Noninvasive Seizure Onset Zone Localization Using Janashia–Lagvilava Algorithm-Based Spectral Factorization in Granger Causality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Seizure Semiology

2.2. MRI

2.3. Neuropsychological Assessment

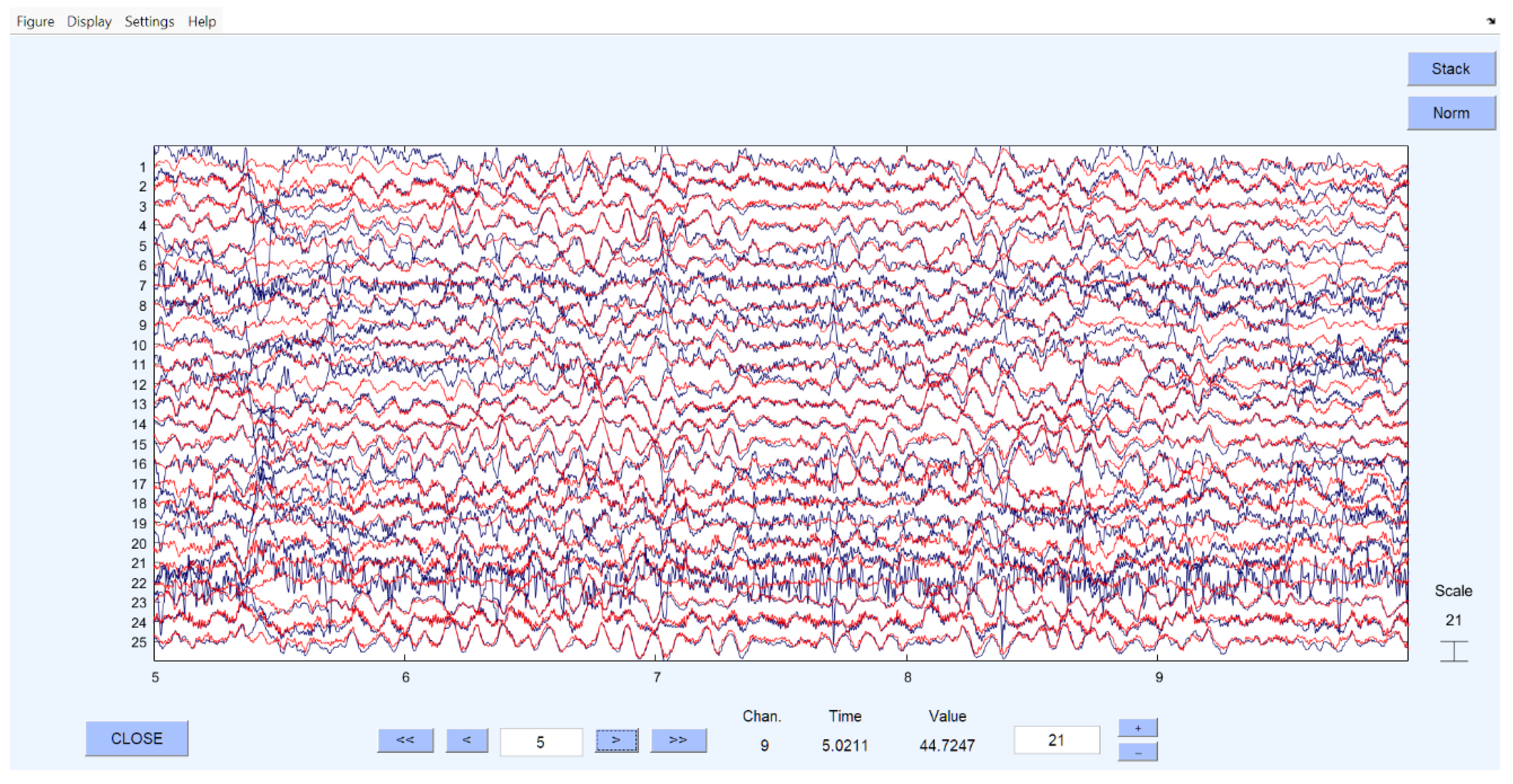

2.4. Video-EEG Monitoring

2.5. Preprocessing of EEG Recordings

- (A)

- EEG recordings were preprocessed using MATLAB (MATLAB and Statistics Toolbox Release 2010b, Update 4, Version 24.1, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The EEGLAB toolbox was used to remove evident artifacts and corrupted segments, as well as to attenuate line noise originating from electrical devices [25].

