Abstract

Objective: Caregivers of individuals with motor neurone disease (MND) face a wide range of psychosocial difficulties. To address these, non-pharmacological interventions have been trialled, showing promising results. However, no clear characterisation of the breadth of psychosocial constructs examined by the interventions is currently available, resulting in the lack of a core outcome set (COS). The present review explored the types of psychosocial outcomes investigated in studies that adopted non-pharmacological interventions with caregivers of people with MND. Methods: A scoping review was conducted across four major databases (Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and MEDLINE) from inception to the 1 March 2024. Results: From an initial return of 4802 citations, 10 were considered eligible for inclusion. A total of 10 main psychosocial outcomes were identified: anxiety and depression, psychological distress, resilience, caregiver burden, caregiver preparedness, self-efficacy, quality of life, spiritual wellbeing, and mindfulness. Conclusions: Caregiver burden and symptoms of anxiety and depression represent pivotal outcomes, but caution is advised with regard to caregiver burden’s potential multidimensional structure. Psychological distress and quality of life are also commonly investigated, but clearer consensus is needed on their conceptualisation. There is a paucity of studies characterising important psychosocial outcomes such as resilience, problem-solving, self-efficacy, and mindfulness, while no investigations are available for relevant outcomes such as coping, isolation, and loneliness. Further research is warranted to address these gaps to improve our insight into non-pharmacological support for MND caregivers and ultimately lead to the development of a core psychosocial outcome set in this population.

1. Introduction

Motor neurone disease (MND), also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), is a progressive neurological disorder characterised by the degeneration of upper and/or lower motor neurones. It causes progressive paralysis and consequent difficulties with movement, speech, swallowing, and breathing [1,2] and is considered to be on a spectrum with frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [3,4]. Psychological difficulties are common in people with MND (pwMND), with evidence indicating that up to 44% of individuals experience depression and up to 30% experience anxiety directly attributed to their experience of living with MND [5]. Currently, no cure is available for MND, and palliative care represents the mainstay of its clinical management [6].

As the disease progresses, pwMND often face increasing struggles with mobility, personal care, and other activities of daily living (ADLs), ultimately leading to a need for continuous care [7]. This is frequently provided by informal caregivers, namely family members or friends [8], and involves support with ADLs such as eating, bathing, taking medication, and mobilising [9]. These can exert a significant toll on caregivers’ wellbeing, physically (e.g., moving wheelchairs or hoisting and transferring) and emotionally (e.g., witnessing deterioration in their loved one or discussing end-of-life care) [10,11]. Many caregivers experience marked role changes related to carrying out activities that were once the responsibility of their partner/relative (e.g., cooking, driving) [10,12]. Moreover, since the progression of MND can be rapid and unpredictable [13,14], caregivers often need to adjust to changes within a very short period of time, leaving them feeling unable to live their lives as before [15].

As such, caregivers frequently face psychosocial difficulties [10,16], defined as issues produced by social, occupational, or environmental circumstances (e.g., isolation) that affect psychological wellbeing [17]. Indeed, MND caregivers often experience high levels of depression, anxiety, and grief [18], as well as reduced communication, increased loneliness and helplessness, and decreased sense of self [19,20]. These issues have been shown to be more severe in caregivers of pwMND than those for other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis [21]. Caregiver wellbeing is often crucial for the wellbeing of pwMND since bidirectional relationships between the emotional wellbeing of both parties have been identified [9,22]. Additionally, caregiving capacity can be a deciding factor in whether pwMND remain at home or enter a care facility [9,10,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

To address psychosocial difficulties, non-pharmacological interventions have been trialled with MND caregivers. For instance, a mixed-methods systematic review [24] identified several interventions targeting psychological wellbeing in caregivers of pwMND, including self-management, mindfulness, dignity therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), and person-centred therapy. The results found that, while a few studies yielded promising results with regard to psychosocial outcomes, a wide range of methodological issues prevented their generalisability. More recently, Oh and colleagues [25] carried out a scoping review of psychosocial interventions for both pwMND and their caregivers, identifying 25 studies exploring approaches, such as social support, mindfulness, behavioural therapy, and education programmes. Based on both quantitative and qualitative investigations, the authors concluded that the feasibility and acceptability of such interventions appear promising. However, similarly to the previous review [24], several methodological issues, such as high dropout rates, small sample sizes, and lack of randomisation, severely limited the generalisability of these findings to the overall MND caregiver population.

Whilst issues around the heterogeneity and validity of outcomes were raised by both reviews [24,25], neither provided a focused and systematic characterisation of the breadth of psychosocial constructs examined by the interventions. This represents a considerable gap in the current literature, as clarity about outcomes is a crucial part of evaluating interventions [26]. As reported with individuals affected by other chronic conditions as shown with other chronic conditions [27,28], obtaining specific insight into the outcomes adopted by previous studies can allow for the development of core outcome sets (COSs) to inform new treatment approaches.

