. Insecure Attachment and Depressive Symptoms among a Large Sample of Chinese Young Adults: The Mediating Role of Positive and Negative Self-Compassion. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, N.; Cantin, M.; Barbeau, K.; Lavigne, G.; Lussier, Y. Self-Compassion as a Mediator of the Relationship between Adult Women’s Attachment and Intuitive Eating. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Steele, M.; Steele, H.; Moran, G.S.; Higgitt, A.C. The capacity for understanding mental states: The reflective self in parent and child and its significance for security of attachment. Infant Ment. Health J. 1991, 12, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Campbell, C.; Luyten, P. Attachment, Mentalizing and Trauma: Then (1992) and Now (2022). Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katznelson, H. Reflective functioning: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanske, P.; Böckler, A.; Trautwein, F.-M.; Parianen Lesemann, F.H.; Singer, T. Are strong empathizers better mentalizers? Evidence for independence and interaction between the routes of social cognition. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016, 11, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Babu, N. Cognitive and Affective Empathy in Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-analysis. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2023, 11, 756–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N.M.; van Reekum, C.M.; Chakrabarti, B. Cognitive and Affective Empathy Relate Differentially to Emotion Regulation. Affect. Sci. 2022, 3, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, H.; Steele, M.; Croft, C. Early attachment predicts emotion recognition at 6 and 11 years old. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2008, 10, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Blehar, M.C.; Waters, E.; Wall, S. Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation; Lawrence Erlbaum: Oxford, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Forslund, T.; Kenward, B.; Granqvist, P.; Gredeback, G.; Brocki, K.C. Diminished ability to identify facial emotional expressions in children with disorganized attachment representations. Dev. Sci. 2017, 20, e12465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallistl, M.; Kungl, M.; Gabler, S.; Kanske, P.; Vrticka, P.; Engert, V. Attachment and inter-individual differences in empathy, compassion, and theory of mind abilities. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2024, 26, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, I.; Calvo, V.; Grecucci, A. Attachment orientations and emotion regulation: New insights from the study of interpersonal emotion regulation strategies. Res. Psychother. 2023, 26, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, M.; Hesse, E. Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In Attachment in the Preschool Years: Theory, Research, and Intervention; The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation series on mental health and development; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Reisz, S.; Duschinsky, R.; Siegel, D.J. Disorganized attachment and defense: Exploring John Bowlby’s unpublished reflections. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2018, 20, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Fonagy, P.; Allen, J.; Strathearn, L. Mothers’ unresolved trauma blunts amygdala response to infant distress. Soc. Neurosci. 2014, 9, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.; West, M. The Adult Attachment Projective Picture System: Attachment Theory and Assessment in Adults; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gander, M.; Buchheim, A.; Kohlbock, G.; Sevecke, K. Unresolved attachment and identity diffusion in adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2025, 37, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, M.; Buchheim, A.; Sevecke, K. Personality Disorders and Attachment Trauma in Adolescent Patients with Psychiatric Disorders. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2024, 52, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, M.; Fuchs, M.; Franz, N.; Jahnke-Majorkovits, A.C.; Buchheim, A.; Bock, A.; Sevecke, K. Non-suicidal self-injury and attachment trauma in adolescent inpatients with psychiatric disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 2021, 111, 152273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichon, S.; de Gelder, B.; Grèzes, J. Two different faces of threat. Comparing the neural systems for recognizing fear and anger in dynamic body expressions. NeuroImage 2009, 47, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkin, J.F.; Caligor, E.; Stern, B.; Kernberg, O.F. Structured Interview of Personality Organization for Personality Disorder Evaluation and Treatment, TFP-NY. Available online: https://www.borderlinedisorders.com/structured-interview-of-personality-organization.php (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Franke, G.H. SCL-90®-S: Symptom Checklist-90®-Standard–Manual; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- George, C.; West, M. Adult Attachment Projective Picture System Protocol and Classification Scoring System (Version 8.1); Unpublished Manuscript; Mills College and University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eilert, D.W. Reliable Emotional Action Decoding Test (READ-49): Testdokumentation; Eilert-Akademie: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- George, C.; Kaplan, N.; Main, M. The Adult Attachment Interview; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Main, M.; Goldwyn, R. Adult Attachment Scoring and Classification System, Version 6.0; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gander, M.; Sevecke, K.; Buchheim, A. Disorder-specific attachment characteristics and experiences of childhood abuse and neglect in adolescents with anorexia nervosa and a major depressive episode. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2018, 25, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheim, A.; Erk, S.; George, C.; Kächele, H.; Kircher, T.; Martius, P.; Pokorny, D.; Ruchsow, M.; Spitzer, M.; Walter, H. Neural correlates of attachment trauma in borderline personality disorder: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 2008, 163, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, M.; Bouthillier, D.; Moss, E.; Rousseau, C.; Brunet, A. Emotion regulation strategies as mediators of the association between level of attachment security and PTSD symptoms following trauma in adulthood. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gander, M.; George, C.; Pokorny, D.; Buchheim, A. Assessing Attachment Representations in Adolescents: Discriminant Validation of the Adult Attachment Projective Picture System. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 48, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, C.; West, M. The development and preliminary validation of a new measure of adult attachment: The adult attachment projective. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2001, 3, 30–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchheim, A.; George, C. Attachment disorganization in borderline personality disorder and anxiety disorder. In Disorganization of Attachment and Caregiving; Solomon, J., George, V., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 343–383. [Google Scholar]