- (B)

- The preprocessed EEG data were further analyzed in EEGLAB using Independent Component Analysis (ICA). This procedure decomposed the signals into independent frequency components, allowing for the separation of neural oscillations from non-neural sources (e.g., muscular activity, line noise, ocular and cardiac artifacts). Non-brain components were removed, after which the EEG data were reconstructed.

- (C)

- In the final step, EEG channels identified as probable seizure onset zones (SOZs) were digitized and prepared for subsequent mathematical processing.

2.6. Mathematical Justification (Data Analyses Using GC and JLA)

2.7. Ethical Issue

3. Results

Demographics

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, R.S.; Cross, J.H.; French, J.A.; Higurashi, N.; Hirsch, E.; Jansen, F.E.; Lagae, L.; Moshé, S.L.; Peltola, J.; Roulet Perez, E.; et al. Operational Classification of Seizure Types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epilepsy. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Kwan, P.; Arzimanoglou, A.; Berg, A.T.; Brodie, M.J.; Allen Hauser, W.; Mathern, G.; Moshé, S.L.; Perucca, E.; Wiebe, S.; French, J. Definition of Drug Resistant Epilepsy: Consensus Proposal by the Ad Hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies: Definition of Drug Resistant Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2009, 51, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J. The Current Place of Epilepsy Surgery. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2018, 31, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinka, E.; Koepp, M.; Kalss, G.; Kobulashvili, T. Evidence Based Non-invasive Presurgical Evaluation for Patients with Drug Resistant Epilepsies. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2024, 37, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, B.M.; Epstein, C.M.; Dhamala, M. Localizing Epileptic Seizure Onsets with Granger Causality. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 88, 030701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragin, A.; Engel, J.; Wilson, C.L.; Fried, I.; Buzsáki, G. High-Frequency Oscillations in Human Brain. Hippocampus 1999, 9, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuello-Oderiz, C.; von Ellenrieder, N.; Dubeau, F.; Gotman, J. Influence of the Location and Type of Epileptogenic Lesion on Scalp Interictal Epileptiform Discharges and High-Frequency Oscillations. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 2153–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauscher, B.; von Ellenrieder, N.; Zelmann, R.; Rogers, C.; Nguyen, D.K.; Kahane, P.; Dubeau, F.; Gotman, J. High-Frequency Oscillations in the Normal Human Brain. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 84, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonen, O.M. High-Frequency Oscillations and Their Importance in Epilepsy. J. Neurol. Disord. 2014, 2, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlmans, M.; Jiruska, P.; Zelmann, R.; Leijten, F.S.S.; Jefferys, J.G.R.; Gotman, J. High-Frequency Oscillations as a New Biomarker in Epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 71, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frauscher, B.; Bartolomei, F.; Kobayashi, K.; Cimbalnik, J.; van ‘t Klooster, M.A.; Rampp, S.; Otsubo, H.; Höller, Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Asano, E.; et al. High-Frequency Oscillations: The State of Clinical Research. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 1316–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-P.; Wang, Y.-P.; Wang, Z.-H.; Wu, F.-Y.; Tang, L.-O.; Zhang, S.-W.; Pei, H.-T.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Xue, Q.; et al. High-Frequency Oscillations and the Seizure Onset Zones in Neocortical Epilepsy. Chin. Med. J. 2015, 128, 1724–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.J. Investigating Causal Relations by Econometric Models and Cross-Spectral Methods. Econometrica 1969, 37, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, L.; Worrell, G.A.; He, B. Seizure Source Imaging by Means of FINE Spatio-Temporal Dipole Localization and Directed Transfer Function in Partial Epilepsy Patients. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2012, 123, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.T. The Factorization of Matricial Spectral Densities. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1972, 23, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamala, M.; Rangarajan, G.; Ding, M. Analyzing Information Flow in Brain Networks with Nonparametric Granger Causality. NeuroImage 2008, 41, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ephremidze, L.; Saied, F.; Spitkovsky, I.M. On the Algorithmization of Janashia-Lagvilava Matrix Spectral Factorization Method. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2018, 64, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ephremidze, L.; Gamkrelidze, A.; Spitkovsky, I. On the Spectral Factorization of Singular, Noisy, and Large Matrices by Janashia-Lagvilava Method. Trans. A. Razmadze Math. Inst. 2022, 176, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.A.; Dhamala, M.; Robinson, P.A. Brain Dynamics and Structure-Function Relationships via Spectral Factorization and the Transfer Function. Neuroimage 2021, 235, 117989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Muzio, B.; Al Kabbani, A.; McArdle, D. Epilepsy Protocol (MRI); Radiopaedia.org: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV); Pearson: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Memory Scale–Fourth Edition (WMS-IV) [Test Kit]; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, N.; Acharya, J.; Benickzy, S.; Caboclo, L.; Finnigan, S.; Kaplan, P.W.; Shibasaki, H.; Pressler, R.; van Putten, M.J.A.M. A Revised Glossary of Terms Most Commonly Used by Clinical Electroencephalographers and Updated Proposal for the Report Format of the EEG Findings. Revision 2017. Clin. Neurophysiol. Pract. 2017, 2, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.; Seth, A.K. The MVGC Multivariate Granger Causality Toolbox: A New Approach to Granger-Causal Inference. J. Neurosci. Methods 2014, 223, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ephremidze, L.; Vatsadze, S. Stationary Processes, Wiener-Granger Causality, and Matrix Spectral Factorization. In Statistics of Random Processes and Optimal Control; Springer Nature volume dedicated to Albert Shiryaev; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J. Early Surgical Therapy for Drug-Resistant Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: A Randomized Trial. JAMA 2012, 307, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryvlin, P.; Cross, J.H.; Rheims, S. Epilepsy Surgery in Children and Adults. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 1114–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guery, D.; Rheims, S. Clinical Management of Drug Resistant Epilepsy: A Review on Current Strategies. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021, 17, 2229–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovac, S.; Vakharia, V.N.; Scott, C.; Diehl, B. Invasive Epilepsy Surgery Evaluation. Seizure 2017, 44, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, R.; Mangano, F.T.; Horn, P.S.; Holland, K.D.; Rose, D.F.; Glauser, T.A. Adverse Events Related to Extraoperative Invasive EEG Monitoring with Subdural Grid Electrodes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Epilepsia 2013, 54, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppler, M.B.; Sayegh, A.S.; Maas, M.; Venkat, A.; Hemal, S.; Desai, M.M.; Hung, A.J.; Grantcharov, T.; Cacciamani, G.E.; Goldenberg, M.G. Automated Capture of Intraoperative Adverse Events Using Artificial Intelligence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Gurevich, S.; Teti, S.; Guerrera, M.F.; Zelleke, T.; Gaillard, W.D.; Oluigbo, C.O. Invasive Intracranial Electroencephalography Monitoring in the Child with a Bleeding Disorder: Challenges and Considerations. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2024, 60, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorlag, L.; Van Klink, N.E.C.; Kobayashi, K.; Gotman, J.; Braun, K.P.J.; Zijlmans, M. High-Frequency Oscillations in Scalp EEG: A Systematic Review of Methodological Choices and Clinical Findings. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 137, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelmann, R.; Lina, J.M.; Schulze-Bonhage, A.; Gotman, J.; Jacobs, J. Scalp EEG Is Not a Blur: It Can See High Frequency Oscillations Although Their Generators Are Small. Brain Topogr. 2014, 27, 683–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, A.M.; Schoffelen, J.-M. A Tutorial Review of Functional Connectivity Analysis Methods and Their Interpretational Pitfalls. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2016, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLaurin, J.N.; Robinson, P.A. Determination of Effective Brain Connectivity from Activity Correlations. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 99, 042404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