Therefore, the overarching aim of the present review was to explore and map the range of psychosocial outcomes investigated to date in studies which adopted non-pharmacological interventions with caregivers of pwMND. More specifically, unlike the previous recent reviews [24,25], this work did not focus on the results and efficacy of non-behavioural interventions but rather addressed the types of outcomes included in these investigations and the way these were operationalised by addressing the following review question: what psychosocial outcomes have been investigated in non-pharmacological interventions for caregivers of people with motor neurone disease and with what measures?

2. Method

2.1. Design

A scoping review was conducted based on the latest guidelines by the Joanna Briggs Institute [29]. This design was adopted due to its usefulness in mapping specific elements within a body of literature characterised by paucity and heterogeneity of evidence while also retaining a systematic and replicable approach [30].

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

To be included, studies had to (a) be related to individuals caring informally for a person with a clinically confirmed diagnosis of MND/ALS; (b) describe the delivery of any non-pharmacological intervention where psychosocial constructs were formally assessed as primary or secondary outcomes with a quantitative measure; and (c) feature a formal comparison within-group or between-groups (e.g., with the control group). For this review, psychosocial outcomes were conceived as the target outcomes of interventions which are non-pharmacological and non-surgical in nature and designed to affect individuals’ decisions and actions decisions around their health and wellbeing [31,32]. Table 1 illustrates the PICO(S) framework for the inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

PICO(S) framework.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Studies not related to informal caregivers of people with MND, non-interventional and qualitative designs, and studies with no formal comparisons were excluded. Reviews, commentaries, letters to editors, conference proceedings, grey literature, and studies not fully published in English were also not included. These criteria were adopted to avoid including data which were irrelevant (e.g., not involving caregivers) or insufficiently characterised for the aims of this review (e.g., commentaries and conference proceedings).

2.4. Quality Assessment

Due to the heterogeneity of outcome conceptualisations, and in line with the latest guidance on scoping reviews [33], a formal quality appraisal of the evidence was not performed in this review. However, methodological limitations of some of the measures adopted in the included studies were discussed where relevant.

2.5. Procedure

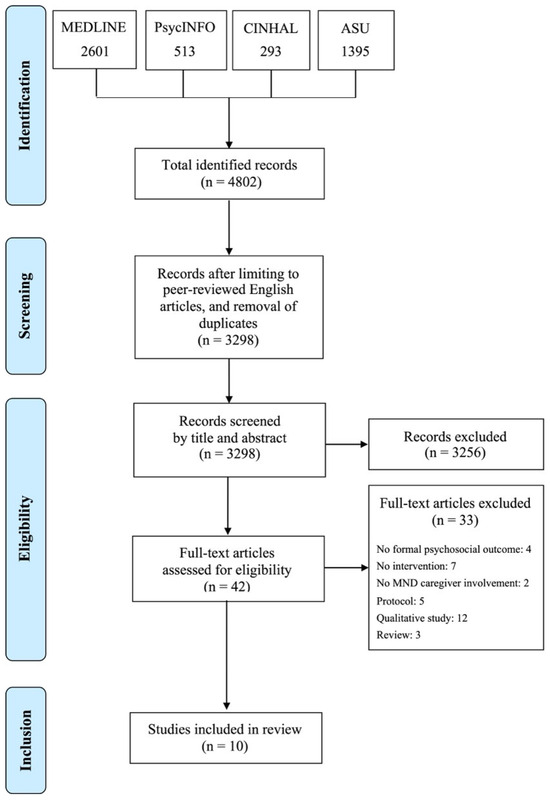

A combination of free text terms and Boolean operators were adopted to search four major databases from inception to the 1 March 2024: Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and MEDLINE. Reference lists of included studies were hand-searched. Table 1 shows the logic grid for the search strategy, while Table 2 illustrates the adopted search terms. Initially, two reviewers (C.O. and L.M.) screened all titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria, which were then checked by a further three reviewers (N.Z., S.M.M., and C.C.). Following the initial screening, the full texts of the remaining citations were inspected by two reviewers (C.O. and L.M.) and confirmed by three other reviewers (N.Z., S.M.M., and C.C.). Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection.

Table 2.

Logic grid for the search strategy.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for selection of studies.

2.6. Protocol Registration

Since scoping reviews are currently not accepted by the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO), no formal registration was carried out for the protocol of the present review.

