Post-Varicella Arteriopathy as a Cause of Pediatric Arterial Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Case Report

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Pediatric patients (aged 0–18 years);

- Condition: Cerebral arteriopathy, vasculopathy, or arterial ischemic stroke occurring after varicella infection;

- Study types: Case reports, case series, and retrospective or prospective observational studies;

- Outcomes of interest: Clinical presentation, imaging findings, diagnostic approaches, treatments, and outcomes;

- Language: Articles published in English or with an English abstract available.

3.3. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies involving adults;

- Studies not clearly associating varicella infection with arteriopathy or stroke;

- Review articles, editorials, and conference abstracts (however, their references were screened for eligible primary studies);

- Non-English publications.

3.4. Search Strategy

3.5. Study Selection

3.6. Data Extraction

- Study characteristics: Authors, year, country, study type;

- Patient demographics: Number of patients, age;

- Clinical data: Symptoms, timing of stroke after varicella;

- Imaging findings: MRI/MRA results;

- Diagnosis of PVA;

- Treatment modalities: Antiviral therapy, corticosteroids, antiplatelets/anticoagulants;

- Clinical outcomes.

3.7. Data Synthesis

3.8. Quality Appraisal

4. Results

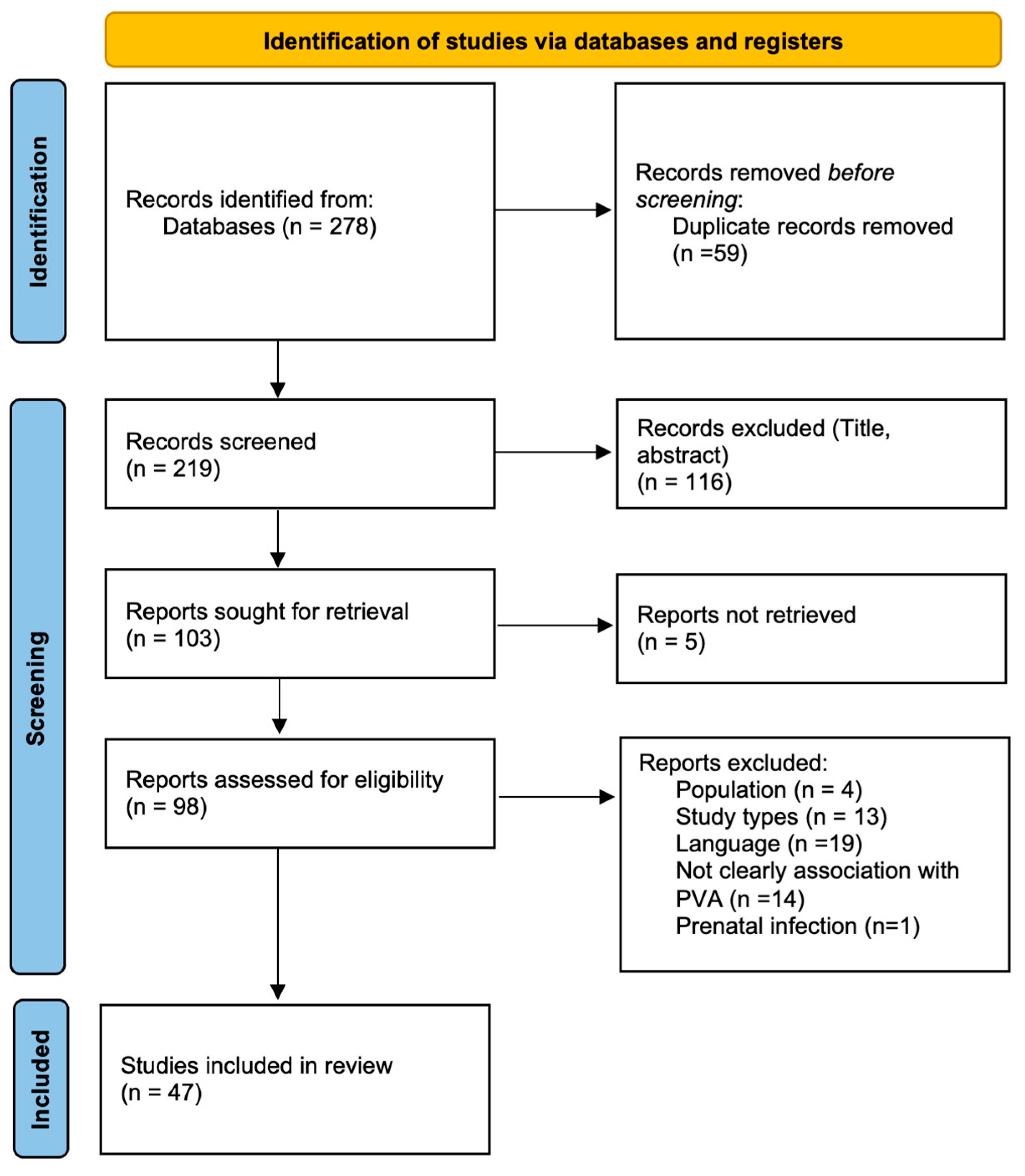

4.1. Study Selection

4.2. Study Characteristics

4.3. Patient Demographics and Clinical Presentation

- Hemiparesis or hemiplegia (~79%);

- Language impairment (~34%);

- Seizures (~19%);

- Facial asymmetry or cranial nerves involvement (~17%);

- Choreiform movements (~17%);

- Altered consciousness (~8%).