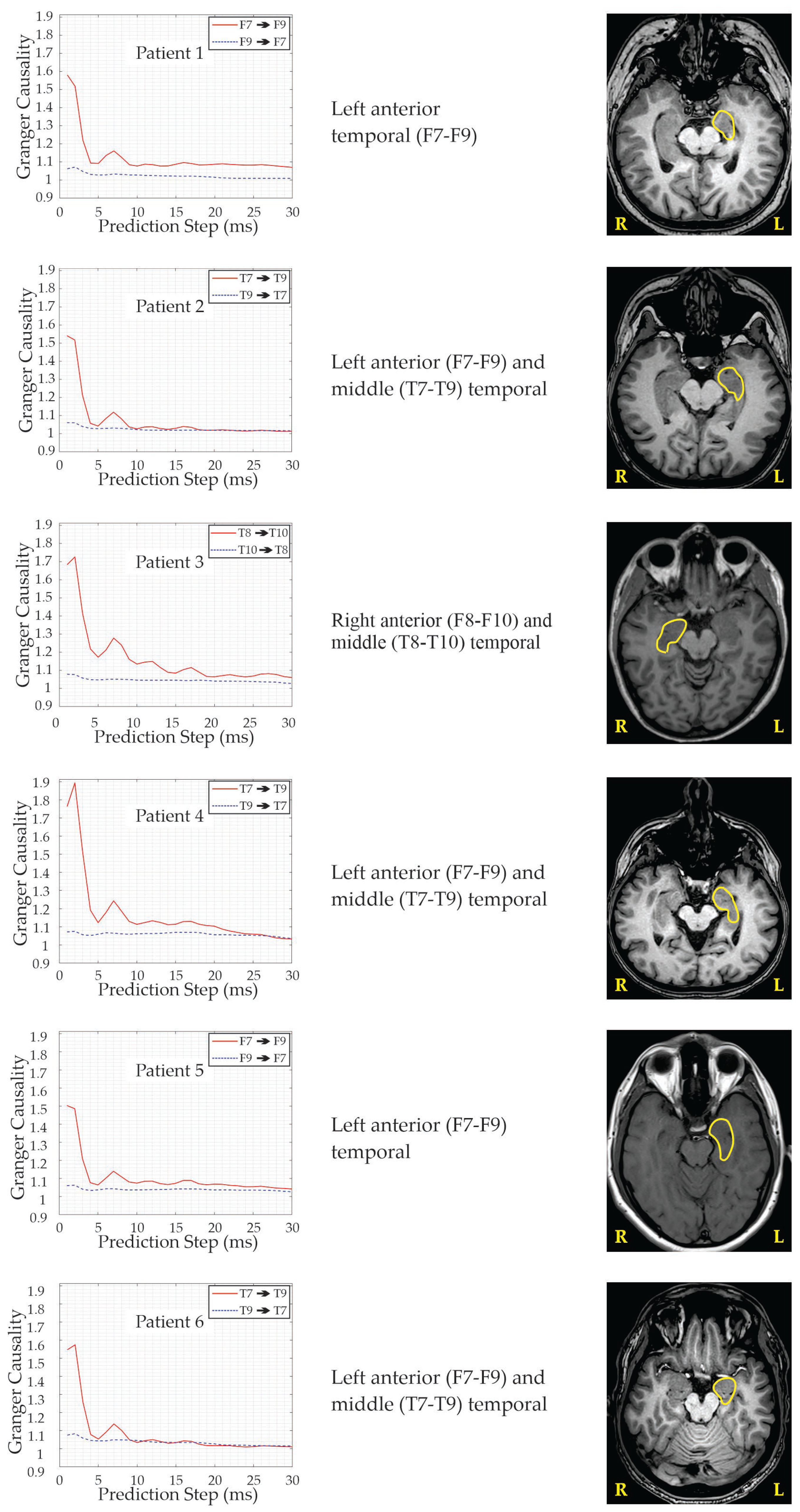

| Patient’s N/Age/Gender | Age at Seizure Onset | Seizure Semiology | EEG Interictal | EEG Ictal with Scalp Electrode Placement | MRI Eloquent Area/Side | Neuro-Psychology/Area/Side | Concordance of the Modalities | Side and Area of Performed Surgery | Early Post-Surgery Period | Outcome | Follow Up (Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/28/Male | 6 | Focal—with fear, impaired consciousness and oral automatisms | Bi-Temporal | L-anterior Temporal (F7–F9) | L-HS | L-Medial Temporal | +(−)+++ | L-Hippo-campectomy (AASJ15) | One FBTCS 3rd month after surgery | Engel 1a | 16 |

| 2/40/Female | 20 | Focal—preserved consciousness, with pressure in head and heating | L-Temporal | L-anterior (F7–F9) and middle (T7–T9) Temporal | L-HS | Bi-Frontal, R-Parietal | ++++(−) | L-Hippo-campectomy (AASJ15) | _ | Engel 1b | 5 |

| 3/42/Female | 9 | Focal—unpleasant sensation in the mesogastrium, with fear and impaired consciousness | Bi-Temporal | R-anterior (F8–F10) and middle (T8–T10) Temporal | R-HS | Bi-temporal | +(−)++(−) | R-Hippo-campectomy (AASJ15) | _ | Engel 1a | 9 |

| 4/43/Female | 27 | Focal—epigastric aura, tachycardia, impaired consciousness and oral automatisms | L-Temporal | L-anterior (F7–F9) and middle (T7–T9) Temporal | L-HS | Bi-Temporal | ++++(−) | L-Hippo-campectomy (AASJ15) | One FBTCS within 24 h of surgery | Engel 1a | 9 |

| 5/43/Male | 14 | Focal—with unpleasant taste, “uncooked beans”, tachycardia, inadequate speech; Impairment of consciousness, oral and manual automatisms, more prominent in the left hand. | L-Temporal | L-anterior Temporal (F7–F9) | L-VS | R-Temporal and Frontal | ++++(−) | L-Hippo-campectomy (AASJ15) | One FBTCS within 24 h of surgery | Engel 1a | 5 |