- Buchheim, A.; Erk, S.; George, C.; Kächele, H.; Martius, P.; Pokorny, D.; Spitzer, M.; Walter, H. Neural Response during the Activation of the Attachment System in Patients with Borderline Personality Disorder: An fMRI Study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergert, J.; Franke, G.; Petrowski, K. Erste Ergebnisse einer Äquivalenzprüfung zwischen SCL-90-S und SCL-90-R. In Proceedings of the 15. Nachwuchswissenschaftlerkonferenz Ost- und Mitteldeutscher Fachhochschulen, Magdeburg, Germany, 24 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, H.C.; Matsumoto, D. Facial Expressions. In APA Handbook of Nonverbal Communication; Matsumoto, D., Hwang, H.C., Frank, M.G., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 257–287. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, D.; Cordaro, D.T. Understanding Multimodal Emotional Expressions: Recent Advances in Basic Emotion Theory. In The Science of Facial Expression; Fernández-Dols, J.-M., Russell, J.A., Fernández-Dols, J.-M., Russell, J.A., Eds.; Oxford series in social cognition and social neuroscience; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, S.; ten Brinke, L. Reading Between the Lies. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D.; Hwang, H.C. Microexpressions Differentiate Truths From Lies About Future Malicious Intent. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, K.; Scherer, K.R. Introducing a short version of the Geneva Emotion Recognition Test (GERT-S): Psychometric properties and construct validation. Behav. Res. Methods 2016, 48, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, D. Erhebung und Analyse der Beziehungen zwischen der Emotionserkennungsfähigkeit. Master’s Thesis, SRH Fernhochschule Riedlingen, Riedlingen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bru-Luna, L.M.; Marti-Vilar, M.; Merino-Soto, C.; Cervera-Santiago, J.L. Emotional Intelligence Measures: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sageder, E. Emotionserkennungsfähigkeit im Vertrieb. Master’s Thesis, Danube Business School, Linz, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Scharff, N.-L. Inwieweit lässt sich die Emotionserkennungsfähigkeit von Verkäufern durch das Trainieren von Mikroexpressionen anhand eines Onlinetrainings steigern? Bachelor’s Thesis, Business School Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dorris, L.; Young, D.; Barlow, J.; Byrne, K.; Hoyle, R. Cognitive empathy across the lifespan. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 1524–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.E.; Voyer, D. Sex differences in the ability to recognise non-verbal displays of emotion: A meta-analysis. Cogn. Emot. 2014, 28, 1164–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feise, R.J. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2002, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourmohammad, P.; Imani, M.; Goodarzi, M.A.; Sarafraz, M.R. Impaired complex theory of mind and low emotional self-awareness in outpatients with borderline personality disorder compared to healthy controls: A cross-sectional study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 143, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Luyten, P. A developmental, mentalization-based approach to the understanding and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Dev. Psychopathol. 2009, 21, 1355–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliu-Soler, A.; Pascual, J.C.; Elices, M.; Martin-Blanco, A.; Carmona, C.; Cebolla, A.; Simon, V.; Soler, J. Fostering Self-Compassion and Loving-Kindness in Patients With Borderline Personality Disorder: A Randomized Pilot Study. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2017, 24, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayar, H.; Wilberg, T.; Eikenaes, I.U.; Ekberg, A.; Leitemo, K.; Morken, K.T.E.; Oftedal, E.; Omvik, S.; Ulvestad, D.A.; Pedersen, G.; et al. Improvement of alexithymia in patients treated in mental health services for personality disorders: A longitudinal, observational study. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1558654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, N.; Fonagy, P. Attachment and Personality Disorders: A Short Review. Focus 2013, 11, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riem, M.M.E.; van Hoof, M.J.; Garrett, A.S.; Rombouts, S.; van der Wee, N.J.A.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Vermeiren, R. General psychopathology factor and unresolved-disorganized attachment uniquely correlated to white matter integrity using diffusion tensor imaging. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 359, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, L.; Hackett, R.K.; Joubert, D. The association of unresolved attachment status and cognitive processes in maltreated adolescents. Child Abus. Rev. 2009, 18, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, M.; Solomon, J. Procedures for Identifying Infants as Disorganized/Disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In Attachment in the Preschool Years: Theory, Research, and Intervention; Greenberg, M.T., Cicchetti, D., Cummings, E.M., Eds.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1990; pp. 121–160. [Google Scholar]