4.4. Imaging and Diagnosis

- Unilateral and focal involvement of anterior circulation arteries, especially of MCA, followed by ACA and supraclinoid ICA;

- Ischemic infarcts in the basal ganglia and internal capsule regions in most patients;

- Posterior circulation involvement and multifocal lesions.

- Positive VZV-DNA by PCR in 39% of tested patients;

- Positive anti-VZV IgG in 48% of tested patients.

4.5. Treatment Modalities

- Antiviral therapy (IV acyclovir) in 34% of cases, for a duration of 14–21 days;

- Corticosteroids (prednisone or methylprednisolone) in 20% of cases;

- Antiplatelet therapy (ASA) in 77% of cases, often continued long-term.

- Anticoagulants such as low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), warfarin, or dipyridamole or a combination therapy with antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents in selected cases;

- One case involved intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA);

- Another patient underwent a combined mechanical thrombectomy technique.

4.6. Outcomes

- Complete recovery in 43% of children;

- Residual neurological deficits (e.g., mild motor deficits, seizures) in 45%;

- Recurrence of stroke was rare (reported in ~11% of cases);

- Mortality was reported in only 2 patients.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VZV | Varicella-Zoster Virus |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| AIS | Arterial Ischemic Stroke |

| TIA | Transient Ischemic Attack |

| PVA | Post Varicella Arteriopathy |

| MCA | Middle Cerebral Artery |

| ACA | Anterior Cerebral Artery |

| ICA | Internal Carotid Artery |

| TCA | Transient Cerebral Arteriopathy |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| v-EEG | Video-Electroencephalography |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRA | Magnetic Resonance Angiography |

| PVCA | Post Varicella Cerebral Arteriopathy |

| MTHFR | Methylenetetrahydrofolate Reductase |

| IV | Intravenous |

| IM | Intramuscular |

| ASA | Acetylsalicylic Acid |

| LMWH | Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin |

| Rt-PA | Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator |

References

- World Health Organization. Varicella and herpes zoster vaccines: WHO position paper, June 2014. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 2014, 89, 265–287. [Google Scholar]