3. Results

The database searches yielded a total of 4802 citations, which was reduced to 3298 citations following de-duplication. Screening based on title and abstract led to the exclusion of 3261 papers, leaving 37 full-text citations to be considered for inclusion. After full-text screening, 10 papers were considered eligible for the review. Table 3 illustrates the main characteristics of the included studies. The list of citations excluded following full-text screening is available as Supplementary Materials. Due to this review’s specific focus on the breadth, conceptualisation, and measurement of outcomes, the characteristics of the participants, as well as the results of the interventions in terms of efficacy in each study, are not reported below. However, a brief summary of these has been included in Table 4 to help contextualise the present findings.

Table 3.

Adopted search terms.

Table 4.

Key characteristics of included studies.

Of the ten included studies, six were interventions designed specifically for MND caregivers [34,35,36,37,38,39], whereas four studies included both MND patients and caregivers [40,41,42,43]. The outcomes investigated by the interventions are reported below. Higher levels of evidence hierarchy, such as randomised controlled trials (RCTs), are highlighted when appropriate.

3.1. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms

Due to the high rate of co-investigation of symptoms of depression and anxiety both as constructs as well as across single measure tools (e.g., HADS), these have been grouped together in the present review.

Five studies investigated symptoms of anxiety and depression in MND caregivers [34,36,38,40,42]. Two of these [36,42] were RCTs. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [44] was the most adopted measure, featuring four studies [34,36,40,42]. The remaining citation [38] adopted the Brief Profile of Mood States (POMS) [45] and the 10-item Centre for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CES–D) [46].

3.2. Psychological Distress

Psychological distress constructs—such as grief, hopelessness, and stress—were investigated by four studies [34,37,38,39]. Of these, one was an RCT [37], which adopted the Italian version of the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [47]. The remaining three citations, all pre–post designs [34,38,39], adopted the Brief Symptom Inventory 18 (BSI-18) [48], the Herth Hope Index (HHI) [49], and the 12-item Prolonged Grief Scale (PG-12) [50], which assesses feelings of grief leading up to an expected death.

3.3. Resilience

One RCT [37] investigated resilience in MND caregivers adopting the Connor Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [51], a measure which explores an individual’s ability to bounce back following adverse life events.

3.4. Caregiver Burden

Caregiver burden, which has been defined as the “level of multifaceted strain perceived by the caregiver from caring for a family member and/or loved one over time” [52], was investigated as an outcome by nine studies [34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. Of these, five [36,37,41,42,43] were RCTs. The most frequently adopted measure was the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) [53], featuring four studies [34,36,40,42]. Other adopted measures included the Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) [54], the Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) [55], and the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI) [56].

3.5. Caregiver Preparedness

Caregiver preparedness was investigated by one study based on a pre–post design [39] and adopting the Preparedness for Caregiving Scale [57].

3.6. Problem-Solving

A pilot pre–post study [39] explored caregivers’ perceived problem-solving skills with the Problem Solving Inventory (PSI) [58].

3.7. Self-Efficacy

One pre–post study [35] adopted exploratory ad hoc items to assess caregivers’ self-efficacy and feelings of goal attainment across a range of different caregiving activities (e.g., meal preparation, toileting, and administering medication) measured with a modified young carers version of the Multidimensional Assessment of Caring Activities (MACA-YC18).

3.8. Quality of Life

The quality of life of MND caregivers was investigated as an outcome of four studies [36,38,42,43]. These included three RCTs [36,42,43], which adopted the Mental Component Summary Score of the Medical Outcomes Study Questionnaire Short Form 36 (SF-36-MCS) [59]. Other measures included the McGill’s Quality of Life Questionnaire [60] and the Quality of Life at the End of Life (QUAL-E) [61].

3.9. Spiritual Wellbeing

Caregivers’ spiritual wellbeing was explored as an outcome in a pre–post study [38] using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp), which measures a sense of meaning and the role of faith in experiencing a long-term illness [62], and the Brief Religious Coping Activity Scales (RCOPE) [63], which focuses on positive and negative religious coping styles.

3.10. Mindfulness

Only one pre–post study [39] investigated caregivers’ levels of mindfulness by using the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale—Revised (CAMS-R) [64].

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

This scoping review aimed to map the breadth of psychosocial outcomes which have been investigated by non-pharmacological interventions involving caregivers of pwMND. To our knowledge, this is the first review to explore this area. From an initial return of 4802 citations, 10 were eventually considered eligible for inclusion in the review. Half of these studies were RCTs [36,37,41,42,43], while the other five adopted a pre–post design [34,35,38,39,40]. A total of 10 main psychosocial outcomes were identified in the included studies: anxiety and depression symptoms, psychological distress, resilience, caregiver burden, caregiver preparedness, problem-solving, self-efficacy, quality of life, spiritual wellbeing, and mindfulness.