- Rees, L.; Friedman, R.; Olekalns, M.; Lachowicz, M. Limiting fear and anger responses to anger expressions. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2020, 31, 581–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, S.; Eimontaite, I.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y. Fear, Anger, and Risk Preference Reversals: An Experimental Study on a Chinese Sample. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhao, D.; Wu, Y.; Tang, P.; Gu, R.; Luo, Y.J. Differentiating the influence of incidental anger and fear on risk decision-making. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 184, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, M.; Cassotti, M.; Moutier, S.; Houde, O.; Borst, G. Fear and anger have opposite effects on risk seeking in the gain frame. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, Z.; Dehghani, M.; Fathali Lavasani, F.; Farahani, H.; Ashouri, A. A network analysis of ICD-11 Complex PTSD, emotional processing, and dissociative experiences in the context of psychological trauma at different developmental stages. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1372620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlucci, L.; Saggino, A.; Balsamo, M. On the efficacy of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 87, 101999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiris, N.; Berle, D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Unified Protocol as a transdiagnostic emotion regulation based intervention. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 72, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saccaro, L.F.; Giff, A.; De Rossi, M.M.; Piguet, C. Interventions targeting emotion regulation: A systematic umbrella review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2024, 174, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neacsiu, A.D.; Tkachuck, M.A. Dialectical behavior therapy skills use and emotion dysregulation in personality disorders and psychopathy: A community self-report study. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2016, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, T.M.; Schulze, L.; Renneberg, B. The role of emotion regulation in the characterization, development and treatment of psychopathology. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 1, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripada, C.; Angstadt, M.; Taxali, A.; Kessler, D.; Greathouse, T.; Rutherford, S.; Clark, D.A.; Hyde, L.W.; Weigard, A.; Brislin, S.J.; et al. Widespread attenuating changes in brain connectivity associated with the general factor of psychopathology in 9- and 10-year olds. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, S.; Dixon-Gordon, K.L.; Turner, C.J.; Chen, S.X.; Chapman, A. Emotion Dysregulation in Personality Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2023, 25, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, A.; Delgadillo, J.; Barkham, M. Efficacy of personalized psychological interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 91, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.G.C.; Ringwald, W.R.; Hopwood, C.J.; Pincus, A.L. It’s time to replace the personality disorders with the interpersonal disorders. Am. Psychol. 2022, 77, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheim, A.; Horz-Sagstetter, S.; Doering, S.; Rentrop, M.; Schuster, P.; Buchheim, P.; Pokorny, D.; Fischer-Kern, M. Change of Unresolved Attachment in Borderline Personality Disorder: RCT Study of Transference-Focused Psychotherapy. Psychother. Psychosom. 2017, 86, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gander, M.; Karabatsiakis, A.; Nuderscher, K.; Bernheim, D.; Doyen-Waldecker, C.; Buchheim, A. Secure Attachment Representation in Adolescence Buffers Heart-Rate Reactivity in Response to Attachment-Related Stressors. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 806987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchheim, A.; Labek, K.; Taubner, S.; Kessler, H.; Pokorny, D.; Kachele, H.; Cierpka, M.; Roth, G.; Pogarell, O.; Karch, S. Modulation of Gamma Band Activity and Late Positive Potential in Patients with Chronic Depression after Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. Psychother. Psychosom. 2018, 87, 252–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchheim, A.; Gander, M. Clinical and neurobiological applications of the AAP in adults and adolescents: Therapeutic implications. In Working with Attachment Trauma: Clinical Application of the Adult Attachment Projective Picture System; George, C., Aikins, J.W., Lehmann, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, A.; Fonagy, P.; Campbell, C.; Luyten, P.; Debbané, M. Cambridge Guide to Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Clarkin, J.F.; Yeomans, F.E.; Kernberg, O.F. Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality: Focusing on Object Relations.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Neff, K.D. Self-Compassion: Theory, Method, Research, and Intervention. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Z.-T.; Lin, C.-L. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Intervention and Emotional Recovery in Borderline Personality Features: Evidence from Psychophysiological Assessment. Mindfulness 2022, 13, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, L.F.; Coifman, K.G.; Rafaeli, E.; Berenson, K.R.; Downey, G. Emotion differentiation as a protective factor against nonsuicidal self-injury in borderline personality disorder. Behav. Ther. 2013, 44, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farashi, S.; Bashirian, S.; Jenabi, E.; Razjouyan, K. Effectiveness of virtual reality and computerized training programs for enhancing emotion recognition in people with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2024, 70, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenske, S.; Lis, S.; Liebke, L.; Niedtfeld, I.; Kirsch, P.; Mier, D. Emotion recognition in borderline personality disorder: Effects of emotional information on negative bias. Borderline Personal. Disord. Emot. Dysregul. 2015, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D.; Hwang, H.C. Facial Expressions. In Nonverbal Communication: Science and Applications; Matsumoto, D., Frank, M.G., Hwang, H.C., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Patients | Controls | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), M (SD) | 21.33 (2.35) | 22.00 (1.32) | 21.52 (2.12) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 15 (62.5) | 8 (88.9) | 23 (69.7) |