- Freer, G.; Pistello, M. Varicella-zoster virus infection: Natural history, clinical manifestations, immunity and current and future vaccination strategies. New Microbiol. 2018, 41, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gershon, A.A.; Breuer, J.; Cohen, J.I.; Cohrs, R.J.; Gershon, M.D.; Gilden, D.; Grose, C.; Hambleton, S.; Kennedy, P.G.E.; Oxman, M.N.; et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015, 1, 15016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertamino, M.; Signa, S.; Vagelli, G.; Caorsi, R.; Zanetti, A.; Volpi, S.; Losurdo, G.; Amico, G.; Dodi, I.; Prato, G.; et al. An atypical case of post-varicella stroke in a child presenting with hemichorea followed by late-onset inflammatory focal cerebral arteriopathy. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2021, 11, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleza, P.; Fernandes, J.; Afonso, A.; Silva, H.; Jordão, M.J. Transient ischemic attacks in a child with post-varicella arteriopathy and MTHFR homozigotic mutation C677T. Arq. De Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2008, 66, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmuth, I.G.; Mølbak, K.; Uldall, P.V.; Poulsen, A. Post-varicella Arterial Ischemic Stroke in Denmark 2010 to 2016. Pediatr. Neurol. 2018, 80, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häusler, M.G.; Ramaekers, V.T.; Reul, J.; Meilicke, R.; Heimann, G. Early and late onset manifestations of cerebral vasculitis related to varicella zoster. Neuropediatrics 1998, 29, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanthier, S.; Armstrong, D.; Domi, T.; Deveber, G. Post-varicella arteriopathy of childhood: Natural history of vascular stenosis. Neurology 2005, 64, 660–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askalan, R.; Laughlin, S.; Mayank, S.; Chan, A.; MacGregor, D.; Andrew, M.; Curtis, R.; Meaney, B.; Deveber, G. Chickenpox and stroke in childhood: A study of frequency and causation. Stroke 2001, 32, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabrier, S.; Sébire, G.; Fluss, J. Transient Cerebral Arteriopathy, Postvaricella Arteriopathy, and Focal Cerebral Arteriopathy or the Unique Susceptibility of the M1 Segment in Children With Stroke. Stroke 2016, 47, 2439–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okanishi, T.; Kondo, A.; Inoue, T.; Maegaki, Y.; Ohno, K.; Togari, H. Bilateral middle cerebral artery infarctions following mild varicella infection: A case report. Brain Dev. 2009, 31, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, M.A.; Cohrs, R.J.; Mahalingam, R.; Wellish, M.C.; Forghani, B.; Schiller, A.; Safdieh, J.E.; Kamenkovich, E.; Ostrow, L.W.; Levy, M.; et al. The varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: Clinical, CSF, imaging, and virologic features. Neurology 2008, 70, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miravet, E.; Danchaivijitr, N.; Basu, H.; Saunders, D.E.; Ganesan, V. Clinical and radiological features of childhood cerebral infarction following varicella zoster virus infection. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Pereira, C.; Silva, F.; Garcia, T.; Ribeiro, J.A. Ischemic Cerebellar Stroke in a 4-Year-Old Boy After Chickenpox: An Atypical Vascular Involvement. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 30, 105719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiber, H.; Lange, P. Quantification of virus-specific antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid and serum: Sensitive and specific detection of antibody synthesis in brain. Clin. Chem. 1991, 37, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, M.A.; Forghani, B.; Mahalingam, R.; Wellish, M.C.; Cohrs, R.J.; Russman, A.N.; Katzan, I.; Lin, R.; Gardner, C.J.; Gilden, D.H. The value of detecting anti-VZV IgG antibody in CSF to diagnose VZV vasculopathy. Neurology 2007, 68, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amlie-Lefond, C.; Gilden, D. Varicella Zoster Virus: A Common Cause of Stroke in Children and Adults. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2016, 25, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilden, D.; Cohrs, R.J.; Mahalingam, R.; Nagel, M.A. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: Diverse clinical manifestations, laboratory features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009, 8, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteventi, O.; Chabrier, S.; Fluss, J. Current management of post-varicella stroke in children: A literature review. Arch. De Pediatr. 2013, 20, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magagnini, M.C.; Spina, L.L.; Gioé, D.; Campo, G.D.; Belfiore, G.; Smilari, P.; Greco, F. A case of postvaricella cerebral angiopathy with a good outcome in a child. J. Pediatr. Neurosci. 2015, 10, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, S.B.; Amlie-Lefond, C.; Perez, F.A.; Melvin, A.J. Varicella-Associated Stroke. J. Pediatr. 2018, 199, 281–281.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.M.; Farhat, S.C.L.; Lucato, L.T.; Sakano, T.M.S.; Plaggert, P.S.G.; Casella, E.B.; da Paz, J.A.; Schvartsman, C. Post-varicella arterial ischemic stroke in children and neurocognitive performance: A 4-year follow-up study. Einstein 2022, 20, eAO6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.F.; Pais, P.; Monteiro, J.P. Chickenpox and stroke in children: Case studies and literature review. Acta Paediatr. 2014, 103, e176–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertamino, M.; Signa, S.; Veneruso, M.; Prato, G.; Caorsi, R.; Losurdo, G.; Teutonico, F.; Esposito, S.; Formica, F.; Tovaglieri, N.; et al. Expanding the clinical and neuroimaging features of post-varicella arteriopathy of childhood. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 4846–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Science, M.; Macgregor, D.; Richardson, S.E.; Mahant, S.; Tran, D.; Bitnun, A. Central nervous system complications of varicella-zoster virus. J. Pediatr. 2014, 165, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.L.; Minassian, C.; Ganesan, V.; Langan, S.M.; Smeeth, L. Chickenpox and risk of stroke: A self-controlled case series analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darteyre, S.; Hubert, A.; Chabrier, S.; Bessaguet, S.; Morel, M.N. In vivo evidence of arterial wall inflammation in childhood varicella-zoster virus cerebral vasculopathy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 56, 1219–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, F.; Panyaping, T.; Tedesqui, G.; Sossa, D.; Leite, C.C.; Castillo, M. Varicella zoster CNS vascular complications: A report of four cases and literature review. Neuroradiol. J. 2014, 27, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, K.P.J.; Bulder, M.M.M.; Chabrier, S.; Kirkham, F.J.; Uiterwaal, C.S.P.; Tardieu, M.; Sebire, G. The course and outcome of unilateral intracranial arteriopathy in 79 children with ischaemic stroke. Brain 2009, 132, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccone, S.; Faggioli, R.; Calzolari, F.; Sartori, S.; Calderone, M.; Borgna-Pignatti, C. Stroke after varicella-zoster infection: Report of a case and review of the literature. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2010, 29, 864–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunkhase-Heinl, U.; Stausbøl-Grøn, B.; Christensen, J.; Ostergaard, J.R. Post-varicella angiopathy: A series of 4 patients with focus on virologic and neuroimaging findings. Pediatr. Neurol. 2014, 50, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buompadre, C.M.; Arroyo, H.A. Basal ganglia and internal capsule stroke in childhood-Risk factors, neuroimaging, and outcome in a series of 28 patients: A tertiary hospital experience. J. Child Neurol. 