Caregiver burden was the most frequent outcome, being investigated by nine studies out of ten [34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. This was mostly measured with the ZBI [53], a self-report questionnaire with a long history of adoption not only with caregivers of individuals with MND [8] but also with other neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s [65,66], Parkinson’s [67,68], and Huntington’s [69,70]. However, a factor analysis of the ZBI carried out with MND family caregivers highlighted a 3-factor structure encompassing social restrictions, self-criticism, and anger and frustration [71]—suggesting that interventions may need to consider a multifactorial view of caregiver burden when planning interventions in this population.

The second most frequent psychosocial outcome was represented by symptoms of anxiety and depression, which were investigated by half of the included studies [34,36,38,39,40]. This is perhaps unsurprising since these issues have been shown to be prevalent among MND caregivers [72,73] and related to increased burden, lower quality of life, and higher risk of health problems [74,75]. The most adopted measure of anxiety and depression symptoms was the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [44]—a finding that mirrors a previous systematic review which identified the HADS among the most frequent measures across cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of caregiver burden in MND [8].

Four studies investigated psychological distress [34,37,38,39] and quality of life [36,38,42,43], making them the third most common psychosocial outcome. Similarly to symptoms of anxiety and depression, both constructs have often been the focus of studies involving MND caregivers [75,76,77]. However, the wide range of measures observed in this review suggests that their conceptualisation may vary considerably across researchers, with some authors focusing on specific aspects such as grief, hopelessness, or end of life [34,38,40], while others explored more general forms of stress or quality of life [36,39,42,43].

The remaining six psychosocial outcomes—resilience, caregiver preparedness, problem-solving, self-efficacy, spiritual wellbeing, and mindfulness—were investigated only by one study each. While constructs such as spirituality have not frequently been the object of exploration in MND caregivers [78], the paucity of studies investigating resilience, mindfulness, problem-solving, and self-efficacy as intervention outcomes, represents a more unexpected finding, particularly considering the significant attention they have received in non-interventional studies with this population [79,80,81,82,83,84]. Perhaps even more surprising was that one of the two mindfulness-based interventions in this review did not include a measure of mindfulness among its outcomes [36]. In addition, no studies were identified for other psychosocial outcomes such as (non-religious) coping, isolation, and loneliness—all of which have been previously highlighted as pivotal in MND caregivers [85,86,87].

4.2. Implications for Future Interventions

The findings of the present review show a number of important implications for the future development of non-pharmacological interventions for MND caregivers, and the conceptualisation and evaluation of a future core psychosocial outcome set. First, caregiver burden and difficulties related to anxiety and depression were identified as the most common outcomes across all studies, highlighting that their operationalisation is likely to represent a crucial part of an outcome set. However, caution should be advised when operationalising caregiver burden as a unifactorial construct, as evidence has suggested a potential multidimensional structure in widely adopted measures such as the ZBI. Thus, future studies should aim to explore this outcome in a more multifaceted fashion, potentially adopting a more comprehensive set of measures.

Secondly, while the findings of this review highlighted psychological distress and quality of life as important outcomes for non-pharmacological interventions for MND caregivers, the high level of variability in how such constructs are conceptualised by researchers (as well as caregivers themselves) should be considered. Therefore, a clearer consensus is needed on the operationalisation of psychological distress and quality of life in this population, and future interventions would benefit from including more comprehensive descriptions and rationales for adopting specific measures.

Finally, our findings highlighted a severe paucity of intervention studies assessing important psychosocial outcomes such as resilience, problem-solving, self-efficacy, and mindfulness, even when they represented the core of specific interventions. Further investigations are therefore warranted to address these in MND caregivers, along with other relevant outcomes for which no studies were identified in the present review, such as coping, isolation, and loneliness.