| 6/30/Male | 8 | Feeling of ringing in the ears, unexplained fear, impaired consciousness, deviation of the head and eyes to the left, oral and left manual automatisms, dystonia in the right hand, up to 1 min | L-Temporal | L-anterior (F7–F9) and middle (T7–T9) Temporal | L-HS L-Peri-ventricular Heterotopia | L-Temporal | +++++ | L-Hippo-campectomy (AASJ15) | _ | Engel 1a | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kasradze, S.; Lomidze, G.; Ephremidze, L.; Gagoshidze, T.; Japaridze, G.; Alkhidze, M.; Jishkariani, T.; Dhamala, M. Noninvasive Seizure Onset Zone Localization Using Janashia–Lagvilava Algorithm-Based Spectral Factorization in Granger Causality. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121334

Kasradze S, Lomidze G, Ephremidze L, Gagoshidze T, Japaridze G, Alkhidze M, Jishkariani T, Dhamala M. Noninvasive Seizure Onset Zone Localization Using Janashia–Lagvilava Algorithm-Based Spectral Factorization in Granger Causality. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121334

Chicago/Turabian StyleKasradze, Sofia, Giorgi Lomidze, Lasha Ephremidze, Tamar Gagoshidze, Giorgi Japaridze, Maia Alkhidze, Tamar Jishkariani, and Mukesh Dhamala. 2025. "Noninvasive Seizure Onset Zone Localization Using Janashia–Lagvilava Algorithm-Based Spectral Factorization in Granger Causality" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121334

APA StyleKasradze, S., Lomidze, G., Ephremidze, L., Gagoshidze, T., Japaridze, G., Alkhidze, M., Jishkariani, T., & Dhamala, M. (2025). Noninvasive Seizure Onset Zone Localization Using Janashia–Lagvilava Algorithm-Based Spectral Factorization in Granger Causality. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1334. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121334