| Male | 8 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | 9 (27.3) |

| Non-binary | 1 (4.2) | – | 1 (3.0) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 19 (79.2) | 6 (66.7) | 25 (75.8) |

| Married | 2 (8.3) | – | 2 (6.0) |

| Long-term relationship | 3 (12.5) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (18.2) |

| Level of education, n (%) | |||

| No compulsory schooling | 1 (4.2) | – | 1 (3.0) |

| Compulsory schooling | 12 (50.0) | – | 12 (36.4) |

| Apprenticeship | 2 (8.3) | – | 2 (6.0) |

| Technical/commercial school | 1 (4.2) | – | 1 (3.0) |

| University entrance qualification | 6 (25.0) | 6 (66.7) | 12 (36.4) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 2 (8.3) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (15.2) |

| Country of origin, n (%) | |||

| Austria | 19 (79.2) | – | 19 (57.6) |

| Germany | 2 (8.3) | 8 (88.9) | 10 (30.4) |

| Other | 3 (12.5) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (12.0) |

| Attachment Representation, n (%) | |||

| Organized | 11 (45.8) | 9 (100.0) | 20 (60.6) |

| Unresolved | 13 (54.2) | – | 13 (39.4) |

| Unresolved Trauma Markers, M (SD) | 3.25 (4.45) | 0 (0) | 2.36 (4.05) |

| SCL-90-S (GSI), M (SD) | 1.71 (0.61) | 0.35 (0.09) | 1.34 (0.80) |

| Measure/Dimension | Organized Controls n = 9 | Organized Patients n = 11 | Unresolved Patients n = 13 1 | General Linear Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impathy Inventory, M (SD) | 61.44 (8.28) a | 39.73 (16.16) b | 28.45 (14.74) b | F1, 28 = 14.39, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.51 * |