2009, 24, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragata, I.; Morais, T.; Silva, R.; Nunes, A.P.; Loureiro, P.; Martins, J.D.; Pamplona, J.; Carvalho, R.; Baptista, M.; Reis, J. Endovascular treatment of pediatric ischemic stroke: A single center experience and review of the literature. Interv. Neuroradiol. 2021, 27, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davico, C.; Canavese, C.; Tocchet, A.; Brusa, C.; Vitiello, B. Acute hemichorea can be the only clinical manifestation of post-varicella vasculopathy: Two pediatric clinical cases. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriuchi, H.; Rodriguez, W. Role of varicella-zoster virus in stroke syndromes. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2000, 19, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougeot, C.; Boissier, C.; Chabrier, S. Post-varicella arteriopathy: Benefits of using serial transcranial Doppler examinations. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2006, 10, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawatani, M.; Nakai, A.; Okuno, T.; Tsukahara, H.; Ohshima, Y.; Mayumi, M. A case of intracranial saccular aneurysm after primary varicella zoster virus infection. Brain Dev. 2012, 34, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyên, P.; Munzer, M.; Reynaud, J.; Richard, O.; Pouzol, P.; François, P. Varicella and thrombotic complications associated with transient protein C and protein S deficiencies in children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 1994, 153, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driesen, Y.; Verweij, M.; De Maeseneer, M.; De Dooy, J.; Wojciechowski, M.; Akker, M.V.D. Vascular complications of varicella description of 4 cases and a review of literature. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2015, 34, 1256–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. Ischaemic stroke in children secondary to post varicella angiopathy. Item Type Article Ischaemic Stroke In Children Secondary to Post Varicella Angiopathy. Ir. Med. J. 2007, 100, 332–333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sabry, A.; Hauk, P.J.; Jing, H.; Su, H.C.; Stence, N.V.; Mirsky, D.M.; Nagel, M.A.; Abbott, J.K.; Dragone, L.L.; Armstrong-Wells, J.; et al. Vaccine strain varicella-zoster virus–induced central nervous system vasculopathy as the presenting feature of DOCK8 deficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1225–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodensteiner, J.B.; Hille, M.R.; Riggs, J.E. Clinical Features of Vascular Thrombosis Following Varicella. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1992, 146, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, K.; Çalişkan, M.; Akdeniz, C.; Aydinli, N.; Karaböcüoğlu, M.; Uzel, N. Acute childhood hemiplegia associated with chickenpox. Pediatr. Neurol. 1998, 18, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morino, M.; Yamano, H.; Sasaki, N. Role of varicella virus and anticardiolipin antibodies in the development of stroke in a patient with Down syndrome associated with Moyamoya syndrome. Pediatr. Int. 2009, 51, 300–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, A.B.; Singhal, B.S.; Ursekar, M.A.; Koroshetz, W.J. Serial MR angiography and contrast-enhanced MRI in chickenpox-associated stroke. Neurology 2001, 56, 815–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danchaivijitr, N.; Miravet, E.; Saunders, D.E.; Cox, T.; Ganesan, V. Post-varicella intracranial haemorrhage in a child. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, L.; Rich, P.M. Can mild head injury cause ischaemic stroke? Arch. Dis. Child. 2003, 88, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulder, M.M.M.; Houten, R.T.; Klijn, C.J.M.; Braun, K.P.J. Unilateral movement disorder as a presenting sign of paediatric post-varicella angiopathy. Case Rep. 2013, 2013, bcr2013009437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, V.; Kirkham, F.J. Mechanisms of ischaemic stroke after chickenpox. Arch. Dis. Child. 1997, 76, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.M.; Caduff, J.H.; Gebbers, J.O. Fatal varicella-zoster virus antigen-positive giant cell arteritis of the central nervous system. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2000, 19, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, H.; Higuchi, Y.; Tsuji, M. Recurrent strokes after varicella. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 47, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, K.; Sert, A.; Güze, E.A.; Kiresi, D.A. Acute childhood hemiplegia associated with chickenpox and elevated anticardiolipin antibody. J. Child Neurol. 2006, 21, 890–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darteyre, S.; Chabrier, S.; Presles, E.; Bonafé, A.; Roubertie, A.; Echenne, B.; Leboucq, N.; Rivier, F. Lack of progressive arteriopathy and stroke recurrence among children with cryptogenic stroke. Neurology 2012, 79, 2342–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, L.; Gentilomo, C.; Sartori, S.; Calderone, M.; Simioni, P.; Laverda, A.M. Varicella and stroke in children: Good outcome without steroids. Clin. Appl. Thromb. 2011, 17, E127–E130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, W.P.; Clarke, M.J.; Cloft, H.J.; Lanzino, G.L. Going viral: Fusiform vertebrobasilar and internal carotid aneurysms with varicella angiitis and common variable immunodeficiency. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2009, 4, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losurdo, G.; Giacchino, R.; Castagnola, E.; Gattorno, M.; Costabel, S.; Rossi, A.; Amato, S.; Di Pietro, P.; Molinari, A.C. Cerebrovascular disease and varicella in children. Brain Dev. 2006, 28, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sébire, G.; Meyer, L.; Chabrier, S. Varicella as a risk factor for cerebral infarction in childhood: A case-control study. Ann. Neurol. 1999, 45, 679–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fullerton, H.J.; Hills, N.K.; Wintermark, M.; Dlamini, N.; Amlie-Lefond, C.; Dowling, M.M.; Jordan, L.C.; Friedman, N.R.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Grose, C.; et al. Evidence of Varicella Zoster Virus Reactivation in Children With Arterial Ischemic Stroke: Results of the VIPS II Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e039184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devinsky, O.; Cho, E.-S.; Petito, C.K.; Price, R.W. Herpes zoster myelitis. Brain 1991, 114, 1181–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, S.E.; Dover, D.C.; Hill, M.D.; Kirton, A.; Simmonds, K.A.; Svenson, L.W. Is varicella vaccination associated with pediatric arterial ischemic stroke? A population-based cohort study. Vaccine 2018, 36, 2764–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grose, C. Stroke after varicella and zoster ophthalmicus: Another indication for treatment and immunization. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2010, 29, 868–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, V.; Prengler, M.; Wade, A.; Kirkham, F.J. Clinical and Radiological Recurrence After Childhood Arterial Ischemic Stroke. Circulation 2006, 114, 2170–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Author, Year) | Country | Study Type | N° of Patients | Age Range/Mean Age | Time from Varicella to Stroke | Clinical Presentation | Imaging Findings (MRI/MRA) | Diagnosis of PVA | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vora SB et al., 2018 [23] | USA | Case report | 1 | 11 mo | 2–3 mo | Hemiparesis | Left MCA stenosis, stroke | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV CSF VZV DNA/IgG + | Acyclovir | Weakness improved, progressive arteriopathy at imaging |