4.3. Limitations

A number of limitations should be considered with the present findings. First, while they allow to map of emerging studies characterised by a paucity of studies, scoping reviews provide preliminary overviews which preclude more definite clinical recommendations and should thus be followed by systematic reviews as additional evidence accrues. Secondly, issues such as conceptual diversity and overlapping for some constructs and outcomes (e.g., psychological distress and quality of life) represent a further limitation and future studies should aim to work towards reaching a consensus on this matter. Finally, all the eligible studies in this review were carried out in Western countries and may limit the value of the implications of this review across different settings. Further investigations are therefore needed involving MND caregivers in under-represented countries and cultures.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review shed new light on the current conceptualisation and operationalisation of psychosocial outcomes in non-pharmacological interventions for MND caregivers. Caregiver burden symptoms of anxiety and depression appear to be pivotal outcomes, but caregiver burden should be explored as a multifaceted construct. Psychological distress and quality of life are also important, but their conceptualisation varies greatly, necessitating a clearer consensus among researchers. Nonetheless, important psychosocial outcomes such as resilience, problem-solving, self-efficacy, and mindfulness have received considerably less attention in this population. Further intervention studies are warranted to address these gaps and consider other relevant outcomes such as coping, isolation, and loneliness to improve our insight into non-pharmacological support for MND caregivers and ultimately lead to the development of a core psychosocial outcome set.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/brainsci15020112/s1, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist. Reference [88] is cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.O., L.M., S.M.M., C.C. and N.Z.; Methodology, C.O., L.M., S.M.M., C.C. and N.Z.; Software, N.Z.; Formal Analysis, C.O., L.M., S.M.M., C.C. and N.Z.; Investigation, N.Z.; Data Curation, C.O. and L.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.O. and L.M.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.O., L.M., S.M.M., C.C. and N.Z.; Supervision, S.M.M., C.C. and N.Z.; Project Administration, N.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Abrahams, S. ALS, Cognition and the Clinic. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2013, 14, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukan, J.; Elamin, M.; Bede, P.; Jordan, N.; Gallagher, L.; Byrne, S.; Lynch, C.; Pender, N.; Hardiman, O. The Syndrome of Cognitive Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Population-Based Study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 2012, 83, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxon, J.A.; Thompson, J.C.; Harris, J.M.; Richardson, A.M.; Langheinrich, T.; Rollinson, S.; Pickering-Brown, S.; Chaouch, A.; Ealing, J.; Hamdalla, H.; et al. Cognition and Behaviour in Frontotemporal Dementia with and without Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, M.J.; Abrahams, S.; Goldstein, L.H.; Woolley, S.; Mclaughlin, P.; Snowden, J.; Mioshi, E.; Roberts-South, A.; Benatar, M.; HortobáGyi, T.; et al. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis—Frontotemporal Spectrum Disorder (ALS-FTSD): Revised Diagnostic Criteria. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2017, 18, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurt, A.; Nijboer, F.; Matuz, T.; Kübler, A. Depression and Anxiety in Individuals with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2007, 21, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.; Eccles, F.J.; Zarotti, N. Extended Evidence-Based Guidance on Psychological Interventions for Psychological Difficulties in Individuals with Huntington’s Disease. In Parkinson’s Disease, Motor Neurone Disease, and Multiple Sclerosis; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Krivickas, L.S.; Shockley, L.; Mitsumoto, H. Home Care of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). J. Neurol. Sci. 1997, 152, S82–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit, J.; Bakker, L.A.; van Groenestijn, A.C.; van den Berg, L.H.; Schröder, C.D.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; Beelen, A. Caregiver Burden in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiò, A.; Gauthier, A.; Calvo, A.; Ghiglione, P.; Mutani, R. Caregiver Burden and Patients’ Perception of Being a Burden in ALS. Neurology 2005, 64, 1780–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, S.K.; Baird, W.O.; Thompson, S.; Bianchi, S.M.; Walters, S.J.; Lee, E.; Ahmedzai, S.H.; Proctor, A.; Shaw, P.J.; McDermott, C.J. The Impact on the Family Carer of Motor Neurone Disease and Intervention with Noninvasive Ventilation. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 1602–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velaga, V.C.; Cook, A.; Auret, K.; Jenkins, T.; Thomas, G.; Aoun, S.M. Palliative and End-of-Life Care for People Living with Motor Neurone Disease: Ongoing Challenges and Necessity for Shifting Directions. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, E.; Zarotti, N.; Williams, I.; White, S.; Halliday, V.; Beever, D.; Hackney, G.; Stavroulakis, T.; White, D.; Norman, P.; et al. Patient, Carer and Healthcare Professional Perspectives on Increasing Calorie Intake in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Chronic Illn. 2021, 19, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarotti, N.; Coates, E.; McGeachan, A.; Williams, I.; Beever, D.; Hackney, G.; Norman, P.; Stavroulakis, T.; White, D.; White, S.; et al. Health Care Professionals’ Views on Psychological Factors Affecting Nutritional Behaviour in People with Motor Neuron Disease: A Thematic Analysis. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, V.; Zarotti, N.; Coates, E.; McGeachan, A.; Williams, I.; White, S.; Beever, D.; Norman, P.; Gonzalez, S.; Hackney, G.; et al. Delivery of Nutritional Management Services to People with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2021, 22, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, É.; Kennedy, P.; Heverin, M.; Leroi, I.; Mayberry, E.; Beelen, A.; Stavroulakis, T.; van den Berg, L.H.; McDermott, C.J.; Hardiman, O.; et al. Informal Caregivers in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Multi-centre, Exploratory Study of Burden and Difficulties. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, S.M.; Bentley, B.; Funk, L.; Toye, C.; Grande, G.; Stajduhar, K.J. A 10-Year Literature Review of Family Caregiving for Motor Neurone Disease: Moving from Caregiver Burden Studies to Palliative Care Interventions. Palliat. Med. 2013, 27, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.Y.; Lin, C.W.; Lin, M.J.; Wen, C.C. Psychosocial Issues Discovered through Reflective Group Dialogue between Medical Students. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, A.; Vignola, A.; Calvo, A.; Cavallo, E.; Moglia, C.; Sellitti, L.; Mutani, R.; Chiò, A. A Longitudinal Study on Quality of Life and Depression in ALS Patient-Caregiver Couples. Neurology 2007, 68, 923–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.; Geraghty, A.W.A.; Yardley, L.; Dennison, L. Emotional Distress and Well-Being among People with Motor Neurone Disease (MND) and Their Family Caregivers: A Qualitative Interview Study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Xue, H.; Li, L.; Tang, S. Caregivers of ALS Patients: Their Experiences and Needs. Neuroethics 2024, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.P.; Firth, L.; O’Connor, E. A Comparison of Mood and Quality of Life among People with Progressive Neurological Illnesses and Their Caregivers. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2009, 16, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabkin, J.G.; Wagner, G.J.; del Bene, M. Resilience and Distress Among Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients and Caregivers. Psychosom. Med. 2000, 62, 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Goutman, S.A.; Nowacek, D.G.; Burke, J.F.; Kerber, K.A.; Skolarus, L.E.; Callaghan, B.C. Minorities, Men, and Unmarried Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients Are More Likely to Die in an Acute Care Facility. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2014, 15, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cafarella, P.; Effing, T.; Chur-Hansen, A. Interventions Targeting Psychological Well-Being for Motor Neuron Disease Carers: A Systematic Review. Palliat. Support. Care 2022, 21, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; An, J.; Park, K.; Park, Y. Psychosocial Interventions for People with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Motor Neuron Disease and Their Caregivers: A Scoping Review. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelman, M.S. Psychosocial Intervention Research: Challenges, Strategies and Measurement Issues. Aging Ment. Health 2008, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritschler, T.; Langlois, N.; Hutton, B.; Shea, B.J.; Shorr, R.; Ng, S.; Dubois, S.; West, C.; Iorio, A.; Tugwell, P.; et al. Protocol for a Scoping Review of Outcomes in Clinical Studies of Interventions for Venous Thromboembolism in Adults. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e040122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, V.; Moodie, M.; Sultana, M.; Hunter, K.E.; Byrne, R.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Seidler, A.L.; Golley, R.; Taylor, R.W.; Hesketh, K.D.; et al. A Scoping Review of Outcomes Commonly Reported in Obesity Prevention Interventions Aiming to Improve Obesity-Related Health Behaviors in Children to Age 5 Years. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 Version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2020; pp. 406–451. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, M.T.; Rajić, A.; Greig, J.D.; Sargeant, J.M.; Papadopoulos, A.; Mcewen, S.A. A Scoping Review of Scoping Reviews: Advancing the Approach and Enhancing the Consistency. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.M. Behavioral Health Interventions: What Works and Why? In Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life; National Research Council (US) Panel on Race, Ethnicity, and Health in Later Life, Ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 643–676. [Google Scholar]