| Perceiving | 15.78 (2.64) a | 13.00 (4.22) a | 9.45 (4.30) b | F1, 28 = 6.74, p = 0.004, η2p = 0.33 * |

| Meta-Position | 14.78 (3.31) a | 8.18 (3.40) b | 5.82 (3.87) b | F1, 28 = 16.55, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.54 * |

| Accepting Attitude | 15.22 (1.92) a | 8.18 (5.72) b | 4.82 (4.49) b | F1, 28 = 13.73, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.50 * |

| Understanding | 15.67 (2.65) a | 10.36 (4.54) b | 8.36 (3.67) b | F1, 28 = 9.72, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.41 * |

| READ-64, M (SD) | 59.72 (9.17) a | 56.54 (12.06) a | 47.36 (8.71) b | F1, 30 = 4.63, p = 0.02, η2p = 0.24 * |

| Fear | 52.78 (28.49) a | 39.77 (20.78) a,b | 22.12 (19.20) b | F1, 30 = 5.11, p = 0.01, η2p = 0.25 * |

| Surprise | 82.10 (18.92) a | 85.23 (23.60) a | 84.62 (18.51) a | F1, 30 = 0.06, p = 0.94, η2p = 0.00 |

| Anger | 66.67 (13.98) a | 55.68 (25.84) a | 47.12 (25.59) a | F1, 30 = 1.90, p = 0.17, η2p = 0.11 |

| Disgust | 43.06 (30.69) a | 59.09 (30.15) a | 40.93 (23.80) a | F1, 30 = 1.42, p = 0.26, η2p = 0.09 |

| Contempt | 44.44 (27.32) a | 44.32 (29.24) a | 33.65 (25.20) a | F1, 30 = 0.61, p = 0.55, η2p = 0.04 |

| Sadness | 65.28 (19.54) a | 57.60 (23.23) a | 43.30 (30.45) a | F1, 30 = 2.15, p = 0.13, η2p = 0.13 |

| Happiness | 56.35 (25.00) a | 39.77 (31.53) a | 44.23 (27.77) a | F1, 30 = 0.89, p = 0.42, η2p = 0.06 |

| Social Smile | 66.67 (25.00) a | 70.46 (27.54) a | 63.25 (25.09) a | F1, 30 = 0.23, p = 0.80, η2p = 0.02 |

| SCL-90-S (GSI), M (SD) | 0.35 (0.09) a | 1.52 (0.58) b | 1.86 (0.61) b | F1, 30 = 24.17, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.62 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eilert, D.W.; de Punder, K.; Maerz, J.; Dose, J.; Gander, M.; Mensah, P.; Neubrand, S.; Hinterhölzl, J.; Buchheim, A. Impathy and Emotion Recognition: How Attachment Shapes Self- and Other-Focused Emotion Processing. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15050516

Eilert DW, de Punder K, Maerz J, Dose J, Gander M, Mensah P, Neubrand S, Hinterhölzl J, Buchheim A. Impathy and Emotion Recognition: How Attachment Shapes Self- and Other-Focused Emotion Processing. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(5):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15050516

Chicago/Turabian StyleEilert, Dirk W., Karin de Punder, Jeff Maerz, Johanna Dose, Manuela Gander, Philipp Mensah, Stefanie Neubrand, Josef Hinterhölzl, and Anna Buchheim. 2025. "Impathy and Emotion Recognition: How Attachment Shapes Self- and Other-Focused Emotion Processing" Brain Sciences 15, no. 5: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15050516

APA StyleEilert, D. W., de Punder, K., Maerz, J., Dose, J., Gander, M., Mensah, P., Neubrand, S., Hinterhölzl, J., & Buchheim, A. (2025). Impathy and Emotion Recognition: How Attachment Shapes Self- and Other-Focused Emotion Processing. Brain Sciences, 15(5), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15050516