| Rodrigues RM et al., 2022 [24] | Brazil | Case series | 7 | 1.3–4 y/3.8 y | 3.8 mo | Hemiparesis, aphasia, hemi-facial paralysis, focal seizures, dysarthria | (4) unilateral stenosis MCA or/and ICA and ACA, (3) infarction | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV IgG + (3) | Acyclovir (2) Acyclovir + corticosteroids (1) ASA (7) | (3) no deficit, 2 mild hemiparesis, 1 epilepsy and hemiparesis No recurrence of AIS in 4 years |

| Helmuth IG et al., 2018 [6] | Denmark | Retrospective cohort | 15 | 1–6 y/4 y | 3 w–10 mo/4.6 mo (median) | Hemiparesis, facial nerve paresis, dysarthria, unilateral choreiform movements (1), seizures (2), headache or vomiting (8) | (12) unilateral stenosis of MCA or/and ICA, or/and ACA or basilar artery, (3) infarction BG | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV (12), CSF VZV DNA + (9) and IgG + (3) | Acyclovir (3), Acyclovir + corticosteroids (10) ASA (14) | (8) neurological sequelae No recurrence of AIS |

| Reis AF et al.,2013 [25] | Portugal | Case series and literature review | 4 | 10 mo–4.5 y/2.33 y | 1–10 mo/5.75 mo (median) | Hemiparesis, dysarthria | (3) right MCA stenosis, (1) stroke BG | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV or involvement of basal ganglia, CSF VZV DNA − | ASA, (1)LMWH + ASA | (3) residual dystonia, (1) hemiparesis. (2) complete resolution, (1) residual stenosis, (1) stable No recurrence of AIS |

| Bertamino M et al., 2021 [26] | Italy | Retrospective observational | 22 | 1.7–10 y/4 y | 2.8–8.6 mo/4.5 mo (median) 3 cases: 13–32.4 mo | Hemiparesis (73%), unilateral choreiform movements, language disorders, partial visual loss, strabismus and/or nystagmus, seizures, vomiting, altered state of consciousness | Focal stenosis of ICA, MCA, ACA; (7/22) only infarction of BG or brainstem Totally infarct of BG (18/22) | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA + (3/22) e IgG + (8/22) | Acyclovir (12/22) Acyclovir + corticosteroid (10/22) ASA (22/22) anticoagulant (11/22) | Motor deficits (12/22), cognitive impairment (8/22 Regression of stenosis (6/15), persistent narrowing (9/15) [4 improved, 3 stable, 2 worsened] (5) recurrent AIS |

| Lanthier et al., 2005 [8] | Canada | Retrospective cohort | 23 | 1–10.4 y/4,4 y | 4–47 w/17 w (median) | NR | Unilateral unifocal or multifocal stenosis MCA, ACA, ICA | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV | LMWH or/and ASA | Hemiparesis (13/23) hemidystonia (6/23) hemisensory deficit (3/23) speech problem (3/23), epilepsy (1/23) no deficit (9/23) AIS/TIA recurrence (8/23) |

| Science et al., 2014 [27] | Canada | Retrospective observational | 10 | 2–11.5 y/4.5 y (mean) | 2–26 w/4.25 w (median) | Hemiparesis, speech problem, facial weakness, blurred vision, hallucinations | Stenosis of MCA; infarct of BG | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA + (1/5) | Acyclovir (3) | hemiparesis (1/10), weakness of arm and short-term memory problems (1/10) increased tone of side (1/10), no deficit (7/10) |

| Thomas et al., 2013 [28] | UK | Case series | 60 | 3.9 y (mean) | 0–6 mo | NR | NR | VZV-associated AIS | NR | 4-times increased stroke risk in 6 months post-VZV |

| Miravet et al., 2007 [3] | UK | Case series | 24 | 2 m–6 y/2 y 9 m (mean) | 1 w–12 m/4 m (median) | Hemiparesis, chorea, facial weakness, dysarthria, ataxia, seizure, decreased vision | Stenosis of MCA (1 bilateral), ACA, ICA, terminal internal carotid artery (1 bilateral), infarction of BG and subcortical white matter or cortical tissue | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA + (1/8) IgG + (14/14) | ASA or/and anticoagulants | Hemiparesis (18/24) behavioral problems (7/24) TIA (6/24) imaging of disease improved (11/24) resolution (1/24) increased or stable (12/24) |

| Darteyre S et al., 2012 [29] | France | Retrospective cohort | 9 on 28 | 3.87 y (mean) | NR | NR | Unilateral and focal stenosis of MCA and terminal internal carotid artery 1 irregularity, 1 dissection | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV | ASA (1 no treatment) | no neurologic impairment (3/8), (2) cognitive impairment, (1) speech disorder, (5) motor impairment, (2) epilepsy No recurrence of AIS |