- Zarotti, N.; Deane, K.H.O.; Ford, C.E.L.; Simpson, J. Psychosocial Interventions Affecting Global Perceptions of Control in People with Parkinson’s Disease: A Scoping Review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 46, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, B.; O’connor, M.; Breen, L.J.; Kane, R. Feasibility, Acceptability and Potential Effectiveness of Dignity Therapy for Family Carers of People with Motor Neurone Disease. BMC Palliat. Care 2014, 13, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, M.S.; Cho, Y.; Fee, D.; Barkhaus, P.E. Skill, Confidence and Support: Conceptual Elements of a Child/Youth Caregiver Training Program in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis—The YCare Protocol. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2020, 10, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnini, F.; Phillips, D.; Haulman, A.; Bankert, M.; Simmons, Z.; Langer, E. An Online Non-Meditative Mindfulness Intervention for People with ALS and Their Caregivers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2022, 23, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharbafshaaer, M.; Buonanno, D.; Passaniti, C.; De Stefano, M.; Esposito, S.; Canale, F.; D’Alvano, G.; Silvestro, M.; Russo, A.; Tedeschi, G.; et al. Psychological Support for Family Caregivers of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis at the Time of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic: A Pilot Study Using a Telemedicine Approach. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 904841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhauser, K.E.; Olsen, A.; Johnson, K.S.; Sanders, L.L.; Olsen, M.; Ammarell, N.; Grossoehme, D. The Feasibility and Acceptability of a Chaplain-Led Intervention for Caregivers of Seriously Ill Patients: A Caregiver Outlook Pilot Study. Palliat. Support. Care 2016, 14, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugalde, A.; Mathers, S.; Hennessy Anderson, N.; Hudson, P.; Orellana, L.; Gluyas, C. A Self-Care, Problem-Solving and Mindfulness Intervention for Informal Caregivers of People with Motor Neurone Disease: A Pilot Study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoun, S.M.; Chochinov, H.M.; Kristjanson, L.J. Dignity Therapy for People with Motor Neuron Disease and Their Family Caregivers: A Feasibility Study. J. Palliat. Med. 2015, 18, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creemers, H.; Veldink, J.H.; Grupstra, H.; Nollet, F.; Beelen, A.; van den Berg, L.H. Cluster RCT of Case Management on Patients’ Quality of Life and Caregiver Strain in ALS. Neurology 2014, 82, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Wit, J.; Beelen, A.; Drossaert, C.H.C.; Kolijn, R.; Van Den Berg, L.H.; SchrÖder, C.D.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A. Blended Psychosocial Support for Partners of Patients with ALS and PMA: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2020, 21, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Groenestijn, A.C.; Schröder, C.D.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; Reenen, E.T.K.; van Veldink, J.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Quality of Life in Psychologically Distressed Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Their Caregivers: Results of a Prematurely Stopped Randomized Controlled Trial. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2015, 16, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNair, D.M.; Lorr, M.; Droppleman, L.F. Manual for the Profile of Mood States; Educational and Industrial Testing Services: San Diego, CA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondo, M.; Sechi, C.; Cabras, C. Psychometric Evaluation of Three Versions of the Italian Perceived Stress Scale. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1884–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabora, J.; Brintzenhofeszoc, K.; Jacobsen, P.; Curbow, B.; Piantadosi, S.; Hooker, C.; Owens, A.; Derogatis, L. A New Psychosocial Screening Instrument for Use with Cancer Patients. Psychosomatics 2001, 42, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herth, K. Abbreviated Instrument to Measure Hope: Development and Psychometric Evaluation. J. Adv. Nurs. 1992, 17, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Vanderwerker, L.C.; Maciejewski, P.K. A Case for Inclusion of Prolonged Grief Disorder in DSM-V. In Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice: Advances in Theory and Intervention; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 165–186. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Heffernan, C.; Tan, J. Caregiver Burden: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2020, 7, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarit, S.H.; Reever, K.E.; Bach-Peterson, J. Relatives of the Impaired Elderly: Correlates of Feelings of Burden. Gerontologist 1980, 20, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Given, C.W.; Given, B.; Stommel, M.; Collins, C.; King, S.; Franklin, S. The Caregiver Reaction Assessment (CRA) for Caregivers to Persons with Chronic Physical and Mental Impairments. Res. Nurs. Health 1992, 15, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.C. Validation of a Caregiver Strain Index. J. Gerontol. 1983, 38, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, M.; Guest, C. Application of a Multidimensional Caregiver Burden Inventory. Gerontologist 1989, 29, 798–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archbold, P.G.; Stewart, B.J.; Greenlick, M.R.; Harvath, T. Mutuality and Preparedness as Predictors of Caregiver Role Strain. Res. Nurs. Health 1990, 13, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heppner, P.P.; Petersen, C.H. The Development and Implications of a Personal Problem-Solving Inventory. J. Couns. Psychol. 1982, 29, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, C.; Hobart, J.; Chandola, T.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Peto, V.; Swash, M. Use of the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Tests of Data Quality, Score Reliability, Response Rate and Scaling Assumptions. J. Neurol. 2002, 249, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.R.; Hassan, S.A.; Lapointe, B.J.; Mount, B.M. Quality of Life in HIV Disease as Measured by the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire. AIDS 1996, 10, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinhauser, K.E.; Clipp, E.C.; Bosworth, H.B.; McNeilly, M.; Christakis, N.A.; Voils, C.I.; Tulsky, J.A. Measuring Quality of Life at the End of Life: Validation of the QUAL-E. Palliat. Support. Care 2004, 2, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterman, A.H.; Fitchett, G.; Brady, M.J.; Hernandez, L.; Cella, D. Measuring Spiritual Well-Being in People with Cancer: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.; Feuille, M.; Burdzy, D. The Brief RCOPE: Current Psychometric Status of a Short Measure of Religious Coping. Religions 2011, 2, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, G.; Hayes, A.; Kumar, S.; Greeson, J.; Laurenceau, J.P. Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation: The Development and Initial Validation of the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale-Revised (CAMS-R). J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2007, 29, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Xie, Q.; Huang, L.; Liu, L.; Armstrong, E.; Zhen, M.; Ni, J.; Shi, J.; Tian, J.; Cheng, W. Assessment of the Psychological Burden Among Family Caregivers of People Living with Alzheimer’s Disease Using the Zarit Burden Interview. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 82, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.T.; Kwok, T.; Lam, L.C.W. Dimensionality of Burden in Alzheimer Caregivers: Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Correlates of the Zarit Burden Interview. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2014, 26, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatter, S.; McDonald, K.R.; Stanmore, E.; Clare, L.; Leroi, I. Multidimensional Care Burden in Parkinson-Related Dementia. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2018, 31, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagell, P.; Alvariza, A.; Westergren, A.; Årestedt, K. Assessment of Burden Among Family Caregivers of People with Parkinson’s Disease Using the Zarit Burden Interview. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2017, 53, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssov, K.; Audureau, E.; Vandendriessche, H.; Morgado, G.; Layese, R.; Goizet, C.; Verny, C.; Bourhis, M.L.; Bachoud-Lévi, A.C. The Burden of Huntington’s Disease: A Prospective Longitudinal Study of Patient/Caregiver Pairs. Park. Relat. Disord. 2022, 103, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Shin, C.; Hwang, Y.S.; Oh, E.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.S.; Chung, S.J.; Sung, Y.H.; Yoon, W.T.; Cho, J.W.; et al. Caregiver Burden of Patients with Huntington’s Disease in South Korea. J. Mov. Disord. 2024, 17, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Kim, J.A. Factor Analysis of the Zarit Burden Interview in Family Caregivers of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2018, 19, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabkin, J.G.; Albert, S.M.; Rowland, L.P.; Mitsumoto, H. How Common Is Depression among ALS Caregivers? A Longitudinal Study. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2009, 10, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagnini, F.; Rossi, G.; Lunetta, C.; Banfi, P.; Castelnuovo, G.; Corbo, M.; Molinari, E. Burden, Depression, and Anxiety in Caregivers of People with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Psychol. Health Med. 2010, 15, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qutub, K.; Lacomis, D.; Albert, S.M.; Feingold, E. Life Factors Affecting Depression and Burden in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Caregivers. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2014, 15, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, A.C.; Gonçalves, E. Are Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Caregivers at Higher Risk for Health Problems? Acta Med. Port. 2016, 29, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- de Wit, J.; Beelen, A.; van den Heerik, M.S.; van den Berg, L.H.; Visser-Meily, J.M.A.; Schröder, C.D. Psychological Distress in Partners of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Progressive Muscular Atrophy: What’s the Role of Care Demands and Perceived Control? Psychol. Health Med. 2020, 25, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadi, A.M.; Galvin, M.; Heverin, M.; Hardiman, O.; Mooney, C. Prediction of Caregiver Quality of Life in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Using Explainable Machine Learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.; Teixeira, M.I.; Magalhães, B. The Role of Spirituality in People with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Their Caregivers: Scoping Review. Palliat. Support. Care 2023, 21, 914–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Tsukasaki, K.; Kyota, K. Relationship Between Resilience Factors and Caregiving Status of Families of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) in Japan. J. Community Health Nurs. 2024, 41, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galin, S.; Heruti, I.; Barak, N.; Gotkine, M. Hope and Self-Efficacy Are Associated with Better Satisfaction with Life in People with ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2018, 19, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, M.T.; Kub, J.; Hughes, M.T.; Terry, R.P.; Astrow, A.B.; Carbo, C.A.; Thompson, R.E.; Clawson, L.; Texeira, K.; Sulmasy, D.P. Family Health Care Decision Making and Self-Efficacy with Patients with ALS at the End of Life. Palliat. Support. Care 2008, 6, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnini, F.; Phillips, D.; Bosma, C.M.; Reece, A.; Langer, E. Mindfulness as a Protective Factor for the Burden of Caregivers of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 72, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipek, L.; Güneş Gencer, G.Y. Is Caregiver Burden of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Related to Caregivers’ Mindfulness, Quality of Life, and Patients’ Functional Level. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 126, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, V.; Felgoise, S.H.; Walsh, S.M.; Simmons, Z. Problem Solving Skills Predict Quality of Life and Psychological Morbidity in ALS Caregivers. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2009, 10, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consonni, M.; Telesca, A.; Dalla Bella, E.; Bersano, E.; Lauria, G. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients’ and Caregivers’ Distress and Loneliness during COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Palazzo, L.; Pompele, S.; de Vincenzo, C.; Perardi, M.; Ronconi, L. Coping and Managing ALS Disease in the Family during COVID-19: Caregivers’ Perspective. OBM Neurobiol. 2023, 7, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, M.; Santangelo, G.; Trojsi, F.; Di Somma, C.; Patrone, M.; Femiano, C.; Monsurrò, M.R.; Trojano, L.; Tedeschi, G. Coping Strategies and Psychological Distress in Caregivers of Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2017, 18, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).