| Chiang et al., 2014 [30] | USA/Brazil | Case series | 2 on 4 | 11 mo–3 y/1.96 y (mean) | 15 d–1 y/0.52 y (median) | Hemiparesis, seizure | Posterior pontine subacute infarct, left BG infarct | Imaging post-VZV | Acyclovir | No follow-up |

| Askalan et al., 2001 [9] | Canada | Prospective cohort study | 22 | 6 mo–10 y/4 y | 1–11 mo/5.2 mo (median) | Hemiparesis, seizure | BG infarct, infarcts of anterior circulation, large vessel stenosis | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV or imaging of infarct post-VZV | LMWH (4/22) or/and coumadin (1/22) and/or ASA (13/22) | Neurological deficits mild (10), moderate (2), severe (3) no deficit (7) Recurrence AIS (10) with stenosis (9) |

| Braun K. P. J. et al., 2008 [31] | UK, France, Netherlands | Retrospective cohort study | 32 | 0.3–16.3 y/4.8 y (for the TCA group, which includes PVA) | Within 12 months prior to stroke | Hemiparesis (1) no data for other | Unilateral focal stenosis MCA, ACA, ICA and basal ganglia infarcts | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV | ASA (58/7) of TCA (2) Acyclovir and ASA (10) anticoagulant | Recurrent neurological symptoms (13/74 with TCA) No patients in the progressive arteriopathy group had VZV |

| Ciccone S. et al., 2010 [32] | Italy | Case report | 1 | 5 y | 3 months after VZV reactivation (primary infection at 1 year old) | episodes of weakness of the left arm, left lower leg, walking difficulties, and dysarthria | Unilateral focal stenosis MCA ischemic lesion of BG | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA + | Acyclovir + LMWH + ASA | 1 y later minimal reduction in motility of the left hand and in left leg coordination during sport activity, gliosis at RM |

| Dunkhase-Heinl et al., 2014 [33] | Denmark | Case Series | 4 | 13–22 mo/17 mo (mean) | 4 w–6 mo/3.4 mo (median) | Hemiparesis vomiting | Stenosis of MCA, ICA; infarct of BG | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA + (3/4) IgG + (2/4) | Acyclovir + corticosteroid (4/4), ASA (4/4) | Mild motor and cognitive deterioration (3) (3) normalization of stenosis, (1) residual stenosis, (1) stable |

| Bertamino M et al., 2021 [4] | Italy | Case report | 1 | 6 y | 7 mo | Mild motor difficulties, repetitive non-rhythmic movements of the right upper and inferior limbs | Infarct of the thalamus | Imaging post-VZV CSF VZV DNA − VZV antibodies synthesis index + | ASA first, acyclovir + corticosteroid later | No neurological sequelae 1 y later focal stenosis MCA and 6 months later persistent mild stenosis |

| Buompadre et al., 2009 [34] | Argentine | Retrospective and prospective case series | 7 on 28 | 3 mo–6 y/3.6 y | 15 d–6 mo/3 mo (median) | TIA (transient hemiparesis, arm weak- ness, gait disturbance) hemichorea, seizures | (3) stenosis of MCA, (1) occlusion of MCA, (7) infarct of GB and internal capsule | Imaging post-VZV | Not specified individually for VZV cases | (1) severe hemiparesis and dystonia, (2) mild hemiparesis, (1) dystonia, (3) no deficit. Normal vascular studies (5/7) |

| Fragata et al., 2021 [35] | Portugal | Retrospective case series | 1 on 7 | 2 y | NR | Hemiparesis and somnolence | Occlusion of basilar artery, pons ischemia | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV CSF VZV DNA + | Thrombectomy | Fatal ischemia of the brainstem and cerebellum |

| Davico et al., 2018 [36] | Italy | Case series | 2 | 3 y | 4–6 mo/5 mo (median) | Hemichorea | Unilateral stenosis of ICA, MCA, ischemic lesions of BG | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV | ASA, corticosteroid, haloperidol | Clinical recovery, no recurrence of AIS |

| Hausler et al., 1998 [7] | Germany | Case series | 4 | 4–16 y/9 y | 6 w–4 y/1.8 y (median) | Transient impaired speech, vegetative symptoms, hemiparesis, aphasia, and disturbed consciousness | Unilateral focal stenosis MCA, bilateral occlusion of ICA, ischemic lesions of BG | Imaging post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA − VZV antibodies synthesis index + (3/4) VZV IgA serum (1/4) | Corticosteroid + LMWH + ASA (2/4)Acyclovir+ Corticosteroid + LMWH + ASA (1/4) | No deficit (2/4), cognitive impairment (2/4), hemiparesis (1/4) residual stenosis (2/4) No recurrence of AIS (3/4) |

| Moriuchi H et al., 2000 [37] | USA | Case report | 1 | 12 y | 9 months VZV reactivation | headache, weakness of left hemibody | Irregularity of MCA, edema of BG | Imaging post-VZV CSF VZV DNA + | NR | No neurologic deficit |

| Rougeot et al., 2006 [38] | France | Case report | 1 | 2 y | 1 mo | hemiplegia, somnolence, vomiting | Unilateral occlusion of MCA | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA − and IgG − | ASA | Expressive aphasia, moderate right upper limb weakness and neglect No recurrence of AIS |

| Kawatani et al., 2011 [39] | Japan | Case report | 1 | 6 y | 5 w | Hemiparesis, aphasia | Unilateral irregularity of MCA | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA − and IgG − antibodies synthesis index positive at follow-up | ASA | Mild dysfunction in fine-tuned movement of the right hand Stenosis of ACA e MCA, aneurism of ACA |

| Nguyên P. et al., 1994 [40] | France | Case series | 1 of 6 | 2 y | 3 w | Hemiparesis | Unilateral ischaemic zone of internal capsula | NR | NR | Evolution favorable |

| Driesen et al., 2015 [41] | Belgium | Case report | 3 | 1.5–3 y/2.2 y | 1.5–8 m/4.2 m (median) | Hemiparesis, speech disorder | Infarct of capsula interna, of BG and parietal region | Imaging post-VZV CSF VZV DNA + (2) | Acyclovir + corticosteroid + ASA (2) Acyclovir + Corticosteroid + LMWH followed by ASA | Complete recovery (3), no residual alteration at imaging (2) |

| Hayes B et al., 2007 [42] | Ireland | Case report | 3 | 5–7 y/6 y | 2 w–1 mo/0.8 mo (median) | Hemiparesis, gait abnormality, dystonia, hemi-facial dropping, dysarthria | Unilateral stenosis of MCA, occlusion of ICA, infarct of BG | Imaging post-VZV CSF VZV DNA and IgG + (1) | Acyclovir + corticosteroid + ASA (1) Acyclovir + corticosteroid | Epilepsy, moderate deficit of arm, mild of lower limb, progression of stenosis (1) no progression (2) No recurrence of AIS (2) |

| Sabry et al., 2014 [43] | USA | Case report | 1 | 6 y | 1 y after reactivation (only VZV vaccination) | Hemiparesis, paresthesias, dizziness, urinary incontinence | Multifocal stenosis of ACA, anterior communicating artery and bilateral stenosis of MCA, supraclinoid ICA | Imaging post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA + compatible with varicella vaccine strain | Acyclovir + corticosteroid + ASA | No neurologic residual |

| Bodensteiner JB et al., 1992 [44] | USA | Case series | 5 | 3–7 y/5.8 y | 3–8 w/5.4 w (median) | Hemiparesis, seizure, headache, lethargy | Unilateral focal stenosis of MCA (1/5) cortical stroke (4/5), deep stroke (2/5) | Imaging post-VZV | Corticosteroid + ASA (1) corticosteroid (1), dipyridamole (1) | No neurologic residual, no recurrence of AIS |

| Yilmaz K et al., 1998 [45] | Turkey | Case report | 1 | 18 mo | 10 d | Hemiplegia, gait disturbance, seizure | Infarction of BG and internal capsule | Imaging post-VZV | NR | Mild hemiparesis |

| Magagnini MC et al., 2015 [20] | Italy | Case report | 1 | 5 y | 1 mo | Hemiplegia, speech impairment | Infarction of BG | Imaging post-VZV | Acyclovir | No neurologic residual, no recurrence of AIS |

| Morino et al., 2009 [46] | Japan | Case report | 1 | 2 y | 9 d | Hemiparesis | Bilateral stenosis of MCA, ACA and ICA (supraclinoid) | Imaging post-VZV | ASA | Improvement of neurologic condition, no recurrence of AIS |

| Singhal AB et al., 2001 [47] | USA | Case report | 1 | 14 y | 4 mo | Hemiparesis, aphasia, diplopia, monocular blindness | Unilateral stenosis of MCA, ICA; infarct of BG | Imaging post-VZV CSF VZV IgG + | Acyclovir + Corticosteroid + ASA | No neurologic residual, resolution of stenosis, no recurrence of AIS |

| Danchaivijitr N et al., 2006 [48] | UK | Case report | 1 | 7 mo | 2 mo | Somnolence, apnea, bradycardia at onset, after hemiparesis and seizure | Unilateral focal stenosis of ACA, interhemispheric hematoma, subarachnoid and intraventricular hemorrhage, hydrocephalus | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA − and IgG − | NR | No neurologic residual, resolution of stenosis, no recurrence of AIS |

| Shaffer L et al., 2003 [49] | UK | Case series | 1 of 5 | 2 y | 2 mo | Transient weakness of hemibody | Unilateral focal stenosis of MCA, infarct of internal capsule | Imaging post-VZV | NR | No neurologic residual, no recurrence of AIS |

| Bulder MM et al.,2013 [50] | Netherlands | Case series | 3 | 2–3 y/2.7 y | 2–7 mo/4 mo (median) | Unilateral dystonic movement, hemicorea, gait disturbance | Unilateral stenosis of ICA, MCA, ACA, infarct of BG | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV CSF VZV DNA + (1) and − (1) | Acyclovir + ASA (1), ASA (2) | No neurologic residual (3) no change in stenosis (1), resolution of arteriopathy (1), no recurrence of AIS (3) |

| Ganesan V et al., 1997 [51] | UK | Case series | 7 | 8 m–6 y/4 y | 1 w–4 mo/1.57 mo (median) | Hemiparesis, visual impairment, signs of encephalopathy with cardiorespiratory compromise | Unilateral stenosis of MCA (3), occlusion of MCA (1) and PCA (1), 1 moyamoya | Imaging post-VZV | ASA, warfarin (1), ECMO (1) | No neurologic residual (1) dystonia (1) hemiparesis (1) persistent stenosis (1) no progression of stenosis (1) recanalization of occlusion (1) no recurrence of AIS (2) TIA (1) |

| Berger et al., 2000 [52] | Switzerland | Case report | 1 | 4 y | 13 mo | Hemiparesis, aphasia | Unilateral stenosis of ICA, occlusion of MCA | VZV antigen–positive giant-cell arteritis on autopsy | ASA | Fatal |

| Hattori H et al., 2000 [53] | Japan | Case report | 1 | 1.5 y | 3 mo | Hemiparesis | Unilateral focal stenosis MCA, infarct of BG | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV CSF VZV DNA − and IgG + | ASA | No neurological abnormalities, recurrence 5 months after |

| Aydin K et al., 2006 [54] | Turkey | Case report | 1 | 2.5 y | 3 w | Hemiplegia, gait disturbance, aphasia | Ischemic zone of BG | Imaging post-VZV | NR | Mild hemiparesis |

| Marques P et al., 2021 [14] | Portugal | Case report | 1 | 4 y | 4 mo | Nystagmus, dysmetria, ataxic gait, headache, vomiting | Focal stenosis basilar artery extending to antero-inferior cerebellar arteries bilaterally, right cerebellar infarct | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV CSF VZV DNA + | Acyclovir+ corticosteroid+ ASA | No neurologic residual, improved arteriopathy |

| Darteyre S et al., 2014 [55] | France | Case report | 1 | 10 y | 5 mo | Somnolence, headache, vomiting | Unilateral focal stenosis of supraclinoid ICA, occlusion of MCA | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV CSF VZV DNA + | ASA | No neurologic residual, improved occlusion, no recurrence of AIS |

| Bartolini L et al., 2011 [56] | Italy | Case series | 4 | 2.2 mo–5.1 y/3.8 y | 0.5–7 mo/2.9 mo (median) | Hemiparesis, hemichorea, aphasia | Unilateral stenosis of MCA, ACA and ICA (1), MCA (2) bilateral ACA, MCA (1), infarct of BG (1) | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV CSF VZV DNA + (1) | Acyclovir+ ASA+ LMWH (1), ASA (2), LMWH + ASA (1) | No neurologic residual (3) minimal hemiparesis (1), no recurrence of AIS |

| Daugherty W.P. et al.,2009 [57] | USA | Case report | 1 | 14 y | NR | Headache, decreased sensation of right face, arm and hemithorax | Fusiform aneurysms of basilar artery extending to PCA, unilateral aneurysms of ICA, unilateral infarct of thalamus | Imaging post VZV CSF VZV DNA + | Acyclovir+ ASA | Stability of aneurysm, no recurrence of AIS |

| Beleza P. et al., 2007 [5] | Portugal | Case report | 1 | 3 y | 5 mo | Hemiparesis | Unilateral focal stenosis MCA | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV CSF VZV DNA - | Acyclovir+ ASA+ LMWH | Resolution of stenosis, no recurrence of AIS |

| Losurdo G. et al., 2006 [58] | Italy | Case series | 4 | 0.5–6 y/4.1 y | 2 d–1 mo/12.7 d | Hemiparesis, meningeal syndrome | Unilateral focal stenosis MCA, occlusion of MCA, infarction in the territory of MCA and of BG | Imaging post-VZV | Acyclovir + ASA (4) and LMWH (1) or Rt-PA (1) | Clinical improvement (2), not completely recovered (2) recurrence of hemiparesis and seizures (1) no recurrence (1) |

| Sébire G. et al., 1999 [59] | France | Case-control study | 7 of 11 | 1 mo–15 y | 9 d–9 mo/6 w | NR | NR | Imaging post-VZV | NR | Regression of arteriopathy (9) stabilization (2) [not specified for VZV group] |

| Nagel MA et al., 2008 [12] | Multi-national | Case series | 7 of 30 | 1–18 y/5.4 y | 6 d–20 mo/5.3 mo | NR | Focal vascular lesion: (5) mixed (2) small vessel | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA + (2) and IgG + (5) | Acyclovir + corticosteroid (3) Acyclovir (2) | Clinical improvement (5), stabilization (1), slow improvement (1) |

| Our case report | Italy | Case report | 1 | 1 y | 5 mo | Hemiparesis | Unilateral focal stenosis of MCA | Focal cerebral arteriopathy post-VZV, CSF VZV DNA + | Acyclovir + Corticosteroid + ASA | No neurologic residual, no recurrence of AIS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Testaì, M.; Marino, S.; Russo, G.; La Spina, M. Post-Varicella Arteriopathy as a Cause of Pediatric Arterial Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Case Report. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121333

Testaì M, Marino S, Russo G, La Spina M. Post-Varicella Arteriopathy as a Cause of Pediatric Arterial Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Case Report. Brain Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121333

Chicago/Turabian StyleTestaì, Martina, Silvia Marino, Giovanna Russo, and Milena La Spina. 2025. "Post-Varicella Arteriopathy as a Cause of Pediatric Arterial Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Case Report" Brain Sciences 15, no. 12: 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121333

APA StyleTestaì, M., Marino, S., Russo, G., & La Spina, M. (2025). Post-Varicella Arteriopathy as a Cause of Pediatric Arterial Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Case Report. Brain Sciences, 15(12), 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci15121333